Before setting off across an ocean it is worth considering how to cope if the electrical system fails. Most modern cruising yachts are now heavily reliant on electronics, and therefore need a functioning electrical system in order to navigate safely. Some yachts carry a ‘back-up’ sextant on board, but relatively few have both the reliable skills and the necessary supporting information (such as Air Tables) to use one very effectively, least of all in a crisis. But skippers are responsible for doing all they can to ensure the safety of their crew. It is certainly worthwhile taking the trouble to gain a working knowledge of how to use a sextant to establish latitude at least by a noon site (or quantify the change in latitude from a previously logged position). This simple skill, which can be self taught with a little practice using books readily available from nautical bookshops, is likely to greatly reduce the level of uncertainty of an Estimated Position (EP).

It is advisable to keep a backup handheld GPS with spare batteries inside a waterproof bag and within a metal box (or the oven, but remember to remove before baking) for lightning protection. This is likely to resolve the vast majority of navigational equipment failures. Handhelds can be battery hungry but need only be switched on once a day for a position. Have a paper passage chart onboard and make sure that you keep a paper log of your daily position.

In the unlikely event that a backup GPS fails or the GPS system goes down for an extended period, it is worth remembering that people have successfully navigated across the Atlantic Ocean without electronics, mechanical logs or sextants for hundreds of years. The situation is far from disastrous. The primary concern is likely to be whether you are carrying sufficient water and food for a potentially longer time at sea. A worst case scenario in this respect would be if you encountered electrical wipe-out on route to Bermuda if you had planned to stop and re-provision there or, similarly, if you experience problems on route to the Cape Verdes.

Any vessel on the trade wind route is likely to arrive in the Caribbean sooner or later. This is proved almost every year when abandoned yachts turn up on the windward shores of Caribbean islands several weeks or months after being left at sea. As long as you have kept a paper copy of your passage log and have a paper passage chart, you should have some idea of your position and likely track. But even without these, if you continue in a westerly direction, away from the sunrise and towards the sunset, you will make landfall.

This is a trickier situation as the winds and currents are not so steadfast. You will wish to avoid Bermuda and may not arrive at the Azores. However, you are very likely to make landfall somewhere on the coast of Europe. Again, as long as you have kept a hand-written log and have a passage chart you should have some idea of your position and likely track.

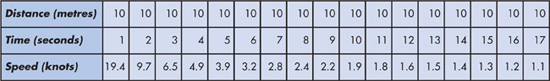

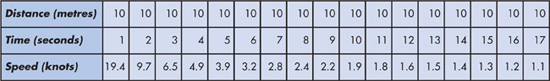

Whichever direction you are heading, navigate by dead reckoning (DR). Use a compass (or the sunrise if there is nothing else) to maintain and record your direction. In the absence of a mechanical log, any small floating object can be used to check the speed of the boat through the water. Record the time (in seconds) it takes to travel 10 metres back after dropping it from the bow and then use the table (below).

You will have to estimate any effect of current from the information given on routeing charts and by comparing the record of boat log with GPS log prior to losing the electronics. The assistance given by the effects of current may be considerable for both westward and eastward crossings and must be considered when estimating days to run before landfall.

A MW radio (perhaps a wind-up one kept in a grab bag for just such an emergency) can be very useful. Tuned to a local frequency and turned on from time to time you should start picking up stations at around 30 to 40 miles during daylight hours. This distance can be considerably increased or decreased by some atmospheric conditions – it tends to be increased at night. Once you have tuned in to a station, the aerial inside the set (not the telescopic one on top) will be surprisingly sensitive to the direction it is pointed in. The best signal will usually be when the flat front or back of the set is pointing directly at the transmitter (in other words you are likely to have good reception with the radio either facing the transmitter or with its back to the transmitter). Given that you should know the approximate direction of the nearest land, you should be able to work out the direction of the transmitting station. At one time a radio to be used in this way was a legal requirement for all Barbados fishing boats. They just followed the signal home.

The main concern will be making safe landfall. You should have some idea of your position from your dead reckoning, but it is a good idea to assume that you are one or more days closer, depending on how long you have been estimating position. The Caribbean islands and the European coast tend to be very well lit and it is likely that you will see the loom of lights from at least 40 miles in good visibility. Clouds tend to form over land and can be a good indicator during the daytime, particularly over the more mountainous islands. You are likely to see an increase in bird activity and may notice varieties of coastal birds. Off the whole of the coast of Europe you may notice a change in sea colour and you will encounter fishing fleets and commercial vessels in increasing numbers as you approach land. So you should have plenty of notice of your approach whether it is day or night. Modern equipment has led most of us into an impatient approach to making landfall. If you are in a less certain position it makes good sense to heave-to during the night. Aim to close the shore in daylight.

The normal availability of GPS makes it easy for a crew to practise emergency navigation by DR, EP and Sextant and then check the accuracy of their results. Doing so will make them familiar with the routine, help to mark the progress of the passage, and be one thing less to worry about if the electrics do fail. Some crew might relish turning their daily fixes into a competition with daily awards or ‘booby-prizes’.