THE 1919 TREATY OF VERSAILLES banned German military aviation, but secret agreements between Germany and the USSR in 1923 established clandestine facilities at Lipetsk, Russia. In the 1930s the Deutscher Luftsports Verband (German Air Sports Association, DLV) also trained future military aircrews at the deceptively misnamed ‘Zentrale der Verkehrs Fliegerschule’ (Central Commercial Pilots’ School). In February 1935, Hitler publicly announced the formation of the new Luftwaffe (‘air arm’). His longtime collaborator Hermann Göring, a charismatic but militarily limited ex-Great War fighter pilot, was given chief command with the rank of Reichsmarschall – a role for which he would later prove spectacularly ill-qualified. For both operational and economic reasons priority was given to the creation of a tactical air force suitable for close support of ground offensives during a short, aggressive war, with a ‘general purpose’ medium bomber fleet rather than long-range strategic bombers.

Late 1934: the 22-year-old Adolf Galland in the blue-grey uniform of a pilot-qualified Deutscher Luftsport Verband (DLV) Flieger; note the rhomboid-shaped collar patches with rank ‘Schwingen’, soon to be adopted by the Luftwaffe. Galland first came to prominence as a ground attack and fighter pilot with the Legion Condor in Spain where, by the fall of the Republic in March 1939, many of the Jagdflieger who would become household names in 1940 – e.g. Galland, Günther Lutzow, Werner Mölders and Walter Oesau – had already become aces, and in the process had developed the most up-to-date fighter tactics in the world. Regular rotation of personnel to Spain gave a large number of airmen of all branches invaluable combat and command experience denied to their early opponents in World War II. German airmen in Spain claimed 386 enemy aircraft shot down, for 232 aircraft and 226 men lost. (Private collection)

The purpose of this book is to detail and illustrate Luftwaffe uniforms, work clothing and flying kit, and there is no space here for even a summarised history of the events of Germany’s war in the air. (Readers are directed to the Osprey Aviation list, of which the most relevant titles are listed on the inside back cover of this book.) However, a brief list of the main campaigns may help put the uniform information and illustrations in context:

In July 1936 the Spanish Civil War broke out and, spurred by the prospect of Soviet support for the Republic, Hitler acceded to the Nationalist Gen. Franco’s appeal for aid. The German volunteer corps or ‘Legion Condor’ had a strong air element, and the war provided invaluable opportunities to test machines and tactics and to accustom personnel to combat. This practical ‘edge’ contributed greatly to German victories in the Blitzkrieg campaigns of 1939 and 1940 against Poland, Norway, Denmark, France and the Low Countries and British expeditionary air forces. Although suffering significant casualties, Luftwaffe ground attack and bomber units greatly assisted the rapid advances of armoured and motorised troops, and the Messerschmitt Bf109 fighter units achieved air supremacy.

In July–October 1940 daytime operations to destroy the Royal Air Force (the Battle of Britain) in preparation for an invasion came close to success, but finally failed with heavy loss. The Luftwaffe switched to night bombing of British cities, ports and industrial targets; this Blitz of November 1940–May 1941 caused great damage and some 85,000 civilian casualties but brought little military advantage.

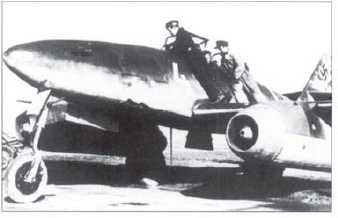

Perhaps the most potent symbol of the Luftwaffe’s supremacy in 1939–40: the Junkers Ju87B Sturzkampfflugzeug or ‘Stuka’. The single-engined precision dive-bomber was trialled in combat by the Legion Condor in Spain, and vindicated during the Blitzkrieg campaigns and in Russia and the Mediterranean in 1941. However, its conspicuous success depended upon the absence of opposition from modern fighters; in the Battle of Britain the much greater speed, manoeuvrability and armament of the Hurricane and Spitfire completely outclassed it. The Ju87 was later successfully converted into a ‘tank-buster’ with under-wing mounted 37mm cannon, and the former role of the Stukageschwadern was largely taken over by Schnell-Kampfgeschwadern and Schlachtgeschwadern equipped with modified single-seat fighters.

Even in peacetime, Junkers – which also built the Ju52 transport and Ju88 bomber – had five airframe factories, three more for complete aircraft, and a workforce of 25,000-plus. The secretive rebirth of the aircraft industry dictated wide dispersal of production and development facilities, and Germany’s 29 aircraft companies had 51 main complexes scattered across the country. While this would hamper Allied attempts to interrupt production by bombing, the gathering of components from separate factories for final assembly would further aggravate Germany’s increasingly critical fuel shortages.

In 1941 the successes of the Western Blitzkrieg were replicated on a smaller scale in the Balkans, Mediterranean and North Africa, mainly against the RAF and Royal Navy. From June 1941 the invasion of the USSR brought staggering early success; the Luftwaffe completely outclassed the Red Air Force in quality of equipment and aircrew skills, and vast numbers of Russian aircraft were destroyed. During 1942, however, the strain of fighting on three fronts simultaneously began to tell; Britain was no longer alone. The first USAAF daylight raids across the Channel began in August, and early losses did not deter a steadily increasing effort. During the summer a strengthened RAF Desert Air Force outnumbered Rommel’s air support in Africa, while his vital supply lines from Italy were ravaged. In Russia the Red Air Force, buying time by dogged sacrifice, was slowly increasing in numbers and capability. The turn of 1942–43 brought catastrophic defeat in Africa and at Stalingrad, costing many aircraft and experienced crews. The weakened Luftwaffe would have little serious effect on military operations in Italy in 1943–45.

In early 1943 Luftwaffe fighter units were already being pulled back from Russia and the Mediterranean to help defend Germany against the US 8th Air Force daylight offensive. This battle of attrition intensified, and from winter 1943/44 US escort fighters had the range to accompany the Flying Fortresses all the way to Berlin and back. The German bomber fleet had been ground away to almost nothing, and many bomber aircrew were retrained on other aircraft; the heavy fighter (‘destroyer’) squadrons were largely retrained as night fighters to counter the RAF’s massive night bombing campaign against German cities and factories.

An Fw190A-8 of 4 Staffel, II.(Sturm)/JG 4; the rear fuselage bands – here black and white – were for quick Geschwader identification of Reichs Defence Command aircraft. From May 1944 heavily armed and armoured Fw190A Sturmgruppen (assault groups) were formed in JG 3, 4 & 300; these pilots concentrated on the heavy bombers at all costs – even to the extent of ramming – while the more agile Bf109Gs were supposed to keep the escorts occupied. Though this distinction broke down in practice, the Sturmgruppen proved quite effective; but the concept later gave rise to volunteer ‘Rammjäger’, who vowed to fly directly into the bombers – a Wagnerian stupidity which achieved very few successes. By 1944 most Luftwaffe machines were ageing designs pushed to the limits of development with ‘bolt-on extras’. Even so, ten day fighter aces shot down 25 or more four-engined bombers, the equal top scorers being Oberst Walther Dahl and Major Georg-Peter Eder, each with 36 ‘heavies’. (Franz Selinger)

While dwindling Luftwaffe fighter and ground attack squadrons continued to support German armies fighting a long and bitter defensive battle on the Eastern Front, the Western Allies opened another front by landing in Normandy in June 1944. They enjoyed air superiority from the first, and in the battles above their rapidly advancing armies many irreplaceable Luftwaffe veterans were lost. German aircraft production actually increased toward the end of the war; but the shortage of experienced pilots, and of fuel, grew steadily more crippling as the Luftwaffe tried simultaneously to support retreating German armies in the West and East and to defend the Reich against the Allied bomber armadas. New weapons – such as the world’s first operational jet fighter, the Messerschmitt Me262 – proved too few, and far too late.

By 8 May 1945, over 97,000 members of the Luftwaffe were recorded as dead, missing or wounded. Many combat airmen fell into despair upon discovering the crimes that had been committed behind the shield of their courage. Like their Allied counterparts, the great majority had been driven by a desire to serve their country, and to experience the ultimate test of self, rather than by ideology. Most of the men who faced them in the skies regarded them with nothing but respect.

‘Blackies’, wearing dark and ‘raw grey’ work clothing, work on an Me262A-1A jet of Kommando Nowotny at Achmer in late September 1944. This evaluation unit would be absorbed in November into the only complete jet Jagdgeschwader as III./JG 7. The Me262 pilots put their great speed advantage (c.540mph) and four 30mm cannon to good use; the world’s first jet ‘ace’ was Leutnant Alfred Schreiber, and Oberstleutnant Heinz Bär achieved 16 ‘kills’ while flying the Me262 (Oberleutnant Kurt Welter of 10./NJG 11 claimed at least 20 jet night victories). Nevertheless, jets were shot down by Allied piston-engined fighters; and many were ‘ambushed’ during take-off and landing, despite special airfield protection flights of Fw190s. (Hans Obert)