italian

gardens

My taxi driver in Rome was sure it was a mistake and sent me back into the hotel to have someone translate the note I had handed him. It was six o’clock in the morning, and my note said, in Italian, “Please take me to the Rome produce market.” Once there, I understood immediately why the driver thought I had made a mistake. The place was alive with people, occasional verbal abuse was being exchanged, purveyors pushed dollies and jockeyed for position, and utter chaos reigned. I was a little on edge, but after one glimpse at the stacks of spectacular and unfamiliar vegetables everywhere in sight, I relaxed. I had dedicated more than ten years to edible plants, and it was exciting to see some I didn’t know. And now I’d find out why vegetables and fruits I’d been eating in restaurants throughout Italy had been so outstanding.

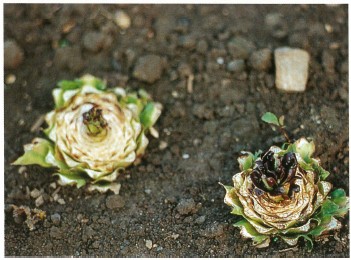

Baby artichokes, romanesco type broccolis, and ruby heads of radicchios (left) are domesticated versions of plants that have been used in Italy since ancient times. Another such plant, the Judas tree or European red bud (Cercis siliquastrum), shown here, blooms in spring, and the magenta blossoms are enjoyed raw in Italy in salads or pickled in vinegar.

I was intimidated at first by all the shouting, but within minutes the passion both vendors and buyers showed for the produce put me at ease. Besides, how can a food lover be cool in front of a waist-high pile of purple artichokes? The men beamed at my continued delight as I wandered through the stalls and exclaimed over sculptured chartreuse broccoli, purple cauliflower, and stalks of miniature fava bean plants covered with pink flowers. “Do you eat the leaves and the flowers?” I tried to ask, eliciting shrugs and loud laughter. I wondered about the contorted stems of what looked like celery (the chicory ‘Catalogna Puntarella,’ I found out later) and marveled over bright magenta spheres. “Radicchio!” the vendor cried. We all exchanged fabulous gestures as I tried to put English words to vegetables and varieties I’d never seen before.

Prior to my first trip to Italy almost fifteen years ago, Italian vegetables had meant mostly zucchini and tomatoes to me. The herbs were garlic and basil, and Italian cuisine was primarily pizza and spaghetti. Now I know that while these items are Italian, they make up only a small part of the cuisine—mostly from southern Italy. I learned about marinated vegetables—bright red peppers and sweet onions with fennel, all bathed in olive oil and herbs. I came to love deep-fried cardoon (a close relative of the artichoke) and to savor slices of sweet cantaloupe wrapped with prosciutto, as well as bagna cauda, a vast range of raw vegetables dipped in cream and olive oil flavored with anchovies and garlic. I consumed loads of pesto and memorable salads made with endive, tangy arugula, and radicchio. And the pasta! I sampled sauces far more imaginative than our nearly mandatory tomato sauce. In Italy pasta is made in a wide variety of shapes and might be served with a cream sauce and crowned with fresh baby peas or string beans. What revelations! What bliss!

I returned from Italy filled with enthusiasm and, already missing the food, determined to track down the vegetables and herbs I had seen and to learn how to cook them. I visited Italian markets, perused specialty seed catalogs, and interviewed Italian gardeners. The latter two sources yielded the most information. A love of gardening is part of the Italian heritage, which, together with frustration at the limited selection and quality of supermarket vegetables, had inspired many of the Italian Americans I met to plant extensive gardens filled with unusual vegetables. Many of the owners of the specialty seed companies similarly started their businesses out of a frustration with the limited availability of varieties of European seeds in the United States. They had discovered the Italian vegetables and were as excited about them as I was.

No wonder Americans, using supermarket produce that often tastes like the cardboard it’s packaged in, simply can’t duplicate the “taste of Italy.” Americans might have recently discovered balsamic vinegar and fresh mozzarella, and some American gourmets are spending eight dollars a pound on radicchio, but many Italian specialties such as cardoon, the spicy rustic arugula, leaf chicories, broccoli raab, purple artichokes that can be eaten raw, the melting yellow romano beans, and the mellow mint nepitella are still not available. It looks as though anyone who wants to experience the rich spectrum of tastes of true Italian cooking is still going to have to plant a garden!

A woman strings cherry tomatoes (left) in preparation for drying. Drying is the most common use for cherry tomatoes in Italy, and it is most associated with the hot, arid, areas in the south.

Like in much of Europe, small farmers’ markets (right) are very popular in Italy. The number and quality of similar markets in the United States is growing quickly, and they are great places for gardeners to learn more about vegetable varieties that grow well in their climates.

how to grow an italian garden

The majority of vegetables and herbs planted in an Italian vegetable garden, and the methods for growing them, are very similar to the crops and methods used in most gardens. In Italy small plots of ground are cultivated near the home, and individual vegetables are most often grown in rows. Many of the vegetables are comfortably familiar to us, namely, tomatoes, beans, zucchini, cucumbers, eggplant, broccoli, lettuce, and peppers. In fact, sometimes they grow the identical variety.

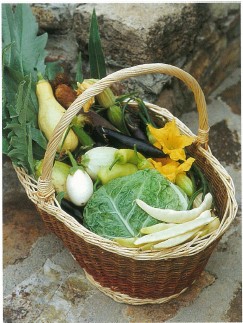

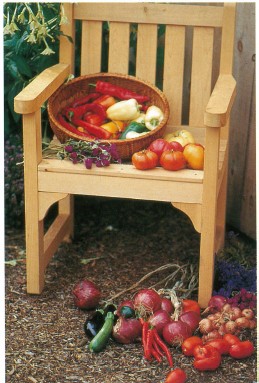

But as a rule, Italians grow slightly different varieties of our favorite vegetables. The Italian tomato varieties are most often paste types, the sweet peppers are frequently long and thin rather than short and blocky, the green beans are often flat romano types or curved anellinos, and the eggplants are generally smaller and either elongated or round. In addition, in Italy gardeners grow a number of vegetables and herbs that are less common here: including Tuscan black kale (lacinato); many kinds of cutting and heading chicories; borlotto-type, pink-striped shelling beans; large flat and purple artichokes; ‘Tromboncino,’ elongated squashes; sweet fennel; all sorts of greens; and many varieties of large-and small-leafed basils. (And while not easily grown, another Italian favorite, capers, can be grown here in mild climates.) In addition, Italians harvest many plants from the wild and grow some of them in their gardens. Italian gardeners grow and harvest “baby greens” and garden blanch (deprive the plants of light to make them more tender and less bitter) many of the chicories, endive, and cardoon.

This harvest (right) includes Italian parsley; basil; paste and the fluted, flat ‘Costoluto Genovese’ tomatoes; ‘Milano’ zucchini; ‘Violetta Lunga’ eggplant; and ‘Rossa di Milano’ and ‘Giallo di Milano’ onions. It was harvested at The Cook’s Garden trial plots in Burlington, Vermont. Like a number of American seed companies, Cooks is increasingly interested in Italian varieties because of their great taste.

To enjoy many of the Italian specialties in your own garden, you must order both the Italian varieties of common vegetables and the more unusual vegetables and herbs from specialty seed companies. See Resources (page 102) for the names and addresses of mail-order seed companies and nurseries.

Because Italy is on the Mediterranean, its climate is characterized by long, hot summers with very little rain, fairly mild winters, and a long spring and fall. The long growing season allows the Italian gardener to plant slow-maturing plants, such as some of the radicchios, many garlic varieties, and some varieties of sweet peppers; to plant vegetables that grow best in a long, cool spring, such as fava beans and cardoon; to enjoy the tender perennial artichoke; and to sun-dry tomatoes with ease. In the United States a similar climate is found in parts of California, Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. American gardeners in other states who want to grow these plants sometimes must make cultural compromises. Gardeners in the humid South need to plant especially disease-resistant varieties and will have the most success if they provide afternoon shade for species that suffer in the heat. Gardeners at high altitudes and in cool northern areas will do beautifully with some of the spring and fall vegetables but need to provide extra heat for tomatoes, peppers, melons, and eggplant. Here black plastic mulches, windbreaks, south-facing masonry walls, and floating row covers help raise the ambient temperature by 5 to l0°F.

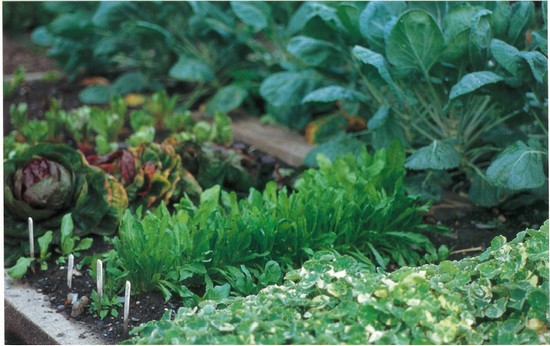

My front yard spring vegetable garden (left) a few years back included many vegetables and herbs enjoyed in Italy. The beds were filled with tall, purple sprouting broccolis, beets, chard, arugula, chicories, and lettuces as well as rosemary, oregano, fennel, thyme, and parsley.

I find that to fully appreciate any garden or cooking situation enough to write about it, I need to grow and cook with most of the featured plants. To this end, I have enthusiastically grown and cooked with hundreds of Italian vegetables and herbs and visited many sumptuous gardens. I offer you my own experiences with these wonderful varieties in the pages that follow.

italian specialties

Picking and Growing Wild Greens

It is difficult to delve into Italian cooking without coming across references to foraging and serving wild greens and herbs. Generations of Italians have stayed close to the land, often under very lean conditions. For their survival, and because many outlying towns remained isolated, rural Italians continued to harvest from the wild after much of Europe had ceased doing so. For many years this practice had little status, and the plants gathered, like borage and mustard, were considered peasant food. Nowadays upscale restaurants serve many of these “wild” greens, and it’s not unusual to find market stalls in Italy offering them too. Some of the greens are still gathered from the wild, but more often they are grown in market gardens. Italian cookbooks also call for wild greens these days, and proponents all over the world see consuming these nutrition-packed greens—whether grown domestically or in the wild—as a part of a healthy lifestyle. Even though some of these greens are not widely available outside of Italy, as a gardener you are in the fortunate position of being able to grow most of them yourself. Further, gardeners are better able to gather plants from the wild because they have the skills to recognize different species more readily than does a nongardener.

These plants may be uncommon in markets, but it’s not because they are hard to grow. After all, they grow untended in many parts of the world. In fact, give some of them a chance and they can become thugs and crowd out their weaker domestic cousins. As a gardener, you probably already know a few “up close and personal,” namely, dandelions and purslane (one of the pigweeds).

Over the years there have been dozens of plants associated with wild harvesting, some used as potherbs or vegetables, others used raw in salads.

In Italian these plants are referred to as erbe selvatiche. The more familiar ones include arugula (Eruca vesicaria, Diplotaxis tenuifolia); borage (Borago officinalis); burnet (Sanguisorba minor); the many chicories (Cichorium sp.); the cresses (Barbarea verna, Nasturtium officinale); dandelion (Taraxacum offiicinale); fennel (Foeniculum vulgare); corn salad, also called mâche and lamb’s lettuce (Valerianella locusta); hops (Humulus lupulus); mustard (Brassica nigra); nasturtiums (Tropaeolum majus); purslane (Portulaca oleracea var. sativa); salsify (Tragopogon porrifolius); sorrel (Rumex acetosa); and violets (Viola odorata). The more esoteric ones include chickweed (Stellaria media); Good-King-Henry (Chenopodium bonus-henricus); nepitella, also called calamint (Calamintha nepeta); minutina, also called erba stella and buck’s horn plantain (Plantago coronopus); shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris); silene (Silene vulgaris); mallow (Malva sp.); alexanders or black lovage (Smyrnium olusatrum); rampion (Campanula rapunculus); samphire (Crithmum maritimum); and nettles (urtica dioica), which must be cooked so the multitudinous prickly hairs on the leaves are softened.

A home garden in Italy (right) backs up to the Alps. In this cooler climate, summer gardens include broccoli, lettuces, leeks, onions, cabbages, and fava beans.

Historically, these wild greens were a welcome sight in the spring after a long winter of meals that were devoid of fresh edible leaves. The greens were consumed as a “tonic” to cleanse the system but were also enjoyed as a treat to the palate and for the senses after a gray winter. In fact, Italians who move to the city or away from Italy speak fondly of them. Italian chef Celestino Drago, who operates three restaurants in Los Angeles with three of his brothers, makes an annual pilgrimage to his home in Sicily. If he and his brothers cannot make the trip in early spring, their mom makes sure that they still enjoy the taste of the first flush of young wild greens, which she lovingly cooks or steams, drains, and freezes until her sons come home to her table. In the spring, when the California hills are covered with wild mustard, Drago gathers this potherb and continues the culinary tradition by preparing it for his family in several ways: as a simple vegetable, sautéed with garlic and olive oil; combined with a tomato sauce and spooned over pasta; or in risotto.

Seeds for many of the species mentioned above are available from specialty nurseries, but seeds for those plants known only as garden weeds (like shepherd’s purse and chickweed) may take a little more effort.

So let’s start with the easiest way to obtain these greens—seeing which ones are already growing wild in the fields and woods or growing as weeds in your garden. Obviously, these plants need to be identified properly. Use a field guide, such as the Peterson Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants; better yet, go out in the wild with someone who knows the plants (just as with mushrooms, a number of wild plants are poisonous). Keep in mind that common names are different all over the world, so use only the Latin names. Personally, I find Roger Phillips’s Wild Food a great help in identifying plants; it has many photos. Another helpful resource is the venerable Complete Book of Fruits and Vegetables, by a number of Italian botanists.

If you are gathering your greens from the wild, make sure they’re not growing by a heavily traveled road (to prevent lead contamination) and avoid rights-of-way that may have been sprayed with herbicides. The best time to forage is in the spring because all these greens need to be harvested when they are young or, if they are perennial plants, when they are producing new shoots and leaves. Very young plants or shoots are tender enough to be used raw in salads, but completely mature leaves are tough and bitter or acrid. Between the newest young shoots and the tough mature leaves is an in-between stage when the leaves are great cooked and used in soups or sauces; as fillings for a frittata, calzone, or torta; and as a topping on pizzas. They can also be blanched and made into nests that can be filled with cheese or eggs.

Cut-and-Come-Again Misticanza

The most common way to enjoy wild greens is in a misticanza, the Italian term for a combination of a variety of young, tender, and sweet leaves. Its French counterpart is called mesclun. However, in today’s restaurant vernacular, either mixture may in fact be just a mixed green salad containing many different lettuces and edible flowers—a far cry from freshly harvested young leaves in a combination of tastes and textures. According to Anna Del Conte in Gastronomy of Italy, “Roman gastronomes think a classic misticanza should include 21 different types of wild greens.... These include: arugula, sorrel, mint, radichella—a kind of dandelion—lamb’s lettuce, purslane, and other local edible weeds.” Some of us think that’s a bit extreme and settle for half a dozen or so.

The techniques for growing both an Italian misticanza and a French mesclun are identical. As few of us have all sorts of wild greens growing near our home, fortunately, there are prepackaged combinations of seeds for a traditional Italian misticanza available from specialty seed companies. For instance, the Cook’s Garden offers a Piedmontese mix with five types of chicories and four lettuces. Or you can mix your own combination of plants in which different tastes—for example, spicy, nutty, sweet, mild, and bitter—or different textures play off one another. As a note: Most of the seeds for the greens available from specialty growers are semi-domesticated; therefore, the plants will be more tender and succulent compared with foraged plants such as wild dandelion or chicory.

“Wild greens” (right, top, clockwise from top left) are borage, violets, sorrel, nepitella, purslane, nasturtiums, corn salad (mâche), and wild lettuce; rows of young nasturtiums and chicories (right, bottom) are ready for harvest as “wild greens.”

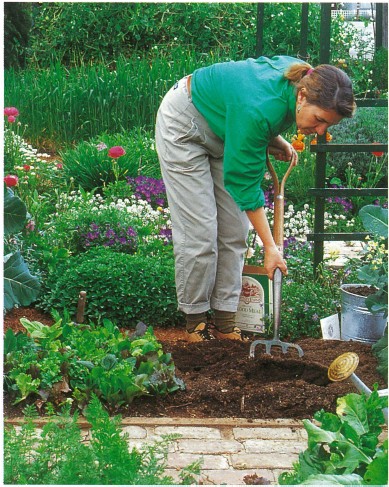

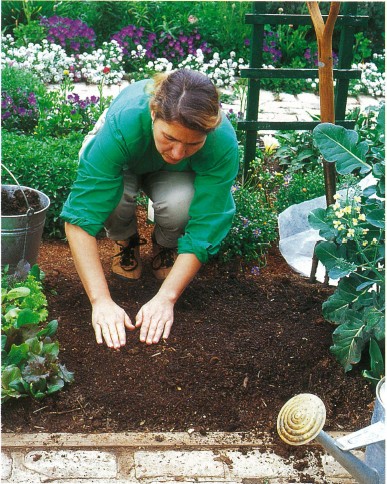

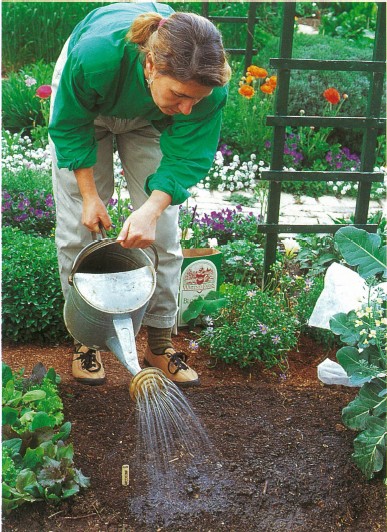

Gudi Riter steps away from her recipe testing to plant a small bed of baby salad greens, often called misticanza or mesclun, in my front garden. First (left, top left) the soil is prepared by applying four inches of compost, and a few cups of blood and bone meal, and working them into the soil with a spading fork. Once the soil is light and fluffy and the nutrients are incorporated, the seeds from a prepackaged mesclun mix are sprinkled lightly over the soil so that the seeds average ½ inch apart. A half inch or so of light soil or compost is then sprinkled over the bed and (left, top right) the seeds and the compost are patted down to assure that the seeds are in contact with the soil. A label that includes the name of the seed mix and the date is pushed into the soil (left, bottom left). The seeds are than gently watered in with a watering can until the soil is thoroughly moist. A piece of floating row cover (bottom right) is then applied to prevent critters from destroying the bed. To make sure the row cover won’t blow away, and critters can’t get in under it, the row cover is secured tightly by putting bricks or such at the corners, and along the edges if bird problems are severe.

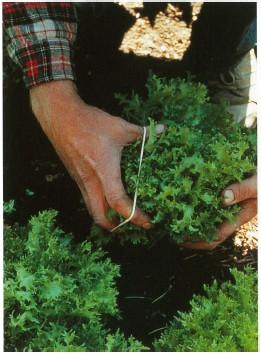

Growing a misticanza garden is easy and quick and is a rewarding way to start growing your own salad greens. Unlike large lettuces grown in rows in a traditional vegetable garden, you sow misticanza greens in a small patch and harvest them when the plants are very young (or if they are perennials, using only the newest shoots and leaves). One thing to keep in mind when choosing plants for your misticanza plot is to plant perennials in a separate location, for they will quickly outgrow the baby greens bed. Harvest your greens by plucking their young leaves as they are produced. An easy mix of plants for misticanza that is easy to start and maintain with the “cut-and-come-again” method of harvesting would consist of several baby lettuces of your choice, such as looseleaf ‘Lollo Rossa’ and the tender, small-leafed ‘Biondo Liscio,’ minutina; and two of the cutting chicories, ‘Ceriolo’ and ‘Catalogna Frastagliata.’ Another tasty blend is cress, arugula, the Catalonian cutting chicories ‘Dentarella’ and ‘Spadona,’ and several sweet baby lettuces such as baby romaine and salad bowl.

A misticanza bed can be grown in the spring or early fall. Choose a well-drained site that receives at least six hours of midday sun. Mark out an area about 10 feet by 4 feet—a generous space for a small family. Dig the area well and cover the bed with compost and manure to a depth of 3 to 4 inches. Sprinkle the bed with a pound or so of blood meal or hoof and horn meal and work all the amendments into the soil. Rake the bed smooth to remove clods and rocks, and you are ready to plant.

Mix the seeds in a small bowl if you are making your own misticanza mix. Sprinkle the seeds over the bed as you would grass seeds—try to space them about ½ inch apart. Sprinkle fluffy soil or compost over the bed, pat it down, and water the bed in well, being careful not to wash away the seeds. If you have problems with birds or there are many cats in the neighborhood, cover the bed with a floating row cover or bird netting. Anchor stakes in the corners of the beds and tie the netting to them so it is a few inches off the ground. Secure the sides of the row cover or netting with scrap lumber or bricks.

Keep the soil moist until seedlings emerge in seven to ten days. Pull any weeds, but no thinning is necessary. Keep the bed fairly moist, and, depending on the weather, you will have harvestable misticanza greens in six to eight weeks. Either pick individual leaves by hand or take kitchen shears and cut across the bed about an inch above the crowns of the plants. Cut only the amount you want at each harvest. If the weather is favorable, in the 40° to 70°F range, and you keep the bed moist and apply a little fish emulsion fertilizer, the greens will regrow and you can harvest misticanza again in a few weeks.

Garden Blanching Vegetables

Another aspect of Italian gardening that deserves special attention is garden blanching vegetables, sometimes referred to as “forcing.’’

Garden blanching vegetables (as opposed to kitchen blanching vegetables in a pot of boiling water) is a technique whereby light is excluded from all or part of the growing vegetable to mitigate its strong taste. Vegetables that have been blanched are lighter in color and in most cases more tender than nonblanched ones. Vegetables most commonly blanched are asparagus, cardoon, cauliflower, celery, dandelions, some lettuces, and the chicories, including Belgian endive (Witloof chicory), radicchio, escarole, and curly endive (frisée).

To blanch celery (top), the stems are kept from sunlight for a few weeks. Here traditional terra cotta forms are used, but a wrapping of black plastic would also work. Cardoons are blanched in a similar manner. Curly endive (above, left) can be blanched by being held in a tight head with a rubber band or string. This method also works for escarole, dandelions, and cauliflower. Heading chicories (middle) grow in loose heads when young. Once mature, some of the older varieties must be cut back at the crown. They will soon start to resprout (right, bottom) and form a tight head.

We can trace the concept of blanching back several centuries to the time when vegetables were more closely related to their primitive ancestors—which meant they were often tough, stringy, and bitter. Blanching made them both less strong tasting and more tender. Nowadays, most modern varieties are more refined and seldom need blanching, and because forced vegetables are less nutritious and take more hand labor, they are generally less favored. So why blanch vegetables? Basically, because some vegetables have yet to be completely civilized. Cardoon, some radicchios, escarole, dandelions, and some heirloom varieties of celery and cauliflower are all preferable blanched, and Belgian endive can be eaten no other way. And sometimes gardener-cooks blanch vegetables simply to alter the taste for a treat. Thus, for elegant salads, one might blanch endive to make its curly leaves light green and sweet in the center, or dandelion leaves to make them creamy colored, tender, and less bitter.

The blanching process consists of blocking light from the part of the vegetable you plan to eat, be it leaf, stem, or shoot. The blockage keeps chlorophyll from forming, and the vegetable part will therefore be white, very pale, or, in the case of red vegetables, pink. In most cases blanched vegetables are more tender than nonblanched ones.

A few general principles cover most blanching techniques. First, you must be careful to prevent the vegetable from rotting, since the process can create fungus problems. Select only unbruised, healthy plants and make sure not to keep the plants too moist. Such vegetables as cardoon and celery need air circulation around the stalks. Make sure you blanch only a few plants at a time and stagger your harvest because most vegetables are fragile and keep poorly once they have been blanched. Thus, you would not blanch your whole crop of cardoon, escarole, or endive at one time. After you harvest your blanched vegetables, keep them in a dark place, or they will turn green again and lose the very properties you worked to achieve.

Let’s go through the blanching process in detail first with a vegetable that must be blanched to be edible—Belgian endive.

In the fall cut off the tops of the plants to within an inch of the crown and dig up the roots. Once the plants are out of the ground, cut back the roots to 8 to 10 inches. Bury the roots in a bucket in about a foot of damp sand, packing them fairly close together. Store the roots in a dark cellar where it stays between 40° and 50°F. Check occasionally to make sure the sand stays moist; water sparingly when it gets dry. Within a month or so the crowns will start to resprout and produce “chicons” (the forced shoots), which you harvest when they get to be 4 or 5 inches tall. (The newest varieties maintain a tight head without being held in place by sand. Old varieties must have 4 or 5 inches of damp sand packed around the new shoots to hold them in a tight chicon.) The plants usually resprout at least once, and sometimes you can harvest them a third or fourth time. Some of the “forcing” radicchios can be blanched in the same way. In mild-winter areas both types of chicories can be blanched in the garden. Start the plants in midsummer, cut them back to the crown in early fall, build a temporary wooden box around the bed, and blanch them by covering the garden bed with 6 to 8 inches of sand.

The preferred way to blanch cardoon stalks is to wrap the stalks with burlap or straw, surround the bundles with black plastic, and then tie them with string.

To blanch cauliflower, after the curds start to show through the leaves, gather the leaves and tie them up with soft string or plastic strips to cover the emerging head. Other vegetables can be blanched in a somewhat similar way. Blanch dandelions by loosely tying up the leaves and covering the plant with a flowerpot for a week or so, or cover the bed with 4 or 5 inches of sand. The flowerpot process also works well with some of the leaf chicories and is occasionally used for romaine lettuce.

Serve these blanched vegetables with ceremony and give them special treatment. Most are quite mild and are best featured with light sauces and, because they are so tender, short cooking times.

interview

the Sebastiani vegetable garden

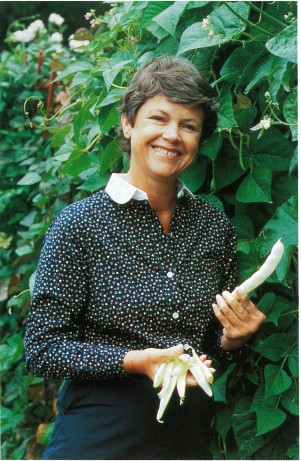

Vicki Sebastiani and her husband, Sam, are owners of Viansa Winery in the Sonoma Valley of California. Vicki has been a vegetable gardener since the age of four. I visited Vicki a number of years ago to see her garden, renowned for its beauty and bounty. When I spoke with her, Vicki’s garden contained a hundred varieties of vegetables and herbs (most of them Italian), including red and yellow varieties of Italian tomatoes, white eggplant, Italian yellow and light green zucchini, giant cauliflower, variegated and red chicories, and her favorite, yellow romano beans.

Vicki’s vegetable garden was a special place. It was designed with long stone planter boxes arranged in a somewhat informal oval-shaped area. The garden had benches and wrought-iron archways planted with scarlet runner beans and was bordered by a low stone wall and rose garden on one side and an inlaid stone patio and a small pond on the other. The vegetable garden was the focal point of the area, and visitors enjoyed wandering through the garden as well as viewing it from the patio tables when dining. Vicki said that most people had never seen many of the vegetables she grew.

Vicki Sebastiani’s garden in the Sonoma Valley of California (left). It’s mid-summer, and the tomatoes and beans are in full production and the cutting chicories and chard are filling in ready for the fall harvest.

To plant her Italian vegetable garden, said Vicki, “In late winter I send away to specialty seed companies for authentic varieties of Italian vegetable seeds. I order my American varieties from both large, well-known seed companies and small companies that carry heirloom and hard-to-find varieties, and I glean the Italian varieties from some of the large American companies, plus poring over some of the specialty seed company catalogs. I purchased a few of the Italian varieties when I was in Italy and ordered others from an Italian seed company, Fratelli Ingegnoli.”

To get a jump on the season, Vicki starts her tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, squash, basil, chicories, and cardoon in flats early in the spring so that she can transplant them into the garden after all chance of frost has passed. As the soil starts to warm up in spring, she plants the seeds of some of the early vegetables, such as lettuce, beets, carrots, fava beans, endive, arugula, and fennel. In early summer she starts the leaf chicories for fall harvest, and a little later the broccolis for the next spring harvest.

The plants Vicki grows reflect a rich heritage of vegetables that are at the heart of Italian cuisine. To give you an idea of this vast range of vegetables, as well as the huge selection of Italian varieties unfamiliar to Americans, these are some of her favorites: romanesco broccoli, both the bronze and the chartreuse types; a purple spouting broccoli; ‘Pepperoncini’ peppers for pickling; ‘Roma’ and ‘San Marzano’ tomatoes for sauce; white and green varieties of pattypan squash; black salsify; the peppery arugula; many chicories, including ‘Palla Rossa,’ ‘Castelfranco,’ ‘Treviso,’ and a Catalonian type; three varieties of Italian chard; white and purple eggplant; Italian parsley; yellow and green romano beans; and a type of large vining zucchini that produces long, meaty fruits with almost no seeds.

Vicki uses her garden vegetables for everyday eating, as well as for the many visitors the Sebastianis have at the winery. The vegetables become part of an antipasto or minestrone or, in many cases, are simply steamed or boiled lightly and served with olive oil and Parmesan cheese. As Vicki said,“When you start with superior vegetables picked at the peak of perfection, they’re very special in themselves.”

Vicki harvests cardoon (above), a close relative of the artichoke. Instead of eating the flower buds of this dramatic plant, the succulent stems are enjoyed.

The Sebastiani garden (right) is located off their patio. The raised stone planters and archway make it an elegant setting for entertaining. The beds contain the last of the spring peas, leeks, onions, and many varieties of eggplants. Scarlet runner beans grow over the archway.