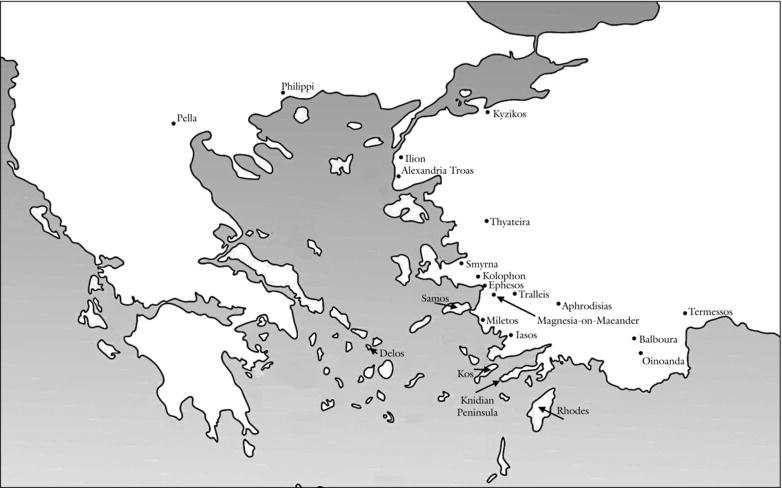

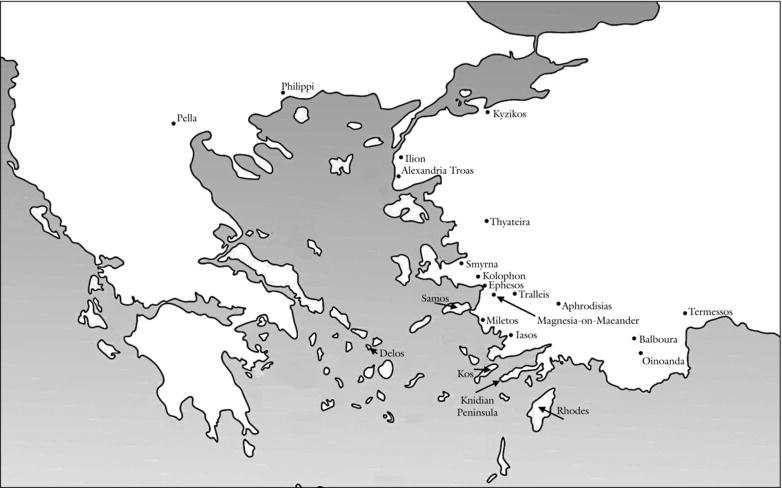

Map 24.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

While the study of Greek sport traditionally concentrates on mainland Greece in the Archaic (700–480 BCE)1 and Classical (480–323) periods, this Companion shows that the sporting world of the Greeks was much broader in both geographical and chronological scope (e.g., see essays on the Greek West, Chapter 13; Hellenistic Egypt, Chapter 23; and Constantinople, Chapter 43; see also Scanlon 2009). This essay surveys the contribution of communities in Asia Minor (defined roughly as the territory of present day Turkey) to the spread and longevity of Greek sport in the Hellenistic (323–31) and Roman (31 BCE–476 CE) periods by focusing on three themes.

First, we will explore the remarkable growth of the “agonistic market” (the totality of athletic contests held in any given period). The evidence pertaining to Greek sport in Asia Minor prior to the fourth century is meager and often incidental. In the course of the Hellenistic period, Greek civilization, urbanization, and sport steadily expanded eastward from the coastal areas to the rest of Asia Minor, and this process continued and in some ways intensified during the early centuries of Roman rule. There is a concomitant increase in the number of extant documents, most notably inscriptions, concerning athletes, festivals, and facilities. Those documents, when carefully collected and properly analyzed, make it possible to study sport in Hellenistic and Roman Asia Minor in considerable detail.2 Conspicuous among the concerns of cities in Asia Minor, both those inhabited largely by Greeks and those inhabited by non-Greeks who were adopting some elements of Greek culture (i.e., Hellenizing), was the foundation of athletic contests. There was, as a result, an ongoing expansion of the agonistic market in Asia Minor between the fourth century BCE and the third century CE.

The sports activity that took place in the cities in Asia Minor went far beyond athletic contests and included the construction and maintenance of a “sports culture” that encouraged regular training in local gymnasia and valorized athletic success at all levels of competition. What this sports culture meant for cities and for the relationship between urban elites, civic life, and identity on the one hand and sport on the other is the second theme of this essay.

As long as they paid taxes and maintained law and order, the cities of Asia Minor were largely allowed to manage their own athletic matters during both the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Urban autonomy in agonistic matters, however, did not mean that Roman emperors and their representatives in the provinces played no role in the development of agonistic life. Our third theme, then, is the role of Roman emperors in the operation of Greek sport. The generally attentive and positive involvement of Roman emperors in athletic festivals and rewards for victors may come as a surprise to some readers.

The story of sport in Asia Minor stretches back long before the beginning of the Hellenistic period, but we are largely ignorant about athletic activities in Greek communities in Asia Minor in the Archaic and Classical periods. In the lists of Olympic victors, athletes from Asia Minor are rare until well into the fourth century.

An isolated anecdote related by Herodotus (1.144) about a certain Agasikles from Halicarnassos is amusing but not very helpful. At some point in the Archaic period, a festival was celebrated on the Knidian peninsula in southwestern Asia Minor (see Map 24.1 for the locations of key sites mentioned in this essay) in honor of Apollo. Victors received bronze tripods, which they were supposed to dedicate in the temple. When a certain Agasikles was greedy and took his tripod back home, his city was punished for it. The story recalls other contemporary contests in mainland Greece, with bronze tripods or cauldrons as prizes for the winners. In the case of Agasikles we probably have a local contest. We have no idea whatsoever how many such contests existed in Archaic Asia Minor.

The extant evidence points to an upward shift in athletic activity in Asia Minor in the latter decades of the fourth century. It is not until the later fourth century that honorary decrees from Asia Minor make mention of the privilege of proedria (special seating at public events) at “all the contests celebrated in the city.” The wording of these decrees, attested first at Ilion and Iasos, points to the existence of contests, including athletic contests, of some importance in these communities. A decree of c.300 from Ilion records that an honorand received proedria at a festival, the Panathenaia, celebrated there (Frisch 1975: nos. 1, 24; SEG 53.1373; Knoepfler 2010). An inscription of roughly the same date from Ephesos shows that a young athlete had crossed the Aegean and won as a boy in the Nemean Games (Robert 1969–90: vol. 5: 354–72; Brunet 2003). This implies that he had already been successful in the local gymnasion and in lesser contests organized in the city or region. Similarly it is in the fourth century that athletes from Asia Minor appear in the list of Olympic victors, albeit in relatively small numbers.

Map 24.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

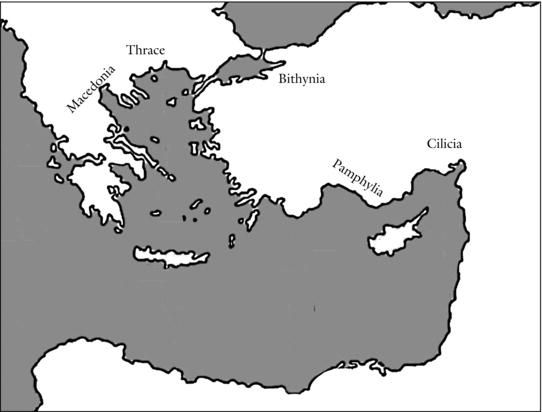

Map 24.2 Key regions mentioned in this essay.

In the third century, cities in Asia Minor apparently wanted to compete with the great games of mainland Greece. Kos, an independent polis (city-state) in the Hellenistic period, but in the Roman period part of the province of Asia, set the trend. In 242/1 the city decided to dispatch theoroi (ambassadors) all over the Greek world (from Naples in southern Italy to the regions of Thrace and Macedonia in northern Greece, see Map 24.2) requesting dozens of cities (and a few monarchs) to recognize their local, preexisting athletic contest held as part of the Asklepieia festival as a “stephanitic agon” (crown game). In the Archaic and Classical periods, Greeks used the phrase “stephanitic agon” to refer to athletic contests that awarded only wreaths as prizes, which in practice meant primarily the Olympic, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games. Starting in the third century this terminology was used to refer to any set of athletic contests organized such that victors received much the same privileges as victors in the original crown games.3 In order to become a stephanitic agon, a contest’s organizers had to ask that other communities add it to the list of such games recognized by the community in question. Within the broad category of crown games, cities could decide to give isolympic (“equal to the Olympic Games”) or isopythian (“equal to the Pythian Games”) status to them. This entailed special, and probably higher, rewards for the victors. The privileges possibly consisted of free meals in the town hall, an honorary position in processions, and special portions of meat during sacrifices (see Chapter 23 for further discussion).

The Koan theoroi seem to have asked the inhabitants of other cities to join in the sacrifices and contests at the Koan Asklepieia and to keep to a truce during the festival.4 They did not officially ask for recognition of their local athletic contest as a stephanitic agon, but from the answers of three cities (Philippi, Pella, and Gela) we may infer that the Koan request was, at least by those three, interpreted as such. The gifts that the cities decided to give to the Koan theoroi were to be the same as those given to the theoroi who announced “the stephanitic games, the Pythian or Olympic Games” (IG XII 4 220–1, 223).5

The citizens of Magnesia-on-Maeander followed suit. In 222/1 they proposed to raise the status of the athletic contest held as part of the Leukophryena (a festival celebrated at Magnesia in honor of Artemis Leukophryene) to that of a crown game. The overture was rebuffed, but in 208 they tried again. They sent ambassadors “to the kings and the other Greeks,” many of whom agreed to recognize the Leukophryena not only as a crown game, but also as an isopythian contest.6

In roughly the same period (218/7–206/5) the inhabitants of Miletos sent out theoroi with a request to “kings, cities, and tribes [ethne]” to recognize their Didymeia, celebrated in honor of their patron deity Apollo Didymaios, as a crown game, and to award the highest possible privileges [timai] to the winners (IG XII 4 153; Thonemann 2007).

In the third and second centuries athletic contests proliferated in Asia Minor. Louis and Jeanne Robert list 13 separate crown games spread between Asia Minor and on two islands, Samos and Kos, off the coast (Robert and Robert 1989: 20; cf. Parker 2004). An honorary decree from Kolophon dated to c.180–160 records the gift of portions of sacrificial meat to “those who have won in crown games” (SEG 56.1227, ll. 24–5). In a somewhat later decree from the same city a young athlete is praised for having been victorious at crown games (SEG 39.1243, col. I; cf. 1244, col. I app. cr. ad l. 1). After the end of his athletic career, this athlete was sent as theoros to Smyrna and “joined in the traditional sacrifices together with a colleague theoros.” In other words, Kolophon had recognized a contest at Smyrna as a crown game. Sometime in the second century the citizens of Kyzikos sought to raise the status of their local Soteria, celebrated in honor of the goddess Kore, to that of a crown game and sent out theoroi to that end. Delos and Rhodes are known to have reacted positively, and it is a reasonable assumption that other cities did the same (Robert 1987: 156–62). It is also noteworthy that from the third century onward a substantial fraction of Olympic victors came from communities in Asia Minor (van Nijf 1999: 177–9).

Coins and inscriptions reveal that an astounding number of athletic contests were held in an increasingly urbanized Asia Minor during the first three centuries CE. In an often-quoted expression, Robert writes about “an athletic explosion” (1969–90: vol. 6: 712; also in König 2010: 111). Contests were established by newly founded cities and by settlements that achieved the legal status of polis thanks to population growth and economic prosperity. Emperor cult was also responsible for the dissemination of games. Leagues (koina) formed by communities in the various Roman provinces in Asia Minor founded or renamed festivals to honor emperors and in doing so created new athletic contests (Mitchell 1993: vol. 1: 219). Festivals called Kaisareia, Augousteia, Sebasta, Tiberieia, Claudieia, Vespasianeia, Traianeia, and Hadrianeia sprang up at various places in Asia Minor in the first and second centuries CE (Robert 1969–90: vol. 6: 712). Not all emperors favored the foundation of new festivals or the renaming of existing ones in their honor. Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius are not known to have given their names to contests. Under Commodus and the Severans, however, we find a throng of contests called Kommodeia, Severeia, and Anton(in)eia. In the third century CE games were often founded in regions regularly visited by imperial armies on their way to the eastern front, such as Bithynia, Cilicia, and Pamphylia (see Map 24.2). Such new games were sometimes a reward for the cities’ logistical support (Mitchell 1990: 192). On the basis of epigraphic and numismatic evidence, Wolfgang Leschhorn has concluded that during the zenith of Roman imperial rule in Asia Minor 350–400 contests are on record (Leschhorn 1998).7

Most of the hundreds of athletic contests in Asia Minor were not high profile crown games but money games of purely local significance. Victors at money games received valuable prizes such as cash from the contest’s organizers but were not typically eligible for special rewards granted by their hometowns. These contests, called themides, were often quadrennial, occasionally annual. The majority of the competitors at themides were hometown “stars” and athletes from neighboring communities (Pleket 1998a). However, talented athletes who competed at high-level contests such as the Olympics and crown games held in Asia Minor did not neglect money games. Inscribed victory catalogs, carved, among other places, into the stone bases of honorary statues for successful athletes, mention in great detail victories in dozens of well-known contests and frequently dryly conclude with a clause like, “and he won also in so-and-so many money games.” We can infer, based on numerous extant lists of prizes given for specific events at various contests, that the heavy events (boxing, wrestling, pankration) were much more popular than running and the pentathlon (Roueché 1993: 167–73).

Local athletic contests were financed from the public budget of the host city, from contributions by local magistrates presiding over the games (agonothetai, singular agonothetes), and from the revenues of endowments earmarked for the celebration of a contest in honor of the deceased donor – often a wealthy member of the city elite – or a local deity. Spectators were never charged in antiquity.

For various cities in Asia Minor, small dossiers of relevant sources have been collected and analyzed. Some dossiers allow a glimpse into the fundamental importance of sport in education and in public life in general. For the city of Termessos (located in the region of Pisidia, in south-central Anatolia), we are fortunate to have lists of names of athletic victors in games held at the two local gymnasia. The gymnasion, which constituted what I have termed elsewhere the “infrastructure of Greek athletics” (Pleket 1998a: 153–4), was the training ground for athletes, who competed first in local contests held at gymnasia and as part of urban festivals and subsequently, if they had sufficient talent and ambition, in higher level games. The epigraphic evidence records at least fifteen different athletic contests in Termessos. Most were celebrated in honor of deceased wealthy citizens, who in this way immortalized themselves; others were dedicated to a local deity. Lists of victors in gymnasion games were inscribed on the walls of public buildings. Honorific inscriptions erected for victors in local Termessian games were set up at prestigious locations in the city, not hidden in out-of-the-way places. In Onno van Nijf’s words, “the image of athletic victory could totally dominate [the] urban landscape” (1999: 191; cf. van Nijf 2000 and 2011).

Although quantitatively much less impressive, similar dossiers have been assembled for the cities of Oinoanda and Balboura in Lykia in south-central Anatolia (Strasser 2001: 118–24; Farrington 2008). Oinoanda organized at least five festivals that included athletic contests, all founded and financed by wealthy citizens: the Antipatrianeia, Demostheneia, Euaresteia, Meleagreia, and a fifth for which the name probably was derived from the names of the couple who financed it (SEG 44.1165–1201). That all these festivals were open only to Lykians is confirmed by the fact that all known winners are from Lykian cities (Pleket 1998b: 129–30).

Several facts point to the immense popularity of sport in such cities. Oinoanda’s Demostheneia started in 124–6 CE as a musical and cultural contest. The majority of the revenues from an endowment left by G. Iulius Demosthenes was spent on prize money for poets, musicians, and rhetors, while only 3 percent of the available money was earmarked for prizes in athletic contests, in which only citizens of Oinoanda could participate (Wörrle 1988; SEG 38.1462; for an English translation and discussion of the Greek inscription, see Mitchell 1990). Much later, a wealthy citizen turned this minievent into an official Pan-Lykian athletic contest, and we have two honorary inscriptions for wrestlers, but none for artists.

Oinoanda’s Euaresteia were founded by a “professor of literature,” Iulius Euarestos, whose brother-in-law was both a poet and a victorious wrestler and pankratiast (SEG 44.1165 and 1182). Euarestos, a man of culture, nevertheless established an athletic contest. After the fifth celebration he decided to add a musical contest, but the 18 honorary inscriptions found in Oinoanda and related to the Euaresteia exclusively concern athletic victors; artists are entirely absent. In spite of the cultural preferences of individual gentlemen – and of emperors like Hadrian, who approved Euarestos’s initiative – sport prevailed over culture or was at least equal to it.

In the city of Balboura we have, once again, a festival called the Meleagreia, probably founded by the same Meleagros who was responsible for the contest of that name in Oinoanda (SEG 38.1446–8 and 1459; SEG 41.1343–54). The festival had a musical component and an athletic component, but the inscriptions we have are all in honor of athletic champions.

Athletic performances were a cardinal element in expressing the self-identity of urban elites in Asia Minor (Pleket 2001: 205; van Nijf 1999: 189–90). The texts from Balboura predominantly record winners (boys and men) from the civic elite. Four inscriptions from Oinoanda (SEG 44.1169, 1194–6) concern L. Septimius Flavianus Flavillianus, an eminent member of a very wealthy family. He started his athletic career in wrestling and pankration as a boy in the local Meleagreia, subsequently excelled at high-level contests in numerous other places in the Greek world, and ultimately returned to Oinoanda to win as an adult in the Meleagreia and Euaresteia (Pleket 1998b: 130–1; van Nijf 1999: 189–90). His family was exceedingly proud of his performance. A family member, Licinnia Flavilla, erected a long genealogical inscription that lists numerous family members who had served as presidents of the Lykian League, Roman senators, and even consuls. When it comes to Flavillianus, she suddenly adds a brief sentence: “He was a specialist in the pankration and had won in sacred contests” (van Nijf 2001: 322).

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, Roman emperors and their governors allowed the cities of Asia Minor a reasonable degree of freedom to organize civic life as they saw fit. Roman authorities were interested primarily in law and order, safe roads through Asia Minor toward the “eastern front,” and timely payment of taxes. Since urban elites were ultimately responsible for the levying of taxes, Roman authorities automatically had a stake in sound financial budgets in the cities. If elites invested too much money in overly risky projects, the obligation to stand surety for the payment of the imposed taxes might not be met.

Emperors entered the playing field when cities created a new crown contest. Louis Robert is of the opinion that every new crown contest was in fact a dorea (donatio), a “gift” of the emperor. Permission was wrapped up in the much nicer ideological garment of a gift. That the gift normally implied financial support from the emperor is improbable (Robert 1969–90: vol. 6: 111; Mitchell 1990: 191). There is some evidence to show that cities continued the Hellenistic tradition of sending out theoroi proclaiming the new contest and asking for recognition (Robert 1987: 165–6; 1969–90: vol. 7: 754, 761, 779). When Ephesos created a new crown contest that was linked to the construction of a new temple for the emperor cult, more than thirteen cities sent theoroi to attend the contest and “join in the sacrifices” (Weiss 1998: 59). This implies that prior to this Ephesos itself had sent out theoroi to announce the festival.

Why would emperors insist on giving permission for such an operation? First, emperors realized that the creation of a new contest was an important expression of the self-identity of the Greek city. Sport was a fundamental part of Greek identity, and the foundation of an athletic contest in honor of the emperor was a way to stay Greek while simultaneously declaring and strengthening loyalty to the Roman state. There was, however, also a more pragmatic consideration: money and city budgets. Victors in crown games were lavishly rewarded by their home cities. Hellenistic-era inscriptions from Miletos and Tralleis show that hieronikai (victors in crown games) received cash from their mother cities (Robert 1969–90: vol. 1: 11–20; Slater 2010: 268–72). Though exact amounts of money are never mentioned, it is beyond doubt that internationally successful athletes presented a substantial burden to cities. Emperors may have wanted to control at least the part of the urban budgets devoted to sport.

Within the general category of crown games, a special category came into existence: the so-called eiselastic games. A victor in an eiselastic game received special amounts of money after he had “entered” (eiselaunein) his home city. It is an attractive hypothesis that eiselastic awards replaced the so-called siteresia (payments in cash) on record for the Hellenistic period. More research is necessary on this point, especially on the problem of the nature of these allowances, often but perhaps misleadingly denoted by modern scholars as “lifelong pensions” (Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 56.1359 apparatus criticus; Slater 2010: 268–72). Egyptian papyri show that substantial amounts of money were at stake and seem to suggest that the awards were paid as lump sums.

Apparently the eiselastic awards were important enough for athletes to address the emperor about the method of calculating the sums involved (Pliny Epistles 10.118–19; SEG 56.1359, ll. 10, 19, 25–6, 46, and 49–51). In a recently found letter from Alexandria Troas in northwestern Asia Minor, the emperor Hadrian (ruled 117–38 CE) altered Trajan’s earlier decision that the allowances should be payable from the moment of “eiselastic” entry, not from the moment of victory. Hadrian pleased the athletes with his decision that the rewards were to be due “not from the day on which someone entered his home city, but from the day the letter about the victory was delivered to their home cities. Those hurrying on to other contests were also allowed to send the letter” (Petzl and Schwertheim 2006: ll. 49–51). (For an English translation of this and two other letters on similar subjects, all written by Hadrian, see Jones 2007.)

Special permission from the emperor was necessary for transforming a crown game into an eiselastic contest. In the early third century CE the city of Thyateira in western Asia Minor sent the pankratiast and Olympic victor G. Perelius Aurelius Alexander to Rome to ask a favor from Caracalla, namely that the emperor allow a rise in status for the preexisting Augousteia to the rank of a “sacred eiselastic isopythios” contest (Robert 1937: 119–23). Forty years earlier Marcus Aurelius and Commodus gave the people of Miletos permission to raise their crown contest, the Didymeia, to the status of an eiselastic contest (SEG 38.1212). It is hard to imagine that emperors really cared about such technical niceties were it not for the serious budgetary consequences for the athletes’ home cities. Indeed, in their letters on this subject, emperors seem concerned about the financial burden of such contests (Mitchell 1990: 190).

Imperial consent was not required to found themides, which did not entail heavy financial burdens, but cities were nonetheless in the habit of asking emperors for permission and authorization. In the case of the aforementioned Demostheneia in Oinoanda, the assembly asked the emperor to confirm the founder’s promise to finance the contest. Hadrian did so, but he emphatically added: “He [the founder] will pay all expenses out of his own capital.” Somewhat later the provincial governor was asked to confirm the decision of the assembly to introduce tax-free status for all items sold during the days of the festival. The governor agreed under the strict condition that “the city’s revenues are in no way diminished.” Clearly concerns about urban budgets were uppermost in the minds of authorities (Wörrle 1988: 172–82).

Why did cities voluntarily ask for imperial approval? The answer perhaps lies in the beginning of Hadrian’s first letter from Alexandria Troas (see Chapter 6): sometimes magistrates could not be trusted (SEG 56.1359, ll. 8–13). They diverted money earmarked for contests and prizes to other purposes. No matter how essential sport and success were for the city’s image, there were always people who preferred investments in buildings or the purchase of grain.

Many athletic festivals, and accordingly many athletic victors, are known from the evidence for the history of sport in Asia Minor, which adds a great deal to the broader picture of the phenomenon of Greek sport throughout the ancient Mediterranean. Inscriptions and coins provide insights into the development of a large agonistic market, important elements of the sports culture, and the role of games in relations and communications between cities and the imperial administration.

Greek games in Asia Minor thrived and continued well into Late Antiquity (e.g., at Aphrodisias, see Roueché 1993), but eventually the combination of dwindling resources, political and military instability, and Christian antipathy ended that long and illustrious tradition of sport (Roueché 2007).8

ABBREVIATIONS

IG = Inscriptiones Graecae

SEG = Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum

NOTES

1 All dates are BCE unless otherwise indicated.

2 For more discussion of the evidence and an even broader contextualization of Greek sport in Hellenistic and Roman times, see Chapter 6, where I discuss inscriptions as material evidence.

3 Some of the games that eventually came under the heading of crown games in fact awarded both crowns and valuable material prizes.

4 Keeping a truce meant allowing safe passage to athletes and spectators traveling to and from the festival.

5 On Hellenistic Kos and its attempt to elevate the status of its local athletic contest, see the articles collected in Höghammar 2004. For a different view see Slater 2012.

6 On the games at Magnesia-on-Maeander, see SEG 56.1231; Slater and Summa 2006; Sosin 2009; Sumi 2004; and Thonemann 2007.

7 Leschorn 1998 found records for some five hundred games in all with the inclusion of Macedonia, Thrace, and continental Greece.

8 On the persistence of chariot racing in the Byzantine Empire, see Chapter 43.

REFERENCES

Bell, S. and G. Davies. 2004. Games and Festivals in Classical Antiquity: Proceedings of the Conference held in Edinburgh 10–12 July 2000. Oxford.

Brunet, S. 2003. “Olympic Hopefuls from Ephesos.” Journal of Sport History 30: 219–35.

Brunet, S. 2011. “Living in the Shadow of the Past: Greek Athletes during the Roman Empire.” In B. Goff and M. Simpson, eds., 90–108.

Cooley, A., ed. 2000. The Afterlife of Inscriptions: Reusing, Rediscovering, Reinventing, and Revitalizing Ancient Inscriptions. London.

Dietl, B. Forthcoming. Agonistische Inschriften aus Pisidien. Bonn.

Farrington, A. 2008. “Themides and the Local Elites of Lycia, Pamphylia, and Pisidia.” In A. D. Rizakis and F. Camia, eds., 241–9.

Frisch, P. 1975. Die Inschriften von Ilion. Bonn.

Goff, B. and M. Simpson, eds. 2011. Thinking the Olympics: The Classical Tradition and the Modern Games. London.

Goldhill, S., ed. 2001. Being Greek under Rome: Cultural Identity, the Second Sophistic and the Development of Empire. Cambridge.

Höghammar, K., ed. 2004. The Hellenistic Polis of Kos: State, Economy, and Culture. Uppsala.

Jones, C. 2007. “Three New Letters of the Emperor Hadrian.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 161: 145–56.

Knoepfler, D. 2010. “Les agonothètes de la Confédération d’Athéna Ilias. Une interprétation nouvelle des données épigraphiques et ses conséquences pour la chronologie des émissions monétaires du Koinon.” Studi Ellenistici 24: 33–62.

König, J. 2005. Athletics and Literature in the Roman Empire. Cambridge.

König, J, ed. 2010. Greek Athletics. Edinburgh.

Le Guen, B., ed. 2010. L’argent dans les concours du monde grec. Saint-Denis.

Leschhorn, W. 1998. “Die Verbreitung von Agonen in den Östlichen Provinzen des Römischen Reiches.” Stadion 24: 31–57.

Mitchell, S. 1990. “Festivals, Games, and Civic Life in Roman Asia Minor.” Journal of Roman Studies 80: 183–93.

Mitchell, S. 1993. Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor. 2 vols. Oxford.

Parker, R. 2004. “New ‘Panhellenic’ Festivals in Hellenistic Greece.” In R. Schlesier and U. Zellmann, eds., 9–22.

Pleket, H. W. 1998a. “Mass-Sport and Local Infrastructure in the Greek Cities of Roman Asia Minor.” Stadion 24: 151–72.

Pleket, H. W. 1998b. “Varia Agonistica.” Epigraphica Anatolica: Zeitschrift für Epigraphik und historische Geographie Anatoliens 30: 129–32.

Pleket, H. W. 2001. “Zur Soziologie des antiken Sports.” Nikephoros 14: 157–212.

Rizakis, A. D. and F. Camia, eds. 2008. Pathways to Power: Civic Elites in the Eastern Part of the Roman Empire. Athens.

Robert, L. 1937. Études anatoliennes: Recherches sur les inscriptions grecques de l’Asie Mineure. Paris.

Robert, L. 1948a. “Hierokaisareia.” Hellenica: Recueil d’épigraphie, de numismatique et d’antiquités grecques 6: 72–9.

Robert, L. 1948b. “Thyatira.” Hellenica: Recueil d’épigraphie, de numismatique et d’antiquités grecques 6: 43–8.

Robert, L. 1969–90. Opera Minora Selecta: Epigraphie et antiquité grecques. 7 vols. Amsterdam.

Robert, L. 1987. Documents d’Asie Mineure. Paris.

Robert, L. and J. Robert. 1989. Claros I: Décrets hellénistiques. Paris.

Roueché, C. 1993. Performers and Partisans at Aphrodisias in the Roman and Late Roman Periods. London.

Roueché, C. 2007. “Spectacles in Late Antiquity: Some Observations.” Antiquité Tardive 15: 59–64.

Scanlon, T. 2009. “Contesting Ancient Mediterranean Sport.” International Journal of the History of Sport 26: 149–60.

Scanlon, T. Forthcoming. Oxford Readings in Greek and Roman Sport. Oxford.

Schlesier, R. and U. Zellmann, eds. 2004. Mobility and Travel in the Mediterranean from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Munich.

Slater, W. 2010. “Paying the Pipers.” In B. Le Guen, ed., 249–81.

Slater, W. 2012. “Stephanitic Orthodoxy?” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 182: 168–78.

Slater, W. and D. Summa. 2006. “Crowns at Magnesia.” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 46: 275–99.

Sosin, J. 2009. “Magnesian Inviolability.” Transactions of the American Philological Association 139: 369–410.

Strasser, J.-Y. 2001. “Études sur les concours d’Occident.” Nikephoros 14: 109–55.

Sumi, G. 2004. “Civic Self-Representation in the Hellenistic World: The Festival of Artemis Leukophryene in Magnesia-on-the-Maeander.” In S. Bell and G. Davies, eds., 79–92.

Thonemann, P. 2007. “Magnesia and the Greeks of Asia (I. Magnesia 16.16).” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 47: 151–60.

van Nijf, O. 1999. “Athletics, Festivals and Greek Identity in the Roman East.” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 45: 176–200.

van Nijf, O. 2000. “Inscriptions and Civic Memory in the Roman East.” In A. Cooley, ed., 21–36.

van Nijf, O. 2001. “Local Heroes: Athletics, Festivals, and Elite Self-Fashioning in the Roman East.” In S. Goldhill, ed., 306–34.

van Nijf, O. 2011. “Public Space and Political Culture in Roman Termessos.” In O. van Nijf and R. Alston, eds., 215–42.

van Nijf, O. and R. Alston, eds. 2011. Political Culture in the Greek City after the Classical Age. Leuven.

Weiss, P. 1998. “Festgesandtschaften, städtisches Prestige, und Homonoiaprägungen.” Stadion 24: 59–70.

Wörrle, M. 1988. Stadt und Fest im kaiserzeitlichen Kleinasien. Munich.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

No one monograph offers a synthetic view of sport in Asia Minor. Mitchell 1990 and 1993: vol. 1: 217–26 offer brief but excellent surveys on games in Asia Minor in general. Robert’s numerous, and important, articles on this subject are easily accessible in his Opera Minora Selecta. König 2010, chapters 4, 5, 7, and 8 republishes four relevant and important articles. The same applies to chapters in Scanlon (forthcoming). Relevant articles also often appear in the journal Nikephoros. Brunet 2003 and Roueché 1993 discuss sport in the cities of Ephesos and Aphrodisias. Much has been written about sport in Magnesia-on-Maeander; the relevant scholarship includes Slater and Summa 2006; Sosin 2009; Sumi 2004; and Thonemann 2007. On sport in Oinoanda, see Wörrle 1988.

For many cities in Asia Minor we now have corpora of inscriptions, with special sections on agonistic texts; see the series of Inschriften griechischer Städte aus Kleinasien. Dietl forthcoming is devoted entirely to agonistic inscriptions from Pisidia in southern Turkey. For Hierokaisareia and Thyateira in Lydia, see Robert 1948a and b. Agonistic inscriptions regularly appear in Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum.

On the growth of the agonistic market in Asia Minor, particularly during the Roman era, see Leschhorn 1998. König (2005), using both literary texts and inscriptions, shows that eastern Greeks were concerned about contemporary games, about their relationship to their Greek past, and about their present situation under Roman rule. On that same subject also see Brunet 2011. On the importance of sport to local elites in Asia Minor in the first through third centuries CE, see van Nijf 1999, 2000, and 2001.