The Negev

King Solomon’s Mines and the market at Be’er Sheva are not the only sights in the Negev – there are magnificent craters, nature reserves, and a high-tech university

Main Attractions

The very name “Negev” conjures up an image of the rugged outdoors, jeeps, camels, frontiersmen – an unforgiving expanse of bleak wastes, sunlight, and sharp, dry air. It is every bit as vast and intimidating as it sounds, containing 60 percent of Israel’s land area but less than 10 percent of its population. Yet the Negev is far from barren: it supports successful agricultural communities, a sprawling “capital”, a complex desert ecosystem, and – since Israel relinquished the Sinai in 1982 – a variety of defense activities.

The Hebrew word means “parched”, and the Negev is indeed parched, with rainfall varying from an annual average of 30cm (12in) in the north to almost zero in Eilat. But don’t expect white sand and palm trees. The northern and western Negev is a dusty plain slashed with wadis: dried-up riverbeds, which froth with occasional winter flash floods. To the south are the bleak flint, limestone, chalk, dolomite, and granite mountains, with the Arava Valley to the east dividing them from biblical Edom, today part of Jordan.

The Visitors’ Center at Mitspe Ramon.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

History

The Negev is saturated with history. In Abraham’s time, around 2000 BC, the area was inhabited by nomadic tribes. When the Children of Israel left Egypt (around 1280 BC) the warlike Amalekites blocked their path to the Promised Land. Joshua eventually conquered Canaan and awarded the Negev to the tribe of Simeon, but only the northern part was settled. King David extended Israelite rule over the Negev in the 10th century BC, and his son Solomon built a string of forts. Solomon also developed the copper mines at Timna, and the port of Etzion Geber (Eilat). After the division of the kingdom into Israel and Judah, the area was occupied by the Edomites, who were expelled by the Nabateans in the 1st century BC.

In the Middle Ages the Negev was an important Byzantine center. In subsequent centuries it remained the domain of nomadic Bedouins until the start of Zionist immigration in the 1880s. But it was not until 1939 that the first successful kibbutz, Negba, northwest of Be’er Sheva, was established. Three other outposts in the western Negev were created in 1943, and a further 11 were thrown up on a single day in 1946.

The Jews fought hard for the inclusion of the Negev in the new State of Israel, and the UN partition plan awarded most of it to the Jewish state. The rest was won in the War of Independence of 1948, when the Egyptian and Transjordanian armies were expelled.

David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, believed passionately in the development of the Negev. When he retired he went to live in what was then a tiny isolated kibbutz, Sde Boker, where he is also buried.

Capital of the Negev

Be’er Sheva 1 [map] still has something of its old frontier atmosphere: brash, bustling, and bursting with energy. You don’t see too many suits or ties here.

The municipal center is reached directly from the northern entrance to the city center but the Old City, farther east, remains the heart of the town. Here, in Ha’atzmaut Street, the Negev Museum (Sun–Tue, Thur 10am–4pm, Wed noon–7pm, Fri–Sat 10am–2pm; tel: 08-699 3535) has been renovated. The unusual rectangular formation of its streets was the work of a German engineer who served with the Turkish Army in the years before World War I.

TIP

A rail link to Be’er Sheva was opened in 2001, with stations at the university and city center. There is a direct link to Tel Aviv. Change at Lod for Jerusalem.

Today, with a population of 205,000, a flourishing industrial base, a university, hospital, medical school, music conservatory, dance school, an orchestra, and arts center, Be’er Sheva is Israel’s fourth city. If it’s a mess, it’s a triumphant mess. Be’er Sheva is the capital of the Negev, providing services for the surrounding population. The regional offices of the companies extracting potash, phosphates, bromide, magnesium, salt, and lime are all here, alongside new factories for everything from ceramics to pesticides. Be’er Sheva has got in on the high-tech act, too, with an advanced technology park in Omer, 10km (6 miles) north of the city, near the affluent suburb of the same name.

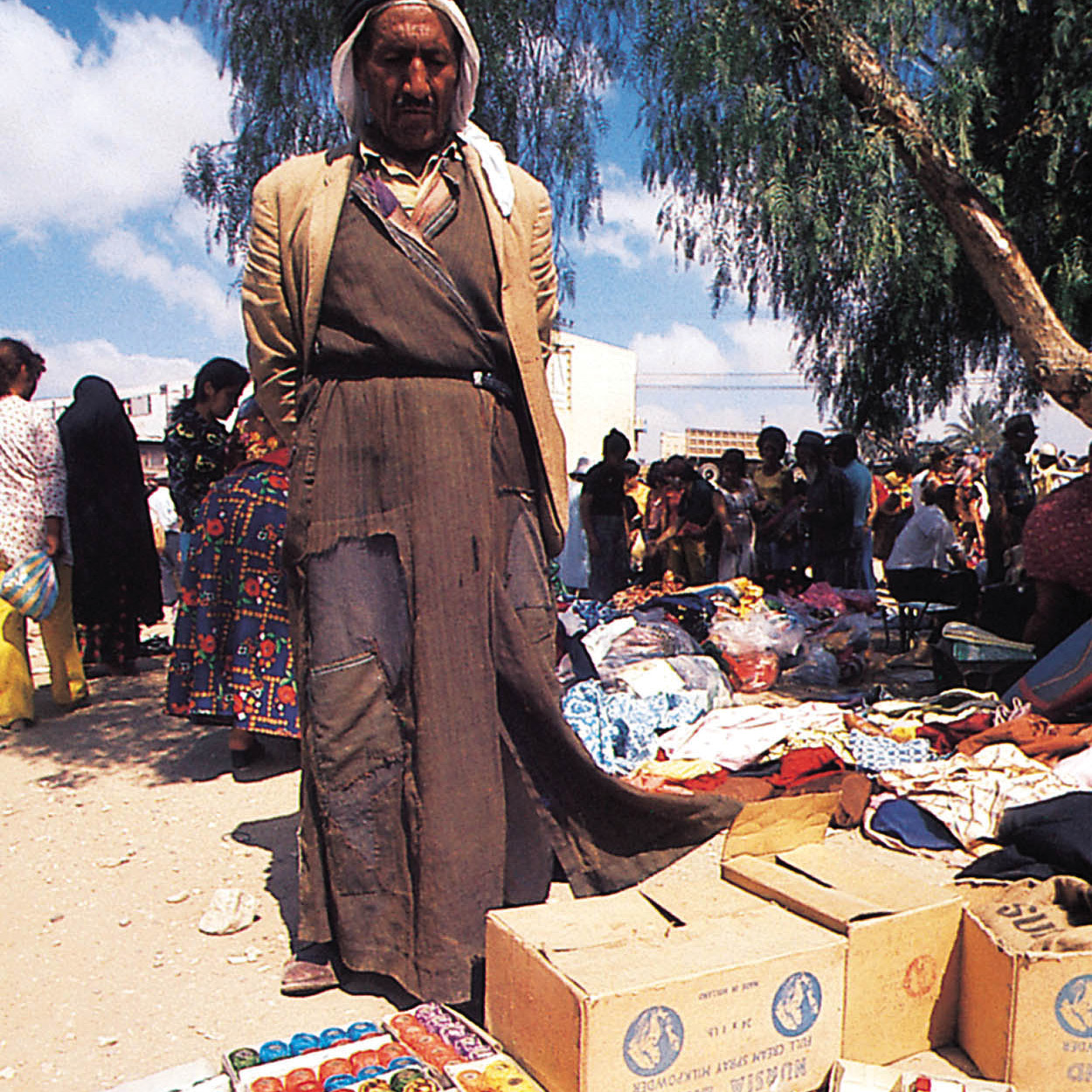

A Bedouin trader at the weekly market.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

The town accommodates people from more than 70 countries, the earlier immigrants from Romania and Morocco rubbing shoulders with more recent arrivals from Argentina, the former Soviet Union, and Ethiopia. An Arab town until 1948, it is now a predominantly Jewish community, but several hundred Bedouin have moved here from the surrounding area and form an important part of the population.

TIP

To learn more about Bedouin culture, travel to the Joe Alon Museum of Bedouin Culture – 24km (15 miles) north on Highway 40 and east along 325 to Lahav (Sat–Thur 8am–4pm, Fri 8am–1pm; tel: 08-991 3322; www. joealon.org.il; charge).

City sights

Every Thursday morning there is a Bedouin market on the southern edge of town, for which a special structure has been built. The Bedouin still trade their camels, sheep, and goats here, but in recent years the market has become a tourist attraction, providing opportunities to buy all kinds of arts and crafts.

Rare blooms.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

The name Be’er Sheva means “well of the covenant”, in memory of the covenant between the patriarch Abraham and a local ruler, Abimelech, in which Abraham secured the use of a well to water his flocks. There is a dispute as to the location of the actual Well of the Covenant. The traditional site is at the bottom of the main street in the Old Town, but more recently archeologists have suggested that it is the 40-meter (130ft) well excavated at the site of Tel Be’er Sheva, some 6km (4 miles) east of the modern city.

The futuristic library at Be’er Sheva’s Ben Gurion University.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

Ben Gurion University of the Negev (www.bgu.ac.il) is one of Israel’s largest universities, with 19,000 students. The university has transformed the town from a desert backwater into a modern community, with its own sinfonietta orchestra and light opera group. The university is doing much to aid understanding of the desert environment, with major projects on water resource management and the ecology of arid regions.

About a mile to the northeast, overlooking the city (near Omer on Highway 60), is the Khativat ha-Negev Monument to the Palmach, which captured Be’er Sheva in the War of Independence. Designed by sculptor Dani Karavan, who spent five years on the project, its trenches, bunkers, pillboxes, and tower (through which visitors are encouraged to climb and crawl) create a claustrophobic atmosphere evocative of a siege. The sinuous concrete edifice is a worthy commemoration of the bitter battle for the Negev between the Egyptian Army and the fledgling Israeli forces backing the kibbutz outposts during the 1948 war.

South of the monument is an animal hospital, attached to the life sciences department of Ben Gurion University. It includes a camel clinic.

Bedouin living.

© Israel by Blake-Ezra Cole / Alamy

The Negev Bedouin

Southeast of the hospital, next to ancient Tel Be’er Sheva, is Tel Sheva 2 [map], a modern village built for the local Bedouin. It is the first of five Bedouin villages in the Negev gradually replacing the traditional tented camps of the nomads, which, as a rule, are spread out over a large area. High-walled courtyards separate the houses, in an attempt to preserve as much privacy as possible.

The New Bedouin Villages

Israel’s Bedouin claim large tracts of the desert over which they formerly grazed their herds, but the lands were never registered, and this has led to disputes with the government. In some cases the Bedouin have been given title to the land around their camps. Where the land has been appropriated by the government, as with Nevatim Airforce Base east of Be’er Sheva, monetary compensation has been awarded. But at present 40,000 Bedouin, about one quarter of the Negev Bedouin, are fighting for government recognition of some 38 “unrecognized” villages. Although the campaign is bearing fruit, with the government recognizing Bedouin ownership of the land in many villages, the Negev tribesmen must then continue fighting to be connected to basic utilities like water, sanitation, and electricity.

The concept was developed by an Arab architect, and its logic seemed unassailable. But in fact the Bedouin were not keen on Tel Sheva and have steadfastly refused to move either there or into similar new towns proposed by the government. Subsequent developments are encouraging the former nomads to build their own homes.

Ancient Tel

Several kilometers before Tel Sheva is Tel Be’er Sheva National Park (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 08-646 7286; charge). Tel Be’er Sheva was recognized in 2005 as a Unesco World Heritage Site, along with Tel Megiddo and Tel Hatzor in the north. This tel sits near the confluence of the Be’er Sheva and Hebron Rivers, where settled land meets the desert. Archeologists working at Tel Be’er Sheva have uncovered two-thirds of a settlement from the early Israelite period (10th century BC), when a fortified administrative city was built on the tel. The site has unparalleled importance for the study of biblical-period urban planning.

The meticulously planned waterworks are evidence of tremendous engineering expertise. The centerpiece of the water system is a huge rectangular shaft dug 15 meters (50ft) into the ground. The walls of the shaft are tiled with pieces of stone. The shaft descends into a large reservoir, fed by the floodwater that flowed through the Hebron River. A 70-meter (230ft) well, Israel’s deepest, was also discovered on the site. Large parts of the ancient buildings have been reconstructed, using mud blocks. Visitors will want to see the well, the city streets, the storehouses, the public buildings and private homes, the city wall and gates, and the reservoir. Especially interesting is the reconstructed horned altar, parts of which were found on the site. There is also an observation tower.

FACT

The soil in the Eshkol region is called loess – a type of very fertile sand that is great for growing winter crops like tomatoes and cucumbers, as well as melons and peppers.

The western Negev

Immediately west of Be’er Sheva along Highway 2357 is Kibbutz Khatserim, where modern drip irrigation was invented. Just past the kibbutz is the Khatserim Air Force Museum (Sun–Thur 8am–5pm, Fri 8am–1pm; tel: 08-990 6853; charge), which records the history of the Israel Air Force and exhibits the aircraft that enabled the country to consolidate its presence in the region.

West from Be’er Sheva along Highway 25, the Negev is flat and dull, more suitable for settlement than for tourism. It is an area of cotton and potatoes as well as extensive wheat fields, irrigated by the run-off from the National Water Carrier, which ends in this area.

The first Negev kibbutzim were built in this region in the 1940s, and, after the peace treaty with Egypt, some of Israel’s northern Sinai settlements were moved to Pithat Shalom (the Peace Region) next to the international border in 1982. East of these communities along Route 241 lies the Eshkol National Park (Ha-Bsor; daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 08-998 5110; charge), 3,300 hectares (750 acres) of trees, lawns, and playing fields with an amphitheater, a swimming pool, and a natural pond, surrounded by cat-tails and cane and stocked with fish.

The Western Negev road, which goes south from this region, is designated as a military area as it is right on the Egyptian border, and travelers using it have to fill in forms provided by the military. Since the peace treaty with Egypt in 1978 it is not regarded as dangerous, but the army wants to know who is using it so that travelers are not stranded there after dark. The southern sector of the road winds attractively through the Negev mountains, providing some spectacular views of Sinai to the west and the Negev to the east.

The ancient site of Mamshit.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

Shivta

There is a road (number 222) from Eshkol to the junction at Mash’abei Sade, just past the Revivim Observation Point. This road passes the former Nabatean settlement of Khalutsa. From Mash’abei Sade, follow the road toward the Egyptian border and you will come to Shivta 3 [map], to the south in the Korkha Valley, a Nabatean city later rebuilt by the Byzantines in the 5th century. An Arab tribe, the Nabateans dominated the Negev and Edom in the first centuries BC and AD. Although less accessible than Ovdat, Shivta is still relatively well preserved, with three churches, a wine press, and several public areas still intact. There is also a direct route here from Be’er Sheva. Shivta, together with the region’s other three Nabatean settlements – Ovdat, Mamshit, and Khalutsa – were also named a Unesco World Heritage Site in 2005, called the incense or spice route.

Nitsana 4 [map], 25km (16 miles) farther west at the intersection of the western highway, is one of two active border crossings to Egypt (Sun–Thur 8am–4pm). The village also located at Nitsana – a desert outpost that now has a thriving school for new young immigrants and a seminar center for desert science – was founded in 1987 and lies just next to the border.

To reach Eilat from Nitsana, you can continue down the road, which hugs the Sinai border, but there are two other main routes to the pleasure resort on the Red Sea. From Be’er Sheva the main highway leads down the eastern side of the Negev, through the Ha-Arava, and that is the one to take if your aim is simply reaching the sunny beaches. Alternatively, a narrow, beautiful, scenic road goes right through the middle of the desert. The traveler may well feel that the Negev between Be’er Sheva and Eilat is a mythical badland dividing Israel from the Red Sea paradise to the south, but there is plenty to see on both routes.

Large and Small Craters

Ha-Makhtesh Ha-Gadol (Large Crater) and Ha-Makhtesh Ha-Katan (Small Crater) are natural geological faults near Dimona and southeast of Yerukham that form part of a trio of impressive geological formations, together with Mitspe Ramon, sometimes known as the Great Crater. The Large Crater is 14km by 6km (8.5 by 3.5 miles) across and 410 meters (1,345ft) deep, and resembles a moonscape. It is best viewed from Mount Avnon, which is 700 meters (2,300ft) high. The Small Crater is 8km by 7km (5 by 4.5 miles) across and 400 meters (1,312ft) deep. Although less extensive, it is more beautiful and accessible, with geological layers in some locations exposed like a rainbow cake: the stone and sand range in color from silver, brown, and yellow to red, purple, and white.

The origin of the craters is unknown. One theory ascribes the Negev craters to volcanic activity, while another theory put forward (discounted by most scientists) suggests the fall of large meteors in the distant past.

To reach the Small Crater, travel on Highway 25 east of Dimona for about 40km (25 miles). A minor road leading south to the Small Crater is marked; the road is located 5km (3 miles) west of the junction with Highway 90.

Geological strata in Mitspe Ramon.

Israel Tourism

FACT

Known locally as Kemahin by the Bedouin, the desert around Nitsana yields truffles each March, when local people can be seen scouring the land for the highly prized food.

Nuclear Negev

The eastern route takes you past the moshav of Nevatim, settled in the early 1950s by Jews from Cochin in southern India. Even within the kaleidoscope of the Israeli population these beautiful, dark-skinned people stand out as “more different” than others. In the past few years they have become famous for growing winter flowers, exported by air to Europe. This industry, which takes advantage of the mild desert climate, has been taken up by others and become a major Israeli export.

Farther east, the development towns of Yerukham and Dimona, built in the mid-1950s, were settled primarily by immigrants from North Africa. Yerukham has a park, 10km (6 miles) south of the road, which is a rare green patch in the arid gray-brown wasteland, but so far the dust tends to dominate the man-high trees. Nearby is an artificial lake, created by a dammed wadi, fed by the winter rains. A huge variety of birds migrate across the Mediterranean coast from Africa to Europe in the spring and return in the autumn; Israel is one of their favorite way-stations.

Dimona is home to the fierce, harsh desert climate that many thought would prove too much for people to live and work in. The few original settlers have now blossomed into a town of 38,000. Although it’s called the “Flower of the Desert,” Dimona is known more for its nuclear plant, Black Hebrew community, and not least its most famous son, soccer star Yossi Benayoun, than for its flora. A small Indian-Jewish community also resides here, and their delicatessens supply great Indian spices and poppadums.

Southeast of Dimona, on Highway 25, the dome of Israel’s infamous Nuclear Research Station looms on the plain behind its numerous protective barbed-wire fences.

FACT

Nitsanei Sinai (Kadesh Barne’a), on the Sinai border, was the only one of Solomon’s fortresses to be rebuilt.

Nearby is the site of Mamshit 5 [map] (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 08-655 6478; charge), called Kurnab by the Arabs. A fine example of a Nabataean site of the 1st century AD, it contains the remains of two beautiful Byzantine churches and a network of ancient dams. The settlement was also famous for breeding Arabian horses. Nearby is the Camel Farm of Mamshit, home to the original ships of the desert. It is still worth a visit even if this alternative mode of travel is not to your taste. Safaris, 4-wheel-drive tours, rappelling and hiking are among the other options.

South of the road is Ha-Makhtesh Ha-Gadol (The Large Crater) 6 [map], a speccular geological fault (take 206 to the south and then 225). Farther east is Ha-Makhtesh Ha-Katan (The Small Crater; see box).

TIP

If you are going into the Tsin Valley as an independent traveler, remember that it should be negotiated very slowly in a 4-wheel-drive vehicle, or else on foot.

A spectacular road

The old road south – today a dirt track – cuts through the desert south of the small crater, connecting with the Arava Valley via Scorpions’ Pass. The most spectacular road in the southern desert, it plunges down a series of dizzying loops that follow each other with frightening suddenness. To the right are the heights of the Negev, great slabs of primeval rock, slammed together. Below are the purple-gray lunar formations of the Tsin Valley, with the square-shaped hillock of Ha-har rising up from the valley floor. Be warned: the rusty metal drums that line the road have been unable to prevent accidents.

The main road from Mamshit (Highway 25) reaches the Arava Valley south of the Dead Sea, at the Arava Junction, near the moshav farming village of Neot ha-Kikar. Situated in the salt marshes and utilizing brackish water, it has become one of the most successful settlements in Israel, exporting a variety of winter vegetables to Europe. In the 1960s Neot ha-Kikar was settled by an eccentric group of desert lovers, who established a private company. As initial attempts at farming the area proved less than successful, they set up a desert touring company for trips by camel and jeep to the less accessible locations of the Negev. Those initial settlers eventually abandoned the village, but their company (still called Neot ha-Kikar) continues to thrive, with offices in Tel Aviv and Eilat.

Similar tours are run by the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel, which, among its noteworthy spectrum of activities, offers a four-day camel tour starting at Ein-Yahav, a moshav some 80km (50 miles) south.

The road through the Arava is bordered by the flint and limestone ridges of the Negev to the west; 19km (12 miles) to the east tower the magnificent mountains of Edom in Jordan, which are capped with snow in winter. These mountains change color during the day from pale mauve in the morning, to pink, red, and deep purple in the evening, their canyons and gulleys etched in gray.

To the south lies the Paran Plain, the most spectacular of the Negev wadis, which runs into the Arava. The road twists through the timeless desert scenery before joining the southern stretch of the Arava road on its way to Eilat. You can continue on this route, taking in the Khai Bar Nature Reserve and Timna, but return to Be’er Sheva and take the central desert road through the Negev Plateau.

The fields of Kibbutz Sde Boker.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

An ostrich, one of the biblical animals at the Khai Bar Nature Reserve.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

The Negev Plateau

The most interesting route south is also the oldest and least convenient, but it passes a number of interesting sites, the first of which is Sde Boker 7 [map], some 50km (30 miles) south of Be’er Sheva. Either take Highway 40 south directly from Be’er Sheva or Highway 204 from Dimona and Yerukham. The kibbutz was the final home of David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, and his wife, Paula. Their simple, cream-colored tombstones, which overlook the Wilderness of Tsin, form a place of pilgrimage for Israeli youth movements and foreign admirers. The old man is said to have selected his burial place, with its view of beige and mustard limestone hills, the flint rocks beyond, and the delicate mauve of Edom in the hazy distance.

The Sde Boker College, south of the kibbutz and overlooking Ben Gurion’s grave, is divided into three sections: Ben Gurion University’s Institute for Arid Zone Research coordinates desert biology, agriculture, and architecture; the Ben Gurion Institute houses the prime minister’s papers and records; and the Center of the Environment runs a field school and a high school with an emphasis on environmental studies.

South of the college is Ein Ovdat, (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 08-653 2016; charge) a steep-sided canyon with freshwater pools fringed with lush vegetation. Rock badgers, gazelles, and a wide variety of birds inhabit this oasis, where the water is remarkably cold even in the heat of summer. A swim can be refreshing, but the water is deep and sometimes it is difficult to climb out onto the slippery rocks. Lone hikers should not take the risk, and parties of visitors should take it in turns, leaving some out of the water to haul out their companions. There are paths up the sides of the cliffs, with iron rungs and railings.

Desert Precautions

Although the Negev and Judean Desert comprise most of Israel, the land expanse is negligible compared with North Africa, North America, and other parts of the world. The nearest gas station is never going to be more than 30km (18.5 miles) away. Even so, never let the tank get too low, and remember there are a few remote areas without cellphone coverage, or where your phone may flip over to the Jordanian network.

Always have plenty of spare water for both the car and yourself. If you go hiking in the desert, make sure you drink plenty of water, keep yourself well covered from the sun, and be aware of what time the sun sets.

Other dangers include flash flooding between October and April. Make sure you listen to the weather forecasts, and if floods are expected, stay clear of dry wadi beds when hiking and heed warning signs on low points on the road. In winter, the desert remains hot during the day but is freezing cold at night. Much of the desert is an army firing zone, with restricted areas well signposted. Poisonous snakes and scorpions are relatively rare, but don’t go looking for them under rocks.

The giant Mushroom Rock.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

Reconstruction at Ovdat

A few kilometers farther south is Ovdat 8 [map] (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 08-655 1511; charge) the site of the Negev’s main Nabatean city, built in the 2nd century BC. Situated on a limestone hill above the surrounding desert, Ovdat was not only excavated but also partly reconstructed in the early 1950s. With its impressive buildings, burial caves, a kiln, workshop, and two Byzantine churches, it is one of the most rewarding sites in the country; what makes it fascinating, though, is the reconstruction of Nabatean and Byzantine agriculture.

With their capital at Petra (today in Jordan), the Nabateans’ achievements in farming the desert are unsurpassed. Their technique was based on the run-off systems of irrigation. Little rain falls in this part of the desert, but when it does, it is not absorbed by the local loess soil; it cuts gulleys and wadis, running in torrents to the Mediterranean in the west and the Dead Sea and the Arava in the east.

A botanist, Michael Evenari, working with archeologists and engineers, has reconstructed Ovdat and two other farms, growing a variety of crops without the help of piped water: fodder, wheat, onions, carrots, asparagus, artichokes, apricots, grapes, peaches, almonds, peanuts, and pistachios are among them.

What started as research into ancient agriculture has proved to be relevant to the modern era, as the system could provide valuable food crops in arid countries of the developing world using only existing desert resources, thus preserving the delicate ecological balances. Indeed, although the ancient Nabateans managed to grow grape vines here 2,000 years ago, they didn’t irrigate them with salt water. New scientific research using saline water has begun to reap rewards in the form of Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon Blanc.

EAT

Kibbutz Yotvata produces some of the best dairy products in Israel. Try some at the cafeteria beside the gas station.

Mitspe Ramon

A half-hour south of Ovdat is the town of Mitspe Ramon 9 [map], percheat an elevation of 1,000 meters (3,300ft) along the northern edge of the Makhtesh Ramon, the largest of the three craters in the Negev (40km/25 miles long and 12km/7 miles wide). Despite its vast size, the crater comes into view quite suddenly – and it’s an awesome sight. Among the finds have been fossilized plants and preserved dinosaur footprints dating back 200 million years to the Triassic and Jurassic periods. Mitspe Ramon has an observatory, connected with Tel Aviv University, which takes full advantage of the dry desert air. In the Makhtesh Ramon a geological trail displays the melting-pot of minerals present in the area, evident from the patches of yellow, ocher, purple, and green that tint the landscape.

Start off at the Mitspe Ramon Visitors’ Center (Sun–Thur 8am–-4pm, Apr–Sept until 5pm, Fri 8am–4pm; tel 08-658 8691; charge) at the edge of town, which not only explains about the crater’s unique geological formations but also offers a splendid view.

From here the road snakes south, joining with the eastern route near the Jordanian border just before Ktura. The next stop is at Kibbutz Yotvata, 50km (30 miles) north of Eilat, with the fascinating Khai Bar Nature Reserve ) [map] (Sun–Thur 8.30am–5pm, Fri–Sat 8.30am–4pm; tel: 08-637 6018; buy tickets at the Visitors’ Center). At this unusual game park, conservationists have imported and bred a variety of animals mentioned in the Bible which had become extinct locally: wild asses, ostriches, and numerous varieties of gazelle. A holiday village, with modest but comfortable accommodation, swimming pools, and a mini-market, is on-site, as is the Arava Visitors’ Center, with a museum and audiovisual display of the desert. Ktura, a kibbutz 16km (10 miles) to the north, offers horse riding.

Timna

Timna ! [map], 24km (15 miles) farther south (Sat–Thur 8am–4pm, Fri 8am–1pm; July–Aug Mon–Thur, Sat 8am–8.30pm, Fri, Sun 8am–1pm; tel: 08-631 6756; www.timna-park.co.il; charge) is the site of King Solomon’s Mines, a little to the south of the modern copper mine. The ancient circular stone ovens for roasting the copper ore look simple enough, with stone channels to the collection vessels for the metal, but the air channels were skilfully angled to catch the prevailing north wind, which comes down the Arava. The late archeologist Nelson Glueck, who excavated the mines, called the ventilation system “an ancient example of automation.”

The area surrounding the mines has been developed as a privately owned park, with an artificial lake and a fine scenic route in the northeast of the park to facilitate touring. Highlights include King Solomon’s Pillars, a natural formation of Nubian sandstone, and the redoubtable Mushroom Rock, a granite rock shaped like a mushroom. The time-worn remains of a settlement, a fortress, and two Egyptian sanctuaries used by the ancient mine-workers can also be seen. From here, it’s just 30km (18 miles) to Eilat and the Red Sea.