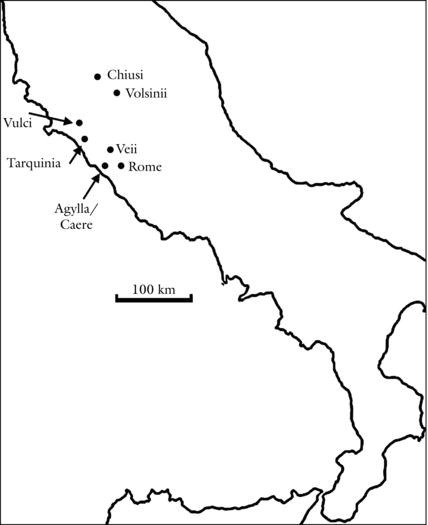

Map 26.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

In the first century BCE the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassos described the Etruscans as “a very ancient people resembling no other either in language or customs” (Roman Antiquities 1.30.2, trans. J. Kirkup). It remains true that we still have much to learn about this people, who lived in west-central Italy from the ninth century BCE onward.1 For instance, it is unclear if they were descended directly from the earlier indigenous population of the area or if, as many ancient Greeks believed, they immigrated to Italy from Asia Minor. A major difficulty is that Etruscan literary sources do not survive and, insofar as our understanding of the Etruscans’ language is far from complete, the many extant Etruscan inscriptions are less helpful than they might be.

It is not surprising then that, compared to Greece and Rome, our knowledge of sport in the Etruscan world is rather limited. References in Greek and Latin authors provide a modicum of information, and it is clear that in the Greek and Roman imaginary Etruscans were closely linked to sport. For example, the Greek historian Herodotus (1.94), in discussing the (ostensible) origin of the Etruscans in Lydia in Asia Minor, reports that, under the stress of famine, they invented games to help them forget their sufferings. In a similar vein, the Roman author Tertullian (On Spectacles 5.2) supplies a (probably spurious) etymology for the Latin word ludus (“game”) from “Lydis” (“from the Lydians”). However, Greek and Latin sources must be used with caution because they were not written by Etruscans and are by no means always accurate.

By far the most important source of information about Etruscan sport is visual evidence, most of it produced by and for Etruscans, which survives in considerable quantity and in various media ranging from ceramics to frescoes. Analysis of these images is the most promising method of learning about Etruscan sport.

However, iconographic analysis requires careful consideration of two major problems that concern the entire discipline of Etruscology. First, we must keep in mind the question of the complicated relationship between artistic images and reality: how much do images of Etruscan sport tell us about Etruscan games as they really were? How and how much does the purpose for which an object was made impinge on the fidelity of the representation it conveys? This problem can only be addressed through scrutiny of the social and physical contexts in which individual objects were used and found and requires an awareness of how individual objects taken together comprise an interrelated corpus of material that needs to be understood as a whole (Spivey 1997: 7–24).

The second major problem concerns the relationship between Greek and Etruscan culture. Etruscan visual culture was strongly influenced by Greek models and we must, therefore, consider the extent to which each Etruscan image reflects that influence. We must also give thought to the possibility that these images depart from Etruscan realities in order to appropriate Greek models. This issue is particularly acute when it comes to sport because it has been argued that Etruscan sport was heavily influenced by Greek sport (see the discussion in Thuillier 1997).

The nature of Etruscan sport and the relationship between Greek, Etruscan, and Roman sport and spectacle are the main subjects of this essay. Analysis of the representations of sport in Etruscan art shows that, even if they had a Greek iconographic model to which to refer, Etruscan artists did not follow it slavishly and were influenced by the factual reality of the competitions conducted in their culture. This underscores the degree of autonomy in Etruscan figurative art, which, even if clearly indebted to Greek art, never relinquished its own character. As Jean-Paul Thuillier rightly points out (1985: 410; cf. Thuillier 1997), we need not interpret everything in the Etruscan iconographic evidence for sport by reference to the relevant Greek material. There is, in fact, nothing to suggest that the sports played by the Etruscans were necessarily imported from other cultures. This does not preclude that they might have been shaped to some extent over the course of time by Greek influences. Nonetheless, these influences do not appear to have profoundly altered the original nature of these sports as they were played in Etruria. From its beginning, Etruscan sport shows characteristics that set it apart from its Greek equivalent indicating, therefore, a marked originality. In fact, there is, as we will see, good reason to believe that Etruscan sport was closer to Roman spectacle than Greek sport.

The following essay begins with a consideration of early depictions of Etruscan sport and then looks at events, equipment, the social status of athletes, and the social and physical contexts in which Etruscan sport took place. It will be helpful as we move forward to keep in mind that Etruscan history is typically divided by modern scholars into the following periods:

Although some of these periods bear the same names as the periods into which Greek history is divided by modern scholars, the chronology of Etruscan and Greek historical periods, even those with identical names, diverges in significant ways.

There are no clear representations of athletic activities in the Etruscan world prior to the Late Orientalizing period. The few images that can be dated earlier, artifacts from the Villanovan era in particular, are so ambiguous that a secure interpretation is not possible.

It is clear, however, that sport, particularly boxing and wrestling, was already part of Etruscan life by the end of the seventh century. Both boxing and wrestling are depicted on pottery and in bronze statuettes datable to the late seventh and early sixth centuries and thus appear to be the oldest sports in the Etruscan world.2 Datable to not much later (the beginning of the sixth century) are images of horse racing on terracotta slabs, which were found in the excavations of the so-called Palace of Murlo (Rathje 2004–7; Thuillier 1985: 82–7).3

The Etruscan iconographic evidence finds support in a passage from the work of the Roman historian Livy on King Tarquinius Priscus of Rome, whose reign is typically dated to around 600 and who was probably Etruscan. Livy (1.35.7–9) reports that, in order to celebrate a military victory, Tarquinius instituted games more splendid and sumptuous than those of prior kings of Rome. He also prepared a venue for these games, the Circus Maximus, complete with (probably wooden and temporary) grandstands for spectators from Rome’s ruling class. The games consisted of horse races and boxing matches, with the competitors brought in chiefly from Etruria. Livy’s account thus supports what we know from iconographic sources.

The number of extant images becomes noticeably greater during the Archaic period, in large part because of finds from the most famous cemetery at Tarquinia, one of the main Etruscan cities (see Map 26.1 for the locations of keys sites mentioned in this essay). That cemetery, known in the present day as Monterozzi, contains six thousand rock-cut tombs, most of which consist of a burial chamber accessed via a sloping or stepped corridor. Of the six thousand tombs at Monterozzi, roughly two hundred have elaborately painted interiors. The earliest of these date to the seventh century, but it was only in the sixth century that this style of decoration took hold and interiors were completely covered in paint.4

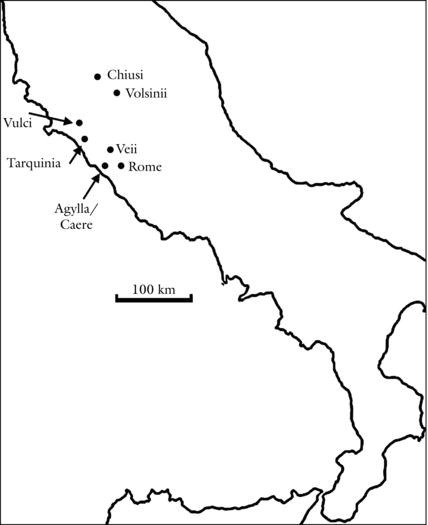

The Tomb of the Augurs, which is dated to 540–530, is one of the oldest and most important tombs at Tarquinia that contain depictions of sport. The paintings in this tomb include three sport scenes (Brendel 1995: 168–71; Steingräber 1986: 283). The left-hand wall of the rectangular burial chamber shows two nude boxers framed on one side by a flute player and on the other by a masked, bearded figure wearing a pointed cap, who is moving energetically (perhaps dancing or running?). On the far side of the right-hand wall a pair of nude wrestlers, one bearded and one beardless, is depicted, with a stack of three large basins (presumably the prize for the winner) between them (see Figure 26.1). To their left is a clothed male who is holding a curved rod, known in Latin as a lituus, and gesturing toward two birds flying over the wrestlers. The word TEVARATH is written over his head (though it has now faded due to the deterioration of the painting that occurred after the tomb was excavated). The lituus was closely associated with augury (interpreting divine will based on the flight of birds), so this figure is beyond doubt an augur. The most interesting of the three scenes in the tomb unfolds next to the wrestlers. Just to the right of the wrestlers is another masked, bearded figure wearing a pointed cap, over whose head was written the word PHERSU (likely the Etruscan word for “mask”). The masked man holds a long leash attached to a large dog. Between this man and the dog is another man, wearing only a loincloth, with a sack covering his head and a large club in his right hand. The dog is biting the thigh of the man with the sack on his head, who evidently is trying to defend himself with the club. Scholars typically refer to the activity shown in this scene as the “Phersu game.” Similar scenes have been found in a handful of other Etruscan tombs, including the Tomb of the Olympics at Tarquinia, and a single Etruscan black-figure vase.

Map 26.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

Figure 26.1 Wall painting from the Tomb of the Augurs at Tarquinia showing wrestlers and the “Phersu game,” c.540–530 BCE. Source: Photograph by Romualdo Moscioni (24 133), American Academy in Rome, Photographic Archive.

The scene of Phersu in the Tomb of the Augurs has provoked a great deal of scholarly debate, especially concerning its possible relevance to the origins of Roman gladiatorial combats. Lammert Bouke van der Mere (1982) cites the “Phersu game” as part of his argument that Roman gladiatorial games had an Etruscan origin. Paul Plass (1995: 57–8) sees a combination of gladiatorial combat and exposure to animals, with Phersu playing the role of a circus master orchestrating the violence. Jean-Paul Thuillier (1985: 338–40, 587–90; cf. Thuillier 1990) argues that the Phersu figure is acting as an executioner in an Etruscan version of the practice of exposing a doomed victim to a beast (damnatio ad bestias, on which see Chapter 35 in this volume). Georges Ville (1981: 2–6) feels that the “Phersu game” formed part of funeral games, that it was more footrace than bloodsport, and that the object was to spill blood and not to kill the man. Denise Rebuffat-Emmanuel (1983) suggests that the “Phersu game” was a sacred drama that reenacted Herakles’ descent to Hades and his struggle with Cerberus. Amalia Avramidou (2009) interprets this scene as a parody of the reenactments of the myth of Orpheus that took place as part of the rites of some mystery cults. It thus remains uncertain whether the scene represents a staged combat, execution, contest, drama, or some other form of performance.

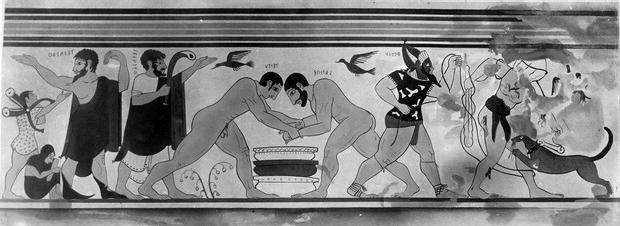

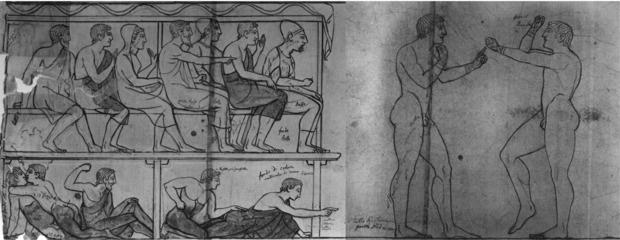

The paintings in three other tombs from Tarquinia include noteworthy sport scenes. The Tomb of the Inscriptions (540–530) contains scenes of boxing and wrestling as well as depictions of horsemen, who are perhaps waiting to participate in a race (Steingräber 1986: 314–5; Sannibale 2004: fig 5). Slightly later (530–520) is the Tomb of the Olympics, on the right-hand wall of which there are depictions of a nude discus thrower, a jumper, and three runners, as well as a heavily damaged depiction of the “Phersu game” (Brendel 1995: 268; Steingräber 1986: 328–9). The rear wall shows three naked runners and a naked jumper, the left wall a boxer and a race involving four two-horse chariots, one of which has crashed. Equally interesting but for a different reason is the Tomb of the Chariots (500–475; Brendel 1995: 266–9; Steingräber 1986: 289–91). Here the sport scenes, which feature nude athletes engaged in a variety of exercises including boxing and wrestling, are relegated to a small upper frieze. These scenes are framed by detailed portrayals of spectators. The audience sits on wooden bleachers, sheltered by an awning. Underneath the risers, there is a crowd of lower status individuals, probably slaves. The seated and elegantly dressed figures are probably of aristocratic rank. Among them are several female figures, some of whom occupy prominent positions. One woman in particular, given her position and her gesture, might even be understood as presiding over the games. This fresco demonstrates that women were present at Etruscan spectacles.5 Figure 26.2a and Figure 26.2b show drawings of the rear wall of the tomb, the paintings in which faded badly after excavation (for a fuller reproduction, see Sannibale 2004: fig. 6).

Figure 26.2a Drawing of the paintings on the rear wall of the Tomb of Chariots at Tarquinia showing athletic contests and spectators, c.500–490 BCE. Source: Based on O. Stackelberg and A. Kestner, Unedierte Gräber von Corneto (1830), pl. 2.

Figure 26.2b Detailed drawing of the painting in the upper left corner of the rear wall of the Tomb of Chariots at Tarquinia showing spectators and boxers. Source: German Archaeological Institute Rome (Schwanke, Neg. D-DAI-ROM 79.943 and 79.989).

The cemeteries at the Etruscan city of Chiusi have also produced remains dating to the Archaic period that contribute significantly to our understanding of Etruscan sport. The plentiful extant funerary markers (cippi, singular cippus) from Chiusi offer a number of sport scenes (Jannot 1984; Brendel 1995: 207–12).6 The tombs of Chiusi also boast frescoes with sports themes.7 Of particular interest are the paintings in the Tomb of the Monkey (c.480), which show a chariot race as well as two wrestlers, a javelin thrower, and two boxers, all nude (Brendel 1995: 274–7; Steingräber 1986: 273–4). The action takes place under the gaze of a woman seated beneath an umbrella. She is either the deceased person for whom games are being offered or the wife of the deceased, but either way she seems to preside over the games.

Boxing and chariot races are the two sports most often represented in Etruscan art. As far as boxing is concerned, the pictorial schema shows only minimal variation: a rather static image with two boxers facing each other in a guard position, with their fists, in leather wraps, lifted high in front of their faces. Sometimes a prize is shown between the two boxers. Blows are directed at the face; blows to the body are almost unknown. Thuillier believes that such brutal fights could not have lasted long. Toughness and physical strength, more than technique, determined the victor (1985: 243). To judge from the images, competitors were not matched based on age or weight. There is some controversy as to whether there was a sort of “ring” to delimit the space of the action. A flute player regularly appears in depictions of boxing matches, and it is probable that music punctuated the rhythm of the encounter.8

As for equestrian events, whereas we have pictorial documents of horse races from the beginning of the sixth century in the Murlo terracottas, the earliest extant depiction of chariot racing in Etruscan art occurs on a black-figure amphora dated to the middle of the sixth century (Bronson 1965: 95). Richard Bronson (1965: 94) asserts that “it is impossible to determine when, why or how chariot-racing was first introduced into Etruria. However, . . . its formal institution must have been of Hellenic inspiration.” Even if this is true, which is by no means certain, Greek influence was not so strong as to cancel out indigenous elements. Differences between Greek and Etruscan equestrian contests are noticeable in the clothing of the jockeys, the fashion in which charioteers secured their reins, and the type of goad employed. In Etruria, moreover, only two- and three-horse chariots were used, never four-horse chariots, which were common in Greek equestrian contests and which subsequently became the norm in Rome.9

Another discipline related to equestrian sport is that of the desultores, “horse dismounters,” of whom we find representations in Etruria from the sixth century onwards (Thuillier 1989a). In this event, acrobatic horsemen (or equestrian acrobats) combined horseback riding and footraces. A good example is found in the Tomb of the Master of the Olympiads (530–520) at Tarquinia (not to be confused with the Tomb of the Olympiads, Steingräber 1986: 321).

Wrestling was one of the first sports to appear in Etruscan art and, to judge from the number of depictions, was quite popular. The portrayal of wrestlers on Etruscan artifacts suggests that the Etruscan version of this sport did not differ markedly from its Greek counterpart; the primary goal was to throw one’s adversary to the ground. Unlike boxing, there is no evidence that music was played during wrestling matches. The number and geographical distribution of artifacts in Etruria suggests that in the town of Chiusi (inland eastern Etruria) wrestling was the favorite sport, whereas the residents of southern Etruria (specifically in Tarquinia) preferred boxing (Thuillier 1985: 283). This is a salutary reminder that there was a considerable amount of regional variation within the area of Etruscan settlement in Italy, so that generalizations can be made only with some caution.10

Depictions of all five components of the ancient pentathlon – jump, discus, javelin, wrestling, and running – are found in Etruscan art but they appear for the first time slightly after the earliest scenes of boxing and horse racing and are always comparatively infrequent. (Most of the relevant depictions appear on metal appliqués, as if this type of iconography was considered more appropriate for that type of artifact.) The just-cited Tomb of the Olympiads shows, in addition to chariot racing and the “Phersu game,” scenes of running, long jump, and discus. The paintings in the Tomb of Poggio al Moro in Chiusi (470–450) show four of the five standard Greek pentathlon disciplines (only the javelin throw is missing, Steingräber 1986: 271–2). In no instance are all five disciplines represented together in Etruscan art, but such depictions are rare in Greek art as well. According to Thuillier, because of the absence of literary texts or inscriptions, we cannot be certain that a true Etruscan pentathlon existed (2001: 16). Gigliola Gori (1986: 62), on the other hand, concludes that this composite discipline existed in Etruria. She believes, however, that in the Etruscan pentathlon the javelin was replaced by boxing (as it was later in the Roman certamen quinquertium).11

In Greek athletics, the pentathlon included the rough equivalent of a 200-meter dash, and footraces of varying lengths were held as stand-alone events. The evidence for footraces in Etruria is scanty and, if there was indeed an Etruscan pentathlon, it is impossible to know the length of the footrace that was held as part of that event or whether footraces were held as stand-alone events. A key problem is the absence of stadia, the venue for footraces in the Greek world. Moreover, no extant image portrays the start of a race, as a result of which it is impossible to tell how that was arranged in Etruria. There are very few images of runners wearing arms or armor, which suggests that the race-in-armor, the Greek hoplitodromos, was rarely held by Etruscans.

Other, albeit less popular, sports were also practiced in Etruria. There is a certain amount of visual and archaeological evidence suggesting that Etruscans held competitions in the shot put and the Tomb of the Chariots in Tarquinia preserves what appears to be a depiction of pole vaulting (Gori 1986: 47, 60; 1986/7).

Etruscan athletes are shown either naked or clothed in basic, practical garments. Nudity is found in Etruscan depictions of sport from the middle of the sixth century onward, particularly in works in which Greek influence is most visible. Therefore, the images do not unequivocally show that Etruscan athletes competed in the nude (Bonfante 2000; McDonnell 1993; Shapiro 2000). It appears that the Etruscans were familiar with athletic nudity but did not always practice it, probably for practical reasons. They wore a variety of garments suited to their physical exertions, including a short tunic with an attached skirt. Some Etruscan athletes seem to have used something like an athletic supporter, consisting of a sort of strap attached to a belt.12

The numerous finds of vases intended to hold olive oil and of strigils (curved scrapers used to remove oil from the skin after exercise) make it probable that Etruscan athletes, like their Greek counterparts, were in the habit of oiling their bodies. The use of oil is also confirmed by finds of mirrors with images of athletes using strigils. (Strigils, however, are not shown in Etruscan frescoes.) Olive oil, which was originally imported from Greece, was produced in Etruria starting sometime around the end of the seventh century. It is hard to say whether oil, as in Greece, was one of the prizes awarded to athletic victors; there are numerous depictions of vessels of various kinds offered as prizes for athletes but their contents are not made clear (Thuillier 1985: 353–61; Thuillier 1989b).

One cippus from Chiusi shows the moment of the awarding of prizes. Seated on a dais are the magistrates organizing the games and a scribe, who is most likely recording on a tablet the names of the winners. In front of them two athletes are waiting for their prizes (wineskins kept under the dais) (Colonna 1976).

Etruscan athletes show every sign of having been professionals of inferior social standing and seem to have formed a class of specialists directly employed by the Etruscan aristocracy (Thuillier 1985: 520–9). One might compare them to the artisans who decorated temples and tombs or to the various artists, such as dancers and actors, who provided entertainment at religious festivals. Livy tells a story about a king of the Etruscan city of Veii who, having been angered, brought contests being held at the sanctuary of Voltumna to a halt when “he suddenly withdrew the performers, most of whom were his own slaves [servi], in the middle of the games” (5.1.4, trans. C. Roberts). Livy’s use of the term servi does not imply that athletes lived in materially worse conditions than those of the penestes, free men working in agriculture or mining (Heurgon 1964: 57–9). On the contrary, they may have enjoyed better living conditions. It must have been in the Etruscan master’s interest to take good care of his athletes, in order to obtain better performance. Moreover, although there can be little doubt that athletes were not typically people of high social status, it is not certain that they were all slaves (Thuillier 1985: 522–29, 689–92).

We cannot ascertain what Etruscan athletes did in “retirement.” Because they were professionals of low status, Etruscan athletes were not buried with honors or with the instruments of their profession. In a very few tombs images of athletes record their names (e.g., the two wrestlers in the Tomb of the Augurs, above whose heads are written TEITU and LATHITE), which implies that some athletes developed a certain level of fame. However, no Etruscan inscription records the entire career of an athlete, something that was common in the Greek world. The Etruscan words whose meanings are known and that refer to sport, such as SUPLU or SUBLO (flute player, Heurgon 1964: 188) and TEVARATH (someone who presides over a contest), designate persons who had functions relating to the competition, not to athletes themselves (Thuillier 1985: 541–8). One might speculate that retired athletes trained and managed those still actively competing, and it is logical to suppose that the best Etruscan athletes would have had a greater chance of manumission.

The relatively low status of athletes in Etruria stood in sharp contrast to the situation in Greece. Sport was an activity that, in most times and places in the Greek world, was closely associated with free men of relatively high status. There is nothing to suggest that members of the Etruscan aristocracy participated in athletic contests, as they did in Greece.13 And even if young aristocrats participated in horse races or other disciplines, that cannot be generalized to Etruscan sport overall.

Etruscan sport was closely linked to funeral rites. The funerary games portrayed with great frequency in Etruscan art are a key moment in the funerary rituals held for members of the Etruscan elite. Analysis of the visual evidence suggests that those rituals had four basic components: the prothesis (the laying out of the corpse), a banquet, games, and shows (dances and plays). Most of the evidence for Etruscan sport comes from funerary contexts, the walls of tombs and the sides of grave markers in particular. The most obvious explanation for this phenomenon is that these depictions served as records of the funeral ceremonies, including games that were held in honor of the deceased. Several scholars have plausibly conjectured (see, for instance, Holloway 1965 and Stopponi 1983: 62–4) that the structure of the burial chambers in Etruscan tombs imitates a tent for spectators, thus reproducing the pavilion from which the members of the nobility observed funeral ceremonies. Sport scenes appear alongside banqueting scenes, which suggests that the banqueters are also the spectators at the spectacles (athletic contests, plays, and dancing) that were held at funerals. On the walls of the tomb are depicted the events that the spectators would have seen from the tent. (Even differences in the size of the figures shown in the paintings might reflect the perspective of spectators looking out of the tent.) “The funeral ceremony is thus recorded not only in the painting of the banquet, the dances, and the games, but even in the re-creation of the setting of these events” (Thuillier 1985: 638). Reproducing the ceremony in the art decorating the tomb ensured the permanent reiteration of the rite, in order to extend its efficaciousness for all eternity.

It is clear that the funeral ceremonies immortalized on the walls of tombs were the privilege of a very exclusive social class and served to mark the high status of the deceased and of his or her family. We must also not lose sight of the fact that in Tarquinia, only a few of the painted tombs, which themselves comprise about 2 percent of all the burial sites, show images of games. This may suggest that most if not all tombs painted with sport scenes belonged to city magistrates, who were the only people whose funeral games were worthy of memorialization (Benassai 2001).

That would in turn suggest that the funerals at which much Etruscan sport took place were at least to some extent public rather than private events. Thuillier notes that “if the pomp of the ceremonies reflects on certain aristocratic families and reinforces their prestige, the fact that the dead were sometimes magistrates of their city, the fact that the entire apparatus of public power . . . could accompany the procession, the fact that the entire population attended these games gave a clearly public character to these spectacular celebrations” (1996: 35). The example of the Tomb of the Chariots is revealing; the presence of the public on the stands and slaves underneath shows that these games exceed the private sphere of a single family. Rita Benassai calls them “a conspicuous event in the community of Tarquinia,” in which “the deceased most likely held a special role. Probably he was a magistrate who himself had organized games, or had presided over them as the highest political functionary” (2001: 245).

Beyond the athletic contests held as part of noble burials, we may consider two other types of games: those organized by towns and those organized by federations that linked together the various Etruscan cities.14 The evidence for the existence of games organized by individual Etruscan towns is tenuous. Herodotus (1.167) states that sometime around the middle of the sixth century the residents of the Etruscan town of Agylla (more properly known as Caere) stoned to death a substantial number of Greek prisoners of war and that, afterwards, animals and humans passing the site of the slaughter became paralyzed. The Agyllans (ostensibly at least) consulted with Delphi and were told to make recurring sacrifices to the dead and to hold horse races and other sports contests in their honor.15 We have already seen that Livy (1.35.7–9) reports on Tarquinius Priscus, an Etruscan king of Rome, founding games and building the Circus Maximus. These two passages do not constitute a substantial body of evidence, but we might well imagine that every town would have celebrated its principal deity, or the deities of the most important sanctuaries, and that those celebrations would have involved games.

As for games organized by Etruscan federations, the only certain source is the so-called Rescritto di Spello (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 11.5265), an inscription that records a decision of the Roman emperor Constantine I and that dates to the first half of the fourth century CE. This inscription attests to the existence of games held annually by a league that linked together 12 of the most important Etruscan cities.16 These games were evidently held near the town of Volsinii, at the sanctuary of Voltumna, likely the patron deity of the league. The annual assembly probably ceased to exist after 264, the year in which the Romans destroyed the town of Volsinii, but resumed in some form at a later date, and the Rescritto di Spello inscription refers to these new festivities. The text of the Rescritto actually mentions plays and gladiatorial combats (and not sport contests), but we have no way of knowing what took place originally.17 Thuillier believes that the introduction of gladiatorial combats must have been a later addition, which supplanted earlier and more typically Etruscan boxers and wrestlers (1985: 431).

A passage from Livy (5.1.4) referenced above provides some clarification of the nature of the events held at the sanctuary of Voltumna before 264. Livy reports that during a war between Rome and the Etruscan city of Veii, the people of Veii opted to elect a king as their leader but that he was not particularly beloved because of his arrogance. Livy provides as an example of his undesirable behavior an episode that happened at the sanctuary of Voltumna near Volsinii. This king of Veii had not been elected sacerdos (a title which most probably refers to the priest-magistrate who represented the league of Etruscan cities at the sanctuary), and he decided, out of spite and in disrespect of the sacredness of the rites, to withdraw his slaves from the games, thus interrupting their progress.

The Rescritto di Spello and the passage from Livy thus point to the existence of athletic contests organized by a league linking together the 12 main Etruscan cities. Some scholars have hypothesized that there were also smaller leagues, which also organized games.

All the different contexts in which Etruscan sport took place had a strong religious valence (Thuillier 1985: 419–60). This is made clear by the presence in numerous sport scenes of figures carrying a lituus (the curved rod associated with augurs). The lituus was a key symbol of religious and political authority in Etruria, and the person who carried it was a priest-magistrate. In the context of representations of sport he is the TEVARATH, the person who presides over the contest (the equivalent of an agonothetes in Greece). He is not, therefore, simply a referee. The referee exists, but holds a different instrument: a long staff, bifurcated at one end. The terracotta slabs from Murlo illustrate the difference. In one of them both figures are present: the TEVARATH, seated on a throne, carrying the symbol of authority, and the referee, standing with his long staff in hand. The first figure could be seen as a kind of dominus, an overlord, who presides over the games and whose religious function is underscored by the lituus. He is accompanied by another standing figure, who carries his weapons, symbols of his military might; the dominus has temporarily set aside his weapons to take up the lituus, thus emphasizing the different roles he plays at different moments.

Representations of sport in Etruscan art strongly suggest that games were held in the open countryside and, in the case of funeral games, probably not far from the cemetery. There is nothing that indicates the existence of large buildings in urban settings that were used for sport. This explains the habitual depiction of stylized trees in scenes that include sport: they evoke an outdoors setting.

Games that did not involve chariot races seem to (in some cases at least) have taken place in terraced areas near the tomb of the deceased person in whose honor athletic contests were being held. Some tombs at Tarquinia dating to the seventh century include a theaterlike structure in the form of a large pathway, resembling a small piazza, that leads to the tomb and that is often framed by steps, which were presumably intended to accommodate spectators (Colonna 1993). In the sixth century some tombs at Blera and Vulci exhibit the same feature. The example most often noted is the space in front of the Tomb of Cuccumella (570–550), a sort of small private “stadium.” However, it is important to keep in mind that these were multipurpose structures and surely not exclusively dedicated to athletic activities.

There is in Etruria no archaeological evidence whatsoever for the existence of permanent structures dedicated to games (Thuillier 1985: 347–9). And, despite the profound Hellenization of Etruscan culture, neither are there signs of the existence of two quintessential Greek sports venues: the palaistra and the gymnasion (on which see Chapter 19). Moreover, whereas Greeks created specialized buildings for different types of competition (stadium and hippodrome), Etruscans seem to have used a single space for all different kinds of sport, a space that was something like a primitive version of the later Roman circus (Thuillier 2001: 17–18). These were simple open areas, provided with temporary wooden seating, where any type of competition could be held. It is therefore not so strange that no Etruscan equivalent to the Circus Maximus in Rome has yet been discovered. We do not know enough of the topography of Etruscan cities to be able to say so with certainty but, as Giovanni Colonna has noted, “in every large Etruscan city one can make out level areas suited to horse and chariot-races” (1993: n. 172).

Although there was considerable overlap in regard to events and equipment, Greeks and Etruscans had radically different conceptions of sport. Scenes of sport and spectacle in Etruscan art frequently have grotesque overtones, and this renders the Etruscan depictions very different in spirit from the Greek representations. The closest parallels to the “Phersu game,” if it, as seems most plausible, should be understood as some kind of violent spectacle, are not to be found in the Greek world.

It is important to emphasize that Etruscan games were above all spectator sports; everything was done in Etruria to please those who watch. In the audience we find the ruling classes, decked out with symbols of their power, enjoying the show; on the field of competition we find the athletes, professionals of low social standing. In contrast to Greece, sport in Etruria was not a privileged locus for status competition by free men. We do not have a complete picture of Etruscan sport, but it is clear that “the Etruscan situation is closer to Rome than to Athens” (Thuillier 1985: 612).

From the end of the fifth century, there is a clear change in Etruscan iconography. The scenes of games fade away and almost disappear. Can we consider their diminishment in the fifth century as a sign of impoverishment of the Etruscan ruling class? The games must have cost a lot; maintaining a troupe of athletes was surely onerous for Etruscan aristocrats. In less favorable economic conditions, it is possible that the organization of games, particularly those paid for by individual families, became much rarer. But the spirit of the Etruscan games did not die; it passed gradually to the Romans. Roman spectacle is the true heir of Etruscan sport.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to thank Paul Christesen for offering me the opportunity to contribute to this volume and for his assistance in improving my essay both in content and form, as well as Professor Monika Otter of Dartmouth College for her assistance in translating this article into English.

NOTES

1 All dates in the remainder of this essay are BCE unless otherwise indicated.

2 The relevant objects include, but are by no means limited to, a bucchero vase from Veii (c.630) with a representation of two boxers (Thuillier 1985: 57–65; Sannibale 2004: fig. 1) and two bronze statuettes from Murlo (c.600) showing a wrestler and a referee (Thuillier 1985: 70–7; Warden 1982; Sannibale 2004: fig. 4).

3 These slabs show three jockeys, dressed in cloaks and pointed hats, riding galloping horses bareback. The prize, a bronze cauldron, is placed on top of a column. For a detailed stylistic analysis of this plaque, see Root 1973.

4 On Etruscan tombs in general, see Brendel 1995: 43–8. For detailed analysis of the Tarquinian tombs, see Steingräber 1986 and 2006.

5 On the relatively elevated status of Etruscan women, see Haynes 2000: 125–6, 133, 255–9.

6 The production at Chiusi of cippi, rectangular bases decorated with low reliefs, carved in the local limestone, started some time after the middle of the sixth century. The bulk of the material belongs to the Late Archaic and Early Classical periods, approximately between 520 and 470. The production died out some time after the middle of the fifth century (Jannot 1984; Brendel 1995: 116, 179, 207–12).

7 Fewer than twenty painted tombs have been discovered so far in the territory of Chiusi, most of them dating to the first half of the fifth century. It seems likely that they were decorated by Tarquinian workshops, and offer above all images of funerary rituals (banquets, dances, and games). On Chiusi painted tombs, see also Rastrelli 2000.

8 On Etruscan boxing, see Thuillier 1985: 179–268. Thuillier (1985: 208–53) considers a number of different explanations for the regular association of flute players and boxers in Etruscan art.

9 On equestrian competitions in Etruria, see Bronson 1965 and Thuillier 1985: 81–110.

10 On Etruscan wrestling, see Thuillier 1985: 269–87.

11 On the Etruscan pentathlon, including details of the individual events included in the pentathlon, see Thuillier 1985: 269–328.

12 This practice is similar but not identical to the infibulation known from the Greek world, see Thuillier 1985: 374–8. It is illustrated with particular clarity in the Tomb of the Monkey at Chiusi (Brendel 1995: 274–7; Steingräber 1986: 273–4).

13 Sannibale (2012: 127) has argued that – at least in the Tomba delle Iscrizioni at Tarquinia – the knights are members of the same aristocratic gens that built the tomb. Etruscan tombs have yielded a huge quantity of Panathenaic amphorae (on which see Chapter 5 in this volume). There is, however, no reason to believe that the persons buried in these tombs won these vases as prizes for competing in the Panathenaic Games at Athens; the vases are simply imported luxuries from Greece, just like many other items found in Etruscan cemeteries (Moretti 2003: 17–19; Sannibale 2012: 126).

14 The terracotta plaques depicting images of games found in Murlo may attest to another type of games not connected with funerary rites. They might record celebrative ceremonies held in princely residences. “The overlord, the dominus, of Murlo might have summoned on a regular basis – or even for exceptional events – his clients . . . to partake to festivals of a different kind [than funerary]” (Thuillier 1985: 434).

15 On this passage in Herodotus, see Asheri, Lloyd, and Corcella 2007: 187–8.

16 On the Etruscan League, see Haynes 2000: 135–7.

17 On the Rescritto di Spello, see Coarelli 2001.

REFERENCES

Asheri, D., A. Lloyd, and A. Corcella. 2007. A Commentary on Herodotus: Books I–IV. Oxford.

Avramidou, A. 2009. “The Phersu Game Revisited.” Etruscan Studies: 73–87.

Barbet, A., ed. 2001. La peinture funéraire antique: IVe siècle av. J.-C.-IVe siècle ap. J.-C. Paris.

Barker, G. and T. Rasmussen. 1998. The Etruscans. Oxford.

Becatti, G., ed. 1965. Studi in onore di Luisa Banti. Rome.

Benassai, R. 2001. “La Tomba delle Bighe a Tarquinia. Immagine di un aristocratico tarquiniese di V sec. a.C.” In A. Barbet, ed., 243–7.

Bloch, R., P. Boyancé, and A. Alföldi, eds. 1976. L’Italie préromaine et la Rome républicaine. Mélanges offerts à Jacques Heurgon. 2 vols. Rome.

Bonfante, L. 1986. Etruscan Life and Afterlife: A Handbook of Etruscan Studies. Detroit.

Bonfante, L. 2000. “Classical Nudity in Italy and Greece.” In D. Ridgway, ed., 271–293.

Borrelli, F. 2004. The Etruscans. Art, Architecture and History. Los Angeles.

Brendel, O. 1995. Etruscan Art. 2nd ed. New Haven.

Bronson, R. C. 1965. “Chariot Racing in Etruria.” In G. Becatti, ed., 89–106.

Centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo, ed. 2001. Umbria cristiana: Dalla diffusione del culto al culto dei santi, secc. IV–X. 2 vols. Spoleto.

Coarelli, F. 2001. “Il rescritto di Spello e il santuario ‘etnico’ degli umbri.” In Centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo, ed., 1: 39–51.

Cohen, B., ed. 2000. Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art. Leiden.

Colonna, G. 1976. “Scriba cum rege sedens.” In R. Bloch, P. Boyancé, and A. Alföldi, eds. 1, 187–95.

Colonna, G. 1993. “Strutture teatriformi in Etruria.” In J.-P. Thuillier, ed., 321–47.

D’Agostino, B. 1989. “Image and Society in Archaic Etruria.” Journal of Roman Studies 79: 1–10.

Domergue, C., C. Landes, and J.-M. Pailler, eds. 1990. Spectacula, I: Gladiateurs et amphithéâtres. Paris.

École Française de Rome, ed. 1993. Spectacles sportifs et scéniques dans le monde Étrusco-Italique. Rome.

Futrell, A. 1997. Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power. Austin, TX.

Garelli, M.-H., ed. 2010. Corps en jeu: De l’antiquité à nos jours. Rennes.

Gori, G. 1986. Gli Etruschi e lo sport. Urbino.

Gori, G. 1986/7. “Etruscan Sports and Festivals.” Stadion 12/13: 9–16.

Haynes, S. 2000. Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. Los Angeles.

Heurgon, J. 1964. Daily Life of the Etruscans. Translated by J. Kirkup. New York.

Holloway, R. R. 1965. “Conventions of Etruscan painting in the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing at Tarquinii.” American Journal of Archaeology 69: 341–7.

Izzet, V. 2007. The Archaeology of Etruscan Society. Cambridge.

Jannot, J.-R. 1984. Les reliefs archaïques de Chiusi. Rome.

Jannot, J.-R. 1993. “Phersu, phersuna, persona: À propos du masque étrusque.” In J.-P. Thuillier, ed., 281–320.

Jannot, J.-R. 2005. Religion in Ancient Etruria. Translated by J. Whitehead. Madison.

Mandolesi, A. and M. Sannibale, eds. 2012. Etruschi. L’ideale eroico e il vino lucente. Milan.

McDonnell, M. 1993. “Athletic Nudity among the Greeks and Etruscans.” In École Française de Rome, ed., 395–407.

Moretti, A. M. 2003. Lo sport nell’Italia antica: Immagini nel percorso del museo. Rome.

Pallottino, M. 1975. The Etruscans. Translated by J. Cremona. 2nd ed. Bloomington.

Plass, P. 1995. The Game of Death in Ancient Rome: Arena Sport and Political Suicide. Madison.

Rastrelli, A. 2000. “Le tombe dipinte.” In A. Rastrelli and E. Benelli, eds., 154–65.

Rastrelli, A. and E. Benelli, eds. 2000. Chiusi etrusca. Siena.

Rathje, A. 2004–7. “Murlo, Images, and Archaeology.” Etruscan Studies 10: 175–84.

Rebuffat-Emmanuel, D. 1983. “Le jeu du Phersu à Tarquinia, nouvelle interprétation.” Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres: 421–38.

Ridgway, D., ed. 2000. Ancient Italy in its Mediterranean Setting: Studies in Honour of Ellen Macnamara. London.

Root, M. C. 1973. “An Etruscan Horse Race from Poggio Civitate.” American Journal of Archaeology 77: 121–37.

Sannibale, M. 2004. “Sports in Etruria: The Adoption of a Greek Ideal between Reality and Symbolism.” In N. Stampolidis and G. Tassoulas, eds., 81–101.

Sannibale, M. 2012. “I giochi e l’agonismo in Etruria.” In A. Mandolesi and M. Sannibale, eds., 123–37.

Shapiro, H. A. 2000. “Modest Athletes and Liberated Women: Etruscans on Attic Black-Figure Vases.” In B. Cohen, ed., 313–37.

Spivey, N. 1997. Etruscan Art. New York.

Stampolidis, N. and G. Tassoulas, eds. 2004. Magna Graecia: Athletics and the Olympic Spirit on the Periphery of the Hellenic World. Athens.

Steingräber, S. 1986. Etruscan Painting. New York.

Steingräber, S. 2006. Abundance of Life: Etruscan Wall Painting. Translated by R. Stockman. Los Angeles.

Stoddart, S. 2009. Historical Dictionary of the Etruscans. Lanham, MD.

Stopponi, S. 1983. La tomba della “Scrofa Nera.” Rome.

Thuillier, J.-P. 1981. “Les sports dans la civilisation étrusque.” Stadion 7: 173–202.

Thuillier, J.-P. 1985. Les jeux athlétiques dans la civilisation étrusque. Rome.

Thuillier, J.-P. 1989a. “Les desultores de l’Italie antique.” Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres: 33–53.

Thuillier, J.-P. 1989b. “Les strigiles de l’Italie.” Revue archéologique: 339–42.

Thuillier, J.-P. 1990. “Les origines de la gladiature: Une mise au point sur l’hypothèse étrusque.” In C. Domergue, C. Landes, and J.-M. Pailler, eds., 137–46.

Thuillier, J.-P., ed. 1993. Spectacles sportifs et scéniques dans le monde étrusco-italique. Rome.

Thuillier, J.-P. 1996. Le sport dans la Rome antique. Paris.

Thuillier, J.-P. 1997. “La Tombe des Olympiades de Tarquinia ou Les jeux étrusques ne sont pas les concours grecs.” Nikephoros 10: 257–64.

Thuillier, J.-P. 2001. “Peintures funéraires et jeux étrusques. L’exemple de la Tombe des Olympiades à Tarquinia.” In A. Barbet, ed., 15–19.

Thuillier, J.-P. 2010. “Le corps de l’athlète (Grèce, Étrurie, Rome): Représentations et ‘realia.’” In M.-H. Garelli, ed., 339–50.

Torelli, M. 2000. The Etruscans. Milan.

van der Mere, L. B. 1982. “Ludi scaenici et gladiatorum munus: A Terracotta Arula in Florence.” BABESCH 57: 87–99.

Ville, G. 1981. La gladiature en Occident, des origines à la mort de Domitien. Rome.

Warden, P. G. 1982. “An Etruscan Bronze Group.” American Journal of Archaeology 86: 233–8.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

The body of modern scholarship on Etruscan sport is not nearly as extensive as that on Greek sport, but much fine work has been done. The most comprehensive study remains Thuillier 1985, to which this essay is greatly indebted. Thuillier (1985: 119–75) provides a complete catalog of all the relevant iconographic sources with full bibliography for each source. See also Thuillier 1981, 1989a and b, 1990, 1997, 2001, and 2010, all shorter pieces that deal with more specialized questions regarding Etruscan sport. Another sizeable and important study can be found in Gori 1986 (cf. Gori 1986/7).

On Etruscan history, see Haynes 2000. Pallottino 1975, although somewhat out of date, remains helpful. On Etruscan civilization in general, see Torelli 2000 and Barker and Rasmussen 1998. On the daily life of the Etruscans, see Heurgon 1964 or Bonfante 1986. Stoddart 2009 is a basic but useful dictionary of Etruscan civilization. On the archaeological evidence for Etruscan society and history, see Izzet 2007. On Etruscan religion, see Jannot 2005. Introductions to Etruscan art can be found in Borrelli 2004 and Spivey 1997, cf. Torelli 2000, which includes numerous photographs. On Etruscan wall painting in general and the tombs at Tarquinia, perhaps the single most important source for Etruscan sport, see Steingräber 1986 and 2006. On grave markers from Chiusi, see Jannot 1984; on tomb paintings from Chiusi, see the relevant sections in Borrelli 2004 and Steingräber 1986 and 2006. On the reasons why sport scenes were included in Etruscan tomb paintings, see D’Agostino 1989. Sannibale 2004 contains a detailed review of the iconographic evidence for Etruscan sport, along with a perhaps too credulous analysis of that evidence. See also now Sannibale 2012.

On the dress of Etruscan athletes, see Bonfante 2000; McDonnell 1993; and Shapiro 2000. The “Phersu game” has been much discussed. Some, but by no means all, of the relevant scholarship includes Avramidou 2009; Futrell 1997:14–16; Jannot 1993; Plass 1995: 57–8; Rebuffat-Emmanuel 1983; Thuillier 1985: 338–40, 587–90; van der Mere 1982; and Ville 1981: 2–6.