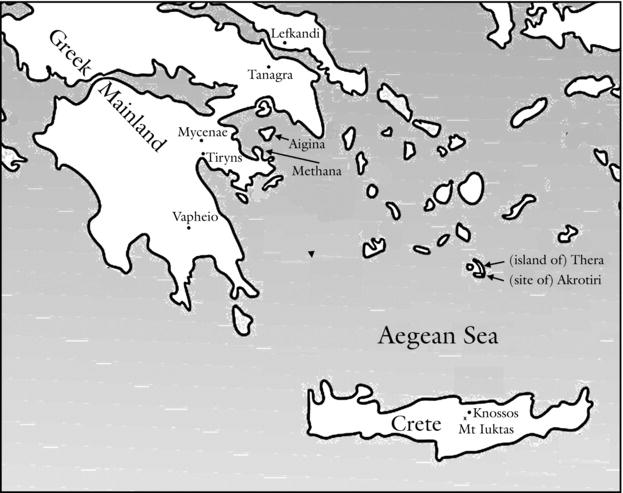

Map 2.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

No written text concerning sport has yet been discovered in any of the various scripts utilized by the Minoan, Cycladic, or Mycenaean cultures of the Aegean Bronze Age (c.3000–c.1100 BCE). Thanks to the extraordinarily rich range of Aegean pictorial art, however, illustrations of Bronze Age sport have survived in substantial numbers.1 Unfortunately, all too many of the objects that are the vehicles for these depictions are fragmentary, with the result that the more complex compositions that decorated the larger ones are woefully incomplete. Such vagaries of preservation, along with the absence of complementary literary sources, cause considerable disagreement among specialists as to how individual figures and actions are to be restored and interpreted. It is therefore hardly surprising that overviews of Aegean Bronze Age sport differ considerably (Laser 1987; Golden 1998: 28–33; Miller 2004: 20–30; Kyle 2007: 38–53).

Notwithstanding the deficiencies of the basic evidence, detailed study of Aegean Bronze Age sport has much to offer. Depictions of sporting activities begin as early as the end of the third millennium and are quite common in the sixteenth through the twelfth centuries BCE. During those five centuries, the images are deployed on a wide range of objects produced in various materials and scales within at least two and arguably three distinct cultural milieus (Minoan on Crete, Mycenaean on the Greek mainland, and Cycladic in the central Aegean islands, see Map 2.1), each of which passed through several sociopolitical stages that might have had an impact on the nature and function of the culture’s pictorial art. The evidence available thus lends itself to both cross-cultural (Minoan versus Mycenaean) as well as historical analysis in addition to forcing researchers to confront the basic question of how to investigate a culture’s self-representation with respect to sport on the basis of pictorial evidence. For such investigations to produce credible results, however, they must adopt rigorous methodologies including strict attention to chronological differentiation of the evidence, its spatial and sociopolitical contexts, and the functional implications of the artifact forms on which the images in question appear.

Map 2.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

Diachronic surveys of the depictions of sport during the Aegean Bronze Age typically begin with the pair of almost complete terracotta rhyta in the form of bulls from the Prepalatial Minoan tholos tombs at Koumasa and Porti (Younger 1995: 525 nos. 9, 7). Standing 10–15 centimeters high and measuring 15–20 centimeters in length, these ritual pouring or decanting vessels (Koehl 2006: 259–76) were decorated with vertical banding or a rectangular patch of cross-hatching. Hanging onto their horns, and in one case draped lengthwise over the front of the bull’s head, are diminutive, belted, but otherwise nude, male figures, three on the three-legged Koumasa vessel and just one preserved on the single surviving horn of the Porti rhyton. A fragment preserving a bull’s horn clutched by an incomplete human figure from the peak sanctuary on Mt Iuktas (Younger 1995: 525 no. 8) is evidence for a third such vessel from a cultic but non-funerary context. The broadly cross-hatched rectangle across the back of the Porti vessel has suggested a net to many scholars, the means by which bulls were captured in the wild in later Neopalatial depictions (Koehl 2006: 328). An occasional contemporary and numerous later bull rhyta bear similar netlike decoration (Younger 1995: 525 nos. 14–18; Koehl 2006: 16–17, 72–5 nos. 10, 15–17, 19–23, pls. 1–3), but the small-scale human figures clustered around the bull’s head disappear after the Prepalatial era. These vessels presumably functioned as dispensers of libations, possibly in connection with the sacrifice of captured bulls (Koehl 2006: 327–9) and mostly in the context of public funerary rituals, to judge from the contexts of their discovery in areas adjacent to but outside of the actual tombs. The enormous size of the bulls relative to the male figures hanging from their horns and heads has suggested that bulls of the large and now extinct Bos primigenius species are intended, bones of which have in fact been recovered from Minoan excavation contexts at the sites of Tylissos and Chania (Marinatos 1993: 291 n. 61; Hallager and Hallager 1995: 557). Most commentators see in these early rhyta the first manifestation of the Minoans’ later well-known predilection for bull-related sports (e.g., Marinatos 1989, 1994), although the few terracotta rhyta to which human figures are attached date at least four centuries earlier than the abundant Neopalatial depictions of bull vaulting and bull grappling, with no apparent continuity in the iconography of bull sports during the intervening Protopalatial era and thus no clear indication that the Prepalatial and Neopalatial activities are connected, or if so, how.

Illustrations of activities that can be described as sport are extremely rare during the Protopalatial period in Crete despite the notable rise in the overall quantity of representational art. Thus the depiction of a male acrobat performing a backward somersault found on a sword pommel from the palace at Malia and dating to late in this period assumes considerable importance (Pelon 1985). Despite its excellent preservation, there is unfortunately nothing in the depiction of this figure to inform us as to the physical or social context in which it may have taken place. The acrobat’s costume differs appreciably from that of later bull jumpers, and the date of the piece (Kilian-Dirlmeier 1993: 18 nos. 32–3 for the swords from the same context) suggests that it ought to be viewed as part of a wave of Egyptian influence that had a clear impact on several different Minoan pictorial media toward the end of the Protopalatial era (Immerwahr 1985).2

The explosion of pictorialism that characterizes the Neopalatial era introduces figured murals as well as stone vessels decorated with representational scenes in relief to the repertoire of Minoan representational art. Illustrations of sporting activities appear in both of these new media and also make an appearance in more rarely documented materials such as painted rock crystal (Younger 1995: 534–5 no. 116; Evans 1930: 108–11, figs. 60–1, pl. XIX) and small-scale ivory sculpture in the round (Evans 1930: figs. 294–300; Lapatin 2001: 21–37). The vast majority of the roughly 100 different objects or surfaces decorated with Neopalatial sporting images feature scenes of bull leaping, bull vaulting, bull grappling, and bull catching (Younger 1995: 524–35, 539–41), but some 10–20% depict scenes of unarmed combat, usually identified as boxing but perhaps also including a form of wrestling, between pairs of youthful males (Coulomb 1981; Militello 2003: 359–77, 395–6). There are also a handful of images of acrobats doing handstands (Shaw 1995: 112 n. 81; Hood 1978: 228 figs. 231–2; Corpus der minoischen und mykenischen Siegel I 131, I Supp. 169a, III 166a, VI 184) and a couple that illustrate runners possibly engaged in some form of competition (Lebessi, Muhly, and Papasavvas 2004; Koehl 2006: 180 no. 765, pl. 47).3

Aside from two famous gold cups from the tholos tomb at Vapheio,4 all the complex compositions of sporting scenes in Neopalatial art are highly fragmentary, with the result that what they actually show is often as much debated as their larger significance. A high percentage of the depictions of bull-related sports consist of images executed at a miniature scale on carved sealstones and signet rings that typically include just two or three figures (Younger 1995: 539–41). Yet even when images of comparable activities are executed at significantly larger scales in relief on stone vases, in painted plaster, or at life size in stucco relief, they may often have been as sparely composed, as is likely to have been the case with respect to sculptural groups executed in mixed materials including ivory (pace Evans 1930: 428, 435; see Lapatin 2001: 23–4).

Neopalatial bull sports (usefully surveyed in Younger 1995; Scanlon 1999; and Panagiotopoulos 2006) appear to have been performed largely, indeed perhaps exclusively, at Knossos (Shaw 1995: 98–104, 113–19; Hallager and Hallager 1995). The scheduling and frequency of these performances are unknown but are suspected of having been regular but only occasional (Younger 1995: 521–3). Exactly where at Knossos the performances took place and whether or not the venue was always the same are likewise uncertain (Younger 1995: 512–15; Panagiotopoulos 2006: 130–1), but a better case can presently be made for a location outside of the palace proper than within it, perhaps to the west and north of the West Court as proposed by Shaw (1996: 186–9, fig. 7).

The identity of the leapers has attracted perhaps more scholarly attention than any other facet of this distinctive sporting activity, chiefly because of the widespread and persistent conviction among commentators that the red and white skin colors of the jumpers depicted in the (somewhat later) Taureador fresco indicate that jumpers of both sexes participated in this dangerous pastime (Younger 1995: 515–16; Panagiotopoulos: 128–9). Alberti, however, following up on comments by Damiani Indelicato (1988) and others, has pointed out the extent to which seemingly standard skin-color conventions for the sexes are ignored by Knossian artists and has drawn attention to how leapers in the Taureador fresco are individualized through the decoration of their breechcloths, their jewelry, their gestures, and probably even their heights (Alberti 2002: 103–4, 111–12). Gender evidently does not play a role in a leaper’s identity. The absence of any evidence for female jumpers in other media such as ivory carving supports the view that all bull jumpers were, in fact, male, and that the distinction between red-skinned and white-skinned bull jumpers and bull grapplers in some paintings at Knossos, and perhaps also in contemporary Minoanizing frescoes at Tell Dab’a-Avaris in the eastern Nile Delta (Bietak, Marinatos, Palivou, et al. 2007), has some significance other than sexual differentiation.

On present evidence, only when a painting was executed with figures at a miniature scale was the setting of bull sports represented. At least three such compositions may once have existed in the palace at Knossos (Shaw 1995: 102, 117–18): (1) the so-called Ivory Deposit fresco in which a bull (but unfortunately no preserved leapers) and an architectural façade appear, together with which fragments of at least four ivory human figures were found, some of them certainly male bull jumpers (Evans 1930: 397–435; Shaw 1995: 118, fig. 8:F, 1996: 182); (2) a collection of fresco fragments from below the thirteenth magazine that includes one with a bull’s head and the flying tresses of a leaper plus other pieces depicting a crowd of spectators and also an architectural façade (Shaw 1995: 117–18, fig. 8:B, 1996: 183–4, pl. 36b–d; for Cameron’s 1974 reconstruction of this composition within a large panel, Bietak, Marinatos, Palivou, et al. 2007: 89 fig. 90); and (3) the Grandstand and Sacred Grove frescoes depicting crowds, a complex architectural façade including a tripartite shrine, and an exterior court, but no bulls or leapers actually preserved (Davis 1987; Shaw 1995: 118, fig. 8:C; 1996: 185–8, pl. 37). The importance of the thirteenth magazine fragments for the evidence they provide of the combination of bull leaping, spectating crowd, and architectural setting within a single composition is enormous inasmuch as they furnish strong support for the unifying social function of bull jumping within what are likely to have been public spaces immediately adjacent to the Knossian palace (Panagiotopoulos 2006: 130–3).

Discoveries during the 1990s of bull-jumping activities illustrated on a Hittite relief-decorated cult vessel found at Hüseyindede in Anatolia and dated to the sixteenth century BCE (Sipahi 2001) and in early fifteenth-century BCE frescoes from Tell Dab’a in the eastern Nile Delta (Bietak, Marinatos, Palivou, et al. 2007), along with the publication of similar activities on long-known and even older seals from Syria (Collon 1994), have shown bull-related sports to be widespread among eastern Mediterranean cultures and to have putative ancestors in Egypt and Anatolia (Morenz 2000). While some examples of such events in art are clearly derived from Minoan models (for example, those depicted in the Tell Dab’a murals), others appear to differ in most respects from Minoan representations and may have little or no connection with the bull sports developed on Crete. It therefore seems unwarranted to claim that Hittite material supporting an interpretation of such activities as principally religious in character should be applied to Minoan bull sports (Taracha 2002: 19), especially when most commentators are inclined to view the Minoan practices as initiation rituals undertaken by youthful Minoan males whose decorated breechcloths, fancy jewelry, and elaborate hairstyles identify them as members of the Cretan elite (Säflund 1987; Alberti 2002). The stress on crowds of spectators witnessing these events that seems to be a feature of some miniature-style frescoes from Knossos further suggests that the staging of these spectacles constituted an important ingredient in promoting societal cohesion on Neopalatial Crete as Minoan culture became increasingly subject to the dominance of Knossos.

Whereas bull-jumping events appear to have been hosted only at Knossos in the Neopalatial era, and therefore may have become an emblem of Knossian political power on items such as gold rings (Shaw 1995: 104–5), unarmed combat between pairs of young males, though much less commonly illustrated, was seemingly practiced more widely as well as more variably (Coulomb 1981). A single, almost fully restorable, wall painting from Room B1 at Akrotiri on the island of Thera shows two young boys between the ages of 6 and 10 in active combat, each outfitted with a single dark glove on his right hand (Doumas 1992: 108–15, figs. 78–81; Morgan 1995; Chapin 2007: 240–1, 251–2, figs. 12.6–12.7). The two boys are purposefully juxtaposed with two antelopes on an adjacent wall, one of a trio of such antelope pairs that decorated the other walls in this room. The boys’ age, in addition to the formal comparison between their activity and the ritualized competition of the two closest antelopes (Morgan 1995: 184), indicates that they are engaged in practice sparring, not violent or destructive combat. The clear status difference between the victorious boy on the left, conspicuously outfitted with elaborate jewelry, and his much more plainly attired opponent is matched by an apparent difference in their skill levels: the former effortlessly wards off his antagonist’s blow at the same time as he readies a counterpunch. As Nanno Marinatos notes, “the message of the painting is firstly competition through play and secondly establishment of hierarchy: the victor is obvious through posture and adornment with jewelry” (1993: 212).

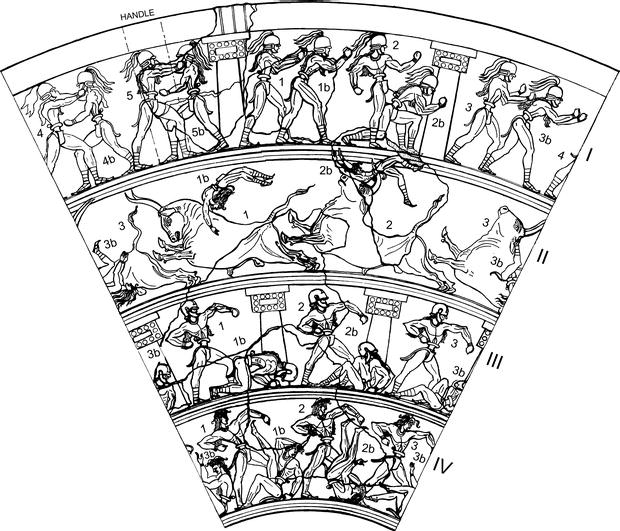

The contrast with the three different varieties of unarmed combat that decorated three of the four friezes on the famous Boxer Rhyton from Ayia Triadha in Crete (see Figure 2.1) could not be greater. Differences in equipment (principally headgear and footgear) worn by the combatants in each of friezes I, III, and IV (counting from top to bottom, as in Robert Koehl’s new reconstruction (2006: 164–6, Frontispiece, fig. 29, pl. 41)) suggest that different rules may apply to the combat events illustrated, just as the presence of columnar supports topped by capitals in only two of the three (I, III) may hint at different venues for their staging. Although the highly fragmentary state of the rhyton’s preservation precludes certainty on this point, it is likely that each of the three lower friezes (II–IV) depicted three pairs of antagonists; in every case where the preservation allows a determination to be made, the victor is clearly identified.

The Boxer Rhyton is by no means the only Neopalatial stone vessel to have been decorated with scenes of sport, but it is the only such vessel to consist of more than a single fragment. At least five additional rhyta, all found at Knossos, bore scenes of boxing (Koehl 2006: 180 no. 766), bull jumping (Koehl 2006: 181 no. 770), either one or the other of these two activities or perhaps simple acrobatics (Koehl 2006: 180–1 nos. 767–8, pl. 47), and possibly competitive running (Koehl 2006: 180 no. 765, pl. 47). Rhyta in the Neopalatial and subsequent Monopalatial eras are carried only by male figures in Aegean art (Koehl 2006: 336). Furthermore, such human figures as appear on stone rhyta decorated in relief with pictorial scenes are exclusively male (Warren 1969: 174–81). These facts, in addition to the specific pictorial content appearing on some of these vessels, have led Koehl to interpret the images on several of the best preserved examples, including the Boxer Rhyton, as illustrations of male initiation rituals (2000, 2006: 335–7). The deployment of sporting imagery on this particular artifact form on objects produced exclusively at Knossos and intended for male usage strongly supports the evidence provided by the Neopalatial frescoes decorated with similar imagery (Shaw 1995), although nothing indicates that this iconography need be specifically royal in character (contra Marinatos 2007). The artifact categories on which this imagery is principally employed, though all of elite character, put no emphasis on royal personages but rather highlight the physical aspirations and achievements of what appear to be Knossian society’s elite male youth (Säflund 1987; Koehl 2000). Competition is pervasive in this art, but there are no depictions whatsoever of rewards for victory.

Figure 2.1 Restored line drawing of the Boxer Rhyton, c.1550–1500BCE.Source: From R. Koehl,Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta, frontispiece, image courtesy of INSTAP Academic Press. Used with permission.

Following the destruction of most palatial structures and virtually all known outlying “villas” on Crete within a fairly short space of time during the early fifteenth century BCE, the single surviving palace at Knossos flourished under an administration that maintained its records in Mycenaean Greek in the Linear B script for a period of two to three generations before itself falling victim to a wholesale destruction by fire that put an end to that site’s short-lived but seemingly uncontested dominance (hence the term “Monopalatial” for the timespan). Even more than had been true during the later stages of the preceding Neopalatial era, the production of most classes of pictorial art on Crete during this Monopalatial period was concentrated at or near Knossos. Among these are such famous murals as the Taureador fresco (the most fully preserved of all fresco renderings of bull-leaping activity (Marinatos and Palivou 2007)) and a relief-decorated ivory pyxis (Hood 1978: 121–2, fig. 111) that depicts a monstrously large bull being hunted and simultaneously either grappled with or vaulted by three youths in a rural landscape. This pyxis, clearly indebted with respect to technique and subject matter to Neopalatial predecessors such as the twin gold cups found at Vapheio and stone rhyta manufactured at Knossos, presents us with a thus far unique composition of bull hunting and bull jumping in the wild that has its closest analogue in the Violent Cup from Vapheio.

Within each of the constituent panels of the Taureador fresco (of which Marinatos and Palivou (2007: figs. 104, 107–9, 112) have identified a minimum of five) a single bull charging from right to left is matched against a pair or trio of bull jumpers and bull grapplers. The removal from this compositional schema of all landscape and architectural elements as well as any indication of spectators may signal a profound change at this time in the display of bull-related activities in Aegean art, but the surviving evidence is unfortunately too exiguous to allow for anything resembling certainty on this point.

After the destruction by fire of the palace at Knossos early in the fourteenth century, the production of seals (a signet with a raised or incised emblem used to stamp an impression on substances such as unfired clay or perhaps wax) in hard stones appears to have come to an end while that of gold signet rings declined markedly. As a consequence, very few depictions of bull jumping on sealstones and signet rings can be assigned dates of production later than roughly 1375 BCE (Younger 1995: 532 no. 98). Prior to this date, however, scenes of bull-related sports continued to be as popular in this medium as they had been in Neopalatial times. Indeed, they perhaps became even more popular in the Monopalatial era (Younger 1995: 539–41).

Broadly contemporary perhaps with the Taureador fresco are less than a dozen fragments of a fresco featuring bull leaping recovered from the strata beneath the Ramp House at Mycenae on the Greek mainland (Shaw 1996: 167–80, color pls. A–B). About half of these can be assigned to two panels containing a large bull, one of them also featuring at least three human figures identifiable as bull jumpers or bull grapplers. Four further fragments depicting an architectural façade within whose window embrasures are several female spectators may belong to the same composition by virtue of their similar figure scale, but these preserve no portion of the framing border that is a distinctive feature of the bull-jumping panels not only from Mycenae, but also of the Knossian Taureador fresco. It is therefore uncertain whether the spectating women are to be understood as watching the bull-jumping activities within one and the same composition. The Mycenae frescoes securely identified as illustrating bull jumping are remarkably similar in their composition to those of the Monopalatial period at Knossos, even if their figure scale is approximately half that of their Knossian parallels (Shaw 1996: 182 n. 55). Moreover, of the four known or suspected examples of bull-leaping compositions in the fresco art of the Mycenaean Greek mainland (Shaw 1995: 119), the Ramp House fresco at Mycenae is unquestionably the earliest. It would therefore seem likely that the bull-jumping theme was initially distributed from Knossos to Mycenae in the form of fresco art shortly after the Linear B administration was installed at Knossos under the control of what is usually considered to have been a Mycenaean ruler. Only after a century or more was this theme passed along to palatial establishments elsewhere on the Greek mainland.

Neither boxing nor forms of acrobatics other than those performed in the context of bull jumping appear to have survived the Neopalatial collapse on Crete itself. Nor is there any secure evidence for the adoption of boxing or acrobatic iconography directly from the Neopalatial Minoan iconographic repertoire for the purposes of display on the Greek mainland. Instead, a limited number of paired boxers, not always portrayed in actual combat, turn up on a relatively small number of Mycenaean kraters (large vessels for mixing wine) found in tombs on Cyprus (Vermeule and Karageorghis 1982: 43–4, 202 V.28–32).5 Broadly contemporary and also from Cypriot contexts are two Mycenaean kraters depicting bull leaping (Vermeule and Karageorghis 1982: 25, 197 III.31 and 48, 203 V.48). A krater in Boston (USA), from an unknown locale on Cyprus, yet surely recovered from a tomb, depicts two pairs of males on opposite sides of the vase engaged in the Levantine sport of belt wrestling but with their arms held in much the same position as some of the previously cited boxers (Vermeule and Karageorghis 1982: 39, 201 V.14). No other evidence for this particular version of unarmed combat is known from the Aegean, so this may have been an item of iconography inserted specifically to appeal to a Cypriot or other Levantine consumer.

Only two Mycenaean pictorially decorated vessels of the palatial era illustrating sporting events – a krater sherd plausibly depicting a pair of boxers confronting each other (Vermeule and Karageorghis 1982: 93, 212 IX.17) and a rhyton sherd featuring a helmeted bull jumper in mid-leap over the back of a bull (Vermeule and Karageorghis 1982: 93–4, 212 IX.18.1) – have been found on the Greek mainland, both in settlement contexts at Mycenae. A third pictorial fragment, a krater sherd showing parts of two males confronting each other, at least one of them seemingly armored and both with a single arm raised, has been identified in the past as depicting boxers (Vermeule and Karageorghis 1982: 93, 212 IX.18) but more probably represents saluting warriors (Crouwel 1991: 16 B1, pl. 1).

So far as Mycenaean pictorial vase painting is concerned,6 it seems legitimate to conclude from this survey of the surviving evidence that vessels with scenes of sport were intended primarily for viewing audiences on the island of Cyprus (van Wijngaarden 2002: 183–202). Moreover, within such Cypriot contexts, scenes of sport appeared overwhelmingly on kraters designed for the mixing of wine with water for the purposes of communal consumption in small to medium-sized groups, although smaller numbers of open vessels from which wine would have been consumed by individuals (kylikes, bowls) were also sometimes decorated with such scenes. On the Greek mainland, pictorially ornamented ceramic vessels of the palatial era bearing scenes of sport are few and far between and have thus far been found exclusively at Mycenae, with the single exception of a well-known larnax from Tanagra Tomb 22 (Younger 1976: 133 III.2, 1995: 531 no. 84).

If one considers the vase-painting evidence in concert with that for scenes of sport in Mycenaean mural paintings, one might hazard a guess that depictions of bull-related sports in painting were intended for royal consumption only. The small number of vessels decorated with this iconography that were exported to Cyprus may thus conceivably have been royal gifts, the products of an industry centered in the kingdom of Mycenae (Åkerström 1987; Mommsen and Maran 2000/1), which we now know, from numerous programs of chemical analysis (e.g., Zuckerman, Ben-Shlomo, Mountjoy, et al. 2010), produced by far the largest percentage of Mycenaean decorated pottery exported to Cyprus and the Levant from any production center on the Greek mainland. The same royal monopoly that applied to depictions of bull jumping may likewise have covered scenes of boxing, although in the case of that sport there is no indication in Mycenaean fresco art that this subject was restricted to royal residences. In his publication of the large quantities of pictorial pottery recovered from one, if not the chief, production center of Mycenaean pottery of this kind during the palatial era, Åkerström argued that the comparatively few figures identified as boxers in Mycenaean vase painting had been taken over from personages identified as “grooms” and simple “attendants” in Syrian and Egyptian New Kingdom art and in his opinion had nothing to do with boxing at all (1987: 79–83). In rejecting Åkerström’s arguments, Benzi (1999: 221–2) nevertheless concedes that the Mycenaean approach to portraying boxers in painting is quite different from that of earlier Neopalatial depictions on Crete, especially in opting for a more balanced, emblematic, or heraldic presentation of the combatants rather than putting emphasis on the moment of victory that figures so prominently on the Boxer Rhyton. Mycenaean boxers thus lend themselves to being interpreted as the providers of entertainment at social occasions when the kraters and other drinking vessels on which they appeared were put into use, that is, as hirelings of an elite for whom the pictorial kraters were produced rather than as themselves members of the elite going through some form of initiation, as has been argued to have been the case for Minoan boxers.

The relatively recent discovery in situ in a fourteenth to thirteenth century BCE shrine building at Ayios Konstantinos on Methana of three fragmentary but largely restorable terracotta figurines depicting single, presumably male human figures standing on the shoulders of bulls, their forward-facing heads framed within the curving arc of the horns that they grasp with both hands, has come as something of a surprise (Konsolaki-Yiannopoulou 2003a: 377–8, figs. 10–12). Though similar figurine groups have long been known from single examples in museums in Lefkosia (Cyprus) and Princeton (USA), these parallels lacked proveniences of any kind, while fragments of potentially comparable figurines from Mycenae and the Aphaia sanctuary on Aigina derive from fills that provided no significant information concerning the original usage of the objects to which they had belonged (Konsolaki-Yiannopoulou 2003a: 377 ns. 13, 15–17). Found together with substantial numbers of other comparatively unusual multifigure terracotta groups (e.g., chariots, ridden horses, and ox-drawn carts), the bull-jumping groups from Methana have been interpreted as evidence for the worship of a male divinity associated with bulls and horses. The association of bull jumping with cult at this remote Mycenaean sanctuary has no obvious connections with either Minoan or Mycenaean palatial practices, although it is tempting to suggest that these terracotta groups were produced at and distributed from either Mycenae or Tiryns, the nearest palatial centers to the Ayios Konstaninos shrine.

The complex iconography decorating a larnax (rectangular chest) evidently reused as an ossuary in Chamber Tomb 22 at Tanagra has been subjected to detailed analysis by Mario Benzi with the aim of testing Decker’s earlier thesis that several of the scenes represented are to be understood as depictions of Homeric-style funeral games held for the child shown being lowered into his coffin (Decker 1987; Benzi 1999: 215–17, figs. 1–2a). What Decker took to be an armed duel observed by the multiple occupants of two antithetically disposed chariots in the lower register of one long side, Benzi reinterprets, to my mind compellingly, as a boxing scene (1999: 219–22). He subsequently draws attention to the various unique features of the bull-jumping scene that appears in a comparable position on the opposite long side: three bulls standing stationary, each with a human vaulter positioned horizontally above its back, while the horns of the two antithetically posed bulls are grasped by an off-axis “master of animals” figure (1999: 226–9). Why should scenes such as these have decorated the burial container of a child or adolescent who, to judge from the modest grave goods recovered from the tomb, did not possess any particularly elevated status within the community buried around him (or her) in dozens of other tombs nor even within the smaller social group interred in the same tomb? The painted decoration of this terracotta sarcophagus is exceptional in so many ways that Benzi must be correct in viewing it as an object made to order for a particular individual (1999: 229–31). There is no good reason to assign a specifically funerary interpretation to the sporting activities illustrated on it, especially when the activities in question (bull jumping and boxing, for example) have no specifically funerary connections in an Aegean Bronze Age context. Most of the events associated with later Iron Age funeral games are conspicuous by their absence (see Chapter 3 in this volume). For example, there is nothing in the two chariots carrying multiple passengers and facing in opposite directions on one side of the Tanagra chest to suggest a chariot race. Benzi concludes that the larnax’s iconography may have been connected with the youngster buried within it through the initiation rituals that are represented by the sporting events depicted, even though the actors in these events all look to be adults rather than either children or adolescents. There is no simple answer to the interpretative problems posed by this unique artifact, but Benzi performs a genuine service by casting Decker’s view of it as an illustration of Bronze Age funeral games (for which there continues to be no compelling evidence on either Crete or the Greek mainland, apart from Homer’s epic narrative) into serious doubt. In view of how unusual larnakes are as burial containers on the Mycenaean mainland in the first place, it is perhaps not surprising that the iconography decorating some of them should be equally peculiar.

With the destruction of all known Mycenaean palaces within a couple of decades at the beginning of the twelfth century BCE, several major changes took place in the production and consumption of Mycenaean pictorial art (Rutter 1992; Maran 2006). Two of these merit special attention for the impact they had on depictions of sport. First, the ranges of materials and artifact categories that had been vehicles for pictorialism during the preceding era shrank dramatically, with the result that within a generation or less Mycenaean pictorial art was virtually restricted to painted pottery. Seal production had already declined considerably in both qualitative and quantitative terms after the destruction of Knossos c.1375 BCE; in the twelfth century and for three centuries thereafter, it ceased altogether (Krzyszkowska 2005: 232–5). Walls likewise ceased to be decorated with representational scenes in painted plaster, the number of pictorially decorated ivory objects declined precipitously, and neither weaponry nor containers produced in stone or metal were ornamented with representational images.

Second, many of the specific motifs that had been widely deployed in Mycenaean palatial art and that may be considered the basic elements of a royal iconography – boar’s tusk helmets, figure-of-eight shields, apotropaic creatures such as lions, sphinxes, and griffins – disappear so abruptly with the palatial collapse that their elimination from the pictorial record comes across as a purposeful rejection of the sociopolitical system in which they had flourished and for which they had become symbolic.7 In their stead, new forms of weaponry and altogether new scenes appear in Aegean art, the latter especially during a mid-twelfth-century pictorial renaissance that illustrates an altogether different Aegean society organized around significantly smaller, more highly differentiated, and probably also much shorter-lived polities (Dickinson 2009).

As far as illustrations of sport are concerned, these momentous changes resulted, not surprisingly, in the total disappearance from the pictorial record of bull-related sports and unarmed combat in the form of boxing, both argued to have been activities closely associated with, if not actually restricted to, palatial settings in the Mycenaean world. By far the most popular themes of twelfth-century Mycenaean art are warfare and the hunt, but also included are scenes of dancing and singing and at least one and perhaps as many as three examples of chariot racing, the first depictions of this activity in Aegean art (Vermeule and Karageorghis 1982: 126, 128, 221 XI.19, XI.37, 230 XI.19.1).

Thus far, such depictions of vehicular racing are the only clearly identifiable illustrations of sport known from the Postpalatial Bronze Age Aegean. In its choice not merely of an alternative iconography, but also of a completely different variety of physical competition based upon the strength and speed of multiple expensive animals and costly conveyances, the society that sponsored such races reveals itself to have been fundamentally aristocratic in nature, moreover one that reveled in the competition between several rather than just two contestants. Such a society is precisely that of the Homeric epics, so it is perhaps logical that vase painters of the twelfth century privileged the same kind of sporting competition as did Homer by making the chariot race particularly emblematic of their respective eras.

The one certain and two possible illustrations of chariot races respectively decorate a collar-necked jar from Tiryns8 and two kraters, one from Tiryns and one from Lefkandi. No longer are such scenes of sport in vase painting restricted to the single site of Mycenae as in palatial times; nor are they exported to Cyprus. The social, political, and economic circumstances of the Postpalatial Aegean were entirely different from those of just a century before. Just as scenes of warfare and the hunt were helpful iconographical tools during the turbulent years of the twelfth century as the decoration of communal drinking vessels used by local elites residing at sites such as Mycenae, Tiryns, Lefkandi, and Kynos to strengthen the social bonds between themselves and their comrades in arms, so depictions of the high-end sporting events in which only members of the elite warrior class of this era could participate serve the same purpose. The nature of the times dictated to a marked degree not only the preferred form of sport, but also the social venue in which images of this sport would be displayed. So it had been in the Bronze Age Aegean since Prepalatial times, and the artifactual vehicles for these sports’ depictions consequently assumed very different forms depending on the particular sociopolitical circumstances that prevailed at any one moment in time.

NOTES

1 Over the past three decades, an explosion of publications relating to Aegean Bronze Age sport has made clear how abundant the pictorial evidence is. Lists of the depictions of bull-related sports (Younger 1976, 1995), boxing and other forms of unarmed combat (Coulomb 1981; Benzi 1999: 219–22; Militello 2003: 359–77, 395–6), possible running and throwing events (Lebessi, Muhly, and Papasavvas 2004; Rystedt 1986, 1988), chariot racing (Kilian 1980; Crouwel 1981: 77, 119–20, 139, 142; Güntner 2000: 181 nos. 172 and 181, 195–6), and acrobats or tumbling (Demakopoulou 1989: 111–12) provide ready access to images.

2 The later LM IA dating proposed more recently by Demakopoulou (1989: 111–12 no. 5) is not supported by any reliable evidence.

3 I am grateful to John Younger for the references to these four Neopalatial seals as well as for drawing my attention to the gold ring from Kato Syme published by Lebessi, Muhly, and Papasavvas 2004.

4 Vapheio is located near the later site of Sparta on the Greek mainland. One of the two cups in question, the so-called Quiet Cup, has been interpreted as the work of a Neopalatial Minoan artisan that inspired the production of a thematically linked piece (the Violent Cup) by a mainland Greek artisan (Davis 1977: 1–50, 256–8 nos. 103–4).

5 Three bowl and kylix fragments from Kition and Kourion, apparently all from settlement contexts, may have shown similar boxing pairs, although in these cases only portions of single figures with arms upraised in appropriate positions survive (Vermeule and Karageorghis 1982: 44, 202 V.33–5).

6 Attempts (see Rystedt 1986, 1988) to identify competitions in running or even in spear throwing on a dozen Mycenaean pictorial kraters of LH IIIA–B date (nine from Cyprus, one each from Ugarit, near Aptera on Crete, and Corinth) have thus far not been sufficiently compelling to persuade skeptics that such activities flourished as actual sports in the Late Bronze Age Aegean.

7 These royal creatures survive only at Lefkandi in scenes where they have been converted from fearsome apotropaic beasts to caring parents in a series of scenes that seem to be conscious parodies of their earlier palatial usages (Crouwel 2006: 243–4, 254 G1, pl. 67; 244–5, 254 G2, pls. 68, 70; 242, 251 C3a–b, pl. 62).

8 Vermeule and Karageorghis (1982: 230) identify the footed object below the enthroned female figure on the Tirynthian jar as “a krater . . . set on a ringstand by the throne.” Crouwel (2006: 241 and n. 72) comments that the enthroned female “figure is accompanied by, or perhaps actually seated on, a tripod cauldron.” It seems quite possible that the krater or tripod cauldron next to the throne on the Tirynthian jar may have been intended to be viewed as a prize for the winner of the race. Vessels of this kind are, after all, routinely illustrated as prizes in scenes of sporting competitions of various kinds in Late Geometric and Archaic Greek as well as Etruscan art. If correctly identified, this would be the earliest athletic prize to be illustrated in Greek art.

REFERENCES

Åkerström, Å. 1987. Berbati II: The Pictorial Pottery. Stockholm.

Alberti, B. 2002. “Gender and the Figurative Art of Late Bronze Age Knossos.” In Y. Hamilakis, ed., 98–117.

Benzi, M. 1999. “Riti di passagio sulla larnax dalla Tomba 22 di Tanagra?” In V. La Rosa, D. Palermo, and L. Vagnetti, eds., 215–33.

Bietak, M., N. Marinatos, C. Palivou, et al., eds. 2007. Taureador Scenes in Tell el-Dab’a (Avaris) and Knossos. Vienna.

Borgna, E. and P. Càssola Guida, eds. 2009. Dall’Egeo all’Adriatico: Organizzazioni sociali, modi di scambio, e interazione in età post-palaziale (XII-XI sec. a.C.). Rome.

Chapin, A. 2007. “Boys Will Be Boys: Youth and Gender Identity in the Theran Frescoes.” In A. Cohen and J. Rutter, eds., 229–55.

Cohen, A. and J. Rutter, eds. 2007. Constructions of Childhood in Ancient Greece and Italy. Princeton.

Collon, D. 1994. “Bull-Leaping in Syria.” Ägypten und Levante 4: 81–8.

Coulomb, J. 1981. “Les boxeurs minoens.” Bulletin de correspondance hellénique 105: 27–40.

Crouwel, J. 1981. Chariots and Other Means of Land Transport in Bronze Age Greece. Amsterdam.

Crouwel, J. 1991. Well-Built Mycenae: The Mycenaean Pictorial Pottery (fasc. 21). Warminster, UK.

Crouwel, J. 2006. “Late Mycenaean Pictorial Pottery.” In D. Evely, ed., 233–55.

Damiani Indelicato, S. 1988. “Were Cretan Girls Playing at Bull-Leaping?” Cretan Studies 1: 39–47.

Darcque, P. and J.-C. Poursat, eds. 1985. L’iconographie minoenne. Athens.

Davis, E. 1977. The Vapheio Cups and Aegean Gold and Silver Ware. New York.

Davis, E. 1987. “The Knossos Miniature Frescoes and the Function of the Central Courts.” In R. Hägg and N. Marinatos, eds., 157–61.

Decker, W. 1987. “Die mykenische Herkunft des griechischen Totenagons.” In T. Eberhard, ed., 201–30.

Deger-Jalkotzy, S. and I. Lemos, eds. 2006. Ancient Greece: From the Mycenaean Palaces to the Age of Homer. Edinburgh.

Demakopoulou, K. 1989. “Contests in the Bronze Age Aegean: Crete, Thera and Mycenaean Greece.” In O. Tzachou-Alexandri, ed., 25–30, 111–25.

Dickinson, O. 2009. “Social Development in the Postpalatial Period in the Aegean.” In E. Borgna and P. Càssola Guida, eds., 11–19.

Doumas, C. 1992. The Wall-Paintings of Thera. Athens.

Eberhard, T., ed. 1987. Forschungen zur ägäischen Vorgeschichte: Das Ende der mykenischen Welt. Berlin.

Evans, A. 1930. The Palace of Minos. Vol. 3. London.

Evely, D., ed. 2006. Lefkandi IV: The Bronze Age, The Late Helladic IIIC Settlement at Xeropolis. London.

French, E. and K. A. Wardle, eds. 1988. Problems in Greek Prehistory. Bristol.

Golden, M. 1998. Sport and Society in Ancient Greece. Cambridge.

Güntner, W. 2000. Tiryns XII: Figürlich bemalte mykenische Keramik aus Tiryns. Mainz.

Hägg, R. and N. Marinatos, eds. 1987. The Function of the Minoan Palaces. Stockholm.

Hallager, B. P. and E. Hallager. 1995. “The Knossian Bull: Political Propaganda in Neopalatial Crete?” In R. Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier, eds., 2: 547–56.

Hamilakis, Y., ed. 2002. Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking “Minoan” Archaeology. Oxford.

Hood, S. 1978. The Arts in Prehistoric Greece. Harmondsworth, UK.

Immerwahr, S. 1985. “A Possible Influence of Egyptian Art in the Creation of Minoan Wall Painting.” In P. Darcque and J.-C. Poursat, eds., 41–50.

Immerwahr, S. 1990. Aegean Painting in the Bronze Age. University Park, PA.

Kilian, K. 1980. “Zur Darstellung eines Wagenrennens aus spätmykenischer Zeit.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Athenische Abteilung 95: 21–31.

Kilian-Dirlmeier, I. 1993. Die Schwerter in Griechenland (ausserhalb der Peloponnes), Bulgarien, und Albanien. Stuttgart.

Koehl, R. 2000. “The Ritual Context.” In J. A. MacGillivray, J. Driessen, and L. H. Sackett, eds., 131–43.

Koehl, R. 2006. Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta. Philadelphia.

Konsolaki-Yiannopoulou, E. 2003a. “Ta mykenaïka eidolia apo ton Agio Konstantino Methanon.” In E. Konsolaki-Yiannopoulou, ed., 375–406.

Konsolaki-Yiannopoulou, E., ed. 2003b. Argosaronikos: Praktika 1ou Diethnous Synedriou Istorias kai Archaiologias tou Argosaronikou. A’: E Proïstorike Periodos. Athens.

Krzyszkowska, O. 2005. Aegean Seals: An Introduction. London.

Kyle, D. 2007. Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, MA.

Laffineur, R. and W.-D. Niemeier, eds. 1995. Politeia: Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age. 2 vols. Liège/Austin.

Lapatin, K. 2001. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Oxford.

La Rosa, V., D. Palermo, and L. Vagnetti, eds. 1999. Epi Ponton Plazomenoi: Simposio italiano di studi egei dedicato a Luigi Bernabò Brea e Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli. Rome.

Laser, S. 1987. Sport und Spiel. Göttingen.

Lebessi, A., P. Muhly, and G. Papasavvas. 2004. “The Runner’s Ring: A Minoan Athlete’s Dedication at the Syme Sanctuary, Crete.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung 119: 1–31.

MacGillivray, J. A., J. Driessen, and L. H. Sackett, eds. 2000. The Palaikastro Kouros: A Minoan Chryselephantine Statuette and Its Aegean Bronze Age Context. London.

Maran, J. 2006. “Coming to Terms with the Past: Ideology and Power in Late Helladic IIIC.” In S. Deger-Jalkotzy and I. Lemos, eds., 123–50.

Marinatos, N. 1989. “The Bull as an Adversary: Some Observations on Bull-Hunting and Bull-Leaping.” Ariadne 5: 23–32.

Marinatos, N. 1993. Minoan Religion: Ritual, Image, and Symbol. Columbia, SC.

Marinatos, N. 1994. “The ‘Export’ Significance of Minoan Bull Hunting and Bull Leaping Scenes.” Ägypten und Levante 4: 89–93.

Marinatos, N. 2007. “Bull-Leaping and Royal Ideology.” In M. Bietak, N. Marinatos, C. Palivou, et al., eds., 127–32.

Marinatos, N. and C. Palivou. 2007. “The Taureador Frescoes from Knossos: A New Study.” In M. Bietak, N. Marinatos, C. Palivou, et al., eds., 115–26.

Militello, P. 2003. “Il rhyton dei Lottatori e le scene di combattimento: battaglie, duelli, agoni e competizioni nella Creta neopalaziale.” Creta Antica 4: 359–401.

Miller, S. 2004. Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven.

Mommsen, H. and J. Maran. 2000/1. “Production Places of Some Mycenaean Pictorial Vessels: The Contribution of Chemical Pottery Analysis.” Opuscula Atheniensia 25/6: 95–106.

Morenz, L. 2000. “Stierspringen und die Sitte des Stierspieles im altmediterranen Raum.” Ägypten und Levante 10: 195–203.

Morgan, L. 1995. “Of Animals and Men: The Symbolic Parallel.” In C. Morris, ed., 171–84.

Morris, C., ed. 1995. Klados: Essays in Honour of J. N. Coldstream. London.

Mylonopoulos, J. and H. Roeder, eds. 2006. Archäologie und Ritual: Auf der Suche nach der rituellen Handlung in den antiken Kulturen Ägyptens und Griechenlands. Vienna.

Panagiotopoulos, D. 2006. “Das minoische Stierspringen. Zur Performanz und Darstellung eines altägäischen Rituals.” In J. Mylonopoulos and H. Roeder, eds., 125–38.

Pelon, O. 1985. “L’acrobat de Malia et l’art de l’époque proto-palatiale en Crète.” In P. Darcque and J.-C. Poursat, eds., 35–40.

Rutter, J. 1992. “Cultural Novelties in the Post-Palatial Aegean World: Indices of Vitality or Decline?” In W. Ward and M. Joukowsky, eds., 61–78.

Rystedt, E. 1986. “The Foot-Race and Other Athletic Contests in the Mycenaean World.” Opuscula Atheniensia 16: 103–16.

Rystedt, E. 1988. “Mycenaean Runners – including Apobatai.” In E. French and K. A. Wardle, eds., 437–42.

Säflund, G. 1987. “The Agoge of the Minoan Youth as Reflected by Palatial Iconography.” In R. Hägg and N. Marinatos, eds., 227–33.

Sakellarakis, J. 1992. The Mycenaean Pictorial Style in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Athens.

Scanlon, T. 1999. “Women, Bull Sports, Cults and Initiation in Minoan Crete.” Nikephoros 12: 33–70.

Shaw, M. 1995. “Bull Leaping Frescoes at Knossos and Their Influence on the Tell el-Dab’a Murals.” Ägypten und Levante 5: 91–120.

Shaw, M. 1996. “The Bull-Leaping Fresco from below the Ramp House at Mycenae: A Study in Iconography and Artistic Transmission.” Annual of the British School at Athens 91: 167–90.

Sipahi, T. 2001. “New Evidence from Anatolia Regarding Bull-Leaping Scenes in the Art of the Aegean and the Near East.” Anatolica 27: 107–26.

Taracha, P. 2002. “Bull-Leaping on a Hittite Vase. New Light on Anatolian and Minoan Religion.” Archaeologica Warsawa 53: 7–20.

Tzachou-Alexandri, O., ed. 1989. Mind and Body: Athletic Contests in Ancient Greece. Athens.

van Wijngaarden, G. J. 2002. Use and Appreciation of Mycenaean Pottery in the Levant, Cyprus and Italy (1600–1200 bc). Amsterdam.

Vermeule, E. and V. Karageorghis. 1982. Mycenaean Pictorial Vase Painting. Cambridge, MA.

Ward, W. and M. Joukowsky eds. 1992. The Crisis Years: The 12th Century B.C.: From beyond the Danube to the Tigris. Dubuque, IA.

Warren, P. 1969. Minoan Stone Vases. London.

Younger, J. 1976. “Bronze Age Representations of Aegean Bull-Leaping.” American Journal of Archaeology 80: 125–37.

Younger, J. 1995. “Bronze Age Representations of Aegean Bull-Games, III.” In R. Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier, eds., 2, 507–45.

Zuckerman, S., D. Ben-Shlomo, P. Mountjoy, et al. 2010. “A Provenance Study of Mycenaean Pottery from Northern Israel.” Journal of Archaeological Science 37: 409–16.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

Summaries of the evidence for Minoan and Mycenaean sport are often included in the early chapters of books presenting general histories of Greek sport (e.g., Miller 2004: 20–30; Kyle 2007: 38–53). Most of the scholarship on Bronze Age Aegean sport, however, takes the form of specialized periodical literature or papers published in the proceedings of academic conferences, much of it in languages other than English (mostly modern Greek, Italian, German, and French). In view of the purely pictorial nature of the evidence, most treatments of prehistoric Aegean sport are closely connected with the description and analysis either of specific artistic media (e.g., painting or small-scale carving) or else of individual works of art.

In English, a useful overall introduction to Aegean art of the third and second millennia BCE is Hood 1978. For wall painting, see Immerwahr 1990; for seals and signet rings, Krzyszkowska 2005; for stone vases, Warren 1969; for vase painting, Vermeule and Karageorghis 1982, supplemented by more focused works authored by Crouwel (1991, 2006) and Sakellarakis 1992. For bull-related sports, the best places to begin are the essays by Younger (1976, 1995), supplemented by works on the most relevant frescoes written by Shaw (1995, 1996) and collected in Bietak, Marinatos, Palivou, et al. 2007. For boxing, the most useful titles in English are Koehl’s 2006 book on rhyta and Chapin’s helpful 2007 conference paper on how to assess the age of youthful males in Aegean art. Chariot racing is best investigated through Crouwel’s definitive 1981 study of Aegean chariotry. Whether or not running and spear throwing were formal sporting pursuits of the Mycenaeans is explored by Rystedt (1986, 1988).

A full-length treatment of all aspects of Aegean Bronze Age sport that takes cognizance of the constantly growing body of pictorial evidence now at our disposal and at the same time pays appropriate attention to significant chronological shifts and cultural differences within the multiethnic environment represented by the Aegean world in the second millennium BCE has yet to be written.