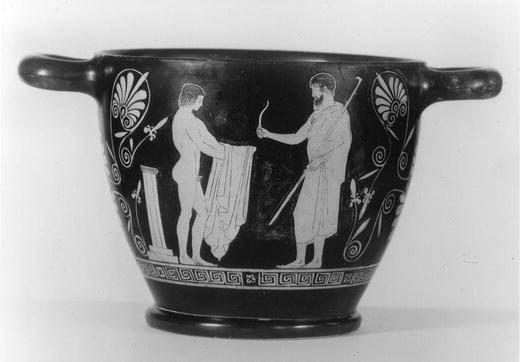

Figure 15.1 Athenian skyphos showing a courtship scene, attributed to the Lewis Painter, c.460BCE. Source: Copyright © Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California. Catalog No. 8-4581.

In today’s world, with the appearance of famous athletes such as David Beckham and Rafael Nadal in provocative underwear advertisements, and a handful of (admittedly almost all ex-) professional athletes speaking openly about their sexual orientation, one could say that the connection between sport and eros is finally beginning to come out of the closet – after years of reticence, on the part of both the public and sports scholars (Guttmann 1996: 1–11). Such reticence was largely absent in the ancient Greek world. Courtship of athletes in the gymnasion was a respectable activity for an elite Greek man, and praise of athletes’ beauty – or of their general excellence – was apparently a common topic for conversation, both between athletes and their admirers and among admirers. Moreover, Greek art (especially sculpture and vase painting) and literature (from lyric poetry to comedy to philosophy) openly portray and celebrate the attractiveness of athletes and the courtship of athletes in the gym. There were, furthermore, competitions for athletic beauty at major athletic festivals, such as the euandria (competition for “good-manliness”) at the Panathenaic Games in Athens (Crowther 2004: 333–9). And Eros (the god/personification of eros, “desire”) received cult worship, along with Hermes and Herakles, as a tutelary deity of several famous gymnasia, including the Academy in Athens (Athenaeus 561d; Pausanias 1.30.1; Plutarch Solon 1.4).1

Aside from its higher profile, there are at least two further key differences between the way the nexus between sport and eroticism manifests itself in ancient Greek and modern cultures. First, although there are a few references to the attractiveness of female athletes in Sparta (see in particular Plutarch Lycurgus 15.1),2 or to women spectators’ potential attractions to victorious athletes (see Pindar Pythian 9.96–100 and 10.55–9), eroticism linked to sport in Greek culture was almost exclusively homoerotic – unsurprisingly, given the degree to which participation in and even spectatorship of sport was restricted to males. More specifically, the eroticism in question was pederastic; that is, the athletes whose beauty was praised and who were courted were young males in puberty or adolescence, and the people praising or courting them were adult men.

Paiderastia, or Greek pederasty – the practice of erotic relations between adult and adolescent males – was typical of ancient Greek culture from the beginning of historic times to the end of pagan antiquity. It was generally viewed in a highly idealizing and idealistic fashion, although doubts about its ethical value seem to have developed in Athens in the Classical period (480–323 BCE) and to have persisted in later periods. Pederastic relationships combined, or were at least supposed to combine, erotic with pedagogical elements. They comprised in effect a system of one-on-one tutoring for elite Greek youths (called in this context the eromenos, “beloved one;” plural eromenoi) in the virtues their society valued, such as moderation and courage, which their lover (called an erastes, “lover;” plural erastai) was supposed to embody. Thus, given the role that sport played in Greek education (see Chapter 14 in this volume), it was natural for paiderastia and sport to be strongly linked and for Greeks not only to acknowledge but also to celebrate the connection between these two aspects of what in their view constituted the ideal male life.

A second key difference that must be borne in mind is that Greek athletes worked out and competed in the nude (see Chapter 13). Greek athletic nudity (and the associated nudity of males in Greek art) may have had nonerotic resonances as well as erotic ones, but clearly both paiderastia and athletic nudity were parts of a culture that placed a high value on young, athletically developed male bodies. It is also clear that the nudity of Greek athletes served to intensify the erotic aspect of Greek athletics.

We will continue our exploration of the connection between eros and sport by looking at some of the more important relevant textual and visual sources. The section on textual sources will cover four areas: myth, poetry, Athenian texts from the Classical period, and later texts.3 The section on visual sources will cover three: sculpture, kalos inscriptions, and vase painting. It is important to bear in mind that the themes of paiderastia and sport are so constantly linked in Greek discourse that it would be impossible within the bounds of this relatively brief essay to survey the relevant material completely.

We will then go on to consider three of the main questions about the eros–sport nexus in current scholarship: (1) whether or in what way the origins of paiderastia and Greek sport, or more specifically nude athletics, were linked; (2) whether erastai may at times have taken a more direct role in Greek boys’ athletic education than is traditionally believed, either by providing them with funding or by serving as their trainer; and (3) why Greek athletes practiced what is generally, if incorrectly, known as infibulation, the binding of their foreskins or penises with a cord before exercising.

Several myths connect athletics and paiderastia. For example, Pelops, one of the mythical founders of the Olympic Games, is described as the eromenos of Poseidon. Indeed, it is through Poseidon’s intervention that he wins a chariot race that brings him a bride and that, according to some Greek authors, led to the foundation of the Olympics.4 Pelops’s son, Chrysippos, is abducted by Oedipus’s father Laios, who falls in love with him while teaching him how to drive a chariot (Apollodorus Library 3.5.5). Paiderastia also features prominently in the myth of Hyakinthos, a Spartan youth who is Apollo’s (and also the wind-god Zephyros’s) eromenos and who is killed by an unlucky throw of the god’s discus.5 These stories show that just as Greek authors tended to see relations between adult men and adolescent males as erotic, so they tended to imagine these erotic relations as taking place in the context of athletics.

A connection between paiderastia and sport is also apparent in Greek poetry starting in the sixth century BCE6 and continuing for centuries thereafter. Some poets praise the beauty of athletes, others comment on love for or erotic relationships with athletes. Still others link paiderastia and sport for metaphorical purposes, betraying how habitual the connection was in the Greek imaginary.

The dating of the collection of poetry attributed to Theognis of Megara is (like its authorship) a complicated issue, but two lines attributed to Theognis that were probably written in the middle of the sixth century seem to be the earliest poem to make the connection between paiderastia and sport: “Happy is he who, when in love, exercises in the nude and, when he goes home, / Sleeps all day with a beautiful boy” (1335–6).7

Two sixth-century poets, Ibycus and Anacreon, connect eros (though not specifically paiderastia) and sport for metaphorical purposes. Ibycus (Fragment 287 PMG), when in love, compares himself to an old racehorse forced to race again. Anacreon compares himself to a charioteer (Fragment 360 PMG) and uses boxing with Eros (Fragment 396 PMG) as a metaphor for resisting the power of love.

In the poetry of Pindar, who in the early decades of the fifth century wrote numerous odes praising athletic victors (see Chapter 4), the athlete’s beauty is a constant theme, particularly with boy victors. At Olympian 8.19, Olympian 9.94, and Isthmian 7.22, he lauds victors as beautiful and their deeds as worthy of their beauty. At Pythian 9.96–100 and Pythian 10.55–60, he comments on their attractiveness to spectators (including women). This theme is perhaps most eloquently expressed at Olympian 10.99–105:

I have praised the lovely son of Archestratos,

Whom I saw conquering by might of hand

At that time

By the Olympian altar,

Beautiful in form

And mixed with the prime of life which once

Kept shameless death from Ganymede, with the help of the Cyprus-born

[Aphrodite]. (trans. N. Nicholson)

The relationship between paiderastia and sport appears repeatedly in the work of Aristophanes, Plato, and Xenophon. Indeed, as is true for many aspects of life and culture, we have more evidence from Classical Athens than from any other time and place in Greek history for this connection. In Aristophanes’ Clouds (973–6), when the Better Argument wants to praise the modesty of the boys of the past (or rather their modest acknowledgment of the desires of their erastai), he does so by praising their behavior (973) “at the [athletic] trainer’s.” At Birds 137–42, the character Euelpides, a kind of Athenian everyman, describes a fantasy Athens where, when he meets a boy leaving the gymnasion, he can make passes at him, hug him, and kiss him, with encouragement from the boy’s father. At both Peace 762–3 and Wasps 1023–5, Aristophanes claims that when he won prizes for his comedies, he did not become conceited and go through palaistrai (wrestling schools, see Chapter 19) trying to pick up boys. The scholia (ancient footnotes) tell us that this is a response to Eupolis, another comic writer, who in his comedy Autolykos said that he did this. This suggests that cruising gymnasia for boys was common, though perhaps it did not conform to an idealized style of paiderastia.

The situation is similar in the work of Plato. Plato’s Charmides (153d–4a), Euthydemus (273a–4c), and Lysis (204b–7c) are all set in gymnasia or palaistrai. One beautiful boy is central to the beginning of each dialogue: in the Euthydemus Kleinias, in the other two dialogues the youths for whom they are named. Lysis is being courted by a youth named Hippothales; Kleinias and Charmides are both followed by a throng of would-be erastai. Indeed, Socrates remarks that not only the adult men were excited by Charmides, but even the other boys, who gazed at him fixedly, as though he were a statue (153c–d).

Xenophon’s Symposium provides a very modest portrait of an erastes–eromenos relationship with an athletic dimension. The dialogue takes place at a dinner given by the erastes, Kallias, after his eromenos Autolykos – the subject of Eupolis’s comedy – won a victory in the pankration. The modesty of this relationship is clearly symbolized by the presence of Autolykos’s father at the dinner. Socrates praises Kallias for loving a boy who is so desirous of glory that he has labored and suffered for the goal of winning the pankration (8.37).

Interestingly, it is Plato who shows us how courtship in the gymnasion might proceed toward consummation. At Phaedrus 255b–6d, it is touching in the gymnasion and elsewhere that releases the flow of himeros (desire) on the erastes that eventually causes the eromenos to believe that he too feels eros, so that both partners desire to touch, kiss, and lie down together, and in some cases (the second best) they yield to the desire for sex. Moreover, at Symposium 217c, Alcibiades recounts how in his attempt to seduce Socrates, he invited him to wrestle with him “with no-one else present” but “got nothing more” from it, thus making clear that an eromenos, if he wrestled alone with his erastes, would normally expect the erastes to try to turn their physical contact into sexual contact. The Laws too connects paiderastia and sport; the Athenian speaker, who disapproves of male–male love, blames its existence on Crete and Sparta and “other cities that are especially devoted to gymnasia” (636b–c).

The connection between paiderastia and sport remains a leitmotif of Greek culture until the end of pagan antiquity. In one of the poems of Theocritus (23.58–60), written in the third century, a statue of Eros in a gymnasion falls on a boy who cruelly rejected his erastes and kills him in punishment. The gymnasion and the attractiveness of athletes are recurrent themes in the Hellenistic (323–31) and Roman-era (31 BCE–476 CE) elegies collected in Book 12 of the Palatine Anthology. At 12.123, for instance, the (anonymous) poet speaks of kissing a boy boxer with blood streaming down his face, and at 12.192, attributed to Strato, the poet praises the attractiveness of boys from the gymnasion, covered in dust and glistening with oil. Another theme among poets of the Roman period is the sexual opportunities available (perhaps in the poet’s fantasy) to boys’ trainers (see, for example, 12.34, 12.222). Paiderastia is associated with the gymnasion and athletic nudity in Plutarch’s Erotic Dialogue (751f) of the late first or early second century CE, as it also is in Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations (4.70). Boys’ athletic pastimes and bodies are key points in the defense of paiderastia in Achilles Tatius’s Leukippe and Kleitophon (2.38) and the Erotes attributed to Lucian (45–6), both of which works seem to date to the second century CE.

It is tempting to regard the statues of nude, athletic youths of eromenos age (kouroi), that Greek sculptors produced starting in the seventh century, as further evidence for the connection of paiderastia and sport. In fact, however, with very few exceptions, no specific attributes connect kouroi that were produced in the Archaic period (700–480) either to sport or to pederastic love. On the other hand, Deborah Steiner (1998: 133–5; cf. Ferrari 1990 and 2002: 54–6, 72–81) has made the interesting suggestion that the many fifth-century statues of athletes crowning themselves with their victor’s wreaths are not only specifically athletic but also specifically erotic. In her view, by representing these youths at the moment of victory, the sculptor has shown them at the height of their erotic attractiveness. This is further heightened by their downcast gazes, which represent the aidos (sense of modesty) central to the behavior and identity of the ideal eromenos. This argument could also be applied to Lysippos’s famous Apoxyomenos, a fourth-century sculpture of an athlete scraping himself clean of oil and dust. Lysippos chose to portray the athlete at a moment that, in vase painting, seems to be among the highpoints of the attractiveness of eromenoi, as is demonstrated by Figure 15.1, a courtship scene in which a bearded erastes offers his nude eromenos a courting gift of a strigil (a bronze scraper for removing oil and dust after exercise) (cf. New York 1979.11.9, a red-figure kylix by Makron, side B, on which see Lear and Cantarella 2008: 91–5 and fig. 2.16b).

A number of literary sources (e.g., Aristophanes Acharnians 142–4 and Wasps 97–9; Palatine Anthology 12.41, 12.129, and 12.130; and pseudo-Lucian Erotes 16) tell us that the Greeks customarily wrote the names of youths they found attractive on walls, trees, and other surfaces, paired with the adjective kalos (beautiful), producing what we now call kalos inscriptions. Such graffiti have been found by archaeologists in a number of places, including Nemea, where nine were found in the tunnel connecting the apodyterion (locker room) to the stadium (Miller 2001: 86–9). As this space was largely reserved for athletes, these were almost certainly written by them, and given the general Greek attitude toward the attractiveness of athletes, they seem most likely to refer to other athletes (perhaps ones who had just left the tunnel to compete). They thus may constitute a rare piece of evidence for the attractiveness of athletes to other athletes.

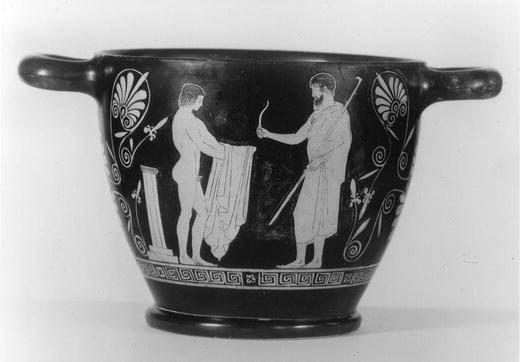

Kalos inscriptions also occur in vase painting. Vase painters began including kalos inscriptions in their work by the middle of the sixth century, and they were extremely common in vase painting of the later sixth and early fifth centuries, with a few appearing as late as the 420s. Originally these followed the formula of real graffiti and referred to a youth by name; around nine hundred such inscriptions are preserved. At some point, however, vase painters developed their own version of these inscriptions, praising the beauty of an unnamed youth with the words ho pais kalos (the boy is beautiful). There are thousands of ho pais kalos inscriptions; indeed, they are so common that it is impossible to estimate their number reliably.8 Like inscriptions with names, these can at times appear on vases without an image of a youth.9 The majority, however, appear above an image of an attractive youth, as in Figure 15.2, another courtship scene, in which a bearded erastes offers a sack to a seated eromenos, who is identified as an athlete by the sponge and aryballos (a small vase for holding oil used during and after exercise) to the right of the couple. Indeed, so many such inscriptions appear above the image of a young athlete that this is the most common pederastically inflected motif in vase painting. Clearly these images demonstrate or even embody the strong link between paiderastia and sport.

Figure 15.1 Athenian skyphos showing a courtship scene, attributed to the Lewis Painter, c.460BCE. Source: Copyright © Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California. Catalog No. 8-4581.

The iconography of vase painting also often makes clear links between paiderastia and sport. Much as kalos inscriptions render explicit the erotic element in the portrayal of athletes, so various elements in pederastic scenes render explicit their connections to sport. Again, Figure 15.2 provides an example: the gym kit to the couple’s right (along with a net bag for holding astragaloi, knucklebones with which the Greeks played a game like jacks) sets the scene in a gymnasion, or if one reads the scene more symbolically than dramatically, in the context of sport. The contents of the sack that the erastes offers the eromenos will be discussed later in this essay. In other courting-gift scenes, however, the gift can be explicitly connected to the gymnasion (e.g., the strigil in Figure 15.1). Other elements in the scenes can also emphasize the link between paiderastia and sport, as does the terma (goalpost from the end of a stadium) to the left of the eromenos in Figure 15.1 (cf. Mykonos 966, a red-figure pelike by the Triptolemos Painter, on which see Lear and Cantarella 2008: 45–6 and fig. 1.6).

Indeed one could argue that the youth in Figure 15.1 embodies the connection between athletics and paiderastia – or rather, the merger of the figures of the eromenos and the athlete. On the one hand, he is a compliant eromenos: he is preparing to accept and to use the strigil his erastes offers (by contrast with the eromenos on the other side of the vase, who is refusing the gift offered to him with petulant gestures), and thereby allowing his erastes to see his naked body. On the other hand, he is simultaneously, by the same gesture and token, an athlete cleaning himself, with the terma that symbolizes his athletic activities right behind him. The scene combines the inside and outside of the gymnasion as the athlete/eromenos blends the two sides of his life as a beautiful youth.10

Figure 15.2 Athenian kylix showing courtship scene, attributed to Douris, c.480–470BCE.Source: © 2013 Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

It is a commonplace of scholarship on paiderastia that pederastic scenes disappear from vase painting in the middle of the fifth century. This is in fact not true. Vase painting of the late fifth and fourth centuries no longer represents sex explicitly, whether heterosexual or pederastic, but pederastic courtship scenes remain extremely common. Interestingly, in this later period, the gifts offered in such scenes are increasingly connected to the gymnasion. While erastai in earlier vase painting favor hares and fighting cocks as courting gifts, the most common gifts in later scenes are discuses and strigils.11

The vase painters of this later period also developed a new way of representing erotic scenes, through the presence of the god Eros. A number of such scenes take place in the gymnasion, where Eros is often flying over (or from or to) an altar, possibly his own. In several such scenes, he seizes a youth, perhaps forcing him to accept the power of Eros, presumably in the form of love for an erastes or for a fellow young athlete. In one typical scene (Villa Giulia 47214, a red-figure neck amphora by the Flying Angel Painter, on which see Lear and Cantarella 2008: 162 and fig. 4.22), Eros, with a stick or goad in his hand, arises from his altar and chases a fleeing youth.

Given the strong link between sport and paiderastia, it might strike the reader as surprising that this connection is not the subject of a great deal of scholarly interest. In fact, however, this is unsurprising; this link was not “problematized” in Greek culture. It was taken for granted by the Greeks and is taken for granted by modern scholars. Nonetheless, a few questions about it have arisen in Classical scholarship.

One of these questions pertains to the origins of paiderastia. As is the case with athletics and athletic nudity, the discovery of tribal initiation rites in the early twentieth century CE led a number of scholars to view paiderastia as deriving from such rites in Greek prehistory or as representing something tantamount to them even in the historic period, at least in such places as Crete and Sparta.12 This idea relies heavily on ethnographic parallels from tribes in Melanesia in the South Pacific that practice initiation rites with a pederastic component. There is in fact some slight evidence in favor of this view, but there is no evidence to exclude any of the other common views of the origins of paiderastia (such as the idea voiced by Aristotle at Politics 1272a that it derived from an attempt to control population growth, or the view that it developed out of intense bonding in military units).13

Some scholars have also seen Greek myths such as those about the relationships between Poseidon and Pelops, Chrysippos and Laios, and Hyakinthos and Apollo as proving that the connection between paiderastia and Greek athletics derived from prehistoric initiation rites. However, as other scholars starting with Dover (1988: 126–9) have pointed out, the problem with such arguments is that Greek myths were highly mutable. There is no evidence that these stories date from prehistoric times in exactly this form; indeed, such evidence as there is speaks against this possibility. For the Chrysippos story we simply have no evidence prior to the fragments of Euripides’ play Chrysippos, from the fifth century. In other cases, we have evidence that the pederastic versions of the story were innovations. Pindar seems to take responsibility for the pederastic version of the Pelops story (Olympian 1.37–45), and while the Hyakinthos story appears as a full-blown pederastic love triangle in a vase painting of the middle of the fifth century (Lear and Cantarella 2008: 152–4 and fig. 4.13), our earliest source, the poet Hesiod (Fragment 171.6–8 Merkelbach-West), presents the story with no erotic element. Thus it is best to disregard myth when discussing the origins of paiderastia, athletics, and the link between them.14

In any case, the evidence of the Homeric epics suggests that neither paiderastia nor athletic nudity were widely practiced in Greece before the seventh century. Both instead seem to be new developments of the Archaic period and thus to be more probably connected to the intense homosociality of the early polis (city-state) than to tribal rites. A persistent tradition in Greek sources connects the development of these customs to Crete or Sparta, or at least the “Dorian” poleis. Given Sparta’s prestige in Archaic Greece, it thus seems possible that the two were aspects of a cultural package associated with Sparta that spread to other poleis in the Archaic period.

A second question concerns the role of erastai in the athletic training of their eromenoi. Two prominent scholars have in recent years argued that they may at times have had a more direct hand in it than has traditionally been supposed. Nick Fisher (1998, in particular 96–8, also 2006: 243–4) has argued that, given the large numbers of athletes involved in such festivals as the Panathenaic Games in Athens, it is unlikely that all were from elite families. Instead, he proposes that some were from less wealthy families and were sponsored, in their athletic training, by wealthier erastai. There is little direct evidence for such relationships, but the argument is still (in this writer’s view) plausible.

Among other things, this hypothesis led Fisher (1998: 97) to make an interesting suggestion about a thorny issue in the iconography of pederastic scenes in vase painting. In a number of courting-gift scenes, as in Figure 15.2, the gift consists of a small sack. There is some evidence that such sacks are intended as money sacks. The argument has also been made that they contain astragaloi, but vase painters often make a clear contrast between these sacks and astragalos bags, as the painter of Figure 15.2 has between the sack in the hand of the erastes and the bag on the wall (which is of a type often clearly portrayed as containing astragaloi). Given the disapproval expressed widely in Greek culture of eromenoi receiving money from their erastai (see, for example, Aristophanes Wealth 249–59; Plato Symposium 184a–b; Aeschines Against Timarchos 137), this would seem to suggest that the youths in these scenes are not to be approved of. Yet often, as in Figure 15.2, they are otherwise portrayed with all the conventions of praiseworthy eromenoi and athletes. As a result, these scenes are the subject of one of the most heated controversies in the area of erotic vase painting.15 Fisher, however, on the basis of his theory proposes that scenes with gifts of money bags represent an erastes offering to support the athletic training of his eromenos. There is no direct sign of this in the scenes, but it is a plausible reading of them and would explain how vase painting could portray youths receiving money from their erastai without any hint of disapprobation.

A similar suggestion has been made by Thomas Hubbard, who argues that some elite adult athletes may have served directly as trainers for their eromenoi (Hubbard 2005). Again, the evidence for this theory is tenuous. Pindar at Olympian 10.16–19 makes the unusual gesture of referring to the trainer of the young athlete whom the ode praises by name and also compares athlete and trainer to Achilles and Patroklos, generally regarded in Archaic and Classical Greece as a pederastic couple.16 All of this might suggest that the trainer was of elite status, because only in this case could he be a worthy erastes for such an eromenos. The other evidence is, however, less certain. Indeed, on the whole, vase painting would seem to suggest the opposite, as erastai and trainers, although of the same age-types and therefore iconographically similar, are generally clearly distinguished by their attributes – in the case of erastai gifts and other props or gestures connected with courtship, in that of trainers, their trainer’s rods. To this writer’s knowledge, no single figure in Athenian vase painting has both types of attribute. Nonetheless, as with Fisher’s theory, Hubbard’s is not implausible. Greeks of elite status generally did not work for pay, but as some of the sophists seem to have been exceptions to this rule, there is no reason why some trainers could not also have been. However, they are more likely to have trained their charges without pay, for a combination of glory and love.17

A third question has to do with the practice known as “infibulation.” A number of vase paintings show Greek athletes either binding their foreskin or penis with a cord or with their foreskin or penis so bound18; this binding also appears in some scenes of adult revelers, and even satyrs. In an Etruscan tomb painting (from the Tomb of the Monkey), a group of athletes has bound their penises to a belt around their waists (see Scanlon 2002: 235, figs. 8–5). There are no textual references to this custom in Archaic or Classical Greek sources,19 and as a result we are uncertain as to the details. We do not know how common it was, if it was largely an athletic practice or a more widespread one, or how foreskins/penises were actually bound. Is the Etruscan wall painting, for instance, a more complete rendering of the practice, or does it portray an Etruscan variation? Nor do we know why this was done. It seems unlikely that it can have served to protect the penis from any of the dangers of nude athletics, on the model of a modern jockstrap, or to improve athletic performance. If either of these were the purpose, then the testicles would have been bound in some way as well (Sweet 1985: 47–9). A number of scholars (for instance Scanlon 2002: 235) have suggested that it may have served to prevent erections caused by the attractions of other athletes. Yet it seems unlikely that athletes can often have got erections while engaged in sport, with its discomforts (although Alcibiades’ attempt to seduce Socrates by wrestling with him suggests that wrestling in particular may have been regarded as potentially sexually exciting). Perhaps the best interpretation that has been suggested (Sansone 1988: 120) is that the custom was symbolic of sexual restraint, a virtue often praised in Greek writing, sometimes with particular reference to athletes (see, for instance, Plato Laws 839e–40b). This explanation has the advantage of applying equally to the athletes and the nonathletes portrayed as bound. It even suggests how its appearance in a satyr scene may have functioned as a joke.

ABBREVIATIONS

PMG = D. L. Page, Poetae Melici Graeci

NOTES

1 For the worship of Eros in other gymnasia, see Athenaeus 13.561f–2a for Samos and Pausanias 6.23.3 for Elis. Note also that an athletic festival, called the Erotidia, was held in honor of Eros in Thespiai (in Boeotia), Eros’s most important cult center; this festival serves as the setting for Plutarch’s Erotic Dialogue.

2 See Scanlon 2002: 122–7 for the idea that female athletics, when and where they were practiced, also had an erotic aspect.

3 In the interests of brevity, legal codes are not discussed here, though sources including Aeschines’ Against Timarchos and the law from Beroia, discussed in Chapter 22 in this volume, offer important information on paiderastia and sport.

4 The best-known recounting of this myth can be found in Pindar Olympian 1. For a full discussion of the other relevant sources, see Weiler 1974: 209–17.

5 The relevant sources are listed and briefly discussed in Scanlon 2002: 73–4.

6 All dates are BCE unless otherwise indicated.

7 On Theognis, see Figueira and Nagy 1985 and Selle 2008. All translations of ancient sources are my own.

8 Lissarrague 1999: 365 cites figures from the great nineteenth-century CE collector, Prince Lucien Bonaparte, that would indicate that there may be as many as twenty thousand, though, as he says, “this very approximate calculation needs to be checked against other samples.”

9 See Lear and Cantarella 2008: 164–5 and 171–2 for discussion and 171 n. 18 for bibliography on this issue.

10 There are many other examples of such athletes/eromenoi; see for instance the beribboned young athlete on Boston 10.178 (a red-figure Panathenaic amphora by the Kleophrades Painter, on which see Lear and Cantarella 2008: 96–7 and fig. 2.18), who carries an aryballos on his left arm and on his right a live hare, the most common pederastic courtship gift in vase painting of this period.

11 See for example, side B of Louvre G 521 (a red-figure bell krater by the Painter of Louvre G 521, on which see Lear and Cantarella 2008: 178–9 and fig. 4.21b), where two erastai each offer a young athlete a strigil.

12 This idea was first voiced by Bethe in 1907. It is generally more popular in continental Europe than in the United Kingdom and North America. For the continental perspective, see Jeanmaire 1939; Brelich 1969; Bremmer 1980; Patzer 1982; and Sergent 1986 (1984). For more skeptical views, see Dover 1988 and Percy 1996: 17.

13 See Lear 2013 for discussion of this issue and bibliography.

14 See Scanlon 2002: 64–97 for extensive (and skeptical) discussion of the view that athletic nudity and paiderastia are related elements deriving from initiation rites.

15 See Lear and Cantarella 2008: 79–86 for discussion and bibliography.

16 See, for instance, Aeschylus Fragments 135 and 136 Radt and Plato Symposium 180a.

17 On the Sophists’ acceptance of fees from their students, see Tell 2011: 39–60.

18 See, for example, Side A of Berlin 2180 (a red-figure kalyx krater by Euphronios), illustrated as fig. 5.1a in Lear and Cantarella 2008: 166, and Scanlon 2002: 234–6 for discussion and bibliography.

19 Late Antique dictionaries give us a name for the binding, kynodesme (dog’s leash) (see, for example, Pollux 2.4.171), although most modern writers refer to the practice as infibulation, a word which actually refers to a Roman practice of closing the foreskin with a pin (fibula).

REFERENCES

Bethe, E. 1907. “Die dorische Knabenliebe: Ihre Ethik und ihre Idee.” Rheinisches Museum 62: 438–75.

Brelich, A. 1969. Paides e Parthenoi. Rome.

Bremmer, J. 1980. “An Enigmatic Indo-European Rite: Paederasty.” Arethusa 13: 279–98.

Cartledge, P., P. Millett, and S. von Reden, eds. 1998. Kosmos: Essays in Order, Conflict and Community in Classical Athens. Cambridge.

Crowther, N. 2004. Athletika: Studies on the Olympic Games and Greek Athletics. Hildesheim.

Dover, K. J. 1988. The Greeks and Their Legacy. Oxford.

Dover, K. J. 1989. Greek Homosexuality. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA.

Ferrari, G. 1990. “Figures of Speech: The Picture of Aidos.” Métis 5: 185–204.

Ferrari, G. 2002. Figures of Speech: Men and Maidens in Ancient Greece. Chicago.

Figueira, T. and G. Nagy, eds. 1985. Theognis of Megara: Poetry and the Polis. Baltimore.

Fisher, N. 1998. “Gymnasia and the Democratic Values of Leisure.” In P. Cartledge, P. Millett, and S. von Reden, eds., 84–104.

Fisher, N. 2006. “The Pleasure of Reciprocity: ‘Charis’ and the Athletic Body in Pindar.” In F. Prost and J. Wilgaux, eds., 227–45.

Goldhill, S. and R. Osborne, eds. 1999. Performance Culture and Athenian Democracy. Cambridge.

Guttmann, A. 1996. The Erotic in Sports. New York.

Hubbard, T. 2003. Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents. Berkeley.

Hubbard, T. 2005. “Pindar’s ‘Tenth Olympian’ and Athlete–Trainer Pederasty.” In B. Verstraete and V. Provencal, eds., 137–71.

Hubbard, T., ed. 2013. A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities. Malden, MA.

Jeanmaire, H. 1939. Couroi et courètes: Essai sur l’education spartiate et sur les rites d’adolescence dans l’antiquité hellénique. Lille.

Lear, A. 2013. “Ancient Greek Pederasty: An Introduction.” In T. Hubbard, ed.

Lear, A. and E. Cantarella. 2008. Images of Ancient Greek Pederasty: Boys Were Their Gods. London.

Lissarrague, F. 1999. “Publicity and Performance: Kalos Inscriptions in Attic Vase Painting.” In S. Goldhill and R. Osborne, eds., 359–73.

Miller, S. 2001. Excavations at Nemea II: The Early Hellenistic Stadium. Berkeley.

Patzer, H. 1982. Die griechische Knabenliebe. Stuttgart.

Percy, W. A. 1996. Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece. Urbana, IL.

Prost, F. and J. Wilgaux, eds. 2006. Penser et représenter le corps dans l’Antiquité. Rennes.

Sansone, D. 1988. Greek Athletics and the Genesis of Sport. Berkeley.

Scanlon, T. 2002. Eros and Greek Athletics. Oxford.

Selle, H. 2008. Theognis und die Theognidea. Berlin.

Sergent, B. 1986 (1984). Homosexuality in Greek Myth. Boston.

Steiner, D. 1998. “Moving Images: Fifth-Century Victory Monuments and the Athlete’s Allure.” Classical Antiquity 17: 123–49.

Sweet, W. 1985. “Protection of the Genitals in Greek Athletics.” Ancient World 11: 43–52.

Tell, H. 2011. Plato’s Counterfeit Sophists. Cambridge, MA.

Verstraete, B. and V. Provencal, eds. 2005. Same-sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West. Binghamton, NY.

Weiler, I. 1974. Der Agon im Mythos: Zur Einstellung der Griechen zum Wettkampf. Darmstadt.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

The relationship between athletics and eros, in particular pederastic eros, is a common theme in Greek literature and art. It is also frequently mentioned in modern scholarship (see for instance Dover 1988, in particular pp. 54–5 and 69–70), but there is little work directly on this topic, probably because the link is so firmly established that it seems to require little comment. The main current treatment of the theme is Scanlon 2002, see in particular chapters 3 (pp. 64–97) and 8 (pp. 199–273), “Athletics, Initiation, and Pederasty” and “Eros and Greek Athletics” respectively. The relevant literary evidence is collected in Hubbard 2003. Lear and Cantarella (2008) contains extensive discussion of the artistic evidence. There are also articles on specific aspects of the issue. Steiner (1998) points to interesting parallels between the representation of athletes in poetry and the visual arts. Fisher (1998 and 2006) has questioned the traditional view of athletics as an exclusively elite activity by suggesting that erastai from the elite may have sponsored the athletic careers of nonelite eromenoi and thereby facilitated their rise into the elite. Hubbard (2005) has made a different argument on a similar theme, suggesting that some elite erastai may have served as athletic trainers for their eromenoi.