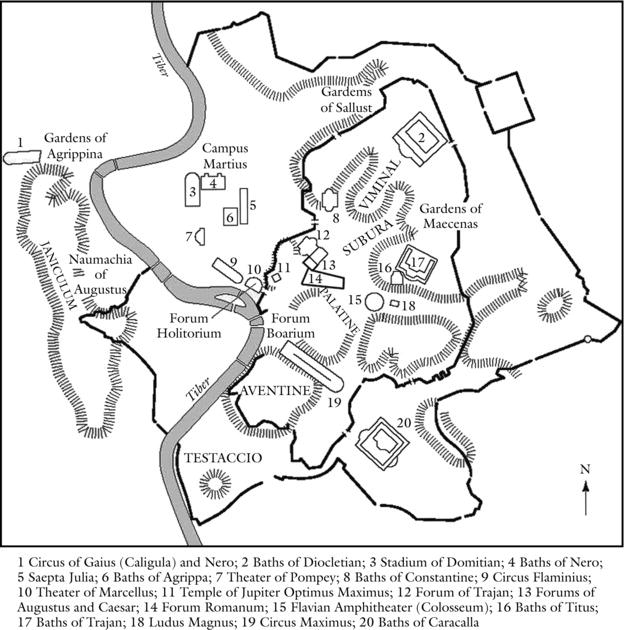

Map 25.1 Plan of ancient Rome showing major spectacle sites.

The story of the public entertainment the Romans called a spectacle (spectaculum, something worth seeing) begins in religious concerns. In its earliest years the primary purpose of the spectacle was to win the good will of the gods, especially in times of crisis, by providing them with good entertainment. This is not to say, however, that the human audience was not taken into consideration. The attraction that spectacles held for the Romans is evident from the steady and abundant proliferation of religious festivals requiring shows made possible by a professionalized entertainment industry.

What did the Romans (and presumably the gods) consider most worth seeing? The answer is clear: an assortment of physical contests and various kinds of dramatic presentation. The most popular spectacles included chariot races (ludi circenses), drama (ludi scaenici), gladiatorial combats (munus), staged animal hunts (venatio), staged naval battles (naumachia), and Greek athletic contests featuring Greek athletes (athletae). Although the triumphal celebration given by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE to commemorate his victory in the civil wars managed to accommodate all these events in one grand festival (Suetonius Julius Caesar 37–9), such spectacles were usually given alone or in various more limited combinations. This essay will review these spectacles in turn, going through them in chronological order based on their first appearance at Rome.

Ludi seem to have originated in a vow to a divinity made by a magistrate to present games on the state’s behalf, or by a general in return for victory. Once instituted, these games frequently became annual events. Ludi were viewed as an effective way of winning the favor of the gods and formed part of the religious calendar from the early years of the Roman Republic (c.509–31 BCE) and perhaps even earlier.

The most famous ludi were promised to Jupiter Optimus Maximus as an extra inducement beyond the usual sacrifices. Starting sometime around 366 BCE these games, which became known as the ludi Romani, were held annually in September (Balsdon 1969: 245). The main events of the festival were several days of chariot races in the Circus Maximus and dramatic performances. Two other features were a cavalry parade (equorum probatio) and a banquet in honor of Jupiter (epulum Iovis) at which the attendance of the gods (as at the chariot races and probably other events) was represented by the presence of their images (Livy 40.59.6–8; Dionysius of Halicarnassos Roman Antiquities 7.72.13; Ovid Amores 3.2.43–64).

From the late third century to the early second century BCE new annual ludi proliferated. The ludi Plebeii (Plebeian Games) were established in 220 and were celebrated each year in November. They were dedicated to Jupiter and included the same events as the ludi Romani. The ludi Apollinares (Games of Apollo) were established in 212 and, after an epidemic that struck Rome four years later, they were made an annual event with fixed dates in July (Livy 27.23.5–7). The creation of the ludi Megalenses (Games of the Great Mother, i.e., Kybele) was occasioned by the continuing presence of Hannibal in Italy (Livy 29.10.6). First held in 204, they immediately became an annual festival that took place in April. The last addition to the collection of regular ludi until the first century BCE was the ludi Florales (Games of Flora), a spring fertility festival that was first celebrated in 240 or 238; in 173 it was given annual status and a fixed date in late April to early May (Ovid Fasti 5.183–378). The ludi Florales, like all the other annual festivals, featured dramatic performances and chariot races (Taylor 1937: 285–6).

Ludi were steadily added to the Roman calendar. The nearly two and a half months of the year dedicated to games in the late first century BCE ballooned to a little less than six months by the middle of the fourth century CE (Veyne 1990: 399). It should also be noted that the list of annual ludi does not include extraordinary games given as one-time only events to celebrate special occasions. All these spectacles were financed by the state in combination with the magistrates who ran them and were provided to spectators free of charge. (For further discussion of ludi, see Chapter 40 in this volume.)

Chariot races featured prominently in Roman ludi for centuries. The infrastructure of Roman chariot racing presents a picture of a truly professional sport in comparison with the relative amateurism of Greek chariot racing, which depended on wealthy aristocrats to provide chariots, horses, and drivers. At least by the fourth century BCE, there was in place at Rome a system of four racing factions ( factiones) differentiated by their representative colors: white, red, blue, and green. The aristocratic owner of each faction (dominus factionis), in conjunction with a trusted manager (conditor), presided over a group of more than two hundred employees (Potter 2010: 308–25). The factions provided everything necessary for chariot races: horses, charioteers, and assistant staff like the hortator, an outrider who paced and encouraged a team of horses, and the sparsor, who cooled off the horses by sprinkling them with water. The charioteers, along with the rest of the staff, were either slaves or freedmen; in chariot racing, as in other forms of sport and spectacle, respectable Roman citizens were spectators, not participants (Edwards 1997: 67–76).

Chariot-racing fans were fiercely loyal to specific factions (Pliny Epistles 9.6). Fans had some attachment to individual charioteers including the great Gaius Appuleius Diocles, but drivers such as Diocles, like modern professional athletes, often switched teams (ILS 5287). The passionate allegiance of fans to specific factions is evident from the curses inscribed by them on lead tablets (defixiones), addressed to various malicious deities, asking them to cause the death of the horses and charioteers of opposing colors (Shelton 1998: 343–4; for more on defixiones, see Chapter 40). An oil dealer named Crescens proclaimed on his gravestone his loyalty to the Blue faction (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.9719). (For further discussion of chariot racing, see Chapters 33 and 43.)

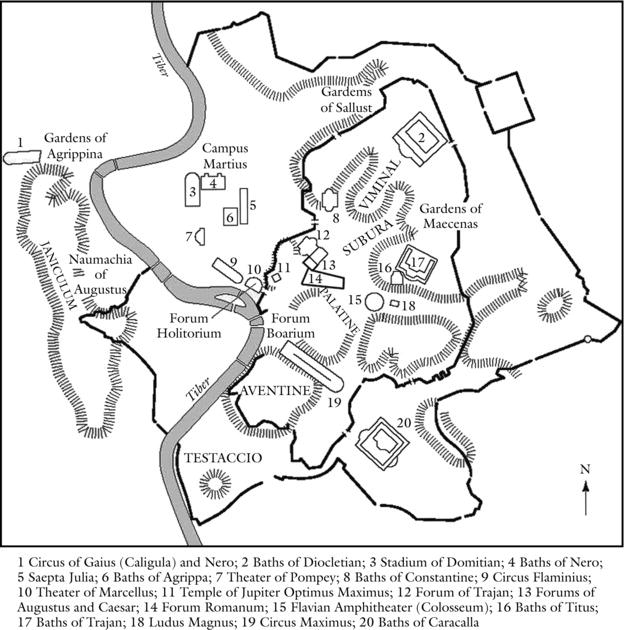

The primary venue for chariot racing in Rome was the Circus Maximus (see Map 25.1 for its location in Rome, Figure 25.1 for a reconstruction). In its final form this facility could seat approximately a hundred and fifty thousand spectators. The track at the Circus Maximus was built around a dividing barrier (spina or, more properly, euripus) decorated with objects such as obelisks, shrines, and seven “eggs” on sticks that were used to count laps. The most important function of the euripus was to prevent the sort of head-on collisions known to have occurred in Greek hippodromes, which lacked a dividing barrier (Sophocles Electra 681–756). At one end of the track, a structure containing 12 starting gates (carceres) was built with a slightly curved façade to minimize the disadvantage of those chariots assigned by lot to gates at either end and hence furthest from the euripus. The 12 gates, which probably used the same torsion system as catapults, were opened simultaneously with the pulling of one lever. The signal to pull the lever was given by the presiding magistrate, who dropped a piece of cloth (mappa) from a seating box located directly above an entrance that divided the starting gates into two groups of six. Once out of the starting gates, each chariot was confined to an assigned lane until it reached the nearest end of the euripus, where a white line stretched across the entire track. After passing that line, the charioteers could leave their lane and begin their move toward a more advantageous position as close as possible to the euripus. Races were run counterclockwise and typically consisted of seven laps. The finish line was about halfway down the euripus, on the right side (Humphrey 1986: 85–91; for more on Roman architecture associated with spectacles, including circuses, see Chapters 37 and 38).

The 12 starting gates allowed races consisting of one, two, or three entries from each of the four factions. When each faction entered more than one team of horses in a race, things got interesting. Shelton compares this kind of race to the modern American sport of roller derby in which teams of roller skaters race around a track (1998: 343, n. 229). One team for each faction in a double entry race and two in a triple entry race were assigned the task of helping the remaining team by hindering opponents. Although four-horse teams seem to have been the standard, there were also races of chariots drawn by two, three, six, or seven horses (ILS 5287). Other variations involved the pairing of two factions (Reds and Greens) as a team against the other two factions (Blues and Whites) and races in which desultores (vaulters) jumped back and forth between two horses (Livy 23.29.5; Balsdon 1969: 323; Potter 2010: 319–20). There was a special race called a diversium that took place after the day’s schedule was completed and seems to have been a showcase for star charioteers. In a diversium the winner of a race held earlier in the day would compete against an opponent he had defeated, after having exchanged horses with him (Cameron 1973: 133–4, 209).

Map 25.1 Plan of ancient Rome showing major spectacle sites.

Factions received payment for providing chariots and drivers for races and large cash prizes for winning. Prizes for victorious charioteers were both symbolic (palm and crown) and monetary. Faction owners paid their drivers a percentage of the prize money (Shelton 1998: 342–3, n. 230).

Figure 25.1 Reconstruction of the Circus Maximus in Rome. Source: Based on B. Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method (1921), p. 105.

After chariot racing, theatrical presentations (ludi scaenici) were the next oldest event held as part of ludi. The earliest ludi scaenici were imported from Etruria in the middle of the fourth century BCE and consisted of musical entertainments. They were later replaced by Latin adaptations of Greek tragedies and comedies, starting in 240 BCE with plays written by Livius Andronicus (Livy 7.2.1–11). At about the same time, the Atellan farce ( fabula Atellana), which featured buffoonish country characters, became part of Roman ludi. Two other dramatic forms, the fabula praetexta, a play based on Roman history, and the fabula togata, a play about Romans in everyday settings, soon took their places alongside Latin adaptations and the Atellan farce. Latin adaptations and the fabula praetexta seem to have remained the dominant forms of dramatic entertainment at Rome until the first century BCE. At that point, Roman dramatists evidently abandoned these two forms of drama, although revivals continued to be presented well into the Imperial period (Dio Cassius 61.17.3).

One replacement was the mime (mimus, a word also used for actors in the mime), which rapidly grew in popularity in the second half of the first century BCE and remained a key form of Roman drama through the third century CE and beyond. Mime was a departure from more formal traditional drama and was known for the “unbridled license” of its plots (Jory 1970: 241, n. 4). The mimus, unlike most other forms of drama, featured both male and female performers, without masks and in bare feet, acting out scenes from everyday life. Despite the modern meaning of the word, the mime included speaking parts. Mimes were presented at a number of different festivals, but were most closely associated with the sexually charged atmosphere of the ludi Florales (Valerius Maximus 2.10.8).

In the late first century BCE a new, more serious form of drama was introduced, which replaced dialogue with the interpretative dancing of a single actor. The actor, who played all the parts in the dramatic performance, was called a pantomime (pantomimus), and that name was eventually also used for this type of drama. The plots were for the most part derived from Greek mythology. An orchestra and chorus provided musical accompaniment. Despite their low social status and their tendency to stir up riots in the theater, pantomimes, because of their talent, consistently held places of honor in imperial circles (Cameron 1976: 223–4).

A spectacle featuring gladiatorial combats was known as a munus (duty or gift). In 264 BCE the first gladiator combat at Rome was presented at the funeral of Junius Pera by his son(s) (Livy Epitome 16; Valerius Maximus 4.6). Munera retained their association with funerals throughout the rest of the Republic and beyond. The munus, however, eventually acquired a connection with ludi, when magistrates in charge began to add gladiator games to the regular events as an enhancement.

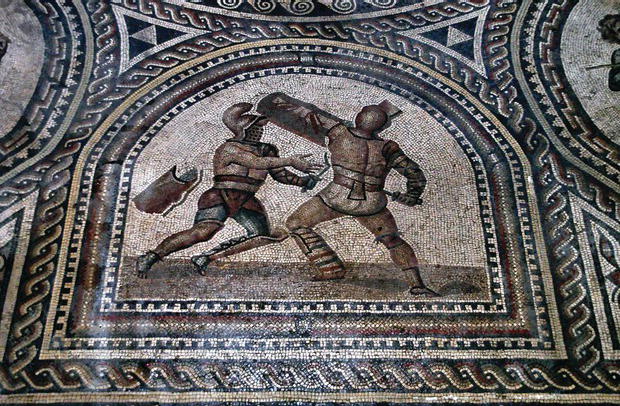

The rules of a gladiator duel were simple. A match could be won by one opponent killing the other, but this was not the only means of achieving victory. A gladiator was declared a winner if his opponent, by raising his index finger to the referee (summa rudis) or dropping any piece of armor on the ground, indicated that he was unwilling to continue. He was said to request missio (release) from the editor, the person in charge of the munus in question, which would allow him to fight another day. The editor, with the help of the crowd, decided whether he deserved to live or die. There was some honor in being granted missio, especially if the request for release came from a standing gladiator (stans missus) (ILS 5088). If the word missus was used without any qualification to describe the reception of missio, the assumption was that the request was made from a position kneeling, sitting, or lying on the ground, indicating that the losing gladiator had been beaten so badly that he was unable to stand. A gladiator who had acquitted himself well would probably receive missio, but if his submission was clearly motivated by cowardice or ineptitude, the decision of the editor was likely to be negative. The losing gladiator was then required to submit without resistance to a deathblow from his winning opponent, thus at least redeeming himself with a final act of bravery.

The possibility of a tie did exist, although it was a rare occurrence because both opponents had to request missio at virtually the same time (Martial Spectacles 31.81). The term used to describe a draw was stantes missi, the plural of stans missus. We also hear of gladiator duels sine missione (without release), but they seem to have been relatively rare (Potter 2010: 331). In fact, Augustus banned them, but that does not mean that his prohibition was always obeyed (Suetonius Augustus 45.3; Petronius Satyricon 45.6). Spectators could, therefore, not normally expect that every match would end in a death.

Modern attempts to calculate the fatality rate among gladiators are hampered by a lack of suitable evidence, diachronic change, and the reality that the odds of survival were different for each gladiator in accordance with the level of his skill and experience. The majority of inexperienced gladiators were killed in their first or second fights, whereas skilled and experienced fighters had much better chances of survival (Dunkle 2008: 140–3).

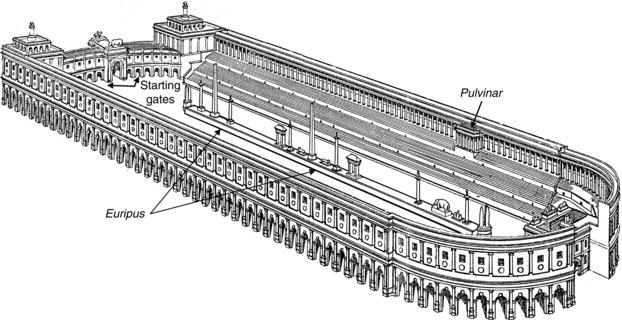

Figure 25.2 Mosaic from a Roman villa at Bad Kreuznach, Germany, showing gladiatorial combat between a thraex and murmillo, third century CE. Source: Photograph by Michael Eckrich-Neubauer. Used with permission.

All gladiators were not the same. They were divided into various types differentiated by their armor, weapons, and style of fighting, which was taught by a doctor (coach) in a ludus (gladiator school) (ILS 5110). For example, one of the earliest types of gladiator was the Samnite, named after an Italic people that Rome had defeated in the late fourth century BCE. Samnite gladiators adopted the armor and fighting style of Samnite warriors. It seems to have been the custom for Samnite gladiators and other early gladiators like the gallus (Gaul), eques (horseman), and provocator (challenger) to fight opponents of the same type. Horace mentions that a duel between two heavily armed Samnite gladiators often took up most of the afternoon (Epistles 2.2.98), indicating that the same armor and fighting style had a tendency to produce what must have been in many cases long, boring duels.

In the last century of the Republic, however, a new principle of pairing was introduced that matched up two gladiators of different types. The purpose of this innovation was to introduce more opportunities for strategy into the fights. There was a concerted effort to maintain fairness by making sure that any vulnerabilities created by an imbalance of armor and weapons were offset by counteracting advantages.

A classic case in point was the pairing of the thraex (Thracian) with the murmillo (no reliable translation) (see Figure 25.2). There were significant differences in the armor and weapons of these two gladiators. The thraex used a short curved sword called a sica, in contrast with the longer straight sword (gladius) of the murmillo. The murmillo wore a short metal shin guard only on his left leg, while the thraex wore metal guards on both legs that also protected the knees. In addition, the thraex had thick linen padding that extended from the top of the greaves to his loincloth (Junkelmann 2000a: 48–57). The reason for the extra protection for the thraex was the difference in the size of the shields wielded by these two gladiators. The large shield of the murmillo protected most of his body, while the shield of the thraex was less than half the size of his opponent’s. What advantage was given to the thraex to offset his small shield? The thraex, taking advantage of his curved sword, could reach around his opponent’s massive shield and stab him, causing a debilitating loss of blood (Aurigemma 1926: 169–70, fig. 101).

The difference in shield size of these two gladiators stirred up heated controversy among fans. Supporters of the large shield (scutum) were called scutarii, while those who preferred the smaller shield (parma) were parmularii. The debate reached up into the highest levels of Roman society, even involving the emperors Caligula, Nero, Titus, and Domitian (Suetonius Caligula 54.1, 55.2; Nero 30.2, 47.3; Titus 8.2; Domitian 10.1). In fact, this debate rose to a height of passion that paralleled the fierce loyalties to racing colors. Crescens, the passionate supporter of the blue racing faction mentioned earlier, also identified himself as a parmularius on his tombstone.

Gladiators were also paired up on the basis of their skill level in order to ensure relatively even matched fights. Originally this was done on an ad hoc basis by the people in charge of training gladiators and of running gladiator shows. By the end of the first century CE gladiators were assigned to one of four different grades: novicius (novice), tiro (trained recruit), veteranus (survivor of first fight), and palus, the highest ranked group, which itself was split into four different grades according to the gladiator’s level of training, experience, and success. An even more elaborate ranking system seems to have come into use in the second century (Potter 2010: 341–5).

Gladiators were for the most part convicted criminals, prisoners of war, and slaves. They were organized in troupes called familiae, trained by a lanista. For the most part their entrance into a gladiatorial familia was not voluntary but the result of a judicial sentence or through purchase. It was possible for a free man to volunteer to fight as a gladiator, in hope of financial rewards, and this seems to have happened more frequently as time went on. Although successful gladiators enjoyed a good deal of cachet, as might be expected in a society with a strong streak of militarism, the fact that they were slaves and performers meant that they were typically deprived of social status and many legal privileges. Cicero calls gladiators “either men of no moral worth or barbarians” (Tusculan Disputations 2.41). Lanistae, though typically free, were also low status individuals, whereas the owners of gladiatorial familiae tended to be wealthy aristocrats. Victorious gladiators received palm leaves and crowns as well as a portion of prize money offered by the organizers of munera. Manumission might be offered for particularly outstanding performances or for long service (Dunkle 2008: 30–40, 142–4). (For further discussion of gladiatorial combats, see Chapters 30, 31, and 32.)

The first mention of a staged animal hunt (venatio) is as one of the events of the games vowed to Jupiter Optimus Maximus by Marcus Fulvius Nobilior while on campaign and held in Rome as part of triumphal celebration in 186 BCE (Livy 39.22.1–4; Toynbee 1973: 17). This event featured lions and leopards, no doubt a great novelty at the time. During the Republic, the most frequent site of the venatio was the Circus Maximus. Although the venatio continued to be given occasionally at several sites in the Early Empire, including the Circus Maximus, it eventually fell under the umbrella of the munus and was presented in the amphitheater in the morning, while the gladiators fought in the afternoon. (On amphitheaters, see Chapter 37.) The combination of these two events became known as a munus legitimum (a proper munus).

The excitement of the venatio for the Romans lay in not just the bloody action but also in the opportunity to see animals from all over the Empire as a reminder of the vastness of their government’s domain (Martial Spectacles and Coleman 2006). The Roman crowd very seldom expressed pity or dismay because of the killing of these animals, although on one famous occasion elephants with their piteous trumpeting reportedly touched the hearts of the spectators (Cicero Letters to His Friends 7.1.3). It should also be noted that the Romans were in awe of the beauty and ferocity of animals they watched in the arena (Aulus Gellius Attic Nights 5.14.7). Whenever the opportunity presented itself, animals never before seen at Rome would be displayed as part of the venatio. Caesar in his triumphal games presented a “camelopard,” a hybrid neologism for the giraffe (Dio Cassius 43.23.1–2). As a demonstration of Roman mastery over wild nature, the venatio often featured performances of trained animals like lions, bears, and elephants (Seneca On Benefits 2.19.1). Perhaps the most memorable example of training was the amazing performances of dancing and dining elephants in Germanicus’s venatio of 6 CE (Dunkle 2008: 214–15).

The main human performer of the venatio was the venator (hunter), who wore a tunic and was armed with a long hunting spear or throwing spear. Bestiarii (literally, beast men) are generally regarded as assistants to the venator in the arena, but the term seems also to have been used of those convicts sentenced to suffer the ad bestias penalty ((to be thrown) to the wild beasts) (Seneca On Benefits 2.19.1). Venatores came from much the same sources as gladiators, and they were prepared for the arena in an institution called the Ludus Matutinus (Morning School) because of their presentation in the morning. Some, such as Carpophorus, became famous (Martial Spectacles 17, 26, 32).

Venatores went up against big cats and bears, large herbivores like elephants and boars, and even less dangerous animals like ostriches, deer, and wild asses (Junkelmann 2000a: 71). Deer and wild boars were also the prey of trained hunting dogs, some of whom became stars of the arena (Martial Epigrams 11.69). The venator, with his spears, probably had the advantage over his animal opponents but was himself sometimes killed by his adversaries. In fact, some animals won fame for themselves to the degree that they were given names, like the bear Omicida, (man killer, Toynbee 1973: 97).

The venatio also featured fights between animals. Bulls were often set against an elephant or a bear. In the ludi held to inaugurate the Colosseum in 80 CE, a rhinoceros fought a bull, bear, buffalo, bison, lion, and two steers (Martial Spectacles 11, 26). Animals often had to be chained together to spur them to fight.

As mentioned, another feature of the venatio was the execution of convicts (damnati) who were sentenced ad bestias. This harsh punishment was typically applied to criminals guilty of the worst crimes and to slaves. This manner of execution became even more popular as a spectacle because of a new category of damnati often subjected to this horrifying penalty, the Christians, whose unwillingness to worship the state gods often made them the object of special rancor (and sometimes pity) from the crowds (Potter 1993: 53–4). Occasionally executions in the venatio took on a more “artistic” form in which the victim was forced to play the starring role in a miniplay drawn loosely from Greek mythology (Coleman 1990). For example, on one occasion a convict playing Orpheus, known for his music’s mastery of nature, was torn to pieces by a bear (Martial Spectacles 24–5). (For further discussion of Roman spectacles involving animals, see Epplett’s essays on beast hunts and spectacular executions, Chapters 34 and 35, respectively.)

Because of the expense involved in its production, the staged sea battle or naumachia was reserved for truly special occasions (e.g., Rome’s millennium in 247 CE). Both Julius Caesar, for his triumphal celebrations and Augustus, for the dedication of the Temple of Mars Ultor in 2 BCE, created artificial lakes for their naumachiae, the first two ever given. We have no specific details about the size of Caesar’s naumachia beyond Suetonius’s comment that a “great number of fighters” took part ( Julius Caesar 39.4). We have more detailed information about Augustus’s sea battle, which involved 30 large ships and even more small vessels. On these ships were three thousand armed marines and an unspecified number of rowers (Augustus Res Gestae 23).

The grandest naumachia of all was given by the emperor Claudius outside of Rome on a natural lake (Lake Fucinus). The spectators sat on the lake shore and on a mountainside to view the event. There were nineteen thousand marines and rowers on a hundred ships in this epic battle. Participants in a naumachia were typically either damnati or prisoners of war and were expected to kill each other or drown (Dio Cassius 43.23.4). The fighters in Claudius’s naumachia spoke the famous words, “Hail, emperor, we who are about to die salute you,” mistakenly assigned to gladiators in so many films. Claudius, ever the jokester, added “or not,” holding out the hope of missio in return for a good performance (Dio Cassius 60.33.4; Suetonius Claudius 21.6). The damnati apparently thought that they would not have to fight, but they were forced by soldiers on rafts to engage each other in a fierce battle. They fought so well that survivors received pardons from Claudius (Tacitus Annals 12.56).

Nero gave two naumachiae in a new wooden amphitheater he had constructed: the first in celebration of the building’s dedication in 57 CE and another seven years later. The limitation of space inside the amphitheater required downsized vessels and a smaller number of fighters and rowers. In his first naumachia, Nero compensated for this drawback by presenting various sea creatures swimming in the water and showing off his ability to present another spectacle in the arena immediately after his naumachia (Suetonius Nero 12.1; Dio Cassius 61.9.5). The second naumachia was part of an even more impressive display of the switch between water and land, this time with a double dry/wet sequence: venatio/naumachia and gladiatorial combat/public banquet on a floating platform (Dio Cassius 62.15.1–5).

Both Titus and his brother Domitian are said to have staged naumachiae in the Colosseum, the former as part of the inauguration of the building in 80 CE (Dio Cassius 66.25.2; Martial Spectacles 27; Suetonius Domitian 4.1–2). Titus imitated Nero’s land/water switch by flooding the arena after an infantry skirmish. His intention seems to have been to outdo Nero when he placed in the water terrestrial animals (horses, bulls, etc.), which were trained to conduct themselves as if they were on land. There has been a long-standing debate about whether it was physically possible to flood the Colosseum and thus whether to take seriously the literary accounts purporting to describe naumachiae held in that building. Scholarly opinion was for a long time inclined toward doubt, but more recent work has suggested that in its early days the Colosseum could accommodate naumachiae (Coleman 1993: 58–60).

Beginning with the very first naumachia, it was the practice to provide an historical context for a sea battle, whether fictional or actual. For example, Caesar’s sea battle was between the “Tyrians” and the “Egyptians,” in all probability a product of his imagination. Augustus, Nero, and Titus preferred to represent real battles from Greek history: “Greeks versus Persians,” “Corcyraians versus Corinthians,” and “Athenians versus Syracusans.” Claudius’s “Sicilians versus Rhodians” was most likely unhistorical (Dunkle 2008: 192–201). Sponsors of naumachiae obviously wanted to stir the imagination of spectators by recreating the grandeur of the past, whether real or imagined. There was, however, a problem with presenting historical battles in the naumachiae. The outcome of the battle was unpredictable; the impersonators of historical winners could lose. In one of Titus’s naumachiae, the Athenians defeated the Syracusans, a reversal of history, indicating that it probably did not matter very much to the Romans who won (Dio Cassius 66.25.4). As we have seen, historical settings involving real battles were limited to Greek history. This limitation can be explained by the Romans’ reluctance to risk a loss by fighters representing Romans (Coleman 1993: 72–3). (For further discussion of naumachiae, see Chapter 38.)

The ludi of Marcus Fulvius Nobilior in 186 BCE were also the occasion of the first display of Greek athletics at Rome. These games probably consisted of a full complement of Greek athletic events: combat sports (boxing, wrestling, and pankration – a combination of boxing and wrestling) and the lighter track and field games (footraces and the pentathlon). This precedent does not seem to have warranted a repeat presentation of Greek athletics at Rome for almost a century and a half. In 55 BCE Pompey presented Greek athletics among his dedicatory ludi for his theater, the first permanent stone theater at Rome. The crowd’s reaction must have fallen below Pompey’s expectations because he complained afterwards of having wasted effort and money in acquiring oil for the athletes (with which they covered their body prior to competition) (Cicero Letters to His Friends 7.1.3). Perhaps the lighter athletic events were too tame for the Romans, who were used to violent action in their ludi. Caesar, for his triumphal celebration, built a temporary stadium in the Campus Martius for three days of Greek athletics (Suetonius Julius Caesar 39.3). There is no mention of the spectators’ reaction, but one wonders whether there was a better response than in Pompey’s show. Another problem for the Romans was their objection to Greek athletic nudity, which many feared would encourage homosexual activity among their youth (Cicero Tusculan Disputations 4.70; Tacitus Annals 14.20; for more on Roman criticisms of Greek sport, see Chapter 41).

Early in the Imperial period, however, Greek athletics began to enjoy wider acceptance at Rome, probably due in part to the promotion of Augustus, who in his Res Gestae mentions two spectacles he sponsored that consisted of athletes from all over the Empire. Later in the same document he puts Greek athletics on an equal level with gladiatorial combat, the venatio, and the naumachia as spectacles on which he has spent an immeasurable amount of money (22, summary). He also displayed great generosity to athletes, preserving and even increasing their much-prized privileges (Suetonius Augustus 45.3).

Greek athletics found a special champion in Nero, who created a Greek-style festival in Rome called the Neroneia, featuring musical, athletic, and equestrian contests (Suetonius Nero 12.3). Although this festival did not survive Nero’s death, Domitian instituted another set of athletic contests, the Capitoline Games, which were held in Rome starting in 86 CE. Not only did these games survive the assassination of Domitian, a most unpopular emperor, but they continued to be celebrated at least well into the third century CE and probably beyond (Dio Cassius 79.10.2; Newby 2005: 28–37). In 143 CE Antoninus Pius confirmed his father’s (Hadrian) grant of a meeting hall (curia athletarum) near Trajan’s baths in Rome for the use of members of a guild of Greek athletes during the Capitoline Games. The imposing name of this guild suggests the high status of its members: Xystic Synod of the Heraklean Athletic Winners of Sacred Games and Crowns (Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 1055b; on guilds see Chapter 6). (For further discussion of Greek sport in Rome, see Chapter 36.)

Spectacles enjoyed a long run of popularity as an essential part of Roman life, but by the early third century CE Christian writers were raising strident voices condemning the shows. Tertullian in his On Spectacles is a prime example. His objections include pleasure as damaging to a person’s morality (1.2–6), idolatry promoted by the games (4.3), lasciviousness of the theater (10.3–4), death as entertainment (12.1–4), madness in spectators of chariot races exacerbated by betting (16.1–2), and violence and vain displays of strength in Greek athletics (18.1–3). Despite these objections and later polemics, spectacles continued to be presented (although probably less frequently because of third-century political chaos) and were even attended by Christians. Imperial pressure during the fourth century, leading to the suppression of pagan ritual and sanctuaries by Theodosius I in the 390s, was no doubt the beginning of the end for the Roman spectacle (Mitchell 2007: 244–51). The ludi Megalenses, Cereales (games for the Italian fertility goddess Ceres), and Apollinares continued to be presented but no longer with their pagan titles (Balsdon 1969: 251). Some spectacles survived longer than others. Gladiator shows were the first to vanish, probably by the first quarter of the fifth century, while the venatio continued to be given for another century (Dunkle 2008: 201–6, 243–4). We last hear of theatrical presentations in the sixth-century author Cassiodorus (Variae 9.21.8). Chariot racing, which was much less controversial as far as Christianity was concerned, survived in Rome until the middle of the sixth century (Balsdon 1969: 252), while at the same time in Constantinople under Justinian it was enjoying its golden age. Economic troubles led to a continual decline of the sport after Justinian, which survived in a much diminished form at least into the tenth century (Cameron 1973: 256–8; see Chapter 43).

ABBREVIATIONS

ILS = Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae

NOTE

1 The numbering of the poems in Martial’s Spectacles in this chapter is that of Shackleton Bailey (1993).

REFERENCES

Aurigemma, S. 1926. I mosaici di Zliten. Rome.

Balsdon, J. P. V. D. 1969. Life and Leisure in Ancient Rome. New York.

Bernstein, F. 1998. Ludi publici: Untersuchungen zur Entstehung und Entwicklung der öffentlichen Spiele im republikanischen Rom. Stuttgart.

Cameron, A. 1973. Porphyrius the Charioteer. Oxford.

Cameron, A. 1976. Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium. Oxford.

Coleman, K. 1990. “Fatal Charades: Roman Executions Staged as Mythological Enactments.” Journal of Roman Studies 80: 44–73.

Coleman, K. 1993. “Launching into History: Aquatic Displays in the Early Empire.” Journal of Roman Studies 83: 48–74.

Coleman, K, ed. 2006. M. Valerii Martialis Liber Spectaculorum. Oxford.

Dunkle, R. 2008. Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Harlow, UK.

Edwards, C. 1997. “Unspeakable Professions: Public Performance and Prostitution in Ancient Rome.” In J. Hallett and M. Skinner, eds., 66–95.

Fagan, G. 2011. The Lure of the Arena: Social Psychology and the Crowd at the Roman Games. Cambridge.

Futrell, A. 2006. The Roman Games: A Sourcebook. Malden, MA.

Hallett, J. and M. Skinner, eds. 1997. Roman Sexualities. Princeton.

Humphrey, J. H. 1986. Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. Berkeley.

Jory, E. J. 1970. “Associations of Actors in Rome.” Hermes 98: 224–53.

Junkelmann, M. 2000a. “Familia Gladiatoria: The Heroes of the Amphitheatre.” In E. Köhne, C. Ewigleben, and R. Jackson, eds., 31–74.

Junkelmann, M. 2000b. “On the Starting Line with Ben Hur: Chariot-Racing in the Circus Maximus.” In E. Köhne, C. Ewigleben, and R. Jackson, eds., 86–102.

Köhne, E., C. Ewigleben, and R. Jackson, eds. 2000. Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Berkeley.

Manuwald, G. 2010. Roman Drama: A Reader. London.

Mitchell, S. 2007. A History of the Later Roman Empire, ad 284–641: The Transformation of the Ancient World. Malden, MA.

Newby, Z. 2005. Greek Athletics in the Roman World: Victory and Virtue. Oxford.

Potter, D. 1993. “Martyrdom as Spectacle.” In R. Scodel, ed., 53–88.

Potter, D., ed. 2006a. A Companion to the Roman Empire. Malden, MA.

Potter, D. 2006b. “Spectacle.” In D. Potter, ed., 385–408.

Potter, D. 2010. “Entertainers in the Roman Empire.” In D. Potter and D. Mattingly, eds., 280–349.

Potter, D. and D. Mattingly, eds. 2010. Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor.

Scodel, R., ed. 1993. Theater and Society in the Classical World. Ann Arbor.

Shackleton Bailey, D., ed. 1993. Martial Epigrams. 3 vols. Cambridge, MA.

Shelton, J.-A. 1998. As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History. 2nd ed. New York.

Taylor, L. R. 1937. “The Opportunities for Dramatic Performances in the Time of Plautus and Terence.” Transactions of the American Philological Association 68: 284–304.

Toynbee, J. M. C. 1973. Animals in Roman Life and Art. Ithaca, NY.

Veyne, P. 1990. Bread and Circuses: Historical Sociology and Political Pluralism. Translated by B. Pearce. London.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

The best place to start is with Futrell 2006 and Shelton 1998, both of which offer a combination of translated source material and excellent commentary. A handy supplement to both is Balsdon 1969, which covers a much greater number of sources, but with sparser discussion. Readers of German interested in a detailed scholarly analysis of ludi will find it in Bernstein 1998. Cameron 1973 and 1976 are seminal works that cover the history of chariot racing. Humphrey 1986 is a comprehensive study of circuses throughout the Empire and a seemingly inexhaustible source of information about chariot racing. A good introduction to Roman drama, including translations of excerpts from Latin plays, can be found in Manuwald 2010.

Dunkle 2008 is a good introduction to Roman gladiatorial combats that seeks to explain the Roman tolerance of lethal violence as entertainment by reference to cultural considerations. Fagan 2011 addresses the same subject from the perspective of social psychology. Edwards 1997 takes up the important social issue of the low status of performers and the participation of aristocrats and emperors as performers in spectacles. An introduction to the venatio can be found in Dunkle 2008: 207–44. Two indispensable articles by Coleman lucidly discuss the remarkable blend of entertainment and violent justice (1990) and the role of aquatic spectacles (1993) in imperial spectacle. In addition, Coleman 2006 has provided a major new translation and commentary on Martial’s Spectacles. Köhne, Ewigleben, and Jackson 2000 present a large number of excellent images that bring the Roman spectacle to life. Especially notable are Junkelmann’s fine contributions to that volume on gladiators and chariot racing (Junkelmann 2000a and b), the former fortified by his practical experimentation with gladiatorial armor and combat. On Greek sport in the Roman world, see Chapter 36 and Newby 2005.

Veyne 1990 is a valuable study of a phenomenon in the Greek and Roman world called “euergetism,” the public generosity of prominent individuals that was indispensable to the life of the spectacle. Potter 2006b and 2010 are essential reading, the first an interesting overview of Roman spectacle in six sections, of which the last two are especially recommended, while the second offers a detailed examination of the Roman entertainment industry.