Figure 29.1 Bronze gladiator’s helmet from Pompeii, first century CE. Source: British Museum GR 1946.5–14.1, © Trustees of the British Museum.

What can material evidence tell us about ancient sport and spectacle that literary accounts and artistic images cannot? As a simple thought experiment, pretend that you could pick up one of the near-perfectly preserved 2,000-year-old gladiator helmets that have been found at Pompeii and place it over your head (see Figure 29.1). Imagine the disorienting way in which your vision would be fragmented and restricted by having to peer through tiny holes in the mesh covering your face. Consider how sounds and voices would be muffled and distorted within the hemisphere of bronze enclosing your head. Feel the solid weight of the helmet bearing down on your neck and shoulders, making every movement clumsy and exaggerated, and the sharp, acrid smells of bronze and your own sweat filling your nostrils. Admittedly, the insights to be gained from such an experiment are relatively minor – we can capture one tiny aspect of the physical experience of being a gladiator, specifically how one’s helmet restricted one’s senses, and from this we can perhaps extrapolate other information, such as the effects this might have had on fighting techniques.

Nevertheless, this fragment of sensory experience, trivial as it might seem, is something that no ancient literary text tells us. Almost all surviving literary and much of the artistic evidence regarding Roman sport and spectacle was produced by and/or intended for the consumption of a tiny group of elites, but these were not the groups that either participated in or, in terms of numbers, constituted the overwhelming majority of observers at these events. We simply do not have any first-hand written description of what it was like to be a gladiator or a charioteer. Similarly, we lack any accounts whatsoever from the millions of ordinary Romans who constituted the vast majority of spectators. These are huge and troubling voids in our knowledge of ancient sport and spectacle. It is precisely here, however, in this crucial gap of knowledge, that material evidence represents a vital resource that can at least partially begin to recover these missing voices and experiences.

Figure 29.1 Bronze gladiator’s helmet from Pompeii, first century CE. Source: British Museum GR 1946.5–14.1, © Trustees of the British Museum.

One key category of material evidence consists of the surviving objects that were actually used by those who either participated in or observed ancient sport and spectacle. Physical items such as the equipment employed by gladiators, the programs scrutinized by ancient circus fans, and the regalia carried in triumphal processions can all serve as starting points toward reconstructing not just the literal course of ancient events but, more importantly, the attitudes and experiences of the participants and observers. Another absolutely vital type of material evidence comprises epigraphic sources (inscriptions), notably tombstone epitaphs and graffiti, because it is only through these that we can come close to recapturing the lost voices of those most directly involved in ancient spectacle. Humble cultural objects such as toys, lamps, pots, and flasks are invaluable in assessing societal attitudes toward ancient performers and the place that they held in popular culture and consciousness. Additionally, there are other types of inscriptions and physical evidence, such as official proclamations, laws, and coins, that, while representing a more elite perspective, nevertheless also have much to contribute. Finally, even items such as their bones can reveal surprising insights into both the professional activities and the day-to-day lives of ancient performers. This essay will present a brief overview of some broad categories of material evidence for sport and spectacle in the Roman world and will discuss several particularly notable, recent, or informative examples.1

In attempting to understand ancient sport and spectacle, items such as the helmet mentioned above are appealing because they appear to offer more visceral and direct access to the experiences of ancient performers than the sort of secondary constructs we find in literature and art. Dozens of gladiatorial helmets in various stages of preservation survive, as well as a variety of other types of body armor, including many greaves and some shoulder guards (see Junkelmann 2000: 161–87). By studying the form and function of these objects and combining this information with visual and textual evidence, we can reconstruct much about the practical aspects of gladiatorial combat.

A natural next step is to fashion replicas of the equipment used by gladiators, athletes, and charioteers and attempt reenactments of ancient agonistic spectacles. While such reconstructions have long been practiced as entertainment by Hollywood and even in live contexts such as the chariot races staged for tourists at Jerash, Jordan, more recently there has been a spate of more rigorously scholarly reenactment projects exploring both the equipment utilized by ancient performers and the tactics that arise from their particular characteristics. Within the last decade, elaborate projects in Germany and France have meticulously recreated entire gladiator schools complete with accurate copies of equipment for an array of different types of gladiators and have experimented with various combat styles and situations as described in sources and portrayed in ancient images (Junkelmann 2000; Teyssier and Lopez 2005). Such academic reenactments seem only to be increasing in popularity, with a gladiator project having been run at the University of Regensburg during the summer of 2010.

As entertaining and useful as such reenactments can be in understanding the practical details of ancient spectacles, they are not as informative in illuminating the attitudes or emotions of Roman performers and spectators. This is not to say that it is utterly impossible to tease out social implications from the examination of physical objects such as gladiatorial arms and armor. One study, for example, has cleverly been able to discern aspects of Roman cultural self-identity centered around traditional military virtues based solely on a close comparison of the equipment of gladiators and legionaries (Coulston 1998).

If we turn from performers to spectators and from pragmatics to attitudes, one rather specialized set of physical objects that eloquently testifies to the intense passions aroused by ancient performances is curse tablets. More than 80 defixiones, or lead curse tablets, have been found which invoke supernatural forces against actors, wrestlers, pantomime artists, and, most commonly, charioteers. In some cases the tablets are even directed against charioteers’ horses and have been found hidden near the starting gates or in the stables of circus complexes. One such tablet, from Carthage, reads in part:

Bind the horses whose names and images I have entrusted to you [23 horses’ names follow]. Bind their running, their power, their soul, their onrush, their speed. Take away their victory, entangle their feet, hinder them, hobble them, so that tomorrow morning in the hippodrome they are not able to run or walk, or win, or go out of the starting gates, or advance either on the racecourse, or circle around the turning point, but they may fall with their drivers. (CIL 8.12508, translation from Gager 1992: 60–2)

One could also attempt to use magic to ensure victory or ward off spells, as the following recipe indicates:

I adjure you angels of running, who run amid the stars, that you will gird with strength and courage the horses that N is racing and his charioteer who is racing them. Let them run and not become weary nor stumble. Let them run and be swift as an eagle. Let no animals stand before them, and let no other magic or witchcraft affect them. (translation from Gager 1992: 59)

Defixiones such as these not only indicate the close identification that spectators felt with the fortunes of their favorite factions or performers, but reveal that some fans further believed that they could take an active role in affecting the outcome of competitions. Given the amount of gambling that seems to have accompanied chariot racing, a fan’s investment in the victory of his favored team may have been more than just an emotional one. These tablets suggest the intense engagement (on several levels) that spectators sometimes felt with performers and help to explain the great popularity of such phenomena as Roman chariot racing.

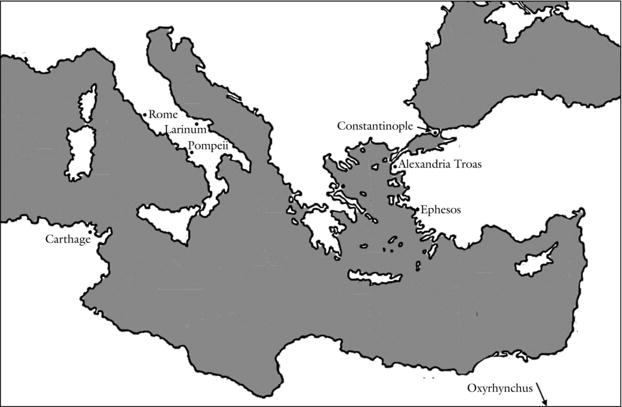

While literary sources tend to focus on exceptional spectacles that were unusual for their scale and expense, such as Trajan’s astonishing 123 days’ worth of games to celebrate his triumph over Dacia during the course of which supposedly 11,000 wild beasts were slain (Dio Cassius 68.15.1), a much more realistic and modest portrait of a typical day’s worth of events is offered by a papyrus, found in Oxyrhynchus in Egypt (see Map 29.1 for the locations of key sites mentioned in this essay) and dating to the sixth century CE, which preserves the following program of entertainments in the local circus: “First chariot race. Parade. Singing rope dancers. Second chariot race. The singing rope dancers. Third chariot race. Gazelle and hounds. Fourth chariot race. Mime show. Fifth chariot race. Troupe of athletes. Sixth chariot race” (Oxyrhynchus Papyri 2707).2 Similarly, monuments erected by proud local magistrates at Pompeii describing the games that they provided reveal a relatively restrained program of entertainments; for example, one man’s sponsorship of the ludi Apollinares included paying for a parade, some bulls and bullfighters, three pairs of gladiators, a group of boxers, and some musical pantomimes (CIL 10.1084d).

As has been noted by many scholars, the ancient Romans possessed the “epigraphic habit,” meaning that they had a strong predilection for inscribing a wide range of nonliterary texts in stone and erecting monuments bearing these inscriptions. Why, how, and when this habit became established and why it flourished are fascinating questions revealing much about Roman society, but are well beyond the scope of this essay. For now, we can only be grateful that the Romans went to the trouble of leaving such a quantity of information in such a durable format. These inscriptions represent a wide spectrum, from emperor to slave, in terms of the social class of the people who composed them, and include both official imperial proclamations and more personal messages, such as tombstone epitaphs. To these inscriptions can be added a number of other types of short texts, most notably messages scratched onto fragments of pottery, or onto walls as graffiti. These communications offer something extremely rare that more famous literary texts or art objects cannot – a glimpse of the hopes, dreams, opinions, and aspirations of common Romans. For the study of sport and spectacle, texts such as tombstone inscriptions are especially useful because many of them were composed or erected by people with personal ties to ancient performers, usually their families or their professional peers, thus bringing us tantalizingly close to the thoughts of groups who are otherwise silent or marginalized in upper-class sources.

Map 29.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

Some graffiti is clearly the work of Romans who were avid fans and thereby offer direct contact with the perspectives and feelings of ordinary people who watched these events. Of this type are probably the three crude sketches recording a series of gladiator fights, scratched on a tomb outside of Pompeii. The fan includes drawings of the different gladiators fighting and adds labels listing their names, previous records, and the outcome of the combats (CIL 4.10236–8; see Jacobelli 2003: 50–2, for images and discussion). Perhaps the reason that this spectator was moved to memorialize these events in such detail was because this apparently was a remarkable show in which the veteran gladiator Hilarus, survivor of 14 combats and victor of 12, was shockingly defeated by Marcus Attilius, a novice fighter. In the same way that modern sports enthusiasts are sometimes obsessed with tracking the statistics of their favorite athletes, graffiti such as this one attest to a similar phenomenon among ancient fans, whose scribblings frequently list information such as the number of fights or races won. (For an even more extensive example of a graffito consisting of a wearyingly long set of fight statistics, see CIL 4.2508.) In other instances, the graffiti, such as those found in structures identified as gladiator barracks, seem to have been authored by the gladiators themselves. Some of these grant us valuable clues as to their own self-image, as when one Pompeian gladiator identifies himself as “Celadus, the Thracian, who makes the girls sigh” (CIL 4.4397).

If we are trying to strip away the public façade and get a sense of the person behind the performer, however, perhaps no form of evidence speaks as eloquently as their grave markers. These were often erected by loved ones or peers, and, while obviously still presenting a constructed image and likely an idealized one at that, these monuments capture aspects of the performers’ humanity and their roles outside the arena. For example, one gravestone featuring a carving of a child holding the reins of a two-horse chariot reads, “I, Florus, rest here, a child driver of two-horse chariots, who wanted to race swiftly, but more swiftly fell into darkness. Iarnuarius made this for his most sweet foster-son.” (ILS 5300). Often it is a woman self-identified as a wife (whether legally recognized or not) who has been responsible for raising a monument to her lost lover: “To the departed spirit of Marcus Antonius Niger, veteran gladiator of the Thracian style, who lived 38 years and fought 18 times. Flavia Diogenis made this monument for her husband at her own expense because he deserved it well” (ILS 5090). Finally, grave monuments were commonly put up by one’s fellow performers, perhaps attesting to the strong bonds of friendship that often are forged by communal experience and by collectively facing danger: “Flamma, a secutor, lived 30 years, fought 34 times, was victorious 21 times, received missio standing 9 times, received missio 4 times, a Syrian by birth. Delicatus made this for a deserving comrade-in-arms” (CIL 10.7297; ILS 5113). (On missio, see Chapter 25.)

There are, in addition, several other types of inscriptions that, although produced by elites, have been central to our understanding of both the details of staging ancient spectacle and its societal status and role. Senatus consulta, or official decrees of the Roman Senate, were not infrequently inscribed on stone or bronze tablets, and several of these have been especially important sources of information on ancient sport. One well-known example is a decree of 19 CE found at Larinum in Italy, which places stern restrictions on participation in any form of public performance by members of the Roman upper classes (Levick 1983). The decree is an explicit and vivid reiteration of the idea that performance on the stage or in the arena constitutes dishonor (infamia) and even the mildest association with such activities on the part of senators or equestrians is in serious “contravention of the dignity of their order.” Nevertheless, this document also brings out the underlying tension that, despite the social odium attached to these activities, they plainly possessed an irresistible allure. References in this senatus consultum to the passage of earlier laws prohibiting such participation indicate that these efforts were either unsuccessful or deemed to require reinforcement.

Another particularly informative senatus consultum dating to 177 CE represents an effort by the emperor Marcus Aurelius to regulate and limit the cost of presenting gladiatorial shows (CIL 2.6278; Carter 2003). That this decree was viewed as important legislation is perhaps attested by the fact that the two surviving copies of it were discovered at diametrically opposite ends of the Roman Empire, suggesting an attempt at universal enforcement. By this time, a hierarchy of gladiators had developed, ranging from the novicius, who was still in the initial training phase, up through the tiro, who was judged ready for his first fight, to the veteranus, who had fought at least once and survived, followed by four more ascending grades of experienced gladiators culminating in the top rank of primus palus. Marcus Aurelius’s senatus consultum of 177 builds off this structure to establish an elaborate system of maximum costs, setting down how much could be spent on various classes of gladiators as a function of the overall expenditure on a particular set of gladiatorial games. This text speaks to the elaborateness of the organizational structure of the ancient spectacle industry, as well as illustrating concerns about the costs of regularly staging these shows.

Exciting, newly discovered inscriptions continue to illuminate hitherto unknown aspects of ancient performances. For example, fragments of several letters from the emperor Hadrian to the Wandering Guild of Dionysiac Artists were found in 2003 in Alexandria Troas in what is now Turkey (Petzl and Schwertheim 2006; English translation available in Potter and Mattingly 2010: 352–71). A lot of these texts consist of the emperor reaffirming specific rights of the actors (many of which also seem to apply to athletes) in regard to various contractual issues, usually involving money. Among many other provisos, it is spelled out that prizes must be paid in cash, not in goods such as wine or grain, that prizes must still be distributed if a contest is canceled or interrupted, and that the prize money must be displayed at the contest. An interesting passage addressing a nonmonetary concern states that while it may be necessary to strike contestants with whips in some contexts, such floggings should not be excessively brutal. Another letter lays out a grand reorganization of the entire quadrennial calendar of major agonistic competitions. It establishes a schedule for the staging of the traditional Greek Panhellenic festivals as well as various prominent games in cities in Italy and elsewhere. These remarkable documents offer insights into the sorts of concerns that performers had, as well as the degree to which the emperor could become involved in the micromanagement of local disputes.

A set of commemorative inscriptions for ancient performers that perhaps deserve special mention consists of several that were erected in honor of especially successful charioteers. The most notable of these is an inscription found at Rome describing the career of a second-century CE champion charioteer named Gaius Appuleius Diocles (CIL 6.10048 = ILS 5287; see, similarly, the sixth-century CE monument in Constantinople to Porphyrius Calliopas, extensively analyzed in Cameron 1973). In the course of enumerating Diocles’ considerable achievements during his long and extraordinarily successful career, the inscription offers a wealth of information about many different aspects of chariot racing. Like modern champion athletes, star charioteers could apparently switch teams, as Diocles at various points raced for the Reds, Whites, and Greens. (On chariot racing, see Chapter 33.) His total career winnings topped 35 million sesterces, a vast sum and one that indicates the wealth to which successful athletes could aspire. Among the myriad statistics recorded are that he won 1,462 victories over the course of a 24-year career and competed in races driving chariots with two, three, four, six, and even seven horses. Successful chariot-racing strategies are suggested by other statistics, such as the fact that 815 of his victories came from seizing the lead at the outset of a race and holding it, 502 from winning a sprint at the end of the race, and only 67 from coming from behind to overtake the leader.

Why would someone want an image of one human murdering another engraved on the flask he or she drank from, or stamped onto the lamp that illuminated his or her home? Why would a representation of a despised slave be considered an appropriate form in which to cast a candlestick holder? Another category of material evidence consists of everyday objects that are decorated with images of sport and spectacle. Like the other material types discussed, these can be particularly useful for what they reveal about the attitudes of the ordinary Romans who were the main consumers of ancient spectacular performances. Images of scenes from the circus or amphitheater are a common feature of humble and often mass-produced household objects. While the range of such objects is considerable, encompassing basic items such as cups, flasks, plates, jewelry, mirrors, and even toys, I will consider just one representative example in this essay: the near-ubiquitous oval, clay lamp.

Some of these lamps are actually molded so as to imitate the form of various pieces of equipment used by performers, such as a number of extant lamps in the shape of helmets. Others bear depictions of weapons or, more commonly, of solitary gladiators or charioteers (or even, in one case, a prize horse) standing triumphantly after a victory. However, the decorations on a great number of these lamps focus on scenes of action and explicit violence. Thus, on different lamps, we see a wrecked charioteer being gruesomely trampled beneath the sharp hooves of a rival’s horses, or a savage lion snarling as it leaps onto a terrified horse’s back, or a disarmed gladiator standing helplessly as he waits for his victorious opponent to plunge a sword into his exposed body (see Figure 29.2). (All of the lamps mentioned in this paragraph are illustrated and briefly discussed in Köhne, Ewigleben, and Jackson 2000: 37–8, 47, 51, 73, 86, 88, 101, 128, 131, 135).

Much is often made of the apparent similarities between Roman and modern sport and spectacle, but objects such as these lamps embody crucial differences. That such graphic and voyeuristic images of violence would be considered appropriate and unremarkable choices for decorating common household goods is a useful reminder that there are aspects of the value system of the Romans that, from a modern perspective, do indeed represent a sense of true “otherness.” For example, in the city where I live, I could easily purchase and display in my living room, to universal approval, a lamp molded in the shape of a football gaudily emblazoned with the colors of the local team. However, were I to replace it with one cast in the form of one man knifing another (or even, say, a tiger disemboweling a rhinoceros) this would certainly draw many disapproving comments. Not only do such objects illuminate key aspects of Roman social values but they also highlight some of the tensions latent in the system as well. Many scholars have fruitfully explored the status dissonance created by the fact that while gladiators could enjoy great fame and popularity and even embodied some core Roman ideals of masculinity and military prowess, they were simultaneously despised for their servile status and for employing their bodies in the amusement of others. (On such issues, see, for example, Barton 1993; Wiedemann 1992; Futrell 1997; and Potter 2010.)

Figure 29.2 Roman clay lamp from London (made in Gaul or Britain) showing gladiatorial combat, first century CE. Source: British Museum P&EE 1856.7–1.336, © Trustees of the British Museum.

Another type of cultural object that encapsulates many values in relation to ancient spectacles is the coins and commemorative disks minted by the Roman state. Roman numismatics is a complex field, and any interpretation of the images or slogans on a coin raises problematic issues of intent and audience. But one area in which coins can be especially instructive is in determining the appearance and decorative schemes of the structures used to stage public entertainments. Coins showing the arrangement of statues on the façade of the Colosseum or the profusion of monuments in the Circus Maximus in Rome are one of the best sources of information for reconstructing how these famous buildings looked to the performers and spectators who used them. Also, the mottos selected to be stamped onto coins commemorating specific festivals can tell us how the sponsors of these events desired them to be perceived. Thus, a coin celebrating the truly spectacular Secular Games put on in 204 CE by Septimius Severus bears, on one side, the emperor’s profile and, on the other, an image of the enormous ship he placed in the circus, which, upon a signal, disgorged hordes of exotic animals. On the coin, surrounding the representation of this truly spectacular event, is the label “Laetitia Temporum” (“Happy Times”). (On Roman coins depicting structures used for sport and spectacle, see Hill 1989 and Tameanko 1999. For an alternative interpretation of this coin, see Bingham and Simonsen 2008.)

Analysis of the images on coins can also sometimes hint at more subtle aspects of attitudes toward ancient performance. For example, many coins depicting events in the amphitheater or circus show these scenes from an artificial bird’s-eye perspective that no actual spectator could have enjoyed. Furthermore, the scenes often conflate several different chronological moments in an attempt to create a kind of continuous and all-encompassing narrative. Such images encourage a psychological perspective in which the action of the performance and the experience of the spectator are linked to grander cycles or structures of time and community (see Bergmann 2008).

One of the more exciting recent discoveries that has revealed completely new types of information about Roman gladiators was the 1993 identification and subsequent excavation of a cemetery exclusively containing the bodies of gladiators at the city of Ephesos in modern Turkey. Because of the low social status of gladiators, they were a stigmatized group, and so it is not surprising to find that they were buried apart from others in a specially designated area. Archaeologists have been able to identify 67 bodies from this graveyard who seem to have been gladiators, all but one of whom were young males between the ages of 20 and 30. (All specific facts in this section are taken from Kanz and Grossschmidt 2002 and 2006.)

By examining marks on their bones, it is possible to identify both old trauma injuries that had healed as well as ones that had not and which thus were presumably inflicted at or near the time of death. These marks offer direct evidence of the sorts of injuries that gladiators suffered, indicate the types of weapons that inflicted them, and even suggest how these weapons were employed. A surprising number of injuries were to the skull, emphasizing the face-to-face nature of gladiatorial combat. For example, 16% of the individuals displayed well-healed head injuries, with nearly half of these exhibiting multiple healed wounds. The location and nature of many of these injuries indicate that they were the result of repeated blows to the wearer’s helmet, while others seem to have been inflicted directly by strikes from a bladed weapon such as a sword. 15% of the men in the graveyard had unhealed skull injuries, indicating that these were either the cause of death or else happened very close to the time of death. Some of these are massive blunt force trauma injuries such as might have been caused by being struck with a shield. One of the most interesting consists of a pair of perforations of the skull whose diameters and spacing strongly suggest that the injuries were inflicted by a trident, the characteristic weapon of the retiarius type of gladiator. A number of fatal blows to the skull also seem to have been made by a square hammer, a weapon known to be used in the arena to dispatch fatally wounded gladiators. Notches on bones in the spine and shoulder blades indicate other types of killing blows administered with a sword. The knee of one man bore a very unusual injury consisting of four dents in a square pattern, a wound which can be matched up to a specialized gladiator weapon with four prongs. By examining these bones we gain vivid knowledge of the causes of death and injury to gladiators and thus we can better understand the course of these ancient combats.

Gladiators’ bones can reveal much more information than just how these men died; they can also tell us vital facts about how they lived. For example, isotopic analysis of their bones has revealed that they ate a mostly vegetarian diet that was rich in carbohydrates. One slang term for gladiators was hordearii, or “barley boys,” and this scientific analysis confirms that gladiators indeed probably ingested large quantities of grains. On such a diet, gladiators may have carried substantial layers of fat that actually would have helped them survive superficial cuts and slashes by blanketing vital organs and vessels under a thick fatty stratum.

By applying such modern scientific procedures to this ancient evidence, it is possible to glean new types of information that flesh out the old images of gladiators that we have long held, primarily derived from the traditional literary sources. Other possible gladiator burials have come to light, and as fresh archaeological discoveries and even newer technologies become available, there is hope that we may be able to gain yet further knowledge from such material evidence as these old bones.

ABBREVIATIONS

CIL = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

ILS = Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae

NOTES

1 Sports activities and athletic competitions, including the great quadrennial athletic festivals such as the Olympic Games, continued into the Roman era (see Chapter 36), but here I will concentrate for the most part on the more distinctively Roman forms of sport and spectacle, with particular attention to gladiatorial combat, which today is undoubtedly the most famous, and on chariot racing, which was probably the most popular and frequently attended by ordinary Romans.

2 Unless otherwise indicated, all translations of ancient texts were produced by G. Aldrete.

REFERENCES

Attridge, H. W., J. J. Collins, and T. H. Tobin, eds. 1990. Of Scribes and Scrolls: Studies on the Hebrew Bible, Intertestamental Judaism, and Christian Origins Presented to John Strugnell on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday. Lanham, MD.

Barton, C. 1993. The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster. Princeton.

Bergmann, B. 2008. “Pictorial Narratives of the Roman Circus.” In J. Nelis-Clément and J.-M. Roddaz, eds., 361–92.

Bingham, S. and K. Simonsen. 2008. “A Brave New World? The Ship-in-Circus Coins of Septimius Severus Revisited.” Ancient History Bulletin 20: 51–60.

Cameron, A. 1973. Porphyrius the Charioteer. Oxford.

Cameron, A. 1976. Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium. Oxford.

Carter, M. 2003. “Gladiatorial Ranking and the SC de Pretiis Gladiatorum Minuendis (CIL II 6278 = ILS 5163).” Phoenix 57: 83–114.

Cooley, A., ed. 2000. The Epigraphic Landscape of Roman Italy. London.

Coulston, J. 1998. “Gladiators and Soldiers: Personnel and Equipment in ludus and castra.” Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies 9: 1–17.

Curry, A. 2008. “The Gladiator Diet.” Archaeology 61: 28–30.

Desnier, J.-L. 1990. “Les représentations du cirque sur les monnaies et les médailles.” In C. Landes, ed., 81–90.

Elkins, N. 2006. “The Flavian Colosseum Sestertii: Currency or Largess?” Numismatic Chronicle 166: 211–21.

Futrell, A. 1997. Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power. Austin, TX.

Futrell, A. 2006. The Roman Games: A Sourcebook. Malden, MA.

Gager, J. 1990. “Curse and Competition in the Ancient Circus.” In H. W. Attridge, J. J. Collins, and T. H. Tobin, eds., 215–28.

Gager, J. 1992. Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World. New York.

Garraffoni, R. 2008. “Gladiators’ Daily Lives and Epigraphy: A Social Archaeological Approach to the Roman munera during the Early Principate.” Nikephoros 21: 223–41.

Heintz, F. 1998. “Circus Curses and Their Archaeological Contexts.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 11: 337–42.

Hill, P. 1989. The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types. London.

Hope, V. 1998. “Negotiating Identity and Status: The Gladiators of Roman Nîmes.” In R. Laurence and J. Berry, eds., 179–95.

Hope, V. 2000. “Fighting for Identity: The Funerary Commemoration of Italian Gladiators.” In A. Cooley, ed., 93–113.

Humphrey, J. H. 1986. Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. Berkeley.

Jacobelli, L. 2003. Gladiators at Pompeii. Rome.

Junkelmann, M. 2000. Das Spiel mit dem Tod: so kämpften Roms Gladiatoren. Mainz.

Kanz, F. and K. Grossschmidt. 2002. Gladiatoren in Ephesos: Tod am Nachmittag: Eine Ausstellung im Ephesos Museum Selçuk. Vienna.

Kanz, F. and K. Grossschmidt. 2006. “Head Injuries of Roman Gladiators.” Forensic Science International 160: 207–16.

Kanz, F. and K. Grossschmidt. 2009. “Dying in the Arena: The Osseous Evidence from Ephesian Gladiators.” In T. Wilmott, ed., 211–20.

Köhne, E., C. Ewigleben, and R. Jackson. 2000. Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Berkeley.

Landes, C., ed. 1990. Le cirque et les courses de chars, Rome-Byzance: Catalogue de l’exposition. Lattes.

Laurence, R. and J. Berry, eds. 1998. Cultural Identity in the Roman Empire. London.

Levick, B. 1983. “The Senatus Consultum from Larinum.” Journal of Roman Studies 73: 97–115.

Mahoney, A. 2001. Roman Sports and Spectacles: A Sourcebook. Newburyport, MA.

Meijer, F. 2010. Chariot Racing in the Roman Empire: Spectacles in Rome and Constantinople. Translated by L. Waters. Baltimore.

Nelis-Clément, J. and J.-M. Roddaz, eds. 2008. Le cirque romain et son image: Actes du colloque tenu à l’Institut Ausonius, Bordeaux, 2006. Pessac.

Petzl, G. and E. Schwertheim. 2006. Hadrian und die dionysischen Künstler: Drei in Alexandria Troas neugefundene Briefe des Kaisers an die Künstler-Vereinigung. Bonn.

Potter, D. 2010. “Entertainers in the Roman Empire.” In D. Potter and D. Mattingly, eds., 280–349.

Potter, D. and D. Mattingly, eds. 2010. Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor.

Robert, L. 1940. Les gladiateurs dans l’Orient grec. Paris.

Shelton, J.-A. 1998. As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History. 2nd ed. New York.

Tameanko, M. 1999. Monumental Coins: Buildings and Structures on Ancient Coinage. Iola, WI.

Teyssier, E. and B. Lopez. 2005. Gladiateurs: Des sources à l’expérimentation. Paris.

Wiedemann, T. 1992. Emperors and Gladiators. London.

Wilmott, T., ed. 2009. Roman Amphitheatres and Spectacula: A 21st-Century Perspective. Oxford.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

Two general sourcebooks of translated documents specifically on Roman sport and spectacle, including a representative selection of epitaphs, decrees, and graffiti, are Futrell 2006 and Mahoney 2001; see also the relevant sections of Shelton 1998.

For those interested in gladiator equipment, Junkelmann 2000 contains a useful catalog with color photographs (161–87) of surviving examples of gladiator armor, mostly helmets. Comprehensive published accounts of some of the recent attempts at reenactment are Teyssier and Lopez 2005 and Junkelmann 2000.

There are several collections of inscriptions (in the original languages) specifically related to gladiators: for the Greek East, the old but still indispensable reference is Robert 1940, and for the West, see now the four volumes of the Epigrafia anfiteatrale dell’occidente Roman (1988–96) by various editors. Other standard collections of inscriptions relevant to sport and spectacle are the CIL and the ILS. Within these multivolume sets, a concentration of inscriptions relating to the Roman circus and charioteers can be found in CIL 6.10047–79 and ILS 5277–316, while CIL 6.10083–161 and ILS 5181–210 deal with actors.

Enlightening discussions of how social values can be derived from the tombstones of gladiators include Hope 1998 and 2000 and Garraffoni 2008.

The classic works on chariot racing and circuses are Cameron 1976 and Humphrey 1986, while Meijer 2010 offers a reader-friendly, up-to-date summary of the subject. See also the specialized essays in Nelis-Clément and Roddaz 2008. Some examinations of the lively topic of circus curse tablets are Heintz 1998 and Gager 1990 and 1992.

A selection of color images of toys, lamps, and other material objects relating to Roman sport and spectacle are conveniently available in Köhne, Ewigleben, and Jackson 2000 and Jacobelli 2003, which also contains reproductions of many of the most famous gladiator graffiti.

On entertainment structures on coins, see Bergmann 2008; Elkins 2006; Tameanko 1999; and Desnier 1990.

The evidence from the gladiator cemetery at Ephesos is described by Kanz and Grossschmidt 2002, 2006, 2009, and in Curry 2008.