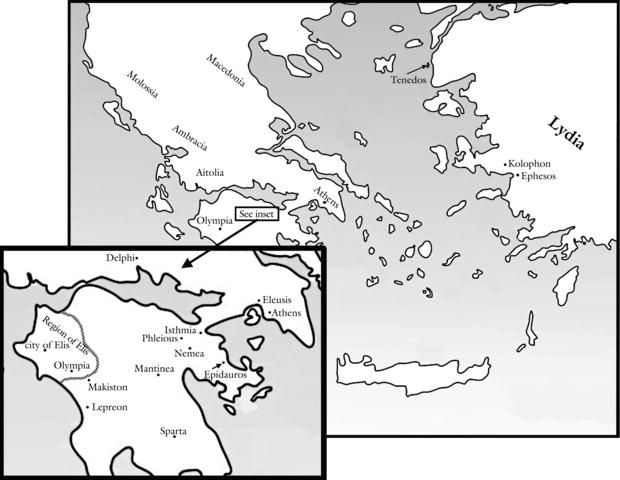

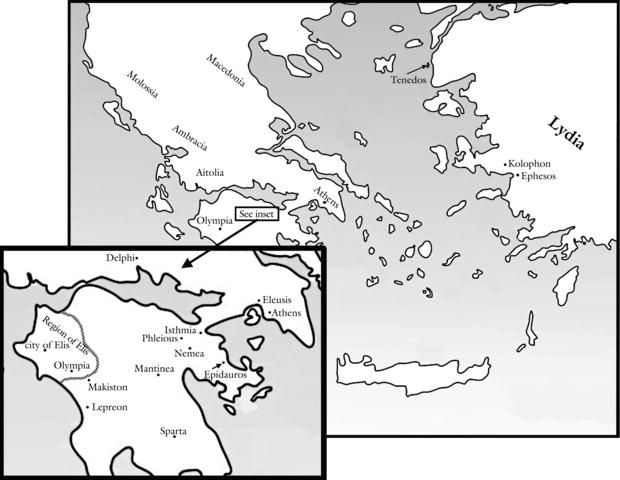

Map 8.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

Among the defining hallmarks of ancient Greek culture were an extraordinary devotion to sport, a powerful competitive ethos, and the importance of the city-state as a key form of sociopolitical organization. All of these were present in a particularly clear form at Olympia, and the results of their complicated interaction there are among the best illustrations of some of the most important facets of ancient Greek history and of the workings of Greek city-state culture.

Olympia was frequented by massive numbers of Greeks from all over the far-flung Greek world. In this respect, Olympia was a Panhellenic sanctuary in the same way as Delphi. But Olympia was in fact an extra-urban sanctuary of the large city-state of Elis, which arranged and administered the competitions and made its control of the site clear to all (see Map 8.1 for the locations of key sites mentioned in this essay). It was perhaps inevitable that this state of affairs should on occasion generate criticism of Elis for partiality, but in fact Elis’s administration of the Olympics seems to have been on the whole reasonably impartial. The general atmosphere at Olympia, however, was highly politicized, and the competitions were conceived of not only as competitions between athletes, but also as competitions between city-states that identified strongly with their athletes.

Map 8.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

Scholars customarily describe Olympia as a “Panhellenic” (literally “all-Greek”) sanctuary, and it will be useful to begin by briefly explaining what this means, though it should be emphasized that Olympia was far from being alone in having the qualities that may justify the appellation:

Olympia, then, is described as Panhellenic because its competitions were open to all Greeks and because the site itself and its competitions were of such immense prestige as to attract athletes and dedicants from afar. Also, the athletic program at Olympia can be said to have been Panhellenic in the sense that the athletic events at Olympia were practiced all over the Greek world (Young 2004: 24).

Scholars frequently use the term “Panhellenism” to refer to an ancient ideological position that developed in the fifth century and reached its full formulation in the fourth century. Proponents of Panhellenism held that the Greek city-states should end their internal rivalries and wars, unite under the dual hegemony of Athens and Sparta, and wage a war of vengeance and enrichment against the ostensibly weak and effeminate Persians. The basis on which this ideology was constructed was “the notion of Hellenic ethnic identity and the concomitant polarization of Greek and barbarian as generic opposites, which rapidly developed as a result of the Persian invasion [of the early fifth century]” (Flower 2000: 65; see also Mitchell 2007).

Certain features of the way the Olympics and Greek sports were practiced could be construed to reinforce this polarization between Greeks and barbarians as well as other tenets of Panhellenism. For example, the nudity of Greek athletes was constructed as an ethnic boundary marker since public nudity was unthinkable for high-status males among neighboring ethnic groups such as the Lydians and Persians (Nielsen 2007: 22–8; for more on Greek athletic nudity, see Chapter 13, which includes an excursus on this subject). Moreover, certain proponents of Panhellenism addressed the huge crowds assembled at Olympia during the festival and lectured on Panhellenism in the ideological sense. The orator Gorgias gave a full-blown Panhellenist oration in 408, and 20 years later Lysias followed suit, attributing to Herakles a Panhellenist motive for founding the Olympics (namely that the festival would promote friendship among the Greeks) (Flower 2000: 92–3).

However, Olympia was never the site of any sort of institutions that might have helped turn the ideology of Panhellenism into reality. The authorities in charge of Olympia did not provide a forum for making decisions after or for acting on crusading speeches such as those of Gorgias and Lysias (Roy 2013). Panhellenist speeches at Olympia were expressions of purely personal points of view, and none of those speeches seem to have eventuated in action. Neither did the magistrates in charge of Olympia attempt to extend the “sacred truce” to cover the whole Greek world. The truce protected only the territory of Elis itself and travelers to the festival and thus resembled truces proclaimed not only for the protection of the three other festivals of the periodos, but also by many other city-states for the protection of lesser, local festivals. To mention just a few examples in the Peloponnese itself, “sacred truces” were proclaimed by the communities of Makiston (Strabo 8.3.13), Mantinea (Xenophon Hellenika 5.2.2), and Phleious (Xenophon Hellenika 4.2.16).

Furthermore, the Olympic authorities seem to have taken an inclusive rather than an exclusive view of who was a Greek, and there is no known instance of an athlete denied admission on account of his ethnic identity. In the fourth century, kings of Macedonia (Philip II, see Moretti 1957: nos. 434, 439, 445) and Molossia (Arrhybas, see Moretti 1957: no. 450) competed at Olympia;2 both Macedonia and Molossia were located on the geographic fringes of the Greek homeland, and the Greek ethnicity of their inhabitants was at least occasionally questioned by residents of more centrally located communities such as Athens. In the Hellenistic period, citizens of newly founded Greco-Macedonian city-states competed (e.g., Apollonius of Alexandria in Egypt (Moretti 1957: no. 512)) as well as Greeks from recently Hellenized areas such as Syria (e.g., Asklepiades of Sidon (Moretti 1957: no. 724)). In later centuries, at least some Roman citizens competed (e.g., Gnaeus Marcius (Moretti 1957: nos. 743 and 745)). (For further discussion of Greek sport in Egypt after the Macedonian conquest, see Chapter 23. For further discussion of Panhellenism at Olympia and Delphi, see Chapter 19.) Panhellenism thus operated within circumscribed boundaries at Olympia.

Large numbers of Greeks from many different communities frequented the sanctuary at Olympia. Precise numbers for the crowds that assembled to attend and participate in the Olympics are unavailable, but an audience of some forty-five thousand seems a reasonable estimate (Nielsen 2007: 55–7). However, the sanctuary was administered by a single city-state, Elis, situated some 60 kilometers to the north of Olympia by road (36 kilometers as the crow flies). The celebration of the Olympics was preceded by a procession from Elis to Olympia (Lee 2001: 28–9; Nielsen 2007: 47). Under normal circumstances, Elis alone controlled admission to the sanctuary and the competitions, it alone laid down the rules under which the competitions were conducted, and it appointed all the personnel of the sanctuary from among its own citizens.

Before each celebration of the Olympics, Elis sent sacred ambassadors on tours of the Greek world to announce the upcoming festival and proclaim the Olympic truce; in this way Elis itself actively promoted the international profile of the Olympics. The sacred ambassadors were styled spondophoroi (“truce bearers”) or theoroi (“sacred envoys”), and at least from the mid-fifth century they were assisted at their destinations by members of the local elite who had been appointed theorodokoi (“receivers of theoroi”) by Elis and served as links between the theoroi and the local political authorities. Since the evidence for this Olympic epangelia (“announcing”) by Elis is exiguous, the places definitely known to have been visited by Eleian theoroi are limited to Sparta, the region of Aitolia, and the island of Tenedos, but it may reasonably be assumed that practically all of the widespread Hellenic world was so visited (Perlman 2000: 63–6; Nielsen 2007: 39–40, 62–8).

The Olympic truce banned violence against travelers going to the Olympics and protected the territory of Elis against military aggression (Lämmer 1975/6 and 2010; Dillon 1995; Hornblower and Morgan 2007b: 30–3). Elis itself was the sole judge in determining whether a given city-state had respected it, as is clear from a famous incident in connection with the Olympics of 420. In that year, the Eleians excluded Sparta from the Olympic festival and its citizens from the competitions because the Spartans, according to the Eleians, had broken the Olympic truce by sending a military force into the small city-state of Lepreon in order to assist it in a conflict against Elis. At the time of the Spartan expedition in support of Lepreon the truce had been proclaimed at Elis but not yet at Sparta. Even so, the Eleians held a hearing under Olympic law, and the case was conducted and heard by Eleians only. The Spartans were not even present at the hearing, at which they were fined the substantial sum of two minai3 for each soldier sent into Lepreon. When the Spartans refused to pay the fine, the Eleians excluded them from the Olympics, that is, “from the sacrifice and the competitions” (Thucydides 5.49.1–50.4, with Roy 1998 and Nielsen 2005: 67–74).

What an ancient athlete needed, accordingly, in order to “qualify” for the Olympics, was permission to participate from the Eleian magistrates, and this permission could be denied. In 420, when Elis had condemned Sparta for breaching the Olympic truce, a Spartan aristocrat named Lichas could not enter his team of horses under his own name, but he registered it as a collective entry of the Thebans (Nielsen 2007: 83 n. 293). An athlete, then, had to belong to a political community that had accepted and respected the Olympic truce in order to be allowed to compete in the Olympics.

There were other requirements that athletes had to meet (Crowther 2004: 23–33), and for each celebration of the Olympics Elis appointed a (new) board of Hellanodikai (“Judges of the Greeks”) whose duty it was, among other things, to enforce these requirements. Elis’s way of appointing the Hellanodikai must have been subject to change over time, but at least in the middle of the fourth century they were selected, perhaps by lot (Romano 2007: 98), one from each of the “tribes” or subdivisions of the Eleian citizen body (Roy 2006), in the same way that the Athenian athlothetai, who were responsible for the Panathenaic Games, were appointed ([Aristotle] Constitution of the Athenians 60.1). The Hellanodikai, clearly, were civic magistrates of the city-state of Elis despite their name, which may have been Elis’s way of highlighting the fact that the Olympics attracted competitors from all over the Greek world.4 Pausanias, writing in the second century CE, states that the Hellanodikai were appointed 10 months prior to the celebration of the Olympics and received instruction from the nomophylakes (“Guardians of the Laws”) of Elis, who educated them in the niceties of their duties (Pausanias 6.24.3; cf. Crowther 2004: 72; Sinn 2004: 89; Romano 2007: 100). There is no reason to believe that these arrangements were substantively different in the Classical and Hellenistic periods.

The Hellanodikai decided whether a given competitor would be admitted to or excluded from participation in the Olympics. Athletes could be excluded on a number of grounds, such as if their city-state of origin had violated the sacred truce, if they could not produce evidence of Greek extraction, or if they were too young to compete (Nielsen 2007: 18–21). At the Olympics competitors were divided into two age-groups, “boys” and “men.” Such age-grouping was standard procedure in Greek athletics though not all festivals used the same groupings (see Chapter 14). At the Panathenaic Games, for example, there were three age-groups: “boys,” “beardless,” and “men.” At Olympia, competitors between the ages of 12 and 18 seem to have been classed as boys and those above 18 as men (Crowther 2004: 87–92).

Exactly how the Hellanodikai decided whether an entrant should be admitted and to which age class is unknown but, in the case of boys, physical development seems to have been taken into account (Crowther 2004: 91–2). In addition, the Hellanodikai may have interviewed the boys and their attendants, for they had to swear an oath that they would decide fairly, would not take bribes, and would not disclose information about individual athletes (Pausanias 5.24.10). This stipulation of confidentiality was probably designed “to preserve the integrity of the youth categories” (Perry 2007: 85), and it, or something like it, probably existed from an early period. In 468, the Hellanodikai excluded Pherias of Aigina from the competitions as being too young (Pausanias 6.14.1; Pherias went on to win the boys’ wrestling at the Olympics of 464 (Moretti 1957: no. 255)). Also in the fifth century, Nikasylos of Rhodes was refused admittance to the boys’ wrestling and placed in the men’s class, which he won (Pausanias 6.14.2; Moretti 1957: no. 973). Such decisions by the Hellanodikai seem to have been final, but on at least one occasion, outsiders attempted to bring some pressure to bear on the Hellanodikai in order to influence their decisions. Xenophon relates that King Agesilaos of Sparta attempted to use his personal influence in order to have an Athenian boy, who was exceptionally big, admitted to the boys’ stadion, since the boy in question had a homoerotic relationship with someone closely connected to Agesilaos (Hellenika 4.1.40; cf. Plutarch Agesilaos 13.4 and Shipley 1997: 190–3).5

Other duties of the Hellanodikai included the refereeing of the competitions and here again their decisions seem to have been final. They could fine athletes for breaking the rules and punish both athletes and spectators by flogging if they so wished (Crowther and Frass 1998). The Spartan Lichas, who, as already explained, was unable to enter his equestrian team under his own name in 420, entered it in the name of Thebes. When his chariot was victorious, he stepped into the arena in order to crown the charioteer “wishing to make clear that the chariot belonged to him” (Thucydides 5.50.4). For this de facto violation of the official formalities of participation the Olympic authorities had him flogged and driven away (cf. Xenophon Hellenika 3.2.21).

Elis’s control of the sanctuary was visibly emphasized in other ways as well:

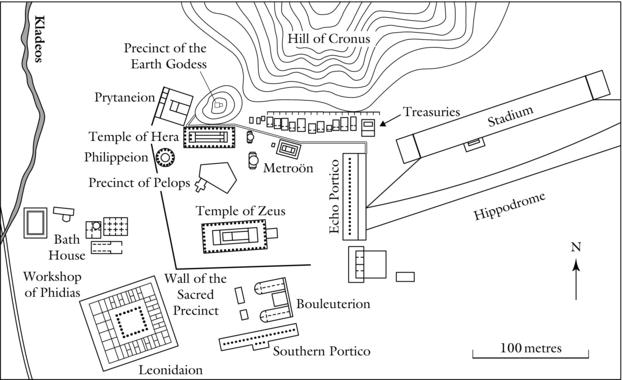

Map 8.2 Plan of the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia and surrounding areas.

Olympia, then, was a Panhellenic sanctuary in the sense that it was visited by massive numbers of Greeks from all over the Greek world, while also serving as a key religious and political center for the city-state of Elis. It was perhaps inevitable that, as a result, conflicts of interest should arise. A (quite possibly fictional) anecdote in Herodotus (2.160) seems to reflect non-Eleian criticism of partiality in Elis’s administration of the Olympics. The story goes that the Eleians in the early sixth century sent an embassy to Psammis II of Egypt (ruled 595–589) and challenged the wise Egyptians to suggest improvements in the fairness of their handling of the Olympics, all the while being convinced that this would be impossible. It has been plausibly suggested that this anecdote was originally an Eleian fabrication designed to justify the quality of Elis’s administration of the Olympics by having the universally recognized wisdom of the Egyptians endorse its fairness (Asheri, Lloyd, Corcella, et al. 2007: 360). Herodotus’s retelling, however, reflects a later version of the story in which the message has been turned upside down. Upon hearing that citizens of Elis were allowed to compete in the Olympics, the Egyptians stated that this was a wholly unfair arrangement “since it was impossible not to favor a fellow citizen who entered the competitions, thereby committing wrong to a foreigner.” It seems a reasonable assumption that the story as transmitted by Herodotus reflects Greek discontent with the predominant position of Elis in the running of the Olympics and is in fact a sarcastic remark on the title of the chief officials at the Olympics, “the Judges of the Greeks” (Hellanodikai).6

In general, it seems that Eleian competitors in the Olympics won more than their due share of victories, Elis being the most successful city-state throughout Olympic history and conspicuously so in the boys’ competitions and the equestrian events (Crowther 2004: 99–113). This, however, need not necessarily be the result of partiality on the part of the Hellanodikai. Particularly in the boys’ contests and the equestrian events, proximity to the contest site must have been a great asset, and it is noteworthy that in the highly prestigious events such as the men’s stadion and the four-horse chariot race Eleians fared much less well.

One instance of what seems to be flagrant partiality on the part of the Hellanodikai in favor of a compatriot, however, is recorded by Pausanias (6.3.7). At the Olympics of 396, two of the three Hellanodikai officiating at the men’s stadion declared Eupolemos of Elis the winner, while the third pronounced Leon of Ambracia the victor. Leon proceeded to lodge a complaint with the Olympic Council (Olympike boule), and the Council sentenced the two Hellanodikai in question to a fine. However, their decision as to the outcome of the race was not overruled, and Eupolemos passed into history as victor in the men’s stadion (Moretti 1957: no. 367). The decisions of the Hellanodikai, then, seem to have been final, even when officially acknowledged to have been wrong.

On present evidence, however, the “scandal” of 396 is unique and though there are, as we have seen, various indications that the Hellanodikai were on occasion criticized for partiality, they seem in general to have acted fairly and responsibly throughout Olympic history. Elis, moreover, was ready to alter rules that could reasonably be described as unfair. Thus, when Troilos of Elis won an equestrian victory in 372 while serving as one of the Hellanodikai, it must have become clear that “to judge a fellow judge…tested even the most impartial officials” (Crowther 2004: 79). The Eleians then passed a law to the effect that in the future no citizen acting as one of the Hellanodikai could enter horses for the equestrian competitions at the Olympics (Pausanias 6.1.5).

The best testimony to the overall quality of Eleian administration of the Olympics, however, comes from the Spartans. During the Peloponnesian War (431–404), the Spartans came to harbor several serious grudges against the Eleians, who had defected from the Peloponnesian League and allied themselves with Sparta’s enemies, excluded the Spartans from the Olympics of 420, humiliated the Spartan aristocrat Lichas by having him flogged during these same Olympics, and debarred the Spartan king Agis from sacrificing at Olympia. All these acts were serious blemishes to Spartan prestige (Xenophon Hellenika 3.2.21–2). After their victory in the Peloponnesian War the Spartans decided to settle their score with Elis (Roy 2009b), a goal which they accomplished by invading Elis and forcibly breaking up the Eleians’ local alliances by means of which the Eleians controlled a considerable amount of territory (on the local alliances of Elis, see Roy 2008 and 2009a). Among the conditions for peace that the Spartans contemplated, according to Xenophon (Hellenika 3.2.31), was that the Eleians be deprived of their administration of Olympia and hand it over to (unnamed) local rival claimants. However, the Spartans did not in fact abolish Eleian administration of Olympia. Since they had what must have seemed to them perfectly good reasons, why did they abstain? They did so, according to Xenophon, “because they considered the rival claimants to be rustics [choritai] and not capable of presiding over the sanctuary” (3.2.31). Evidently the Spartans did not find the rival claimants to be in possession of the administrative sophistication needed for such an important job, and so they resolved to leave Olympia in the hands of the experienced Eleians. In a situation, then, in which it could be reasonably expected that Elis would no longer deploy its administration of Olympia against Sparta, the Spartans found Eleian administration of the sanctuary to be preferable to what would in effect have been their own administration. The overall quality of Elis’s administration of Olympia must, therefore, have been high.

The Eleians’ impartiality did not, however, mean that Olympia was an apolitical environment. On the contrary, athletics at Olympia took place in what can only be described as a highly politicized context in which athletes were thought of as representing not only themselves, but also their city-states. Perceived offenses against individual athletes, accordingly, often ended up as the concern of their home states. The flogging of Lichas is a case in point and provided Sparta with a casus belli against Elis. Another example is provided by an affair involving the Athenian pentathlete Kallippos. In 322, Kallippos was victorious at Olympia, but was fined by the Hellanodikai for bribing his opponents. The Athenian government intervened in the matter and sent the great orator Hypereides to Elis to have the fine lifted. When the Eleians refused to do so, the Athenians in their turn refused to pay and proceeded to boycott the Olympics for a period of perhaps as much as 20 years (Weiler 1991; Habicht 1997: 19–20).

Greek city-states took great interest in the performance of “their” athletes at Olympia and often celebrated their victories in extravagant ways. Thus, when Exainetos from the city of Akragas in Sicily returned home in 412 after his second victory in the stadion, he was escorted into the city by 300 chariots drawn by white horses (Diodorus Siculus 13.82.7; Nielsen 2007: 95). At Athens, Olympic victors received the right to dine daily in the prytaneion, probably the greatest honor the Athenian city-state had to bestow (Inscriptiones Graecae I3 131; Nielsen 2007: 94–5). At Ephesos, victors in Panhellenic athletic contests were proclaimed in the agora (city center/marketplace) and received a cash payment (Inschriften von Ephesos 1415); some city-states even set up sculptures of their victors in their agora (Lycurgus Against Leokrates 51).

In Olympia itself, the victors received not only a crown of leaves from the sacred olive tree, but also the right to erect a sculpture commemorating their victory (Raschke 1988b; Herrmann 1988; Lattimore 1988; Smith 2007). By Pausanias’s day, several hundred such statues stood at Olympia on inscribed bases that identified the athlete, his feats, and his home city, which shared in the glory created by the victories achieved by its athletes. At least by the Late Classical period city-states had begun to finance not only the commemorative victor monuments erected at home but on occasion also the monument erected at Olympia. Thus, in the 320s the city-state of Kolophon in Asia Minor celebrated an Olympic victory in wrestling by one of its citizens with a sculpture at Olympia as well as one in its own territory (Pausanias 6.17.4; Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 35.1125; Catling and Kavanou 2007 and 2008).

For a Greek athlete, there was no greater achievement than an Olympic victory (see, for example, Plato Republic 465d–e), and it seems reasonable to assume that an athlete’s primary personal motive for entering the Olympics will have been to achieve the immense glory created by victory at the most prestigious contest of all (Nielsen forthcoming). Pindar opens his Eighth Olympian by stating that an Olympic victory brings “great and eternal glory indeed.” But what took place at Olympia was about much more than a relatively small group of athletes testing their relative talents. Olympia was a Panhellenic center of prime importance, while also functioning as an extra-urban sanctuary of the city-state of Elis. This created a highly politicized atmosphere rife with tensions, in spite of the Eleians’ generally competent and evenhanded management of the sanctuary. The sources of those tensions and how they were played out over the centuries provide invaluable insight into the Greeks’ devotion to sport, competition, and the city-state. Indeed, one might argue that the Olympics offer a unique illustration of the working of Greek city-state culture and that it is impossible to write the history of ancient Greece without paying close attention to the Olympics.

NOTES

1 All dates are BCE unless otherwise indicated.

2 Note also that Philip was allowed to erect at Olympia a monument, the Philippeion, to commemorate his victory at the Battle of Chaironeia in 338. On this monument, see Schultz 2007 and 2009.

3 Two minai equals 200 drachmai, one drachma being roughly a day’s pay for an average worker in the second half of the fifth century.

4 For other possible explanations of the title Hellanodikai, see Siewert 1992: 115 and Nielsen 2007: 20–1.

5 On a similar note, it was claimed that Alcibiades of Athens was able to arrange certain matters to suit his personal purposes at Olympia in 416 owing to his influence with the Hellanodikai ([Andocides] 4.26).

6 On Herodotus’s literary aims in presenting the story, see Dorati 1998.

REFERENCES

Asheri, D., A. Lloyd, A. Corcella, et al. 2007. A Commentary on Herodotus: Books I–IV. Oxford.

Bandy, S., ed. 1988. Coroebus Triumphs: The Alliance of Sport and the Arts. San Diego.

Catling, R. and N. Kanavou. 2007. “Hermesianax the Olympic Victor and Goneus the Ambassador: A Late Classical–Early Hellenistic Family from Kolophon.” Epigraphica Anatolica 40: 59–66.

Catling, R. and N. Kanavou. 2008. “Hikesios Son of Lykinos of Kolophon, Victor in the Boys Wrestling at Olympia, and Pausanias VI 17.4.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 165: 109–10.

Colvin, S. 2007. “Review of Sophie Minon, Les Inscriptions éléennes dialectales (V–II siècle avant J.-C.), Volume I.” Bryn Mawr Classical Review 11.07.

Coulson, W. and H. Kyrieleis, eds. 1992. Proceedings of an International Symposium on the Olympic Games, 5–7 September 1988. Athens.

Crowther, N. 2003. “Elis and Olympia: City, Sanctuary and Politics.” In D. Phillips and D. Pritchard, eds., 61–74.

Crowther, N. 2004. Athletika: Studies on the Olympic Games and Greek Athletics. Hildesheim.

Crowther, N. and M. Frass. 1998. “Flogging as a Punishment in the Ancient Games.” Nikephoros 11: 51–82.

Dillon, M. 1995. “Phrynon of Rhamnous and the Macedonian Pirates: The Political Significance of Sacred Truces.” Historia 44: 250–4.

Dorati, M. 1998. “Un giudizio degli Egiziani sui giochi olimpici: (Hdt. II 160).” Nikephoros 11: 9–20.

Finley, M. and H. W. Pleket. 1976. The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years. London.

Flower, M. 2000. “From Simonides to Isocrates: The Fifth-Century Origins of Fourth-Century Panhellenism.” Classical Antiquity 19: 65–101.

Funke, P. 2005. “Die Nabel der Welt. Überlegungen zur Kanonisierung der ‘panhellenischen’ Heiligtümer.” In T. Schmitt, W. Schmitz, A. Winterling, et al., eds., 1–16.

Funke, P. and M. Haake, eds. 2013. Greek Federal States and Their Sanctuaries: Identity and Integration. Stuttgart.

Habicht, C. 1997. Athens from Alexander to Antony. Cambridge, MA.

Hansen, M. H. 2006. Polis: An Introduction to the Ancient Greek City-State. Oxford.

Hansen, M. H. and T. Fischer-Hansen. 1994. “Monumental Political Architecture in Archaic and Classical Greek Poleis: Evidence and Historical Significance.” In D. Whitehead, ed., 23–90.

Herrmann, H.-V. 1974. “Zanes.” Pauly-Wissowa Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft Supplement 14: 977–81.

Herrmann, H.-V. 1988. “Die Siegerstatuen von Olympia.” Nikephoros 1: 119–83.

Hodkinson, S., ed. 2009. Sparta: Comparative Approaches. Swansea.

Hornblower, S. and C. Morgan, eds. 2007a. Pindar’s Poetry, Patrons, and Festivals: From Archaic Greece to the Roman Empire. Oxford.

Hornblower, S. and C. Morgan. 2007b. “Introduction.” In S. Hornblower and C. Morgan, eds., 1–43.

International Congress of Peloponnesian Studies, ed. 2006. Praktika tou 7th Diethnous Synedriou Peloponnesiakon Spoudon. 4 vols. Athens.

Jensen, J., G. Hinge, P. Schultz, et al., eds. 2009. Aspects of Ancient Greek Cult: Context, Ritual and Iconography. Aarhus.

König, J., ed. 2010. Greek Athletics. Edinburgh.

Lämmer, M. 1975/6. “The Nature and Function of the Olympic Truce in Ancient Greece.” History of Physical Education and Sport 3: 37–52.

Lämmer, M. 2010. “The So-Called Olympic Peace in Ancient Greece.” In J. König, ed., 39–60.

Lattimore, S. 1988. “The Nature of Early Greek Victor Statues.” In S. Bandy, ed., 245–56.

Lee, H. M. 2001. The Program and Schedule of the Ancient Olympic Games. Hildesheim.

Lombardo, M., ed. 2008. Forme sovrapoleiche e interpoleiche di organizzazione nel mondo greco antico. Galatina.

Miller, S. 1978. The Prytaneion: Its Function and Architectural Form. Berkeley.

Miller, S. 2004. Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven.

Minon, S. 2007. Les inscriptions éléennes dialectales (Vie–IIe siècle avant J.-C.). 2 vols. Geneva.

Mitchell, L. 2007. Panhellenism and the Barbarian in Archaic and Classical Greece. Swansea.

Moretti, L. 1957. Olympionikai: i vincitori negli antichi agoni olimpici. Rome.

Nielsen, T. H. 2005. “A Polis as Part of a Larger Identity Group: Glimpses from the History of Lepreon.” Classica et Mediaevalia 56: 57–89.

Nielsen, T. H. 2007. Olympia and the Classical Hellenic City-State Culture. Copenhagen.

Nielsen, T. H. Forthcoming. “An Essay on the Extent and Significance of the Greek Athletic Culture in the Classical Period.” Proceedings of the Danish Institute at Athens.

Perlman, P. 2000. City and Sanctuary in Ancient Greek: The Theorodokia in the Peloponnese. Göttingen.

Perry, J. S. 2007. “‘An Olympic Victory Must Not be Bought’: Oath-Taking, Cheating, and Women in Greek Athletics.” In A. Sommerstein and J. Fletcher, eds., 81–8.

Phillips, D. and D. Pritchard, eds. 2003. Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World. Swansea.

Raschke, W., ed. 1988a. The Archaeology of the Olympics: The Olympic and Other Festivals in Antiquity. Madison.

Raschke, W. 1988b. “Images of Victory: Some New Considerations of Athletic Monuments.” In W. Raschke, ed., 38–54.

Rizakis, A., ed. 1991. Achaia und Elis in der Antike. Athens.

Romano, D. 2007. “Judges and Judging at the Ancient Olympic Games.” In G. Schaus and S. Wenn, eds., 95–113.

Roy, J. 1998. “Thucydides 5.49.1–50.4: The Quarrel between Elis and Sparta in 420 B.C., and Elis’ Exploitation of Olympia.” Klio 80: 360–8.

Roy, J. 2006. “Pausanias 5.9.6: The Number of Hellanodikai at Elis in 364 B.C.” In International Congress of Peloponnesian Studies, ed. 1: 225–32.

Roy, J. 2008. “The Nature and Extent of Eleian Power in the Western Peloponnese.” In M. Lombardo, ed., 293–306.

Roy, J. 2009a. “Hegemonial Structures in Late Archaic and Early Classical Elis and Sparta.” In S. Hodkinson, ed., 69–88.

Roy, J. 2009b. “The Spartan–Eleian War of c.400.” Athenaeum 97: 69–86.

Roy, J. 2013. "Olympia, Identity, and Integration: Elis, Eleia, and Hellas." In P. Funke and M. Haake, eds., 107–21.

Schaus, G. and S. Wenn, eds. 2007. Onward to the Olympics: Historical Perspectives on the Olympic Games. Waterloo, ON.

Schmitt, T., W. Schmitz, A. Winterling, et al., eds. 2005. Gegenwärtige Antike, antike Gegenwarten: Kolloquium zum 60. Geburtstag von Rolf Rilinger. Munich.

Schultz, P. 2007. “Leochares’ Argead Portraits in the Philippeion.” In P. Schultz and R. von den Hoff, eds., 205–33.

Schultz, P. 2009. “Divine Images and Royal Ideology in the Philippeion.” In J. Jensen, G. Hinge, P. Schultz, et al., eds., 205–33.

Schultz, P. and R. von den Hoff, eds. 2007. Early Hellenistic Portraiture: Image, Style, Context. Cambridge.

Sève, M. 1993. “Les Concours d’Épidaure.” Revue des études grecques 106: 303–28.

Shipley, D. 1997. A Commentary on Plutarch’s Life of Agesilaos. Oxford.

Siewert, P. 1992. “The Olympic Rules.” In W. Coulson and H. Kyrieleis, eds., 113–17.

Sinn, U. 2004. Das antike Olympia: Götter, Spiel und Kunst. 2nd ed. Munich.

Smith, B. 2007. “Pindar, Athletes, and the Early Greek Statue Habit.” In S. Hornblower and C. Morgan, eds., 83–139.

Sommerstein, A. and J. Fletcher, eds. 2007. Horkos: The Oath in Greek Society. Exeter, UK.

Spivey, N. 2004. The Ancient Olympics. Oxford.

Weiler, I. 1991. “Korruption in der olympischen Agonostik und die diplomatische Mission des Hypereides in Elis.” In A. Rizakis, ed., 87–93.

Whitehead, D., ed. 1994. From Political Architecture to Stephanus Byzantius: Sources for the Ancient Greek Polis. Stuttgart.

Young, D. 2004. A Brief History of the Olympic Games. Oxford.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

A classic introduction to the ancient Olympics is provided by Finley and Pleket 1976, which is, however, without references. The best modern introduction is Miller’s reconstruction of the celebration of the festival in 300 BCE (2004: 113–28). Other introductions to the same material can be found in Young 2004 and Spivey 2004; for a more detailed study, see Sinn 2004. The basic discussion of the Olympic sacred truce can be found in Lämmer 2010.

A study of the Olympics and the sanctuary at Olympia as a focal point for the negotiation of the different layers of Greek identity is found in Nielsen 2007; Roy 2013 covers some of the same ground. A brief description the city-state of Elis as the host of the Olympics is found in Crowther 2003. Elis’s exploitation of Olympia to further its own local power politics is discussed by Roy 1998 and Nielsen 2005. The general context in which the political aspects of the Olympics must be seen is set out in Hansen 2006.