The Galilee and the Golan

This tour takes in the Christian landmarks of Nazareth, mystic Safed of the Kabbalah, the Roman baths of Tiberias, and the forbidding heights of the Golan

Main Attractions

A white-robed Druze puffing away on his pipe in a mountain-top village; a bikini-clad bather soaking in sulphuric springs at a Roman bathhouse: these are the stark contrasts typical of Israel’s dynamically diverse north – the Galilee and the Golan.

Extending from the lush Jezreel Valley to the borders of Lebanon and Syria, this relatively compact region, at one moment a desolate expanse of bare rock, can suddenly explode into a blaze of unusual blood-red buttercups and purple irises. Here Christians can retrace the steps of Jesus, while Jews can reflect on the place that produced their greatest mystics.

Lying on the main artery that linked the ancient empires, the Galilee has been a battleground for Egyptian Pharaohs, biblical kings, Romans and Jews, Christians and Muslims, Britain and Turkey.

Jewish pioneers established the country’s first kibbutzim here. In subsequent decades the kibbutzim have mushroomed to cover much of this region, where tribes of Bedouin still live and Arab and Druze villages lie nestled in the hills. A circular tour of the entire Galilee and Golan covers less than 400km (250 miles) – a day’s leisurely drive – but even over the course of a one-month tour the visitor would get only a passing appreciation of this region’s incredible history, sacred sites, diverse inhabitants, and breathtaking landscapes.

Lotem Valley in springtime.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

The valley

Highway 65 from the center of the country suddenly dips into the Jezreel (Izre’el) Valley, which, stretching from the Samarian foothills in the south to the slopes of the Galilee in the north, holds the title of Israel’s largest valley. Because of its strategic location on the ancient Via Maris route, the list of great battles that have scoured this seemingly tranquil stretch is a long and colorful one. However, the greatest battle of all has yet to be fought here. It is the one that the Book of Revelation says will pit the forces of good against the forces of evil for the final battle of mankind at Armageddon.

The site referred to is Tel Megiddo (Mount Megiddo) 1 [map] (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-659 0316; charge), a 4,000-year-old city in the center of the valley. Turn left at Megiddo Junction onto Highway 66 and the Mount is 2km (1.3 miles) to the north.

Even the first written mention of Megiddo – in Egyptian hieroglyphics – describes how war was waged on the city by a mighty Pharaoh some 3,500 years ago. Since then many a great figure has met his downfall on this ancient battleground. It is said of the Israelite King Josiah, who was defeated at the hands of the Egyptians around 600 BC: “And his servants carried him in a chariot dead from Megiddo” (I Kings 10:26). In World War I the British fought a critical battle against the Turks at Megiddo Pass, with the victorious British general walking away with the title Lord Allenby of Megiddo.

In the heap of ruins that make up the tel (mound) of Megiddo, archeologists have uncovered 20 cities. At the visitors’ center a miniature model of the site gives definition to what the untrained eye could see as just a pile of stones, breathing life into what is actually a 4,000-year-old Canaanite temple, King Solomon’s stables (built for 500 horses), and an underground water system built by King Ahab 2,800 years ago to protect the city’s water in times of siege. Steps and lighting enable easier exploration of the 120-meter (390ft) tunnel, and of the almost 60-meter (200ft) high shaft, which was once the system’s well.

Beit She’arim

Head north along Highway 66 through the pleasant but unremarkable countryside of the Jezreel Valley and turn right at Hatishbi Junction onto Route 722 and right again several kilometers later onto 75. You will soon reach Beit She’arim 2 [map] (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-983 1643; charge). This is Israel’s version of a necropolis and was the most important burial place in the Jewish world during the Talmudic period. The limestone hills have been hollowed out to form a series of catacombs. Inside the labyrinths, vaulted chambers are lined with hundreds of sarcophagi of marble or stone (depending on the social rank of the deceased). Each of the coffins – often elaborately engraved – weighs nearly 5 tonnes. When the Romans forbade the Jews to settle in Jerusalem, the center of Jewish national and spiritual life moved to Beit She’arim, and this 2nd-century burial ground became a chosen spot not only for local residents but also for Jews everywhere.

It’s worth climbing the hill for a good view of the Jezreel Valley and the Carmel mountain range. On the hilltop is a bronze statue of Alexander Zeid, who discovered the necropolis in the 1920s.

Back along Route 75, right on 77 and right again along 79 is Tsipori 3 [map] (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-656 8272; charge), known to the Greeks as Sepphoris. Reflecting this settlement’s long history are a 4,500-seat Roman ampitheater, a beautifully preserved 2nd-century mosaic of a woman dubbed “the Mona Lisa of the Galilee,” and a Crusader fortress.

Tensions in Nazareth

When Pope Benedict XVI visited Nazareth in May 2009 a banner condemning those who insult the Prophet Mohammed stretched across a wall near the Basilica of the Annunciation. While the banner referred to an insensitive 2006 speech by the Pope implying that Mohammed was violent, it also reflected the bitter divisions between Muslims and Christians in Nazareth. In 1999 there were riots when the city’s Muslims unveiled plans to build a large mosque opposite the basilica. A compromise was eventually reached and a very small mosque built. Nazareth is a microcosm of the Christian plight throughout the Middle East. Once Christians were a clear majority in Nazareth, but their lower birth rate and higher emigration means that today only 35 percent of Nazareth’s 70,000 residents are Christian.

Crucifixes for sale in the market in Nazareth, a town synonymous with Christianity.

Daniella Nowitz/Apa Publications

Cradle of Christianity

Further along Highway 79 is Nazareth 4 [map] (www.nazareth.muni.il), a strange blend of the timeless and the topical, the sacred town where Jesus Christ spent much of his life and which is today a bustling city of more than 70,000, Israel’s largest Israeli Arab city. “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” (John 1: 46). This rhetorical question might seem puzzling today, particularly to millions of Christians for whom Nazareth is equated with Christianity itself. But when it was posed two millennia ago, the only feature that distinguished this village in the lower Galilee was its obscurity.

FACT

The 70,000 Christians and Muslims living in Nazareth have 50,000 new Jewish neighbors in (Upper) Nazareth Illit on the hill overlooking them.

Since then, the quaint village where Jesus grew up has become one of the world’s best-known towns. Today, of almost two dozen churches commemorating Nazareth’s most esteemed resident, the grandest of all is the monumental Basilica of the Annunciation (Mon–Sat 8am–6pm, until 5pm in winter, Sun 2–5pm; tel: 04-657 2401; free). The largest church in the Middle East, it was completed only in 1969, but it encompasses the remains of previous Byzantine churches. It marks the spot where the Angel Gabriel is said to have informed the Virgin Mary that God had chosen her to bear His son. The event has been given an international flavor, and is depicted inside in a series of elaborate murals, each from a different country. In one, Mary appears kimono-clad and with slanted eyes; in another, she’s wearing a turban and bright African garb. Not to be outdone, the Americans have produced a highly modernistic Cubist version of the Virgin.

Nazareth, the country’s biggest Israeli Arab city.

Daniella Nowitz/Apa Publications

In the basement of the Church of St Joseph (next to the basilica) is a cavern reputed to have been the carpentry workshop of Joseph, Jesus’s earthly father.

Some of the simpler churches, however, capture an air of intimacy and sanctity that the colossal Basilica lacks. This is especially so in the Greek Orthodox Church of St Gabriel, nearly a kilometer further north at the end of Maria Road. Upon entering the small, dark shrine you hear nothing but the faint rush of water. Lapping up against the sides of the old well inside the church is the same underground spring that provided Nazareth with its water 2,000 years ago. Another very atmospheric church is the tiny Catholic one, which was previously a synagogue. At one time believed to be the actual building attended by Jesus, it is now thought to have been built on the same site, probably in the 2nd century AD.

Eight kilometers (5 miles) north of Nazareth on Highway 754, nestled among pomegranate and olive groves, is the Arab village of Kafr Kana. Shortly after being baptized, Jesus attended the wedding of a poor family in this town. Here, says St John’s Gospel, he used his miraculous powers for the first time, making the meager pitchers of water overflow with wine. Two small churches in the village commemorate the feat.

Har Tavor (Mount Tabor) 5 [map] rises to the east of Nazareth and south of Kafr Kana, but it is necessary to travel around almost four sides of a square – best east along 77 then south on 65 – to reach this huge hump of a hill. Mount Tabor offers an overview of the whole Jezreel Valley – a patchwork of gold and green farmland. This strangely symmetrical hill dominates much of the valley. It was here that the biblical prophetess Deborah was said to have led an army of 10,000 Israelites to defeat their idol-worshiping enemies. Two churches commemorate the transfiguration of Christ, which is also said to have taken place here.

When his sermons began to provoke the Jews, Jesus took three of his disciples and ascended Mount Tabor. There, the Gospels say, “He was transfigured before them – his face shone like the sun and his garments became white as light.” The Franciscan Basilica of the Transfiguration commemorates the event, which Christians believe was a foreshadowing of his resurrection.

Safed, Town of Legends

The Shulchan Aroch, otherwise known as the basic set of daily rituals for Jews, was compiled in Safed. But the real focus of Safed’s sages was not the mundane but the mystical. Many had been drawn to the city in the first place because of its proximity to the tomb of Rabbi Shimon Bar-Yochai, the 2nd-century sage who is believed to have written the core of the Kabbalah, Judaism’s foremost mystical text.

The efforts of Safed’s wise men to narrow the gap between heaven and earth left not only great scholarly work and poignant poetry but also a legacy of legends about their mysterious powers. At one synagogue (Abohav) an earthquake destroyed the entire building but left unscathed the one wall facing Jerusalem.

Jews studying the Kabbalah, Safed.

Robet Harding

Atmospheric Safed

About 30km (18 miles) due north of Mount Tabor are the highest peaks in the Galilee. Many people believe that they exude an inexplicable air of something eternal that makes them seem even higher than they are. Travel north along 65, west along 85, and northeast on 866 to the Meron mountains. To reach the highest peak, Har Meron 6 [map] – at 1,208 meters (3,955ft), the highest summit in pre-1967 Israel – you have to continue on Highway 89 for 11km (7 miles) and turn south onto the mountain road. When not marred by the summer heat haze, the sweeping view from the Mediterranean to Mount Hermon is exceptional. These mountains are filled with the mystery of the tombs of the rabbis who composed the Kabbalah, the now highly fashionable great Jewish mystical texts that have enchanted the likes of pop singer Madonna.

FACT

Safed’s Israel Bible Museum exhibits 300 visual scenes of the Bible by the artist Phillip Ratner. The Kabbalah Museum explains kabbalah teachings. Mila Rozenfeld’s Doll Museum (Eshtam Building) has a collection of costumed dolls. Beit Hameiri is a historical museum documenting Safed’s Jewish community.

At the base of the mountain, back on Highway 89, in Meron village, is the tomb of Shimon Bar-Yochai, the revered rabbi who drew Jews to the region in the first place. On the feast of Lag Ba’Omer in May you can still see tens of thousands of his devout followers gather outside the synagogues of nearby Safed and make their way in a joyous procession to his grave at the foot of Mount Meron.

Immediately southeast of Meron is Safed 7 [map] (www.safed.co.il). This attractive hilltop town can be reached by heading southeast along 89. Sheltered by the highest peaks in the Galilee, Safed seems also to be sheltered from time itself. Its narrow, cobblestoned streets wind their way through stone archways and overlook the domed rooftops of 16th-century houses. Devout men, clad in black, congregate in medieval synagogues, the echo of their chants filling the streets. A modern area of Safed, with some 32,000 residents, has sprung up around the original city core.

When the Spanish Inquisition sent thousands of Jews fleeing, many ended up in Safed, bringing with them the skills and scholarship of the golden age they had left behind in Spain. The rabbinical scholars of Safed were so prolific that in 1563 the city was prompted to set up the first printing press in the Middle East (or, in fact, in all of Asia).

Every synagogue here is wrapped in its own comparable set of legends, which the shamash (deacon) is usually delighted to share. Not all the synagogues are medieval, many of the original ones having been destroyed and replaced by more modern structures, but the spirit of the old still lingers in these few lanes off Kikar Meginim.

The special atmosphere that permeates Safed has captured the imagination of dozens of artists who have made it their home. Like the rest of the Old City, the artists’ quarter of Safed remains untouched. “Nothing has been added for the benefit of the tourist,” is the claim. Nothing has to be. Winding your way through the labyrinth of lanes, you’ll find more than 50 studios and galleries as well as a general art gallery and a museum of printing. Another highlight in Safed is the Klezmer Hasidic Musical Festival each August.

Towering above the center of Safed, littered with Crusader ruins, is Citadel Hill, an excellent lookout point, taking in a panorama that extends from the slopes of Lebanon to the Sea of Galilee.

TIP

Almost all the historical, archeological, and natural sites around the country – there are a dozen mentioned in this chapter alone – are run by the Israel Parks Authority. Entrance to each site costs about US$4 per person. But a US$25 green card gives access to all 56 sites around the country. www.parks.org.il; tel: 02-500 6261 or *3639 from within Israel.

Havens in the hills

The wide open spaces of the Western Galilee (west of Safed) act as a haven, attracting various idealists seeking to carve their own small utopias on its slopes. So, in addition to the more common settlements like kibbutzim, Bedouin encampments, and Arab, Druze, and Circassian villages, you’ll find a community of transcendental meditationists at Hararit who have found their nirvana on these secluded slopes. There is also a colony of vegetarians at Amirim who have set up an organic farm as well as running guesthouses and restaurants where visitors can indulge in gourmet vegetarian meals. The villagers of Harduf also eat only organically grown foods, while Klil’s residents will only utilize energy that is generated by the sun or wind. Shorashim is billed as a pluralistic, egalitarian community belonging to the conservative synagogue movement.

Looking out over the Sea of Galilee.

Daniella Nowitz/Apa Publications

To be sure, even the mainstream Jewish inhabitants of this region tend to lead a lifestyle governed by environmental if not religious concerns. Many have left the crowded center of the country to seek a higher quality of life and fresher air. There are many high-tech opportunities in the region, and the commute to Haifa is only 30 minutes.

Karmi’el 8 [map] has burgeoned into the largest town in the Western Galilee. It was established in 1964, and its population of 45,000 includes native-born Israelis as well as Jewish immigrants from 34 countries (including many Americans and, recently, Ethiopians and Russians). Clean, pretty, and prosperous, Karmi’el is considered a model development town. Near its center, against a backdrop of desolate mountains, is a series of larger-than-life sculptures depicting the history of Israel’s Jewish people. Each July, Karmi’el hosts an International Folk Dance Festival.

Karmi’el is set in the Beit Kerem Valley, the dividing line between what is considered the Upper Galilee (to the north), with peaks jutting up to almost 1,200 meters (4,000ft), and the Lower Galilee (to the south), a much gentler expanse of rolling hills, none of which exceeds 600 meters (2,000ft). This area west of Safed has not been included in the formal route of this tour, but the landscape is spectacular and many of the aforementioned “off-beat” villages offer accommodations.

The Galilee panhandle

Descending eastward from Safed on Highway 89 is the land extending north of the Sea of Galilee, which gradually narrows into what is known as the finger of the Galilee in Hebrew or the Galilee panhandle in English, with Metula at its tip. This is particularly pretty countryside. The east opens up into the sprawling Hula Valley, beyond which hover the Golan Heights. Towering over the valley to the west are the Naphtali mountains, beyond which loom the even higher mountains of Lebanon. These picturesque peaks were in the past a source of frequent Katyusha rocket attacks on the Israeli towns below.

Apart from the beauty it offers, the road to Metula is an odyssey through the making of modern Israel. The first stop on this trek is Rosh Pina 9 [map]. On the rock-strewn barren terrain they found here over a century ago, pioneers fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe set up the first Jewish settlement to be founded in the Galilee since Roman times. They called it Rosh Pina, meaning “the cornerstone”, a name which came from the passage in Psalm 118: “The stone which the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.” The original 30 families who settled here were part of the first wave of Jewish immigration that began in the 1880s.

Rosh Pina, a quaint town of about 1,000, has maintained something of its original rural character. Cobblestoned streets line the old section of the town, and 19th-century houses, though badly neglected, still stand.

Continuing northward toward Metula on Highway 90, the next stop after several kilometers takes you off the road of modern history, exposing instead the far more ancient foundations of the country. Khatsor ha-Glilit (Tel Hazor) (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-693 7290; charge) is one of the oldest archeological sites in Israel – and by far the largest. With its 23 layers of civilization spanning 3,000 years, it was the inspiration for The Source, James Michener’s 1965 novel.

TIP

The fee to Tel Hazor includes free entrance to the museum at Kibbutz Ayelet ha-Shakhar, and visitors are encouraged to stop off at the museum first in order to understand the excavations better. The kibbutz also runs a popular guesthouse.

The Hula Valley

This is the region of the Hula Valley, a stretch of lush land dotted with farming villages and little fish ponds that would seem like a mirage to someone who had stood on the same spot 60 years ago. Then you would have seen 4,000 hectares (10,000 acres) of malaria-infested swamp land – home to snakes, water buffalo, and wild boar.

The draining of the valley was one of the most monumental tasks undertaken by the State of Israel in its early days. It took six years. By 1957 the lake had been emptied, leaving a verdant valley in its place, but now part of the region has been re-swamped, as excessive peat in the ground is impeding agriculture. You can get an idea of what the area was like before the drainage by visiting the 80 hectares (200 acres) of swampland that have been set aside as the Hula Nature Reserve ) [map] (Sat–Thur 8am–4pm, Fri 8am–3pm; tel: 04-693 7069; charge). Three kilometers (2 miles) after Yesod Ha-Ma’ale Junction, turn right into the reserve. There is also a museum devoted to the natural history of the region at Kibbutz Khulata, known as the Dubrovin Farm, just to the south; it recreates living conditions in the late 19th century. There is a guesthouse in the northern part of the valley at Kfar Blum, a kibbutz founded by English immigrants. From just south of Kiryat Shmona on Highway 90, the Manara Cable Car travels 750 meters (2,460ft) up into the Naftali Hills and offers a splendid panorama of the Hula Valley (daily 9.30am–4.30pm; tel: 04-690 5830).

Fruit trees in bloom in the Hula Valley.

Israel Tourism

The nearby town of Kiryat Shmona began life as a series of corrugated iron huts known as ma’abarot (essentially, refugee camps). Situated close to the border, it has been for years the target of rocket attacks and terrorist infiltrations from the Lebanese mountains that overlook it, and the town was devastated by hundreds of missiles during the Second Lebanon War in 2006. Today the town is quiet, with a population of 20,000, but it has little of interest to tourists.

The road to Metula

When the end of World War I left Palestine’s status unclear, Arab gangs attacked the Jews in this most northern region, forcing them out of their settlements. The settlers at Tel Khai and Kfar Gil’adi, north of Kiryat Shmona, though outnumbered, held out under siege for months until their leader, Joseph Trumpeldor, was shot and killed. The incident prompted the Jews to improve their self-defense and triggered the formation of the Haganah, predecessor of the Israel Defense Forces.

The building from which the settlers defended themselves is now a museum devoted to the Haganah. Nearby is a memorial to Trumpeldor and seven fellow fighters, including two women, who died in the attack. Thousands of Israeli youths converge on the Tel Khai site on the anniversary of Trumpeldor’s death. There is also a youth hostel here and a guesthouse at neighboring Kfar Gil’adi, today a flourishing kibbutz.

Just before Metula, in the Nakhal Iyon Reserve (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-695 1519; charge), is a picturesque waterfall that flows impressively in the winter months (Oct–May) but is completely dry the rest of the year. This is due to a longstanding arrangement by which Israel permits Lebanese farmers to divert the water for agricultural use.

The landscape of the Lower Galilee.

© SuperStock

Until the Golan was captured from Syria in 1967, Metula ! [map] (www.metulla.muni.il), Israel’s most northern point, surrounded on three sides by Lebanese land, was the target of frequent rocket attacks. Founded in 1896 by Baron Edmund de Rothschild, who purchased land from local Druze for the same wave of Russian immigrants that had settled in Rosh Pina, it was for two decades the only settlement in the area. Even today, the nearest major shopping center is 10km (6 miles) away in Kiryat Shmona. But one attraction is the Canada Center, the country’s only Olympic-size ice rink.

Apart from the fresh mountain air, abundant apple orchards (much of the country’s supply comes from here) and charming pensions, what draws tourists to this secluded town of 600 inhabitants is its now famous border with Lebanon. Since Israel withdrew from Lebanon in 2000, there is no daily stream of Lebanese workers coming to Israel each day, but the “Good Fence” border offers Israelis an opportunity to stare into the troubled territory of their northern neighbor.

FACT

Kibbutzim aren’t what they used to be. In 2005 Kibbutz Shamir, just west of Kiryat Shmona, raised US$48 million on the US NASDAQ market for its optical industries firm, which makes quality lenses.

The source of the River Jordan

Return to Kiryat Shmona and travel east on Highway 99. Some 10km (6 miles) east of Kiryat Shmona, on the edge of the Golan Heights (and what used to be the Syrian border), is the archeological site of Tel Dan (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-695 1579; charge). Situated at the northern tip of Israel, it was founded in biblical times by members of the tribe of Dan, after quarrels with the Philistines forced them to leave the southern coast. It is also notorious as one of two cities where Jeroboam permitted idolatrous worship of the golden calf.

Today the site includes various Israelite ruins, a Roman fountain and a triple-arched Canaanite gateway. In the summer, volunteers help to excavate this active and scenic tel, where the source waters for the Jordan River emerge in attractive bubbling brooks. The museum at Kibbutz Dan nearby has descriptions of the geology of the region and the reclamation of the Hula Valley below. The kibbutz also runs a very popular restaurant, the Dag on the Dan, specializing in fresh trout from the nearby streams.

The Dan River provides the greatest single source of the Jordan River – in fact, “Jordan” is a contraction of the Hebrew Yored Dan (descending from Dan), and that’s precisely what this biblical river does. For its 264km (165-mile) length, the Jordan flows from the snowy peak of Mount Hermon to the catchment basin of the Dead Sea, 400 meters (1,300ft) below sea level, and the lowest point on the face of the earth.

The Golan in Antiquity

The Golan stands out as having been disputed throughout history. In antiquity it was the greatest natural barrier traversed by the Via Maris, the “Sea Highway” that led from Egypt and the coastal plain across the Galilee and the Golan to the kingdom of Mesopotamia. The Golan was allocated to the tribe of Manasseh during the biblical era, but was frequently lost and recaptured over the centuries. Under Roman rule, Jewish settlement in the Golan increased, and a few generations later, during the Jewish Revolt against Rome (AD66), many of the descendants of those settlers met cruel deaths during the epic battle for the fortress of Gamla. The mountain range changed hands frequently during the following centuries.

Qumran, from the Dead Sea.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Several kilometers further east, the Banias Waterfall @ [map] is among the most popular natural attractions in the country – and has been for thousands of years. “Banias” is a corruption of the Greek Panaeas, and in a cave near the spring are the remains of an ancient temple built in honor of Pan, the Greek god of the forests.

Roman and old Crusader ruins may also be visited at Banias, which is in the Mount Hermon National Park (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-690 2577; charge), but the real attractions are the waterfalls, including the country’s largest, and some inviting pools.

Before 1967, Banias was located in Syrian territory. Thus you are now officially on the fiercely contested Golan Heights. The Golan (www.golan.org.il) is a sombre massif doomed by history and bloodied by almost ceaseless war. It is a great block of dark gray rock lifted high above the Upper Jordan Valley, and those who possess it have the power to rain misery upon their neighbors.

FACT

Many of the ancient buildings in northern Israel are built from black volcanic basalt rock taken from the Golan Heights.

The Golan is a mighty fortress created by the hand of nature. During the Tertiary Age, geological folding lifted its hard basalt stone from the crust of the earth. Today it is a sloped plateau, rising in the north to heights greater than a full kilometer above sea level. It stretches 67km (42 miles) from north to south and 25km (15 miles) from east to west.

Israel considers the Golan Heights to be part of its territory (in 1981 Israeli military occupation of this former Syrian territory was replaced with civil law and administration), although few other countries accept this fait accompli. Israeli justification for absorbing the Golan focused on Syria’s belligerence, and the fact that it was used as a base for artillery shelling of Israeli settlements below.

Since the beginning of the peace process there has been much talk of territorial compromise over the Golan, but many people in Israel vehemently oppose such a move, in particular the 25,000 Jewish settlers on the Golan.

Historic redoubt

The Golan has been disputed throughout history. Archeological evidence indicates a substantial Jewish population until the time of the Crusades; for the next eight centuries, the area was practically desolate.

At the end of the 19th century the Ottoman Turks tried to repopulate the Golan with non-Jewish settlers, to serve as a buffer against invasion from the south. Among those who put down roots here were some Druze, Circassians fleeing the Russian invasion of the Caucasus mountains in 1878, and Turkomans who migrated from Central Asia. A village of Nusseiris (North Syrian Alawites) was also established here.

After World War I, when British troops under General Edmund Allenby drove the Ottomans off the Golan, the region was included in the British Mandate of Palestine, but in the San Remo Conference of 1923 it was traded off to the French sphere of influence. From 1948 to 1967 the Syrians used the Golan Heights as a forward base of operations against Israel. Jewish villages in the Hula Valley were shelled by Syrian artillery mounted here. Syria continued to install fortifications in the Golan throughout the 1960s, converting the region into a military zone.

War finally broke out on June 6, 1967, with Syrian army attacks on Kibbutz Dan, Ashmura, and She’ar Yashuv. The attack was blunted the following day, and on June 9 Israeli troops counterattacked. Within 48 hours all Syrian units on the Golan had either retreated or surrendered.

FACT

The Golan Druze still have strong ties with Syria. Many young people study at universities in Syria and marriages are often arranged, usually between young Syrian Druze women and Golan men. The economic opportunities are greater on the Golan.

From war to peace

Only six inhabited villages, with a total population of 6,400 people, remained on the Golan at the time of the Israeli victory. These included five Druze communities and one Shiite village at Ghajar. Today these villages house more than 20,000 inhabitants, who live peacefully within Israel but have refused to take Israeli citizenship and “pragmatically” speak publicly in support of Syria for fear that they may one day find themselves looking to Damascus as their capital.

Within weeks of the 1967 conquest, members of Israeli kibbutzim began establishing communities in the unpopulated hills, the first of these being Merom Golan. During the following years the region was transformed as orchards were planted with apples, pears, peaches, almonds, plums, and cherries, and vineyards were established.

Syria attacked again on October 6, 1973, the Jewish Day of Atonement. The next day Syrian troops occupied nearly half the Golan. Israel responded on October 8 in what was to become the greatest tank battle in history. Within a week Syria had lost some 1,200 of an estimated 1,500 Soviet-built tanks. By 24 October, Israeli units were within sight of Damascus when the United Nations called for peace, and Israel complied. A dangerous legacy of minefields remains.

Now for more than three decades peace has prevailed. Indeed, this has been Israel’s quietest border, with first President Hafez el Assad and in recent years his son Bashir scrupulously adhering to the armistice agreement signed with Israel in 1975. As a result, domestic tourism to this region, which remains delightfully cool in the summer months, has flourished, although it remains rarely visited by overseas tourists. Ample but unexceptional bed-and-breakfast accommodations have sprung up on most of the region’s settlements.

Most Israelis see the Golan as a vital buffer zone between them and Syria, an enormous bunker filling its ancient role of blocking invasion. But visitors who do come usually tour the old Syrian fortifications that dot the area. The Nimrod Fortress £ [map] (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-776 2186; charge) on the northern Golan – turn left onto Highway 989 from 99 – is one such example. From this 13th-century Syrian fortress, constructed to defend the waters of Banias below, one gains a spectacular view of the Northern Galilee and the Naphtali Hills beyond, and it is easy to understand the strategic reasons for its construction.

FACT

In the winter the adventurous sort will sometimes ski on the Hermon in the morning and drive down to Eilat to go scuba-diving on the same day.

Mount Hermon

Towering above the north end of the Golan is Mount Hermon $ [map] (2,814 meters/9,232ft), with several ranges radiating from it. It occupies an area roughly 40 by 20km (25 by 12 miles) and is divided between Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and several demilitarized zones under UN jurisdiction. About 20 percent of this area is under Israeli control, including the southeast ridge Ketef ha-Hermon (the Hermon Shoulder), whose highest point rises to 2,236 meters (7,336ft).

The higher areas of Mount Hermon are snow-covered through most of the year, and each winter brings snow to all elevations over 1,200 meters (3,900ft). Israeli ski enthusiasts have opened a modest ski resort on these slopes, with a chair-lift and an equipment rental shop for skis, boots, poles, and toboggans. The slopes are often compared to those found in New England – not particularly lofty, but nevertheless a challenge and a pleasure to ski. The ski resort (8am–4pm generally Jan–Apr, depending on snowfall; tel: 04-698 1337) can be reached by continuing along Highway 989 and turning north onto 98 in the outskirts of Majdal e-Shams.

Take in the wildlife of the Golan Heights.

Daniella Nowitz/Apa Publications

Nature on Mount Hermon is of particular interest to Israelis because it’s the only sub-alpine habitat in the country. Several birds, such as the rock nuthatch and the redstart, are at the southernmost extremity of their range here, while others, such as the Hermon horned lark, are found nowhere else.

Many dolinas are scattered around Mount Hermon. These are cavities in the surface of the rock formed by karstic action on the mountain’s limestone. In the winter the dolinas fill with snow, and they are the last areas to melt in the spring, thus supporting lush green vegetation long after the rest of the slope has dried out under the intense sun.

Olive oil factory on the Golan Heights.

Daniella Nowitz/Apa Publications

Druze villages

At the foot of Mount Hermon is Majdal e-Shams % [map], the largest of the Druze villages on the Golan, which is located at the junction of Highways 989 and 98. The town has good restaurants and souvenir shops, and is popular with tourists.

The Druze village of Mas’ada, 8km (5 miles) to the south along 98, overlooks the Ram Pool ^ [map], a fascinating gological phenomenon. This is one of only two extinct volcanos in the world which over time has evolved into a small lake (the other is in Kenya).

FACT

In the English language the eagle is often designated the king of the birds, but in Hebrew it is the vulture that is given this title, outranking the eagle. See the vultures at Gamla and you’ll understand why.

A popular tourist pastime in the spring and summer on the Golan is visiting farms that allow you to pick (weigh and pay for) your own fruit such as cherries, blackberries, and raspberries, which are expensive delicacies in Israel. Among other places, this can be done at Elrom, 7km (4 miles) south of Mas’ada.

Katsrin, 20km (13 miles) southwest along Highway 91, is the modern “capital” of the Golan and the region’s only municipal center. Established in 1977, it is designed in the shape of a butterfly and is home to the Golan Archeological Museum (Sun–Thur 9am–4pm, Fri 9am–1pm, Sat 10am–1pm; tel: 04-696 9634; charge) which exhibits artifacts from the ancient settlement of Katsrin.

With a population of 5,000, Katsrin is the home of Golan Wineries, one of the country’s largest winemakers, which in the 1980s revolutionized the country’s wine industry, previously known for cheap sweet red wine used for religious purposes. For Israelis, Golan is synonymous with good wine and, assisted by Californian experts, it sells US$30 million worth of quality wines a year, including US$5 million in exports. Dozens of other smaller Israeli wineries have taken their inspiration from the Golan venture.

You can visit the Golan winery in Katsrin (Sun–Thur 8.30am–5pm, Fri 8.30am–1.30pm; tel: 04-696 8435; www.golanwines.co.il; free entry and free samples). Teetotallers will prefer the tour of the nearby Mei Eden mineral water factory, also free with free samples (Sun–Thur 9am–4pm; book the tour in advance; tel: 04-696 1050).

FACT

Fish in the Sea of Galilee are so plentiful that catches of 270kg (600lb) don’t make headlines. It is recorded that, in 1896, more than 4,000kg (9,200lb) of fish were caught in one massive net.

Gamla

Another often-visited site on the Golan is Gamla & [map] (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-682 2282; charge). Travel south from Katsrin on 9088, and go left and right onto 808. Gamla was the “Masada of the north,” a fortified town of the south-central Golan which, in AD 66, was the focus of one of the early battles in the Jewish revolt against Rome. Initially, the rebels put Vespasian and three full Roman legions to shame. The over-confident Roman leader threw his troops against the Jewish bastion, only to have them humbled by a much smaller and less professional Jewish force. Recovering, the embarrassed Romans besieged the Jewish town in one of the most bitter battles of the war. Vespasian vowed that no mercy would be shown.

The Griffons of Gamla

The ruins of Gamla are clustered on a steep ridge, and, if you tour the area between late winter and summer, there is a very good chance of seeing magnificent griffon vultures. You don’t have to be an ornithologist to appreciate these impressive creatures, with their 2-meter (7ft) wingspan. Moreover, because the vultures’ nests are just below the hilltop lookout, visitors are given the unusual treat of seeing the birds from above.

There are an estimated 40–45 pairs of vultures here, which makes it the largest flock in the Middle East, and major efforts are made to protect them and help them breed. They are officially listed as a “vulnerable” species, one step above “endangered.” The site also commands a fabulous view of the Sea of Galilee.

The Romans gradually pushed the Jews to the precipice above which this mountain-top city was built, and, when Roman victory appeared imminent, many defenders committed suicide rather than surrender. Four thousand Jews were killed in battle; another 5,000 either committed suicide or were slaughtered by the Romans after Gamla had fallen to them.

“The sole survivors were two women,” historian Flavius Josephus wrote. “They survived because when the town fell they eluded the fury of the Romans, who spared not even babes in arms, but seized all they found and flung them from the citadel.”

The site was reduced to rubble by the Romans and then lost to history for precisely 1,902 years. In 1968, Gamla was rediscovered during a systematic Israeli survey of the region. Today it is possible for visitors to stroll through the ancient streets of this community and inspect the remains of many ancient houses, and even a synagogue, all of which were constructed out of the Golan’s somber black basalt stone.

Among the fields to the east of Gamla it is possible to find several prehistoric dolmens. These are Stone Age structures, which look like crude tables, with a large, flat stone bridging several supporting stones. They are generally considered to be burial monuments, and most are dated to about 4000 BC. Dolmens are found at several other sites around the Golan and the Galilee.

Overlooking the Sea of Galilee.

Daniella Nowitz/Apa Publications

Jewel of the Galilee

Glowing like an emerald, its tranquil surface framed in a purplish-brown halo of mountains, the Sea of Galilee (Yam Kinneret) is probably the most breathtaking lake in the country. At 21km (13 miles) long and 11km (7 miles) wide, with a depth of no more than 45 meters (150ft), it may not be enormous by global standards, but it has, through some romantically inspired hyperbole, come to be known as a “sea” (the Sea of Galilee, the Sea of Tiberias, and the Sea of Ginossar are its most popular names). In Hebrew it is called Yam Kinneret because it is shaped like a kinnor, a harp.

Not surprisingly, these bountiful shores have been inhabited for millennia, with the earliest evidence of habitation dating back 5,000 years to a cult of moon-worshipers that sprouted in the south. Some 3,000 years later the same lake witnessed the birth and spread of Christianity on its shores, while high up on the cliffs above, Jewish rebels sought refuge from Roman soldiers. The dramas of the past, however, have since faded into the idyllic landscape. Today it is new water sports, not new religions, that are hatched on these azure shores.

Qumran, from the Dead Sea.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Around the lake

Descend Highway 869 to the lake and travel anticlockwise along 92 and then 87 to Capernaum. It was in the numerous fishing villages around the Sea of Galilee that Jesus found his first followers. The village of Capernaum * [map] on the northern tip of the lake, became his second home. Here he is said to have preached more sermons and performed more miracles than anywhere else.

It was a metropolis of sorts in its heyday, and at least five of the disciples came from here (it is after one of them, a simple fisherman named Peter, that the Galilee’s most renowned fish gets its name). Today the site houses the elaborate remains of a 2nd-century synagogue – said to be built over the original one where Jesus used to preach. There is also a recently completed church, shaped like a ship, on what was believed to be the house of St Peter, a Franciscan monastery, and the colorful red domed roofs of the Greek Orthodox Church of the Seven Apostles.

FACT

Vered Hagalil Guest Farm (between Tiberias and Rosh Pina; tel: 04-935785; www.veredhagalil.com) was created by Yehuda Avni, who emigrated from Chicago to Israel in the late 1940s, and his Jerusalem-born wife, Yonah. They transformed barren land into a leisure complex.

In the neighboring town of Ein Tabgha, Jesus is said to have multiplied five loaves and two fishes into enough food to feed the 5,000 hungry people who had come to hear him speak. The modern Church of the Multiplication (daily 8.30am–5pm) was constructed over the colorful mosaic floor of a Byzantine shrine in 1982. Next to it stands the Church of Peter’s Primacy.

It was standing on a hilltop overlooking the Sea of Galilee that Jesus proclaimed to the masses that had gathered below: “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.” This well-known line from the Sermon on the Mount is immortalized by the majestic Church and Monastery of the Beatitudes (daily 8am–5pm; free). An octagonal church, it is set in well-maintained gardens, belongs to the Franciscan order and was built in the 1930s.

Moving back south along Highway 90, you will first come to the towering cliffs of Arbel. Today a rock climbers’ haven, during Roman times they served as a hideout for Bar Kochba and his Jewish rebels.

Nearby is Ginosar, an especially beautiful kibbutz with a luxurious guesthouse. Ask some of the residents about the perfectly intact 2,000-year-old boat recently uncovered on the shores of the kibbutz.

Overlooking the Sea of Galilee.

Daniella Nowitz/Apa Publications

Tiberias, a lakeside resort

The capital of the lake, Tiberias (Tverya) ( [map], has beme known for its “fun in the sun” spirit. A sprawling city of 60,000, halfway down the west coast, it is one of the country’s most popular resorts. On its new boardwalk, lined with seafood restaurants, you can dig into delicious St Peter’s fish while enjoying a stunning view of the lake. On the marina you can have your pick of water-skiing or windsurfing, or go for a dip at one of the beaches along the outskirts of the city. During summer you’ll need to dunk yourself in the water one way or another.

With all the distractions available in this popular playground, it’s easy to forget that Tiberias is considered one of the four holy Jewish cities. To remind you, there are the tombs of several famous Jewish sages buried here, including the 12th-century philosopher Moses Maimonides and the self-taught scholar Rabbi Akiva, who was killed by the Romans after the Bar-Kochba uprising.

When it was founded by Herod Antipas around AD 20, Tiberias failed to attract devout Jews because it was thought to be built over an ancient Jewish cemetery and so considered impure. But eventually economic incentives, as well as a symbolic “purification” of the city by a well-respected rabbi, cleared the way for settlement. During the 2nd and 3rd centuries it reached its zenith. With a population of 40,000, it became the focus of Jewish academic life. It was at Tiberias that scholars codified the sounds of the Hebrew script and wrote the Mishnah, the great commentary on the Bible.

By the eve of the Arab conquest of 636, Tiberias had become the most important Christian center outside Jerusalem. A 12th-century battle between Muslims and Crusaders destroyed the city, and, after being resettled, it was again reduced to rubble in 1837, this time by an earthquake. The repeated destruction of the city has, unfortunately, left only sparse remnants of its vibrant past. A few remains of Crusader towers dot the shoreline, and an 18th-century mosque is crammed in between ice-cream stands in the main square.

For historians and hedonists alike, Tiberias’s main drawing-card is the hot springs on the main road, less than a kilometer south of Tiberias city center. There are many hypotheses about what caused this natural wonder. In fact, the same cataclysmic convulsions that millions of years ago carved the Jordan Rift also created these 17 springs that gush from a depth of 2,000 meters (6,500ft) to spew up hot streams of mineral-rich water. The therapeutic properties of the springs have been exploited for centuries.

EAT

The Chinese food at Habayit (The House), opposite the Lido Beach in Tiberias, makes it one of the best restaurants in Israel.

Spa treatments

Opposite is the Rimonim Mineral Tiberias Hotel (formerly Holiday Inn), which offers a range of treatments, from whirlpools to electro-hydrotherapy, that are reputed to cure everything from skin ailments to respiratory problems and, some claim, sterility. In the winter, a soak in these mineral-rich waters can be a soothing respite from the damp Galilee air.

You can see the original baths the Romans built in a fascinating little museum (Sun–Thur 10am–noon, 3–5pm; charge), in the National Archeological Park across the street. Also within this national monument, which is the site of the ancient city of Khamat, archeologists have uncovered a 2nd-century mosaic synagogue floor – undoubtedly the most exquisite ruins you’ll find in Tiberias. Maimonides tomb on Ben Zakai Street, just south of the hotel district, is a popular site for Jewish pilgrims.

Just outside the city, 4km (2.5 miles) to the west along Highway 77, are the Horns of Hittim (Karnei Khitim), where in 1187 the Muslim forces of Saladin defeated the Crusaders in the decisive battle that brought an end to the Crusader Kingdom.

Building a snowman on Mount Hermon.

Jonathan Nackstrand/AFP/Getty Images

Baptism in the Jordan

Shortly after Jesus left Nazareth at the age of 30, he met John the Baptist preaching near the waters of the Jordan. In the river that the Bible so often describes as a boundary – and, more figuratively, as a point of transition – Jesus was baptized. Once thus cleansed, he set out on his mission. One tradition holds that the baptism took place at the point where the Sea of Galilee merges with the Jordan River near what is today Kibbutz Kinneret, 12km (7 miles) south of Tiberias on Highway 90.

The Yardenit Baptismal Site (Sat–Thur 8am–5pm, Fri 8am–4pm; tel: 04-675 9111; www.yardenit.co.il; charge) has been established just outside the kibbutz in order to accommodate the many pilgrims who still converge on the spot. After the Six Day War, the site was closed except for special occasions, but it is now open for more general access. There is also a rival “Site of the Baptism” further south, near Jericho.

Around the point where the lake merges with the Jordan River in the south are three kibbutzim: Dganya Alef, Dganya Bet, and Kinneret ‚ [map]. Not having guesthouses, they attract fewer tourists than other kibbutzim around the lake, but they are the ones that are most worth noting because they were the first in the country. From the ranks of their members sprang many of Israel’s legendary leaders, including Moshe Dayan. At the entrance to Dganya Alef is a Syrian tank, stopped in its tracks in the 1948 War of Independence. Kinneret’s cemetery, on the lakeside by Kinneret Junction, is the burial place for leading Israeli artists and is a marvelous place for tranquil contemplation. The beaches around the lake are expensive and often crowded and dirty.

Several settlements have guesthouses and camping facilities, including Moshav Ramot; Kibbutz Ein Gev, site of a gala music festival every spring; Kibbutz Ha’On, which had an ostrich farm before they became popular in other parts of the world; and Kibbutz Ma’agan. Also on the east coast is the Golan Beach and its water wonderland, the Luna Gal. At Beit Zera, on the southern tip of the lake, are the ruins of an ancient moon-worshiping cult.

Ancient baths dating from the Roman period are found on the southern Golan at Khamat Gader ⁄ [map] (Sat–Thur 9am–5pm, Fri 9am–12.30pm; tel: 04-665 9999; www.hamat-gader.com; charge), near the Yarmuk River, and reached traveling eastward on Highway 98. Set in a secluded mountain nature reserve and with Israel’s only naturally flowing hot mineral springs, Khamat Gader is by far the country’s most popular commercial tourist attraction. The site’s renovated Roman baths and a range of other attractions, including treatments and massages, a water park, a crocodile farm and other animal exhibits, as well as restaurants, draw 500,000 visitors a year. Khamat Gader was established in the 2nd century AD by the Roman Empire’s 10th Legion. The spa soon became recognized as the second-most beautiful baths in the empire, after Baiae in Italy, and was known internationally as the Three Graces – symbolizing charm, youth, and beauty. The baths were badly damaged by an earthquake in the 7th century and eventually abandoned in the 9th. The site also has an exclusive hotel and spa.

Khamat Gader hot springs and resort.

Daniella Nowitz/Apa Publications

TIP

Many kibbutzim, such as Sedot Nehemia, rent out inner tire tubes, on which you can float down the River Jordan – an extremely relaxing experience.

Back along 98 and south on 90 for 30km (19 miles) is the ancient tel of Beit She’an ¤ [map], reflecting 6,00 years of civilization and billing itself as Israel’s Pompeii. Near it in the Beit She’an National Park (daily 8am–4pm, until 8pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-658 7189; charge) sits Israel’s best-preserved Roman theatre, which once seated 8,000; and there is an archeological museum featuring a Byzantine mosaic floor. Beit She’an was once a member of the Roman Decapolis, meaning that it was one of the 10 most important cities in the Eastern Mediterranean. Other structures here include a colonnaded street, on the east side of which is a ruined temple that collapsed in an earthquake in the 8th century. Excavations have revealed 18 superimposed cities, so those in search of archeological intrigue should not miss Beit She’an.

Beit She’an’s Roman theater.

Israel Tourism

The modern town, however, is a rather dull little place with little to offer. If you’re thinking of going to Jordan, there is a Japanese-funded crossing here called the Jordan River Crossing, opened in 1999 and sometimes known as the Sheikh Hussein Bridge. It is 90 meters (nearly 300ft) long.

Easily accessible from the highway north of Beit She’an are the impressive ruins of the 12th-century Crusader fortress of Belvoir (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-658 1766; charge). Perched on the highest hill in the region, it offers an extensive view of the valleys below and of neighboring Jordan.

TIP

Israelis flock to the Gilboa mountains in March for fleeting glimpses of the rare and distinctive Gilboa iris, symbol of the Society for Protection of Nature in Israel.

South of Beit She’an and east of the Gilboa mountain range is one of the lowest points in Israel: the Jordan Rift. Encompassing the Jordan Valley and the Beit She’an Valley, it is part of the same 6,500km (4,000-mile) rift that stretches from Syria to Africa and is responsible for the lowest point on earth – the Dead Sea. Even here, at 120 meters (390ft) below sea level (it gets to 390 meters/1,280ft further south), it’s like a kiln baking under an unrelenting sun during the summer. By way of comparison, Death Valley, California, the lowest point in the United States, is only 87 meters (285ft) below sea level. But nourished by the Jordan River, the Yarmuk River, and a network of underground springs (including the Spring of Kharod), this remains a lush region, bursting with bananas, dates, and other fruit. It is home to some of Israel’s most prosperous kibbutzim.

A water system not quite as historic as Megiddo’s but impressive in its own way can be found at Gan ha-Shlosha (The Garden of Three) ‹ [map] (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-658 6219; charge), west along 6667 from Bet She’an. Modern developers have managed to recreate a tiny piece of Eden in this stunning park. It is also known as Sachne, meaning “warm” in Arabic, because of the warm waters of Ein Kharod (The Spring of Kharod) that bubble up from under the earth to fill a huge natural swimming pool.

The Spring of Kharod actually starts at the foot of the Gilboa mountains, just southeast of Afula, and flows all the way to the Jordan, but for most of the way the warm waters are underground and diverted for use in local settlements. The only other spot where they surface is at Gid’ona, where the Israelite warrior Gideon supposedly assembled his forces 3,000 years ago, and which in more recent times served as the training spot for the forces of the Palmach, the elite fighting unit of the Jews before the State of Israel was created.

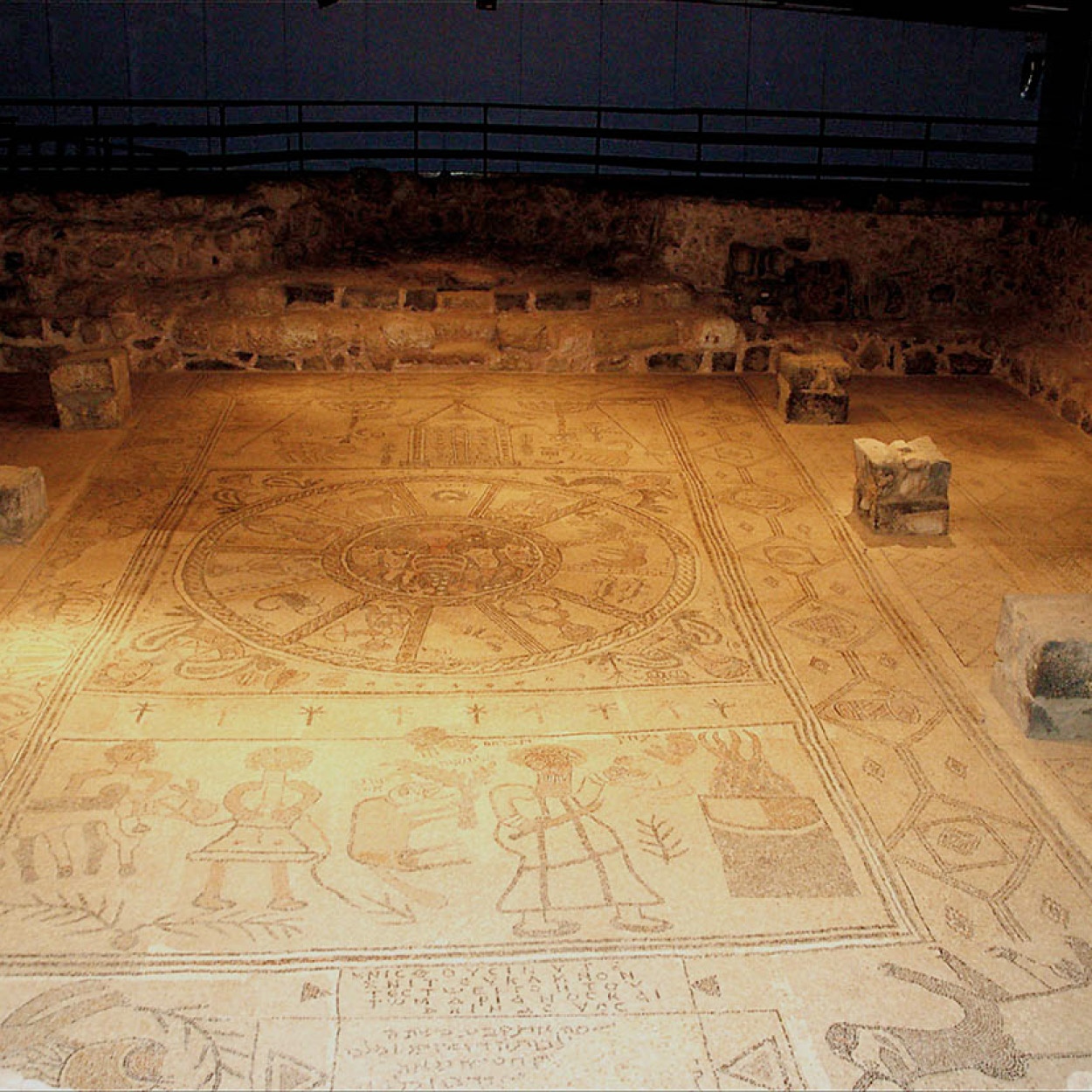

The Zodiac mosaic at Kibbutz Beit Alfa.

Israel Tourism

Uncover millennia of civilization at Beit She’an.

Israel Tourism

About a mile west of Gan ha-Shlosha is Kibbutz Beit Alfa (daily 8am–4pm, until 5pm Apr–Sept; tel: 04-653 2004; charge), where you’ll find the country’s best-preserved ancient synagogue floor. Discovered when kibbutz members were digging an irrigation channel, the 6th-century floor consists of a striking Zodiac mosaic and a representation of the sacrifice of Isaac.

Overlooking the length of the Jezreel Valley are the Gilboa mountains. Here King Saul met his untimely end at the hands of the Philistines, causing David to curse the spot forever: “Ye mountains of Gilboa, let there be no dew, nor rain upon you, neither fields of choice fruit” (II Samuel 20: 21–3). Return to Afula and travel eastward on 65 to Megiddo.

Israeli Wine Makes its Mark

Over the past two decades, Israeli wine has become something to take seriously. Quality wines have taken their place on the nation’s table, pushing aside the sweet red wines that were once produced for religious benedictions. The once poor condition of Israeli wine was not helped by the fact that vineyards were initially planted along the humid coastal plain. In recent decades, Israel’s wineries have found that viticulture is an art best practiced in the chillier, drier inland hills of the Golan Heights and Galilee, the Judean Hills, and the Negev highlands.

The establishment of state-of-the-art wineries and importing know-how and the finest vine stock from France, California, and Australia has seen the local industry bloom. Most of all, the enthusiasm of a new generation of wine growers, and an ever-increasing, discriminating, and affluent local market have enabled over 200 companies, most of them boutique wineries, and another 100 small family winemaking farms, to make their mark on the local scene. Israeli wines have also developed an international reputation, winning prizes in overseas competitions. Some US$30 million worth of Israeli wine is exported annually and is available mainly in locations with large Jewish communities.

Winemaking is as ancient as the Old Testament. The grape was one of the seven biblical species and the Kiddush sanctification and drinking of wine before Sabbath and holiday meals has been a pillar of Judaism down the centuries.

The largest Israeli winery is Carmel Wines, established in 1882 by French Jewish philanthropist Baron Edmond de Rothschild. The Golan Heights winery founded in 1983 set new standards by introducing California know-how, while Israel’s other major winery, Barkan, traces its history back to 1899, although the modern winery was built in 1988. These big three control 80 percent of Israel’s domestic market.

Before the 1980s wine revolution, the most popular grapes cultivated were Emerald Riesling, Semillon, and Colombard for whites, and Petite Syrah, Grenache, and Carignan for red and rosés. When wine-growing shifted to the hills, new varieties were introduced such as Chardonnay, Muscat, and Sauvignon Blanc for whites and Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, and Zinfandel for reds and rosés to name but a few.

The proliferation of vineyards has transformed the Israeli countryside with the rich green rows of vineyards etched across hillsides in the otherwise dusty summer landscapes.

Traveling or trekking for the more adventurous across wine trails has become a popular Israeli pastime and there are potential routes in five regions, which include history, archeology, and breathtaking landscapes: the Galilee and the Golan, the Carmel region, Central Israel, the Judean Hills, and Negev.

Suggested wine routes for tourists include the Judean Hills west of Jerusalem – travel along Road 38 south of Beit Shemesh through the Haela Valley, where David, it is believed, slew Goliath. There are eight wineries (four on each side) in close proximity to the highway: from north to south on the west side at Mony, Tzora, Teperburg, and Agur, and on the east side at Katalav, Ella Valley, and two Hans Sternbach Vineyards. http://www.mil-media.co.il/wine/winejerusalem.htm.

In the Galilee, travel north of Tsefat along Road 89 to the Yashfe Wineries, and then along Road 886 to the Dalton, Miles, and Rimon Wineries, while further north along Road 889 is the Galil Mountain Winery. http://www.mil-media.co.il/wine/winegalil.htm.