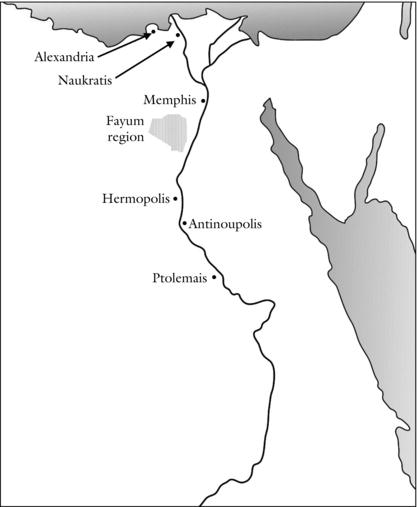

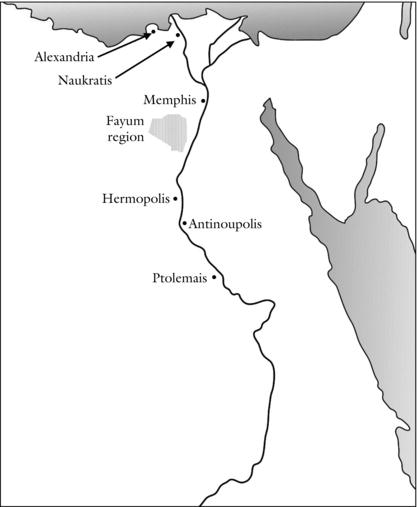

Map 23.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered Egypt. From a strictly territorial perspective this immediately made Egypt part of the Greek world. The infiltration of Greek culture naturally went at a slower pace. One aspect of Greek culture that found its way into Egypt was sport.

Sport was of course not new in Egypt. Several sports known in Greece, such as running, wrestling, and boxing, had developed their own independent traditions in Egypt (Decker 2006: 75–93). This essay is not, however, about individual sports and their regional variations, but about the introduction of an institutionalized form of sport and its place in an evolving society. By Greek sport as an institution, I mean the set of physical activities that was taught to young men in gymnasia in order to imbue them with specific cultural values, and which made up the program of agones, that is, contests with athletic, equestrian, and/or artistic events which were a part of recurring, typically quadrennial, religious festivals organized by Greek cities in honor of a god.

This essay will deal with two opposed but connected questions: what drew the population of Egypt, particularly Greek immigrants, to sport and what obstacles complicated its introduction? I will focus on three key periods: (1) the Early Ptolemaic Kingdom (c.323–c.200 BCE), when Greek sport as an institution was first established in Egypt; (2) the later Hellenistic and Early Roman periods (c.100 BCE–c.200 CE), when membership in a gymnasion became a legal requirement for elite status; and (3) the third century CE, when metropoleis (capitals of nomes) achieved the legal status of cities, which significantly enhanced their ability to organize athletic contests.

Alexander and his immediate successor as ruler of Egypt, Ptolemy I, preserved the traditional administrative division of Egypt into roughly forty districts (nomes), each with its own capital, which the Greeks called nomoi and metropoleis, respectively. The metropoleis were not autonomous political entities like Greek city-states (poleis); their inhabitants were governed directly by the royal administration. In other parts of the territories in the Near East conquered by Alexander, the rulers of newly established states such as the Seleucid Kingdom founded new or refounded old urban centers as poleis, which, although part of a kingdom, could theoretically act independently and which granted citizenship to their residents. In Egypt, however, the number of poleis remained limited to three: the old Greek trading post Naukratis, the new capital Alexandria, and Ptolemais, a new city in Upper Egypt founded by Ptolemy I (see Map 23.1 for the locations of key sites mentioned in this essay).

Alexander’s conquest marked the beginning of large-scale Greek immigration to Egypt. Ptolemy came from Macedonia, and he and his descendants employed an army largely made up of men from various parts of the Greek world. There was, therefore, particularly in the early decades of Ptolemaic rule, a steady influx into Egypt of Greeks who came to take up (well recompensed) positions in the army. Other Greeks were attracted to Egypt because of economic prospects.

Map 23.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

These Greek immigrants formed the upper layers of early Ptolemaic society. Soldiers and officers received a plot of land in the chora, the countryside of Egypt, so most of them settled in villages or metropoleis and not in one of the three poleis. To enjoy privileges such as tax reduction or exemption, they had to identify themselves as Greeks. These villages and metropoleis were not legally capable of granting citizenship to their residents, and so Greek immigrants were identified by reference to the polis from which they or their forefathers had emigrated. These designations, called ethnika, were used as identifiers for more than two centuries, and individuals whose families had resided in Egypt for generations continued to use ethnika inherited from their ancestors (La’da 2002).

That metropoleis were not poleis hindered the introduction of sport. The procedure for the introduction of an agon in Greek poleis outside of Egypt during the Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE) is known from inscriptions (e.g., IvM 16, FD 3.3 215). The city council decided to establish the contest and determined practicalities, such as date, age categories, procedures for the appointment of officials, and so on. It then sent out ambassadors to other communities to publicly announce its intention to hold agones on a particular date and to invite participation by athletes, who would compete in the games, and by official delegations from other communities, which would attend the religious ceremonies that were held during the games. Even if the initiative for a new contest might come from a Hellenistic king, the practical organization was still in the hands of the city. During the festival, the city expressed its central importance with the special place civic groups such as magistrates, priests, and ephebes received in the procession.

While the poleis of Egypt could have agones like any other Greek city, the Egyptian metropoleis lacked the institutional apparatus for the organization and upkeep of their own games. This had the effect of impeding the creation of local agones in Ptolemaic Egypt.

Nonetheless, sport flourished in Ptolemaic Egypt, in large part because the first four Ptolemaic kings (Ptolemy I–IV) actively sought to promote participation in the major athletic contests in the Greek homeland by Greeks residents in Egypt and founded contests in Alexandria. In these, as in other respects, they followed the example of their Macedonian predecessors. Philip won several equestrian events at Olympia, and Alexander organized many games during his expedition (see Chapter 22 in this volume).

A recently discovered collection of epigrams shows that in the Early Hellenistic period members of the Ptolemaic court were particularly active in equestrian competitions at major games at sites in the Greek homeland such as Olympia and Delphi. A papyrus roll, which was discarded and reused as mummy cartonnage, contains 112 epigrams that were written by Posidippos of Pella, a poet who was active in the first half of the third century BCE and who spent much of his life at the courts of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II. Most of these epigrams were unknown to modern-day scholars before the publication of the papyrus in 2001. One section of the collection comprises 18 poems, called hippika, that celebrate victories in equestrian contests, and these poems added substantially to our knowledge of the sporting ambitions of members of the Ptolemaic court. Posidippos’s hippika, like a previously known victory ode for Queen Berenike II written by the poet Callimachus, were commissioned to promote the Ptolemaic penchant for victory. The investment in racehorses and in publicity for the victories served a clear goal: the promotion of an “image of power” in the Greek world.1

Members of the royal family did not participate personally in athletic events, possibly because Alexander, whom they took as their model, reputedly found these events too lowly for a king (Plutarch Alexander 4.10), but no doubt mainly because they did not have the talent. In ancient Greek equestrian competitions, it was typically the case that chariots were driven and horses were ridden by hirelings, while virtually all the fruits of victory accrued to the horses’ owners (see Nicholson 2005 for further discussion). The Ptolemies did, however, stimulate their subjects to compete, again in order to demonstrate the strength of Egypt. Polybius (5.64.4–7) reports that Ptolemy IV (ruled 221–205 BCE) showed great esteem for Polykrates, who immigrated to Egypt from the polis of Argos and took up an important post in the Ptolemaic army. Ptolemy was impressed by Polykrates’ noble lineage and wealth and especially by the reputation of his father Mnasiadas, who was a famous athlete. Ptolemy went so far as to appoint Mnasiadas eponymous priest of Alexander, the highest honorary official in Alexandria (Clarysse and van der Veken 1983: 14). In another passage (27.9), Polybius tells how Ptolemy IV subsidized the training of a talented boxer in order to send him to Greece to compete in high-level athletic contests. Against this background, it is not surprising that competitors from Egypt did remarkably well in major athletic competitions in Greece in the third century BCE (Remijsen 2009). Unlike competitors from new Greek cities in Asia, Alexandrians (the only identifiable inhabitants of Egypt) are clearly present in lists of athletes who won victories at the major Greek athletic festivals in the third century BCE.

The Ptolemies, particularly Ptolemy II (ruled 283–246 BCE), also founded agones in Egypt. The Ptolemaia, a quadrennial religious festival that included athletic contests, was established in 279 by Ptolemy II in honor of his deceased father. It was held every four years in a sacred place called Hiera Nesos not far from Alexandria (PSI 4.364).2 Ptolemy had high ambitions for the athletic contests at the Ptolemaia; he wanted them to become equal to the Olympic Games and for this purpose coined the term “isolympic,” a word that outlived the Ptolemaia for many centuries. To obtain this special status, he adapted the traditional custom of sending out representatives to other cities to announce the intent to hold an agon. Ptolemies’ representatives did something new by requesting that the cities they visited grant victors in the Ptolemaia the same rewards as victors in the Olympics (Syll.3 390, CID 4.40).

This innovation inspired the development of a procedure for elevating the status of athletic contests, a procedure that was subsequently employed by the organizers of contests other than those of the Ptolemaia. It will be helpful to briefly review here the relevant terminology, which will be employed in this essay (on the procedures and terminology, also see Chapter 6). Starting in the sixth century BCE, the Olympic, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games became the four most prestigious contests in the Greek world. In literary works of the fourth century, these games are sometimes characterized as stephanites (stephanitic, “games giving a crown”), because the prizes awarded to victors at the games themselves were crowns made from sacred plants, such as the crown of olive awarded at Olympia. The communities from which those victors came habitually gave them further rewards with substantial monetary value. The prestige of the Olympic, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games was such that they were the stephanitic games par excellence, though there was no particular reason that the term could not have been applied to less well known contests that also only gave crowns as prizes.

In the Hellenistic period, as many new athletic contests were founded in the rapidly expanding Greek world, the term “stephanitic” was also used to describe athletic contests organized in such a way that victors received from their home cities the same sort of rewards they received for winning at the Olympic, Pythian, Isthmian, or Nemean Games. This terminology can be confusing because some of these new games possibly offered prizes other than crowns.

In order to become stephanitic in this sense (that is as a technical categorizing term rather than as a literary description), the community responsible for organizing the athletic contest in question had to send out ambassadors to other communities in order to request that they recognize the games as stephanitic and reward victors accordingly. As a result, a set of games organized by Community A could be stephanitic as far as Community B was concerned, but not stephanitic as far as Community C was concerned.

Although the introduction of the Ptolemaia predates the new use of the term “stephanitic,” it did inspire it. When Ptolemy II persuaded many communities to recognize the Ptolemaia as isolympic, which meant that those communities rewarded any of their citizens who won a victory at the Ptolemaia in the same fashion that they would reward an Olympic victor, other cities followed his example and had their games recognized as isopythian, or isonemean. By the mid-third century, “stephanitic” came into use as an umbrella term for all these games for which victors were rewarded in their hometown. As the term “stephanitic” was applied to a much larger number of games than in the fourth century, a new word was needed to designate the “Big Four,” and, starting in the second century BCE, the cycle of these four games, which were timed to never coincide with each other, was called the periodos (“the circuit”).

One final linguistic nuance is worthy of brief mention. Starting in the late second century BCE the word hieros (“sacred”) also began to be used to describe contests that were stephanitic, with no evident difference in meaning. For a time the words were used interchangeably (and sometimes together, which was redundant but perhaps impressive to some); eventually hieros became the standard term. This term too is potentially confusing because in a sense most if not all Greek athletic contests, which were typically held as part of religious festivals, were sacred. One must, therefore, bear in mind that the terms stephanitic or sacred, when applied to athletic contests founded in the Hellenistic period and later, and when used properly, are technical terms with specific meanings that are less obvious than they might appear.3

Although several states that were allied with Ptolemy accepted the Ptolemaia’s isolympic status, he did not actually succeed in making the Ptolemaia into a contest that enjoyed the same reputation as the major athletic games such as the Olympics. The Ptolemaia are only attested in the third century BCE, and the level of competition was not very high. A professional actor from the minor state of Tegea even managed to win the boxing competition (Syll.3 1080). Although athletes from the periphery traveled to the Greek mainland to compete at sites such as Olympia, the reverse did not occur with any frequency in the third century. The cosmopolitan athlete, who traveled throughout the Greek world to participate in contests, only became common in the first century BCE.

Less than 10 years after founding the Ptolemaia, Ptolemy II, having married his sister Arsinoë and deified himself and his wife as the Sibling Gods, established another agonistic festival, this one called the Theadelpheia. Ambassadors from other cities made a single trip for the Ptolemaia and the Theadelpheia, which suggests that the contest of the Theadelpheia was quadrennial as well. Like the Ptolemaia, the Theadelpheia probably attracted mostly local athletes, alongside some visitors from cities allied with the Ptolemies (SEG 36.1218; IvO 188).

A third important contest was the Basileia. These games were probably not a direct continuation of the ad hoc games Alexander dedicated to Zeus Basileus in Memphis (Arrian Anabasis 3.5.2), but may have been inspired by those games. Details of the organization of the Basileia suggest that they were introduced after the Ptolemaia. The contest was held on the eighteenth day of the Egyptian month of Dystros, which was Ptolemy II’s birthday and also the day on which, at age 24, he became co-ruler of Egypt. The birthday was of course an annual event, but it is not clear whether it was celebrated annually with an agon.

There has been some confusion as to whether there was a single Basileia festival held in Alexandria or whether the festival was celebrated in multiple places in Egypt on the same day. An inscription found in Athens (IG II2 3779) locates the games in Alexandria, but an inscription listing the victors in an iteration of the Basileia held in 267 BCE (SEG 27.1114) was found in the Fayum region, about 100 kilometers south of Alexandria. Therefore, it is often assumed that Basileia were held at several places in Egypt, with the main Basileia in Alexandria and local versions in the chora (e.g., Koenen 1977: 29–32; Nerwinski 1981: 118), but this is contrary to all other evidence for athletic contests and to logic. The field of potential competitors in Egypt was too small for multiple competitions to be feasible. For the games of 267, the inscription lists four victors from Macedonia, six from Thrace, one from Thessaly, one from Samos, one from Halicarnassos, one from Boeotia, one from Taras, and one from Naukratis. Since the victor list inscription is damaged, the names of another twenty victors (among them the artists) are missing. Some of the athletes can be identified with persons known from papyri, which shows that most, if not all, were living in Egypt and that they are identified in the victor list using their ethnika.4 The only known competitor from outside of Egypt was an Athenian artist (IG II2 3779). The inscribed victor list was found in the Fayum because it was erected by a local resident named Amadokos, whose three sons won victories in that iteration of the Basileia.5 Amadokos set up the inscription in his hometown to commemorate the achievements of his sons. The president of the contest is identified as an Alexandrian, which firmly locates the games in the capital.

One of the political subdivisions of the city of Alexandria, the deme of Eleusis, had a yearly festival with a musical and, possibly, athletic agon (P.Oxy. 26.2645 Fragment 3). A contest for artists was also held as part of the Dionysia festival in Alexandria (Theocritus Encomium to Ptolemy Philadelphus 112–4). The yearly feast of the Arsinoeia may have had an agonistic component as well (PSI 4.364).

Finally, there is the so-called Penteteris, which is often identified with the Ptolemaia. Athenaeus (196a–03b), using the work of Callixeinos of Rhodes as a source, supplies a detailed description of a procession in the reign of Ptolemy II. This procession was made up of 12 separate groupings, each of which was dedicated to a different god. Athenaeus only describes the Dionysian unit, but he mentions that the first unit was dedicated to Ptolemy I and Berenike and that the last was dedicated to Alexander. The procession belonged to a quadrennial festival with an agonistic component. Athenaeus does not name the festival, but notes that the information came from the records of the Penteterides. Therefore, the procession has been connected to four papyri dealing with supplies for a festival called Penteteris or Penteterikon, that is “the quadrennial feast,” which does not seem to be a proper name. The main arguments for identifying this Penteteris with the Ptolemaia are that the procession seems to have been designed to communicate a dynastic message and that the Ptolemaia is the best known quadrennial festival with an agonistic component. These arguments are inconclusive, however, as most Ptolemaic contests were parts of dynastic festivals and can be assumed to have been quadrennial or to have been held in a more splendid manner every four years. The identification of the festival described by Athenaeus with the Penteteris mentioned in papyri is also uncertain, as the records of the Penteterides – plural – may have contained information on all the penteteric festivals held in Alexandria. In order to make definitive statements as to the precise identity of the festival described by Athenaeus, we will have to wait for more evidence to come to light.

The aforementioned games were all held in Alexandria. Although most or all of them were instituted at the initiative of the king, Alexandrian citizens played prominent roles in organizing, presiding over, and running the contests. In the reign of Ptolemy III, the city of Ptolemais in Upper Egypt was granted the right to establish a contest for artists. In the metropoleis, however, there is no evidence for recurring contests with a full slate of events. This does not, however, mean a total absence of competitions. Local festivals connected to gymnasia could include some agonistic elements. For example, in the village of Psinachis in the Fayum, a region with many Greek immigrants serving in the Ptolemaic army, there was a contest for horsemen during a festival of Hermes (P.Genova 3.197).

Thus far, I have focused on competitive sport and neglected the other form of institutionalized sport, namely sport that took place in gymnasia. This type of sport involved a much broader segment of the Greek population of Egypt than the limited number of very talented athletes and very wealthy horse owners who took part in high-level competitions. Many immigrants wanted to institute gymnasia to recreate the facility that had served as training center and social club in their hometowns. They saw gymnasia as a place to meet their peers, to train their sons, and to cultivate a Greek way of life in what was for them, initially at least, a foreign land.

The absence of poleis in the Egyptian chora, which impeded the spread of agones, did not have the same dampening effect when it came to gymnasia. While the foundation of a successful new agon was a project that required interaction with a number of other communities, the construction of a gymnasion was a purely local concern, and private initiative could take the place of a formal decision. Gymnasia and palaistrai are attested in the Egyptian chora from the third century BCE on, even in villages.6 They were founded by members of the Greek elite, generally people from the circle around the king or military men. Their establishment helped foster the spread of sport in the chora. The ephebate (institutionalized physical training for youths) is not yet attested in the chora in the third and early second century BCE. Several papyri do mention neaniskoi, who were perhaps young officers above the age of ephebes, owning their own plots of land and training and socializing together in gymnasia (Habermann 2004).

As the Hellenistic period progressed, participation in the activities centered in gymnasia became part of a lifestyle that defined who belonged to the elite of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, for Greeks as well as Hellenized Egyptians. The use of ethnika referring to a Greek polis to express one’s Greek identity and privileged status was gradually abandoned. While for the first immigrants maintaining a sense of Greek ethnicity had been a major factor in the attraction of the gymnasion, this was now to a great extent replaced by the elite character of the institution. The gymnasia in the Egyptian villages and metropoleis started to conform to gymnasia in the rest of the Greek world. The first gymnasiarchs and evidence for the ephebate outside of Alexandria appear in the mid-second century BCE (SB 3.6159), but the organization of this early ephebate is not well known (Legras 1999: 133–42).

Under Roman rule, which began in 30 BCE, the elite in the chora evolved into what was called the gymnasial order (oi apo tou gymnasiou). This evolution confirms the importance of gymnasia as markers of an elite lifestyle. All 13-year-old boys aspiring to become ephebes had to demonstrate that their forefathers were gymnasion members in 4/5 CE. Originally, all freeborn sons of a father who was a member of the gymnasial order inherited this status, and the concomitant privileges, but in the third quarter of the first century CE the rules were tightened and, to be admitted to the gymnasial order, boys had to prove the gymnasial status of their maternal grandfather as well. Their applications for enrollment are well attested on papyrus (Legras 1999: 169–79; van Minnen 2002: 344–7). The main officials involved in the gymnasion administration – the gymnasiarch, the kosmetes, and the exegetes – were local magistrates, appointed by the Roman authorities from the local elite (Lewis 1983; Legras 1999: 181–7). In the administration of their gymnasia, the metropoleis therefore differed little from the more independent poleis, certainly by the second century CE.

Throughout the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods Alexandria remained the only place in Egypt with real agones. In the chora, local competitions for the young are attested from the second century BCE, for example torch races (BGU 4.1256), and athletes could also perform as a side event at various local festivals (e.g., P.Oxy. 3.519), but there is no evidence recurring contests with a full program of athletic events, competitors from outside the community, and prizes offered by an appointed agonothetes (contest organizer).

Even for the contests in the capital, there is little or no evidence for the second and first centuries BCE. It seems that when the third-century prosperity of the Ptolemies declined, some of the Alexandrian games disappeared. In the first and second centuries CE, when there was a notable increase of contests all across the eastern half of the Roman Empire (see Chapter 24), evidence for contests in Alexandria again appears in considerable quantities.

One contest held in Alexandria that appears for the first time during this period is the Seleukeios agon. This contest is attested in two inscriptions from the era of Roman rule, one not precisely dated and one from the early third century CE (Moretti 1953: no. 847), though it may have been founded as early as the Hellenistic period. The Seleukeios agon was presumably organized by the Alexandrian deme of that name, and is in that way similar to the Dionysia organized by the Alexandrian deme of Eleusis.8 In the middle of the first century CE, Tiberius Claudius Patrobios from Antioch won the pentaeterikos in Alexandria, as did two other athletes soon thereafter (Moretti 1953: nos. 65, 67, 68). This name has nothing to do with the Penteteris from the third century BCE. The adjective pentaeterikos occurs repeatedly in inscriptions, not only to describe the games in Alexandria, but also for games elsewhere. In the first and early second centuries CE, many cities had only one contest, usually without a famous name, so for champions it was not important to list the exact names of all contests; the name of the city said enough. Only in the middle of the second century, when several cities organized more than one contest, did it become common to mention all games by their proper name. Although it is impossible to be certain, the contest in which Tiberius Claudius Patrobios took part may have been the Seleukeios agon, as all other Alexandrian contests known by name from second or third-century inscriptions certainly did not yet exist at the time of Patrobios.

There is evidence from the first and second centuries CE for other contests at Alexandria, namely a biannual Sebasteios agon (Moretti 1953: no. 84) and annual ephebic games (P.Lond. 6.1912). In the reign of Hadrian (117–38 CE), the Hadrianeia was established, which was subsequently renamed the Hadrianeios Philadelpheios agon (Moretti 1953: no. 84). In 175/6, a festival called the Olympia was founded (Strasser 2004/5: 443).

As in the Ptolemaic period, not all these games were held in the city center. Just east of Alexandria, Octavian founded Nikopolis, a Roman military camp and small town with a stadium, theater, and racetrack for horses, where some of the Alexandrian agones took place (Strabo 17.1.10). In the city center, games took place in the stadium-hippodrome called the Lageion (e.g., SB 3.6220; cf. Remijsen 2010: 199).

When his favorite Antinoos drowned in the Nile in 130 CE, Hadrian founded a new polis at the spot, Antinoupolis. Upon its foundation, this city was granted the right to build a circus and to hold games, the Megala Antinoeia, that were sacred (in the technical sense of the term) (Decker 1973). The construction of a circus rather than a stadium was normal in regions with a limited tradition of stadia, such as Egypt or Syria (Humphrey 1986: 438–520). A circus could be used for both athletic and equestrian contests, and it had, moreover, more of the grandeur expected of an imperial donation. The Megala Antinoeia were annual, which was uncommon for agones with full programs, but typical of ephebic games (I.Portes 9; PSI 3.199). This shows that the competition for ephebes was the most important part of the games. Apparently a full program for adults and boys was added to the ephebic games, that is the Antinoeia proper, thus making them Megala.

With only four new contests (three in Alexandria and one in Antinoupolis), Egypt did not really participate in the general upsurge of contests in the eastern half of the Roman Empire in the first and second centuries CE, because most of its cities were still unable to found their own games. The athletes of Egypt, on the other hand, could profit from the international agonistic explosion. Alexandrians won a third of all Olympic stadion races in the first two centuries CE (i.e., in 16 out of 50 Olympiads). This overrepresentation of the city should be linked to the disappearance of ethnika (Remijsen 2009): all Egyptians now competed as Alexandrians. A good example is Marcus Aurelius Asklepiades, a well-known inhabitant of Hermopolis, who identified Alexandria as his hometown (IGUR 1.240).

When the emperor Septimius Severus granted the status of polis and the right to form city councils to the Egyptian metropoleis around 200 CE (Bowman 1971: 3–7, 11–19), gymnasion culture continued unchanged. Even after 212, when all free men in Egypt were given Roman citizenship, the gymnasial class continued to exist, as it represented a lifestyle that set the elite apart from the rest of the population. It was only in the fourth century that Egyptian gymnasia disappeared.

What did change in 200 was that the metropoleis could now finally take the initiative to establish games. Athletes from Egypt, moreover, were finally able to present themselves as citizens of their hometowns. By this time all areas in which Greek sport was practiced had long been incorporated into the Roman Empire, and, for the new Egyptian poleis, agones became a way to fit in within that great empire, as equals of the cities in other provinces, and to establish relations with those cities. Because it was necessary to apply to the emperor for permission to establish games or have them recognized as sacred, the introduction or reorganization of games was also a way to interact with the emperor and to express loyalty (e.g., Wörrle 1988: 4–17).

The first new Egyptian polis to have games was Hermopolis. This metropolis was located directly across the Nile River from Antinoupolis, which, as we have seen, had regularly held sacred games, the Megala Antinoeia, since its foundation in 130 CE. Officials of the local gymnasion had organized horse races shortly before polis status had been granted (P.Ryl. 2.86). Some of Hermopolis’s inhabitants, such as the aforementioned Marcus Aurelius Asklepiades, competed at the highest level athletic contests in the Greek world. Both he and his father were moreover presidents of the international athletic association, headquartered in Rome, which gave them considerable influence in the agonistic circuit. The people of Hermopolis were, therefore, in all probability eager to enter the agonistic circuit. It comes as no surprise then that before the death of Septimius Severus in 211, Hermopolis had succeeded in founding its own agon, called the Capitolia (IK Side 130).

In 200 the metropolis of Oxyrhynchus proposed to establish annual ephebic games, which were held for the first time in 210 and became sacred about ten years later (P.Oxy. 4.705; SB 10.10493). In 220 Leontopolis received sacred ephebic games as well (SEG 40.1568). Both contests were modeled after the Antinoeia and hence were called isantinoeios. It was uncommon that ephebic games were made sacred. This peculiarity can be explained by the precedent of the Megala Antinoeia, which were at the same time a sacred agon for professionals and games for ephebes. The isantinoeios contests were only for ephebes, but were granted sacred status just like their model.

A second wave of agones was founded by Egyptian metropoleis in the second half of the third century. Panopolis got the Paneia in 264 (P.Oxy. 27.2476; Van Rengen 1971; Strasser 2004/5: 465–8). Antinoupolis and Oxyrhynchus both got Capitolia, in 268 and 273, respectively (P.Oxy. 47.3367; BGU 4.1074). Lykopolis probably had games as well by this time, though their name is not known.9 The rapid succession of new foundations shows the competition between the cities. Each city wanted to do at least as well as the others.

By the late third century, the Egyptian contests formed a local circuit within the larger international scene. The catchment area of these games was relatively small; most competitors came from Egypt itself, as is apparent from a list of participants in the running contests of Hermopolis or Antinoupolis (P.Ryl. 2.93). The same impression is conveyed by third-century papyri that contain requests to the city council of Hermopolis for payment of pensions to victors (SPP 5.54–6, 69–70, 74); in these documents we meet a considerable number of competitors, but most of them were not international stars. The increase of local opportunities enabled local athletes to participate in contests in Egypt and nearby Syria.

There is still some evidence for the contests, athletic officials, and the ephebate in the early fourth century (e.g., P.Oxy. 1.42; 60.4079), but by the middle of the fourth century, the passion for sport seems to have declined noticeably in the chora. Contests may have survived until the end of the century only in Alexandria (Libanius Epistles 843, 1183; Isidorus Pelusiota Epistles 1470, 1651, 1671).

Throughout this essay I have made a distinction between competitive sport and gymnasion culture, which spread in different ways in Hellenistic Egypt. Agones, in the meaning of permanent, full-program contests with a regional or international catchment area, were always a status symbol, established as the result of a decision by a king or city wishing to manifest itself on the international scene. The first Ptolemies, Ptolemy II in particular, actively promoted competitive athletics. Alexandrian games with an unmistakable dynastic touch were founded one after the other, and competitors from Egypt, among them the royals themselves, achieved impressive results at the top games in Greece. Athletic contests did not spread beyond Alexandria, though, nor could other cities send out competitors in their own name. For five centuries, the specific organization of the metropoleis hindered the spread of sport in the chora.

When the royal investments dried up in the late third century BCE, Egypt’s place on the agonistic circuit became minimal for the rest of the Hellenistic period. In the first and second centuries CE, the general increase in the number of athletic contests, evident throughout the eastern half of the Roman Empire, was observable in Egypt as well, with new games in Alexandria and Antinoupolis. However, in comparison to Asia Minor or Syria, the administrative organization of the metropoleis still handicapped Egypt. All of this changed with the grant of polis status to the metropoleis in about 200 CE. In the third century CE, many of the new poleis established games and applied to the emperor for permission to make those games sacred. But it was not just because cities finally could establish games that they did this so eagerly. As in the Ptolemaic period, a contest was a status symbol, a way of showing the rest of the world that a city was just as important and autonomous as the other cities in the Empire.

Gymnasion culture spread in Egypt from the third century BCE on. In the beginning, its development was slower than that of the agones, as gymnasia were founded on private initiative and did not have a prominent role in the Ptolemaic policy. The royal sports policy was aimed more at presenting the kingdom to the outside world as Greek and powerful, than at stimulating the inhabitants to practice the Greek way of life. Egypt’s particular organization did not hinder the emerging gymnasion culture, however, although it explains why only in Egypt were there gymnasia in villages as well as towns. While the agones declined when royal involvement decreased, sport became deeply rooted in the lifestyle of the Ptolemaic elite through the gradual introduction of the ephebate in the second century BCE. The elite character of the gymnasion, one of its most alluring aspects, was responsible for its continuing popularity. Under the Romans, this characteristic was even formalized when membership of the gymnasion became the official criterion for belonging to the privileged upper class. The organization of the gymnasion, originally characterized by local particularities, gradually conformed to practices elsewhere. Gymnasia became civic institutions. In this way, they already prepared the elite in the metropoleis for their future role in the polis.

ABBREVIATIONS

All abbreviations of papyrus editions ( BGU, P.Genova , P.Lond., P.Oxy., PSI, P.Ryl., SB, SPP) are explained in the Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca and Tablets. See http://scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/papyrus/texts/clist.html.

Abbreviations of editions of inscriptions:

CID = Corpus des inscriptions de Delphes

FD 3 = Fouilles de Delphes III Épigraphie

IG II2 = Inscriptiones Graecae II et III (2nd edition)

IGUR = Inscriptiones graecae urbis Romae

IK Side = Side im Altertum. Geschichte und Zeugnisse

I.Portes = Les Portes du désert. Recueil des inscriptions grecques d’Antinooupolis, Tentyris, Koptos, Apollonopolis Parva et Apollonopolis Magna

IvO = Die Inschriften von Olympia

IvM = Die Inschriften von Magnesia am Maeander

PSI = Papiri greci e latini. Pubblicazioni della Società Italiana per la ricerca dei Papiri greci e latini in Egitto

SEG = Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum

Syll.3 = Sylloge inscriptionum graecarum (3rd edition)

NOTES

1 For a brief introduction to Posidippos’s hippika, see Golden 2008: 19–23. For more detailed considerations of the contents of the Posidippos papyrus, see the essays collected in Gutzwiller 2005, especially those by Fantuzzi (from whom I borrow the term “image of power”) and Thompson. For detailed discussion of what the Posidippos poems can tell us about sport in the Early Ptolemaic Kingdom, see Remijsen 2009. For instance, these poems, in conjunction with other source material, make it evident that members of the Ptolemaic court won 30 to 50 percent of the Olympic four-horse chariot races in the first half of the third century.

2 The identification of the Ptolemaia in Alexandria with the Ptolemaia in Hiera Nesos (previously regarded as a local contest in the Fayum), proposed in Remijsen 2009: 259 based on the location of another Hiera Nesos and a hippodrome just east of Alexandria, is now confirmed by the discovery of an extra piece of a letter of Ptolemy III to the city of Kos (SEG 53.855 l. 18–19).

3 On all of this terminology, see Remijsen 2011.

4 The victors listed in the inscription, and presumably most of the athletes competing at the Basileia, belonged to the upper strata of Ptolemaic society. The Thessalian Kineas, for example, was eponymous priest of Alexander in 263–2 BCE.

5 As Ebert (1979: 5–6) noted, Amadokos was not a contest organizer and had no official connection to the Basileia.

6 This stands in contrast to the situation in much of the rest of the Greek world, where gymnasia were strongly associated with urban centers. On the difference between gymnasia and palaistrai, see Chapter 19.

7 The other text is a fragmentary and still unpublished inscription from Delphi, cf. Robert 1948: 25.

8 The contest was not named directly after Seleukos (naming a contest after a rival king would be unique) but after the Alexandrian deme, which was named after Seleukos when he was still Ptolemy’s ally (Clarysse and Swinnen 1983: 14).

9 Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 27.2476 (288 CE) mentions two officials of the artistic association, an Alexandrian and a man from Antinoupolis, with citizenship of Lykopolis. Such multiple citizenships result from victories in local contests.

REFERENCES

Bennett, C. 2005. “Arsinoe and Berenice at the Olympics.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 154: 91–6.

Bonacasa, N., A. Di Vita, and G. Barone, eds. 1983. Alessandria e il mondo ellenistico-romano: Studi in onore di Achille Adriani. 3 vols. Rome.

Bonacasa, N., N. C. Naro, E. C. Portale, et al., eds. 1995. Alessandria e il mondo ellenistico-romano: I centenario del Museo greco-romano. Rome.

Bowman, A. 1971. The Town Councils of Roman Egypt. Toronto.

Clarysse, W. and W. Swinnen. 1983. “Notes on Some Alexandrian Demotics.” In N. Bonacasa, A. Di Vita, and G. Barone, eds. 1: 13–15.

Clarysse, W. and G. van der Veken. 1983. The Eponymous Priests of Ptolemaic Egypt. Leiden.

Criscuolo, L. 1995. “Alessandria e l’agonistica greca.” In N. Bonacasa, N. C. Naro, E. C. Portale, et al., eds., 43–8.

Decker, W. 1973. “Bemerkungen zum Agon für Antinoos in Antinoupolis (Antinoeia).” Kölner Beiträge zur Sportwissenschaft 2: 38–56.

Decker, W. 2006. Pharao und Sport. Mainz.

Decker, W. 2008. “Neue Olympiasieger aus Ägypten.” In W. Waitkus, ed., 67–81.

Ebert, J. 1979. “Zu Fackelläufen und anderen Problemen in einer griechischen agonistischen Inschrift aus Ägypten.” Stadion 5: 1–19.

Frisch, P. 1986. Zehn agonistische Papyri. Opladen.

Golden, M. 2008. Greek Sport and Social Status. Austin, TX.

Gutzwiller, K., ed. 2005. The New Posidippus: A Hellenistic Poetry Book. New York.

Habermann, W. 2004. “Gymnasien in Ptolemäischen Ägypten: Eine Skizze.” In D. Kah and P. Scholz, eds., 335–48.

Hölbl, G. 2001. A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. Translated by T. Saavedra. London.

Hornblower, S. and C. Morgan, eds. 2007. Pindar’s Poetry, Patrons, and Festivals: From Archaic Greece to the Roman Empire. Oxford.

Humphrey, J. H. 1986. Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. Berkeley.

Kah, D. and P. Scholz, eds. 2004. Das hellenistische Gymnasion. Berlin.

Koenen, L. 1977. Eine agonistische Inschrift aus Ägypten und frühptolemäische Königsfeste. Meisenheim.

La’da, C. 2002. Foreign Ethnics in Hellenistic Egypt. Leuven.

Legras, B. 1999. Néotês: Recherches sur les jeunes Grecs dans l’Egypte ptolémaïque et romaine. Geneva.

Lewis, N. 1983. “The Metropolitan Gymnasiarchy, Heritable and Salable.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik: 85–91.

Manning, J. G. 2010. The Last Pharaohs: Egypt under the Ptolemies, 305–30 BC. Princeton.

Melaerts, H. and L. Mooren, eds. 2002. Le rôle et le statut de la femme en Égypte hellénistique, romaine, et byzantine. Leuven.

Moretti, L. 1953. Iscrizioni agonistiche greche. Rome.

Nerwinski, L. A. 1981. “The Foundation Date of the Panhellenic Ptolemaea and Related Problems in Early Ptolemaic Chronology.” PhD diss., Duke University.

Nicholson, N. 2005. Aristocracy and Athletics in Archaic and Classical Greece. Cambridge.

Perpillou-Thomas, F. 1993. Fêtes d’Égypte ptolémaïque et romaine d’après la documentation papyrologique grecque. Leuven.

Perpillou-Thomas, F. 1995. “Artistes et athlètes dans les papyrus grecs d’Égypte.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 108: 225–51.

Remijsen, S. 2009. “Challenged by Egyptians: Greek Sports in the Third Century BC.” International Journal of the History of Sport 26: 246–71.

Remijsen, S. 2010. “Pammachon: A New Sport.” Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 47: 185–204.

Remijsen, S. 2011. “The So-Called ‘Crown Games’: Terminology and Historical Context of the Ancient Agones.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 177: 97–109.

Rice, E. E. 1983. The Grand Procession of Ptolemy Philadelphus. London.

Robert, L. 1948. “Dédicace votive.” Hellenica: Recueil d’épigraphie, de numismatique et d’antiquités grecques 6: 24–6.

Strasser, J.-Y. 2004/5. “Les Olympia d’Alexandrie et le pancratiaste M. Aur. Asklèpiades.” Bulletin de correspondance hellenique 128/9: 421–68.

van Bremen, R. 2007. “The Entire House is Full of Crowns: Hellenistic Agones and the Commemoration of Victory.” In S. Hornblower and C. Morgan, eds., 345–75.

van Minnen, P. 2002. “Ai apo gymnasiou: ‘Greek’ Women and the Greek ‘Elite’ in the Metropoleis of Roman Egypt.” In H. Melaerts and L. Mooren, eds., 337–53.

Van Rengen, W. 1971. “Les jeux de Panopolis.” Chronique d’Égypte 46: 136–41.

Waitkus, W., ed. 2008. Diener des Horus: Festschrift für Dieter Kurth zum 65. Geburtstag. Gladbeck.

Wörrle, M. 1988. Stadt und Fest im kaiserzeitlichen Kleinasien. Munich.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

On sport in Egypt before Alexander’s conquest, see Decker 2006. For relatively brief overviews of the history of the Ptolemaic period in Egypt see Hölbl 2001 or Manning 2010.

Perpillou-Thomas collected the evidence for festivals in Greco-Roman Egypt (1993) and listed all artists and athletes known from Greek-language papyri (1995). Together with Criscuolo’s brief discussion of the Alexandrian contests (1995), these works offer a good starting point for sport in Egypt.

For the Ptolemaic period, more detailed studies have mostly focused on the Ptolemaia and in particular on its possible identification with the procession described by Callixeinos (e.g., Nerwinski 1981; Rice 1983), on Egyptian participation in the major Panhellenic athletic festivals (e.g., Bennett 2005 and Decker 2008), and more recently on the epigrams of Posidippos (e.g., van Bremen 2007 and Remijsen 2009).

Kah and Scholz 2004 is a recent collection of essays on the Hellenistic gymnasion. On the ephebate in Egypt, see Legras 1999.

For the Roman period, the most interesting papyri have been collected in Frisch 1986. The best discussion of the contests in the Egyptian chora is Strasser 2004/5. The forthcoming volume of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri (P.Oxy. 79) will publish several new papyri on Imperial age games in Egypt.