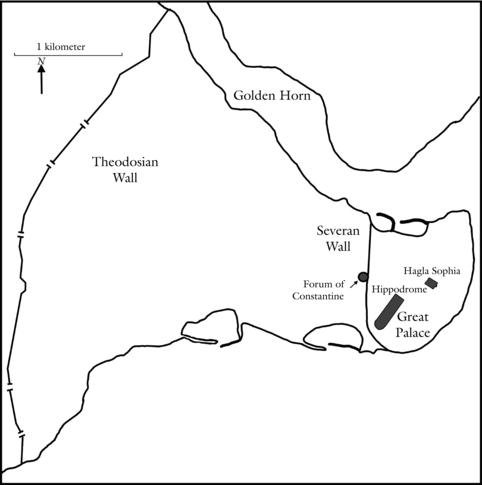

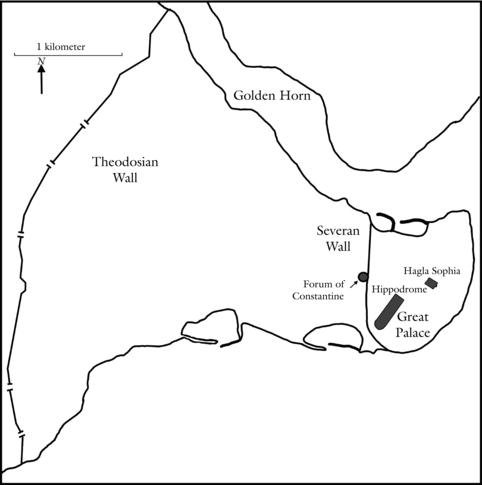

Map 43.1 Plan of Constantinople in the time of Justinian.

In November 561 CE the fans gathered at the chariot races in the hippodrome of Constantinople created a serious disturbance.1 The fans of the Green racing team attacked the fans of the Blue team. When the emperor Justinian heard about the riot, he ordered the commander of his guards to separate the two sides. The guards, however, proved unable to stop or even slow the fight, and it continued with the Blue fans invading the seats of the Green fans, chanting “Burn here, burn there! Not a Green anywhere.” In response, the Greens spilled out of the hippodrome and proceeded to riot in the streets, stoning the people they encountered, stealing property, and chanting “Set alight, set alight! Not a Blue in sight.” The riot lasted all night and into the next morning (Theophanes Chronographia 235–6, trans. C. Mango).

Chariot racing was without a doubt the most popular form of entertainment in the Byzantine world in the sixth through the eighth centuries. Most major cities in the eastern Mediterranean had their own hippodromes where races were held on a regular basis. In each hippodrome the competitors in the races were typically divided into four racing teams: the Blues, Greens, Whites, and Reds.

In the cities for which we have evidence, chariot races were connected with violent riots. It is reasonable to ask why the government tolerated the violence associated with the races and why the races were so popular despite condemnation from the Christian religious authorities. As one ecclesiastical author put it, a hippodrome was nothing more than a “church of Satan” (John of Ephesos Ecclesiastical History 5.17).

This essay will consider the critical social role of spectacle and sport in the Byzantine world. Analysis will be limited primarily to the impact of chariot racing but will also touch upon the other important form of spectacle of the period – the pantomimes of the theater. There were also some sporting events in the period that occurred outside of the theaters and hippodromes, such as hunting, wrestling, and running.2 While these may have been important to individuals, and hunting certainly seems to have been a significant pastime of the upper class, they do not qualify as public spectacles and hence are outside the scope of this essay.

We will concentrate on the sixth century, roughly between the reigns of Anastasius (491–518) and Phocas (602–10), because we are particularly well informed about that era of Byzantine history. Although some of the most accomplished Byzantine historians, including Procopius of Caesarea, wrote during this period, the best literary sources for spectacle and sport are actually the more humble chroniclers rather than traditional historians. Chroniclers such as John Malalas wrote relatively short, simple works that were intended for a slightly less educated audience than longer, more complex narrative histories. This means that these chroniclers tended to focus more on what was popular and felt less constrained to follow historiographical traditions that went back to Thucydides. For our purposes, this means more frank references to popular spectacles, which improve our understanding of their impact on Byzantine society (Cameron 1976: 139).

Although Byzantine society was a direct continuation of Roman society and also retained some features of Greek culture, Byzantine spectacle and sport of the sixth century looked rather different from its Roman and Greek predecessors. By this period, the gladiatorial combats and beast hunts that the earlier Roman world made famous and the tradition of individual athletic competition that included the Olympic Games of the Greek world were both in eclipse.3 By the reign of Anastasius, the two major forms of spectacle in the Byzantine world were the pantomimes of the theater and chariot races of the hippodrome.

The theater was home to some of the most popular figures of the day, and contemporaries were clearly enamored of the acts performed there. The theater of the sixth century, which was bawdier and rather less intellectual than the drama of ancient Greece, was dominated by the performances of dancing pantomimes (Mango 1981: 341–4; Roueché 2008: 680–2). We know something of their performances thanks to the scathing attacks of the somewhat prudish Procopius of Caesarea in his Secret History. He writes that the empress Theodora, in her days as a dancer in the theater, was not ashamed to walk about largely unclothed in front of an audience. Apparently she was famous for an act in which she lay on her back, with only a small cloth covering her groin, and patiently waited for geese to peck grains of barley off of her nearly naked body (Procopius Secret History 9.20–3).

Although Procopius tells this story in an attempt to discredit Theodora, it was clearly acts like this that made the pantomimes of the theater so popular. In fact, pantomime was so important that banning theatrical shows was considered a significant punishment, such as when Justin I banished all the pantomimes in the Empire after a major riot in 522 (John Malalas Chronographia 416–17). The popularity of the theater is further emphasized by the fact that popular disturbances were just as common in theaters as they were in hippodromes, as evidenced by a riot in a theater in Constantinople in 501 that cost three thousand lives (Marcellinus Comes Chronicle a.501). A riot in the theater at Antioch in 529 resulted in Justinian banning theatrical shows in the city (John Malalas Chronographia 448–9). Because of the frequent short-term moratoriums on the theater (due to the riots they incited), spectators in the early sixth century may have gravitated more to the only remaining large-scale public spectacle: chariot races.

In the late fifth century, chariot racing and theater were both standardized across the Byzantine Empire and their administration assumed by the government. Government administration of these spectacles is implied by the statement of John Malalas that the charioteer Kalliopas was “given” by the administration to the Greens in Antioch (John Malalas Chronographia 395–6). It is probably also implied by Procopius’s charge that Justinian diverted to the central treasury the revenues that cities had been raising locally for their own civic needs and public spectacles (Procopius Secret History 26.6). Thus, in typical Byzantine fashion, sport and spectacle were bureaucratized in the late fifth century. The state paid and organized what historians have come to call the “factions” – the professional racing teams of the Blues, Greens, Reds, and Whites.4 Thus, whereas there was competition between these teams on the track, there was no organizational or business competition since all were owned, administered, and paid by the government (Cameron 1976: 5–73). (On the organization of chariot racing in Rome, see Chapter 33 in this volume.)

The best charioteers were revered figures. The most popular and most frequently victorious charioteer of the sixth century was undoubtedly Porphyrius, about whom Alan Cameron has written a definitive book. Cameron counts at least seven statues dedicated to Porphyrius by his fans of both the Blue and Green persuasion, one of which was made partly of gold (Cameron 1973: 221).

The importance of chariot racing in the Byzantine world is evident from the central position of the hippodrome in the capital, Constantinople. The Greek city of Byzantion was founded in the seventh century BCE and became part of the Roman Empire in 129 BCE. It was sacked in 196 CE, during one of the civil wars that convulsed the Roman Empire, by forces under the command of Septimius Severus, who saw to the rebuilding of the city shortly thereafter. Constantine I captured Byzantion in the course of another civil war, and in 330 CE he refounded the city, which became known as Constantinople, and made it the capital of the entire Roman Empire. When the Roman Empire split into western and eastern halves at the end of the fourth century, Constantinople was the capital of the eastern half, which evolved into the Byzantine Empire. Constantinople remained the most important city in the Byzantine world until the final collapse of Byzantine power in 1453 (Bassett 2004: 18–26; Cartledge 2009: 167–76; Jeffreys 2008: 232–94).

The history of the hippodrome in Constantinople starts with Septimius Severus, who seems to have made it part of his rebuilding of the city in around 200. It was probably completed by Constantine I, who built his residence, the Great Palace, alongside it (see Map 43.1). The hippodrome constructed by Severus and Constantine was a typical Roman circus of the period, with an elliptical shape and a track divided by a longitudinal barrier. The seating area reserved for the imperial family, the Kathisma, was on the east side, and hence was situated between the track and the Great Palace.5 The hippodrome was approximately 450 meters long and 118 meters wide and seems to have held about a hundred thousand people (Mango, Kazhdan, and Cutler 1991). (On the architecture of Roman circuses, see Dodge’s essay in this volume on sites other than amphitheaters, Chapter 38.)

Map 43.1 Plan of Constantinople in the time of Justinian.

The hippodrome was in service for most of a millennium and for much of that time it represented one of the most important public spaces in Constantinople. The structure was maintained and remained in use until c.1200, and was not finally dismantled until the construction of the Blue Mosque in the seventeenth century. For a thousand years it served not only as a site for chariot racing, but also as the setting for major political events such as the proclamation of new emperors and the celebration of military triumphs. Its location in the physical heart of Constantinople reflected its role as a focus for public life in the city.

The fan clubs of the factions, especially of the Blues and Greens, form perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Byzantine chariot racing. The members of the factions are typically identified as “partisans” and were the most extreme and dedicated fans of the teams. It is important to note that the partisans were almost always few in number and represented not only an extremely small minority of the whole population, but also a small minority of racing fans generally, the majority of whom were not so radical (Cameron 1976: 74–5). Our only figure for the size of these partisan groups comes from the historian Theophylact Simocatta, who records that in 602 there were 1,500 Green partisans and 900 Blue partisans in Constantinople (Theophylact The History 8.7.11). The partisans were the most rabid fans of their factions in the hippodrome, but they were also the loudest and rowdiest spectators in the theater. As they were the most dedicated and experienced fans, they were also the most skillful leaders of chants in support of their teams and favorite pantomimes (Cameron 1976: 74–156, 193–229).

Aside from their rabid interest in the theater and chariot races, it is important to emphasize that partisans had another thing in common: they were typically young men. The evidence for this is abundant throughout the sources. For example, the historian Agathias approves of Justinian’s giving a young relative a military position in order to “prevent him from dissipating his energies and wasting his substance on wild escapades in the turbulent atmosphere of the Hippodrome with its chariot races and its popular factions, all of which things tend to have a profoundly disturbing effect on the minds of the young” (Agathias The Histories 5.21.4, trans. J. Frendo). Procopius and other historians frequently describe partisans merely as “youths” (neanias) (Procopius Secret History 7.42). We have personal evidence from one historian, Menander Protector, who confesses that after law school (in other words, when he was still a young man) he preferred “the disgraceful life of an idle layabout” and made his interests the chariot races and the pantomimes of the theater (Menander Fragment 1).

These young, rabid partisans of the Blue and Green factions identified with each other and wore clothing that deliberately set them apart from the typical Byzantine male and even from the other less rabid fans of the spectacles. They apparently wore baggy clothing with puffy sleeves and large cloaks so that their clothing would billow out and make a scene when they cheered in the theaters and hippodromes (Procopius Secret History 7.12–13). More than this, the partisans preferred to wear both their hair and their beards long in what contemporaries called the “Hunnic” style (Procopius Secret History 7.10). In the hair and dress of the partisans, and in the disapproving tone that contemporaries use to describe them, one is reminded of the critiques of the “long hairs” of the social revolution of the 1960s. So the partisans of the Blue and Green factions were rabid fans, typically young men, and set themselves apart in their appearance. But their most important and dangerous contribution to society in the minds of contemporaries was certainly their participation in large-scale riots.

Of all the impacts of sport and spectacle in the Byzantine world of the sixth century, riots are perhaps the most frequently cited. There were two major types of riots that hippodrome and theater spectators in general, and the partisans of the Blues and Greens in particular, instigated. The first was a relatively straightforward battle between competing sets of partisans, such as the riot of November 561 described at the beginning of this essay. These disturbances typically took place in response to something that occurred in the hippodrome, such as a resounding victory for one of the major factions, or in the theater, such as a particularly successful act of a pantomime. For many riots these origins have to be assumed, as the sources often do not provide explicit cause for these faction battles. As Cameron has noted, “they were the natural escalation and culmination of faction rivalry, nothing more” (Cameron 1976: 275). These sorts of disturbances usually started inside the hippodrome or theater, often when games or shows were taking place. The importance of these two structures as the center of violence between the partisans of the Blues and Greens should not be underestimated – on occasion a riot between the factions might occur in the hippodrome even when no race was being held, as in Constantinople in April 550 (John Malalas Chronographia 484). Once a riot had begun, it frequently spilled out into the streets, as happened in 561 in the aforementioned incident.

The second major type of riot instigated by faction partisans involved them uniting, rather than attacking each other, and presenting demands to the imperial government. When these demands were not met, the united partisans would proceed to rampage through the city, killing indiscriminately and engaging in vandalism and arson. A riot could begin as this type of disturbance, or a general disturbance of the first type could turn into this kind of riot because of the actions of the government. For example, at Antioch in 507 the overreaction of a government official to a typical faction disturbance resulted in a full-scale war between the government and Green partisans that took many lives (John Malalas Chronographia 396–8). The demands made by rioting faction members were almost always related to their own fan clubs or to chariot racing in general. In 507, there was a serious riot in Constantinople when the Green partisans appealed to Anastasius during the chariot races to release prisoners who had been arrested for throwing stones. When Anastasius refused the request and sent in soldiers to attack the partisans, they proceeded to throw stones themselves at the soldiers and the emperor (John Malalas Chronographia 394–5). It is reasonable to assume that the imprisoned stone throwers who were the subject of the original request were themselves Green partisans.

The Nika Riot of 532 is the most famous and best known of these types of disturbances because it is described in depth by several sources and was resolved by a massacre with an unusually high death toll.6 The riot began typically, with a request for the release of some fellow partisans who had managed to survive a botched execution. If there was something unusual about this request, it was that partisans of both the Blue and Green factions made the request, because it just happened that the surviving prisoners were one partisan from each faction. Although the riot started typically, it escalated quickly. The name given to the disturbance afterward was based on the chant Nika (“conquer!”) that was taken up by the rioters, who rampaged through the city and burned down a number of important structures, including Hagia Sophia. After initial attempts at repression failed, the emperor Justinian took steps to conciliate the rioters, but to no avail, and disturbances continued. Justinian then endeavored to negotiate with the rioters from the Kathisma in the hippodrome, but the assembled crowd disdained his advances and instead acclaimed a new emperor. Justinian was reportedly on the verge of fleeing Constantinople when the empress Theodora intervened and urged him to remain and take forceful countermeasures. Justinian ordered government forces to mount an attack on the crowd in the hippodrome; this resulted in the death of approximately thirty thousand people and effectively crushed the riot. Thanks to the recent scholarship of Geoffrey Greatrex, we know that the Nika Riot had such a catastrophic conclusion because of a series of misunderstandings between the rioting people and Justinian. Greatrex argues that “Justinian constantly gave off different signals to the populace, at one moment seeming lenient, at another uncompromising” (Greatrex 1997: 80). Without this indecision from the emperor, it is likely that the Nika Riot would have been rather shorter than six days, and would not have ended so bloodily.

Riots started by the partisans of the Blues and Greens were fairly common in the sixth century. John Malalas recounts at least nine such disturbances in Constantinople during the reign of Justinian, making for an average of about one riot every four years. Despite the frequency of these riots and the occasionally appalling level of destruction, the emperors clearly tolerated them. This is evident from the fact that they never formally attempted to ban the Blue and Green factions nor ever permanently shut down either the hippodrome or the theater. While the emperors no doubt had many reasons for allowing the partisans to continue their activities, the primary reason was that they needed the partisans.

These young individuals, as we have seen, often prefaced their riots by making requests of the government. The emperors typically ignored the requests since they tended to revolve around the release of partisans who had been convicted of crimes ranging from arson to murder. However, the fact that these partisans were able to voice requests in settings as large as the theater and hippodrome points to a relatively high level of organization. By coordinating their efforts and presenting their requests as simple short chants, the partisans could make their voices heard even in such large public arenas. As Cameron notes (1976: 234–7), the partisans did this in much the same way that claques, small paid groups of professional spectators, directed the audience’s applause in more modern times at the opera.

Of course, the requests of the partisans for the release of their criminal compatriots did not help the emperor, but at other times when there were no such requests to make, the partisans used their abilities to direct the entire audience in the theater or hippodrome in a chant in acclamation of the emperor. For example, in 602 the emperor Maurice used heralds to address the crowd in the hippodrome and assure them that the revolt of Phocas was not serious. He then ordered a series of chariot races to amuse audience. The Blues responded by leading a chant in support of Maurice, assuring him that he would overcome his enemies (Theophylact The History 8.7.8–9). This sort of behavior on the part of the partisans was invaluable to the emperor because it could instantly boost his own popularity, or at least the appearance of it.7 This, combined with the fact that the majority of factional disturbances were directed against the opposing faction instead of against the government, explains why the emperor tolerated both the partisans and the riots that they regularly sparked.

We have now assembled several facts about the culture of Byzantine sport and spectacle in the sixth century and it is time to propose an overarching interpretation that unifies them. Of primary interest are two related questions: why was rioting apparently a popular activity for faction partisans, and why were spectacle and riot so intimately linked? Of course, there were sometimes serious socioeconomic reasons to riot, ranging from famine to political uncertainty. A spectacle in the hippodrome or theater, and indeed a riot that might go along with it, could be an opportunity for the people, as Cameron says, “to leave behind for a few hours the dreary and oppressive realities of their everyday lives” (1976: 294).

There is also a simpler explanation for the popularity of rioting, which probably supplemented and occasionally sublimated other reasons. Perhaps faction riots occurred at regular intervals and were popular because they represented a chance for the young men involved in them to engage in intense physical competition, which we might call sport. Organized personal athletic competition for the average individual was virtually nonexistent in the sixth-century Byzantine world. A riot provided an outlet where a young man could best an opponent in competition, either by pummeling him into submission in a fight or by successfully vandalizing more buildings than his fellows. In addition to this aspect of personal competition, a riot that generally pitted Blue partisans against Green partisans would provide a strong sense of camaraderie for the participants, allowing them to feel like part of a team. The opportunity for personal athletic achievement and team spirit – what more could one ask for in a sport?

This thesis has quite a bit of support in the sources. The authors of the period who provide the vast majority of our evidence are highly critical of the faction partisans and their activities, but in their critiques they conveniently reveal something of the motives of the partisans. As Procopius rather stuffily notes, “many young men now poured in to join the ranks of this team [The Blues], men who had never before shown an interest in its activities but were drawn to it now by the prospect of power and insolence coupled with impunity” (Procopius Secret History 7.23, trans. A. Kaldellis). For Procopius’s “power” and “insolence,” a more sympathetic author might have chosen “victory” and “competition.” Even the critics of the partisans understood some of the urges that underlay their violent actions in riots.

Procopius highlights the importance of competition in the violent activities of the partisans when he explains that while the Blues committed great crimes under Justinian, the most militant of the Greens were also “constantly busy with crimes,” in order to keep up with the Blues (Procopius Secret History 7.2–4). Agathias is also aware of the competition among partisans and especially between the two major faction colors. He scathingly remarks of the partisans that they were “men whose fanatical and headstrong daring confined itself to stirring up civil strife and to supporting one color against the other, but who in real emergencies were cowardly and effeminate” (Agathias The Histories 5.14.4, trans. J. Frendo). Thus the historian understood that the partisans wanted to pride themselves on their success in competition and their daring, but he refused to give them this recognition and instead mocked them for not being brave in a truly dangerous situation, by which he presumably means actual war.

The most interesting evidence for the desire of athletic competition and camaraderie among the rioting partisans comes from our sole source who admits that he used to belong to their number. The historian Menander has already been mentioned, but it is worthwhile to quote in full his description of his former life: “I therefore neglected my career for the disgraceful life of an idle layabout. My interests were the gang fights of the colors, the chariot-races and the pantomimes, and I even entered the wrestling ring. I sailed with such folly that I not only lost my shirt, but also my good sense and all my decency” (Menander Fragment 1, trans. R. Blockley). As befits a more mature man who now has a career and is expected to be above the rambunctious life of a partisan, Menander begins by making clear that his former life was disgraceful. His list of interests is, however, quite revealing about the mindset of the young men who were the partisans in his day. The very first interest he lists is the gang fights of the colors, which says something about the perceived importance of the violence in the riots. Not only does he emphasize the violence, but he is careful to mention the camaraderie of being in a “gang” at the same time. His fascination with the chariot races and the pantomimes is of course nothing unusual as many Byzantines who were not faction partisans were quite obsessed with the spectacles of the hippodrome and theater. Finally, Menander confesses to wrestling, one of our few references to the sport in all of the sixth century. That he mentions a passion for wrestling again suggests an interest in personal physical competition that was no doubt also expressed in the “gang fights of the colors.”

If it is accepted that the young men who were the partisans of the Blue and Green factions instigated some riots because of desire for sport and camaraderie, then it becomes easy to explain why the riots were so closely linked to the spectacles of the theater and hippodrome.8 These spectacles provided the event and location where people could gather together. Once they had arrived and witnessed the pantomimes performing in the theater or the chariots racing in the hippodrome, the most rabid fans, the young partisans of each faction, were driven almost to hysteria by the excitement of the spectacle. As Cameron has noted, the chariot races became extremely important to spectators in the way that critical soccer games bring out passionate spectators in the modern world (Cameron 1976: 293–4). It is not hard to imagine that this passion, when combined with the fact that the spectators had just witnessed a physical competition in the hippodrome, might drive them to triumphantly seek sport themselves. With little in the way of organized outlets for this desire, and with the high emotion that comes with passionate engagement with a spectacle, it is not surprising that the situation often exploded into a fight between the partisans (the most passionate fans) that could then easily ignite a riot. Indeed, this is exactly how the November 561 faction riot in Constantinople unfolded. In the excitement of the spectacle of the chariot races, the Green partisans attacked the Blues, the Blues invaded the seats of the Greens, and when the emperor tried to separate the warring factions with his guards, the fight exploded into a general riot that spread throughout the city (Theophanes Chronographia 235–6).

In the sixth-century Byzantine Empire, spectacle, sport, riot, chanting, and government were all intimately linked. As we have seen, sometime in the late fifth century the imperial government assumed both ownership and administration of the public spectacles of the theater and hippodrome. The success of the rowdiest partisans of the Blues and Greens in leading chants in both hippodromes and theaters led, in the sixth century, to their co-optation as well. The emperors simply could not pass up the chance to utilize these skills that could, when put to the right uses, strengthen and reaffirm their popularity.

By using the partisans to chant for them, however, the emperors were obliged to turn something of a blind eye to their more mischievous side. These partisans, being young men who, at least according to Menander, did not have much better to do, were not only rabid fans of the theater and hippodrome, but also had a strong passion to participate in sport themselves. On many occasions the outlet they chose for this passion was rioting. The disturbance of a riot allowed them to engage in direct physical competition with other young men, and fighting with other partisans of their color provided a sense of team camaraderie. The emperors tolerated this behavior as long as the partisans were mostly interested in fighting each other and only found this to be a serious issue when they united to riot against the government. While there were many reasons to riot, from religious complaints to economic and political issues, the fascination of the young fans of chariot racing with sport and competition should not be discarded as a contributing factor in many riots of the period.

After the sixth century chariot racing declined in the Byzantine world generally, in large part because it had become intimately connected to government finances. The Byzantine government experienced significant setbacks in the seventh century with the Persian War and the subsequent Arab invasions. The resulting financial difficulties probably led to the disappearance of racing in provincial cities, which we cease to hear about in the seventh century. However, chariot racing and the racing factions of the colors definitely survived in Constantinople in diminished form until at least the twelfth century (Cameron 1976: 308). No doubt the imperial government made this a priority because of the opportunity the races provided for the emperor to speak directly to the people and for the people to acclaim the emperor and his policies. Even so, in the twelfth century the Comnenian emperors moved to the palace at Blachernae, farther away from the hippodrome, and, being increasingly influenced by the West, they turned to more distinctly medieval entertainments such as jousts. Thus the final decline of the spectacle of chariot racing in the Byzantine world may be traced to a gradual change of tastes in the High Medieval period. By this time the exuberant faction riots of the sixth century had long since faded away, but for a time in their heyday they had provided an important outlet, not just for economic, political, or religious pressures, but also for the passion for spectacle and sport.

NOTES

1 All dates are CE unless otherwise indicated.

2 On Byzantine individual sports, for which we are much more poorly informed than the public spectacles discussed in this essay, see Ducellier 1980 and Karpozilos and Cutler 1991. The relevant sources are discussed in detail in Koukoules 1948–57: vol. 3: 81–147.

3 On the decline of Greek athletics, see Kyle 2007: 345–6 as well as Downey 1939; Weiler 2004; and Winter 1998. On the decline of the spectacles associated with the Roman arena (gladiatorial combats and beast hunts), see Dunkle 2008: 201–6, 241–4 and Roueché 2008 as well as Cameron 1973: 22–30;1976: 215–18; Ville 1960; and Wiedemann 1992: 128–64.

4 The most popular racing teams of the sixth century were the Blues and Greens, and this was apparently a tradition that stretched back to the Early Imperial period (31 BCE–476 CE). The Whites and Reds were secondary or minor teams, which were managed by and usually paired with the Blues and Greens, respectively. While the Whites and Reds had some adherents, these fans were very much in the minority. See Cameron 1976: 50–6.

5 The Kathisma was connected to the Great Palace by a spiral staircase, access to which was controlled by bronze doors that could be securely bolted. This feature was employed during the Nika Riot of 532 to prevent rioters from gaining access to the palace.

6 The key primary sources for the Nika Riot are John Malalas 473–6; Procopius History of the Wars 1.24.7–54; Chronicon Paschale 620–9; and Marcellinus Comes a.532. The best modern account of the Nika Riot is Greatrex 1997. For a brief overview of the event, see Kaegi 1991.

7 In fact, the role of the faction partisans in cheering the emperor became increasingly formalized into imperial ceremony in the seventh century and beyond. Green and Blue partisans continued to lead formal acclamations of the emperors throughout the middle Byzantine period. See McCormick 1986: 220–7.

8 Of course, it would be a dramatic oversimplification to say that all Byzantine riots started for the simple joy of the competition and sport inherent in the act of rioting. The Byzantines of the sixth century rioted for all sorts of reasons that had little to do with sport. There were very serious ecclesiastical riots in the reign of Anastasius, for instance in 512 when a crowd rampaged around Constantinople to protest the emperor’s religious policy (Greatrex 1997: 62). However, some riots, especially those connected to the Blue and Green factions, probably had young men’s desire for competition as their catalyst, and even riots that started for other reasons might be joined by these young men who loved rioting for its own sake.

REFERENCES

Bassett, S. 2004. The Urban Image of Late Antique Constantinople. New York.

Blockley, R. C., ed. 1985. The History of Menander the Guardsman: Introductory Essay, Text, Translation and Historiographical Notes. Liverpool.

Cameron, A. 1973. Porphyrius the Charioteer. Oxford.

Cameron, A. 1976. Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium. Oxford.

Cartledge, P. 2009. Ancient Greece: A History in Eleven Cities. Oxford.

Coakley, J. and E. Dunning, eds. 2000. Handbook of Sports Studies. Los Angeles.

Croke, B., ed. 1995. The Chronicle of Marcellinus: A Translation and Commentary. Sydney.

Croke, B. 2005. “Justinian’s Constantinople.” In M. Maas, ed., 60–86.

Crow, J. 2008. “Archaeology.” In E. Jeffreys, ed., 47–58.

Crow, J. 2010. “Archaeology.” In L. James, ed., 291–300.

Dagron, G. 1984. Naissance d’une capitale: Constantinople et ses institutions de 330 à 451. 2nd ed. Paris.

Downey, G. 1939. “The Olympic Games of Antioch in the Fourth Century A.D.” Transactions of the American Philological Association 70: 428–38.

Ducellier, A. 1980. “Jeux et sports a Byzance.” Dossiers de l’archéologie 45: 83–7.

Dunkle, R. 2008. Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Harlow, UK.

Easterling, P. and E. Hall, eds. 2002. Greek and Roman Actors: Aspects of an Ancient Profession. Cambridge.

Greatrex, G. 1997. “The Nika Riot: A Reappraisal.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 117: 60–86.

Guilland, R. 1969. Études de topographie de Constantinople byzantine. 2 vols. Berlin.

Haarer, F. 2010. “Writing Histories of Byzantium: The Historiography of Byzantine History.” In L. James, ed., 9–22.

Holum, K. 2005. “The Classical City in the Sixth Century: Survival and Transformation.” In M. Maas, ed., 87–112.

Humphrey, J. H. 1986. Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. Berkeley.

James, L., ed. 2010. A Companion to Byzantium. Malden, MA.

Jeffreys, E., ed. 2008. The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Oxford.

Jeffreys, E., M. Jeffreys, R. Scott, et al., eds. 1986. The Chronicle of John Malalas. Melbourne.

Jones, A. H. M. 1964. The Later Roman Empire, 284–602: A Social Economic and Administrative Survey. 2 vols. Norman, OK.

Kaegi, W. 1991. “Nika Revolt.” In A. Kazhdan, ed. 2: 1473.

Kaldellis, A. 2004. Procopius of Caesarea: Tyranny, History, and Philosophy at the End of Antiquity. Philadelphia.

Kaldellis, A., ed. 2010. The Secret History [of Procopius] with Related Texts. Indianapolis.

Karpozilos, A. and A. Cutler. 1991. “Sports.” In A. Kazhdan, ed. 1, 1939–40.

Kazhdan, A., ed. 1991. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. 3 vols. New York.

Koukoules, P. 1948–57. Byzantinon bios kai politismos. 6 vols. Athens.

Kyle, D. 2007. Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, MA.

Maas, M., ed. 2005. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge.

Magdalino, P. 2007. Studies on the History and Topography of Byzantine Constantinople. Aldershot, UK.

Magdalino, P. 2010. “Byzantium = Constantinople.” In L. James, ed., 43–54.

Mango, C. 1981. “Daily Life in Byzantium.” Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik 31: 337–53.

Mango, C. 1985. Le développement urbain de Constantinople, IVe-VIIe siècles. Paris.

Mango, C. 1991. “Constantinople.” In A. Kazhdan, ed. 1: 508–12.

Mango, C., A. Kazhdan, and A. Cutler. 1991. “Hippodromes.” In A. Kazhdan, ed. 2: 934–6.

McCormick, M. 1986. Eternal Victory: Triumphal Rulership in Late Antiquity, Byzantium, and the Early Medieval West. Cambridge.

Puchner, W. 2002. “Acting in the Byzantine Theatre: Evidence and Problems.” In P. Easterling and E. Hall, eds., 304–24.

Roueché, C. 2008. “Entertainments, Theatre, and Hippodrome.” In E. Jeffreys, ed., 677–84.

Tougher, S. 2010. “Having Fun in Byzantium.” In L. James, ed., 135–46.

Treadgold, W. 1997. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford.

Ville, G. 1960. “Les jeux de gladiateurs dans l’empire Chrétien.” Mélanges d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’École Française de Rome 72: 273–335.

Webb, R. 2008. Demons and Dancers: Performance in Late Antiquity. Cambridge, MA.

Weiler, I. 2004. “Theodosius I. und die Olympischen Spiele.” Nikephoros 17: 53–75.

Wiedemann, T. 1992. Emperors and Gladiators. London.

Winter, E. 1998. “Die Stellung der frühen Christen zur Agonistik.” Stadion 24: 13–29.

Young, K. 2000. “Sport and Violence.” In J. Coakley and E. Dunning, eds., 382–407.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

The essays collected in Jeffreys 2008: 232–94 offer a compact overview of the political history of the Byzantine Empire. For a longer, general guide to Byzantine history that puts together the whole period in accessible format, see Treadgold 1997. The still authoritative work of Jones 1964 offers a detailed analysis of Byzantine government and society in the sixth century. The essays collected in Maas 2005 survey the Byzantine world in the time of Justinian.

For a brief introduction to the written sources for Byzantine history, see Haarer 2010. On Procopius in particular, see Kaldellis 2004 and his recent edition of the Secret History (2010). On Byzantine archaeology, see Crow 2008 or Crow 2010. The articles collected in Jeffreys 2008 provide an overview of and introduction to scholarly study of the Byzantine world.

There is no current book-length study of Byzantine sport and spectacle, but brief surveys can be found Mango 1981; Roueché 2008; and Tougher 2010. Puchner 2002 is a good introduction to Byzantine theater; for a book-length study see Webb 2008.

For a very brief survey of the urban development of Constantinople, see Mango 1991. There is an array of longer works on that same subject, including Bassett 2004; Guilland 1969; Dagron 1984; Magdalino 2007 and 2010; and Mango 1985. Croke 2005 and Holum 2005 focus specifically on Constantinople in the time of Justinian. Basic information on the hippodrome in Constantinople can be found in Mango, Kazhdan, and Cutler 1991. For more detailed work on that same subject, see Dagron 1984: 320–47 and Guilland 1969: vol. 1: 369–595. The standard study of Roman circuses remains Humphrey 1986, which, however, does not discuss Constantinople in any detail.

For years there was a substantial bibliography on the Blues and Greens of the hippodromes that sought to cast them in the role of popular dissenters against Byzantine government. Cameron 1976 fully refuted the previous hypotheses of generations of historians and showed that the Blue and Green partisans were above all passionate sports fans, and his work on the subject remains essential. For a more specific review of the popularity of charioteers, especially Porphyrius, the greatest of all the charioteers of the sixth century, see Cameron 1973. On the history and logistics of chariot racing in the Roman world before the fourth century CE, see Chapter 33.

Kaegi 1991 gives basic information about the Nika Riot. The best modern treatment of that event is Greatrex 1997, and his article is also useful for understanding riots and disturbances in the sixth century more generally. There has been a great deal of modern scholarship on the causes of violence among sport spectators. A good introduction to that scholarship can be found in Young 2000. On the relationship between emperor and populace as played out in the hippodrome, see Cameron 1976: 157–92.

These secondary works are more than enough to provide an introduction to the topic, after which primary sources may be more profitably read to gain direct understanding of spectacle, sport, and riot in the Byzantine world. See especially John Malalas, in convenient English translation in Jeffreys, Jeffreys, Scott, et al. 1986; Marcellinus Comes, translation by Croke 1995; and Menander Protector, translation by Blockley 1985.