Map 11.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

By the end of the sixth century BCE, and for centuries thereafter, the cities and sanctuaries of the northern Peloponnese and central Greece were known for religious festivals that often included athletic competitions.1 Indeed, this was one of the areas of the ancient Greek world where there was the highest concentration of such festivals.

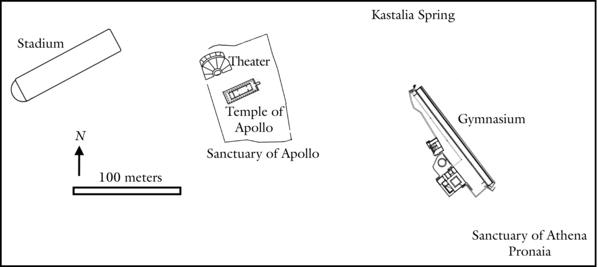

Whereas games at Olympia emerged sometime around the eighth century, major athletic festivals arose in the sixth century at interstate sanctuaries at Delphi in central Greece and at Isthmia and Nemea in the Peloponnese (see Map 11.1). Later known as the periodos or circuit, all four of these “crown” games had contests open to all Greeks, arranged truces, and gave prizes in the form of wreaths, but each one also had its own distinctive features.2 The festivals at Olympia and Nemea, both dedicated to Zeus, were most alike in their athletic programs. The festivals at Delphi and Isthmia, dedicated to Apollo and Poseidon, respectively, had elaborate programs that shared some elements with Olympia, but also featured musical contests that were lacking at Olympia and Nemea. The Peloponnese was also home to a number of other lesser, but still important, athletic festivals, such as those at Epidauros (Miller 2004a: 129–32; Sève 1993).

This essay surveys the locations, sites, history, programs, and operation of the Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games. (On the Olympics, see Chapter 8 in this volume.) It focuses on the Archaic (700–480) and Classical (480–323) periods, with glimpses into the early part of the Hellenistic (323–31) period. It also looks in some detail at the athletic contests held at Mt Lykaion, where recent excavations have produced intriguing new evidence bearing on the history of sport in the Greek world. The concluding section explores the possibility that the athletic contests at Mt Lykaion antedated those at Olympia.

Map 11.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

Our information comes mostly from ancient literary sources, especially Pausanias, and from many years of archaeological work at the various sites. As other essays in this volume demonstrate (see, for example, Chapter 19), although religion and sport took center stage at athletic festivals, the sites, organizers, and even the spectators were on display as well. Social and political interactions and assorted fringe persons and activities (see Chapter 17) were all part of the phenomenon.

Both literary sources and inscriptions show that there was a distinct hierarchy within the periodos, with the Olympics enjoying the most prestige, followed by the Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games (in that order) (Cairns 1991). The Pythian Games, held every fourth year at the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, were thus the second most prestigious set of athletic contests in the Greek world. As at Olympia, the location (on the slope of Mt Parnassos in Phocis, about 600 meters above the Gulf of Corinth) at a hallowed interstate sanctuary of a major god aided the prestige and success of the games.

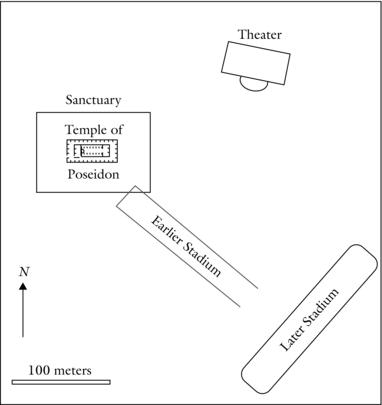

Map 11.2 Plan of the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi and surrounding areas.

According to myth (e.g., Hyginus Fabulae 140), Apollo established a musical contest at Delphi after killing the great serpent Pytho, who guarded the site for his mother Gaia. The site of what became the sanctuary of Apollo (Map 11.2) was occupied in the Late Bronze Age (1600–1100) by an extensive settlement that included cult areas and cemeteries. That settlement was abandoned at the end of the Bronze Age, and there is no sign of sustained activity at the site until c.875 when a new village was established. The first evidence for cult dates to c.825; the finds from the site indicate that it was initially a purely local sanctuary. Religious activity expanded rapidly starting in the early years of the eighth century, and another major upward shift took place at the end of that century, at which point the sanctuary began attracting visitors from increasingly distant places (Morgan 1990: 106–47).

It is likely, though not certain, that the oracle, which became the most famous of its kind in the entire Greek world, started to function sometime in the second half of the eighth century and may have been partly responsible for the increasing popularity of the sanctuary. In later periods, for which much better sources are available, the oracle of Apollo at Delphi was always a priestess who was assisted by male priests. There were typically one or two such priestesses at any given time, and they carried out their duties while sitting in a tripod in the inner sanctum of the Temple of Apollo, perhaps inhaling psychedelic natural gasses from a cleft (Lehoux 2007/8; Morgan 1990: 148–90).

In the early part of the sixth century the Amphictyony of Anthela took over administration of the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. The history of this period is confused, but it would appear that the nearby city-state of Krisa aggressively sought to control movement to and from Delphi by sea and to profit from the flow of visitors to the site. This provoked an attack by a religious association, the Amphictyony of Anthela, which was based in the sanctuary of Demeter at Thermopylai. The resulting conflict, the First Sacred War (c.600–c.586), ended with the defeat of Krisa (Morgan 1990: 113–34; Sánchez 2001: 31–80).

Among the first acts of the Amphictyony after it took charge of the sanctuary of Apollo was to found a quadrennial festival that featured gymnic, equestrian, and musical competitions. 3 This festival built upon a preexisting one that featured a contest in singing a hymn to Apollo to the music of a kithara (a stringed instrument resembling a small harp). The program of the revamped festival was clearly influenced by the Olympic Games, and, like the Olympics, competitors were divided into two age-classes, men and boys. There were, nonetheless, divergences (see Table 11.1); for example, the Pythian Games offered more gymnic events for boys than the Olympics, but did not include boys’ wrestling, which had a long history at Olympia.4 The fundamental difference between the Olympic and Pythian Games, however, was the inclusion in the latter of a number of musical contests. The initial program of musical contests at the Pythian Games consisted of singing to the accompaniment of the kithara, playing the aulos (a kind of flute), and singing to the accompaniment of the aulos. The last of these was not held again after 586, but playing the kithara was added in 558. The program of musical events remained unchanged down through the fourth century, but by the Roman period it had expanded considerably to include dance, drama, acting, painting, and rhetoric (Pausanias 10.7.2–7; Amandry 1990: 306–10; Picard 1989: 72–6; Weir 2004: 21–2).

Table 11.1 List of gymnic and equestrian events at the Olympic and Pythian Games.

| Event | Olympia | Delphi |

| Footraces Men’s stadion Boys’ stadion Men’s diaulos Boys’ diaulos Men’s dolichos Boys’ dolichos Men’s hoplitodromos | yes (776)a yes (632) yes (724) no yes (720) no yes (520) | yes (586) yes (586) yes (586) yes (586) yes (586) yes (586) yes (498) |

| Pentathlon Men’s Boys’ | yes (708) nob | yes (586) yes (586) |

| Combat sports Men’s boxing Boys’ boxing Men’s pankration Boys’ pankration Men’s wrestling Boys’ wrestling | yes (688) yes (616) yes (648) yes (200) yes (708) yes (632) | yes (586) yes (586) yes (586) yes (346) yes (586) no |

| Equestrian events Four-horse chariot race Two-horse chariot race Four-colt chariot race Two-colt chariot race Horse race Colt race | yes (680) yes (408) yes (384) yes (268) yes (648) yes (256) | yes (582) yes (398) yes (378) yes (338) yes (586) yes (314) |

a The numbers in parentheses indicate the year when the event in question was added to the Olympic or Pythian program. The accuracy of the dates at which events were added to the Olympic program prior to the sixth century is questionable. See Christesen 2007: 16–17, 476–8. This chart draws on Christesen 2007: 17 and Miller 2004b: 202 (cf. Weir 2004: 21).

b The boys’ pentathlon was held at the Olympics in 628, then immediately and permanently dropped from the program.

Victors at the first iteration of the Pythian Games in 586 received material prizes, probably tripods, but starting in 582 the only prizes offered were wreaths of laurel (Pausanias 10.7.5).5 Laurel was sacred to Apollo, and the branches from which victors’ wreaths were made came from a tree in the Valley of Tempe (where, according to myth, Apollo had been purified after killing Pytho) (Plutarch Moralia 1136a). Like Olympia, Delphi proclaimed a truce for its games (Amandry 1990: 282–95). Aristotle compiled a list of Pythian victors, as he did for Olympia, and an honorific inscription from Delphi records that Aristotle’s list was to be copied onto stone (Christesen 2007: 179–202).

Archaeological work at Delphi has been conducted under the auspices of the École Française d’Athènes since the nineteenth century CE and during this time much information has come to light about the physical structure of the site. Delphi had a full complement of facilities to support the contests held at the Pythian Games. Originally the athletic events perhaps took place on the plain that lies between Delphi and the sea, and the equestrian events were always held in that area. In the fifth century a stadium was added above the temple; and this structure was subsequently repaired and enhanced on multiple occasions (Aupert 1979). An inscription on its retaining wall prohibits (and sets fines for) bringing wine into the stadium (Corpus des inscriptions de Delphes 1.3; Miller 2004b: no. 100). Other athletic facilities at Delphi include a substantial gymnasion complex, which was built c.330 and which featured a palaistra, covered and outdoor tracks, baths, and a small pool.6 The theater, which was located just above the temple and which was the site of the musical contests held as part of the Pythian Games, dates to the second century. The siting of the musical contests before the third century, when they were held in the stadium, is unknown (Bommelaer 1991: 207–12).

The sanctuary at Delphi was also home to a famous temple, treasuries, and numerous votive dedications. Pausanias, who visited the site in the second century CE, recorded a local tradition that there were three successive early temples of Apollo on the site, made from laurel, bees’ wax and feathers, and bronze (10.5.9–12). No trace of such structures has survived, and the earliest extant remains of a temple at Delphi date to the second half of the seventh century. The Apollo temple currently visible on the site was erected in the fourth century (Bommelaer 1991: 176–84; Morgan 1990: 129–35; Scott 2010: 25, 56–9, 65–6, 114, 118, 137–8, 230). Some of the most famous buildings at Delphi are treasuries, small structures erected by individual communities to house expensive votive offerings. Approximately thirty different treasuries existed at Delphi at various points in time and boasted some of the most elaborate architecture and sculpture at the site (Partida 2000; Scott 2010: 41–145). Delphi also housed magnificent works of art, most of which are no longer extant. We are, however, fortunate to have the famous bronze statue known as the Charioteer of Delphi. Only the charioteer and minor pieces remain from an original dedication made c.474 by Polyzalos, tyrant of Gela in Sicily, and consisting of a statue group of a four-horse chariot with a victor and driver. (For further discussion and an illustration, see Chapter 12.)

The sanctuary of Isthmia was located about 13 kilometers east of Corinth, on the eastern side of the Isthmus of Corinth and directly on major north–south and east–west land and sea routes. Both the sanctuary and the games held there were supervised by the city-state of Corinth.

There were two different mythical accounts of the origins of the Isthmian Games. In one, King Sisyphos of Corinth founded funeral games for his nephew Melikertes, who had drowned nearby (Pausanias 1.44.7–8). The other myth (Plutarch Theseus 25.4–5) says Theseus of Athens founded games for Poseidon at the Isthmus because Herakles began games for Zeus at Olympia. Different traditions say Theseus started the games to honor Skiron or Sinis, whom he killed in his labors.

Archaeological finds (e.g., ritual vessels, terracotta dedications) indicate cult activity at the site from the mid-eleventh century on, and early metal dedications (Jackson 1992) show increasing elite participation from c.700 on. As at Olympia, a local sanctuary became the focus of expanding interest. By tradition, in 580, an earlier festival at Isthmia was reorganized to be held biennially, two years before, the same year as, and two years after the Olympic Games (Gebhard 1989: 82–4; 1993a; 2002; Miller 2004a: 101–4; Morgan 2002). Corinth was sacked by the Romans in 146, at which point the Isthmian Games were transferred to Sicyon, which lay just to the west of Corinth. When Corinth was resettled in 44, the Isthmian Games were returned to Corinthian control (Gebhard 1993b; Gebhard, Hemans, and Hayes 1998; Kajava 2002).

The program of events at the Isthmian Games was closer to that at the Pythian than the Olympic Games in that it included not only gymnic and equestrian competitions, but also musical contests. The textual sources for the history of the Isthmian (and Nemean) Games are significantly less abundant than those for the Olympic and Pythian Games, and it is, as a result, not possible to recount in detail the evolution of the program of events at Isthmia (Christesen 2007: 108–12). We do know that competitors at Isthmia were divided into three age-classes (boys, youths, and men) and that there was a footrace called the hippios, in which competitors ran a distance of four stadia (roughly 800 meters), that was not held at the Olympic or Pythian Games (Bacchylides 10.24–6; Pausanias 6.16.4).7 We also know that there were various contests in music, recitation, writing, painting, and, apparently, a boat race. Unfortunately, it is for the most part unclear when a particular contest was first held. The original prize of a wreath of pine was later changed to a wreath of dry celery, perhaps out of rivalry with Nemea (Plutarch Moralia 676f; Broneer 1962).

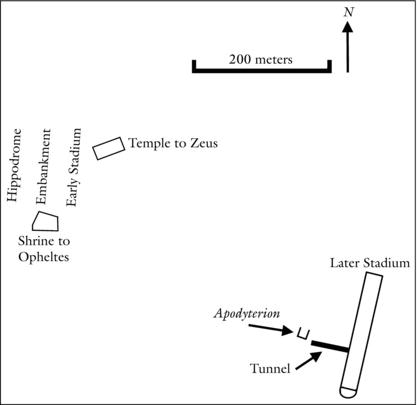

Excavations under the auspices of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens have revealed the remains of two stadia, of different dates, at Isthmia (see Map 11.3). The earlier stadium, situated close to the Temple of Poseidon, was initially constructed in the early part of the sixth century, at the time of the establishment of the Isthmian Games. In order to create a sufficiently large level space, tons of fill were brought in, and the original ground level was in some places raised more than five meters. This stadium was reconstructed in the later fifth century, at which time a new starting line, complete with postholes and a starter’s pit, was installed. This pit seems to have been part of a mechanism (hysplex) consisting of 16 wooden gates that opened when the starter released ropes leading to each gate. Soon this system was replaced with a traditional starting line with single toe grooves.8 The later stadium, which dates to the end of the fourth century, lies some 250 meters to the southeast of the Temple of Poseidon; it awaits full excavation (Gebhard 1992; Romano 1993: 24–33, 81–4; Miller 2004a: 38–40).

Map 11.3 Plan of the sanctuary of Poseidon at Isthmia and surrounding areas.

Other facilities at Isthmia included a theater and a hippodrome. The earliest theater at the site dates to the fifth century and was located 50 meters northeast of the Temple of Poseidon. This structure was repeatedly remodeled in the centuries that followed. The location of the hippodrome is not known for certain, but it has been suggested that it was situated 2 kilometers to the west of the sanctuary (Gebhard 1973, 1989: 86–8).

Isthmia was also notable for an array of religious architecture, including a well-known Temple of Poseidon. The first such temple at the site was built in the second half of the seventh century and featured recent architectural innovations, including clay roof tiles and exterior walls adorned with painted decoration. This structure burnt to the ground c.470 and was rapidly replaced, though that building too was damaged by fire, in 390. The rebuilt temple stood until the end of the fourth century CE (Broneer 1971; Gebhard 1989: 84–5; Morgan 2003: 143–8).

The festival at Isthmia attracted crowds from all over the Greek world and offered opportunities for political announcements and enterprising sophists and merchants. An oration of 97 CE by Dio Chrysostom (Orations 8.9–12; Miller 2004a: no. 145), ostensibly recounting a visit by Diogenes the Cynic to the Isthmian Games in the mid-fourth century, reveals various extraneous activities (see Chapter 17). Unfortunately, the festival also experienced political intrigue and violence. Owing to a mysterious “Curse of Moline” (Pausanias 5.2.1–2) Eleians boycotted the Isthmian Games throughout antiquity (Pausanias 6.3.9, 6.16.2). At the games of 412 Athenians were able to learn of a Peloponnesian naval effort to support an anti-Athenian revolution at Chios (Thucydides 8.9.1–2). In 390 Argos and Sparta battled for control of the sanctuary and rival games were staged by Argos and Corinth (Xenophon Hellenika 4.5.1–2,4). Isthmia nevertheless suffered less disruption than Nemea.

Nemea was located 30 kilometers southwest of Corinth in a remote, rural area of the Peloponnese. The Nemean Games were the least prestigious of the four sets of contests that made up the periodos and were relatively short lived, but our knowledge of the history of the site and the operation of the athletic festival is abundant thanks to excavations conducted under the auspices of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Two foundation myths concern the establishment of this festival. The first is the story of Herakles who killed the Nemean lion here as the first of his 12 labors and ostensibly founded the Nemean Games while at the site. The other myth involves the death of Opheltes, infant son of King Lycurgus of Nemea, who was killed by a snake. After his death, the story goes, a hero cult and funeral games were established with crowns of wild celery (Hyginus Fabulae 74; Apollodorus Library 3.6.4).

In 573 the community of Kleonai built a temple for Zeus at what seems to have been a preexisting sanctuary at Nemea and established a festival in his honor. Kleonai had a close but complicated relation with the much larger and more powerful city-state of Argos, about 25 kilometers to the southeast, and Argos clearly played an important role in the administration of the Nemean Games throughout their history. The sanctuary suffered a major, violent destruction c.415 and lay in ruins for several decades thereafter; in the aftermath of this incident the Nemean Games were likely moved to Argos. In the closing decades of the fourth century they were returned to Nemea, and an impressive building program restored and embellished the sanctuary. However, the Nemean Games were being held once again in Argos by c.270, and the sanctuary of Zeus at Nemea suffered a gradual decline (Miller 1989, 1992, 2004a: 105–11). When Pausanias visited the site in the second century CE, it was largely abandoned (2.15.2–3).

The Nemean Games included both gymnic and equestrian contests; musical contests were not part of the initial program but were added after the end of the Classical period. Like Isthmia, competitors were divided into three age groups, and the gymnic competitions included the hippios. Inscriptions show that a truce was announced and envoys (theoroi) were sent throughout Greece in groups of six, visiting various cities and being received by local representatives (Miller 1988). Victors received a crown of wild celery (Miller 2004a: 107).

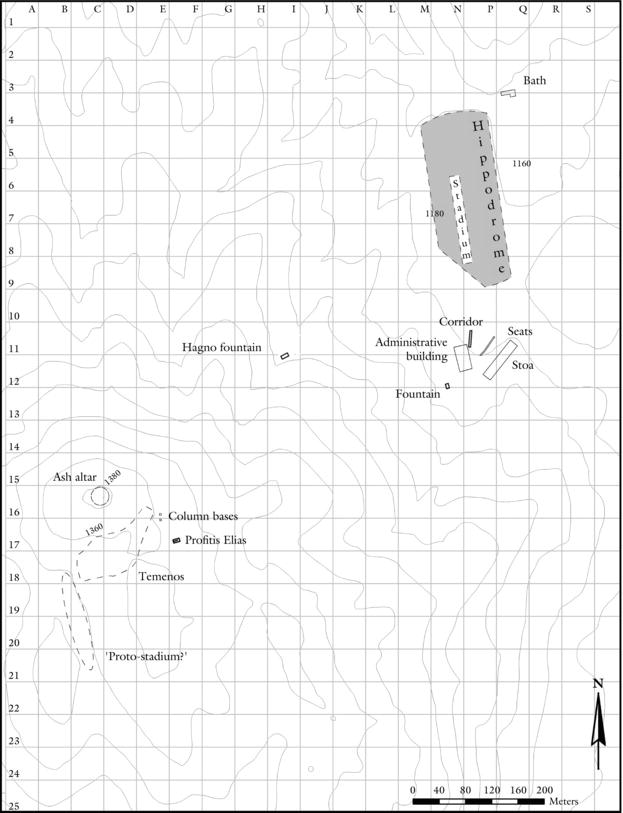

There were two major building phases at Nemea, one linked to the foundation of the Nemean Games in 573 and another to the return of the games in the 330s. The structures associated with the first phase included a temple to Zeus and a shrine to Opheltes (see Map 11.4). The Opheltes shrine, perhaps inspired by the Pelopeion at Olympia, featured an embankment that accommodated spectators at a stadium and hippodrome that were located on either side of it (Miller 2002; 2004a: 37–8, 110–11). The late fourth-century building program included a new stadium located 450 meters southeast of the temple. Its original and traditional starting line with a stone sill and grooves was later recut (after the 330 s but before the 270s) to accept a new starting mechanism (hysplex) using the tension from twisted rope to drop rope barriers from all the lanes at the same time (see Chapter 18). A well-preserved 36 meter-long vaulted entrance tunnel with extant graffiti on its walls connected the stadium to a changing room (apodyterion). Many roof tiles from the structure were found, complete with the name Sosikles, the Argive architect in charge of the construction (Miller 2001: 164–72).

Map 11.4 Plan of the sanctuary of Zeus at Nemea and surrounding areas.

As noted at the start of the chapter, a substantial number of communities and sanctuaries in central Greece and the northern Peloponnese hosted athletic festivals that, although not as prestigious as the games of the periodos, nonetheless were of considerable significance. One of the most intriguing festivals was held at the sanctuary of Zeus on Mt Lykaion, which was in the Archaic and Classical periods (and perhaps at other times) the most prominent sanctuary in Arcadia (Jost 1985: 183–5).

The relevant literary and epigraphic evidence makes it clear that by the early part of the fifth century Mt Lykaion was the site of an important athletic festival, the Lykaia. Pindar refers in his epinikia (odes celebrating athletic victories) to the Lykaia on several occasions (Olympian 7.84, 9.97, 13.108; Nemean 10.45–8). He tells us that the prize at the Lykaion Games was bronze, possibly, though not certainly, in the form of tripods (Ringwood 1927: 97). (Tripods were a common form of athletic prize from an early period in the Greek world; see Chapter 3.) The question of whether the festival was held every second or fourth year remains under study. It appears that the Lykaion Games were moved from Mt Lykaion to the city of Megalopolis in the third century.

Invaluable insight into the program of events is provided by two inscriptions recovered in excavations at the site undertaken by Konstantinos Kourouniotis in the early part of the twentieth century (Inscriptiones Graecae V 2 549–50).9 These inscriptions contain lists of victors at five or six different iterations of the Lykaion Games from the end of the fourth century. At that point in time the gymnic component of the Lykaion Games consisted of contests for boys in the stadion, wrestling, and boxing and for men in stadion, diaulos, dolichos, hoplitodromos, pentathlon, boxing, wrestling, and pankration. The equestrian component of the festival was comprised of a two-horse chariot race, a four-colt chariot race, and a horse race.10

The majority of the victors in the inscriptions come from either Arcadia or Argos, suggesting that most participants did not travel great distances, but a sprinkling of victors from other places, including Miletos and Syracuse, shows that the Lykaia’s appeal was more than local. At least some elite athletes took part since Diagoras of Rhodes, one of the most successful athletes of his generation, won the boxing contest at the Lykaion Games at some point in the first half of the fifth century (Pindar Olympian 7.84). Furthermore, the inscriptions from the site show that the pentathlon at one iteration of the festival was won by an Arcadian named Alexibios, whom Moretti has plausibly identified with the athlete of the same name who won the pentathlon at Olympia in 312 (Moretti 1957: no. 483).

Another notable victor was Lagos, son of Ptolemy, who appears in the inscriptions as a winner of the two-horse chariot race (Inscriptiones Graecae V 2 550, ll. 8–9). This was almost certainly one of the sons of King Ptolemy I of Egypt (Criscuolo 2003: 312 n. 4), which indicates that the Lykaia had a sufficiently high profile to attract the attention of the Ptolemies, who were avid competitors in equestrian events in athletic festivals in the Greek homeland. (For further discussion of the Ptolemies’ equestrian ambitions, see Chapter 23.)

In the past decade ongoing work undertaken as part of the Mt Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project directed by the 39th Ephoreia of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities in Tripolis in collaboration with and under the auspices of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens has greatly extended our knowledge of the site (see Map 11.5). The physical remains at Mt Lykaion are clustered in two distinct areas: the southern peak of Mt Lykaion (at 1,382 meters above sea level) and in a meadow about 200 meters below the peak (Romano 2005; Romano and Voyatzis 2010). At the former site there is an ash altar and temenos (sacred precinct) dedicated to Zeus. In the meadow there exists a hippodrome, a stadium, a stoa, an administrative building, a bath facility, two fountain houses, and an area of stone seats. Pausanias also mentions a sanctuary of Pan in this area (8.36.5), though it has not to date been located. Many of the structures in the meadow were likely built in the second quarter of the fourth century. The archaeological evidence associated with the hippodrome, and the aforementioned victor inscriptions, suggest that the hippodrome was in use in the fourth century; it is not yet clear when it was constructed.

Map 11.5 Plan of the sanctuary of Zeus at Mt Lykaion and surrounding areas.

The hippodrome is of great interest because it is the only example in the entire Greek world that can be visualized and measured. It is situated on a flat piece of land that is partially cut down from the bedrock and partially artificially filled. The overall dimensions of the hippodrome are 260 meters long and 102 meters wide. Its shape is irregular, with an oblique side on the southwest end where it intersected a low terrace wall. To the north, west, and east sides the available space for the hippodrome was limited by several low hills. There is no retaining wall to the north, but there are the remains of one to the east.

Parts of two tapering, stone columns that are likely to have been the turning posts for the facility have been recovered from the modern surface of the hippodrome. Each is characterized by several unfluted column drums that once stood together on a stone base. The total restored height of each of the turning posts was 2.94 meters, although there may have been small capping stones on top of the column drums that have not been found. We do not have their original locations, but Kourouniotis, the original excavator, found them approximately 60 meters apart.

Recent excavations have included work in the hippodrome, and some of our results have included finding the surface of the hippodrome floor, which consisted of hard packed clay, in several places. Geophysical remote sensing and excavation has produced no evidence for an interior barrier wall, as commonly found in Roman circuses. In addition, geophysical remote sensing has not found evidence of starting gates at either end of the facility.

The hippodrome is also noteworthy because it has within its limits the dromos (track) of a stadium. It appears that the hippodrome and stadium were constructed as two parts of a whole. The combination of hippodrome and stadium in one facility is not known from any other site in mainland Greece, which makes the details of the facility at Mt Lykaion of considerable importance.11

The archaeological evidence for the stadium, which is mentioned by Pausanias (8.38.5) in the context of describing the sanctuary of Pan and the hippodrome, consists of seven stone starting line blocks that have been discovered on the modern surface of the meadow. Several of these blocks were found immediately adjacent to one another. They have two parallel grooves, and some of them include postholes. The location of most of the starting line blocks, in a line toward the middle of the hippodrome, suggests that they have been found in situ or close to their original positions. Although the other end of the dromos has yet to be discovered, there is at the southern end of the hippodrome a low terrace wall that would prevent the dromos exceeding a distance of approximately 138 meters. Other than a few stone blocks that Kourouniotis found at the southern end of the hippodrome, no other formal seating facilities for the hippodrome or the stadium have been discovered.

The Olympics have long been believed to be the earliest Greek athletic festival, and the claim made by the Roman author Pliny the Elder that the first gymnic contests in Greece were held not at Olympia but at Mt Lykaion has typically been dismissed as inaccurate (Natural History 7.205; cf. Pausanias 8.2.1). New excavations at Mt Lykaion, however, have produced evidence that may suggest that Pliny’s claim should be taken seriously.

The area in and around Mt Lykaion is linked in Greek mythology to the very earliest periods of Greek history. Pausanias (8.1.4–2.1) tells us that Pelasgos was the first inhabitant of Arcadia and was chosen as king. He introduced huts for the Arcadians to live in, sheep skins to wear, and nuts, specifically acorns, to eat. According to this myth, Pelasgos’ son Lykaon founded the city of Lykosoura, which Pausanias describes as the oldest city in the world, and the Lykaion Games.

Until recently there was no archaeological material that supported claims found in myth that there was activity at the sanctuary of Zeus on Mt Lykaion from an early period. Kourouniotis working at the site in the early twentieth century found evidence at the ash altar of Zeus at Mt Lykaion going back no farther than the seventh century, in the form of two miniature bronze tripods (Kourouniotis 1904: 166, figs. 3–4).

The Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project, however, has produced much evidence that shows that cult activity at the site began at a very early date and went on continuously from at least the Late Bronze Age through to the Classical period. New excavations at the ash altar on the peak of Mt Lykaion have uncovered pottery from the Final Neolithic period (c.4500–c.3000) and all three phases of the Bronze Age (the Early, Middle, and Late Helladic periods, cumulatively covering c.3000–c.1100). Moreover, a shrine dating to the Mycenaean period (i.e., the Late Helladic period, 1600–1100) was found on the bedrock of the mountaintop. The finds from this shrine include hundreds of Mycenaean drinking vessels (kylikes), other open mouth vessels, and terracotta animal and human figurines. There is also a considerable amount of material from all of the post-Bronze Age chronological periods, down through the fourth century (Romano and Voyatzis 2010: 13–14). It is, as a result, now possible to demonstrate that the ash altar at Mt Lykaion was in unbroken use for well over a millennium, and perhaps longer.

These important finds suggest that it is time to reevaluate Pliny’s claim that the earliest gymnic contests in the Greek world were held at Mt Lykaion. We know that sport was a notable part of Mycenaean civilization (see Chapter 2), that there was a significant amount of activity at Mt Lykaion in the Mycenaean period and thereafter, and that, by the fifth century at the latest, athletic contests were being held on Mt Lykaion. It is, therefore, entirely possible that such contests were held at Mt Lykaion during Mycenaean times, and thus, as Pliny claims, long before athletic contests began at Olympia. There is as yet no direct evidence for athletic activity at Mt Lykaion prior to the fifth century, but miniature bronze tripods, which probably date to the tenth century and which are similar to those excavated at Olympia, have been found in the ash altar at Mt Lykaion. Were these in some way related to athletic competition? We do not yet know.

The sanctuary of Zeus at Mt Lykaion is only 37 kilometers as the eagle flies from the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia. These two sanctuaries have much in common. Both were famous for their ash altars and their athletic contests. The cult of Zeus was introduced at Olympia in the second half of the eleventh century, whereas the new archaeological evidence discussed above suggests that Zeus was worshipped at the ash altar at Mt Lykaion from at least the sixteenth century. The ash altar at Mt Lykaion is literally a mountaintop, sometimes called the Olympos of Arcadia (Pausanias 8.38.2), whereas the ash altar at Olympia is in the form of a conical peak, artificially created, in a river valley and near the sea. The archaeological evidence suggests that Olympia may have been influenced by Mt Lykaion and that the cult of Zeus perhaps first manifested itself there and was then transported to Olympia, complete with an ash altar and athletic contests.

NOTES

1 All dates are BCE unless otherwise indicated.

2 On the designation of these festivals as “crown” games, see Chapter 23. The periodos games were timed so that they never overlapped. See Miller 2004a: 111–12.

3 For a definition of the term “gymnic” and details of the various events, see Chapter 1.

4 A footrace for girls was added in the Roman period; see Chapter 36.

5 There has been much scholarly debate about the date of the first Pythiad. See Miller 1978 and Mosshammer 1982.

6 For a definition of the term palaistra and for more on the gymnasion at Delphi, see Chapter 19.

7 On age-classes at Greek athletic contests, see Chapter 14.

8 For further discussion of starting mechanisms in Greek stadia, see Chapter 18.

9 The content of these inscriptions is discussed in Ringwood 1927: 95–7 and described and discussed in Datsouli-Stavridi 1999: 33–6.

10 Four of the victor lists are complete. What seems to be the first in the sequence indicates that, at that particular iteration of the festival, a four-horse chariot race was also held. This race appears only once in the other three complete lists. In addition, the fifth list in the sequence catalogs victors only in the two-horse chariot race, the four-colt chariot race, and the men’s dolichos. The entirety of this list is preserved, and it is unclear whether a complete list of victors for that iteration of the festival was never inscribed, or whether the program of events was, for reasons unknown, abridged. The following list indicates that the full program of events was held at the next iteration of the festival.

11 In the Roman period, some smaller circuses in the eastern Mediterranean doubled as stadia. See the discussion in Dodge’s essay, CHAPTER 38, on sites other than amphitheaters.

REFERENCES

Amandry, P. 1990. “La fête des Pythia.” Pratika tes Akademias Athenon 65: 279–317.

Aupert, P. 1979. Fouilles de Delphes II.4: Le Stade. Paris.

Birge, D., L. Kraynak, and S. Miller. 1992. Excavations at Nemea I: Topographical and Architectural Studies: The Sacred Square, the Xenon, and the Bath. Berkeley.

Bommelaer, J.-F. 1991. Guide de Delphes: Le site. Paris.

Broneer, O. 1962. “The Isthmian Victory Crown.” American Journal of Archaeology 66: 259–63.

Broneer, O. 1971. The Temple of Poseidon. Princeton.

Broneer, O. 1973. Topography and Architecture. Princeton.

Cairns, F. 1991. “Some Reflections on the Ranking of the Major Games in Fifth Century B.C. Epinician Poetry.” In A. Rizakes, ed., 95–8.

Christesen, P. 2007. Olympic Victor Lists and Ancient Greek History. Cambridge.

Coulson, W. and H. Kyrieleis, eds. 1992. Proceedings of an International Symposium on the Olympic Games, 5–7 September 1988. Athens.

Criscuolo, L. 2003. “Agoni e politica alla corte di Alessandria: Riflessioni su alcuni epigrammi di Posidippo.” Chiron 33: 311–32.

Datsouli-Stavridi, A. 1999. Archaiologike Sulloge Megalopoles: Katalogos. Athens.

Fontenrose, J. 1988. “The Cult of Apollo and the Games at Delphi.” In W. Raschke, ed., 121–40.

Gebhard, E. 1973. The Theater at Isthmia. Chicago.

Gebhard, E. 1989. “The Sanctuary of Poseidon on the Isthmus of Corinth and the Isthmian Games.” In O. Tzachou-Alexandri, ed., 82–8.

Gebhard, E. 1992. “The Early Stadium at Isthmia and the Founding of the Olympic Games.” In W. Coulson and H. Kyrieleis, eds., 73–80.

Gebhard, E. 1993a. “The Evolution of a Pan-Hellenic Sanctuary: From Archaeology to History at Isthmia.” In N. Marinatos and R. Hägg, eds., 154–77.

Gebhard, E. 1993b. “The Isthmian Games and the Sanctuary of Poseidon in the Early Empire.” In T. Gregory, ed., 78–94.

Gebhard, E. 2002. “The Beginnings of Panhellenic Games at the Isthmus.” In H. Kyrieleis, ed., 221–37.

Gebhard, E., F. Hemans, and J. Hayes. 1998. “University of Chicago Excavations at Isthmia, 1989. 3.” Hesperia 67: 405–56.

Gregory, T., ed. 1993. The Corinthia in the Roman Period. Ann Arbor.

Gutsfeld, A. and S. Lehmann. 2005. “Vom Wettkampfplatz zum Kloster: Das Zeusheiligtum von Nemea (Peleponnes) und seine Geschichte in der Spätantike.” Antike Welt 36: 33–41.

Jackson, A. 1992. “Arms and Armour at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Poseidon at Isthmia.” In W. Coulson and H. Kyrieleis, eds., 141–4.

Jost, M. 1985. Sanctuaires et cultes d’Arcadie. Paris.

Kajava, M. 2002. “When Did the Isthmian Games Return to the Isthmus? (Rereading ‘Corinth’ 8.3.153).” Classical Philology 97: 168–78.

Kourouniotis, K. 1904. “Anaskaphai Lykaiou.” Archaiologike Ephemeris: col. 153–214.

Kourouniotis, K. 1909. “Anaskaphai Lykaiou.” Praktika: 185–200.

Kyle, D. 2007. Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, MA.

Kyrieleis, H., ed. 2002. Olympia 1875–2000: 125 Jahre deutsche Ausgrabungen. Mainz.

Lambert, S. 2002. “Parerga II: The Date of the Nemean Games.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 139: 72–4.

Lehoux, D. 2007/8. “Drugs and the Delphic Oracle.” Classical World 101: 41–56.

Marinatos, N. and R. Hägg, eds. 1993. Greek Sanctuaries: New Approaches. London.

Miller, S. 1978. “The Date of the First Pythiad.” California Studies in Classical Antiquity 11: 127–58.

Miller, S. 1988. “The Theorodokoi of the Nemean Games.” Hesperia 57: 147–63.

Miller, S. 1989. “Nemea and the Nemean Games.” In O. Tzachou-Alexandri, ed., 89–96.

Miller, S. 1992. “The Stadium at Nemea and the Nemean Games.” In W. Coulson and H. Kyrieleis, eds., 81–6.

Miller, S. 2001. Excavations at Nemea II: The Early Hellenistic Stadium. Berkeley.

Miller, S. 2002. “The Shrine of Opheltes and the Earliest Stadium at Nemea.” In H. Kyrieleis, ed., 239–50.

Miller, S. 2004a. Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven.

Miller, S. 2004b. Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources. 3rd ed. Berkeley.

Miller, S. and J. Bravo. 2004. Nemea: A Guide to the Site and Museum. Athens.

Moretti, L. 1957. Olympionikai: I vincitori negli antichi agoni olimpici. Rome.

Morgan, C. 1990. Athletes and Oracles. Cambridge.

Morgan, C. 2002. “The Origins of the Isthmian Festival.” In H. Kyrieleis, ed., 251–71.

Morgan, C. 2003. Early Greek States beyond the Polis. London.

Mosshammer, A. 1982. “The Date of the First Pythiad Again.” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 23: 15–30.

Østby, E., ed. 2005. Ancient Arcadia. Athens.

Partida, E. 2000. The Treasuries at Delphi: An Architectural Study. Jonsered, Sweden.

Picard, O. 1989. “Delphi and the Pythian Games.” In O. Tzachou-Alexandri, ed., 69–81.

Raschke, W., ed. 1988. The Archaeology of the Olympics: The Olympic and Other Festivals in Antiquity. Madison.

Ringwood, I. C. 1927. “Agonistic Features of Local Greek Festivals Chiefly from Inscriptional Evidence.” PhD diss., Columbia University.

Rizakes, A., ed. 1991. Archaia Achaia und Elis. Athens.

Romano, D. 1993. Athletics and Mathematics in Archaic Corinth: The Origins of the Greek Stadion. Philadelphia.

Romano, D. 2005. “A New Topographical and Architectural Survey of the Sanctuary of Zeus at Mount Lykaion.” In E. Østby, ed., 381–96.

Romano, D. and M. Voyatzis. 2010. “Excavating at the Birthplace of Zeus.” Expedition 52: 9–21.

Sánchez, P. 2001. L’Amphictionie des Pyles et de Delphes: Recherches sur son rôle historique, des origines au IIe siècle de notre ère. Stuttgart.

Scott, M. 2010. Delphi and Olympia: The Spatial Politics of Panhellenism in the Archaic and Classical Periods. Cambridge.

Sève, M. 1993. “Les Concours d’Épidaure.” Revue des études grecques 106: 303–28.

Tzachou-Alexandri, O., ed. 1989. Mind and Body: Athletic Contests in Ancient Greece. Athens.

Valavanis, P. 2004. Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens. Los Angeles.

Weir, R. G. A. 2004. Roman Delphi and Its Pythian Games. Oxford.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

For illustrated general overviews of Greek sport, and discussion of most of the games treated here, see Tzachou-Alexandri 1989: 69–96; Miller 2004a: 95–112; or Kyle 2007: 136–49. Valavanis 2004: 162–335 offers a clear and lavishly illustrated treatment of the same subject, though without systematic citation of the relevant scholarly literature. On the program of events at the Panhellenic athletic festivals in the fifth century BCE, see Neumann-Hartmann 2007.

On Delphi and the Pythian Games, see Amandry 1990; Fontenrose 1988; Lehoux, 2007/8; Miller 2004a: 95–112; Morgan 1990: 106–90; Picard 1989; Scott 2010: 41–145; and Valavanis, 2004: 162–267. On the history of the site and games in later periods, see Weir 2004.

On Isthmia and the Isthmian Games, much of the fundamental work has been done by Oscar Broneer and Elizabeth Gebhard. Of particular note are Broneer 1973 and Gebhard 1973, 1989, 1992, 1993a, b, 2002. See also Jackson 1992; Kajava 2002; Miller 2004a: 101–5; Morgan 2002; and Valavanis 2004: 268–303.

On Nemea and the Nemean Games, much of the fundamental work has been done by Stephen Miller. Of particular note are Miller 1988, 1989, 1992, 2001, 2002, 2004a: 105–12. See also Birge, Kraynak, and Miller 1992; Gutsfeld and Lehmann 2005; Lambert 2002; Miller and Bravo 2004; and Valavanis 2004: 304–35.

On Mt Lykaion and the Lykaion Games, see Kourouniotis 1904 and 1909; Romano 2005; and Romano and Voyatzis 2010. Information about the ongoing excavations at the site can be found at lykaionexcavation.org.

Neumann-Hartmann, A. 2007. “Das Wettkampfprogramm der panhellenischen Spiele im 5. Jh. v. Chr.” Nikephoros 20: 113–51.