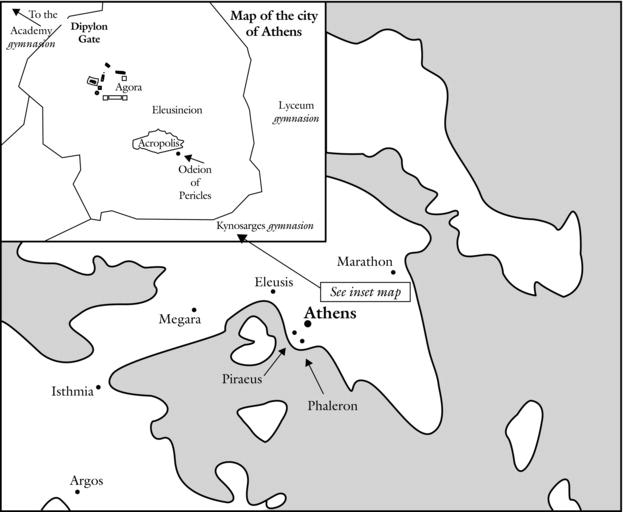

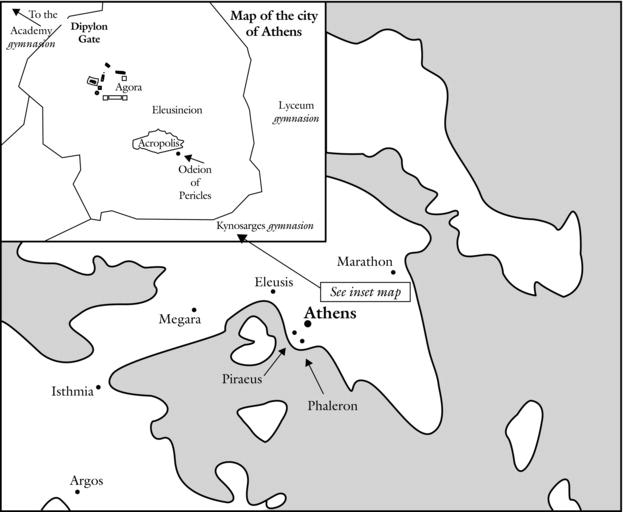

Map 10.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

According to Thucydides, in the winter of 431/0,1 early in the Peloponnesian War, Pericles delivered a famous speech in which he praised Athens for, among many other things, the recreations it offered its citizens. He described those recreations as the “various contests [agones] and sacrifices spread throughout the year” and lauded their capacity to refresh the Athenians’ spirits (Thucydides 2.38.1). In 380 the orator and educator Isocrates wrote another speech of the same type. He praised Athens for its tradition of great festal assemblies; its numerous sporting and artistic entertainments, with enthusiastic competitors and multitudes of spectators from all over the Greek world; and its varied contests that rewarded speed, strength, eloquence, wisdom, and other talents. For such contests Athens gave the “greatest prizes [athla megista],” and, while festivals elsewhere in Greece took place at long intervals and were soon over, Athens held festal assemblies throughout every year (Panegyricus 43–6). Although rhetorical, these passages properly highlight the prominence and variety of sport and spectacle in Athens.

This essay on sport in Athens in the Archaic (700–480) and Classical (480–323) periods has three major parts. The first part surveys the phenomenon of Athenian sport, especially in the Panathenaic (“all-Athenian”) Games. The second part contextualizes Athens within a broader debate on the social history (the social origins, status, and social mobility) of Greek athletes. The third part offers an extended discussion of the sociopolitical dimensions of Athenian sport history. The sources for Athens are significantly more abundant than for any other ancient Greek community, and, as a result, Athens provides our best opportunity to examine the role and influence of sport in the sociopolitical history of a Greek city-state.

Overall, by focusing on Athens, I hope to contribute to ongoing discussions about whether sport remained elitist or became more broadly accessible over time, and whether sport in Greek city-states intensified or mitigated sociopolitical tensions. I suggest that socioeconomic changes did make Athenian athletic participation somewhat more accessible, although family finances remained a crucial factor, and that, despite tensions, sport in Athens was a positive, popular, and vital element in civic life.

The earliest evidence for Athenian athletics comes from scenes of boxers and chariots on pottery from the eighth century. During that period Athenian elites probably participated in local, privately organized funeral games that offered material prizes and local cult festivals that included footraces (see Chapter 3 in this volume). By the seventh century Athenians turn up as Olympic victors (Kyle 1987: 20), and in the sixth century Athens began to reward its athletes for victories at Panhellenic contests.

In 566/5 Athens expanded an earlier festival to Athena into what became its grandest festival, the Panathenaia. This festival was held annually, and was timed to coincide with and celebrate the start of the year, which in Athens began in July. The Panathenaia was celebrated with special magnificence every fourth year, so that there were two different versions of the Panathenaia, the Greater and the Lesser. Inscriptions dating to c.560 from the Acropolis that mention a dromos (a racecourse or a race) and an agon (a contest) administered by a board of civic officials (hieropoioi) probably refer to the Panathenaic Games (Raubitschek 1949: nos. 326–8).

Lasting several days, the Greater Panathenaia included a religious procession through the city and up to the Acropolis, a sacrifice of 100 cattle and distribution of the meat for feasting, the presentation of a special robe (peplos) to the cult statue of the goddess Athena, and a varied program of contests. (See Map 10.1 for the locations of key sites mentioned in this essay.) The Lesser Panathenaia featured a procession and some contests (Shear 2003a: 171–2; Tracy 2007), but the contests at the Greater Panathenaia (usually called the Panathenaic Games in modern scholarship), became Athens’s sporting showplace for the wider Greek world and the most prominent of the many “local” or “civic” athletic festivals (i.e., athletic festivals held in or near a city, with extensive official state involvement) organized by various Greek communities.2

Victors at the Panathenaic Games received prizes that declared and advertised Athens’s wealth and honored its patron goddess. In the 560 s Athens began offering prizes of sacred olive oil in distinctively shaped and decorated “Panathenaic prize amphorae.” These vases were decorated with an armed Athena on the front and athletic scenes on the back. The front also bore an official prize inscription: “One of the prizes from Athens” (ton Athenethen athlon) (see Chapter 5 for more on Panathenaic amphorae). Neither stingy nor shy, Athens handed out at least 1,400 and probably over 2,000 Panathenaic amphorae as prizes each time the Panathenaic Games were held. Each amphora contained about 10 gallons of olive oil. In myth, Athena had given Athens the gift of an olive tree, and olive oil was one of Athens’s most famous exports.

Map 10.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

Elaborate games with valuable prizes were an investment in marketing and an inducement for visitors. The poet Pindar, in an ode for a Panathenaic victor from Argos, mentions prizes of oil in painted vessels (Nemean 10.33–7). Non-Athenian victors transported amphorae widely, from Italy to the Black Sea, broadcasting Athens’s fame as a grand and divinely favored community.

Scholars have attempted to reconstruct the development of the program of events at the Panathenaic Games in the sixth and fifth centuries, using literary references and depictions on Panathenaic amphorae. The program, apparently already quite extensive in the sixth century, changed and expanded over time. Athens borrowed elements from Olympia and probably Delphi (Neils 2007), but it did not merely copy existing contests elsewhere in Greece.3

Fragments of an inscribed prize list (Inscriptiones Graecae II2 2311) from the year 380 provide invaluable evidence for the program of events, which included team as well as individual contests in multiple age classes as well as prizes for second place. Some special events were for Athenians only, but musical events and many Olympic-style gymnic contests ( gymnikoi agones) and hippic contests (hippikoi agones) were open to all Greeks. (For basic information about gymnic and hippic competitions at Greek athletic contests, see Chapter 1.) The information contained in this inscription about the events that were held and the prizes on offer for each event is summarized in tabular form here (based on the reconstruction in Shear 2003b, which should also be consulted on the date of the inscription). In the interests of clarity, that information is broken up into five separate tables, with each table pertaining to specific sections of the inscription and reflecting section headings found in the original text. The inscription is damaged, as a result of which there are numerous gaps in those tables.

Table 10.1 List of gymnic contests at the Panathenaic Games.

| Event | First place | Second place |

| Number of amphorae awarded | ||

| Boys | ||

| Dolichos | 30 | 6 |

| Stadion | 50 | 10 |

| Pentathlon | 30 | 6 |

| Wrestling | 30 | 6 |

| Boxing | 30 | 6 |

| Pankration | 40 | 8 |

| Youths | ||

| Stadion | 60 | 12 |

| Pentathlon | 40 | 8 |

| Wrestling | 40 | 8 |

| Boxing | 40 | 8 |

| Pankration | 50 | 10 |

| Men | ||

| Dolichos | 60 | 12 |

| Stadion | 80 | 16 |

| Diaulos | 60 | 12 |

| Pentathlon | ? | ? |

| Wrestling | ? | ? |

| Boxing | ? | ? |

| Pankration | 70 | 14 |

| Hoplitodromos | 70 | 14 |

After gold and silver crowns for musical victors, the inscription lists numbers of amphorae of oil awarded as first and second prizes (at a 5 : 1 ratio) in the gymnic events, which were open to Athenians and non-Athenians alike, for three age categories (boys, youths, men) (see Table 10.1).

Next come hippic events, starting with the intriguing apobates race, open only to Athenian citizens, with an uncertain numbers of jars of oil for first and second prizes (see Table 10.2). Strongly associated with Athena and held on the Panathenaic Way in the marketplace (the agora), this spectacular chariot race involved soldiers in armor dismounting and (probably) remounting speeding chariots (Schultz 2007) (see Figure 10.1). Perhaps evoking epic warfare, in which Homeric heroes descended from chariots to fight at Troy, the event is immortalized in the sculptured frieze on the Parthenon (Neils 2001: 138–41; Neils and Schultz 2012). The following entries in the list pertain to hippic contests open to all, with relatively rich prizes on offer. Whereas the victor in the men’s stadion (a sprint down the track) received 80 vases, victory in the zeugos (a race with a pair of equids yoked to a cart or sulky) for adult horses brought 140 amphorae. Numbers for the prestigious four-horse chariot races must have been larger still.

Table 10.2 List of hippic contests at the Panathenaic Games.

| Hippic contests open only to Athenian citizens | First place | Second place |

| Number of amphorae awarded | ||

| Apobates | ? | ? |

| Hippic contests open to all | First place | Second place |

| Number of amphorae awarded | ||

| Horse race | ? | ? |

| Four-colt chariot race | ? | ? |

| Four-horse chariot race | ? | ? |

| Two-colt chariot race | ? | ? |

| Two-horse chariot race | ? | ? |

| Colt zeugos | 40 | 8 |

| Horse zeugos | 140 | 40 |

Specified as reserved “for warriors” and probably reflecting Athens’s increased use of cavalry in recent decades, the next listings are four special events open only to Athenian cavalrymen, with prizes for first and second place: horse race, zeugos with horses, the processional zeugos (the details of which remain mysterious), and the javelin throw from horseback (see Table 10.3).

Listed next, with oxen as prizes, are four events that were closed to non-Athenians, the contestants consisting of teams entered by each of the 10 tribes into which Athenian citizenry was divided (see Table 10.4).4 First comes pyrrhic dance, which in myth was invented by Athena to celebrate the defeat of the Giants. Groups of dancers, known as choruses (one chorus from each tribe in each of three different age classes and hence 30 choruses in total), equipped with shields, helmets, and spears, imitated defensive and offensive movements (Plato Laws 815a).5 Euandria, the contest in “manly excellence,” revolved around the display of size, strength, and training (Crowther 2004: 330–9; Neils 1994: 154–9). The handsome and fit winners were the first carriers of sacred objects in the Panathenaic procession. Torch races, popular spectacles combining ritual and athletics, took place as part of the Panathenaia and various other festivals (Bentz 2007). The Panathenaic event was a relay race in which the winning team had to arrive first with its torch lit (Pausanias 1.30.2; see Aristophanes Frogs 1087–98 for an amusing description). Apparently 10 runners per tribe covered a distance of over 2,500 meters from the Academy gymnasion to the Acropolis (Fisher 2011: 189–90). The prize for the individual victor probably went to the runner who ran the final leg of the race for the winning team. The “contest of ships” (probably a boat race) with three placements and oxen for prizes, first attested in this inscription, perhaps existed earlier to recognize sailors for assisting Athens’s security and success, or to increase popular participation in the games.

Figure 10.1 Marble relief found in the Athenian Agora showing apobates race, fourth century BCE, Agora Museum S399. Source: Photograph by Steven Bach. Used with permission.

Table 10.3 List of contests “for warriors” at the Panathenaic Games.

| Event | First place | Second place |

| Number of amphorae awarded | ||

| Horse race | 16 | 4 |

| Horse zeugos | 30 | 6 |

| Processional zeugos | 4 | 1 |

| Javelin from horseback | 5 | 1 |

The final two sections of the inscription as preserved (both covered in Table 10.5) concern the anthippasia, a competitive riding display by two groups of cavalrymen (with each group consisting of men from 5 of the 10 tribal cavalry units), and cyclic choruses, another form of group dancing.6

Table 10.4 List of tribal contests at the Panathenaic Games.

| Event | Prize |

| Boys’ pyrrhic dance | 1 ox (worth 100 drachmai) |

| Youths’ pyrrhic dance | 1 ox |

| Men’s pyrrhic dance | 1 ox |

| Contest in manly excellence (euandria) | 1 ox |

| Torch race | Winning tribe: 1 ox Individual victor: 1 hydria (a vase worth 30 drachmai) |

| Boat race | 1st place: 3 oxen 2nd place: 2 oxen 3rd place: 1 ox |

Table 10.5 Prizes for the anthippasia and cyclic choruses at the Panathenaic Games.

| Event | Prize |

| Anthippasia | 1st place: ? 2nd place: ? 3rd place: ? |

| Men’s cyclic chorus | 1st place: ? 2nd place: ? |

| Boys’ cyclic chorus | 1st place: ? 2nd place: ? |

With its many contestants, multiple performances and rituals, and finally the great procession, the Panathenaia was a sacred and spectacular display of unity, power, and piety.7 The games celebrated and glorified the city and its goddess, attracted visitors, and satisfied the agonistic inclinations of the Athenians, directly, by (individual or group) competition and, vicariously, by spectatorship.

Musical, dramatic, and athletic competitions, as well as torch races, choral dancing contests and displays, and more obscure contests, permeated the Athenian calendar of festivals (Kyle 1987: 40–8; Osborne 1993, especially Table 16.1). An elitist conservative, the so-called Old Oligarch, probably writing in the late fifth century, complains, anonymously, that Athens had more festivals than other states (Constitution of the Athenians 3.2).8 Although it is impossible to provide a comprehensive review of all such festivals here, it is worth briefly discussing some of the more important Athenian festivals, other than the Panathenaia, that included athletic contests.

Ostensibly founded by the mythical Athenian hero Theseus, the Oschophoria included a ritual race by 20 youths (2 from each of the 10 tribes) bearing vine branches from the Temple of Dionysus in the city of Athens to the seacoast at Phaleron, with a prize consisting of a special drink called the “fivefold” (pentaploa). In the fifth century the Epitaphia (likely founded in 479) included public funeral games for Athens’s war dead with “games of strength, knowledge, and wealth” (Lysias Epitaphios 2.80) – probably gymnic, musical, and hippic contests. The Bendideia, held in honor of the Thracian goddess Bendis and introduced in 429/8 (Plato Republic 327a–8a), featured evening torch races on horseback. The Olympieia, the first evidence for which dates to the fourth century, featured Athens’s cavalry forces and included an anthippasia contest.

Athens developed a policy of integrating lesser and local cults into the state festival calendar and redirecting them to give them a civic focus and appeal. Athletic contests held at Eleusis (from the sixth century on), and the Herakleia festival at Marathon (from c.490), became centralized under Athenian administration. (Eleusis and Marathon were located on the western and eastern limits of Athenian territory, respectively.) The centralizing policy also applied to the hero cult of Theseus and its games (founded c.470).

Scholarly debate about the extent of nonelite access to gymnic athletic contests (participation in hippic contests required large-scale expenditures and remained the preserve of the elite) has been lively and is ongoing. This section summarizes scholarly positions on the issues in general and with particular application to Athens. Gardiner’s (1930) traditional scenario of early noble amateurs being driven out of sport by lower class professionals misrepresented history from selected bits of literature, but went unchallenged for decades. Pleket (1975) disputed Gardiner’s notion of amateurism and asserted the early predominance and the enduring presence of elites in athletics, while accepting that in later periods a certain number of athletes came from non-elite families. Young (1984) also challenged Gardiner on amateurism, and he aggressively argued, against Pleket, that significant numbers of lower class athletes existed from the earliest days of organized athletics.

There now seem to be three schools of thought in regard to elite and nonelite participation in Greek sport. One school accepts increased access over time with socioeconomic changes, but doubts extensive democratization or egalitarianism in athletics in the Archaic and Classical periods. Pleket (1975, 2001, 2005) defends and reasserts his views based on epigraphical evidence. His use of abundant inscriptional evidence from a broad array of times and places in the Greek world counterbalances a tendency of some scholars to keep turning to the same limited number of problematic literary references (e.g., Old Oligarch Constitution of the Athenians 1.13, 2.10; Euripides Autolykos Fragment 282; Isocrates 16.33). My study of Athenian athletics and athletes (Kyle 1987; also see Kyle 1997), following Pleket but focused on one city-state, argues that sport in Archaic and Classical Athens enhanced civic consciousness and pride, and that although participation remained somewhat elitist in practice, broader socioeconomic changes at Athens aided a significant shift from an elitism of birth to one of wealth (with the increase of the middle class and nouveaux riches). Golden (1998: 141–75; 2008: 1–39) interprets Greek sport in general as a realm of social differentiation, and concerning Athens he suggests tensions and divisiveness between dominant and emerging classes, between hippic and gymnic competition, and between conservative and democratic agendas: “Athletic competition was ruled by an elitist or at least meritocratic mindset even in democratic Athens” (2008: 26).

A second school of thought is championed by Pritchard (2003, 2009, 2013), who contends that athletic participation was not accessible to poor or nonwealthy families because of the expense of training in privately financed classes taught by paidotribai (athletic tutors). According to Pritchard, even in the fifth and fourth centuries, when Athens had a strongly democratic sociopolitical system, “athletics remained an exclusive pursuit of the wealthy” (2003: 332; cf. 2009: 229). He further suggests that, although excluded, lower class Athenians enthusiastically supported the athletic practices of their social superiors because, as rowers in the navy who contributed physically and militarily to the state, they associated themselves ideologically with militaristic agonistic virtues (e.g., training, effort, risk, and excellence (arete)) traditionally ascribed to the higher classes and embodied in successful athletes. A common athletic and military culture with positive notions of effort, value, and virtue spanned the classes and assisted social cohesion.

The third school of thought asserts widespread democratization and popular participation. Miller (2000, 2004: 232–4) suggests that nudity, objective judging criteria, and the practice of flogging for infractions in Greek sport made athletes equals, reduced social tensions, and fostered democracy. Recent works that discuss Athens have emphasized meritocratic factors: valuable Panathenaic prizes, state-sponsored tribal team and dancing competitions, state rewards for Panhellenic victories, free access to three public gymnasia, numerous wrestling schools (palaistrai) and hired trainers, and greater financial resources and improved social mobility in general. Fisher (1998, 2011) argues, especially concerning torch races, that team events (financially subsidized annually by numerous wealthy citizens as an obligatory public service) provided opportunities for thousands of nonelite participants. He also suggests that pederastically motivated wealthier Athenians supported young athletes of lesser status. In effect, Fisher revives Young’s notion (1984, e.g., concerning Croton) that athletic subsidization by the state – and also by personal arrangements – provided the resources needed by aspiring athletes from less-than-wealthy families.

Supporting Fisher’s arguments, and integrating modern sport sociology, Christesen (2007, 2012) asserts a positive reciprocal relationship among meritocracy, democracy, and “mass sport” (broad participation and spectatorship) as they emerged in sixth- and fifth-century Greece. Sociopolitical circumstances affected sport, but sport also positively affected the functioning of society through socialization, the reinforcement of proper social relations, and consensus among groups. Against Pritchard, he argues that a full education (including an athletic tutor for a boy of 7–15 years) was affordable for Athenian families of middling or modest wealth, if not the poor, and he points out that Athens had more gymnasia and training facilities than those needed by a small number of rich citizens. Like Fisher, he feels tribal competitions, especially in dancing in groups, dramatically increased participation in sport at Athens. Ironically but perhaps significantly, Pritchard and Christesen agree that sport assisted social order in democratic Athens, either by shared ideology or meritocracy.

Debate continues because scholars disagree about (1) terms (sport, athletics, elite); (2) factors (prizes, financial support in group events, nudity, pederasty); (3) costs (of private preparation and travel); (4) likelihood of profitable careers; and (5) numbers, duration, and intensity of participation in team events and dancing versus individual Olympic-style gymnic contests. Ultimately, while social historical studies and sociological models are useful, our evidence, even for Athens, has limitations.

While I agree that meritocratic factors, in tribal team events in particular, made sport more accessible, especially if we include group dancing, I still suggest an “elitism of wealth” (of family financial resources) with respect to individual participation in organized competitions. Sending one’s sons from an early age to an athletic tutor and participation in sport and dancing were socially desirable for status display, but they were not mandatory for all Athenian citizens. Roughly half the Athenian citizen male population belonged to a “working class” without adequate leisure time or the financial resources to pay for athletic training, let alone serious athletic competition. Of course, an exceptionally talented individual might succeed in some events, but that would not have been common. Moreover, basic training under an athletic tutor was a necessary but insufficient precondition for competitive participation in individual gymnic events at chrematitic games that awarded valuable prizes; successful participation in such games required extensive and expensive training and leisure time. Youths of the upper and middle class were thus more likely than poor Athenians to participate in individual events at organized competitions at all levels, but especially in high-level competitions such as the Panathenaic Games and the Olympics.

In Archaic and Classical Athens sport was a public, highly contested realm of social and political ambitions. Early groups and leaders appreciated that victory at home or at major games abroad brought them public recognition and status validation. Over time, however, as the remaining sections of this essay will show, there were dramatic social and economic changes as Athens became more wealthy, populous, and democratic. Increased meritocracy (fair access and judging based on athletic merit) in sport, and democratization (broader participation and popular sovereignty) in politics, expanded sporting activity in popular public performances. Local gymnasia provided prestigious, high profile forums for sociopolitical display, and political leaders patronized and administered games, facilities, and rewards as political capital to promote themselves and their agendas.

Not without tension but generally in a positive way, the shared experiences of competing and spectating at athletic festivals (re)formed the Athenian community, communicating and reinforcing – or contesting – sociopolitical values and order (see König 2009: 379–85 on spectatorship and festivals as representations of community). The growth of sport pleased the citizens, trumpeted the fame of Athens, and encouraged civic harmony and pride.

Seventh-century Athens knew sporting rivalries and political tensions largely within the aristocratic class, as noble families strove for honor and influence – to be the elite of the elite. They probably competed in local games, but their main focus, consistent with the ideology of building prestige and networks beyond their polis (city-state), was on games outside of Athens. Competition at elaborate funeral games and at Olympia affirmed social status. Of Athens’s first Olympic victor, Pantakles in 696, we know only that he was a sprinter, but Athenian victors at major games abroad probably were from wealthy, politically active, aristocratic families. Phrynon, the Olympic pankration victor in 636, was probably the same Phrynon who became a general and a founder of colonies. Kylon, the rich son-in-law of the tyrant of Megara, won the Olympic diaulos in 640 and later made an ill-fated attempt to become a tyrant at Athens. (For testimonia on Athenian athletes mentioned here, see Kyle 1987: 102–23, 195–228.)

In the early years of the sixth century, the Athenian statesman Solon enacted political reforms that made wealth, rather than birth, the basis for eligibility to hold high office, and his reform of the popular assembly and courts, along with his economic policies, increased sociopolitical access and mobility for much of Athens’s populace. Solon also legislated monetary rewards for Athenian victors in Panhellenic athletic contests: 500 drachmai for an Olympic victory – estimated by Young (2004: 98) as roughly equivalent to US$700,000 – and 100 drachmai for an Isthmian victory. He probably did this to encourage Athenians to see athletics, as well as politics, as a civic and not a private matter (Kyle 1984, but cf. Mann 2001: 70–81).

In the 560 s, amid increasingly virulent political factionalism, some leader or group in Athens opportunistically promoted the Panathenaia as a forum for ceremony, competition, and recreation. Unfortunately, the sources are too scanty to achieve any degree of certainty as to who was responsible for what innovations (see Kyle 1987: 22–31; Anderson 2003: 67–76; Neils 2007).

The long tyranny of Peisistratos and his sons Hippias and Hipparchos (561–510) threatened aristocrats’ athletic dominance. The tyrants, rather typically, were civic boosters who sought popular support through public projects and entertainments. Fostering civic athletics to please the people and to dissipate tensions, they made a concerted effort to promote the cult of Athena. The Peisistratids are associated with embellishing the Panathenaic Way and holding contests in the agora, including contests in rhapsodic recitations of Homer. Hipparchos is credited with a costly wall around the Academy gymnasion, within which Peisistratos dedicated an altar to Eros (on Athenian athletic facilities, see Kyle 1987: 56–101). The tyrants actively sponsored the Panathenaic festival and its contests; Hippias was organizing the Panathenaic procession when Hipparchos was assassinated in 514 (Phillips 2003: 204–8).

Like most tyrants, Peisistratos drove other aristocrats out of Athens, allowing some to return only through their concessions to his power. Hardly idle, notable families still publicized themselves as victors and patrons. When Kimon, a member of a wealthy and powerful Athenian family, won his second Olympic victory in the four-horse chariot race in 532, he had Peisistratos declared the official victor, and the tyrant let him return to Athens from exile (Herodotus 6.103). Peisistratos clearly enjoyed the prestige of being an Olympic victor. When Kimon won a third time in 528, however, he was killed at Athens, arguably because Peisistratos’s sons resented his high profile (Connor 1971: 10–11; Kyle 1987: 111–12, 158).

After Spartan military intervention brought about the end of the Peisistratid tyranny in 510, the Athenian citizenry rejected a Spartan-backed conservative regime and in 508, under the leadership of a reformer named Kleisthenes, established a relatively egalitarian and democratic sociopolitical system that entailed the formation of 10 new tribes as basic subdivisions of the Athenian populace (Thorley 2004: 22–50). An aristocrat from a famous horse-racing family, Kleisthenes understood the political usefulness of sport, and scholars associate the addition or expansion of tribal contests at the Panathenaic Games with the Kleisthenic reforms (Neils 1994; Fisher 2011: 179–82). Tribal team events certainly promoted middle-class participation in sport as well as stronger bonds between Athenians and their tribes.

Fifth-century Athenian sport history unfolded in the context of a long-running military conflict between Athens and Persia, in which Athenian success was initially derived from the skill of its infantrymen, who typically came from relatively wealthy families, but that more and more came to depend on its navy, which was manned largely by rowers from poorer families. As Athens became more affluent, meritocratic, and democratic, emerging groups emulated the sporting pastimes of the privileged classes, competing in gymnic and tribal events, and exercising nude in the gymnasia. Some of these new athletes seem to have come from wealthy but nonaristocratic families (Kyle 1987: 113–19). Kallias, son of Didymias (not to be confused with a homonymous Athenian victor in the hippic events at the Olympic and Pythian Games from an aristocratic clan who was active in the first half of the sixth century) won the pankration at Olympia in 472, as well as at Isthmia, Nemea, and Delphi, and also in the Panathenaia. This Kallias did not come from an aristocratic clan and may later have been active politically in opposition to Pericles, for he seems to have been in danger of being ostracized (Kyle 1987: 161). Another pankratiast, Autolykos, a Panathenaic victor in 421/0, and his father, Lykon, were conspicuous and reasonably wealthy men, but not from an aristocratic clan (Kyle 1987: 114, 117, 161).

As the democracy strengthened, aspiring statesmen tended to avoid demanding personal gymnic competition as a means to public exposure and influence and instead approached athletics indirectly, as benefactors. Recognizing the political value of fostering games for their careers, for social order and civic consciousness, and also for military preparedness on land and at sea, generals such as Kimon and Pericles dispensed popular patronage and expanded opportunities and facilities for leisure and sport. Kimon (born c.510, died 450, a descendant of the Kimon mentioned earlier) used his private wealth to beautify Athens’s recreational areas, planting shade trees in the agora, and embellishing the Academy gymnasion with water channels, shade trees, and tracks for running (Plutarch Kimon 13.7; Kyle 1987: 73–4). Kimon’s rival Pericles (born c.495, died 429) made Athens even more democratic than it had been when he came to power, and he actively promoted festivals and contests. During his long, influential career he expanded tribal military events (e.g., pyrrhic, cavalry, and boat contests). In 442 he was an athlothetes, one of the officials who organized the Panathenaic festival, and he probably built the Odeion in the agora as a venue for musical contests around the same time (Plutarch Pericles 13.5). He also seems to have been responsible for a renovation of the Lyceum gymnasion and for the renewal of the practice of awarding of a free meal daily in the town hall to Athenian Panhellenic victors (Kyle 1987: 79, 145–7).

Pericles’ policies on sport incited some limited criticism. (On critics of sport, see Kyle 1987: 124–41 and Chapter 21 in this volume.) The so-called Old Oligarch complains that the poor enjoy, while the rich pay for, festivals and contests, that Athens’s athletically inept masses want frequent festivals and sacrifices with meat distributions, and that greed moved them to participate in singing, running, and dancing contests (Constitution of the Athenians 1.13, 2.9). He also suggests (2.10) that while some wealthy people have private sports facilities, commoners have built more public facilities, which they use more than the wealthy do. Grudgingly he concedes that the people had the power, and that oligarchic disagreement mattered little.

Alcibiades, Pericles’ ward, sought a quick and easy route to power and, to that end, in 416 went to Olympia seeking fame. Entering seven chariots, he was placed first, second, and (third or) fourth, and his extravagant socializing at Olympia attracted attention and controversy back in Athens (Golden 1998: 169–71; Kyle 2007: 172–3; Papakonstantinou 2003). In his speech encouraging the Athenians to invade Sicily in 415, Alcibiades boasted that his Olympic success conveyed honor and power, for which Athens should be grateful (Thucydides 6.16.2). An Olympic victor only by means of wealth, he nonetheless declared himself superior to his fellow citizens, who then approved his plans for Sicily. Roughly two decades later, Isocrates argued that Alcibiades could have competed bodily but chose not to because he knew that “some athletes” were lower class, ill-educated, and from “lesser states” (a point aimed at Athenian nationalism?), so he chose chariot competition as “undeniably a matter of wealth” (16.33). Isocrates’ words suggest the presence of nonelite athletes in gymnic sport in some number (beyond Athens?), but they also conveniently excuse Alcibiades from arduous gymnic training, which would have delayed his political ambitions.9

After its defeat in the Peloponnesian War (431–404), Athens’s athletic program continued and probably expanded. We know of several fourth-century Athenian athletes, especially in running and combat sports; some seem to be from recently wealthy families, while the backgrounds of others are obscure. The career of Dioxippos, an Olympic pankration victor who accompanied Alexander the Great (Kyle 1987: 119–20, 150–1), and the accusation of bribery at Olympia against the pentathlete Kallippos in 322 (Kyle 1987: 119–20), may indicate that financial or occupational “professionalism” was not far off. Competition seems to have been a personal matter of status display, and sport increasingly involved educational and military training.

Sport and politics were realms of contestation at Athens, and there were tensions and negotiations as athletic programs and participation grew. Athenian sport and politics became more meritocratic and democratic in theory than in practice, but overall, sport – especially at the Great Panathenaia – was a positive, integrating factor in Athenian society. Hugh Lee has noted that “even as sport asserts or reinforces differences, it can also promote a discourse of unity. The wonder of Greek sport is that it somehow forged divergent social classes and quarrelsome city-states into a Pan-Hellenic community, which fostered and celebrated athletic arete” (1999: 400–1). Athens’s famous festivals, athletes, diverse contests, and rich prizes inspired civic pride and promoted the state as a political community. Pericles, Isocrates, and the Old Oligarch too, were right about the popularity of athletic festivals as cherished celebrations of democratic Athens.

NOTES

1 All dates are BCE unless otherwise indicated.

2 Civic athletic festivals were typically chrematitic, which is to say that they offered victors valuable prizes. The great Panhellenic athletic festivals such as the Olympic Games were stephanitic, which is to say that they offered only wreaths as prizes. (Hence they are sometimes also called crown or sacred-crown games.) For more on the difference between stephanitic and chrematitic games, see Chapters 1 and 23 in this volume and Remijsen 2011. The early Panathenaic Games were not classified as stephanitic, but sixth-century vase paintings show officials at the Panathenaic Games crowning victors with wreaths; see Valavanis 1990.

3 On the program of events at the Panathenaic Games, see Johnston 1987; Kyle 1987: 178–94; Kyle 1992: 82–97; Neils 1992b: 14–17; Bentz 1998: 11–22; Neils and Tracy 2003: 13–27; Shear 2003a and b.

4 On Athenian tribes, see Thorley 2004: 19–26.

5 For details on pyrrhic dancing, see Ceccarelli 2004.

6 On the anthippasia, see Camp 1998: 28–33. For details on cyclic choruses, see Goette 2007: 117, 122–3.

7 For the depiction of the Panathenaia on the Parthenon frieze, see Neils 1996a and Neils 2001.

8 This treatise was erroneously ascribed to the Athenian author Xenophon and sometimes appears in modern publications of Xenophon’s work. For an English translation, see Marr and Rhodes 2008.

9 Alcibiades was a gymnasiarch (on which see Pleket’s essay on inscriptions, Chapter 6) and was involved in legislation regarding the Kynosarges gymnasion (Isocrates 16.35; Athenaeus 234e; Inscriptiones Graecae I3 134; Pritchard 2009: 213).

REFERENCES

Anderson, G. 2003. The Athenian Experiment: Building an Imagined Political Community in Ancient Attica, 508–490 b.c. Ann Arbor.

Bentz, M. 1998. Panathenäische Preisamphoren: Eine athenische Vasengattung und ihre Funktion vom 6.–4. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Basel.

Bentz, M. 2007. “Torch Race and Vase Painting.” In O. Palagia and A. Choremi-Spetsieri, eds., 73–80.

Boys-Stones, G., B. Graziosi, and P. Vasunia, eds. 2009. The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies. Oxford.

Camp, J. M. 1998. Horses and Horsemanship in the Athenian Agora. Athens.

Cartledge, P., P. Millett, and S. von Reden, eds. 1998. Kosmos: Essays in Order, Conflict and Community in Classical Athens. Cambridge.

Ceccarelli, P. 2004. “Dancing the Pyrrihichê in Athens.” In P. Murray and P. Wilson, eds., 91–117.

Christesen, P. 2007. “The Transformation of Athletics in Sixth-Century Greece.” In G. Schaus and S. Wenn, eds., 59–68.

Christesen, P. 2012. Sport and Democratization in the Ancient and Modern Worlds. Cambridge.

Connor, W. R. 1971. The New Politicians of Fifth-Century Athens. Indianapolis.

Coulson, W., O. Palagia, T. L. Shear, et al., eds. 1994. The Archaeology of Athens and Attica under the Democracy. Oxford.

Crowther, N. 2004. Athletika: Studies on the Olympic Games and Greek Athletics. Hildesheim.

Fisher, N. 1998. “Gymnasia and the Democratic Values of Leisure.” In P. Cartledge, P. Millett, and S. von Reden, eds., 84–104.

Fisher, N. 2011. “Competitive Delights: The Social Effects of the Expanded Programme of Contests in Post-Kleisthenic Athens.” In N. Fisher and H. van Wees, eds., 175–219.

Fisher, N. and H. van Wees, eds. 2011. Competition in the Ancient World. Swansea.

Flensted-Jensen, P., T. H. Nielsen, and L. Rubinstein, eds. 2000. Polis and Politics: Studies in Ancient Greek History Presented to Mogens Herman Hansen on His Sixtieth Birthday. Copenhagen.

Gardiner, E. N. 1930. Athletics of the Ancient World. Oxford.

Goette, H. R. 2007. “‘Choregic’ or Victory Monuments of the Tribal Panathenaic Contests.” In O. Palagia and A. Choremi-Spetsieri, eds., 117–25.

Golden, M. 1998. Sport and Society in Ancient Greece. Cambridge.

Golden, M. 2008. Greek Sport and Social Status. Austin, TX.

Johnston, A. W. 1987. “IG II.2 2311 and the Number of Panathenaic Amphorae.” Annual of the British School at Athens 82: 125–9.

König, J. 2009. “Games and Festivals in the Greek World.” In G. Boys-Stones, B. Graziosi, and P. Vasunia, eds., 378–90.

Kyle, D. G. 1984. “Solon and Athletics.” Ancient World 9: 91–105.

Kyle, D. G. 1987. Athletics in Ancient Athens. Leiden.

Kyle, D. G. 1992. “The Panathenaic Games: Sacred and Civic Athletics.” In J. Neils, ed., 77–101.

Kyle, D. G. 1997. “The First Hundred Olympiads: A Process of Decline or Democratization?” Nikephoros 10: 53–75.

Kyle, D. G. 2007. Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, MA.

Lee, H. 1999. “Review of Golden, Sport and Society in Ancient Greece.” Journal of Sport History 26: 400–2.

Mann, C. 2001. Athlet und Polis im archaischen und frühklassischen Griechenland. Göttingen.

Marr, J. L. and P. J. Rhodes, eds. 2008. The “Old Oligarch”: The Constitution of the Athenians Attributed to Xenophon, Edited with an Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Oxford.

Miller, S. G. 2000. “Naked Democracy.” In P. Flensted-Jensen, T. H. Nielsen, and L. Rubinstein, eds., 277–96.

Miller, S. G. 2004. Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven.

Murray, P. and P. Wilson, eds. 2004. Music and the Muses: The Culture of “Mousikê” in the Classical Athenian City. Oxford.

Neils, J., ed. 1992a. Goddess and Polis: The Panathenaic Festival in Ancient Athens. Princeton.

Neils, J. 1992b. “The Panathenaia: An Introduction.” In J. Neils, ed., 12–27.

Neils, J. 1992c. “Panathenaic Amphoras: Their Meaning, Makers, and Markets.” In J. Neils, ed., 28–51.

Neils, J. 1994. “The Panathenaia and Kleisthenic Ideology.” In W. Coulson, O. Palagia, T. L. Shear, et al., eds., 151–60.

Neils, J. 1996a. “Pride, Pomp, and Circumstance: The Iconography of Procession.” In J. Neils, ed., 177–97.

Neils, J., ed. 1996b. Worshipping Athena: Panathenaia and Parthenon. Madison.

Neils, J. 2001. The Parthenon Frieze. Cambridge.

Neils, J. 2007. “Replicating Tradition: The First Celebrations of the Greater Panathenaia.” In O. Palagia and A. Choremi-Spetsieri, eds., 41–51.

Neils, J. and P. Schultz. 2012. “Erechtheus and the Apobates Race on the Parthenon Frieze (North XI–XII).” American Journal of Archaeology 116: 195–207.

Neils, J. and S. Tracy. 2003. Tonathenethenathlon: The Games at Athens. Athens.

Osborne, R. 1993. “Competitive Festivals and the Polis: A Context for Dramatic Festivals at Athens.” In A. Sommerstein, S. Halliwell, J. Henderson, et al., eds., 21–37.

Palagia, O. and A. Choremi-Spetsieri, eds. 2007. The Panathenaic Games. Oxford.

Papakonstantinou, Z. 2003. “Alcibiades in Olympia.” Journal of Sport History 30: 173–82.

Phillips, D. 2003. “Athenian Political History: A Panathenaic Perspective.” In D. Phillips and D. Pritchard, eds., 197–232.

Phillips, D. and D. Pritchard, eds. 2003. Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World. Swansea.

Pleket, H. W. 1975. “Games, Prizes, Athletes, and Ideology.” Stadion 1: 49–89.

Pleket, H. W. 2001. “Zur Soziologie des antiken Sports.” Nikephoros 14: 157–212.

Pleket, H. W. 2005. “Athleten in Altertum: Soziale Herkunft und Ideologie.” Nikephoros 18: 151–63.

Pritchard, D. 2003. “Athletics, Education, and Participation in Classical Athens.” In D. Phillips and D. Pritchard, eds., 293–350.

Pritchard, D. 2009. “Sport, War, and Democracy in Classical Athens.” International Journal of the History of Sport 26: 212–45.

Pritchard, D. 2013. Sport, Democracy and War in Classical Athens. Cambridge.

Raubitschek, A. E. 1949. Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis: A Catalogue of the Inscriptions of the Sixth and Fifth Centuries b.c. Cambridge, MA.

Remijsen, S. 2011. “The So-Called ‘Crown Games’: Terminology and Historical Context of the Ancient Agones.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 177: 97–109.

Schaus, G. and S. Wenn, eds. 2007. Onward to the Olympics: Historical Perspectives on the Olympic Games. Waterloo, ON.

Schultz, P. 2007. “The Iconography of the Athenian Apobates Race: Origins, Meanings, Transformations.” In O. Palagia and A. Choremi-Spetsieri, eds., 59–72.

Shear, J. 2003a. “Atarbos’ Base and the Panathenaia.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 123: 164–80.

Shear, J. 2003b. “Prizes from Athens: The List of Panathenaic Prizes and the Sacred Oil.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 142: 87–108.

Sommerstein, A., S. Halliwell, J. Henderson, et al., eds. 1993. Tragedy, Comedy, and the Polis. Bari.

Thorley, J. 2004. Athenian Democracy. London.

Tracy, S. 1991. “The Panathenaic Festival and Games: An Epigraphic Inquiry.” Nikephoros 4: 133–53.

Tracy, S. 2007. “Games at the Lesser Panathenaea?” In O. Palagia and A. Choremi-Spetsieri, eds., 53–8.

Tracy, S. and C. Habicht. 1991. “New and Old Panathenaic Victor Lists.” Hesperia 60: 187–236.

Valavanis, P. 1990. “La proclamation des vainqueurs aux Panathénées: À propos d’amphores panathénaïques de Praisos.” Bulletin de correspondance hellénique 114: 325–59.

Valavanis, P. 2004. Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens. Los Angeles.

Young, D. 1984. The Olympic Myth of Greek Amateur Athletics. Chicago.

Young, D. 2004. A Brief History of the Olympic Games. Oxford.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

Neils and Tracy 2003; Miller 2004: 132–45; and Valavanis 2004: 336–91 offer excellent introductions to the Panathenaic Games. Kyle 1987 innovatively focused on athletics in the city-state of Athens, and several studies have expanded beyond that study. Essential now on the Panathenaia are works written or edited by Neils (1992a–c, 1994, 1996a and b, 2001, 2007); Shear (2003b); and Palagia and Choremi-Spetsieri (2007). On the relevant epigraphical evidence, see Tracy 1991; Tracy and Habicht 1991; and Shear 2003b.

Panathenaic prize amphorae have been much studied and debated; essential now is Bentz 1998, with its extensive, detailed catalog and historical discussions (on events, prizes, changes over time). See also Neils 1992c and essays in Palagia and Choremi-Spetsieri 2007.

On Athenian athletes and social history (class and social mobility), Kyle 1987 remains useful, but see Fisher 1998, 2011; Christesen 2012: 143–51, 164–78; and Pritchard 2003, 2009, and 2013. More generally on Greek athletes and society, see Young 1984, 2004; Golden 1998, 2008; and Pleket 1975, 2001.