Napoleon conceived a four-phase plan to resolve the crisis in Germany. Firstly, he would retain control of as much of Germany as he could with the forces immediately available. Secondly, using these forces he would buy time to allow his new army to assemble in France. Once this was achieved he would march at the head of this army to re-establish control over Germany. Finally, he would restore contact with his isolated fortress garrisons, regaining his position as master of Central Europe. Every success along the road would help persuade his now reluctant allies to toe the line.

The Prince of Sayn-Wittgenstein, Russian general and Allied commander in the spring of 1813. As with so many Russian officers, Wittgenstein was of German origins. His performance in the Spring Campaign was considered inadequate and Barclay de Tolly replaced him.

The Prusso-Russian forces aimed to buy enough time to allow Russian reinforcements to arrive and strengthen the Allies’ position. The hope was that this would also spark an uprising across Northern Germany, causing Napoleon further problems. Finally the time won would allow negotiations to take place with the Austrians. Persuading the forces of the Habsburg crown to join the new coalition would probably tip the scales decisively in the Allies’ favour. But to persuade the Emperor to join the struggle against Napoleon, the Prusso-Russian forces would have to show themselves capable of matching the French on the field of battle.

This campaign was fought largely in Poland and the eastern part of Germany. Three main rivers cross this area, running roughly north to south. These are, from east to west, the Vistula, the Oder and the Elbe. Four major fortresses controlled the line of the Vistula – Danzig, Graudenz, Thorn and Modlin. Of these, all but Graudenz were in French hands. The three key fortresses along the River Oder, Stettin, Küstrin and Glogau, were all in French hands. The line of the River Elbe was held by fortresses at Madgeburg, Wittenberg and Torgau. The French garrisoned the first two, the uncommitted Saxons the third. The French also held the fortress of Spandau, near Berlin. Posen, the city where Eugène de Beauharnais first attempted to form an army to halt the Russian advance, lay halfway between the Vistula and the Oder.

These rivers and their fortified crossing points were the only appreciable physical barriers across the North German Plain over which the armies marched. With most of the fortresses and crossings in their hands, the French clearly held an advantage. However, the population of Prussia was a seething mass of resentment with a strong desire to avenge the humiliations of 1806. It would take little to ignite a rebellion against the French. This presented a clear threat to the French lines of communication. It was far from certain how long the French would be able to maintain their hold on the river crossings and fortresses.

East Prussia was already in a state of open rebellion – against both its king and Napoleon. Poland, allied to the French and very sympathetic to the Bonapartist cause, was in a state of turmoil. The advance of Russian forces would extinguish that country’s independence for more than a century. Prussia, nominally an ally of France, was clearly awaiting an opportunity to switch sides. This would cut off the French-garrisoned fortresses and deny much of Eastern Germany to Napoleon. The Prussian province of Silesia, in the south-east of the kingdom, was a natural base of operations for a Russian advance into Central Germany, and it was to here the Prussians transferred their seat of government.

1. 12 February – Having situated his headquarters at Posen and attempted to hold the line of the Vistula, Eugène finds it impossible and is forced to withdraw to Frankfurt an der Oder. Some garrisons are left besieged on the Vistula.

2. 18 February – Eugène is joined at Frankfurt by St. Cyr, increasing strength to 30,000. With this more powerful force he attempts to hold the line of the Oder River.

3. 16 January – Rapp besieged at Danzig.

4. 4,500 men besieged at Thorn by Barclay, who has replaced Chichagov.

5. 5,000 men at Modlin.

6. 6 February – German garrison at Pillau capitulates to the Allies.

7. Realising the Oder line is not defensible, Eugène withdraws through Berlin. Some garrisons are left along the Oder.

8. 6 March – Eugène arrives in Wittenberg to defend the line of the Elbe.

9. 18 March – 8,500 man garrison of Stettin besieged. Hold out until 21 November 1813.

10. 5,000 men besieged at Küstrin (General Fornier d’Albe). Hold out until 7 April 1814.

11. 5,000 man garrison at Glogau.

12. c.18 February – Kutuzov’s and Miloradovich’s advance reaches Kalisch.

13. Reynier falls back before Kutuzov, through Glogau, Dresden and Leipzig.

14. 18 March – Wittgenstein advances and besieges Stettin with Yorck.

15. 18 March – Morand, having marched from Swedish Pomerania, finds Hamburg in Allied hands.

16. 2 April – Wittgenstein’s forward elements having pushed on to Lüneburg, defeat General Joseph Morand (who is mortally wounded).

17. Following Prussia’s entry into the war, Blücher advances from Silesia to Dresden.

18. Blücher is joined by Witzingerode’s Russians and they advance on Leipzig.

19. Eugène’s forces assemble, including Lauriston’s V Corps, elements of I and II Corps, and I and II Cavalry Corps. He moves to Leipzig, then withdraws further west.

20. Magdeburg garrisoned by 8,000 men.

21. Wittenberg garrisoned by 5,000 men.

22. 11 March – Wittgenstein’s advance reaches Berlin. 13 April – Wittgenstein besieges the French garrison of Spandau (General Bruny, 3,000 men), which capitulates on 24 April.

23. Wittgenstein, leaving a force to blockade Magdeburg, moves to unite with Blücher.

24. 5 April – Eugène, having advanced against Wittgenstein, is checked at Möckern. He then retires and Wittgenstein moves to unite with Blücher.

25. Bernadotte’s Swedish Army in Swedish Pomerania.

26. Sacken watches Poniatowski on the border of the Duchy of Warsaw and Galicia.

27. Poniatowski virtually interned in Austria.

28. Saxon garrison of Torgau (General Thielemann) of uncertain loyalty.

29. Allied raiding-parties active in advance of their main bodies during this period.

On 17 January 1813, Napoleon placed his troops in Germany under the command of Viceroy Eugène de Beauharnais. Eugène did his best to rally the scattered remains of the Grande Armée of 1812 in the Polish town of Posen. He had at his disposal 4,000 men in each of the fortresses of Modlin and Zamosc. In Danzig (Gdansk), he had 30,000 men and in Thorn (Torun) 4,500. His only reserve was the Division Lagrange together with Division Grenier, the latter on its way from Italy. These forces numbered a further 28,000 men.

General Barclay de Tolly. A Russian general of Scottish origins, he succeeded Wittgenstein as Allied commander after the Battle of Bautzen. By then, it was too late for him to play a significant role in the outcome of the campaign.

Prince Kutusov. Seen as the liberator of the Motherland in 1812, he was reluctant to see the Russian Army get involved in the struggle for Central Europe. This reluctance hindered the Russian advance into Germany and allowed Napoleon time to rebuild his forces. Had Kutusov acted more decisively, Napoleon may well have lost control of all of Germany before he had raised a new army.

Facing them were 11,000 Russians from Wittgenstein’s forces who were advancing into Germany. Other forces moved to cut off the fortresses of Danzig and Thorn, breaching the first line of defence, along the Vistula River. The fortress of Pillau on the Baltic coast of East Prussia capitulated to the Allies on 6 February.

Misgivings over Austrian intentions led to a pause in the Russian advance. The movements of Field Marshal Prince Schwarzenberg’s Corps, the Austrian contingent in the Grande Armée of 1812, across Poland had caused consternation. Austria, Russia and Prussia had partitioned Poland among themselves at the end of the 18th century, and all had territorial claims in the Polish state re-instituted by Napoleon. Schwarzenberg’s men placed the Austrian statesman Metternich in a good position to play a role in mediating a peace in Europe. As Napoleon’s forces had been crushed in Russia, the Prussian state virtually bankrupted by the French occupation and Russia’s armed forces reduced to a pale shadow by the Campaign of 1812, the one sizeable force still intact was Schwarzenberg’s. However, Austria felt that it would be better policy to extract his Corps from the chaos left in the wake of Napoleon’s retreat.

Technically, the Austrians were still allies of Napoleon and at war with Russia, so negotiations for a cease-fire with the Russians commenced on 6 January. A few days later, the Russian advance into Poland recommenced. Not wanting to be seen to breach their alliance with Napoleon, the Austrians arranged for the Russian forces to move in such a way that Schwarzenberg was left with no choice but to withdraw. The Austrians evacuated Warsaw by 6 February, moving south. This made the position of Reynier’s Saxon Corps untenable. Until then, the Saxons had been co-operating with the Austrians. Reynier fought his was back to Kalisch, south-west of Warsaw. On 25 February, the Austrians and Russians signed a cease-fire. The Russian westward advance could now continue unopposed.

The remains of four corps of the Grande Armée had been sent to garrison various fortresses, leaving Lagrange’s Division, which had not yet reached Posen, Eugène’s headquarters, for use in the field. Poniatowski’s and Reynier’s Corps had been checked by Russian moves, so all that was available in Posen were the remnants of the Guard, VI, VIII and IX Corps. Small numbers of reinforcements were moving to join Eugène. From the troops at his disposal Eugène formed four weak divisions under Roguet, Rechberg, Gérard and Girard. When Grenier’s Division arrived from Italy at the end of January, it was divided in two and used to form a new XI Corps under Marshal St. Cyr.

The reports coming in of Prussian and Russian activity caused Eugène concern about his ability to hold a position so far forward. The uprising in East Prussia led by Yorck was one danger. Another came from the Russians, who had now negotiated a cease-fire with the Austrians. Then, on 3 February, the King of Prussia called for volunteers to join his army and moved his government from Berlin to Breslau. In Silesia he would be beyond the reach of French interference. Here was a signal if it were needed that Prussia was about to rise against Napoleon, threatening Eugène’s line of communications. Russian raiding parties already hitting the French lines of communication deep inside Prussia further exacerbated Eugène’s already precarious situation. On 12 February, the Viceroy started a withdrawal to Frankfort an der Oder, the bulk of his troops arriving there on 20 February. He was harrassed every step of the way by Cossack raiders.

General der Kavallerie Blücher. The symbol of anti-Bonapartism in Germany, Blücher was highly popular with his men. While he led from the front his chief-of-staff commanded the army, forming the dual leadership that came to characterise Prussian and later German armies.

Once Eugène had crossed the Oder River, his position improved significantly. With the additional manpower now available to him, he would be able to hold the bridgeheads across the Oder and turn it into a significant barrier. He now had about 50,000 men and 94 guns at his disposal. His right wing, the 9,000 men and 32 guns of Reynier’s Corps, was stationed at Glogau, along with some Polish contingents. Rechberg’s Bavarian Division was at Krossen – 2,300 men with 12 guns. Stationed along a line between Frankfort an der Oder and Küstrin were Roguet’s, Girard’s and Gerard’s Divisions from Posen and Grenier’s and Charpentier’s Divisions (formed from Grenier’s Division), a total of 35,000 men and 46 guns. A weak detachment of about 4,000 men and four guns, formed from the remains of I Corps and parts of the garrison of Stettin, held Schwedt. To their rear, forming the second line around Berlin, was Lagrange’s Division, just reinforced to almost 14,000 men and 40 guns. A detachment of 3,000 men and 17 guns under General Morand was in Swedish Pomerania. In addition to these men were the increasing numbers of stragglers from Russia rejoining the army. At this time, 4,000 were in Glogau, 2,800 in Küstrin, 4,400 in Stettin and 1,300 in Spandau. Finally, there were about 7,000 wounded in Berlin and Frankfort an der Oder but their potential combat value was negligible.

Napoleon’s new army was beginning to assemble on the Elbe. By the middle of March, he had 22,400 men with 34 guns forming the Corps of Observation of the Elbe. It later became V Corps under Lauriston. He had an additional 1,900 men in Erfurt. All were poorly trained and equipped however and could not be expected to support Eugène for some time. In this light Eugène decided to take a defensive stance along the Oder line, rather than the offensive posture Napoleon wished.

King Frederick William of Prussia left Berlin for Breslau on 22 January. A French garrison occupied the fortress of Spandau near Berlin and more of Napoleon’s troops were moving into the Mark of Brandenburg, the Prussian province around Berlin. To contemplate going to war with an enemy occupying a substantial part of one’s own territory is a risky business and Frederick William needed certain very clear assurances from the Russians before doing so. The negotiations with the Czar’s representatives reached a conclusion with the signing of a treaty of alliance on 27 February. Prussia could now begin the preparations for war in earnest.

Meanwhile, Cossack raiding-parties under Czernichev, Tettenborn and Benckendorff crossed the River Oder near Küstrin and spread terror throughout the French-occupied areas. By 20 February, Czernichev and Tettenborn reached Berlin, where they demanded its surrender by its French commandant Augereau. Although the garrison chased off the Cossacks, the effect on morale was significant, striking fear into the French and encouraging the Prussians to stage an uprising.

A French Général de Division and his adjutant. The division was the standard grand tactical unit in the French Army of this period. Napoleon was fortunate to have a number of highly experienced and most capable men to fill this post. Watercoloured lithograph by Bellangé.

Concerned that his forces may become trapped in the Oder fortresses, Eugène now decided to abandon the line of the river. Before doing so, he blew up the bridges and removed all shipping. Two natural defence lines across this part of the North German Plain had now been abandoned to the Russians. Leaving Gérard for the time being in Frankfort an der Oder with 3,000 men and 8 guns, Eugène marched with Roguet’s Division from Frankfort an der Oder via Fürstenwalde to Köpenick, reaching the outskirts of Berlin on 22 February. Girard’s Division marched via Müncheberg and Fürstenwalde, as did Grenier and Charpentier, joining Eugène at Köpenick. The detachment at Schwedt was ordered to Stettin. In response to Augereau’s urgent appeals for assistance, the Guard Cavalry, about 1,000 sabres, was sent off first. By the beginning of March, the French had concentrated about 29,000 men around Berlin.

Rechberg’s Bavarians, now under Reynier’s orders, fell back to Kalau via Guben and Cottbus. Reynier abandoned Glogau on 22 February, marching via Sprottau, Sagan and Rothenburg and reaching Bautzen on 1 March. From here he was ordered to fall back to Dresden and secure this important Elbe crossing.

The Russians had meanwhile halted their advance, partly as a result of the general exhaustion of their troops and partly due to delays in concluding the alliance with Prussia. At the beginning of March their advance resumed. Three raiding parties totalling 8,500 men and 24 guns moved on Berlin. This was enough to convince Eugène that he could no longer hold this city. Painfully aware of the implications of abandoning Berlin, he moved via Trebbin and Beelitz, crossing the Elbe at Wittenberg on 7 March before setting up his headquarters in Leipzig on 9 March. Gérard fell back from Frankfort an der Oder to Jüterbog, with Rechberg retreating from Kalau to Meissen, while Reynier marched to Dresden. Morand fell back from Swedish Pomerania towards Hamburg only to find that its commander had left the city fearing an uprising by the inhabitants. Tettenborn’s Cossacks entered the city on 18 March to the joy of its residents. Three successive defence lines had now fallen to the Russians and Napoleon’s hold on Germany was seriously threatened.

With 36,500 men and 98 guns, Eugène had bought enough time for further French formations to assemble. Added to his resources now were Lauriston’s V Corps with 30,000 men and 34 guns, 1st Division (Philippon) of I Corps with 11,000 men and 16 guns, 1st Division (Dubreton) of II Corps with 8,500 men, Latour-Maubourg’s 1st Cavalry Corps with 1,300 sabres and Sébastiani’s 2nd Cavalry Corps with a further 1,800 sabres.

Eugène now had about 90,000 men and 148 guns at his disposal. He also had the garrisons of Madgeburg (8,000 men) and Wittenberg (5,000 men) available. The loyalties of the Saxon garrison of Torgau under General von Thielemann remained uncertain. Eugène did not have sufficient men to cover the entire line of the Elbe. However, Hamburg, at the mouth of the Elbe and part of metropolitan France, could not be abandoned and the restless Saxons, further down the Elbe, could not be left to their own devices. The Viceroy placed Marshal Davoût, commander of I Corps, in and around Dresden with 19,000 men and 60 guns. These included one brigade from Philippon’s Division, the remains of Reynier’s VI Corps and Gérard’s Division from XI Corps. On 19 March, Davoût blew out part of the bridge across the Elbe. Eugène himself with the remainder of XI Corps and the 1st Cavalry Corps (19,000 men and 22 guns) would cover from Dresden and Torgau to the Saale River. From Philippon’s Division 6,700 men and 16 guns and a further 8,000 men from Dubreton’s Division held Wittenberg and Kemberg, while V Corps and 2nd Cavalry Corps (33,000 men and 42 guns) constituting the left wing, covered the area around Madgeburg from the Saale to the Havel. Eugène had only 6,000 men on the Lower Elbe under Morand and Carra St. Cyr. The remainder had deserted. His Grand Headquarters would be in Leipzig, with the 4,000 men and 8 guns of Roguet’s Guards Division.

French lancer. Due to the heavy losses of both manpower and horsepower in Russia in 1812, the numbers of cavalrymen available to Napoleon was much too low for his purposes. Lacking sufficient cavalry, he was able to win battles but was not able to destroy his enemy’s forces on the retreat with a vigorous pursuit.

The Treaty of Kalisch was signed on 28 February, but the delay in reaching this agreement had cost the Allies precious time and they now needed to regain the initiative. The Prussian General von Scharnhorst pleaded in favour of a rapid advance against Eugène with all available forces, but failed to win over the Russians. Prince Kutusov saw the objectives of the Russian Army achieved with the expulsion of the invader from Russian soil. More precious time was lost as the Allies debated a course of action. Finally, it was agreed that the troops in the northern theatre including the 27,000 Prussians and 120 guns under Yorck, Bülow and Borstell should be placed under Wittgenstein’s command. In the southern theatre, 27,600 Prussians with 84 guns were placed under the commander of General der Kavallerie von Blücher, as was the 13,000-man-strong Russian corps under Wintzingerode. The Main Army consisted of the 33,000 men of two Russian corps under Tormassov and Miloradovich. All of these forces were to be commanded by Prince Kutusov. The plan was for Wittgenstein to move from Driesen to Berlin, to arrive there around 10 March, while Blücher would move on Dresden with the Main Army following him at a distance of three days’ march. The raiding parties from Wittgenstein’s Corps, consisting of about 5,000 sabres, were to operate on the Lower Elbe, while a small Prussian detachment under Tauentzien besieged Stettin and another under General von Schuler invested Glogau. A detachment of Russians under Vorontzov was to blockade Küstrin. The main axis of advance would thus be along the Upper Elbe. It was hoped that by conquering Saxony the Allies would be able to persuade Bavaria to quit its alliance with France.

Wittgenstein entered Berlin on 11 March and set about besieging Spandau. On 17 March as Cossacks clashed with the garrison of Dresden and Blücher’s men advanced from Silesia, the King of Prussia founded the Landwehr (militia). Meanwhile, Sacken’s Corps invested the fortress of Czestochowa garrisoned by Poniatowski’s 12,000 men. It fell on 7 April and Poniatowski retired to Cracow, where he was disarmed and allowed to take his men to Saxony. Sacken’s men could now join the main field army.

Reacting to events, Napoleon ordered Eugène to concentrate his forces, now about 82,000 infantry, and 5,000 cavalry with 148 guns, on the Lower Elbe and take the offensive. The fall of Hamburg had been the signal for similar popular uprisings in Lüneburg, Harburg, Buxtehude and Stade. This area had been incorporated into France and constituted the 32nd Military Division, so its loss was unacceptable. Napoleon ordered Général Vandamme to move his men from Wesel on the Rhine to Bremen, from where, supported by Morand and Carra St. Cyr, he quelled the uprisings and beat off the Russian raiding-parties.

Foot artillery and train of the Imperial Guard. Famed for their heavy 12-pdrs, Napoleon’s Guard Artillery often formed the core of the grand batteries that were characteristic of a number of his battles. Lacking trained infantrymen in 1813, Napoleon came to rely more on his artillery to beat his enemy. (Bellangé)

On 28 March, Napoleon placed Davoût in command of this sector of the front, held by parts of I and II Corps. Davoût moved to Lüneburg, which Dörnberg and Czernichev were using as a base for their partisan operations. The partisan leaders avoided a battle with Davoût but continued their operations. On 21 April, overall command of the Allied operations in this theatre was given to General Count Wallmoden. His forces numbered 10,000 men. By 27 April, the French had assembled a force of 40,000 men to move on Hamburg; an indication of the effectiveness of the Allied operations here and the extent of the popular uprising.

Meanwhile, Eugène moved his headquarters from Leipzig northwards to Madgeburg, joining Lauriston and Sébastiani. More of the French Army moved here to join him. By the end of March, V Corps (4 divisions, 30,500 men with 66 guns) was covering the Elbe from Kalbe to Stendal while Sébastiani’s Cavalry Corps (2,000 sabres plus 400 to 500 mounted Gendarmes) was deployed above and below Madgeburg. Part of Division Philippon of II Corps (6,700 men, 8 guns) came up from the fortress of Erfurt while Roguet’s Guards Division was sent from Leipzig (3,200 men with 14 guns) and Latour-Maubourg’s Cavalry Corps came up from Wittenberg (2,500 sabres with 6 guns). Some of Davoût’s men (Brigade Pouchelon of I Corps – 4,300 men, and Gérard’s Division – 6,200 men with 16 guns) arrived from Dresden. Later, once relieved by Victor, XI Corps (18,000 men with 30 guns) joined him.

After careful preparations, Eugène moved three divisions of Lauriston’s Corps across the Elbe towards Möckern on 23 March, but rumours of Allied plans to advance towards Hanover via Havelberg caused him to retrace his steps on 26 March. However, by the beginning of April, Eugène had sufficient men available to oppose any advance from Berlin by Wittgenstein; something he was to attempt a few days later at Möckern.

Wittgenstein had been in Berlin since 11 March and Yorck had arrived there on 17 March. Borstell joined them shortly afterwards. Bülow waited at Stettin until Tauentzien assembled his reserve and garrison battalions before moving on to Berlin, where he arrived on 31 March. Blücher’s forces, on the Allied left, moved on Dresden. Kutusov remained in Kalisch in Silesia.

On 20 March, a council of war in Kalisch agreed that it was no longer possible to destroy Eugène’s forces before Napoleon arrived. It was therefore decided to unite Wittgenstein’s and Blücher’s forces and hold a position along a line from Leipzig to Altenburg where they would await Napoleon’s advance. Eugène was to be watched and a confrontation avoided until the union of Wittgenstein and Blücher was completed. Yorck’s Corps was to move to Meissen. Bülow, supported by Borstell, was to cover the line from Madgeburg to Wittenberg. Blücher and Wintzingerode were to cross the Elbe at Dresden. The partisan warfare on the Lower Elbe would continue and the uprising in Hamburg would be supported.

As Kutusov remained in Kalisch until 7 April, when the King of Prussia persuaded him to move, Blücher at first lacked support. Wittgenstein received his orders on 24 March. Deducting the raiding-parties under Czernichev, Dörnberg and Benckendorf and the corps under Helfreich observing Spandau, he had 27,000 men, 3,500 Cossacks and 152 guns available. This force was divided into three corps under Berg (Russian), Yorck and Borstell (Prussians). Eugène’s movements caused Wittgenstein to hesitate, and he awaited the arrival of Bülow’s 7,000 men and 26 guns on 26 March before moving off. Hearing that Blücher’s march to Altenburg was unopposed, Wittgenstein made directly for Wittenberg. By the end of March Kleist, formerly Yorck’s vanguard, was at Marzahna with 5,400 men, 400 Cossacks and 26 guns. Yorck himself was at Belzig with 9,000 men and 44 guns and Berg at Brück with 8,000 men, 250 Cossacks and 62 guns. Bülow, having detached Thümen’s Brigade to cover Spandau, was at Nedlitz, directly east of Madgeburg, with 3,800 men, 650 Cossacks and 12 guns.

On 31 March, after a disagreement with Scharnhorst, who favoured adopting a more defensive approach, Wittgenstein decided move on Hanover via Brunswick and to fight Eugène if he should stand at Madgeburg. He would first cross the Elbe at Rosslau and unite with Blücher in the direction of Leipzig. On 2 April, Yorck moved on Senst, Berg on Belzig, and Kleist was ordered to take Wittenberg should Eugène abandon it.

Horse artilleryman of the Imperial Guard. The gunners of the horse artillery were normally all mounted, allowing this arm to accompany the cavalry, giving it close-range artillery support. (Bellangé)

French line infantry. The smart blue uniforms with their brightly coloured facings that fill the paintings of late-19th century romantic artists were probably a rare sight in 1813. It is more probable that the average ‘Marie-Louise’ merely wore a greatcoat over his civilian clothes and a soft cap on his head rather than the bulky and more expensive shako. (Richard Knötel)

Before these actions could be executed, Eugène crossed the Elbe at Napoleon’s urging, taking 50,000 men – Roguet’s Guards, V and XI Corps and Latour-Maubourg’s cavalry – and 116 guns with him. Assembling at Madgeburg-Neustadt on 1 April, Eugène moved the next day with V Corps advancing against Borstell’s vanguard at Königsborn, pushing it back to Nedlitz. The next day, XI Corps and Latour-Maubourg crossed the Elbe, forcing Borstell’s main body back from Möckern. Bülow was in the town of Brandenburg on 3 April and force-marched his men to aid Borstell. Receiving Borstell’s reports, on 2 April Wittgenstein also decided to march to support him, assembling his forces at Senst and Belzig the next day. Believing Eugène intended to march on Berlin, he ordered Borstell and Bülow to withdraw slowly on Görzke and Ziesar while he attacked the French flank. Receiving his orders during the night of 3/4 April, Borstell withdrew from Möckern in the morning, halting at Gloina and Gross-Lübars.

Eugène halted at Möckern, Gommern and Dannigkow, missing the opportunity to crush Borstell. Wittgenstein reached Zerbst on the evening of 4 April and planned to attack the French the next day, although he estimated Eugène to have 40,000 men. With only 23,000 men, 500 Cossacks and 130 guns himself, he delayed his assault to 6 April, using Borstell and Bülow to keep Eugéne’s attention. He then planned to use these same forces to pin Eugène on the road from Möckern while Berg and Yorck drove into his right flank. Wittgenstein received a report, false as events proved, that Eugène was withdrawing and decided to attack immediately.

Général Jacques-Alexandre-Bernard Law Lauriston, (1768-1824). Son of a French general and a graduate of the École Militaire in Paris, Lauriston rose through the ranks during the Revolutionary Wars, being made a general in 1805. A veteran of several campaigns, Lauriston was a highly experienced and most capable divisional commander.

Marshal Auguste-Frédéric-Louis Viesse de Marmont, Duke of Ragusa, (1774-1852). The twenty-third of Napoleon’s marshals to be appointed, Marmont suffered a defeat at the hands of the Duke of Wellington at Salamanca in July 1812. Severely wounded there, he returned to France to recover before being recalled by Napoleon to participate in the campaigns of 1813 in Germany. Commanding VI Corps under the Emperor’s watchful eye, Marmont performed well.

Wittgenstein thus found himself muddling his way into a battle before having fully concentrated his forces. Eugène enjoyed the benefit of fighting from a central position against forces disadvantaged by being spread out over a relatively large area

On Eugène’s right flank Division Lagrange of V Corps (9,500 men, 16 guns) was at Wahliz with their vanguard and the 1st Light Cavalry Division at Gommern and Dannigkow. His main body consisted of the 24,000 men and 46 guns of XI Corps in three divisions at Karith, Nedlitz and Büden. The 3rd Light Cavalry Division was at Zeddenick with 800 horses and 6 guns. 1st Cavalry Corps was deployed to the front of Eugène’s right and centre covering the Ehle River, which ran through marshy terrain difficult for an attacker to cross. His left flank was held by Maison’s Division, also of V Corps. This consisted of 5,000 men and 18 guns at Woltersdorf. In reserve behind XI Corps he had Rochambeau’s Division of 8,000 men and 16 guns. In addition Roguet’s Guards Division (3,200 men, 14 guns) was at Pechau holding the Klus causeway, an important road through the marshes around Madgeburg.

Hünerbein, in command of Yorck’s vangaurd, advanced towards Dannigkow, making contact with the French at noon when Lagrange’s vanguard fell back to Dannigkow. Meanwhile, a small Prussian detachment moved via Dornburg towards Gommern, but reinforced by troops moving up from Gommern, the French managed to hold on until Hünerbein’s men eventually took the village at bayonet-point.

Yorck’s main body, accompanied by Wittgenstein, reached Leitzkau by 4.00p.m. On hearing the sounds of cannon-fire, he rushed forward to support Hünerbein. Some of the artillery saw action, but the French prevented the Prussians from making any significant advances.

Berg’s vanguard, commanded by Roth, also came into action at 4.00p.m. on Yorck’s right at Vehlitz. The marshy terrain restricted the movement of the two Prussian columns and the Allied assault did not begin until 6.00p.m. when Borstell’s infantry arrived, having marched from Gloina. The three columns now launched a successful attack. Despite heavy losses the Italians of Brigade Zucchi of XI Corps held on until nightfall, although the provisional corps commander, Général Grenier, was severely wounded. With night falling the Allies did not pursue.

Oppen, commanding Bülow’s vanguard, having the furthest to march, reached the area of Möckern about 4.00p.m. While Bülow’s infantry and artillery occupied Zeddenick, Oppen’s cavalry drove back the 1st Light Cavalry Division to Vehlitz, where Borstell’s men finished them off. The French troops at Nedlitz fell back as well. After dark Bülow retired to Zeddenick.

Although Eugène had the advantage of internal lines of communication and superior numbers, the Allies had proved victorious. Their losses amounted to 500 men with the French losing around 2,200 men and one gun. However, the marshy terrain had restricted Eugène’s movements as much as his opponents’ and his men had acquitted themselves well. The Allied success can be put down in part to luck – had Wittgenstein not been misinformed about Eugène’s intentions, then he may well not have attacked – and partly to the bold decision to attack a superior force. That night, Eugène fell back to Madgeburg, crossing to the west bank of the Elbe the next day. All the river crossings were destroyed, as was the Klus causeway, and Eugène abandoned any thoughts of an advance on Berlin. The first battle of the campaign had been an Allied victory – there were firm hopes this presaged greater success.

Marshal Étienne-Jacques-Joseph Alexandre Macdonald, Duke of Tarentum (1765-1840). Awarded his marshal’s baton for his performance at the Battle of Wagram in 1809, Macdonald commanded a corps in the Russian campaign of 1812 and the German Campaigns of 1813.

As Eugène had apparently abandoned any intentions of advancing on Berlin, Wittgenstein began preparations to cross the Elbe himself. Wittenberg was now cut off with a screen of Cossacks to its west and invested by Kleist, while Bülow and Borstell took up positions around Madgeburg. These siege operations reduced the forces available to Wittgenstein – with reinforcements, Berg and Yorck together now numbered 18,000 men, 700 Cossacks and 92 guns. Furthermore, the Elbe crossing at Rosslau was precariously situated between two French-occupied fortresses at Madgeburg and Wittenberg, which limited its usefulness. Wittgenstein decided to await reinforcements before making his next major move. On 17 April he did try to take Wittenberg by surprise, but his assault columns were driven off. This fortress was then left under observation by a small force under the Russian General von Harpe.

On 23 April, Voronzow’s Corps replaced Bülow, arriving from Küstrin where it was replaced by Kapzevitch’s Division. On 25 April, Bülow’s 4,800 men, 400 Cossacks and 20 guns reached Dessau. Once there he was ordered to cover the bridgehead at Rosslau and place outposts in Aken and Köthen. Kleist now moved forwards marching to Halle while Helfreich joined Berg at Landsberg. Wittgenstein now had 22,000 men, 2,250 Cossacks and 143 guns. Spandau capitulated on 24 April, allowing the 3,000 men of Thümen’s command to join them. By the end of April Wittgenstein had his headquarters in Leipzig along with Berg’s Corps. Yorck, Kleist and Bülow were all nearby at Schkeuditz, Halle and Köthen respectively.

Meanwhile, Eugène had completed his withdrawal across the Elbe. News arrived of Morand’s defeat at Hamburg at around the same time as the bridgehead at Rosslau was established. Eugène now feared being shut up in Madgeburg and cut off from his lines of communication to the fortress of Wesel on the Rhine and the River Main to the south. He wheeled south and took up a new position, securing his flanks on the Harz Mountains and Elbe. From there, Eugène would be able to concentrate his army quickly and threatened the right flank of the Allies while leaving himself the option of a further withdrawal. He reinforced the garrison of Madgeburg with parts of the Divisions of Philippon and Dubreton, bringing it up to about 10,000 men. The remainder of Philippon’s Division took up positions to the north of the city, while Victor covered its south along the lower Saale with the rest of Dubreton’s Division and some cavalry. Eugène positioned Roguet’s Guards Division, V and XI Corps (Gérard replaced the wounded provisional commander Grenier, pending Macdonald’s arrival) and Latour-Maubourg’s Cavalry Corps – 50,000 men and 141 guns – roughly along the line of the Wipper River, facing south.

Marshal Nicolas-Charles Oudinot, Duke of Reggio (1767-1847). Appointed to the rank of marshal in 1809, Oudinot was twice wounded in Russia in 1812. He recovered sufficiently to command a corps again in 1813.

By mid-March, Blücher’s raiding parties had crossed the Elbe both above and below Dresden and his vanguard, Wintzingerode’s Corps, reached Bautzen on 20 March. Meanwhile, Durutte had completed his withdrawal from Dresden, so that when Wintzingerode entered the Saxon capital on 27 March he found it abandoned by the French. He erected a pontoon bridge and continued his advance, reaching Leipzig by 3 April. His raiding parties crossed the Saale at various points on 8 April and Lanskoi covered them by occupying Merseburg.

Blücher himslef advanced from Breslau (Wroclaw) in Silesia on 16 March and was in Dresden by the end of the month. Fearing a French move from the direction of Erfurt or Hof, he moved south towards Chemnitz. By 4 April, he had reached the upper Mulde at Zwickau and Penig, where he remained for the time being. As Saxony had not joined the Allies and her king had departed for Regensburg, leaving his government in the hands of commissioners, his domain was treated as enemy territory. Despite calls to join the Allied cause, the populace as a whole showed little enthusiasm.

The general indecision in the Allied high command again led to inactivity. Blücher’s three Prussian brigades took up positions in Penig, Zwickau and Nossen, the Reserve Cavalry at Kohren. Scouting parties were sent out to observe French movements and to link up with Wintzingerode’s partisans with patrols spreading throughout the province of Thuringia.

These patrols brought back unpleasant news. Napoleon was said to have arrived in Thuringia, concentrating his main army around Erfurt and moving to join Eugène. The Allies reacted by drawing their forces together. Wintzingerode was ordered close up on Blücher. By the evening of 25 April, he was approaching Borna, with his cavalry at Merseburg, Lützen and Weissenfels. Blücher had concentrated his forces at Borna, Altenburg and Mittweida.

Josef Anton, Prince Poniatowski, (1763-1813). A Polish patriot and member of the royal house, Poniatowski’s forces were unable to participate in the Spring Campaign of 1813.

At last, the main Allied army began to advance, albeit at a snail’s pace. Miloradovich’s Corps had left Glogau in Silesia on 9 April, but did not reach Dresden until 22 April, from where it was ordered to Chemnitz, where it arrived on 26 April. Tormassov’s Corps, which had left Kalisch on 6 April, reaching Dresden on the 24th. One of its divisions, that under Prince Gorchakov, was sent on to Meissen. By the time Napoleon was ready to cross the Saale, the Allies had assembled about 100,000 men. Bülow was at Dessau with 5,000 men, 400 Cossacks and 20 guns. Wittgenstein had a further 22,000 men with 2,200 Cossacks and 143 guns around Halle, Zörbig and Landsberg. The 37,000 men of Blücher’s command along with 3,500 Cossacks and 156 guns were deployed in a line Leipzig–Borna–Altenburg and at Mittweida. The main Allied filed army was deployed around Dresden and Chemnitz with 29,000 men, 3,000 Cossacks and 266 guns.

Russian Jäger. Supposedly a light infantry formation, by this stage of the Napoleonic Wars the distinction between line and light troops had become blurred. Nevertheless, Russian Jäger were considered to be a crack force. (Richard Knötel)

Frederick August, King of Saxony. Forced into an unwilling alliance with Prussia in 1806, Frederick August soon became an ally of Napoleon, receiving his royal crown as a reward. He sat on the fence at the beginning of 1813 before deciding for Napoleon. Napoleon’s defeat at Leipzig would cost him half his kingdom.

Napoleon left St. Cloud to join his army on the night of 15/16 April. Two days later, he reached Mainz, where he met Berthier at Headquarters with the Imperial Guard. Events had forced the Emperor to leave Paris earlier than he had intended. Eugène’s retreat across the Saale, the crossing of the Elbe by the Allies, the uprising in Hamburg, concerns about the actions of Austria and Saxony, the Prussian re-armament and the approach of Russian reinforcements forced Napoleon to react. He did so with fewer forces to hand than he had hoped.

Napoleon spent the next two weeks doing his best to accelerate the mobilisation of his forces. He lacked everything, particularly officers, artillery pieces and horses. However, by the end of April, he had assembled 228,000 men and 460 guns. Taking away the 48,000 men and 140 guns under Eugène’s command, Napoleon had the Imperial Guard, the Corps of Ney, Bertrand, Marmont and Oudinot, and the Cavalry Corps of Latour-Maubourg at his disposal. They amounted to 130,000 men with 320 guns. Eugène’s forces were designated the ‘Army of the Elbe’, while Napoleon’s was known as the ‘Army of the Main’. The Emperor intended to link his forces with those of Eugène and he marched from south-west Germany on Naumburg. The hilly terrain of Thuringia would help limit the effect of the Allies’ superiority in cavalry. From here he could also move on Leipzig and thus threaten both Berlin and Dresden. He could expect Berlin, the Prussian capital, to be defended and Dresden was on the Russian line of retreat to Silesia. By threatening both cities he hoped to force the Allies to divide their forces. He also hoped that by operating close to the Austrian border and in Saxony, he could bring these waverers over to his side.

Viceroy Eugène de Beauharnais (1781-1824). Son of Josephine, Napoleon’s first wife, Eugène was left holding Germany while Napoleon assembled a new army. He conducted this difficult task with some skill, being forced to abandon Berlin but holding the line of the River Elbe.

For the advance Ney’s Corps, the vanguard, was allocated the road running from Würzburg via Meiningen, Erfurt and Weimar to Naumburg. The Guard and Marmont were to march from Hanau via Fulda to Eisenach, before following Ney. Bertrand’s Corps, on its way from Italy, was to march via Bamberg and Koburg to Saalfeld.

When Napoleon arrived in Erfurt on 25 April to take command of his army, the leading elements of Ney’s Corps were in a line running from Auerstadt via Dornburg to Jena. The vanguard of the Imperial Guard was at Weimar with its main body in Erfurt. Bertrand was between Saalfeld and Sonneberg, his division of Württembergers under Franquemont at Hildburghausen. In Napoleon’s second line was Marmont around Eisenach and Langensalza. Oudinot’s newly formed Corps with the Divisions of Pacthod and Lorencez (transferred from Bertrand’s Corps) was at Bamberg and Nuremberg (Nürnberg), and Raglovich’s Bavarian Division at Bayreuth and Müncheberg.

Eugène was ordered to move towards the Saale, closing up on Ney’s left and holding the crossings at Wettin, Halle and Merseburg. However, by 25 April only Division Fressinet had moved. Napoleon had not achieved his objective of reaching the line of the Saale by 25 April. On arriving at Erfurt he found his forces ill-prepared to take the offensive and spent the next four days doing what he could to alleviate their problems.

By the evening of 30 April Napoleon’s forces had closed up to the Saale with Ney’s forces beyond Weissenfels. Eugène was to the north around Halle and Merseburg. A number of minor actions had been fought including one at Wettin on the Saale on 27 April where the Prussians withdrew without loss after blowing up the bridge. The next day at Halle Lauriston fought Kleist for several hours before the French withdrew. Once Merseburg and Weissenfels had fallen, the Prussians evacuated Halle. Napoleon’s offensive had started well and the performance of his ‘Marie-Louises’ pleased him particularly. He had now linked up with Eugène. Napoleon pressed on, hoping to catch the Allies before they had fully assembled their forces and crush them.

Russian line infantry. It was the Russian line infantry that formed the backbone of the Allied war effort at the beginning of 1813. Having suffered almost as much as Napoleon’s forces, the weakened battalions that marched into Germany at the beginning of 1813 were hardy veterans indeed. (Richard Knötel)

When Kutusov took to his deathbed on 18 April, a power vacuum was left in the Allied supreme command. Napoleon’s arrival in Germany made it clear that the Allies now had two choices; either to be pushed back by a French advance or to go over to the offensive themselves against a numerically stronger enemy, but one that lacked sufficient cavalry and whose infantry was of comparatively poor quality. It was decided to attack and the Allied forces began to concentrate around Altenburg with the aim of attacking the French right flank.

On Kutusov’s death on 28 April, Wittgenstein was appointed his successor. At 44 years old, he was a relatively young man for his position and reacted quickly. He was perceptive enough to appreciate that Napoleon’s initial objective was the line of the Elbe, so he decided to strike before Napoleon got there. This strategy was risky for if he were defeated Napoleon would be in a position to cut his line of retreat through Dresden. Communications with Silesia would be cut and the Allies would be driven away from Austria and a potential ally. Nevertheless the plan was to attack the French flank as they marched towards Leipzig on 2 May. Between 26 and 30 April Wittgenstein’s forces concentrated around Zwenkau with Blücher at Borna. By the evening of 30 April the French army and that of the Allies were so close to each other that a battle was inevitable.

Russian dragoons. The Allies enjoyed superiority in both the number and quality of their cavalry. The Russian dragoons were standard battle cavalry. (Richard Knötel)

Lacking sufficient cavalry, the information Napoleon had on the evening of 30 April about Allied movements was sparse. He expected the Allied headquarters to display little energy and to be able to defeat Wittgenstein at Altenburg before moving on Blücher’s rear. His orders for 1 May indicate that he was expecting a battle that day. Ney was to move on a wide front on Lützen. Marmont was to get as close as possible to Weissenfels to support Ney if required. Eugène was to move via Merseburg towards Schladebach and if he heard gunfire coming from Lützen to move against the Allies’ flank.

At 9.00a.m., Ney’s Corps started moving and around 11.00a.m. his vanguard reached the village of Rippach, where it clashed with Wintzingerode’s forward units under Lanskoi. The French pushed them back easily, but during the action a cannonball fatally injured the commander of the Guard Cavalry, Marshal Bessières. That afternoon, the artillery of both Corps engaged each other between Röcken and Starsiedel, the duel ending with the Allies withdrawing behind the Flossgraben. Ney followed up as far as the village of Kaja, where he established his headquarters. While his vanguard and Souham’s Division bivouacked between the villages of Kaja, Rahna, Grossgörschen and Kleingörschen, his other divisions spent the night at Starsiedel, Kaja and Lützen. While Marchand’s Division covered the crossing of the Flossgraben on the road from Lützen to Leipzig, the divisions of Compans and Bonet from Marmont’s Corps came up behind Ney, along the road from Weissenfels to Rippach. Friedrich’s Division was still at Naumburg, about 13 km from Weissenfels.

During the course of the day, Bertrand’s Corps moved up to the area around Jena, while Oudinot’s Corps reached Kahla. Roguet’s Division, now detached from Eugène, rejoined the remainder of the Imperial Guard at Weissenfels.

Eugène’s Army of the Elbe marched via Rippach towards the sounds of the guns. By evening, it had linked up with Lauriston and Latour-Maubourg in the area of Markranstädt. Durutte’s Division, now 4,000 men strong thanks to the transfer of five battalions from Marmont’s Corps, reached Merseburg. Napoleon now had 144,000 men and 372 guns within striking distance of his enemies, but of this formidable force only 7,500 were cavalry.

Should a battle take place, Wittgenstein was in a position to call on 88,500 men (19,000 of which were cavalry), 5,000 Cossacks and 552 guns. However, faults in the Allied command structure were going to make it difficult for him to do so. For the proposed Allied flank attack to succeed they would need to move swiftly and decisively and the attacks would need to be co-ordinated. Under any circumstances this level of organisation was a daunting task. With a multinational force that had not fought together before and in which certain commanders were, for their own reasons, being less than fully co-operative it would be doubly difficult.

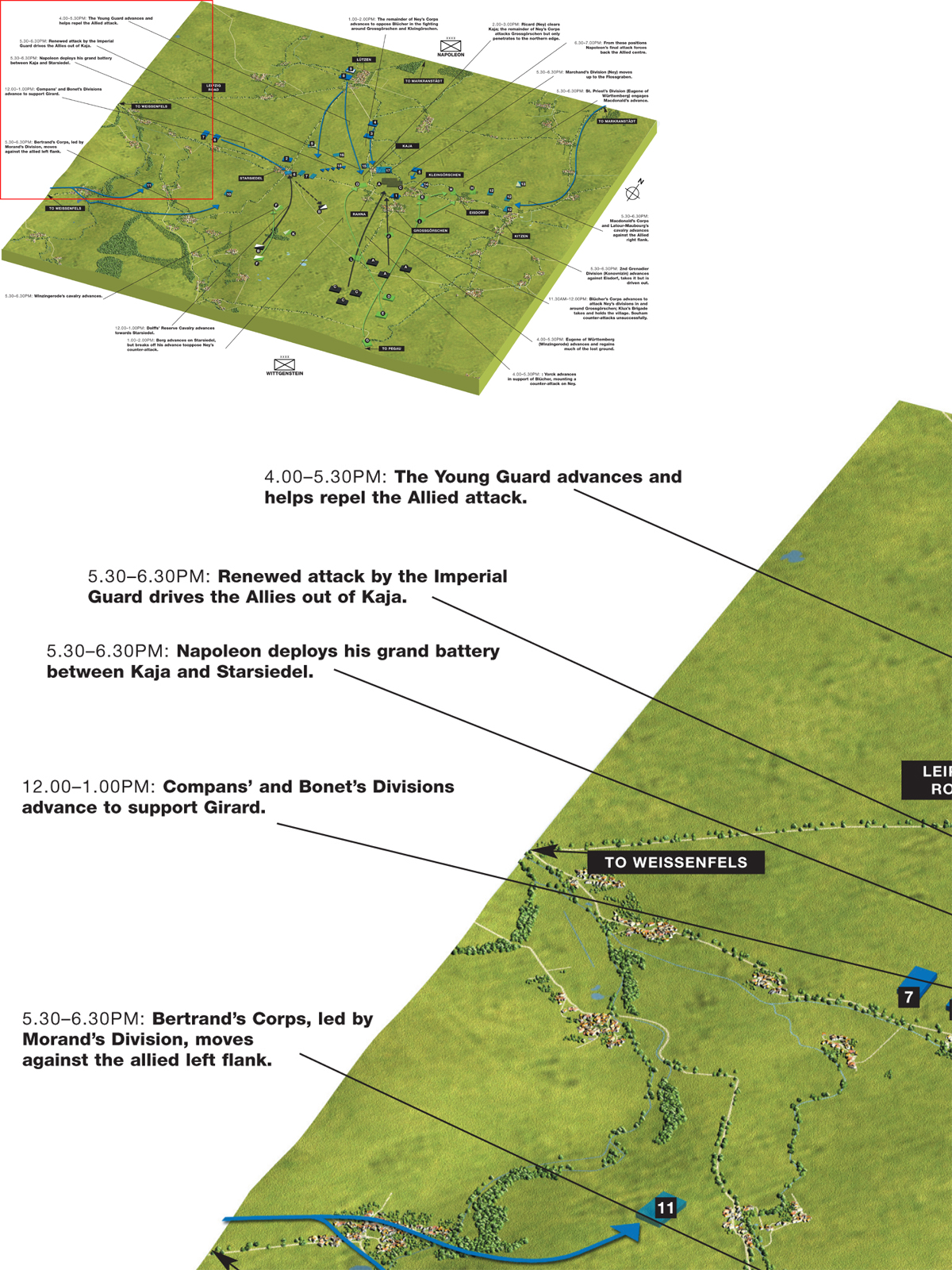

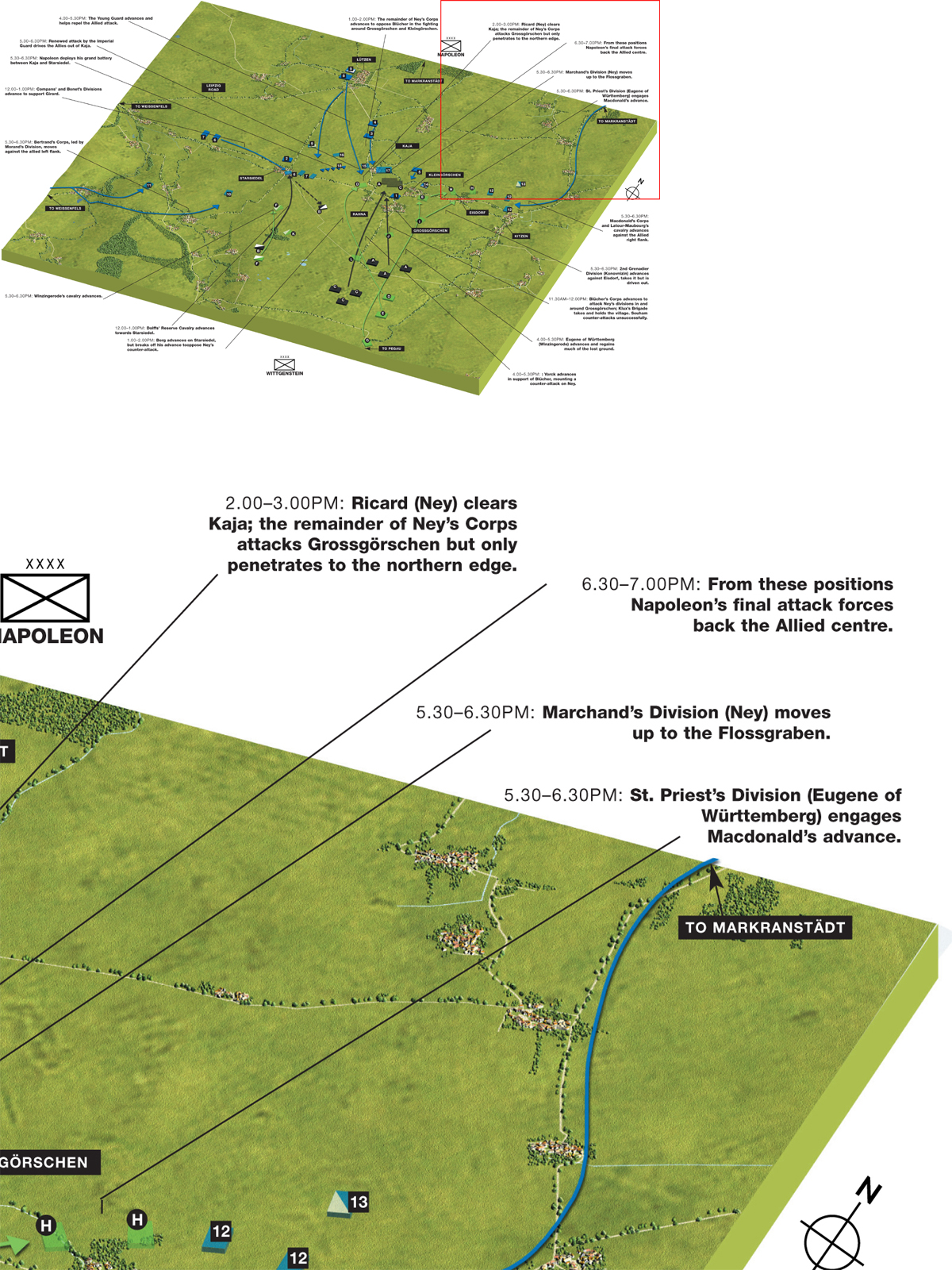

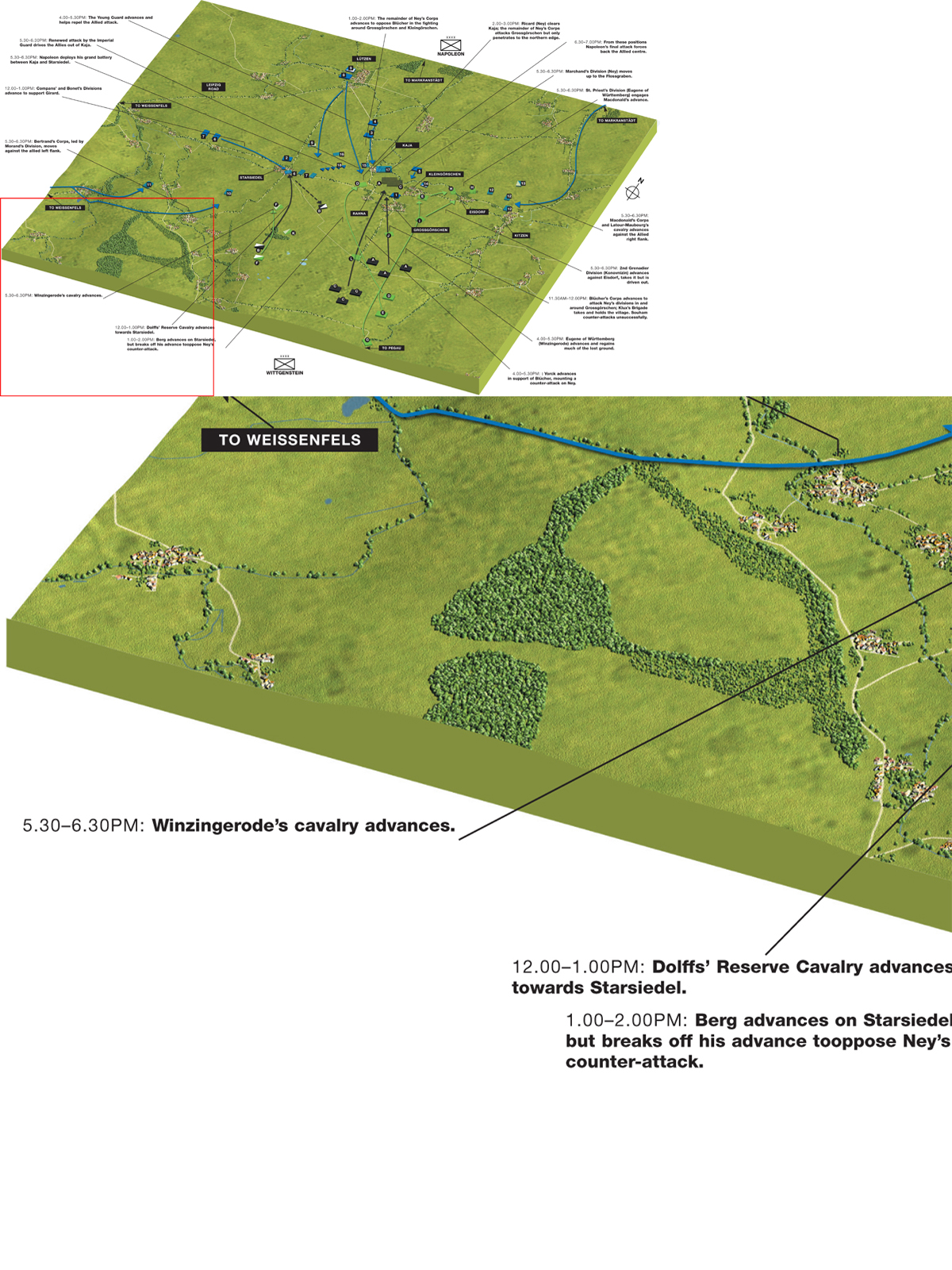

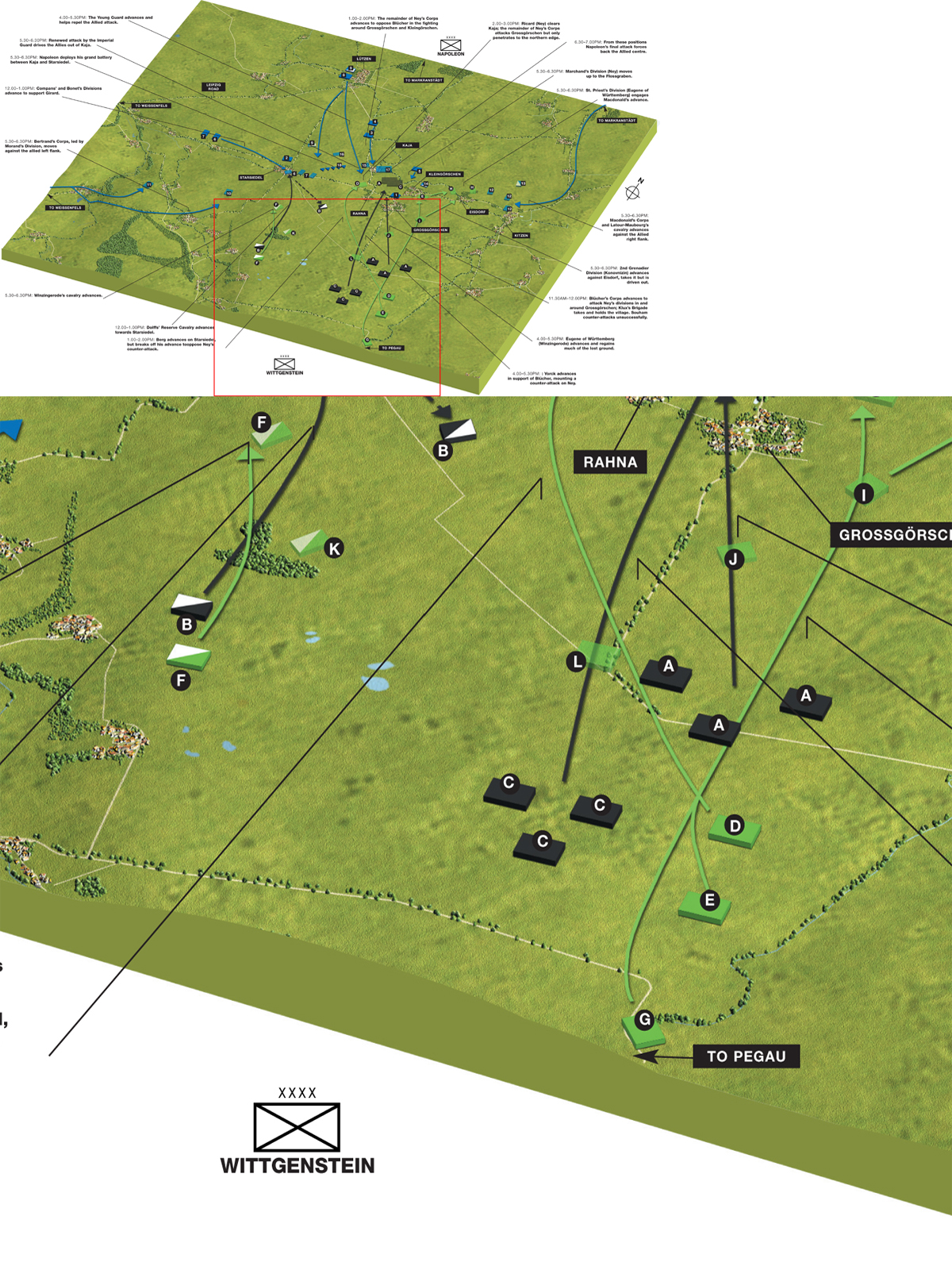

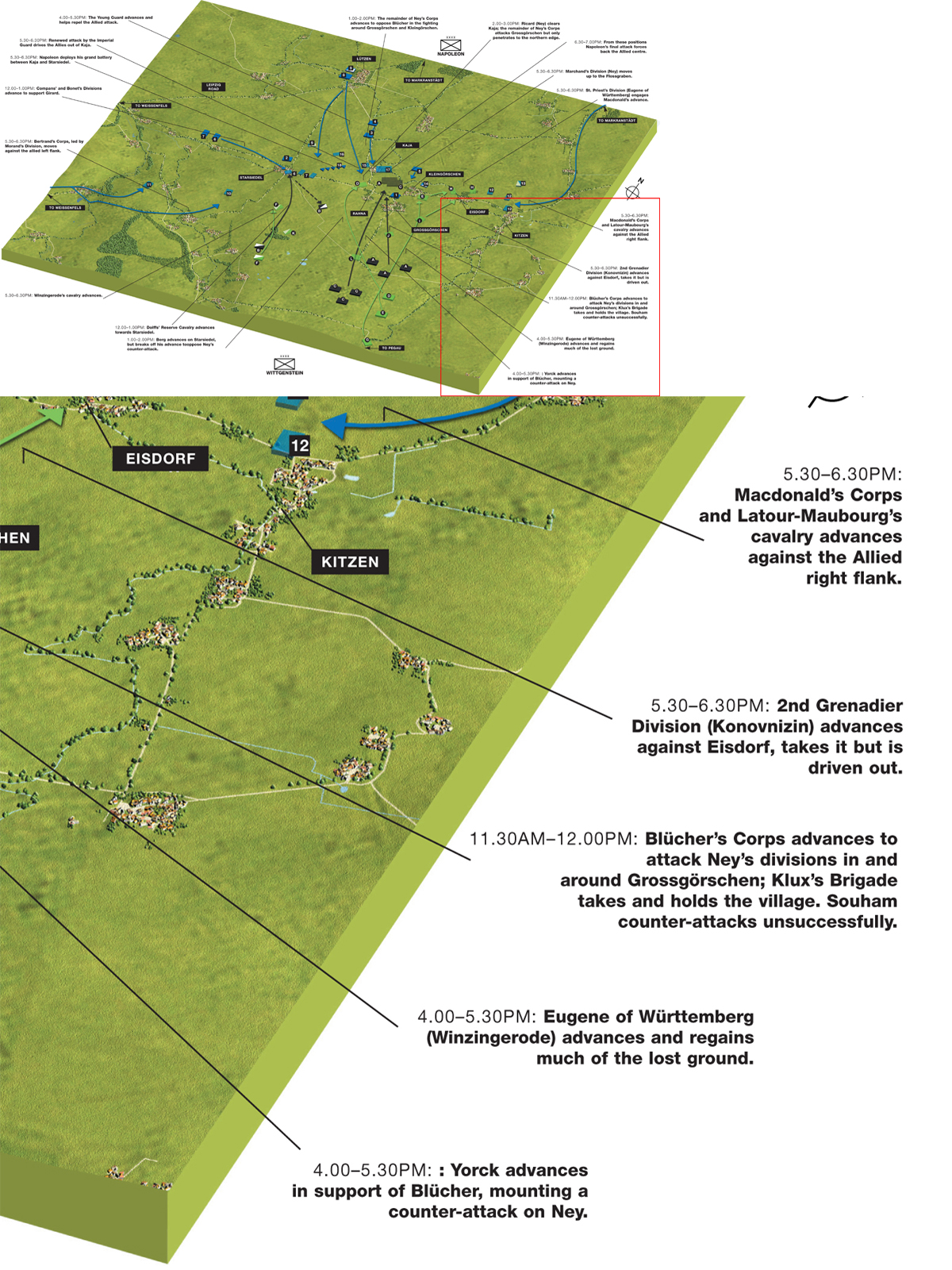

2 May 1813, 11.30am–6.30pm, viewed from the south east showing the initial Prussian and Russian attacks around Grossgörschen and Starsiedel, the French counterattacks and the flanking movements of Bertrand’s and Macdonald’s Corps.

FRENCH

1 Souham’s Division (Ney)

2 Girard’s Division (Ney)

3 Brenier’s Division (Ney)

4 Ricard’s Division (Ney)

5 Marchand’s Division (Ney)

6 Compans’ Division (Marmont)

7 Bonet’s Division (Marmont)

8 Imperial Guard (French)

9 Guard Cavalry (French)

10 Morand’s Division (Bertrand)

11 Peyri’s Division (Bertrand)

12 Macdonald’s Corps (French)

13 Latour-Maubourg’s Cavalry Corps (French)

14 Kellermann’s Cavalry

15 Young Guard (French)

16 Old Guard (French)

17 Ney’s Corps (French)

18 Grand Battery (French)

NB Solid symbols show first positions; ‘ghosted’ symbols show second positions.

PRUSSIANS

A Blücher’s Corps (Prussians): Zieten’s & Klux’s Brigades in front line, Roeder’s in second line

B Dolffs’ Reserve Cavalry (Prussians)

C Yorck’s Corps (Prussians)

RUSSIANS

D Berg’s Corps (Russians)

E Eugene of Württemberg’s Corps (Witzingerode) (Russians)

F Wittgenstein’s Cavalry

G Russian Guard and Grenadiers

H St. Priest’s Division (Eugene of Württemberg)

I 2nd Grenadier Division (Konovnizin)

J 1st Grenadier Division (Konovnizin)

K Gallitzin’s Cavalry Corps

L Russian Reserve

NB Solid symbols show first positions; ‘ghosted’ symbols show second positions.