Figure 37.1 The amphitheater at Pompeii, c.70 BCE. Source: Photograph by Roger B. Ulrich. Used with permission.

From the earliest development of the Circus Maximus to the construction of imperial baths, Romans built a remarkable number of monumental public facilities for shows and relaxation, not just in the capital, but across the Empire. Much of the social life of Romans took place in public structures – amphitheaters, circuses, stadia, and theaters – erected to house sport and spectacle. These structures, and the events that took place within them, fostered a shared sense of community and pride, even among people of different groups and classes.

This essay will focus on what is perhaps the single most distinctively Roman form of architecture – the amphitheater; Chapter 38 in this volume examines other venues used for sport and spectacle.

The permanent amphitheater was usually elliptical in plan with an oval arena that was completely surrounded by seating (see Figure 37.1). The term “amphitheater” is derived from the Greek adjective amphitheatros/-on, meaning “surrounded by seats,” “seats on all sides.” Although other types of shows, such as beast hunts and aquatic displays, were also staged in amphitheaters, these structures were always most closely associated with gladiatorial games (Wilson Jones 1993; Golvin and Reddé 1990).

A particular challenge for the study of these buildings is the use of the word “amphitheater” by both modern and ancient writers. It is common in English usage to find the term applied very broadly to any venue for entertainment and spectacle irrespective of architectural form. This is not only misleading, but also can be incorrect. There are similar difficulties with the ancient sources. Starting in the late first century BCE the specific Greek word amphitheatron was gradually applied to this type of building with an oval arena surrounded by seats (Coleman 2003: 66–7), but before then it had no standard designation. Even in later periods, inscriptions in the eastern Roman provinces sometimes refer to a simple theater using the Greek term amphitheatron (Robert 1940: 33 n. 6), presumably describing the nature of the seating. Unless there is surviving archaeological evidence associated with the inscription in question, the nature of the building referred to can be unclear.

Figure 37.1 The amphitheater at Pompeii, c.70 BCE. Source: Photograph by Roger B. Ulrich. Used with permission.

Amphitheaters, like any other class of Roman building, have to be examined against the broader canvas of the Roman world. Regional studies run the danger of missing the bigger picture, and it is misleading to fall back on an “East versus West” frame of reference. It is, moreover, important for scholars to include all the available evidence (epigraphic, artistic, documentary) in their interpretation and to be aware of the shortcomings of that evidence.

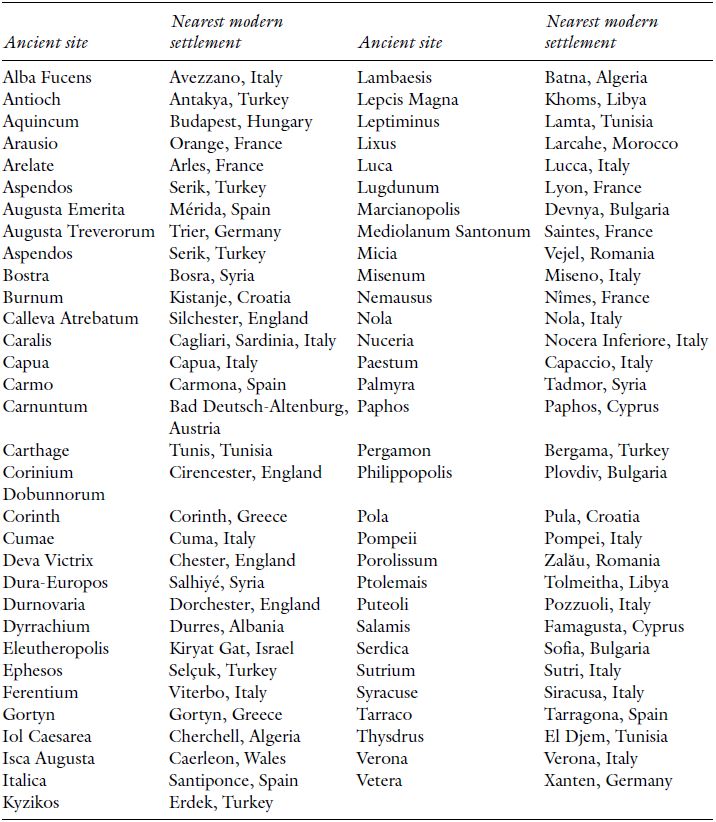

The sheer number of relevant sites makes it impossible within the bounds of this essay to provide detailed maps showing the precise location of each site. In the discussion that follows, most references to lesser-known ancient sites are followed, in parentheses, with the name of the modern-day country in which they are located. At the end of this essay there is a list of all the ancient sites named in the text and the nearest modern-day settlement. Readers interested in precisely locating individual ancient sites are encouraged to make use of the list in conjunction with an Internet-based mapping program.

The earliest gladiatorial shows (munera) in Rome were held in the first half of the third century BCE; the earliest permanent amphiteater in Rome was built in the middle of the first century BCE. (On munera, see Chapter 25.) Gladiatorial shows were initially staged in the political and symbolic heart of the city, the Forum Romanum (Vitruvius On Architecture 5.1). The Forum probably continued to be used as an arena into the early part of the Imperial period (31 BCE–476 CE), after which time other venues became available (Suetonius Tiberius 7.2) (see Map 25.1 for a plan showing the location of spectacle sites in Rome).

As munera grew in complexity and popularity, facilities, mostly temporary in nature, developed to accommodate spectators (Coleman 2000: 219–20). The design of the wooden seating erected for gladiatorial displays in the Forum may have provided a model for the ovoid plan of early permanent amphitheaters such as that at Pompeii (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 56–8; Welch 2007: 30–71). Julius Caesar, seeking to enhance the experience of those attending shows he was staging, apparently stretched awnings over the whole Forum on several occasions (Pliny Natural History 19.23).

In addition to the efforts made to accommodate the needs of spectators, the Forum received modifications to make it more suitable for munera. Excavations under the paving of the Forum have uncovered a central corridor with four lateral arms bisecting it at regular distances of 15 meters. Access up into the open piazza was provided by 12 shaft openings. Traces of installations in these galleries, which excavators dated to the mid-first century BCE, are reminiscent of the system of cages and pulleys for winching performers and animals up into the arena that would later be installed beneath the flooring in some amphitheaters (Carettoni 1956–8; Coleman 2000: 227–8).

Gladiatorial shows were also staged in a number of other sites in Rome, particularly before the construction of the Colosseum in the first century CE. One of the more unusual of such sites was the extraordinary building put up by C. Scribonius Curio in 52 BCE for funeral games in honor of his father. Two theaters were constructed next to each other (back-to-back or side by side, it is unclear which), both attached to some kind of revolving pivot. In the morning separate dramatic performances took place. Then, at some point, the theaters were revolved to form one enclosed structure wherein Curio staged gladiatorial fights (Pliny Natural History 36.116–20). This was not only technically demanding but also dangerous (apparently some spectators remained in their seats) and provided a spectacle in its own right! Curio’s rotating theaters may have been at least partly responsible for the elliptical form of later, permanent amphitheaters.

It was not until 29 BCE that Rome received its first permanent amphitheater, which was built by T. Statilius Taurus somewhere in the southern portion of the Campus Martius. It was financed by the manubiae (a general’s share of the booty) he received after his successful campaigns in Africa (Dio Cassius 51.23.1; Suetonius Augustus 30.8; Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 52–3; LTUR I. 36–7). Little is known about this amphiteater except that it was small and built of stone and wood. Dio Cassius referred to it as a hunting theater (theatron kunegetikon), and it was probably never used as a fully public venue. It was destroyed in the fire of 64 CE.

Nero constructed a particularly sumptuous temporary wooden amphitheater in 57 CE on the Campus Martius. It was claimed he even held aquatic displays in this structure (Suetonius Nero 12; Tacitus Annals 13.31).

There has been much discussion among modern scholars about the origins of both gladiatorial shows and the development and spread of the amphitheater as a building type in Italy (Futrell 1997: 9–29; Bomgardner 2000: 32–60; Welch 2007: 38–71). It has become clear that the amphitheater is a purely Italo-Campanian monument without Greek architectural antecedents.

The earliest permanent amphitheaters were constructed in Campania (the region south of Rome) at sites such as Capua, Cumae, Nola, and Puteoli. Very few of these can be dated more closely than the first century BCE, and only two roughly contemporary examples have been identified in Etruria (the region north of Rome), at the sites of Sutrium and Ferentium (Welch 2007: 192–251).

The earliest extant and closely datable amphitheater, that at Pompeii, was completed between 70 and 65 BCE (Figure 37.1). According to the dedicatory inscription, C. Quinctius Valgus and Marcus Porcius, chief magistrates (duoviri) of the new colonia (“colony”) established at Pompeii in 80 BCE,1 paid for the structure with their own money (CIL 10.852). Interestingly, the building is referred to as a spectacula in the inscription; this word was more usually used for the displays themselves, and its appearance in this inscription is an indication of the newness of the building type specifically designed as a site for spectacles. It was constructed on the eastern side of town just within the walls, and measures 135 by 105 meters externally. In common with other contemporary amphitheaters, it was not provided with the vaulted substructures characteristic of many later examples, and support for the seating was formed by upcast from digging down into the ground to create the sunken arena. At the exterior upper level ran a buttressed retaining wall of Roman concrete with a facing of opus incertum (small irregularly shaped blocks) (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 33–7; Welch 2007: 74–7; see Jacobelli 2003: figs. 44–52 for color illustrations).

A famous wall painting found in the peristyle garden of the House of Actius Anicetus at Pompeii provides a unique contemporary view of the amphitheater at Pompeii (Jacobelli 2003: 71–3 and fig. 58). The occasion depicted is a riot that took place in and around the Pompeii amphitheater in 59 CE between spectators from Pompeii and the neighboring town of Nuceria. This incident, one of the earliest examples of spectator violence in a sporting context, is mentioned by Tacitus (Annals 14.17). The resulting deaths apparently led to a 10-year ban on Pompeii holding gladiatorial shows. In the wall painting refreshment stands outside the amphitheater are very clear, such facilities being rather important given that the program of events could last the full day.

It is not by accident that most of the earliest amphitheaters appeared in towns in Italy that had particularly close ties with Rome, notably coloniae founded for army veterans (e.g., Paestum and Capua; see Welch 2007: 72–101). Such centers also provided the context for the earliest amphitheaters in the provinces, for example at Carmo (Spain), Corinth (Greece), and Antioch (Turkey) (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 41–2, 138; Welch 2007: 255–9; Dodge 2009).

Amphitheaters at Pompeii and elsewhere that were constructed toward the end of the Roman Republic (509–31 BCE) are characterized by a number of significant design features: a relatively simple architectural form, an elliptical arena surrounded by seating that maximized use of the surrounding topography for support, and the absence of arena substructures. Some of them were partially rock-cut, as at Sutrium (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 40–1; Welch 2007: 246–8), and any built elements were provided in a mixture of stone and concrete with a facing of opus incertum or more often of opus reticulatum (small, square blocks laid in a diamond pattern); the latter is in some cases rather irregular, causing some scholars to use the ambiguous term quasi-reticulatum (see, for example, Coarelli 1977: 9–16).

The aforementioned fresco showing the amphitheater at Pompeii also supplies the clearest depiction of the awnings (vela, velaria) that provided shelter to the audience. These awnings are often mentioned in extant advertisements in Pompeii for gladiatorial games.2 The provision of awnings at spectacles is also mentioned in a number of literary sources. Lucretius (4.71–84) describes the fluttering of yellow, red, and dark purple awnings “over a great theater” (possibly the Theater of Pompey), and Pliny the Elder (Natural History 19.6.23–4) notes that awnings were stretched over the Forum in 78 BCE by means of some kind of cable system.

No corbels (supports that protrude from masonry) are preserved on the exterior of the Pompeii amphitheater today, but a number of other structures elsewhere in the Roman world have external corbels for masts that held the ropes for such awnings. In addition to the Colosseum in Rome, the Imperial period amphitheaters at the ancient sites of Pola (Croatia), Nemausus and Arelate (France), and the theaters at Arausio (France) and Aspendos (Turkey) have extensive surviving evidence for awnings. In the Colosseum these were operated by a detachment of sailors from the fleet at Misenum (Italy) (Scriptores Historiae Augustae Commodus 15.6; Montilla 1969; Scobie 1988: 222–3; Connolly and Dodge 1998: 199–200 with color illustrations).

Some scholars identify the stone bollards set into the pavement outside the façades of both the Colosseum and the Imperial period amphitheater at Capua as part of the winch system. However, if this was the case, they would have provided a major obstruction to spectators as they entered and exited the building. The bollards were most likely for some form of crowd control barriers, as seen in many modern sports venues (Connolly 2003: 63–5).

The construction of an amphitheater was a demanding undertaking. The wraparound seating required both major substructures and multiple access points for spectators. There had to be secure areas where animals and gladiators could be lodged and assembled before performances, and these had to be segregated from the auditorium. These needs were provided in different ways.

Advances in building technique in the last two centuries BCE meant that it was increasingly possible to provide vaulted supports for seating, as seen in the Colosseum. Similar arrangements are found in amphitheaters at ancient Nemausus and Arelate (France) and at Thysdrus (El-Djem, Tunisia).3 An available slope or hillside would be incorporated into the design wherever possible to economize on building materials, for example at Mediolanum Santonum (Saintes, France), where the structure was built into a narrow valley (Figure 37.2), and at Pergamon (Turkey), where the amphitheater straddled a steep-sided stream bed (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 124–6, 203). Even the Colosseum made use of the depression left by the drained lake of Nero’s Golden House (Welch 2007: 130–4).

Figure 37.2 The amphitheater at Saintes, France (ancient Mediolanum Santonum), c.40 CE. Source: Myrabella. Used with permission.

The simpler, sunken construction of the amphitheater at Pompeii continued to be used, for example at Leptiminus (Tunisia) (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 132). Arena substructures were sometimes a secondary insertion, as at Augusta Treverorum (Germany), where dendrochronological analysis (tree-ring dating) suggests they were added to the late first-/early second-century CE amphitheater in the late third century CE (Kuhnen 2009: 98).

There are also a number of examples of wholly or partly rock-cut structures, for example Caralis (Sardinia), Italica (Spain), and Ptolemais in Cyrenaica (Libya). At Lepcis Magna (Libya) the amphitheater was built into an old quarry (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 83–4, 97, 200–2, 208).

Welch has demonstrated that the provision of amphitheaters in Italy and the western provinces in the Late Republican and Early Imperial periods can be linked to settlements of veterans or army training (Welch 2007: 88–91). With many of the early permanent amphitheaters, such as those at Pompeii and Sutrium, built in coloniae made up of veterans, they came to represent an important display of Rome’s power and culture. In the Early Imperial period, amphitheaters are often found in association with coloniae or provincial capitals, for example Augusta Praetoria and Alba Fucens (Italy), Augusta Emerita (Spain), and Carthage (Tunisia) (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 82–3, 109–10, 122–3; Bomgardner 2000: 128–41).

The specific urban location of amphitheaters depended very much on local topography and when they were built. They took up a lot of space, and some are found on the fringes of or outside the main town site. At Pompeii and Augusta Praetoria (both in Italy) they were included within the fortified area, but at Luca and Verona (also both in Italy) the amphitheaters are outside the walls. Such a location would have facilitated the accommodation of performers in the displays, particularly of animals, with respect to which public safety must have been a critical issue.

Amphitheaters were also an important component of many military bases, especially legionary fortresses in frontier provinces such as Vetera (Germany) and Isca Augusta and Deva Victrix (Britain) (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 80, 88; Futrell 1997: 147–52). This pattern is repeated at Lambaesis (Algeria), and in the Danube region at sites such as Carnuntum (Austria), Aquincum (Hungary), Burnum (Croatia), and Porolissum (Romania) (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 148–56; Le Roux 1990; Sommer 2009).

Smaller military establishments were also sometimes provided with an amphitheater, for example Inveresk (Great Britain), Zugmantel4 (Germany), and Micia (Romania) (Sommer 2009). The poorly preserved amphitheater at Bostra, the provincial capital of Arabia, may also have served the military garrison of the legio III Cyrenaica (Mougdad (al-), Blanc, and Dentzer 1990). A small arena was built into a bath building at Dura-Europos (Syria) in the first half of the third century CE, when the northern half of that space was made into a military compound for the soldiers of the cohors XX Palmyrenorum and other legionary vexillationes stationed there (Rostovtzeff, Bellinger, Hopkins, et al. 1936: 72–7; Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 139; Dodge 2009: 36–7).

The most famous, and most influential, of all amphitheaters in the Roman world is the Flavian Amphitheater, better known today as the Colosseum in Rome (Gabucci 2001; Connolly 2003; Welch 2007: 128–62). Begun by Vespasian in 75 CE on the site of the lake of Nero’s Golden House, it was dedicated in 80 CE by Titus after his father’s death (Dio Cassius 66.25; Suetonius Titus 7.3).5

The surviving dedicatory inscription is particularly instructive (Alföldy 1995). Identified on a block reused in the early fifth century CE, it demonstrates that Titus had his name inserted so that he could claim the glory associated with the Colosseum’s construction and that it was a victory monument, financed from the manubiae of Titus’s sack of the Temple in Jerusalem.

The Colosseum was a grand and monumental building of four storeys, standing on concrete foundations 12 meters deep, with a travertine façade rising to nearly 50 meters (Lancaster 2005). Fittingly, it is the largest of all Roman amphitheaters with outer dimensions of 188 by 156 meters; the arena proper measures 80 by 54 meters. Eighty main load-bearing travertine piers formed the framework of the vaulted substructures. At each level the arches of the façade were framed by engaged columns, the bottom storey being of the Doric order, the second Ionic, and the third Corinthian. The fourth storey, possibly completed by Domitian, was a plain wall with alternating windows and Corinthian pilasters. It is at this level that the corbels for awnings are preserved.

Figure 37.3 The interior of the Colosseum in Rome, c.75 CE. Source: Photograph by Kacan. Used with permission.

Beneath the now lost wooden floor of the arena is an elaborate system of subterranean passages and chambers where animals and gladiators were kept in readiness to be winched up to the arena level or let up along ramps (see Figure 37.3). There has been much debate about the nature, development, and date of these facilities, and it is difficult to disentangle the archaeological and architectural evidence to form a clear picture. Some scholars have suggested that the arena substructures were far less substantial at the time of the building’s inauguration and that they were radically enlarged and remodeled under Domitian (Rea 1988; Coleman 2000: 233–5; Schingo 2000; Gabucci 2001: 148–59). Recent work has not only clarified the phases of the existing permanent structures but also revealed evidence for the first phase of the Colosseum arena (Beste 2000; Rea, Beste, Campagna, et al. 2000). This consisted of a removable wooden floor, which would presumably have facilitated the flooding of the arena for shows under Titus and Domitian as described by Suetonius (Domitian 4.1) and Dio Cassius (66.25.4). (The debate among scholars about whether the Colosseum arena was totally flooded for large aquatic displays during the building’s inauguration is still to be fully resolved; for further discussion see my other essay in this volume, Chapter 38.)

The more substantial substructures that replaced these wooden facilities were much remodeled over the next few centuries (Rea 1988). Such substructures and their access points can be better appreciated in the amphitheaters at Capua and Puteoli (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 180–5, 204–5; Bomgardner 2000: 90–5 with pl. 3.12, 82–7 with fig. 3.5 and pls. 3.3, 3.8–11). In both these examples the arena floors of concrete are still in place and the openings for trap doors for hauling up animal cages can be clearly seen.

The design of the Colosseum also facilitated movement and accommodation of the audience. There were 76 public access points for the estimated forty-five to fifty-five thousand spectators, and the entrance a particular spectator used depended on where he or she was seated, just as in modern sports venues.

From the second century BCE onwards, seating arrangements may have been segregated by social class and gender in some public venues in Rome. The evidence for this practice, which was clearly intended to reify and reaffirm prevailing social hierarchies, has to be gleaned from disparate literary and epigraphic sources (Fagan 2011: 97–120). Members of the Senate sat separately for the first time at Roman games in 194 BCE (Livy 34.54). In 67 BCE the front 14 rows of seats were reserved by law for senators and equestrians (Cicero Letters to Atticus 2.19.3). This was renewed under Augustus (lex Iulia theatralis), when men and women were also segregated (Suetonius Augustus 44.1; Dio Cassius 53.25.1; Rawson 1987; Schnurr 1992). Augustus attempted to extend this to seating arrangements in the temporary wooden arenas constructed for gladiatorial display (Suetonius Augustus 44.2); he would not allow women to watch gladiators unless they sat at the very top of the seating, even though it had been customary in the past for men and women to sit alongside one another to watch such displays. Compliance with Augustus’ regulations must have been less than total since his contemporary, Ovid (Art of Love 1.163–76), could still recommend shows in the Forum as a good opportunity for young men and women to meet.

When the Colosseum was constructed, seating arrangements were much more rigid. The audience was segregated, with a few specific exceptions, by social rank and gender. Segregation and reserved seating in the Colosseum is confirmed by the physical divisions in the seating areas and by inscriptions on the seats themselves (CIL 6.2059, 3207–22, 32099–151, 32152–250; Orlandi 2004: 167–521). Moreover, a vertical drop of 5 meters separated the upper two tiers from the rest, keeping noncitizens, women, and slaves well away from the rest of the audience. Interestingly, segregation by gender was not applied so rigidly in the Circus Maximus, although senators and equestrians were given seats in segregated areas. This may perhaps be explained by the very different proportional relationship between the length and width of the seating areas at these two sites.

Although there is a bias toward Rome in the ancient literature, accumulating evidence from the provinces suggests that there may have been reserved areas of special seating for certain groups in some sites outside of Rome. However, there is not enough evidence to imply a widespread policy of strict segregation as in the auditoria of Rome. Moreover, although seating in the metropolis and in the provinces may have emphasized social order, it also allowed challenges in the form of rival sets of fans. At Lugdunum (France) members of the association of meat sellers would sit together in the amphitheater, and at Nemausus there were reserved blocks of seats for the boatmen (nautae) of the local rivers Rhône, Saône, Ardèche, and Ouzère (CIL 12.3316–18).

Over 230 amphitheaters are known in the Roman world, and many of them can be found in Italy, Gaul, Germany, North Africa, and the Danube region, emphasizing the popularity of arena displays in these areas. The earliest examples of provincial amphitheaters from the Imperial period were constructed in colonies established in the later first century BCE, for example at Augusta Emerita (Spain) in 8 BCE (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 109–10; Durán Cabello 2004). At Lugdunum the amphitheater was constructed in 19 CE by Gaius Julius Rufus, chief priest of the Imperial Cult of the Three Gauls (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 117–18). Forming part of the large sanctuary of the cult, it added a Roman element to an already prominent pre-Roman focal point. At the beginning of the second century CE the amphitheater was considerably enlarged, increasing the estimated seating capacity from three thousand to twenty-seven thousand. The original dedicatory inscription is one of the earliest instances of the use of the term “amphitheater” to refer to the building type (Audin and Guey 1958; Wuilleumier 1963: 79 no. 217).

The earliest amphitheater in North Africa was constructed by the pro-Roman Mauretanian king Juba II (25 BCE–c.23 CE) at Iol Caesarea (Algeria). Its plan, an elongated oval, was perhaps a reflection of the development of the building type in the Forum Romanum in Rome (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 112–14; Bomgardner 2000: 151; Welch 2007: 47–65). It has been suggested that its shape was particularly suited for animal and hunting displays (venationes).

Many amphitheaters in the western part of the Roman Empire were constructed in the first and early second centuries CE. Examples of such amphitheaters in the western provinces have been found at the ancient sites of Pola (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 171–3), Syracuse (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 115–16), Mediolanum Santonum (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 124–6), Nemausus and Arelate (Bomgardner 2000: 106–20; Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 184–90), and Tarraco (Dupré i Raventós 1994: 81–2; Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 164–5). One of the more notable amphitheaters in North Africa was built in 56 CE at Lepcis Magna (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 83–4; CIL 8.22672). The well-preserved building at Thysdrus, the largest amphitheater in North Africa, may not have been built until the first half of the third century CE (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 209–12; Bomgardner 2000: 146–51).

In Britain, at least 19 amphitheaters are known altogether, with a number associated with towns, for example, Calleva Atrebatum, Corinium Dobunnorum, and Durnovaria (Silchester, Cirencester, and Dorchester, respectively). Most of these survive only as earthworks, but the amphitheater at London, discovered in 1988, was substantially rebuilt in the second century CE in stone (Bateman 2011).

A development particularly characteristic of central Gaul, Germany, and Britain is that of a hybrid form consisting of a combined amphitheater and theater. A variety of different terms have been used by scholars to refer to this type of arrangement. Golvin, for example, used four different labels: edifice mixte, semi-amphithéâtre, théâtre-amphithéâtre, and théâtre mixte (1988: vol. 1: 226–36). Perhaps a better term, that is more a reference to geographical distribution than an attempt at architectural description, might be “Gallo-Roman” (Sear 2006: 98–101). One of the best known of such structures is Les Arènes in Paris, which consists of an elliptical arena surrounded by standard amphitheater seating except on its west side, where it is flanked by a monumental stage (scaena) (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 225–36; Sear 2006: 237–8). Other examples occur at the modern-day towns of Lillebonnne in France and St. Albans in Britain (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 226–8; Sear 2006: 233–4, 210–11, 197). Similar types of theater/amphitheater are also located at rural shrines in Gaul, for example at Sanxay and Gennes (southwest France). This is presumably a regional manifestation of the Greco-Roman connection between games and cult (Drinkwater 1983: 179–81; Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 226–36; Sear 2006: 204, 230–1).

This variation in building design may have developed for economic as well as pragmatic reasons. Dramatic performances were probably far less popular in these regions than elsewhere in the Empire, and epigraphic evidence suggests that animal displays may have been more common than gladiatorial combats. Thus, it made sense to construct one building that could serve more than one function. Another factor may have been a lower level of elite euergetism compared to other parts of the Roman world. The only example of this type of hybrid theater/amphitheater outside the northwestern provinces is at Lixus (Morocco) (Sear 2006: 271; Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 230–6).

The situation in the eastern part of the Roman Empire is much more complex. A wealth of epigraphic and iconographical material indicating the popularity of arena displays was published in the mid-twentieth century (Robert 1940), and there is also an array of literary evidence. Nevertheless, because only six purpose-built amphitheaters had been identified in the eastern Mediterranean up to the 1980s, the influential view developed that gladiatorial displays and thus their necessary venues were rare in the more “civilized” Greek East (Dodge 2009).

This view now appears to be problematic, in part because of the accrual of new evidence. As a result of research in the last two decades, over 20 purpose-built amphitheaters in the East can now be archaeologically identified. There are also Balkan examples at Marcianopolis, Philippopolis, and Serdica (Bulgaria) as well as Dyrrachium (Albania), with perhaps another dozen known from literary and other sources (Dodge 2009: 32–7; Velichkov 2009). Even more arenas were provided by the modification of other classes of entertainment buildings.

Compared to the western part of the Empire this is still a relatively small number of amphitheaters, particularly given the geographical size of the region, but a startling statistic is how few of these structures have been subjected to any form of archaeological investigation, let alone full excavation. Eleutheropolis (Israel) and Serdica are the only two fully excavated buildings (Kloner 1988; Velichkov 2009).

The earliest recorded instance of gladiatorial displays in the eastern Mediterranean was in a Hellenistic royal context when the Seleucid king Antiochos IV Epiphanes staged games at Daphne near Antioch in 166 BCE (Polybius 30.25–6; Livy 41.20.10–13; Bell 2004: 138–50). However, the earliest amphitheater was not constructed until the later first century BCE (at Antioch), apparently by Julius Caesar (John Malalas 216.21–217.4; Libanius Orations 2.219; Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 42). The simple form of this building, partly rock cut with no arena substructures, was probably similar to the contemporary amphitheaters of Italy. Serdica is also the latest amphitheater known to have been constructed (late third/early fourth century CE, when the city became an imperial capital). Interestingly, it was built over an earlier theater.

None of the amphitheaters in the Roman East have the scale and monumentality of the structures at Nemausus, Augusta Emerita, or Thysdrus, except perhaps those at Kyzikos or Pergamon (Turkey), where the surviving remains of mortared rubble vaulted substructures give an idea of original scale. The more simple form of eastern amphitheaters means that fewer remains tend to survive and makes those remains difficult to identify. Recently, the existence of an amphitheater has been suggested at Palmyra (Syria) based on recently discovered air photographs taken in 1930 (Hammad 2008), although nothing is visible above ground.

A specific political and cultural context for the construction of eastern amphitheaters is known in very few cases (Dodge 2009: 37). Those associated with military establishments followed the pattern already identified in the West, but provision at eastern coloniae and provincial capitals is far less clear than in the West (Welch 2007: 72–127). Corinth and Gortyn (Greece), Paphos (Cyprus), and Bostra (Syria) were all provincial capitals with amphitheaters. On current evidence, Ephesos (Turkey), the provincial capital of Asia, did not possess an amphitheater, although it is the location of the only known gladiator cemetery, discovered in the 1990s (Kanz and Grossschmidt 2009). None have so far been identified in Egypt, although textual evidence implies their existence, for example at Alexandria (Dodge 2009: 37). For only one amphitheater in the eastern Mediterranean is there evidence that it was provided as an act of civic munificence. At Salamis in northern Cyprus, a prominent local citizen, Servius Sulpicius Pancles Veranianus, built or restored the amphitheater in the second half of the second century CE (Dodge 2009: 37).

Thus, many cities of the eastern Mediterranean were never provided with an amphitheater, but to judge from the epigraphic evidence, they hosted gladiatorial and other arena displays on a regular basis. The venues used were many and varied, including stadia and theaters, often modified in ways that were not confined to the eastern Mediterranean (see Chapter 38).

The quintessentially Roman amphitheater was, as a building type, relatively late in reaching its canonical form. Debates about the origins of the amphitheater as a building type have long dominated scholarly work on the amphitheater, although recent research has gone a long way toward clarifying many other points (Futrell 1997; Welch 2007).

Partly as a result of senatorial opposition, permanent amphitheaters were not constructed in the city of Rome until the late first century BCE, despite the fact that they were being provided earlier for other cities in Italy. Literally hundreds of amphitheaters were ultimately constructed throughout the Roman Empire. The most northerly amphitheater occurs in a military context in Scotland, in association with the fort at Inveresk (Neighbour 2002); the most easterly examples have been identified at Palmyra in the Syrian desert and Dura-Europos on the Euphrates River (Hammad 2008). Most amphitheaters in the western provinces were constructed in the first to early third centuries CE, though it should be noted that not every city had one, nor were they always constructed on a monumental scale. In the East, a more complex situation prevailed that involved the limited provision of purpose-built amphitheaters and the much wider modification of preexisting entertainment venues.

Interestingly, the latest amphitheaters were constructed in the third and early fourth centuries CE, at a time when the gladiatorial games themselves were becoming far less frequent. As combat displays declined, arenas continued to provide a venue for the other types of shows with which they had long been associated – animal displays, acrobatics, and dancing. This continuity is evident in the early sixth-century CE writings of Cassiodorus and contemporary artistic portrayals of Constantinople (Cassiodorus Variae 5.42.6–10; Dodge 2009, 2011: 73–6).

List of key ancient sites mentioned in this essay, and corresponding modern sites

ABBREVIATIONS

CIL = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

LTUR = Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae

NOTES

1 Pompeii had a long history before it first came under Roman control in the late fourth or early third century BCE. When many places in Italy attempted an ultimately unsuccessful uprising against Roman power in the early first century BCE, the residents of Pompeii joined the uprising. As a result, the Roman government in 80 BCE settled a substantial number of Roman citizens in Pompeii to help secure control over the site, and those settlers comprised what was known as a colonia. For good introductions to the site of Pompeii and its history, see Guzzo and D’Ambrosio 1998 or Ling 2005.

2 The Latin phraseology in the advertisements is vela erunt, “there will be awnings” (see CIL 4.3884, 1185 and Montilla 1969).

3 On these amphitheaters, see Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 184–90, 209–12. For illustrations of the relevant parts of the Colosseum, see Connolly and Dodge 1998: 190–8.

4 The Roman names of the military establishments at Inveresk and Zugmantel are not known.

5 On Nero’s Golden House, see Segala and Sciortino 1999.

REFERENCES

Alföldy, G. 1995. “Eine Bauinschrift aus dem Colosseum.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 109: 195–226.

Álvarez Martínez, J. M. and J. J. Enríquez Navascués, eds. 1994. El Anfiteatro en la Hispania Romana. Mérida.

Audin, A. and J. Guey. 1958. “Une belle découverte épigraphique à l’amphithéâtre des Trois Gaules.” Cahiers d’histoire publiés par les Universités de Clermont-Lyon-Grenoble 3: 99–101.

Bateman, N. 2011. Roman London’s Amphitheatre. Revised ed. London.

Bell, A. 2004. Spectacular Power in the Greek and Roman City. Oxford.

Beste, H.-J. 2000. “The Construction and Phases of Development of the Wooden Arena Flooring of the Colosseum.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 13: 79–92.

Bishop, M. C., ed. 2002. Roman Inveresk: Past, Present, and Future. Duns, Scotland.

Bomgardner, D. 2000. The Story of the Roman Amphitheatre. London.

Carettoni, G. 1956–8. “Le gallerie ipogee del Foro romano e i ludi gladiatori forensi.” Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma 76: 23–44.

Coarelli, F. 1977. “Public Building in Rome between the Second Punic War and Sulla.” Publications of the British School at Rome 45: 1–23.

Coleman, K. 2000. “Entertaining Rome.” In J. Coulston and H. Dodge, eds., 210–58.

Coleman, K. 2003. “Euergetism in Its Place: Where Was the Amphitheatre in Augustan Rome?” In K. Lomas and T. Cornell, eds., 61–88.

Conforto, M. L., ed. 1988. Anfiteatro flavio: Immagine, testimonianze, spettacoli. Rome.

Connolly, P. 2003. Colosseum: Rome’s Arena of Death. London.

Connolly, P. and H. Dodge. 1998. The Ancient City: Life in Classical Athens and Rome. Oxford.

Coulston, J. and H. Dodge, eds. 2000. Ancient Rome: The Archaeology of the Eternal City. Oxford.

Dodge, H. 2009. “Amphitheaters in the Roman East.” In T. Wilmott, ed., 29–46.

Dodge, H. 2011. Spectacle in the Roman World. London.

Domergue, C., C. Landes, and J.-M. Pailler, eds. 1990. Spectacula, I: Gladiateurs et amphithéâtres. Paris.

Drinkwater, J. 1983. Roman Gaul: The Three Provinces, 58 bc–ad 260. London.

Dupré i Raventós, X. 1994. “El Anfiteatro de Tarraco.” In J. M. Álvarez Martínez and J. J. Enríquez Navascués, eds., 79–89.

Durán Cabello, R. M. 2004. El teatro y el anfiteatro de Augusta Emerita. Oxford.

Fagan, G. 2011. The Lure of the Arena: Social Psychology and the Crowd at the Roman Games. Cambridge.

Futrell, A. 1997. Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power. Austin, TX.

Gabucci, A., ed. 2001. The Colosseum. Translated by M. Becker. Los Angeles.

Golvin, J.-C. 1988. L’amphithéâtre romain: Essai sur la théorisation de sa forme et de ses fonctions. 2 vols. Paris.

Golvin, J.-C. and M. Reddé. 1990. “Naumachies, jeux nautiques et amphithéâtres.” In C. Domergue, C. Landes, and J.-M. Pailler, eds., 165–77.

Guzzo, P. and A. D’Ambrosio. 1998. Pompeii. Rome.

Hammad, M. 2008. “Un amphithéâtre à Tadmor-Palmyre?” Syria 85: 339–46.

Hopkins, K. and M. Beard. 2005. The Colosseum. Cambridge, MA.

Jacobelli, L. 2003. Gladiators at Pompeii. Rome.

Kanz, F. and K. Grossschmidt. 2009. “Dying in the Arena: The Osseous Evidence from Ephesian Gladiators.” In T. Wilmott, ed., 211–20.

Kloner, A. 1988. “The Roman Amphitheatre at Beth Guvrin. Preliminary Report.” Israel Exploration Journal 38: 15–24.

Kuhnen, H.-P. 2009. “The Trier Amphitheater. An Ancient Monument in the Light of New Research.” In T. Wilmott, ed., 95–104.

Lancaster, L. 2005. “The Process of Building the Colosseum: The Site, Materials, and Construction Techniques.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 18: 57–82.

Le Roux, P. 1990. “L’amphithéâtre et le soldat l’Empire romain.” In C. Domergue, C. Landes, and J.-M. Pailler, eds., 203–15.

Ling, R. 2005. Pompeii: History, Life and Afterlife. Gloucestershire, UK.

Lomas, K. and T. Cornell, eds. 2003. Bread and Circuses: Euergetism and Municipal Patronage in Roman Italy. London.

Montilla, R. 1969. “The Awnings of Roman Theatres and Amphitheatres.” Theatre Survey 10: 75–88.

Mougdad (al-), R., P.-M. Blanc, and J.-M. Dentzer. 1990. “Un amphithéâtre à Bosra?” Syria 67: 201–4.

Neighbour, T. 2002. “Excavations on the ‘Amphitheater’ and Other Areas East of Inveresk Fort.” In M. C. Bishop, ed., 47–57.

Nogales Basarrate, T., ed. 2002. Ludi Romani: Espectáculos en Hispania Romana. Córdoba.

Orlandi, S. 2004. Epigrafia anfiteatrale dell’Occidente romano. VI, Roma. Anfiteatri e strutture annesse con una nuova edizione e commento delle iscrizioni del Colosseo. Rome.

Rawson, E. 1987. “Discrimina Ordinum. The Lex Julia Theatralis.” Publications of the British School at Rome 55: 83–114.

Rea, R. 1988. “Le antiche raffigurazioni dell’anfiteatro.” In M. L. Conforto, ed., 23–46.

Rea, R., H.-J. Beste, P. Campagna, et al. 2000. “Sotterranei del Colosseo: Ricerca preliminare al progetto di ricostruzione del piano dell’arena.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 107: 311–39.

Robert, L. 1940. Les gladiateurs dans l’Orient grec. Paris.

Rostovtzeff, M. I., A. R. Bellinger, C. Hopkins, et al. 1936. The Excavations at Dura-Europos, Preliminary Report of Sixth Season of Work, October 1932–March 1933. New Haven.

Schingo, G. 2000. “A History of Earlier Excavations in the Arena.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 13: 69–78.

Schnurr, C. 1992. “The Lex Julia Theatralis of Augustus: Some Remarks on Seating Problems in Theatre, Amphitheatre and Circus.” Liverpool Classical Monthly 17: 147–60.

Scobie, A. 1988. “Spectator Security and Comfort at Gladiatorial Games.” Nikephoros 1: 192–243.

Sear, F. 2006. Roman Theatres: An Architectural Study. Oxford.

Segala, E. and I. Sciortino. 1999. Domus Aurea. Milan.

Sommer, C. S. 2009. “Amphitheaters of Auxiliary Forts.” In T. Wilmott, ed., 47–62.

Velichkov, Z. 2009. “The Amphitheater of Serdica, Sofia, Bulgaria.” In T. Wilmott, ed., 119–25.

Welch, K. 2007. The Roman Amphitheatre: From Its Origins to the Colosseum. Cambridge.

Wilmott, T., ed. 2009. Roman Amphitheatres and Spectacula: A 21st-Century Perspective. Oxford.

Wilson Jones, M. 1993. “Designing Amphitheatres.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 100: 391–422.

Wuilleumier, P. 1963. Inscriptions latines des trois Gaules (France). Paris.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

A good starting point for the further study of amphitheaters (and the spectacles held in amphitheaters) is Gabucci 2001, a lavishly illustrated work on the Colosseum. Hopkins and Beard 2005 is accessible and insightful on the structure of and seating in the Colosseum. Jacobelli 2003 is brief and focused on Pompeii but well illustrated, readable, and reliable on gladiatorial games.

On the emergence of amphitheaters as a building type in the Republic and on the Colosseum itself, Welch 2007 is now the essential source. Relevant inscriptions are collected in Orlandi 2004. On construction, materials, and elements of the Colosseum, see Connolly 2003 and Lancaster 2005. Recent studies on the wooden floor of the arena include Beste 2000 and Rea, Beste, Campagna, et al. 2000. On amphitheaters and urban settings in Rome, see Connolly and Dodge 1998, Coleman 2000 and 2003, and Coulston and Dodge 2000.

Older but still very useful reference works of broad scope include Golvin 1988; Conforto 1988; and Domergue, Landes, and Pailler 1990. Studies of facilities in different parts of the Empire from London to Bulgaria include Kloner 1988 on Beth Guvrin; Futrell 1997 on European sites and architectural adaptations; Bomgardner 2000 on imperial and North African sites; Kuhnen 2009 on Trier; Nogales Basarrate 2002 on Spain; Dodge 2009 on the Roman East; Velichkov 2009 on Serdica; and Bateman 2011 on London.

On social historical issues (seating, crowds, performers, allure) see Rawson’s classic 1987 essay; Schnurr 1992; and Fagan 2011. Also see Chapters 31, 34, and 35 in this volume.

Finally, Wilmott 2009 is a valuable recent collection of essays on Roman amphitheaters and spectacles, including Kanz and Grossschmidt 2009 on gladiator skeletons from Ephesos.