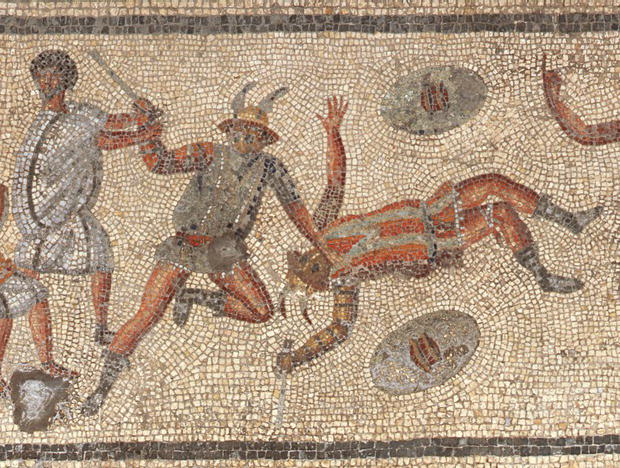

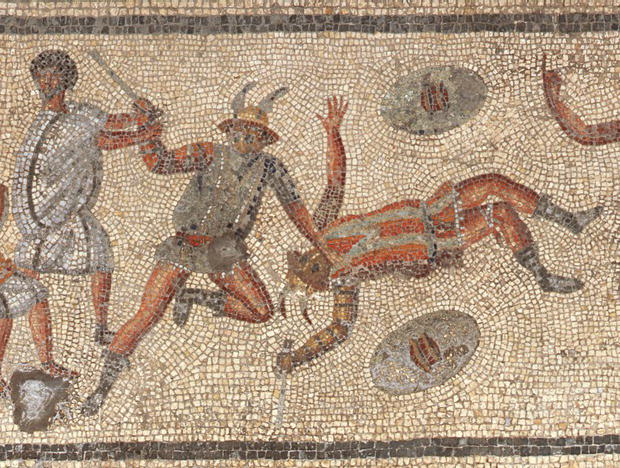

Figure 31.1 Mosaic from Zliten, Libya showing a fallen gladiator appealing for missio while a referee restrains his opponent, third century CE. Source: © Gilles Mermet/Art Resource, NY.

It is common for modern commentators to express puzzlement at the Romans’ ability to derive enjoyment from watching brutal arena spectacles, which, in their final form, included animal hunts, beast fights, public executions, and armed combat between trained professionals. The standard refrain is to emphasize how different moderns are from ancients in taking pleasure from such things. Thus Catharine Edwards in her excellent study Death in Ancient Rome writes, “It is hard for the modern reader not to be alienated by the idea that the sight of a man struggling against the pain of a fatal wound can constitute a source of edification and indeed visual joy” (Edwards 2007: 77). Her sentiments are echoed by Eckart Köhne: “Roman civilization and culture is never so utterly remote from our understanding as in the matter of these life-and-death games” (Köhne 2000: 12). We, it seems, are nothing like those debased spectators in their arena seats.

Armed with attitudes like this, earlier scholars have looked for the attractions of arena spectacles in various features of Roman culture and society, using anthropological, symbolic, or sociological analyses, so that gladiatorial combats have been interpreted as “liminoid rituals” that sought to curtail disorder by staging chaos under controlled conditions, as manifestations of elite Roman ideals about masculinity and proper comportment in the face of adversity, as moral parables that offered social rebirth to infames (those, like gladiators, who lacked good repute) through displays of virtus (“manliness”), as reminders to peacetime Romans of their proud martial heritage, or as symptoms of mass psychiatric dysfunction. Arguments along these lines, while often insightful and enlightening, confine the allure of watching gladiatorial combats to the specifics of the Roman context, and they interpose a comfortable (and comforting) distance between us and them.

I confess to finding this perplexity with the Romans’ devotion to their violent spectacles, well, perplexing, because it is hardly without parallel. In the first place, ancient gladiators reimagined for the modern age continue to exert a strong pull on contemporary consumers of mass media. A film such as Gladiator (2000) or a television series like Spartacus: Blood and Sand (2010), both commercial successes, are unflinching in their portrayal of arena violence. One might infer from this that modern audiences still find the idea of “a man struggling against the pain of a fatal wound” engaging and enthralling, even if in vivid facsimile rather than in stark reality.

Far more significantly, even if there are no exact parallels for the Roman games per se, the historical record is hardly lacking in instances of violent spectacle – whether punitive, ludic, or religious – staged before large and appreciative crowds. Public executions are an obvious example. In the Middle Ages, tournaments, events that featured high levels of frequently lethal violence, regularly attracted numerous spectators. In Early Modern Europe boxing, cudgeling, sword fighting, and brawling were immensely popular, as were bearbaiting and dogfighting. Even today, bullfighting and dogfighting retain their attraction for certain audiences. The fastest growing spectator sport among American males aged 18–34 is mixed martial arts, also known as ultimate fighting. This sport, essentially a revival of the Greek pankration, can be shockingly violent.

On a less brutal plane, contact sports such as American football or rugby draw enormous crowds. In such games, violence may not be the main point of the proceedings, but it is a prominent facet of what is going on. Spectators may appreciate the artistry of a good touchdown pass, but they appreciate just as much the intensity of a good hit. Indeed, that the most savage hits have been excised from their sporting context and then sold in DVD compilations (with titles like “Moment of Impact” or “The NFL’s Greatest Hits”) suggests that, for some, violence is the key attraction. The same is true of ice hockey fights, film of which is also sold in the form of stand-alone compilations.

Looked at from this perspective, the Roman fascination with their games appears considerably less alien than it might at first appear. I would go further and argue that whereas the form of arena games was unquestionably a product of the Roman historical and cultural context, the desire of the Romans to watch them was not. It speaks to something much deeper in the human psyche.

Students of modern sport have posited a variety of reasons why audiences watch and engage emotionally with sporting events. Many of their ideas apply directly or indirectly to arena spectacles and merit careful consideration. All the complexities of this field cannot possibly be covered here, but a sample may be offered to illustrate the main thrusts of analysis.

In the first place, contextual factors set sport apart as a special, and hence potentially appealing, activity in which normal behavioral rules do not apply (Huizinga 1950 (1938): 1–27). Sports nearly always take place in some venue specifically designed to house them, such as a lined playing field, roped-off boxing ring, or sunken cockfighting pit. The event is thus physically set aside from everyday experience. Rituals and rules attend the spectacle and umpires or observers are often on hand to see they are properly adhered to. Spectators are familiar with these rules and rituals, and they expect the proper protocols to be followed. Athletes often wear outfits specific to the occasion – for example, American football pads, or boxing shorts and shoes – and, where applicable, they use specialized equipment, such as sticks, rackets, gloves, or modified weapons. The combined effect of these features is to lend an air of theatricality and even artificiality to the proceedings.

These observations apply equally to violent sports and even to nonsporting violent spectacles such as public executions. The latter, too, were staged at specific locations – the gallows, scaffolds, or other traditional places of execution. They were hedged about by all sorts of rituals and rules that the spectators expected to be properly enacted, and performers often wore peculiar outfits (think of the executioner’s hood) and used specialized tools (the guillotine is perhaps the most infamous, but there are other examples, such as modified wagon wheels used for the vile procedure called “breaking on/with the wheel”). In this way, the entire event – whether a sporting game or a violent public ritual – was set apart as something out of the ordinary no matter how real and intense the violence of the spectacle might be. The context tells the spectator, “Here, the usual standards do not apply.”

To appreciate the determinative effect of these factors on how people interpret what they are watching, contemplate the different consequences of beating up an opponent in a fist fight on the street outside Madison Square Garden in New York City while wearing everyday clothes, and beating up that same opponent inside Madison Square Garden, in a roped-off canvas platform while wearing shorts and special shoes and gloves. The former would be cause for arrest, fines, or social opprobrium; the latter would bring a sporting title, a sizeable purse, and respect. The context in which sport (and violence) takes place helps to establish its acceptability and to lend it cultural meaning.

Another feature of sports themselves that makes them alluring for spectators is that they present competitors with hurdles that they must strive to overcome while adhering to a set of rules. Sports entail artificial rules (no touching a ball with one’s hands in soccer, for instance) that are designed to put obstacles in the way of the athletes’ success (Suits 1978: 20–42). Competitors face an opposition playing by the same rules and must display a high degree of skill, determination, and endurance to succeed. The knowledgeable spectator knows what to look for in appreciating the skills, training, and artistry of the athletes as they strive for success within the confines of the rules. Furthermore, part of what is alluring about watching sport is that the spectators are familiar with the rules and expect performers to abide by them and umpires or referees to enforce them. As we all know, spectators can become very upset if the rules are flouted without penalty, or if they are enforced in a way that is judged unfair.

That the outcome of the contest is uncertain is another key feature of sport. It is usually unclear in any given encounter what will transpire and how it will transpire. Each match or game has its own dynamics, and an upset victory by an “underdog” is always a possibility.

To be sure, researchers remain unclear about the psychological mechanisms that underlie the spectators’ emotional involvement in how a game plays out. Part of what is going on in watching sports live as a member of a crowd is what Durkheim dubbed “collective effervescence,” that sense of empowerment, connectedness, validation, and even euphoria people feel when sharing a mass event with like-minded fellow enthusiasts (Durkheim 2001 (1912): 154–68). Such feelings, of course, are not restricted to watching sports, and fans can get just as engaged when watching a contest alone on television. Various propositions – one hesitates to call them “theories” – have been advanced to explain this phenomenon (Fagan 2011: 197–209). One that can be called a theory, BIRGing (“Basking in Reflected Glory”), presumes that the self-esteem of spectators is raised by association with their favored athletes’ victories. Another proposition is that sport can be “representational” in the sense that spectators identify closely with athletes in the belief that the contestants represent key facets of the spectators’ group identity (such as race, nationality, city of residence, etc.). Others see the keys to sport’s allure in the escape from boredom or the pleasures of betting and making a profit. More recently a possible neurobiological basis for sport spectatorship has emerged with the discovery of mirror neurons in the brain. These cells fire the same way when an activity is observed as when it is performed. That is, when spectators are watching athletes, their brains may make them feel the same suspense, commitment, and drive for victory as the athletes themselves, though more research is required to confirm this possibility (Rizzalotti and Fabbri-Destro 2009; Rizzalotti and Sinigaglia 2008). In most of these approaches, either the process or the outcome of sport is seen as the key to the pleasure of watching.

The factors discussed above help make sport intensely engaging, and gladiatorial combats shared most or all of them, even if some scholars still insist that such combats lie outside the realm of sport proper (Poliakoff 1987: 7; Horsmann 2001). However, our focus here is not on issues of definition but on what brought people to watch. If gladiatorial combats appealed to spectators for many of the same reasons that sport does, then we shall have gained a very different perspective on what was going on in the arena’s stands than that advanced in most studies of the phenomenon. Let us review those factors, beginning with contextual ones, with gladiatorial combats in mind.

Gladiatorial games took place in their own space, one fashioned to meet their specific requirements. The fights were held in amphitheaters, a type of building specifically designed for that purpose. Games could also be held in circuses (designed primarily for chariot racing), or stadia (used for athletic contests), or even in temporary installations set up in the forums of Roman cities (see, for example, Livy 44.18.8; Scriptores Historiae Augustae Hadrian 19.3; Vitruvius On Architecture 5.1.1). Nonamphitheatral settings, such as theaters or stadia in the Greek East, were often modified to accommodate gladiatorial spectacles (Welch 1999; see also Chapter 38 in this volume).

Above and beyond the spaces in which they took place, gladiatorial combats themselves were replete with elements that clearly separated them from everyday experience. The spectacle opened with a procession, the pompa, in which the sponsor, prizes, equipment, and combatants paraded in front of the spectators (Tertullian On Spectacles 7.2–3; [Quintilian] Major Declamations 9.6; CIL 4.3883, 4.7993). The procession announced the official start of the spectacle, separating it from the everyday in time, just as the physical context did in space. It also gave the audience a chance to see the physical form of the men before they fought and may have aided betting. The fights appear to have begun with a blast of horns and they progressed to musical accompaniment. The gladiators wore often outlandish outfits and wielded specially designed weapons that only loosely corresponded to the sort of equipment used by actual warriors on real battlefields (Coulston 1998). Examples include the nets, tridents, and shoulder fittings (galeri) of the retiarii; the wide-brimmed helmets, thigh-high leg padding, and bent swords of the Thraeces; the visored helmets and arm padding (manicae) of the secutores; and, among the strangest of all, the crescent-bladed arm cuff of the scissores (or arbelai).

Gladiatorial combats presented obvious hurdles for the participants and were conducted in accordance with established rules. The details of those rules, called the lex pugnandi, evade us, but they must have dictated what sorts of moves were allowed, or more likely, which ones were disallowed (Carter 2006/7). As depicted in numerous arena scenes in Roman art, umpires were on hand to enforce these rules (Figure 31.1 and Figure 31.2). We know from inscriptions that gladiators trained to fight with specific combinations of arms and armor and so in specific styles that probably entailed familiar combinations of thrusts, parries, dodges, and dives to achieve victory (see, for example, CIL 6.4333 = ILS 5116 or CIL 6.10192 = ILS 5091). This is probably why particular kinds of fighters had their own followers, though we only hear of two – the parmularii who supported the Thraeces, and the scutarii who favored murmillones (Dunkle 2008: 106–7). Arena spectators were thus in a position to appreciate the skill, determination, and endurance of individual gladiators. That arena spectators were familiar with gladiatorial combat moves is revealed by casual comments in ancient literary sources that show that spectators easily recognized lackluster performances (described as “fighting by the book,” ad dictata pugnavit, in Petronius Satyricon 45.12).

Figure 31.1 Mosaic from Zliten, Libya showing a fallen gladiator appealing for missio while a referee restrains his opponent, third century CE. Source: © Gilles Mermet/Art Resource, NY.

Figure 31.2 Mosaic from Zliten, Libya showing an injured gladiator (having dropped his shield and raised his index finger) appealing for missio, third century CE. Source: © Gilles Mermet/Art Resource, NY.

The uncertainty of the outcome of gladiatorial combats was a major part of their allure. This is reflected in the facts that the skill level of individual gladiators was carefully graded based on the number of fights they had survived and that concerted efforts were made to match gladiators of similar skill levels (Potter 2010: 341–5). This was obviously meant to help ensure that combats did not consist of a grossly overmatched fighter being helplessly slaughtered but rather presented dramatic fights between evenly matched opponents.

Gladiatorial combats were thus not the mindless butchery habitually depicted in Hollywood recreations, or the artless flailing about of men desperate to save their own skins. They appealed to audiences in large part because they were carefully thought-out contests that demanded skill and training. Gladiatorial graffiti are particularly instructive in this regard because they were etched or painted by the spectators themselves, who thus tell us directly the sorts of things they were looking for in a fight (Langner 2001; Jacobelli 2003: 39–42). Typical examples report outcomes, such as “Priscus, of the Neronian school, six fights, won; Herennius, freeborn [or freed], 18 fights, died,” (CIL 4.1422), or accomplishments, for example, “Albanus, left-hander, freeborn [or freed], 19 fights, won” (CIL 4.8056; Coleman 1996).1 What these fans express is a concern for the status, training pedigree, and fight record of each combatant, not to mention an appreciation for the details of fighting style, such as left-handedness. This indicates that the spectators came to watch less out of raw bloodlust, as is often assumed, and more out of a desire to see exciting contests fought with style by trained experts.

Evidence left behind by the experts themselves buttresses these inferences. Epitaphs of gladiators are marked by a discernible pride in the very same categories as those prized by the spectators in their graffiti. These epitaphs identify the status and style of fighting of the deceased and record what we might term their “career stats.” Consider this epitaph, from a gravestone found in Sicily: “Flamma, secutor. He lived 30 years. He fought 34 times, won 21 times, drew 9 times, and was spared 4 times. Syrian by birth. Delicatus made [this tomb] for a worthy comrade-at-arms” (CIL 10.7297 = ILS 5113). The inclusion in career records like this of instances where the gladiator lost the bout but was spared (the term used is “sent,” missus) offers evidence of pride in performance; despite losing, he was deemed to have fought well enough to earn release on appeal. The commemorator, after all, could have just passed over those instances in silence or fudged the numbers. (On the mechanics of gladiatorial combats, see Chapter 25.) The epitaphs, then, self-identify the gladiators as a cadre of professional elite fighters who played to their public and, despite the risks, reaped substantial rewards for doing so (Hope 2000).

Gladiatorial combats, like many sports, also involved a great deal of overt showmanship. They were, in other words, constructed as spectacles, the attraction of which extended far beyond simple bloodshed. Some indication of this showmanship can be detected in images of gladiatorial fights. A famous mosaic from Zliten in Libya shows various phases of an arena spectacle. In one scene (Figure 31.1) a fallen gladiator appeals to the sponsor while his opponent has to be physically restrained from killing him by an umpire. It may be that the victor’s blood was up and he had lost track of himself – or it may be that he was putting on a good show. In another scene (Figure 31.2) an injured murmillo, bleeding profusely from his left thigh, turns away from the fight and appeals by raising his finger while the umpire marks a pause in the fight by stretching his rod across his back. The stance adopted by the waiting winner, a hoplomachus, is precisely the pose used for statues of gods and generals and is pure showmanship.

While these suggestions may be subjective interpretations of ambiguous images, clearer indications of showmanship are provided by the elaborate equipment used by gladiators, especially their heavily decorated helmets and shields. The professional fighters also used stage names, which tended to be evocative, sexy, or ironic: Ferox (“Fierce”), Iaculator (“[Net?] Thrower”), Mucro (“Blade”), Pugnax (“Fightlover”), Scorpio (“Stinger”), Velox (“Quick”), Cupido, Eros (both “Lust”), Pulcher (“Pretty Boy”), Clemens (“Merciful”), Columbus (“The Dove”), Cycnus (“The Swan”), Murranus (“Perfume Boy”), or Hilarus (“The Joker”) (Junkelmann 2008: 267–8; Ville 1981: 306–10).

We can conclude from all this that there were features of gladiatorial combat, many of them shared with other forms of sport and violent spectacle staged in different times and places, that made attendance an alluring prospect. The deeper question is: why do people like to watch violence as entertainment?

The numerous similarities between sport and arena spectacles offer important insight into the appeal of gladiatorial combats, but it nonetheless remains true that the public entertainments on offer in Rome were unusually, though by no means uniquely, violent. It is, therefore, important to give due consideration to the question of why watching violence was, and continues to be, popular.

The matter of why people watch violence as a diversion has attracted far less attention than it deserves since the focus has been overwhelmingly on the impact of violence in entertainment rather than on the reasons for its enduring allure (e.g., Grimes, Anderson, and Bergen 2008; Haugen 2007). The most comprehensive psychological theory to explain the attraction of violent entertainment is that of “affective dispositions,” proposed by Dolf Zillmann and his various collaborators over the past three decades or so.

“Affective dispositions” describe the attitude of spectators toward the performers they are watching. Dispositions can be positive or negative. When good things happen to a liked agent, spectators respond with pleasure (or “euphoria,” in psychological terminology), when bad things, with distress (“dysphoria”). The inverse is also true; if an agent is disliked, spectators react euphorically when bad things happen to that agent and dysphorically when good things happen to him or her.

Two features of affective dispositions warrant emphasis. First, spectators are aware of their role as witnesses. They identify with agents to a high degree, but they also know that the agents are not actually their friends or enemies and relate to them in what are termed “parasocial relations,” which impel an audience to root for or against characters as if they were real friends or enemies. Second, a process of “moral monitoring” is constantly at work in that spectators form their attitudes about agents (their “affective dispositional alignments”) on the basis of moral assessments and then anticipate outcomes in terms of deserts. Some characters become liked by doing things judged good and are felt to “deserve” their rewards, whereas other characters are disliked because they do bad things and so deserve any misfortune that befalls them.

In dramatic contexts affective dispositions are generated through narrative structure and character development. In violent narratives, dislike of a character allows viewers to take pleasure in violence when they consider it justified. This attitude is usually brought about by dwelling on the horrific and unjustified violence of a villain prior to the hero meting out often no less horrific but justified violence to that villain. It is not the violent actions themselves that elicit enjoyment or disgust but rather who is doing what to whom and for what reason. The attitude of the viewer toward both the perpetrator and the victim converts these considerations into moral assessments of the violence as either monstrous or magnificent (Zillmann 1998, 2000).

So much for the role of affective dispositions in audience appreciation of fictional and dramatic narratives. What has this got to do with real violence done to real people as in gladiatorial combat? It has been found that affective dispositions do not distinguish between fictional and factual realms. The same mental mechanisms of disposition formation as those charted for fiction have been shown to be at work when people watch, say, the news. They empathize with agents they are positively disposed toward and feel satisfied by the sufferings and setbacks of those they dislike. Since people in the news are generally already known to the viewer, narrative structure and character development are not necessary for affective dispositions to form. Rather, viewers’ attitudes are “predeveloped” from a general knowledge of the wider context (Zillmann and Knobloch 2001).

Although the attitude of Roman spectators toward arena performers can only be surmised from scattered scraps of evidence, the character of the arena context prompts some general suggestions. To begin with, given that gladiators were generally low-status individuals, and given the announcement of an event’s details in advance, it is reasonable to assume that spectator attitudes were largely predeveloped and tended to the negative. It is also likely that the crowd’s attitudes varied with the phases of the spectacle. Even a cursory review of arena personnel is enough to make this probable since they included animals, professional huntsmen, helpless execution victims, forced mass combatants, trained and professional gladiators, volunteer fighters, and occasionally also athletes and mock fighters. It is highly unlikely, on the face of it, that the crowd adopted a uniform emotional orientation toward all of these performers and victims. Rather, their attitudes shifted in response to developments on the sand – and that in itself would make attendance at arena spectacles a dynamic and exciting psychological experience.

As to the gladiators in particular, it is not obvious how spectator attitudes formed and operated as they watched since our evidence is so patchy. As far as we can tell, gladiators did not adopt the flamboyant “good guy/bad guy” personae of, say, modern professional wrestlers, whose moral virtues and failings (and ongoing vendettas) generate dramatic narratives around which spectator attitudes can readily form. As we have just seen, however, gladiatorial epitaphs and graffiti, as well as surviving advertisements for spectacles, identify the gladiator, his style of fighting, his status or training school, and his fight record to date – all details that clearly mattered to the arena fan. Might it be that they helped establish ongoing narratives that predeveloped spectator attitudes for or against individual gladiators?

In the case of M. Attilius, a particularly dramatic narrative is revealed in a series of graffiti about him etched into the wall of a tomb outside the Nucerian Gate at Pompeii.

The first text reads: “M. Attilius, beginner, won; Hilarus, of the Neronian school, 14 fights, 12 crowns, spared” (CIL 4.10238). Attilius was a freeborn (or freedman) volunteer fighter (auctoratus), as his name and lack of training school affiliation demonstrate. He was a newcomer (tiro) who, in his very first fight, went up against the professionally trained Hilarus, a veteran of 14 fights with 13 wins under his belt – an apparent gross mismatch. Yet Attilius won in an upset victory. That Hilarus was “sent” (missus) tells us that both men put on a good show. Attilius’s next appearance was no less dramatic: “M. Attilius, one fight, one crown, won; L. Raecius Felix, 12 fights, 12 crowns, spared” (CIL 4.10236). This bout pitched Attilius against a free volunteer gladiator like himself, but this time an unbeaten veteran of 12 fights. Yet again, despite the apparent mismatch, Attilius emerged victorious, and again his defeated opponent was spared – another good fight with an upset at the end. It does not take much to imagine how exciting Attilius’s explosive debut on the local arena circuit must have been. That the graffitist diligently updated Attilius’s fight record for the second bout shows that Attilius’s performance was being carefully tracked, as was that of his opponents. These details may have built dramatic narratives of sorts around each gladiator.

We can only make suggestions as to how dispositions functioned at the Roman arena since the details remain elusive and we cannot poll the spectators or observe them in their seats. A recent analysis of the emotional dynamics inherent in violent encounters may help to fill out the picture. This model, developed by the sociologist Randall Collins (2008), suggests that an emotional field of tension and fear imbues all confrontations. Violence may then be defined as a set of pathways around confrontational tension and fear, in that it can only occur once these emotional barriers have been overcome. When real violence does occur, most people prove incompetent at it, flailing about ineffectually in face-to-face fights or firing their weapons wildly in combat. The incompetence is generated by unresolved tension and fear, which is why most fights are as much about bravado and bluster as they are about inflicting genuine harm.

The two chief means for reducing confrontational tension/fear are, first, attacking the weak, and, second, setting boundaries on how the violence plays out by, for instance, establishing rules for staged fights. Trained fighters, who mutually agree to the rules, can then engage in high levels of violence within the confines of those rules. Furthermore, in most societies trained fighters are admired as an elite caste – think of the instant respect accorded a person who identifies themselves as a black belt in the martial arts. This is especially the case among those who turn out to watch them perform. Indeed, the presence of an enthusiastic audience has a demonstrable effect on prolonging and intensifying staged fights as the combatants and the spectators are emotionally synchronized (what Collins terms “mutually entrained”) in that they all share knowledge of the rules and protocols of the fight. The more enthusiastic and supportive the spectators, the more competent, intense, and prolonged the fight tends to be.

The mutual emotional “entrainment” of the spectators with the fighters implies important consequences for the experience of watching gladiatorial combats. In gladiatorial combats, as we have seen, the crowd was familiar with the rules and with the moves of the fighters. Gladiators, despite their social debasement, were widely admired by their fans as a breed apart (although that admiration was always contingent upon performance). The more aggressively the gladiators fought, the more the audience would encourage them, which would itself prolong the fight and increase the level of aggression on display. Gladiators knew that they had to put on a show of fighting skill to meet the crowd’s approval; doing so was literally a matter of life and death and, if their epitaphs are any indication, also of pride among their peers. Gladiator and spectator were thus partners in the arena’s dance of violence, each playing a role in its lethal choreography.

It seems likely, then, that in addition to the sportlike features of gladiatorial combats already reviewed, a large part of the enjoyment and thrill of watching gladiatorial bouts rested in the spectators’ disposition for or against particular fighters or types of fighter set against the overall emotional synchrony between performer and audience established by everyone’s knowledge of the rules governing the fights and the quality of the combat moves used to achieve victory.

We may conclude from all this that there were lures of the arena that stood outside the specific cultural context of ancient Rome; lures that can be documented from quite divergent historical environments. The Roman fascination with gladiatorial combat is therefore hardly “incomprehensible” or “alienating.” Watching it was a dynamic psychological and emotional experience akin to watching sport, particularly combat sports. Gladiatorial bouts shared features with most types of sporting action. Spectators got behind particular fighters, felt emotionally synchronized with both the performers and the rest of the audience, and became engaged in the action as the fighters struggled within the confines of a known set of rules to achieve victory. They watched because they were like us, not because we are unlike them.2

ABBREVIATIONS

CIL: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

ILS: Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae

NOTES

1 All translations of ancient texts are my own.

2 An important caveat: in stating this, I am not making a reductionist claim that ancient spectators and modern sports fans are alike in every respect, let alone that their experience of spectatorship was identical. Matters of historical and cultural context, the meaning(s) they assign to what they watch, and the broad divergences in social experience and cultural values ensure that there are important differences between each case. The underlying mental mechanics involved in watching sport, however, are likely to be constant since ancients and moderns share the same brain physiology and the mental architecture that it generates.

REFERENCES

Abbott, G. 2006. Execution: The Guillotine, the Pendulum, the Thousand Cuts, the Spanish Donkey, and 66 Other Ways of Putting Someone to Death. New York.

Balsdon, J. P. V. D. 1969. Life and Leisure in Ancient Rome. New York.

Barker, J. 1986. The Tournament in England, 1100–1400. Suffolk, UK.

Barton, C. 1993. The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster. Princeton.

Bastien, P. 2006. L’exécution publique à Paris au XVIIIe siècle: Une histoire des rituels judiciaires. Seyssel.

Bellen, H. and H. Heinen, eds. 2001. Fünfzig Jahre Forschungen zur antiken Sklaverei an der Mainzer Akademie 1950–2000. Mainz.

Bergmann, B. and C. Kondoleon, eds. 1999. The Art of Ancient Spectacle. New Haven.

Berntson, G. and J. Cacioppo, eds. 2009. Handbook of Neuroscience for the Behavioral Sciences. 2 vols. Hoboken.

Bomgardner, D. 2000. The Story of the Roman Amphitheatre. London.

Bondebjerg, I., ed. 2000. Moving Images, Culture, and the Mind. Luton, UK.

Carter, J. 1981. Ludi Medi Aevi: Studies in the History of Medieval Sport. Manhattan, KS.

Carter, M. 2006/7. “Gladiatoral Combat: The Rules of Engagement.” The Classical Journal 102: 97–114.

Chapman, A. and H. Foot, eds. 1976. Humour and Laughter: Theory, Research, and Applications. London.

Coleman, K. 1996. “A Left-Handed Gladiator at Pompeii.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 114: 194–6.

Collins, R. 2008. Violence: A Micro-Sociological Theory. Princeton.

Cooley, A., ed. 2000. The Epigraphic Landscape of Roman Italy. London.

Coulston, J. 1998. “Gladiators and Soldiers: Personnel and Equipment in ludus and castra.” Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies 9: 1–17.

Dunkle, R. 2008. Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Harlow, UK.

Durkheim, É. 2001 (1912). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by C. Cosman. Oxford.

Edwards, C. 2007. Death in Ancient Rome. New Haven.

Evans, R. 1996. Rituals of Retribution: Capital Punishment in Germany, 1600–1987. Oxford.

Fagan, G. 2011. The Lure of the Arena: Social Psychology and the Crowd at the Roman Games. Cambridge.

Flori, J. 1998. Chevaliers et chevalerie au Moyen Age. Paris.

Futrell, A. 2006. The Roman Games: A Sourcebook. Malden, MA.

Goldstein, J. 1989. Sports, Games, and Play: Social and Psychological Viewpoints. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ.

Goldstein, J. 1998. Why We Watch: The Attractions of Violent Entertainment. New York.

Golvin, J.-C. 1988. L’Amphithéâtre romain: Essai sur la théorisation de sa forme et de ses fonctions. 2 vols. Paris.

Grimes, T., J. Anderson, and L. Bergen. 2008. Media Violence and Aggression: Science and Ideology. Thousand Oaks, CA.

Guttmann, A. 1986. Sports Spectators. New York.

Guttmann, A. 2004. Sports: The First Five Millennia. Amherst.

Hardy, S. 1974. “The Medieval Tournament.” Journal of Sport History 1: 91–105.

Haugen, D., ed. 2007. Is Media Violence a Problem? Detroit.

Hope, V. 2000b. “Fighting for Identity: The Funerary Commemoration of Italian Gladiators.” In A. Cooley, ed., 93–113.

Hopkins, K. 1983. Death and Renewal. Cambridge.

Horsmann, G. 2001. “Sklavendienst, Strafvollzug oder Sport? Überlegungen zum Charakter der römischen Gladiatur.” In H. Bellen and H. Heinen, eds., 225–41.

Huizinga, J. 1950 (1938). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. New York.

Jacobelli, L. 2003. Gladiators at Pompeii. Rome.

Junkelmann, M. 2000. “Familia Gladiatoria: The Heroes of the Amphitheatre.” In E. Köhne, C. Ewigleben, and R. Jackson, eds., 31–74.

Junkelmann, M. 2008. Gladiatoren: Das Spiel mit dem Tod. Mainz.

Keen, M. 1984. Chivalry. New Haven.

Köhne, E. 2000. “Bread and Circuses: The Politics of Entertainment.” In E. Köhne, C. Ewigleben, and R. Jackson, eds., 8–30.

Köhne, E., C. Ewigleben, and R. Jackson, eds. 2000. Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Berkeley.

Kyle, D. 1998. Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome. London.

Kyle, D. 2007. Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, MA.

Langner, M. 2001. Antike Graffitizeichnungen: Motive, Gestaltung und Bedeutung. Wiesbaden.

Malcolmson, R. 1973. Popular Recreations in English Society, 1700–1850. Cambridge.

Merback, M. 1999. The Thief, the Cross, and the Wheel: Pain and the Spectacle of Punishment in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. Chicago.

Mitchell, T. 1991. Blood Sport: A Social History of Spanish Bullfighting. Philadelphia.

Plass, P. 1995. The Game of Death in Ancient Rome: Arena Sport and Political Suicide. Madison.

Poliakoff, M. 1987. Combat Sports in the Ancient World. New Haven.

Potter, D. 2010. “Entertainers in the Roman Empire.” In D. Potter and D. Mattingly, eds., 280–349.

Potter, D. and D. Mattingly, eds. 2010. Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor.

Rizzalotti, G. and M. Fabbri-Destro. 2009. “The Mirror Neuron System.” In G. Berntson and J. Cacioppo, eds. 1, 337–57.

Rizzolatti, G. and C. Sinigaglia. 2008. Mirrors in the Brain: How Our Minds Share Actions, Emotions, and Experience. Translated by F. Anderson. Oxford.

Russell, G. 1993. The Social Psychology of Sport. New York.

Shubert, A. 1999. Death and Money in the Afternoon: A History of the Spanish Bullfight. New York.

Suits, B. 1978. The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia. Toronto.

Toner, J. P. 1995. Leisure and Ancient Rome. Cambridge.

van Dülmen, R. 1990. Theatre of Horror: Crime and Punishment in Early Modern Germany. Cambridge.

Ville, G. 1981. La gladiature en Occident, des origines à la mort de Domitien. Rome.

Wann, D., M. Melnick, G. Russell, et al., eds. 2001. Sport Fans: The Psychology and Social Impact of Spectators. New York.

Welch, K. 1999. “Negotiating Roman Spectacle Architecture in the Greek World: Athens and Corinth.” In B. Bergmann and C. Kondoleon, eds., 125–45.

Welch, K. 2007. The Roman Amphitheatre: From Its Origins to the Colosseum. Cambridge.

Wiedemann, T. 1992. Emperors and Gladiators. London.

Winkler, M. 2004. Gladiator: Film and History. Malden, MA.

Wistrand, M. 1992. Entertainment and Violence in Ancient Rome: The Attitudes of Roman Writers of the First Century a.d. Göteburg, Sweden.

Zillmann, D. 1998. “The Psychology of the Appeal of Portrayals of Violence.” In J. Goldstein, ed., 179–211.

Zillmann, D. 2000. “Basal Morality in Drama Appreciation.” In I. Bondebjerg, ed., 53–63.

Zillmann, D. and J. Cantor. 1976. “A Disposition Theory of Humour and Mirth.” In A. Chapman and H. Foot, eds., 93–115.

Zillmann, D. and S. Knobloch. 2001. “Emotional Reactions to Narratives about the Fortunes of Personae in the News Theater.” Poetics 29: 189–206.

Zillmann, D. and P. Vorderer, eds. 2000. Media Entertainment: The Psychology of its Appeal. Mahwah, NJ.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

The arguments articulated in this essay are based on those presented more fully in my book (Fagan 2011). Stimulating surveys and interpretations of Roman arena games are to be found in Barton 1993: 3–81; Hopkins 1983: 1–30; Kyle 1998 and 2007: 251–339; Plass 1995: 3–77; Potter 2010; Toner 1995: 34–52; Ville 1981; and Wiedemann 1992: 1–101. Still worth reading is Balsdon 1969: 288–313. Closely researched reconstructions of Roman gladiatorial armatures are to be found in Junkelmann 2008 (with plenty of color photographs). Ancient sources, including graffiti, are handily collected in translation in Futrell 2006, and original texts of relevant inscriptions can be traced in the pages of CIL, or in ILS 5083–162, or in the seven volumes (and counting) of Epigrafia anfiteatrale dell’occidente Romano (usually abbreviated EAOR).

For gladiators in modern culture, see Winkler 2004. A useful survey of ancient attitudes toward violent entertainments as expressed by early imperial authors is provided by Wistrand 1992.

On public executions, see Abbott 2006; Bastien 1996; Evans 1996; Merback 1999; van Dülmen 1990. On the Medieval tournament, see Barker 1986; Carter 1981; Flori 1998; Hardy 1974; and Keen 1984. Early Modern combat sports are described in Guttmann 1986: 53–82; Guttmann 2004: 52–76; and Malcolmson 1973: 42–51. On bullfights, see Mitchell 1991 and Shubert 1999.

Theories about the allure of sport are offered by Guttmann 1986: 175–85; Goldstein 1989; Russell 1993; and Wann, Melnick, Russell, et al. 2001.

Studies of Roman amphitheaters, and the seating dispositions within them, can be found in Bomgardner 2000; Golvin 1988; and Welch 2007. On gladiatorial armatures, see Junkelmann 2000 and 2008: 43–128.

For the psychology of spectatorship, especially affective dispositions and their functioning in watching violent entertainment, see Zillmann 1998, 2000; Zillmann and Cantor 1976; Zillmann and Vorderer 2000. Collins’s fascinating study of the dynamics built into violent encounters (Collins 2008) makes for enlightening reading.