The great majority of animal species are invertebrates, i.e. lacking a spinal supporting axis. They range from microscopic, single-cell protozoa to highly complex animals such as insects and spiders. The more advanced animals are loosely called “higher” invertebrates and the less biologically complex ones “lower” invertebrates.

Of the 23 major divisions (phyla) of invertebrates, only four have members that can be regarded as southern African wildlife:

• Molluscs: snails and slugs (most of the 80 000 species of molluscs worldwide are marine animals and account for the millions of seashells found on beaches)

• Annelids: earthworms and leeches

• Onychophora: velvet worms

• Arthropods: invertebrates with jointed limbs

This chapter deals with those invertebrates that are likely to be encountered by the naturalist and are not included in the chapters on insects and spiders. These include the commonly found terrestrial snails, both earthworms and leeches, the velvet worm or Peripatopsis, and the important terrestrial arthropods (other than spiders and insects, which are described in subsequent chapters). Crustaceans, millipedes and centipedes are also included in this chapter. The main orders within each class are described.

All other invertebrates fall outside the scope of this book. However, some are of medical or economic importance and, for the sake of comprehensiveness, the remaining invertebrate phyla are listed below:

Protozoa: |

single-cell animals |

Mesozoa: |

minute parasitic worms |

Porifera: |

sponges |

Coelenterata: |

jellyfish, sea anemones, corals |

Ctenophera: |

comb jellies |

tapeworms and flukes, such as bilharzia (Schistosoma) |

|

Nemertinea: |

ribbon worms |

Entoprocta: |

minute stalk-like tubes |

Aschelminthes: |

parasitic roundworms such as Ascaris worm in humans |

Acanthocephala: |

spiny-headed worms |

Bryozoa: |

moss animals |

Phoronida: |

mud-tube worms |

Brachiopoda: |

lamp shells |

Sipunculoidea: |

peanut worms |

Echiuroidea: |

sausage-like marine worms |

Chaetognatha: |

arrow worms |

Echinodermata: |

starfish, sea urchins |

Pogonophora: |

beard worms |

Hemichordata: |

tongue worms |

Lower invertebrates are so widely diverse that few aspects of their biology are common to the group as a whole.

Slugs and snails are confined to moist habitats and nocturnal activity or to periods of relatively high humidity. They move by means of undulating contractions of the muscular foot. Mucus is laid down to lubricate their passage.

Although hermaphrodite, pairs of individuals crossfertilise by simultaneously transferring sperm into each other. Eggs are deposited in damp hollows and hatch into fully formed miniature adults. As the snail grows, the shell is enlarged by adding to the spiral.

Earthworms move through the soil by consuming it and squeezing it in waves of contraction through the body. Organic food is ingested in the process.

Although hermaphrodite, individuals come to the surface to crossfertilise, each partner coming halfway out of its burrow. They position themselves side by side, their heads pointing in opposite directions, and secrete a mucous sheath that binds them together for as long as three or four hours. In this position, sperm is exchanged via grooves that run along the surface of each worm’s body. After they separate, each worm secretes a mucous ring which slides over the body. As it passes over the openings of the sperm receptacles it receives sperm. Fertilisation thus takes place within the mucous ring which, when it eventually slips off the head of the worm, forms a “cocoon” and is left amid leaf litter on the surface of the ground. Typically, not all the eggs in a cocoon hatch and those that do not are absorbed by the few young worms that do develop. There are no larval stages and the young worms resemble miniature adults.

Leeches move over surfaces by attaching the rear sucker, extending the body, attaching the front sucker and then releasing the rear and contracting the body again. Aquatic species swim by undulating their flattened bodies. The parasitic leeches attach themselves to their hosts and suck blood and body fluids from them. Some remain permanently attached to their hosts, others drop off after feeding. Scavenging and predatory forms have a proboscis which they can wrap around food such as a small worm, and so pull it into the mouth. Some leeches are able to tide over the dry winter months in protective cocoons.

Leeches are hermaphrodites but, because their male and female reproductive systems are active at different times, crossfertilisation occurs after a brief mating in the warm months. Eggs are laid in a cocoon and buried in the mud or attached to submerged vegetation. Some attach the cocoon to themselves or to the animals they parasitise. Certain species even brood the eggs and young which, in all species, hatch as miniature leeches and grow by moulting.

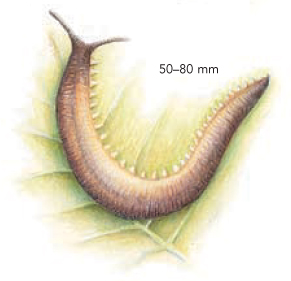

Velvet worms (e.g. Peripatopsis) feed on wood lice and other arthropods on the forest floor. They defend themselves by ejecting two fine jets of sticky fluid which form an entanglement of threads for about 20 cm in front of the worm. This effectively wards off attacks by aggressive predators and may help to immobilise prey. Velvet worms have survived for 500 million years and may have been the first creatures to venture from the sea onto land.

Mating is unique in the animal kingdom. Males deposit adhesive sperm packets randomly on the skin of the female. The skin ruptures and the sperm enters the body and finds its way to the ovaries. The young are born after a gestation period of about 13 months.

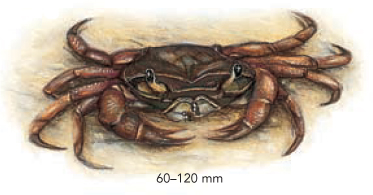

Terrestrial crustaceans include two very different forms: freshwater crabs and wood lice.

Freshwater crabs are common along rocky streams and ponds, but move far from water during wet weather. They have a strong sense of smell with which they both scavenge and hunt for food. They are common in slow-flowing streams and vleis of the summer rainfall parts of South Africa.

They mate “face to face” and the eggs, which are fertilised internally, are carried by the female on specially modified appendages on her second to fifth abdominal segments. Female crabs carrying eggs are said to be “in berry” and may be encountered in the warm months. Unlike most of their marine relatives, freshwater crabs have no larval stage and the young which hatch are miniature adults. The young crabs fend for themselves and grow by progressive moults in which the hard outer layer of the body is shed, allowing the animal to increase its body size.

VENTRAL ASPECT OF FRESHWATER CRABS

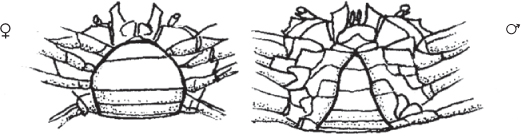

Wood lice, in adapting to terrestrial life, have had to economise on water use. They lack the waxy skin-covering present on most other land-living arthropods and therefore select cool, damp areas and are mostly active at night. They breathe principally by means of gills which they must keep moist. To do this, some species have developed a special technique of squeezing water out of damp vegetation by pressing their backs against it. Their habit of rolling up into a tight ball, although functional for defence, is also thought to cut down on evaporative water loss by reducing the exposed surface area.

After mating, usually in the warm months, the females carry the batch of small spherical eggs with them in a special brood pouch, or marsupium, formed by flat projections on the underside of the body. After hatching, the young grow by successively shedding the toughened external skeleton.

Centipedes are solitary predators, immobilising their prey with formidable poison claws. They move with a snake-like motion and are capable of running relatively fast. If molested, they wriggle violently in an attempt to shake off the attacker. Some types have the last pair of walking legs modified into stout pincer-like appendages with which to defend themselves as they retreat into a hiding place.

Breeding generally occurs in spring and early summer. Courtship is very brief and simple and mating consists only of the male attaching a small spermatophore to the female. Fertilisation takes place at a later stage and the eggs are laid in a hollow. In many species, the mother curls around them protectively.

Millipedes are entirely vegetarian and lack poison appendages for attack or defence. In defence they coil up and secrete offensive fluids, containing cyanide, from spiracles along the midline of the body.

Mating pairs intertwine to allow the male to deposit a spermatophore onto the female. In pill millipedes the male creates a squealing sound by stridulation to induce the female to uncoil and accept the spermatophore. After mating, eggs are laid in the soil, deposited in capsules amid humus. Some species make receptacles out of regurgitated material or dig a nest chamber in which the spherical white eggs are left. Newly hatched millipedes have only eight segments and three pairs of legs, and grow by moulting the skin and adding segments with legs to the rear end of the body immediately in front of the final segment.

Dimensions given with the illustrations in this chapter refer to body length, from head to final segment. Soft-bodied animals, such as leeches, are measured in a natural, extended position.

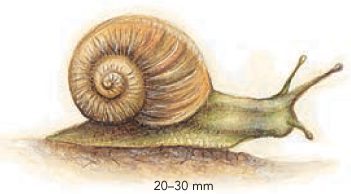

1 GARDEN SNAIL

Two pairs of tentacles, one pair long with eyes at tips, one pair short. Body light grey to cream. Shell light brown with dark brown streaks and spots. Mouthparts (radula) used to scrape away leaf tissue. Snails are hermaphrodites but mate to exchange sperm. Eggs are deposited in the soil and young hatch during wet season. Introduced from Europe. Common in gardens in moist areas, mostly in disturbed habitat.

Similar

HERBIVOROUS SNAILS Genus Sheldonia

Smaller (about 10 mm). Body darker, black in parts.

Natalina cafra

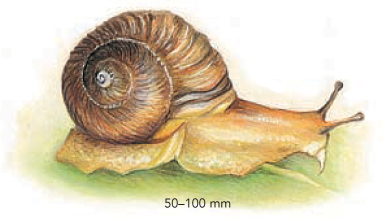

2 CARNIVOROUS SNAIL

One pair of tentacles bearing the eyes. Fleshy palp present either side of mouth. Shell large, olive-green to brown with fine ridges crossing the whorls. Body colour light yellow. Feeds on other snails, earthworms. Pulls snail out of shell, eats it and absorbs some of the calcium from the shell for strengthening its own shell. Hermaphrodite, but mates to exchange sperm. Lays several white, pea-sized eggs. Eggs hatch after several weeks. Coastal strip from southwest to southern Mozambique, never more than 250 km inland.

Similar

LESSER CARNIVOROUS SNAIL Nata vernicosa

Smaller (about 10 mm). Shell pale brown.

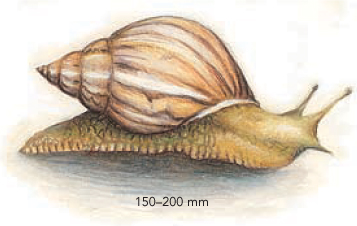

Achatina fulica

3 GIANT AFRICAN SNAIL

Two pairs of tentacles, larger pair bearing eyes at tips. Smaller pair located either side of mouth. Shell conical, cream or pale yellow with dark brown stripes. The largest land snail. Dead shells often seen in veld. Feeds on plant matter, carrion. May eat whitewash off walls to obtain calcium for shell construction. Lays several hundred pea-sized yellow eggs which hatch after a few days. Warm, low-lying areas.

Genus Stylommatophora

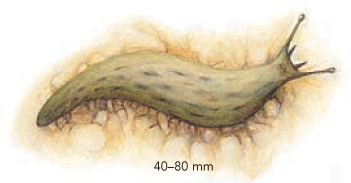

4 SLUGS

Two pairs of tentacles, one pair longer. Eyes at tips of longer pair. Body flattened on top. Moist, slimy, with small bumps along upper surface. Breathing hole sometimes clearly visible. Found only in moist, dark habitats under stones or leaf litter. Feeds on fresh plant material. Absence of shell is thought to be an adaptation to low levels of calcium available on land. Hermaphrodite, but mates to exchange sperm. Moist forest habitats throughout southern Africa.

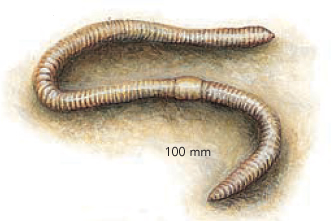

1 COMMON EARTHWORM

Body cylindrical. Outer surface smooth, moist. Slightly swollen band encircles body about one-third of the way from head. Pale brown. Juveniles occur near surface, adults from surface to several metres down. Constructs burrows by eating soil and plastering digested material against walls. Introduced. Widespread except in dry areas.

Similar

There are numerous indigenous species, often with very local distribution. Some reach several metres in length.

Class Hirudinea

2 LEECHES

Body flattened on top and below, tapering towards head. Suckers present at head and tail. Sucker at head is smaller. Body smooth, glossy black. In shallow, vegetated, calm water. Attaches to fish and mammals, sucks blood. Anticoagulant is secreted to prevent clotting at site of attachment, causing excessive bleeding when leech is removed. Swells to many times original size while feeding. Hermaphrodite, but mates to exchange sperm. Warmer parts of southern Africa. Terrestrial leeches absent from the region.

Phylum Onychophora

3 VELVET WORMS (PERIPATOPSIS)

Short antennae easily visible. Body covered in small bumps which detect wind and touch. Large number of fleshy legs tipped with claws. Pinkish-brown. Found under logs and stones or along stream banks. Feeds on snails, insects, earthworms. Confined to moist forests in south and along east coast. Represents evolutionary link between earthworms and arthropods.

Order Decapoda

4 FRESHWATER CRABS

No antennae. Eyes on stalks. Body brown. Five pairs of limbs: four pairs of legs, one pair of pincers. Inhabits streams and shallow fresh water. Burrows into banks and forages from there, feeding on detritus. Male and female mate facing each other. Female carries eggs until they hatch. Throughout southern Africa.

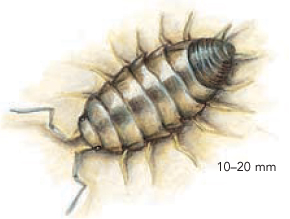

Order Isopoda

5 WOOD LICE

No antennae. Body flattened top and bottom. Seven pairs of legs. Dull to dark grey. Avoids light, seeks out humid habitats under stones and in leaf litter to reduce water loss. Feeds on algae, fungi, moss, decaying plant matter. Eggs brood in water-filled cavity in female. Throughout southern Africa, particularly in moist areas.

Similar

SAND HOPPERS Order Amphipoda

Body flattened laterally. Legs of unequal length.

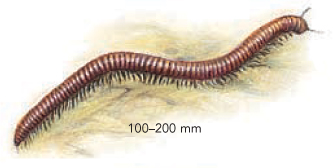

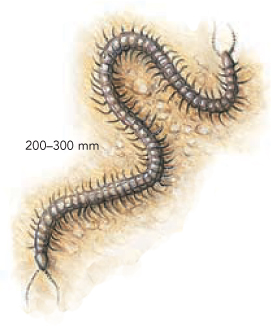

1 WORM-LIKE MILLIPEDES

Antennae short. Head tucked in, pointing downwards. 40-60 segments. Glossy black or with alternating yellow and black bands. Up to 120 pairs of legs. Feeds on decaying plant material and fungi. Female lays several hundred pinhead-sized eggs. Young hatch with three pairs of legs, acquiring more at each moult. Throughout southern Africa, less common in dry areas.

Similar

KEELED MILLIPEDES Order Polydesmoidea

About 20 segments. Keels on sides, concealed legs.

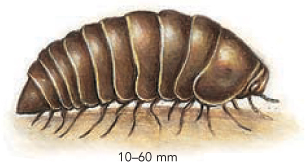

Order Oniscomorpha

2 PILL MILLIPEDES

Antennae easily visible. 12 segments which are smooth, shiny. 21 pairs of legs covered by lateral extensions of segments. Rolls into sphere when disturbed. Feeds on decaying plant matter, lichens, moss. Female lays about 20 eggs. Young hatch with three pairs of legs, acquiring more at each moult. Confined to moist forests.

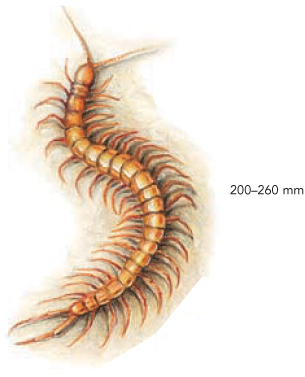

Order Scolopendromorpha

3 LARGE CENTIPEDES

Antennae one quarter body length. 25 pairs of legs, equal in length to width of body, last pair long with conspicuous spines at tips. Often bright red or orange. Aggressive predator. Prey includes frogs and other centipedes. Bite painful but not dangerous. Female cares for offspring. Throughout southern Africa.

Order Geophilomorpha

4 EARTH CENTIPEDES

Antennae short with 14 segments. Body long, worm-like. Legs shorter than body width. Last pair of legs long, similar-looking to antennae. No eyes. Head difficult to distinguish from rear. Moves backwards and forwards with equal speed and agility. Lives in burrows in loose soil and compost heaps. Feeds on earthworms. Digests food externally, sucking up liquid residue. Some species capable of producing light. Female cares for offspring. Moist soils throughout southern Africa.

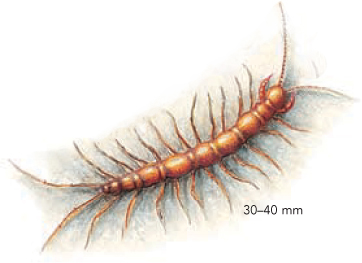

Order Lithobiomorpha

5 STONE CENTIPEDES

Antennae roughly one-third body length. Legs longer than body width. Body shiny, light to dark reddish-brown. 15 pairs of legs. Hides under stones, bark. Sheds legs to aid escape from predators; they regrow. Squirts sticky fluid from rear to trap predators such as ants, spiders, earwigs. Feeds on insects. Female does not care for offspring. Throughout southern Africa.

Similar

HOUSE CENTIPEDES Order Scutigeromorpha

Antennae longer than body. Legs long, delicate. Often trapped in baths and basins in houses.