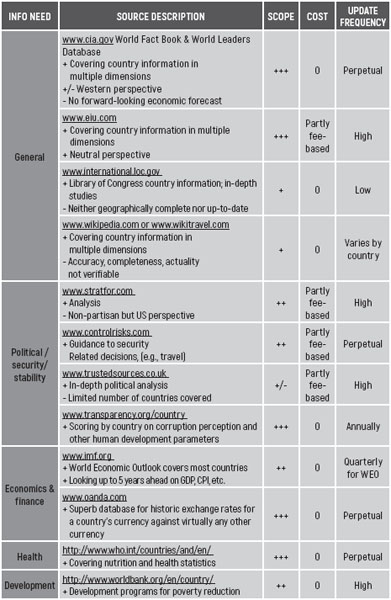

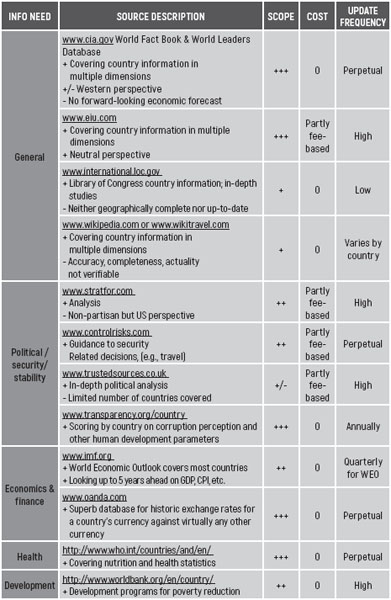

TABLE A2.1 SOURCES PROVIDING COUNTRY DATA (ECONOMICS, POLITICS, CULTURAL)

APPENDIX 1: CONVERSATION TECHNIQUES IN DATA COLLECTION

Elicitors use conversational techniques methods to avoid asking overtly probing questions and still draw information from their target. The list of techniques below, adapted from an FBI brochure, is not necessarily exhaustive (FBI, 2014). Each of the techniques mentioned is referred to by its specific trigger. An example of a statement is provided for each trigger. A superficial analysis is made of what human psychological or social norm-induced behaviour this trigger appeals to. For some triggers the risks of use are included. It has been stated before in this book: this is practitioners’ guide, not a scientific study. The author does not pretend to have an in-depth understanding of psychology. The aim is to illustrate, and most of all to warn, but certainly not to explain.

| TRIGGER 1 | MAKE SUGGESTIVE STATEMENT |

Example:

“I bet you got over 100 new customers because of this innovation.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s (human) tendency to correct others.

• Subtly addresses recognition need through mild flattery.

The FBI brochure suggests using leading questions with a similar purpose (FBI, 2014). Using questions in in general – particularly leading questions – is to be avoided at all times.

| TRIGGER 2 | BRACKETING |

Example:

“Sales because of this innovation must be between € 5 – 15 Million?”

Appeals to:

• Target’s (human) tendency to correct others.

| TRIGGER 3 | ‘REPEAT – A – WORD’ |

Example:

Target: “We have lots of new customers due to the innovation.”

Elicitor: “Lots?” [accompanied by smart body language & intonation]

Appeals to:

• Target’s (human) tendency to correct others.

• Target’s need to get recognition.

Risk:

Target may get suspicious when using ‘Repeat-a-Word’ more than once

| TRIGGER 4 | BE A GOOD LISTENER AS A TARGET COMPLAINS |

Example:

Target: “There is no f***ing way I pick up wireless here to let me check the web.”

Elicitor: “I am sorry; do you want to use my 3G on my iPad?”

Appeals to:

• Target’s showing strong dislike of something.

• Target’s openness during trying circumstances.

• Target’s response to kindness, which really helped.

| TRIGGER 5 | INCORRECT STATEMENT |

Example:

Elicitor: “I saw two press releases on FrieslandCampina acquisitions.”

Target: “What do you mean two? There is only one – the other one is not in the public domain as far as I know.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s (human) tendency to correct others, especially when pride in someone’s job or capabilities is at stake.

• Target’s inability to control emotion: outburst led to indiscretion.

Risk:

This can be a show-stopper if the target realizes he’s been triggered; it can put him on High Alert and result in severe distrust. And trust in the elicitor is gone for good.

| TRIGGER 6 | QUOTE REPORTED FACTS |

Example:

Elicitor: “I saw double-digit value sales growth in your cheese business in the last quarter.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s tendency to recognition for his achievements.

Risk:

When feeding the target real facts in ‘quid pro quo’ way, the elicitor always will ensure that the result of the conversation is that he gained more than that he gave.

| TRIGGER 7 | GOSSIP/CONFIDENTIAL BAIT |

Example (in conspiracy tone, bit hush-hush):

Elicitor: “Off the record, of course, but I trust you also looked at buying WBD?”

Target: “Sure we did, but we just couldn’t justify paying what PepsiCo did.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s valuing themselves above others.

• Target’s need for recognition.

• Target’s implicit moral obligation to return the favor given (reciprocity): the elictor gives a secret, now the target gives a secret. This is the bizarre, competitive dynamic of ‘who’ dares to release the biggest secret?’

| TRIGGER 8 | PROVOCATIVE STATEMENT |

Example:

Elicitor: “Margins in processed cheese will never exceed 10% ROS.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s tendency to correct; this is a strongly developed trait in teachers, professors, experts.

• Target’s tendency to show off understanding (recognition).

In the FBI brochure this trigger is referred to as ‘criticism’ (FBI, 2014). The goal is to make the target upset with his employer, for example, prompting him to release non-public information about the employer. The risk with overly harsh criticism is that the target may simply get annoyed and walk away, or get angry and alarmed that he is a victim of elicitation. Using criticism without directly connected-praise is to be avoided.

| TRIGGER 9 | FEIGNED OR REAL DISBELIEF |

Example:

“Did you really invest €100 Million in that expansion? Wow.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s tendency to value recognition for achievement.

Risks:

The risk of feigning disbelief (or recognition, for that matter) is that the target may see through the elicitor’s set-up. The target may get suspicious or plainly recognizes the hypocrisy and dislike her for it. This means the source is ‘wasted’ on this particular occasion.

A second risk is that the elicitor may themselves start to mentally reject their own behaviour, as the hypocrisy required for satisfying some business info need may increasingly conflict with the elicitor’s personal values. Such self-denial of values may be reasoned away by an elicitor when needed to win a war, as the cause justifies the means. But abandon one’s principles for a commercial assignment from a business services agency, on behalf of some anonymous corporate client? Such commendable values may make the elicitor functionally less effective.

| TRIGGER 10 | START A SENTENCE |

Example:

“It is hard to recruit good staff in.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s tendency to complete / correct others.

| TRIGGER 11 | FLATTERY (DISGUISED AS CRITICISM) |

Example:

“We initially didn’t consider your acquisition in China a smart move.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s need for recognition for achievement.

• Target’s tendency to correct others.

Risk:

This can be a risky move, as it might offend and anger the target, and end up shutting him down entirely.

| TRIGGER 12 | NAIVE STATEMENT |

Example:

“We really didn’t understand how you could offer this product so cheaply.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s need for recognition (of achievement).

• Target’s tendency to correct others.

Risk:

This is also a dangerous weapon because it may hurt the elicitor’s credibility (especially if he’s a peer and dissuade the target from talking further, as she may view the elicitor as simply too clueless to waste her time on).

| TRIGGER 13 | REASSURANCE |

Example:

“We operate in different markets anyway.”

Or

“When we talked to your CFO last month, he shared…[feeding sensitive info].”

Or

“Neither you or I work for ABC Ltd., and neither of us understands their business model.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s need for safety.

• Target’s inability to value the information properly.

• Target’s need for social validation; it is no problem when superiors do the same.

• Target’s tendency to complete/correct others.

• Target’s tendency to show off understanding (for recognition and praise).

| TRIGGER 14 | PROVIDE BREAKING NEWS |

Example:

“I see here on my iPhone that the CEO of company ABC just resigned.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s curiosity, news hunger.

| TRIGGER 15 | OFFER ETHICAL DILEMMA |

Example (knowing that the competitor is operating a business in West Africa):

“A friend of mine who’s a business development director in another industry sector [imaginary of course] recently considered investing in West Africa, as that market shows strong growth prospects, but he just had no clue how to handle the corruption.” [Then either silence, or a question like: ‘What do you think?’]

Appeals to:

• Target’s tendency to complete/correct others.

• Target’s tendency to show off understanding (recognition).

Risk:

This is potentially a powerful technique, as it will reveal a great deal of the other party’s real intent. There are few better indicators of intent than how a real-life dilemma was handled. The target, however, may see through the objective of the elicitor, and immediately lose trust.

| TRIGGER 16 | VOLUNTEER INFORMATION |

Example:

“We reported 1% sales growth, when consolidated in €, due to currency headwinds in the last quarter of 2013 in our emerging markets businesses.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s tendency to complete/correct others.

• Target’s implicit moral obligation to return the favor given (reciprocity) – the elicitor gives a secret, now the target gives a secret. Once again, this is an example of the strange, competitive dynamic of who’s willing to release the biggest secret.

Risk:

When pumping the target with real facts as a quid pro quo tactic, the elicitor will always see to it that they gained more than than they give. Moreover, the elicitor ensures that they only give public domain information.

| TRIGGER 17 | CAN YOU TOP THIS? |

Example:

“We heard the volume growth of Company D’s yoghurt sales in Germany was over 30% last year. Just imagine trying to manage that sort of growth.”

Appeals to:

• Target’s tendency to show off understanding (for recognition and praise).

| TRIGGER 18 | ‘DISCOVER’ MUTUAL INTEREST |

Example:

“You also attend this conference often right? Suppose you visited last year as well when it was held in Ireland. So much hot air we heard on the Irish dairy industry remember?”

Appeals to:

• Target’s tendency to belong to a group.

• Target’s tendency to complete/correct others.

| TRIGGER 19 | SILENCE |

Example:

“So that puts me in a tough position…” (accompanied by the elicitor pretending to thoughtfully dwell on his dilemma, with corresponding body language) .

Appeals to:

• Target’s tendency to keep talking: silence is uncomfortable.

Risk:

This poses risks because breaking the conversational flow might prompt the target to lose interest and walk away.

An elicitor will not use every trigger in every conversation. This is an iterative, on-the-fly process they: test which triggers work to keep the conversation going, whilst ensuring the conversation is focused on capturing the data the elicitor is after.

APPENDIX 2: SOURCES SEGMENTED BY DATA NEEDS

TABLE A2.1 SOURCES PROVIDING COUNTRY DATA (ECONOMICS, POLITICS, CULTURAL)

All industrialized nations and most developing/emerging countries publish extensive statistics online. For example, for the Netherlands visit www.cbs.nl for general statistics and www.dnb.nl (The Dutch central bank) for monetary statistics, interest rates, etc. For developed and some developing countries, check either www.tradingeconomics.com or www.oecd.org . For the European Union, consider using Eurostat: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/statistics/themes

Country studies are often carried out by think tanks. Visit the site of Penn State University to find an appropriate entity http://gotothinktank.com/2015-global-go-to-think-tank-index-report/

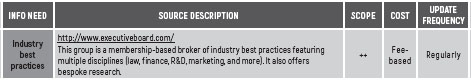

TABLE A2.5 SOURCE PROVIDING INDUSTRY BEST PRACTICES

APPENDIX 3: INTERNET SEARCH OPERATORS

Next to the common operators AND and OR, the operators covered below are offered by most internet search engines to narrow down the number of search results and increase the relevancy of the search results that are being obtained:

• Adjacency

• Around

• Filetype:

• Intitle:

• Inurl:

• NOT

• Range

• Site

• Truncs

This is but a small sub-set, selected on the basis of their likely usefulness to a business strategy analyst. Search specialists are encouraged to check other sources for more details, for example the 2007 NSA manual (NSA, 2007).

ADJACENCY

The adjacency operator allows searching for terms in a fixed subsequent order. For the sake of simplicity, the Google formatting for the adjacency operator is used.

It is outside the scope of this work to cover the multitude of available search engine formats. The reader who wants to use other search engines will easily retrieve the specific formats that are actual at the time of searching. Search engines are run by commercial companies that may have commercial reasons to change their formats. Unfortunately and in contrast to scientific disciplines like physics or chemistry there are no global standards. In chemistry the element lead is abbreviated by Pb; that abbreviation is universally recognized in any chemistry lab anywhere in the world. On Google, AND is represented by a space, on Bing it’s denoted by the word AND, and Yahoo uses ‘+’.

In the intermezzo at the bottom of chapter 6 the example of processed cheese is given. The search query “processed cheese” in Google Boolean language means processed AND cheese, as the space is defined as logical AND. Starting and ending the query with quotation marks (“processed cheese”) will only give results where the words processed cheese are featured immediately next to each other.

Apart from its use in successive fractions, the adjacency operator is also highly useful to retrieve the source of a particular document. When a hard copy, even a single page, of a document without a source, reaches the analyst, she should try to locate the full document. This is simple housekeeping. The analyst needs at least to establish the publication date, the author and preferably some sourcing context. The adjacency operator is a great help. Statistically the chances of, say, seven words appearing in exactly the same sequence in multiple documents is really small, unless these words form a definition that is commonly used across multiple documents.

The following example will illustrates this. When a one-page hard copy document without a source appears

on an analyst’s desk with in it the sentence:

“Pertinent information is highlighted and not obscured by a mass of trivial facts.”

Chances are slight that the search query “pertinent information is highlighted and not obscured” will result in many hits. Running that query (www.google.nl, 21 December 2013) yielded only two hits, of which the first indeed gives the full report in which the sentence appears (Canadian Land Forces, 2001d). The adjacency operator thus offers an extraordinary efficient process to locate data on the web.

The drawback of using the adjacency operator is that the sequence of the terms must be exact. A query aimed at data on “whey derivatives” will not find a report on “whey protein derivatives”. In Google, the adjacency search operator has a solution for this.

The search query “whey * derivatives” will retrieve results where a maximum of one word is located between whey and derivatives. “whey * * derivatives” allows for two words in between the two search terms etc.

AROUND (PROXIMITY)

The proximity operator – in Google featured as the AROUND(x) format – enables to search for different terms simultaneously in no particular order, but they must be close to each other. The x variable in between the quotation marks indicates the number of words that are allowed to appear between the two search terms.

The search query whey AROUND(2) derivatives will for example retrieve documents with the text:

• …derivatives of the whey…

• …whey protein derivatives…

It will not retrieve a reference to a whey from casein is the source for multiple derivatives .

The AROUND operator is much more specific than the AND operator, as it allows retrieval of only those documents where the search terms are close to each other.

FILETYPE:

In Google, the filetype: operator restricts the search results to a chosen filetype. A common search approach to find original reports on a particular topic rather than news items that stem from those reports is to specify as filetype:pdf.

In the example of the intermezzo that closes out chapter 6 on processed cheese, you saw that the adjacency query “processed cheese” resulted in 1,380,000 hits (at www.google.nl, 21 December 2013). Changing the search query into filetype:pdf “processed cheese” resulted in 41,800 hits. Restricting the output to pdf-files thus only results in a narrowing of the results to about 3% of the original search output.

INTITLE:

In Google, the intitle: operator searches only for words in the title of a document. Building further on the processed cheese example from the intermezzo in chapter 6 , the mix of an adjacency query and intitle: has as (Google-)syntax intitle:”processed cheese”. This query yields 17,400 hits. It is critical to not put a space between the double colon and the first bracket of the search string. Using a combination of the intitle: and adjacency operator leads to a narrowing of the results output to about 1% of the number of hits where the intitle: condition had not been specified. The resulting set probably has higher relevancy.

Combining filetype: and intitle: further narrows the results. The (Google-)syntax looks: inurl:”processed cheese” filetype:pdf. This query results in only 489 hits. Adding Netherlands to the search query results in only fifteen hits.

The first two hits provide (fee-based) reports on the processed cheese market in the Netherlands. These reports feature the processed cheese producers I’d looked for as well.

INURL:

In Google, the inurl: operator searches only for words in the url of a document. For processed cheese the query inurl:”processed cheese” yields 50,800 hits (at www.google.nl, 21 December 2013).

The inurl: operator is particularly useful to select domain name groups. The syntax for Netherlands focused query can be: inurl:.nl. Similarly, work from educational institutions can thus be retrieved by using inurl:.edu etc.

In Google, the Boolean NOT operator has a –symbol as syntax. To search for processed cheese that does not originate from France, the syntax reads: “Processed cheese” –France.

This results in 1,240,000 hits, compared to 1,380,000 hits without the limiting condition of excluding France.

The syntax “Processed cheese” -.com only yields results from web sites that do not have a .com domain. This yields 207,000 hits – only 15% of the “processed cheese” hits originate from a non .com domain.

RANGE

The range operator allows one to select a quantitative range. The syntax is a … This means that a search query wine 1980…1985 gives results on wines produced in that period. This operator may be useful to locate an older annual report of an company, but for that information this approach is generally a last resort, used when all annual report databases have been exhaustively and unproductively searched.

SITE

In Google, the site operator allows selection from websites from a particular domain. The syntax is site.

For processed cheese sites that only originate from Belgium, a search query reads site:.be “Processed cheese”. This query yields 3790 results; the same query for .nl yields only 1140 results. The site operator is thus a powerful tool in narrowing down results. The question remains whether the country-specific domain names are still used often enough to generate enough relevant results on a query.

TRUNCS

The Trunc operator is useful when the root of a search term is clear but not the whole term. A search on chees? retrieves both cheese and cheesecake.

This operator is also useful when results, both with singular and plural forms, are sought after: for example cheesecake? which retrieves both cheesecake and cheesecakes.

In contrast to (partly fee-based) services like Lexis-Nexis and Factiva, Google searching does not, at the time of me writing this Appendix (December 2013) support Trunc searching.