Figure 33.1 Bronze statuette of an African child charioteer (discovered in Altrier), second century CE. Source: Musée national d’histoire et d’art Luxembourg, inv. n. 2004–15/1750, © MHNA Luxembourg/T. Lucas.

Our story begins sometime in the first century CE1 at one of the cemeteries on the outskirts of imperial Rome. There a group of mourners gathers around the funeral pyre of a charioteer for the Red team, which, together with the White, Blue, and Green teams, comprise the chariot racing industry at Rome. Shortly before, the Red team’s now-deceased charioteer, Felix (“Lucky”), having apparently run out of his namesake luck, met his end in a thunderous crash on the circus racetrack. While not the most famous charioteer of his day, Felix nonetheless inspired deep fanaticism even in death, for just as his funeral pyre reaches its peak temperature, Felix’s flesh disintegrating into ash, a distraught fan leaps onto the pyre, immolating himself together with his beloved charioteer. This intense display of devotion so threatens partisans of the other factions that they “spin” the incident as an accident: surely the man had fainted from the heat and incense, they claim, and accidentally fallen onto the pyre. The story is of particular interest to us here for two reasons: First, on an anecdotal level, its reporter (Pliny the Elder) claims to have read it in the acta diurna or the “daily acts” (Natural History 7.168). This suggests that sports news may have been an occasional or even regular feature of Rome’s daily gazette (see Baldwin 1979). Second, and more importantly, it points to the intensity of fans’ feelings toward the sport of chariot racing, its factions, and its heroes.

The fact that this story – probably the most extreme example of fan behavior to come down to us from the annals of imperial Rome – originates from the world of the circus will probably strike most readers as surprising. For among the many misperceptions about ancient Roman games that have become widespread, especially as a result of popular film and television, is the belief that gladiatorial combats were the premiere spectacle at Rome. For instance, it is often supposed that they attracted the biggest audiences or the most partisan fans. In fact, neither assumption is true. The Circus Maximus was many centuries older and considerably larger than the Colosseum (on such facilities, see Chapter 38 in this volume), and chariot races drew the largest crowds in Rome and throughout the Roman Empire and continued to do so centuries after the gladiatorial games faded away (see Chapter 43). Furthermore, there is no evidence for spectators in arenas behaving as fanatically as those in circuses or even theaters (Fagan 2011: 93 n. 34, 221). The reasons behind this are complex and go beyond the scope of this essay (but see further Chapter 31). Instead, the aim here is to explore circus games’ activity and setting, their star performers, their spectators and fans, and the importance of the circus games for Roman society as a whole.

Roman culture was a performance culture, and the Circus Maximus was its grandest stage. No larger man-made structure existed in the entirety of the Roman Empire, and no other building accommodated an audience on its scale (approximately a hundred and fifty thousand). In its fully developed form, the Circus Maximus became a showpiece for Rome’s hallowed traditions, urban splendor, and global ambitions – “a fitting place for a nation that has conquered the world” (Pliny the Younger Panegyric 51) – as well as the prototype for dozens of similar edifices around the Mediterranean. And, unlike any other form of spectacle building, the Circus Maximus, as the site of the rape of the Sabines, was intertwined with the legendary foundation of Rome itself. (For further discussion of the quasi-legendary rape of the Sabines, see Chapter 27.)

The Circus Maximus and circuses generally are most accurately thought of as sites of performance because of the different functions they served and the diverse programs that were staged in them. Some circus games (ludi circenses) were held annually as celebrations of festivals central to state religion (ludi publici), including the ludi Romani, ludi Apollinares, ludi Ceriales, ludi Megalenses, and ludi Florales. (On ludi in general, see Chapter 25.) Other games (ludi votivi) were held in association with major state events, such as military triumphs, temple dedications, emperors’ birthdays and funerals, and government jubilees. The games held in the circus included chariot races as well as other types of spectacles such as gladiatorial combats, animal hunts, public executions, mock battles, and paramilitary parades.

Chariot races were both the oldest and most popular of the spectacles. Their origins and development remain subject to debate; Etruscan and Italic influences are rightfully attributed a greater role than Greek in the most recent scholarship. The earliest chariot races at Rome are said to have taken place in the Vallis Murcia (the depression between the Palatine and Aventine hills) at Rome’s founding, in the context of religious ritual (Cicero Republic 2.12). The races were always suffused with ritual and custom, from the opening procession of gilded statues of the gods (pompa circensis) to the altars, shrines, and statues of deities installed along the track’s central barrier (euripus, commonly but less accurately called the spina) and the temples located within the circus stands. The religious aura of the circus was experienced in still other ways; poets and polemicists explored the idea of the racetrack as a temple and cosmos (Tertullian On Spectacles 8, Cassiodorus Variae 3.51), while astrologers and fortune tellers peddled hopes and dreams to passersby keen to alter their fate – or even just the outcome of a race (Cicero On Divination 1.132, Horace Satires 1.6.111).

The scale and appeal of the games expanded over the course of the Republic (509–31 BCE) and Empire (31 BCE–476 CE) so that they and their venues also evolved into vehicles of imperial ideology and mass entertainment. The games became an arena for political negotiation in which the people petitioned the emperor (e.g., for tax relief, Josephus Jewish Antiquities 19.24–7); an instrument of socialization through a public dress code and seating hierarchy (e.g., Suetonius Augustus 44.2, Calpurnius Siculus Eclogues 7); an advertisement for imperial munificence through the provision of jaw-dropping spectacles and state-of-the-art amenities (e.g., ILS 286, the dedicatory inscription thanking Trajan for his generosity in expanding the seating in the Circus Maximus); and a megaphone for Rome’s military muscle and superpower greatness through both temporary and permanent exhibitions of exotic captive cultures (e.g., displays of wild animals in triumphs, the dedication of an Egyptian obelisk along the euripus). Moreover, with the decline of gladiatorial games starting in the fourth century, chariot races gained even more popularity, particularly in the eastern part of the Roman Empire.

The races were preceded by a sacred procession that paraded through the city streets and terminated in the Circus Maximus, where it circled the track (Ovid Amores 3.2.43–58). The procession included images of the gods (the 12 Olympians and many others) that were conveyed to the monumental imperial skybox (pulvinar), which served as their shrine and house, from where they presided over the games in the company of the emperor. Following the gods in the procession were magistrates, young nobles, chariot drivers, athletes, dancers, musicians, incense burners, and temple attendants (Dionysius of Halicarnassos Roman Antiquities 7.70–3).

Once the parade was finished and the statues of the gods placed in the pulvinar, the crowd’s attention shifted to the 12 starting gates (carceres), where the teams of two- or four-horse chariots sat ready having been assigned their places by lot (see Figure 25.1 for a reconstruction showing the starting gates in the Circus Maximus). The game sponsor (editor spectaculorum), ensconced in a loggia above the starting gates, then dropped a white handkerchief (mappa) onto the track as a preparatory sign, which was probably followed by a further short brief signal (visual or vocal). The gates were then unlocked (probably simultaneously by a springing mechanism) and the teams exploded forward. The first stage of the race, which extended from the carceres to the white break line (alba linea) between the lower, conical turning post (meta secunda) and the right-hand wall of the stadium seating, allowed chariots to accelerate into position (Cassiodorus Variae 3.51). In the second stage the course narrowed, and the chariots raced in parallel lanes from the break line to the line before the judges’ tribunal. From this point onward the teams were free to cross lanes. The audience monitored the progress of the race by checking the lap-counting devices (one of seven eggs, the other seven dolphins) installed at either end of the euripus. The intrinsic thrill of beholding the race was further enhanced visually by other features, such as the sprinkling of selenite (a transparent form of gypsum) all over the arena floor so that it sparkled in the sun.

During the race the charioteers veered as close as possible to the central barrier to shorten their paths. They also listened to the shouts of advice from their team’s auxiliary rider on horseback (hortator) and strategized how to gain or guarantee a lead while they avoided the threats of the hairpin turns or too-close competitors (Silius Italicus Punica 303–456; Sidonius Apollinaris To Consentius 23.320–425). Using lightweight chariots built for speed, the teams raced counterclockwise and circled the euripus seven times (approximately 5 kilometers) in about 8–9 minutes total at an average speed of roughly 35 kilometers per hour (though speeds as high as 75 kilometers per hour may have been achieved in the straightaways). This gave attendants only about a minute to clear away any victims and wreckage from accidents, which were routine and occurred especially near the turning posts. The fact that crash scenes appear in the vast majority of visual representations suggests that such “shipwrecks” (naufragia) were not only frequent but also held widespread appeal to the spectators. The race concluded with the sound of a trumpet as the victorious charioteer crossed the finish line, which was located two-thirds of the way down the right side of the track and parallel to the pulvinar (on the left) and the judges’ tribunal (on the right). The victor ascended to the judges’ box to claim his prizes (palm branch, wreath, and money) and performed a victory lap in celebration.

Because there were regularly 24 such races on a game day (among other events) and some 66 days of games in a calendar year (as recorded for fourth-century Rome), they required the support of a complex infrastructure. The enormous burden of their cost and organization fell upon the four racing teams ( factiones) that served as contractors (Cameron 1976). Factiones were business entities that are attested from at least the first century BCE (but were surely in place centuries before). The stables (stabula factionum) sat about 1–2 kilometers away, in the Campus Martius, from which the animals, performers, and staff traveled to the Circus Maximus. From their earliest mention, the faction managers (domini) were private entrepreneurs who were members of a relatively elevated social class (the equestrians). Starting in the late third century, however, each faction was controlled by a senior charioteer (dominus et agitator factionis), a shift that was part of a wider trend of awarding veteran entertainers with managerial positions. In addition to charioteers, each faction had a support staff of several hundred coaches, grooms, doctors, and other assistants (see, for example, CIL 6.10046 = ILS 5313, discussed in Chapter 39). The high level of specialization within the factions produced an internal hierarchy that can be clearly seen among charioteers: a chariot driver who raced a two-horse team (biga) was known as an auriga (or bigarius), while one who achieved a win with a team of four horses (quadriga) was known as an agitator (or quadrigarius) and thus was in the “premiere league.”

The factions were international enterprises: charioteers were drawn from all over the Empire, while racehorses were bred on private and imperial stud farms in Spain, Sicily, Thessaly, North Africa, and Cappadocia (Asia Minor). Unlike the harsh treatment animals endured in other spectacles, racehorses were greatly admired, in some cases becoming major celebrities in the same way as their drivers or other public figures. The poet Martial noted dryly that “Martial is known to the nations and to the people. Why do you envy me? I’m no more famous than Andraemo the horse” (Epigrams 10.9.50, trans. D. Shackleton Bailey).

Like other public performers discussed in this volume (see Chapter 39), charioteers occupied an unusual place in Roman society, at once famous and infamous. Our primary source of information about their social status is inscriptions on honorific and funerary monuments, which, together with other inscribed objects, provide us with the names of more than two hundred different charioteers (cataloged in Horsmann 1998). While we are uncertain about the legal status of more than half of those individuals, the epigraphic evidence informs us that 66 were servi (slaves), 14 were liberti (freedmen), 13 were servi or liberti, and only one was an ingenuus (a freeborn citizen). Thus charioteers – like other categories of Roman entertainers such as gladiators and actors – were almost exclusively of low status. Most were slaves (whose participation in the games might eventually win them their freedom), hired freedmen, or foreigners (Greeks especially); they were not, in the main, freeborn Roman citizens in search of fame and fortune.

In fact, freeborn Romans were discouraged from pursuing a career on the track, by both social censure and legislation that was first enacted in the Early Empire. That legislation designated charioteers as infamis, or persons lacking in honor, who were barred from holding public office. When elite freeborn citizens performing as charioteers appear in the literary sources, authors hold them up as cautionary tales. A prime example is provided by Nero, who was alleged to have idolized charioteers as well as to have pursued a racing career himself – an ambition that Tacitus labeled a foedum studium (“disgraceful desire”) and read as symptomatic of his defective character (Annals 14.14.1). Nero’s disgrace was somewhat lessened by his choice of chariot racing, which was considered less shameful than stage performances or gladiatorial fights because equestrianism of all forms, owing to the expense involved, had aristocratic overtones. In addition, the emperor chose to perform in private, thus limiting the degree of public exposure involved in pursuit of his hobby.

Because of their highly public personas but lowly origins and status, charioteers were frequently the subject of bitter invective from (mostly elite) authors. They were criticized for competing publicly for money and for winning astronomical amounts of it (Juvenal Satires 7.105–14); for their lionization as public heroes with honorary statues (Galen De praenotione ad Posthumum (Epigenem) Kühn 14.604); for their large, fanatical entourages (Pliny Natural History 29.10); and for their special access to and corrupting influence on emperors (albeit mostly “bad” ones, such as Caligula and Nero). These authors’ outrage is magnified by many charioteers’ status as mere slaves (Dio Chrysostom Orations 32.75). The criticism of charioteers, who are often lumped in together with other public performers, is not an isolated phenomenon; rather, it reflects wider status anxieties as the cultures of Rome’s elite and its new popular heroes “interfaced” (see further Toner 1995: 78 and Chapter 41 in this volume). This tension between elite and popular culture is encapsulated in Martial’s Epigrams, where he decries charioteers as the overpaid posterboys of Rome’s lowbrow society (10.74) and yet, elsewhere, bestows undying fame on one of them, the prematurely deceased Flavius Scorpus, as the “darling of the noisy circus, the talk of the town and your short-lived darling, Rome” (10.53, trans. D. Potter).

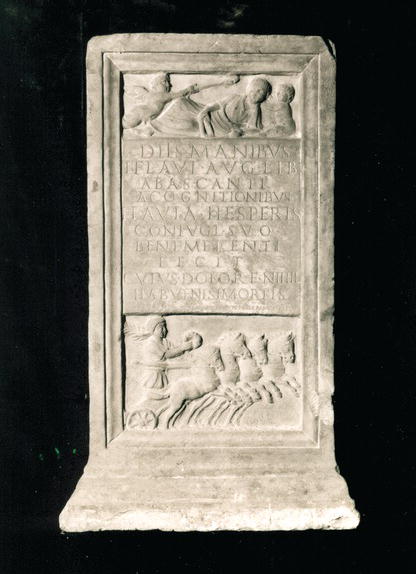

The paradoxical position of charioteers in Roman society and the hypocrisy inherent in their treatment as both gods and monsters was not lost upon all literary observers (e.g., Tertullian On Spectacles 22.3–4). However, it is only by turning to charioteers’ own monuments that we can reconstruct some measure of their lived reality as historical actors as well as their self-understanding as a group. The recently published funerary inscription of the auriga Sextus Vistilius Helenus (AE 2001: 268; Thuillier 2004), for example, provides a snapshot of a driver-in-the-making whose career was tragically cut short. This nine-line text informs us that Helenus had recently been transferred from the Green faction, where he was under the tutelage of a coach named Orpheus, to the Blues, where he was coached by Datileus, when he died at age 13. Helenus is referred to as an auriga under the care of an apprentice (doctor). This inscription confirms that athletes moved between factions like free agents (though some were still slaves and bought) and that the competition for rising stars must have been great. In Helenus’s case, the Blues likely had managers or talent scouts who spotted the promise of this f lorens puer (blooming lad). In addition, it supports the belief that many charioteers started their training at a very young age; Helenus had presumably been racing for several years already. The recently discovered bronze statuette of a child charioteer of African extraction (Figure 33.1) – the first image of its kind in Roman art – offers a visual parallel to young Helenus and, even more so, to Crescens, a Mauretanian charioteer who also began his racing career as a boy (CIL 6.10050 = ILS 5285; see Bell and Dövener forthcoming).

Figure 33.1 Bronze statuette of an African child charioteer (discovered in Altrier), second century CE. Source: Musée national d’histoire et d’art Luxembourg, inv. n. 2004–15/1750, © MHNA Luxembourg/T. Lucas.

Finally, Helenus’s premature death reminds us of the riskiness of his profession and the reputations that racers as a result developed as both good-luck bringers and sorcerers. Roman charioteers tied reins around their waists, increasing not only their maneuverability but also their risk of dragging, injury, and death in the event of a crash. While the causes of charioteers’ deaths are not always explicitly stated, the dangers of the racetrack are clearly suggested by graphic literary similes (e.g., Cicero Republic 2.68), medical remedies prescribed for race-related injuries (Pliny Natural History 28.237), and funerary inscriptions for young drivers whose lives ended suddenly (e.g., CIL 6.10049 = ILS 52862). The sheer luck (and not just skill) they required in navigating their chariots at breakneck speed, especially around the treacherous turns of the metae, gave them a reputation as inherently charmed individuals. Romans thought that they could counteract charioteers’ good fortune with curse tablets or harness it by wearing their images on finger rings or amulets, some of which were inscribed with commands that echoed the emphatic chants of the crowd (e.g., “Go X!” “Hail X!” “Win!”). At the same time, the inherent riskiness of their profession, combined with their slave (or former slave) status and reputation for hooliganism, associated charioteers in legal codes and the popular imagination with the dark arts.

For charioteers who survived and succeeded, even for a relatively short time, a racing career could bring fame and wealth on a scale unthinkable to most Romans. In this context the inscriptions belonging to the premiere class of charioteers or miliarii (i.e., winners of a thousand victories or more) deserve special attention: P. Aelius Gutta Calpurnianus (CIL 6.10047 = ILS 5285), C. Appuleius Diocles, Flavius Scorpus, and Pompeius Musclosus (the latter three in CIL 6.10048 = ILS 5287). These texts provide us with a full digest of their abilities and achievements, including the honoree’s faction, the number of races and victories, the value of the prizes, the categories of the races (e.g., the prestigious race directly after the opening procession), the names of the horses, the number of horses (races with a quadriga are standard), and much more. The meticulous catalogs and self-conscious references to rivals’ records reflect a sense of professional pride that finds parallels in the funerary monuments of gladiators. Not unlike baseball players today, career statistics formed a central part of their identities, and these seemingly dry facts and figures seeped into the Roman popular consciousness as conversations about their technical abilities and tactical choices. In addition, some drivers achieved wealth on a staggering scale. Diocles amassed a fortune of more than 35 million sesterces over the course of his 24-year career, making him richer than most senators. By contemporary standards he was the Tiger Woods of his day, perhaps even “the best paid athlete of all time” (Struck 2010).

Certain charioteers’ wealth and social status were further enhanced by emperors who fraternized with them and rewarded them with gifts (Suetonius Caligula 55.2–3) or even appointed them to political office (Scriptores Historiae Augustae Elagabalus 6, 12). This celebrity extended far beyond the circuses and imperial palaces at the capital alone and evolved into an international “star cult.” While never fully socially accepted on account of their public professions and lowly origins, charioteers’ financial success and celebrity reflected the unusual opportunities afforded by Rome’s spectacle-driven society.

As discussed elsewhere in this volume (see Chapter 29 on material evidence), the direct experiences of everyday Roman spectators are difficult to recover. They do not feature prominently in the extant literary sources, the elite authors of which drew a sharp contrast between their own high-minded disinterest in the chariot races and the vulgar masses (plebs urbanum) such games attracted. (It is noteworthy, however, that many of these accounts betray a strikingly intimate knowledge of the very events their authors claim to shun and detest.) Pliny the Younger’s well-known letter is representative of this genre, where he concludes, “When I think how this futile, tedious, monotonous business can keep them sitting endlessly in their seats, I take pleasure in the fact that their pleasure is not mine” (Letters 9.6, trans. B. Radice).

Like many authors, Pliny frames his critique in terms of social status, which places it within a long-standing tradition of social criticism of the games (see further Chapters 27 and 41). Rather than devoting their leisure time (otium) to pursuing the same learned (i.e., literary and philosophical) pursuits that Pliny and his peers do, spectators indulge their “childish passion” in the circus. Worse still, they allow themselves to become emotional and violent, and generally lose all self-control, even though seemingly nothing is at stake. Despite their inherent biases, some of these critiques hit on a central truth: that from the perspective of the invested spectator, everything was at stake. Ammianus Marcellinus, writing three centuries after Pliny about “the idle and slothful commons,” notes, “Their temple, their dwelling, their assembly, and the height of all their hopes is the Circus Maximus” (28.4.29, trans. J. Rolfe).

The fact that the real target of Pliny’s letter was “respectable men” who forgot their proper social station in attending the races points to a larger reality: the passion for chariot racing touched Romans of every age, sex, and social class. The so-called furor circensis is said to have developed early, as if etched into Romans’ very DNA: “Again, there are the peculiar and characteristic vices of this metropolis of ours, taken on, it seems to me, almost in the mother’s womb – the passion for play actors, and the mania for gladiatorial shows and horse-racing” (Tacitus Dialogues 29.3–4, trans. W. Peterson). Children are recorded not only as passionate about the sport but also as partisans of particular charioteers, horses, and factions, such as young Nero’s support for the Greens (Suetonius Nero 22.1). Nor were such passions limited to boys; archaeological evidence from girls’ tombs (e.g., game tokens, inscriptions) suggests their shared interest as well. More than any other venue for spectacles, the circus was a microcosm of Roman society that embraced young and old, male and female, rich and poor, slave and free, native and foreign, even members of the intelligentsia such as the historian Tacitus, who had a learned exchange with a Roman knight in the circus stands (Pliny the Younger Letters 9.23).

What was the appeal? A day at the circus could be hot, noisy, and dirty, but it held many attractions besides the thrill of the races themselves and their accompanying spectacles. The lack of a velarium (fabric canopy), in contrast to the Colosseum, meant that spectators were exposed to the sun’s blinding glare and sweltering heat, especially uncomfortable for those observing its code of dress (a toga without a coat). While the glare of the sun made it difficult to see, the roar of the crowd made it difficult to hear, both problems that the signaling system of trumpets and lap counters somewhat alleviated. Seats at the circus, which are described as narrow, hard, and dirty, could add to the discomfort. However, because “the law of the place” allowed men and women to sit beside one another, the circus held out the promise of a chance romantic encounter that sexually segregated seating at the theater and amphitheater forbade (Ovid Art of Love 1.135–70). Ovid counsels his readers to exploit their cramped quarters to pick up attractive female spectators: “Nor let the contest of noble steeds escape you; the spacious Circus holds many opportunities” (1.135–6, trans. J. Mozley; cf. Amores 3.2 and Henderson 2002).

Opportunity and chance also lay behind the other major attractions of the races: prizes, betting, and curses. Nero and Hadrian, among others, staged imperial “giveaways” in which tiny inscribed balls were thrown into the stands and the audience members who caught them could claim prizes such as food, clothing, and animals (Dio Cassius 62.18.2, 69.8.2). Placing wagers was rife (Tertullian On Spectacles 16.1; Martial Epigrams 11.1.15), and the outcome of such risk taking, whether positive or negative, could be swift and emotional. Epictetus (1.9.27) discusses a commoner who fainted in the stands after the horse he bet on won a come-from-behind victory, while Juvenal (Satires 11.194–6) censures a praetor for losing his fortune betting on the very games he organized. Juvenal captures all of these elements of the experience – the heat, the noise, the betting, and the crowd’s topsy-turvy state – when he grouses about the circus clamor that interrupts his dinner party:

A roar strikes upon my ear which tells me that the Green has won; for had it lost, Rome would be as sad and dismayed as when the consuls were vanquished in the dust of Cannae. Such sights are for the young, whom it befits to shout and make bold wagers with a smart damsel by their side; but let my shrivelled skin drink in the vernal sun, and escape the toga. (Satires 11.197–204, trans. G. Ramsay)

Emotions ran especially high for fans, who might even attempt to influence the outcome of the races by employing lead curse tablets (defixiones), which they activated through burial at the starting gates or on the racetrack. (Most of the relevant defixiones are from North Africa; on curse tablets, see Chapter 40.) These tablets were inscribed by magicians with visceral images and violent, detailed curses that summon demons to maim or kill competitors and/or their horses. They attest not only to the financial but also the psychological investment that many fans made in their human and equine heroes. Indeed, such was the level of the crowd’s passion that it sometimes boiled over into violence, as seen in rioting at chariot races in Alexandria (c.71–c.75 CE) (Philostratus Life of Apollonius of Tyana 1.15, 5.26).

Even though authors sought to portray the passions in the stands as the “common madness” of Rome’s social underbelly, the furor circensis reached far beyond the arena’s walls and penetrated deep into the lifeways of all Romans. The architectural form of the circus was transplanted to elite countryside villas where it was reimagined as hippodrome-shaped gardens (McEwen 1995). The vocabulary of the circus insinuated itself across literary genres, from epic and bucolic poetry (e.g., Vergil Aeneid 2.476–7 and Georgics 1.272–3) to medical texts (e.g., Galen On the Causes of Respiration Kühn 6.469). The dexterity of the charioteers and the speed of the horses were – true to Martial’s words – “the talk of the town,” dissected by riffraff on street corners (Ammianus Marcellinus 28.4.28), replayed by children in classrooms (Suetonius Nero 22.1), and chewed over by guests at dinner tables (Petronius Satyricon 70.13). The costumes of at least one faction spawned imitation clothing for children, whose parents outfitted them with “little green jackets” (Juvenal Satires 5.143–4). And the races and their heroes inspired a broad menu of visual and material culture that catered to every income and style. Lowborn charioteers and bloody racing accidents were tastefully commodified as ivory figurines and domestic wall paintings, while aerial views of the Circus Maximus – “one of the most beautiful and most admirable structures in Rome” (Dionysius of Halicarnassos Roman Antiquities 3.68) – lent an air of borrowed grandeur to workaday clay lamps.

Charioteers’ allure – their popularity, winning records, and reputed magical powers – even influenced how certain Romans chose to be remembered in death (cf. Chapter 28, noting Figure 28.3). The grave altar of Titus Flavius Abascantus (Figure 33.2) commemorates an imperial freedman who worked as clerk of the courts in the late first century. The relief panel that decorates its base features a charioteer racing his quadriga, with an inscription overhead that identifies the figures as (Flavius) Scorpus and his four racehorses Ingenuus, Admetus, Passerinus, and Atmetus. We do not know what motivated the choice of this imagery. However, since Romans invoked charioteers’ good fortune and magical abilities in a wide range of media, Abascantus (or his wife, who commissioned the tomb) may have seen Scorpus’s image as possessing a talismanic quality. The extreme example of a fan appealing to his favorite charioteer for salvation and immortality is provided by Pliny’s account of Felix’s funeral, where “by at last ‘realizing’ the many earlier potential deaths shared vicariously with his idol, the dead man had brought what the games represented directly into life” (Plass 1995: 40–1). For some Romans confronting death, the circus truly was “the height of all their hopes.”

Figure 33.2 Marble funerary altar of T. Flavius Abascantus, 95 or 98CE.Source: Palazzo Ducale (Museo Lapidario), Urbino, inv. no. 41117, © Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici delle Marche.

When taken as a collective, the literary sources and the visual and material culture demonstrate that the circus games were much more than public, ceremonial occasions; they were events that could play a significant role in the way that Romans at all levels of society structured their private experiences, both inside and outside the circus. To be sure, a chief attraction of attending the games was their edge-of-your-seat, high-speed spectacle: the opportunity to witness a favorite faction, charioteer, or horse prevail while risking life and limb and, at the same time, to watch rivals suffer spectacular crashes in defeat. Nor can we discount the power and appeal of the other kinds of events staged there, from the wild animal displays that transformed spectators into vicarious tourists of Rome’s far-flung empire (see Chapter 34) to the religious processions that encouraged the communal reenactment of the city’s deep past. And yet for many spectators, race days might also entail thrilling moments of personal revelation – of winning a prize or a bet, of discovering a lover in the stands, of seeing a curse fulfilled, of finding salvation in a hero or losing all hope witnessing his death. Romans came to the circus not only to live in the hypercharged present, to see and be seen within the collective hive, but also to imagine an escape from their own mundane lives, perhaps even to alter their fates. The potential for such moments of revelation, set against the backdrop of high drama, undoubtedly explains why, hundreds of years after he wrote them, Juvenal’s words still rang true: “All Rome today is in the Circus” (Satires 11.197).

ABBREVIATIONS

AE = Année Epigraphique

CIL = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

ILS = Inscriptionum Latinarum Selectae

NOTES

1 All dates are CE unless otherwise indicated.

2 CIL 6.10049 = ILS 5286 was carved on a funerary monument erected in memory of two brothers, ages 20 and 29, by their father, Polyneices, who was himself a charioteer.

REFERENCES

Attridge, H. W., J. J. Collins, and T. H. Tobin, eds. 1990. Of Scribes and Scrolls: Studies on the Hebrew Bible, Intertestamental Judaism, and Christian Origins Presented to John Strugnell on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday. Lanham, MD.

Baldwin, B. 1979. “The Acta Diurna.” Chiron 9: 189–203.

Beacham, R. 1999. Spectacle Entertainments of Early Imperial Rome. New Haven.

Bell, S. and F. Dövener. Forthcoming. “An African in Luxembourg. A Newly Discovered Bronze Statuette of a Child Charioteer from Altrier.”

Bell, S. and H. Nagy, eds. 2009. New Perspectives on Etruria and Early Rome. Madison.

Bell, S. and C. Willekes. Forthcoming. “Horse Racing and Chariot Racing.” In G. Campbell, ed.

Bergmann, B. and C. Kondoleon, eds. 1999. The Art of Ancient Spectacle. New Haven.

Cameron, A. 1973. Porphyrius the Charioteer. Oxford.

Cameron, A. 1976. Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium. Oxford.

Campbell, G., ed. Forthcoming. The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life. Oxford.

Coleman, K. and J. Nelis-Clément, eds. 2012. The Mounting of Spectacles in the Roman World / L’organisation des spectacles dans le monde romain. Geneva.

Curran, J. 2000. Pagan City and Christian Capital: Rome in the Fourth Century. Oxford.

Fagan, G. 2011. The Lure of the Arena: Social Psychology and the Crowd at the Roman Games. Cambridge.

Futrell, A. 2006. The Roman Games: A Sourcebook. Malden, MA.

Gager, J. 1990. “Curse and Competition in the Ancient Circus.” In H. W. Attridge, J. J. Collins, and T. H. Tobin, eds., 215–28.

Gager, J. 1992. Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World. New York.

Garland, R. 2006. Celebrity in Antiquity: From Media Tarts to Tabloid Queens. London.

Green, C. 2009. “The Gods in the Circus.” In S. Bell and H. Nagy, eds., 65–78.

Heintz, F. 1998. “Circus Curses and Their Archaeological Contexts.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 11: 337–42.

Henderson, J. 2002. “A Doo-Dah-Doo-Dah-Dey at the Races: Ovid Amores 3.2 and the Personal Politics of the Circus Maximus.” Classical Antiquity 21: 41–65.

Horsmann, G. 1998. Die Wagenlenker der römischen Kaiserzeit: Untersuchungen zu ihrer sozialen Stellung. Stuttgart.

Humphrey, J. H. 1986. Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. Berkeley.

Hyland, A. 1990. Equus: The Horse in the Roman World. London.

Jordan, D., H. Montgomery, and E. Thomassen, eds. 1999. The World of Ancient Magic. Bergen, Norway.

Junkelmann, M. 2000. “On the Starting Line with Ben Hur: Chariot-Racing in the Circus Maximus.” In E. Köhne, C. Ewigleben, and R. Jackson, eds., 86–102.

Köhne, E., C. Ewigleben, and R. Jackson, eds. 2000. Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Berkeley.

Kyle, D. 2007. Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, MA.

Lee, H. 1983. “The Sport Fan and ‘Team’ Loyalty in Ancient Rome.” Arete: The Journal of Sport Literature 1: 139–45.

Lee-Stecum, P. 2006. “Dangerous Reputations: Charioteers and Magic in Fourth-Century Rome.” Greece and Rome 53: 224–34.

Leppin, H. 2011. “Between Marginality and Celebrity: Entertainers and Entertainments in Roman Society.” In M. Peachin, ed., 660–78.

Lim, R. 1999. “‘In the Temple of Laughter’: Visual and Literary Representations of Spectators at Roman Games.” In B. Bergmann and C. Kondoleon, eds., 343–65.

Marcattili, F. 2009. Circo Massimo: Architetture, funzioni, culti, ideologia. Rome.

McEwen, I. K. 1995. “Housing Fame: In the Tuscan Villa of Pliny the Elder.” RES: Journal of Anthropology and Aesthetics 27: 11–24.

Meijer, F. 2010. Chariot Racing in the Roman Empire: Spectacles in Rome and Constantinople. Translated by L. Waters. Baltimore.

Nelis-Clément, J. and J.-M. Roddaz, eds. 2008. Le cirque romain et son image: Actes du colloque tenu à l’Institut Ausonius, Bordeaux, 2006. Pessac.

Peachin, M., ed. 2011. The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World. Oxford.

Plass, P. 1995. The Game of Death in Ancient Rome: Arena Sport and Political Suicide. Madison.

Potter, D. 2010. “Entertainers in the Roman Empire.” In D. Potter and D. Mattingly, eds., 280–349.

Potter, D. and D. Mattingly, eds. 2010. Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor.

Sande, S. 1999. “Famous Persons as Bringers of Good Luck.” In D. Jordan, H. Montgomery, and E. Thomassen, eds., 227–38.

Struck, P. 2010. “Greatest of All Time.” Lapham’s Quarterly: Blog. August 2, 2010. http://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/roundtable/greatest-of-all-time.php (last accessed June 4, 2013).

Thuillier, J.-P. 2004. “Du cocher à l’âne.” Revue de philologie, de littérature, et d’histoire anciennes 78: 311–14.

Thuillier, J.-P. 2012. “L’organisation des ludi circenses: Les quatre factions (République, Haut-Empire).” In K. Coleman and J. Nelis-Clément, eds., 173–220.

Toner, J. P. 1995. Leisure and Ancient Rome. Cambridge.

Weeber, K.-W. 1994. Panem et circenses. Massenunterhaltung als Politik im antiken Rom. Mainz.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

For overviews of chariot racing, see Beacham 1999; Junkelmann 2000; Kyle 2007; Meijer 2010; Toner 1995; and Chapter 38 in the present volume. Humphrey 1986 remains the authoritative study of the archaeological context of Roman circuses. See also the historical sources collected by Futrell 2006 and the various contributions to Bergmann and Kondoleon 1999 and Nelis-Clément and Roddaz 2008.

On racing practices and racehorses, see Hyland 1990: 201–30 and Bell and Willekes forthcoming. On circus factions, see Thuillier 2012 (Republican and Imperial periods) and Cameron 1976 (Late Antiquity). On religion and the circus, see Green 2009 and Marcattili 2009 (Republican and Early Imperial periods) and Curran 2000 (Late Antiquity). On politics and the circus, see Cameron 1976 and Weeber 1994.

On the social and legal status of charioteers, see Horsmann 1998; Potter 2010; and Leppin 2011 (Republican and Imperial periods) and Cameron 1973 (Late Antiquity). On charioteers as good-luck bringers, see Sande 1999; as sorcerers, see Lee-Stecum 2006. On curse tablets, see Gager 1990 and 1992; Heintz 1998; and Zaleski’s essay on religion in the present volume, Chapter 40.

Circus spectators are the subject of Lim 1999 and Henderson 2002. Fans are not well studied, though see Lee 1983 and Meijer 2010. Plass 1995; Fagan 2011; and Chapter 31 in this volume analyze the social psychology of the crowd at gladiatorial arenas but offer useful comparisons to circus audiences as well. See Garland 2006 on the power of fame and celebrity in Rome, including public performers.