Barrett Wendell Frontispiece

Photogravure with autograph signature

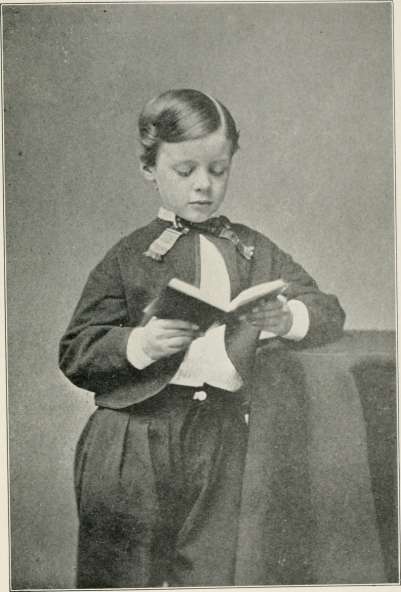

Barrett Wendell at about Eight (1863)

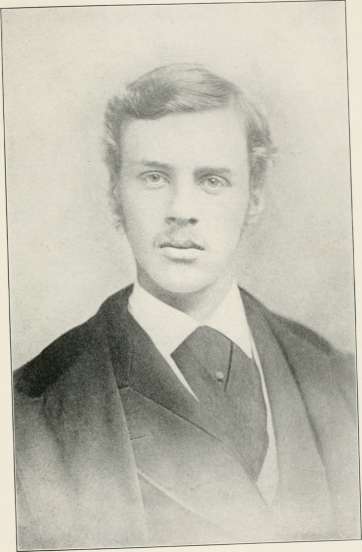

Barrett Wendell at about Seventeen (1872) .

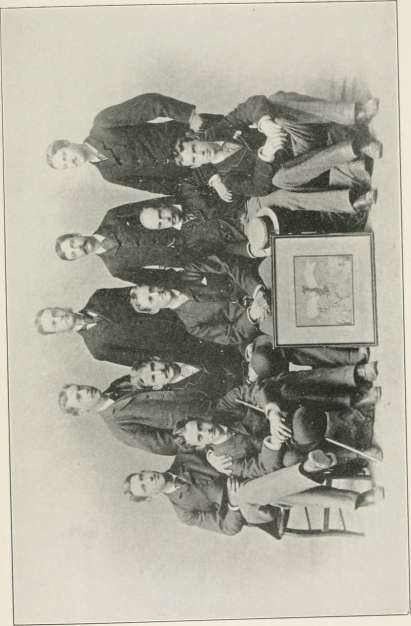

The "Lampoon" Board, 1877

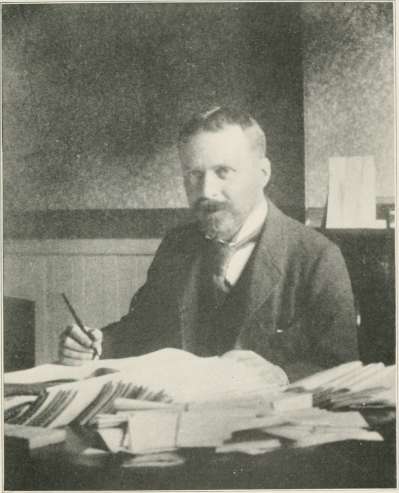

Barrett Wendell at Thirty-Five, in "Grays 18"

Barrett Wendell in "Ralegh in Guiana" .

The Wendell Bookplate

Official Notice of the Naming of "Salle Barrett-Wendell"

"Le Professeur Americain, M. Barrett-Wendell". 160

"Uncle Blunt," with Autograph Christmas Greetings

Autographed Menu at Dinner of Chinese Princes

Barrett Wendell and His First Grandchild

The Jacob Wendell House, Portsmouth, New

Hampshire 294

12

18

24 42

82

118

132

ibS 223 228

BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

INTRODUCTORY

Nearly thirty years after Barrett Wendell published his biography of Cotton Mather, he had occasion to write to a friend who had recently read the book with pleasure. Touching, in the course of the letter, upon what this early piece of work had taught him, he stated a theory of biography in general which his own biographer — if one who intends rather to act as an editor of letters may so be called — seizes upon as a statement not only sound in itself but also peculiarly applicable to the undertaking now invitingly, if somewhat bewilderingly, at hand. Thus he wrote: —

What I learned first, and most lastingly, is that whoever would tell the truth about any man must be, in the literal sense, his apologist. I do not mean that one should make apologies, or indeed write history as Mather did, to emphasize his own opinion. I mean that the first and perhaps the only duty of an honest biographer is, so far as may be, to set forth the man of whom he writes as that man saw himself, and to explain him on his own terms. Then judgment may best be left to those who read.

"To set forth the man of whom he writes as that man saw himself," to explain Barrett Wendell "on his own terms" — there hes the challenge. In the memoir of Wendell which his college classmate and lifelong friend. President Lowell, of Harvard University, prepared for the Massachusetts Historical Society, these significant words are found: "James Russell Lowell said of Words-

4 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

worth that he was two men, and this Is, perhaps, peculiarly the case with men of letters. It was true of Barrett Wendell. There was the real man, and what he thought himself to be; and the former was the larger of the two." There will be many occasions in the pages that follow to bear these words in mind. With them the other true words, written soon after his death, may well be joined: "A certain playful exaggeration of speech, born of his innate detestation of pedantry, often tended to obscure the sound common-sense which underlay his most decided opinions; but those who knew him best did not take long to recognize the simplicity, unselfishness, and high sense of honor, which formed the basis of his character."

Accepting the task of presenting Barrett Wendell as he saw himself, his biographer, then, would have the reader constantly aware that what the subject of this book really was, and what he thought himself and wished others to think him, were frequently at variance. Throughout his life, which covered the time when dual, and even multiple, personalities were becoming objects of special scrutiny, he was appearing in the guises — sometimes disguises — which made him the "character" he was; yet, with all his propensity to the astonishing utterances which seemed to delight him in proportion to their capacity to make his hearers **sit up," he never succeeded in blinding those who really knew him to the essential "simplicity, unselfishness, and high sense of honor" which were his salient personal traits.

It is no wonder that confusion sometimes arose. A letter written to Barrett Wendell in 1906 by a graduate of Harvard then teaching history at Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, relates a significant incident: —

"The recent discovery here of a man who thought George Eliot was President of Harvard, found an added interest in the answer made by a man of the same class

on my American History exam paper, which may be of interest to you. The man has been well drilled in English, in which your name is frequently mentioned, and writes:— 'The Abolition movement increased ... by the orations and agitations of such men as Wm. Lloyd Garrison,

Barrett Henry Ward Beecher, and Barrott Wendell Phillipo.'

"You will note he hesitated, but that you finally received the credit."

Nothing could have given Wendell himself more amusement than to find himself bracketed with the abolitionists. If he had lived in Boston — at least as an older man — at the time when Garrison was making himself peculiarly obnoxious to the more conservative elements of society, he would probably have joined the "mob of gentlemen" who tried to hang the reformer. If he had lived in Boston before the Revolution, it would have been entirely in keeping with the role of his maturer years to ally himself with the Tories, as a defender of the established order. But in whatever century or circumstances his incarnation might have fallen, he would still have been the same faithful, penetrating student and interpreter of letters and life, as he saw their interrelations, the same warm-hearted human being, often misunderstood, — partly, it may be, because he did not by any means always understand himself or greatly care that others should see beneath the contradictory surface, — the same constant exponent of all the loyalties which most nearly concern a man's life.

I

BACKGROUND, BOYHOOD, AND YOUTH

1855-1874

Barrett Wendell was born at 41 West Cedar Street, Boston, August 23, 1855, the eldest of the four sons of Jacob Wendell and Mary Bertodi (Barrett) Wendell. To **explain him on his own terms" it is as necessary to record his ancestry as to relate the experiences of his own existence, for he was intensely aware of the background which he shared with New Englanders of his own kind. In his books — notably the Literary History of America — he constantly spoke of Americans of "the better sort," meaning those upon whom the advantages of breeding and education had bestowed a position of social superiority less obvious to-day than it was in the three American centuries that have gone before. Conspicuously possessed of the historic sense, and therefore much given to identifying a living past with a living present, he brought to the past, as it concerned his own inheritances, a frankly personal interest. It would have been an affectation of a sort quite foreign to him to make any pretense to the contrary. Democracy, in the latest meanings of the word, made but a scant appeal to him. He was fond of using the word ''gentleman," and prepared to accept equally the privileges and the responsibilities implied in the term.

Nearing the end of his life, Barrett Wendell wrote, in 1918, for his children, a memoir of his father, Jacob Wendell, the opening pages of which present the family history with a detail significant of its meaning to him. Those to whom it will mean much less may read the passage with a cursory eye. It runs as follows: —

BACKGROUND, BOYHOOD, AND YOUTH 7

My family was of Dutch origin. The first of them in this country. Evert Jansen Wendel, came from Emden, in East Friesland, to New York, about 1640, when some twenty-five years of age; his widowed mother was then living in a village called Upleward, where she died in the year 1657. In New York, Evert Jansen married Susanna du Trieux, who was probably descended from a Gascon Protestant, recorded as having taken refuge in Holland after condemnation by the Parliament of Bordeaux in the reign of Charles IX. Evert Jansen soon moved to Albany, where he passed the rest of his long life. There, in 1656, he was made ruling elder of the church, in honor of which dignity he had painted in one of the windows a probably assumed coat-of-arms, complacently borne by his descendants ever since. His eldest son, John, married Elizabeth, daughter of Abraham Staats, of Albany; flourished as a trader with Indians; was once mayor of Albany, — I think in Leisler's time, — and died rather prematurely, in 1691, leaving considerable landed property and ten or eleven children. His widow subsequently married John Schuyler, by whom she became the mother of the "American lady" recorded by Mrs. Grant of Laggan, and grandmother of the Revolutionary general, Philip Schuyler. Abraham Wendell was sent in boyhood to New York, where he lived for more than forty years, a merchant and a magistrate, of genially convivial habit and frequent carelessness of obligation. His wife was Catherine, daughter of Teinis and Catherine (Van Brugh) Dekey, through whom the family became kinsfolk of certain Bayards, Livingstons, and other remembered names. Meanwhile, Jacob Wendell, the youngest brother of Abraham, and in every sense a substantial man, had moved to Boston, where he flourished until after 1760, marrying an Oliver and becoming ancestor of Mr. Wendell Phillips and Dr. Holmes.

As early as 1714, he persuaded his brother Abraham to entrust his eldest son, John, to his care, convinced that educational opportunity in Boston was better than in New York. Though this John never entered Harvard College, after all, he lived comfortably in Boston from the age of eleven until his death, in 1762, at fifty-nine. He was convivial, like his father, he became a

8 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

partner in his uncle's business, he was once in command of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery, and he married Elizabeth, daughter of the third Edmund Quincy, of Braintree. Her elder brother, the fourth Edmund Quincy, was father of Mrs. John Hancock; her younger brother, Josiah, was the ancestor of that line which preserved the distinction of the name throughout the nineteenth century;her younger sister, Dorothy, married Edward Jackson, and their descendants, under the names of Jackson, Lee, Higginson, Holmes, and more, continue to this day the most sturdy traditions of ancestral Massachusetts.

The eldest surviving son of John and Elizabeth (Quincy) Wendell, who bore his father's name, was born in Boston, in 1731. He took his degree at Harvard in 1750, and soon went to Portsmouth, where he married a Wentworth, cousin of Benning Wentworth, Governor of New Hampshire. There he lived all his life, a lawyer of speculative disposition, much concerned with the development of the unsettled regions of New Hampshire and Vermont, and patriarchally prolific. His second wife, who was akin to his first, was Dorothy, daughter of Henry Sherburne of Portsmouth. By the two he had some twenty children. My grandfather, Jacob Wendell, born in-1788, was his youngest surviving son. By that time, the family fortunes were pretty well ruined.

This record of family origin therefore becomes significant. My grandfather was akin to many notable families not only in New Hampshire but in both Massachusetts and New York as well. His circumstances, however, were those of the conventional poor boy, with his own way to make. He did his best to do so, meanwhile cherishing ancestral traditions with a fervor which he transmitted to his children. The War of 1812 seems to have brought him his first prosperity. He was successful in privateering ventures; and by 1816, when twenty-eight years old, he found himself in condition to marry. His wife was Mehitable, only child of Mark Rogers of Portsmouth; her father was first cousin, on the mother's side, of Sir John Wentworth, last royal governor of New Hampshire, and traced his descent, through the Reverend Nathanial Rogers of Portsmouth, John Rogers, President of Harvard, whose wife, born Denison,

BACKGROUND, BOYHOOD, AND YOUTH 9

was grand-daughter of Thomas Dudley, and the Reverend Nathaniel Rogers of Ipswich, to the redoubtable Puritan divine, the Reverend John Rogers of Dedham in Essex, who died there the year when Harvard College was founded. Mark Rogers, however, had died young and poor. At the time of her marriage, the fortunes of my grandmother's family were as far from prosperous as those of the Wendells.

The next twelve years had a different story. My grandfather was engaged not only in shipping but in an attempt to establish on the Piscataqua such manufactures as were then founding the fortunes of the Merrimac. By the time of my father's birth, he was more than well-to-do and his affairs promised a fortune ample enough to restore the family to its traditional dignity. Two years later, he was completely ruined. The manufacturing venture proved beyond his resources. Of all his property he retained only the house where he lived; and that, for years, was heavily encumbered. He survived until 1865; but, though he never lost the personal respect won in his prosperous days, he was a broken man. I can clearly remember him — a small man, slight of figure, baldish but with a shock of strong, dark hair, with a tinge of chestnut which queerly contrasted with the white beard on his cheeks and under his chin. Pie was very quiet in manner, yet alert; he had a contagiously hearty laugh, never loud; and all his children loved him dearly.

My father, Jacob, was born on July 24, 1826. My father's earliest memories were of actual poverty. For a while the family could not afford a servant. In consequence, he sometimes had to get up before daylight, split wood, light fires from a tinder-box, and drive the cow to its pasture, a mile or more away, before breakfast and school. His school was good, however.

Accordingly, in the late summer of 1843, when a little past his seventeenth birthday, he secured some small employment in Boston where he literally knew no human being, and started out in search of fortune. His reward came; after some years in the employ of J. C. Howe & Co., selling agents for some of the principal cotton and woollen mills in New England, he was admitted to the firm as a junior partner, in 1853 or 1854. The business relations thus began lasted through all the rest of his

lo BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

life. He had taken about ten years to make good; and he was about twenty-eight years old.

Once secure of something like a reasonable income, my father, on October 24, 1854, married Mary Bertodi Barrett, under conditions which may fairly be called surprisingly happy. What is more, though neither he nor my mother was blessed with tranquil placidity of temper, nor ever quite ignored the inevitable annoyances of daily existence, they loved each other as dearly and as simply at the end of their forty-four years together as they had at the beginning.

They had met at Mr. Coolidge's church, when my mother was still a young girl. When Mr. Ripley's exodus to Brook Farm had threatened to break the church to pieces, one of the few men who stuck staunchly by the wreck and most helped to bring her safe to port was my grandfather, Nathaniel Augustus Barrett, then about forty years old. His grandfather, who had been a considerable man of business in Boston a century before, had been ruined by the Revolution. His father, the youngest of a large family whose few remaining letters show engaging traces of eighteenth-century pleasantry, had not married until well past the age of forty-five; his wife, a Newport Brown, was twenty-two years his junior. She had died with her fifth child, in 1802, when my grandfather was only two years old; and in 1810, when he was only ten, his father had died in turn, leaving four children, a very modest property, and some admirable family portraits, four of which are now in my possession. So, though related to many well-to-do people in both Massachusetts and Rhode Island, the little family was remarkably lonely; for their own cousins in Massachusetts were mostly old enough to be their parents, and as they lived in that part of Braintree now called Quincy, they had never seen much of their Boston relations.

My grandmother was Sally, fourth daughter and sixth of the nineteen children of John and Esther (Goldthwaite) Dorr, of Boston. The Dorrs came from Roxbury, where they had -been respectable citizens for some generations; their fortune was based on trade in furs with China, after 1790, in more or less intimate relations with Mr. John Jacob As tor. As a family

BACKGROUND, BOYHOOD, AND YOUTH ii

they were not intellectually powerful, nor unusually strong in character; but they were remarkably handsome, and all of them whom I remember had an extraordinary air of personal distinction. In the matter of character, too, my grandmother's father, John Dorr, seems to have been exceptional; he was extremely self-willed and dominant; yet his children not only respected and rather timidly feared him, but were genuinely fond of him. He died a month or so before I was born.

The memoir of Jacob Wendell from which this passage is taken does not record the fact that when Barrett Wendell was only eight years old, in 1863, his father's business, which had caused frequent visits to New York, led to the removal of his family from Boston to that city, where he became the representative of his firm. His characteristics have been summarized by President Lowell: "A quiet retiring man without the brilliance of his son, he had business capacity, sterling integrity, and commanded the confidence and respect of those who met him. Not himself a scholar, he believed in the value of scholarship, and of his own motion established a foundation for the highest scholar in the freshman class at Harvard College." Much of the value of his son's memoir of him lies in the self-revelations of its author. The following passage, for example, shows forth the Barrett Wendell of childhood as he saw himself in advancing years: —

As for me, for nearly four years an only child, and on my mother's side an only grandchild, and so perhaps fairly well spoilt before my memory begins, I must have been a rather disturbing puzzle to them both — as well as to my not naturally amiable self. So far as I can now discern, I was in one sense a good child — neither mischievous nor vicious, fairly conscientious and perhaps unusually pure of impulse. On the other hand, my nervous system was always a bit erratic — I can trace the trouble now through my father and his mother to hers, who had a startling experience of interrupted personality about 1800; I was morbidly self-conscious and pettily ill-tempered; I

12 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

disliked physical exercise; my most nearly favorite pastime — I seldom got absorbingly interested in anything — was the writing of far from poetic or imaginative plays. The first which I remember completing was composed v/hen I was eight years old. It was clearly founded on the libretto oiLucia di Lammer-moor, which I had once been taken to hear; it got along all right to the very end — when I discovered with dismay that one character, named Sally, had somehow survived; so with what then seemed to me inspiration, I added some such words as: "Enter Sally, who looks about her, and says,'I die,'and dies." Harmless as this literary propensity may have been, it was not quite intelligible to parents whose own preoccupations, apart from domesticity, were mostly concerned with matters of business or religion, and who assumed — quite sensibly — that normal children ought to like playing out of doors. And I never consoled them by delight in religious exercises. To this day I detest hymns — except the Dies Ira; and I was never graced with the engaging vice of pretending to like, for the gratification of others, anything which has excited my displeasure.

A letter which Barrett Wendell, not quite six years old, wrote (June 27, 1861) to his uncle, George Wendell, came to light when its writer was nearing sixty. It was a child's request for the building of a toy "sailing vessel, steamer, or schooner." His desires were definite: "I wish it to be about middle size and very perfect. If I have to pay you, in your answer to this you can tell me how much you want, but as you are my uncle and say that you do not need any pay, it will be most convenient for me. What do you think about the times?" His own thoughts appear in statements about troops he had seen in Boston, before they went South. Commenting upon the letter, in 1912, when he acknowledged its receipt from his cousin, Arthur R. Wendell, he recalled the pleasant summers of his childhood passed with his family at West Needham — now Wellesley — Massachusetts, and remarked of himself, ** I must have been a funny little prig at five years old.

Barrett Wendell at about Eight (1863)

BACKGROUND, BOYHOOD, AND YOUTH 13

That I was dreadfully self-conscious, and therefore far from happy in personal feeling, I am sure. It took me thirty years at least to get an objective view of anything." The autobiographic pages of the memoir already drawn upon contain another illuminating passage. It relates to a visit which Barrett Wendell, not quite eight years old, paid to New York with his father and mother, apparently shortly before their final removal from Boston in 1863. He had then never been further from Boston than Portsmouth, and never anywhere in a steamboat. "I was vastly impressed," he writes, "by the importance of the journey, which revealed to me my lifelong taste for travel"; and he proceeds:—"

New York I found interesting but disconcerting. I have always been over-sensitive to the solitude of strangers in a great city; and even then New York was comparatively metropolitan. It still kept, to be sure, what now seem unimaginable traces of its Dutch origin; the little hand-carts of the ash-men and scavengers, for example, were drawn by dogs harnessed to the axle, and there was distinctly specialized street-cries — that of strawberries, with its shrill prolongation of the final syllable still echoes in my ears. The older houses, too, traces of which even now linger about Washington Square, had such spacious stolidity that to call their "stoops" steps would have been barbarous. At that time, besides, business still lurked downtown. Union Square, with its bronze equestrian Washington in one corner, was a shady, fenced, oval park surrounded by substantial brick dwellings of the better sort. Madison Square, where the Worth monument already kept an otherwise extinct memory safe behind an iron fence of sheathed swords, was at once more or less impressive; it was enclosed in shabby wooden palings painted a dingy brown, but the houses about it had risen in what I then supposed the supreme glory of brown-stone, and on the corner of 23d Street reposed in all its white marble dignity the solid Fifth Avenue Hotel, unaltered to the eye until more than a generation later they pulled it down. In

T4 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

a small two-story structure, I think, wooden, where the Flat-iron building has long replaced it, was a bookshop, subsequently fascinating to me from the fact that its bibulous proprietor a few years later got into newspaper notoriety by shooting a now forgotten man of letters for undue sympathy with his wife. Fifth Avenue itself started, as I think it starts to this day, in the guise of Washington Square; but almost from 14th Street, blooming into brownstone fronts — as like one another as eggs. It seemed utterly secure from the intrusion of trade.

It was all very splendid; there was something depressingly monotonous, though, in the unbroken vistas of the rectangular streets, and something inhuman in the fact that they were not named but numbered. Compared with Boston, I can now see, it was surging with growth, which means incessant change; and change I have never found instantly sympathetic. At any rate, the nervous effect of it on small me must have filled my parents with dismay; for I vividly remember sitting down on a curbstone in 30th Street one evening and loudly bawling, because very sensibly they would not take me with them to Wallack's, at that time the most fashionable of American theatres. To do them justice, they delayed their start until they had condemned me to punitive bed, and made sure that I was miserably there. I soon went to sleep. I was given to understand the next morning that they had greatly enjoyed the play, which had been " too old " for me.

As Barrett Wendell's first memories of New York, which he never came to like, were closely knit with those of his father, so were his first memories of Europe, which he came to love. The following paragraph from the memoir should therefore be read at this point: —

The summer of 1868, now just fifty years ago, long remained the most delightful I could remember. Exactly why my father decided to take his first vacation from business I do not know. Very likely, our shaven, serene, jocose Doctor Crane had advised a long rest; and very possibly he had thought my mother, too, in need of relief from domestic monotony. At

BACKGROUND, BOYHOOD, AND YOUTH 15

any rate, so far as I knew, they rather suddenly decided to go to Europe, and take me with them. Then my wonder-year of three months began. I can describe it no better than by saying that, although I knew little of Longfellow, I saw Longfellow's Europe — which still seems to me the most purely beautiful of all. My readiness for it, I rather think, had been preparing all my short life, for I cannot remember a time when my Aunt Sarah Barrett was not eagerly willing to tell me inexhaustible stories and legends of the Old World we all came from. The charm of Europe — its beauty, its variety, its fathomless humanity, its immemorial habit of life, its boundless wealth of historic and fantastic tradition, glorious fine art — is really there; and no one ever felt this charm more genuinely than I, even at the age of twelve. The evil of Europe, its sins, its crimes, its baseness, is really there too; but somehow they left me untouched. At worst, they were the fleeting shadows which made clearer the beautiful outlines of what seemed to me — as they seemed to Longfellow and his time — the true features. It was a dream world, suddenly real for a little while.

An old bit of memory rises. At home I thought theatregoing the height of earthly delight; in Paris, one evening, I heard someone say that he was going to the theatre, and found myself indignantly surprised that anybody should so waste time when Europe was there to enjoy.

Learning thus early that "Europe was there to enjoy," and profiting greatly from his own early enjoyment of it, Barrett Wendell was meanwhile undergoing more formal instruction in New York. There is an amusing memento of one of the private schools he attended in the form of a letter, written before he was nine years old, and addressed to "Mr. Sanford, 204 5th Ave., N. Y." In the painstaking script of early boyhood it reads: —

,, c New York, Feb. 26th, 1869

Mr. Sanford ' ^

Dear Sir, — You wanted us to give you our different opinions about gentlemen, and how to distinguish them from other persons.

16 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

I think that any one can be a gentleman if he tries to be.

Gentlemen are not always to be judged by their manners. Lord Byron once said that he once had his pocket picked by the most gentlemanly person he ever met with.

Once in the country while we were taking tea, a man with a sword in his hand walked into our yard. We were surprised because we did not know him. Father and Uncle Frank went out to meet him, and Uncle Frank asked him what kind of a sword he had, and he handed it to him. He proved to be a man named Lynch. He was not a gentleman. Gentlemen are judged by their actions and not by their manners, always, as I said before. Gentlemanly actions and manners arise from a good heart. That man who picked Lord Byron's pocket had only much civility.

This is my opinion of Gentlemen.

Your pupil,

Barrett Wendell

The "man named Lynch," intruding upon the domestic scene, armed with a sword, and the insouciance of "Uncle Frank" in asking what kind of sword it was, suggest a pleasing element of imagination in a child whose heart, with respect to gentlemen, was evidently in the right place. A suggestive bit of evidence that it remained there is found in a maturer reference to gentlemen in Wendell's discussion of the variable meaning of words, in his English Composition: —

What does a man mean, for example, who asserts that another is or is not a gentleman? To one the question turns on clothes; to another on social position gauged by the subtle standards of fashion; to another on birth; to another on manners; to another on those still more subtle things, the feelings which go to make up character; to another still on a combination of some or all of these things. Last winter a superannuated fisherman died in a little Yankee village. He was rough enough in aspect to delight a painter; if he could read and write it was all he could do. But there was about the man a certain dignity and self-respect which made him at ease with whoever spoke to him.

BACKGROUND, BOYHOOD, AND YOUTH 17

which made whoever spoke to him at ease with him. I have heard few more fitting epitaphs than a phrase used by a college friend of mine who knew the old fellow as well as I: "What a gentleman he was!" But one who heard this alone would never have guessed that it applied to an uncouth old figure, not over-clean, that until a few months ago was visibly trudging about the paths of our New England coast.

Of the schooling which immediately preceded Barrett Wendell's admission to Harvard College, he has himself written in the memoir of his father. After mentioning his "nervous over-sensitiveness," he says: —

It was thought best that I should no longer be exposed to the vexatious discipline of a large school. So, after, a short period of private tuition by my mother's cousin John Adams, I joined a small class which he was preparing for college. He had taken what used to be the parlors of a pleasant old brick house on the Fourth Avenue side of Union Square, near 17th Street; and there I resorted daily, with Sam and Arthur Sherwood, and John du Fais — all three editors of the Harvard Lampoon when I was — and a few more. Yet he was not only a first-rate coach for examinations; he actually could manage to teach more than I ever quite believed that he knew. Under him, for one thing instead of copying the /Eneid^ as a punitive task, I read every line of it and of the Bucolics and the Georgics too. Though he may not much have cared for his classics, he recognized that they were literature.

In considering the boyhood which preceded Barrett Wendell's maturity, the notably significant point is that he appears clearly to have derived more from his informal than from his formal instruction. That he was far from robust in his physical and nervous equipment, that his father was able and ready to deal with this condition by supplementing his schooling with much travel, and that the boy had the wit and the character to make the most of the opportunities thus afforded — these facts provide the true link between his boyhood and his maturity.

18 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

The remarkably careful and competent diaries which he set himself to keeping, even in his most youthful jour-neyings, bear witness to this process of self-improvement. Journals of sightseeing, particularly of the young, are the most tiresome things in the world to quote, and young Wendell's shall not be quoted here. But his European diaries of the summer of 1868, when he was thirteen, and of 1871, when he was sixteen, are none the less extraordinary documents. They reveal to an uncommon degree, not only a capacity for close observation but also an appreciation of the significance of historical, artistic, and literary associations. Here was a notable foundation for future building. Here, too, is a clear suggestion that in his own early practice of daily writing he discovered the value of the "daily theme" as the exercise in English composition with which his work as a teacher was peculiarly associated. It is pleasant to think of what he might himself have done in later life by extending to the length of a daily theme the brief record of his visit to the Blarney Stone: — "I contented myself with touching it with Mr. Hitchcock's umbrella and then kissing that." His pupils might then have accounted for his chariness of meaningless praise.

In addition to the journals of travel there are documents of self-improvement in the shape of lurid manuscript plays, under such titles as "Raymond of Caen," "Redwing the Pirate," and "The Moor's Revenge." The most ambitious of them, "The Oubliette, a Story of the Black Forest," written in the year following the summer travels of 1868, bears an obvious relation to the diary-page recording a visit to the Alte Schloss near Baden-Baden. It should be mentioned merely in token of the fact that what the boy was seeing was both extending his knowledge and feeding his imagination, an endowment with which these crude juvenilia show at least that he was liberally equipped.

Of the summer travels of 1871 there is a characteristic

BARRErr Wendell at about Seventeen (1872)

BACKGROUND, BOYHOOD, AND YOUTH 19

reminiscence in a letter written by Barrett Wendell in 1917, apropos of the Reverend Dr. Edward A.Washburn, rector of Calvary Church, New York: —

In '71 he took me abroad with him for three or four months. By that time he was a "rueful Christian," but the best of fellows and the wisest of old friends. He taught me on principle that one should never open a botde that won't keep, without finishing it; and, dear old boy, never ordered more than a pint between us. On one thirsty occasion I insisted on a quart; he stuck to his half pint, made me drink the rest, and put me to bed. There was never better lesson for a youngster.

To the success of the summer as a whole the final page of the diary bears enthusiastic witness. It has, besides, in its self-appraisal, an autobiographic value which warrants its quotation:

So ended the pleasantest journey I have ever taken, and I very much doubt if I shall ever enjoy one so much again. I was just at the right age to be enthusiastic over what I saw, without being too critical — to see all the beauties and hardly any of the impurities of the lands I visited. And I can feel too how much older and more mature I have grown in many ways since I left home. I really think that mentally — and physically too for that matter, for I have not felt so strong for several years — I was a different Barrett Wendell who sailed away in June.

Well, those three months have wrought a change in me that will never be undone; and besides their efect^ every memory of them is perfectly delightful. I am inclined to think that, live as long as I may, I shall never look back to any other period of my life with half the pleasure with which I shall remember this perfect summer of 1871.

In the following year young Wendell was admitted to Harvard College, a freshman in the Class of 1876. This, however, proved an untimely start, and after about six months his fragile health brought his first connection with the University to a premature end. The result of this

20 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

break in his studies was in reality an important contribution to his equipment for the continuous pursuit of his college course which began in the autumn of 1874 with the Class of 1877. In the memoir of his father, already so freely drawn upon, his enriching experiences of 1873 and 1874 are summarized in his own words: —

A recurrence, in April if I remember, of my probably hysterical paralysis had sent me invalid home, where medical advice had forbidden study and recommended open air for some time to come. We passed the summer in a cottage at that part of Swampscott called Beach Bluff, the name of the pleasant and hospitable house of my grandmother Barrett's cousins, the Addison Childs, who then owned the whole neighborhood.

The following year was therefore probably the most important in my life. My New York friend, George Allen, the nephew of Doctor Bellows, had also been out of condition, and had been made purser on the Pacific Mail liner Colima, bound without passengers for San Francisco by way of the Straits of Magellan. He managed to arrange that I should be taken along, and thus have a voyage of six or eight weeks. This was to be supplemented by a voyage across the Pacific, and so around the world. We left New York about the first of October. The Colima broke her propeller somewhere off the coast of Brazil. We put into Rio de Janeiro for repairs; and there, having found conditions at sea other than had been expected, — the captain, for one thing, had tried to bully me into signing over to him a letter of credit for five hundred pounds, — I took myself into my own hands, and went to my beloved Europe.

There I travelled alone for nine or ten months; I visited southern Spain, — with an excursion to Tangiers and Tetuan, I went on to Malta, — in which voyage I accidentally met my dearest of English friends. Sir Robert White-Thomson, who died at eighty-seven, only a few months ago.^ By February I

^ The name of this friend, first as Colonel Thomson, then as Sir Robert White-Thomson, will frequently recur in the ensuing pages. For about forty years, from the late seventies till the end of 1917, shortly before Sir Robert's death, Wendell maintained a steadfast correspondence with him. Sir Robert preserved the letters from Wendell, bound in two volumes, from 1879 to 1912, and carefully arranged thereafter. When

BACKGROUND, BOYHOOD, AND YOUTH 21

had got to Rome, where I stayed for weeks, absorbing the delights I later tried to set forth in my first book. The Duchess Emilia. I passed most of May in Paris. Thence I started on an indefinite summer journey northward, in the course of which I went up the whole length of the Gulf of Bothnia, and saw the midnight sun from the top of Ava Saxa, on the Arctic Circle, and subsequently drove across Scandinavia, and made an excursion to St. Petersburg and Moscow, coming back by way of Warsaw and Berlin. I reached England in time to make my first visit to Sir Robert White-Thomson — then still Colonel Thomson — at Broomford in Devon, and another with his wife's parents, Sir Henry and Lady Ferguson-Davie, at their greater Devonshire house of Creedy. And finally I returned home, in mid-September, by the last side-wheel steamship — the Scotia — which ever carried passengers across the Atlantic, and reentered Harvard with the Class of 1877.

The young traveller's journal of this wanderjahr is no more to be quoted than its predecessors, but its many pages abound in convincing evidence that an American youth, rapidly maturing, and inalienably American at heart, was educating himself to become, in a measure quite uncommon then or since, a genuine citizen of the larger world. This he did become, and in so doing grew to occupy a place that was quite his own among American teachers, thinkers, and writers.

If the temptation to quote must be resisted, there are a few pages in the journal of this period which may at least be paraphrased. They are sharply, even physically, separated from all the other pages by having been cut out of the book in which they were written and enclosed in an envelope marked "Not to be opened except by Barrett

Wendell went to England, as youth and man, a visit to Sir Robert at Broomford Manor, Exbourne, Devon, served periodically to cement the friendship, which grew to include the families of both friends. Sir Robert's eldest son was the late Remington Walter White-Thomson, master and head of a house at Eton. Younger sons were Leonard Jauncey White-Thomson, now Bishop of Ely, and Brigadier-General Sir Hugh Davie White-Thomson. His only daughter, Ada, is the Hon. Mrs. Edward St. Aubyn.

22 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

Wendell." In a somewhat maturer handwriting their author inscribed the words, "otherwise to be burned," and "over." On the back of the envelope he wrote: "By way of avoiding melodramatic legends, in case this packet should fall into the hands of an imaginative person, I shall state that the contents are certain leaves cut out of my journal, written while in Malta in January, 1874. They are of rather a religious nature, and so ridiculous that I did not dare leave them where anybody could get at them; and I keep them only with the hope of having a good laugh over them some time or other."

A biographer, finding the envelope already opened, owes it both to his subject and to his readers to touch upon these pages. They relate, with transparent honesty and admirably straightforward and thoughtful expression, the revolt of a sensitive youth of eighteen against the traditional Deity of New England theology, seen even through the tempered austerities of the Anglican forms in which the youth was reared; his acknowledgment of a God of his childhood, "a dear, kind, gentle, loving God, to whom I could always go for aid and consolation"; the impossibility of reconciling the public and the private Deity; his scorn of the hypocrisy he would have to show in any pretense to this end, and of his contemporaries ruled by no such scruples; his abhorrence of forcing his disbelief or belief, In which he was not happy, on others; his realization that his mind was "still in its teens," and that the pages represented no settled opinions.

Fifty years after they were written they do represent an Intellectual and spiritual candor. In which the later workings of Barrett Wendell's mind and spirit had their roots.

COLLEGE AND LAW STUDY

1874-1880

If the two preceding chapters have accomplished their purpose, the reader will have seen that Barrett Wendell came to his college and law studies with a preparation for them quite unlike that of most x'\merican youths of his own or later days. The impression he made upon his undergraduate contemporaries at Harvard is clearly preserved in President Lowell's memoir of him^: —

"At college he stood high in his studies, though not among those at the top of his class, for his interest was rather literary than learned, and he had no ambition for rank as such. He was strongly individual, striking out for himself instead of following the conventional track. Partly perhaps from delicate health, partly from his experience in travel, he was more mature than his fellows. At this time also he appeared to them somewhat radical, or rather iconoclastic, in temperament. That was a period when American taste was very crude, uncongenial to people who, like himself, were familiar with the more mellow traditions of an older world; and a revolt was beginning against the tone of thought which they termed 'Philistine' and Xhromo-civillzed.' One outlet for his energy he found in the group of men who founded the Lampoon^ said at the time to be the best product of student life in the University, and certainly the most original. To that publication he contributed freely while in college and the Law School."

1 Proceedingsy Massachusetts Historical Society, Dec. 1921

24 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

The early volumes of the Lampoon^ begun In February 1876 by a small group of students which included several of Barrett Wendell's closest friends, may be scrutinized both as social documents and for what they reveal in Wendell himself. The paper owed its origin to the refusal of the Advocate^ another undergraduate journal, to print an ironic picture and communication on the Art Club by R. W. Curtis, an Advocate editor, and J. T. Wheelwright, each of the Class of 1876. They joined to themselves Wheelwright's brother, E. M. Wheelwright, later a distinguished architect, Samuel and A. M. Sherwood, who had been schoolmates of Wendell's in New York, E. S. Martin, of Wendell's college class, 1877, now the wise and witty editor of Lije^ and, as business editor, W. S. Otis, then of the sophomore class.

The first issue of the Lampoon was dated February 10, 1876. The Art Club skit seems mild enough, after nearly half a century, yet fairly prophetic in its tone of much that the Lampoon was to print in later years. It might have happened last week, for example, that an imaginary archaeologist should write in a letter from Crete: "I have a rare piece of frieze from an ancient ice-chest." But in general the pages of the early Lampoons^ both in text and in picture, speak for a past remote enough to be taking on an historic aspect. The current crudities of American life, especially as revealed at Harvard College, became fruitful objects of humorous scorn, offset by admiration of Eastlake furniture, London clothing, and all the contemporary symbols of " the correct." Young men wearing incredibly long belted ulsters, with Incredibly large plaids and Incredibly winged wing-collars, stalk through the pages of the journal. With its second volume, beginning October, 1876, that admirable Illustrator, F. G. Attwood, afterwards Identified with Lije^ became a contributor of drawings and an editor. At the same time Barrett

i^

Cj

1^

I H

—. '»j

is

1^

Wendell, who had contributed to the second and ninth numbers of the first volume, joined the staff. From that time forth, through his senior year, his year in the Law School, and the two following years of his law studies in New York and Boston, he remained a contributor and intermittently an editor.

The tone of his contributions is illuminating. They reveal a somewhat world-weary young man, both consciously and unconsciously clever, evidently fond of saying smart, "snobbish," and — to the more conventionally minded — irritating things, indulging himself freely in the venerable cynicism of youth, and obviously enjoying it all to the full. While still a junior in college, he imagines a young graduate spending his summer vacation with his family, and exclaiming, "I felt as if I had on a tight coat — I never dared to let myself out, for fear of making a split." Out of college himself he produces, in "A Want Supplied," an amusing outline of a "Boston peerage," prophetic of his own interest in genealogical matters. A paragraph from "Some Considerations concerning Shop and the Talk Thereof," which appeared during his year in the Harvard Law School, is characteristic enough to be quoted: —

Shop, in short, is the thing we devote our lives to. We come into the world in the shape of eight or nine pounds of red, squirming, squalling, ugly flesh, with no apparent object beyond squirming and squalling. We squirm and squall with infantile frankness for some years in pretty much the same fashion, whether we be high or low, rich or poor, European, Asiatic, African, or American. By and by we grow old enough to be circumspect. We exercise our powerful will. We make ourselves squirm more or less obstreperously, in the fashion most suited to our taste or our condition. We teach ourselves to squall as a habit on a single note. In short, unless we are happy enough to have our minds made up for us, we make up our minds as to what we shall be. We settle down into our shops; we talk about them with delicious unconsciousness that

26 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

everybody has not as much interest in them as ourselves. We laugh at the shop-talk of more enterprising shopmen; and because we do not happen to do a very thriving business, we amuse ourselves with the idea that we are not in trade.

By no means a negligible bit of youthful social philosophy! Many others might be cited to exhibit a genuine though sometimes a rather desperate interest in life. The Lampoon served Wendell an excellent purpose as a medium for characteristic self-expression. It also bore a close relation to his lifelong friendships, for among its editors were his academic seniors, Robert Grant, of the Class of 1873, and Frederic Jesup Stimson, of the Class of 1876, each destined to distinction in letters and affairs, each close to Wendell through all his years. Of his many contributions to the Lajnpoon, none other has endured so long at Harvard as his invention of the generic student-name of "Hollis Holworthy."

Since Harvard College became Barrett Wendell's "shop," it is worth while to pause a moment more and look at him as an undergraduate. Not at all given to athletics, — which then as now afforded a passport to general prominence, — marked by peculiarities of manner and temperament which at a time of life when human beings are most ruled by conventions set him apart from his fellows, he made the social and intellectual affiliations pertaining to the larger clubs, a place on the editorial staff of the Crimson before his association with the Lampoon, and membership in the now defunct *'0. K.," a society of "literary" proclivities; but attained the distinction neither of undergraduate election to Phi Beta Kappa nor of membership in one of the more rigorously selective social clubs. Near the end of his sophomore year, in May 1875, prompted whether by the lure of congenial companionship or by military ardor, he joined the First Corps of Cadets in Boston. In this relation Wendell

must have come nearer than in any other to participation in vigorous physical exercise. During his young manhood an injury to his back brought on a lameness, observable only to the most watchful, yet sufficient to cause his habitual use of a cane in walking. Throughout his life he was seldom far from the limits of his physical and nervous strength.

Of all his teachers at Harvard there was none whose influence appears to have counted more permanently with him than James Russell Lowell, the discursive scholar, also a man of the world, who cared much more for the spirit than for the letter of the books which formed the subjects of his teaching. In a little volume, Stelligeri and Other Essays Concerniyjg America^ published by Wendell in 1893, and named for "those that bear the stars" (the asterisks denoting death in the old Latin catalogues of Harvard graduates), there is an essay on "Mr. Lowell as a Teacher," which made its first, anonymous appearance in Scribners Magazine for November 1891. In this paper Wendell tells of the prompting that came to him in his junior year, through a lecture of Norton's, to read Dante under Lowell. He knew not a word of Italian, and was firmly resolved to waste no more time on elementary grammar. Nevertheless, he applied to Lowell for admission to his course. His plea was kindly, though quizzically, heard; "and finally," says Wendell, "with a gesture that I remember as very like a stretch, [he] told me to come into the course and see what I could do with Dante." In the paragraph that ensues it is not fantastic to find a clue to much of Wendell's own later teaching: —

To that time my experience of academic teaching had led me to the belief that the only way to study a classic text in any language was to scrutinize every syllable with a care undisturbed by consideration of any more of the context than was grammatically related to it. Any real reading I had done,

28 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

I had had to do without a teacher. Mr. Lowell never gave us less than a canto to read; and often gave us two or three. He never, from the beginning, bothered us with a particle of linguistic irrelevance. Here before us was a great poem — a lasting expression of what human life had meant to a human being, dead and gone these five centuries. Let us try, as best we might, to see what life had meant to this man; let us see what relation his experience, great and small, bore to ours; and, now and then, let us pause for a moment to notice how wonderfully beautiful his expression of this experience was. Let us read, as sympathetically as we could make ourselves read, the words of one who was as much a man as we, only vastly greater in his knowledge of wisdom and beauty. That was the spirit of Mr. Lowell's teaching. It opened to some of us a new world. In a month, I could read Dante better than I ever learned to read Greek, or Latin, or German.

Thus it was not only what Barrett Wendell learned about Dante from Lowell, — and through that he became a lifelong reader and lover of Dante, — but also what he learned about teaching, that made this course of study a truly formative influence. He must have learned also the value of a close personal relation between teacher and pupil, for his remembrances of encounters with Lowell in his study at Elmwood are recorded with warm appreciation. When the Class of 1877 graduated, Lowell stepped at once into public office as United States Minister to Spain, but not until the class, torn with dissensions over its senior elections and threatened with the loss of all its Class Day pleasures, availed of the departing professor's hospitality in the use of Elmwood and its grounds for the time-honored festival. The Smith Professor of the French and Spanish Languages and Literatures and Professor of Belles-Lettres had provided the later Professor of English with a standard of relationships, individual and collective, to be applied in what was then a distant future.

For the three years that followed Wendell's graduation

from Harvard College he was a student of law, and not at all a happy one. He began his legal studies through no desire on his own part to become a lawyer but — the prospect of a business career being abhorrent to him — in conformity with his father's wish that he should prepare himself for some useful employment. In 1877-78 he attended the Harvard Law School; in 1878-79 he was a student in the New York law office of Anderson and How-land; in 1879-80 in the Boston office of Shattuck, Holmes (now Mr. Justice Holmes of the United States Supreme Court), and Munroe. At the end of these three years he presented himself in Boston for examination for the bar — and failed. "At that time," President Lowell has written, "he remarked that while all his friends whose judgment he respected thought he ought not to accept a defeat, but try again, he did not himself see why he should do so. Nor did he; and he was right. His friends had not appreciated capacities not fully revealed, or the future that lay before him in quite a different line."

For the two years between his graduation from Harvard College (1877) and his engagement in marriage (May 1879) to Edith Greenough of Quincy, Massachusetts, Barrett Wendell suffered a frankly miserable existence. The winter of 1878-79, spent in a New York law office, was perhaps the worst time of all. But all the available letters of this period — and a considerable number, addressed to F. J. Stimson, have been preserved — reveal clearly the writer's deeply discouraged outlook upon the world: this is equally true whether they are written from New York or from the Isles of Shoals, where his family was then wont to spend the summer, or from Florida, which he visited In the spring of 1879 In company with another lifelong friend, John Templeman Coolidge. These letters to Mr. Stimson are, however, so charged with personal flavor and so significant as documents of

30 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

sensitive youth, discouraged to the point of despair, yet unknowingly on the very threshold of satisfying achievement, that some passages from them may profitably be cited. Since many of them are but partially dated, their chronological sequence cannot be guaranteed.

8 East 38TH Street, New York

... I can find no words to express the dulness of life here; and the devil of it is that I am yielding to it completely. In Gath I am becoming a Philistine. Nunc de me tacendum.

My cousin Lilly Wendell is staying here — having what she describes as a pleasant time. All I know about it is that I have in no way contributed to her pleasure. The Upham girls dined here the other night. . . . Miss 011a . . . talked about Matthew Arnold, and I became feebly interested in that poet and bought a volume of his effusions. They are horribly pedantic and priggish, to my mind; but the fellow means something and knows what he means. I don't like his way of putting things as a rule, but I understand the things he means to put better than I expected to. I have come across several ideas of my own — not original, but favorite — badly embalmed in artificial poetry, but still recognizable. So on the whole I am rather glad that I bought him — particularly as the book happens to be bound in cloth of a most delightful color — a rich dark peacock blue-green — and is extremely ornamental and correct upon a somewhat chromatic library table.

I am deep in the Divine Comedy again. After all, Dante is the only book which carries me away. I manage to lose myself in the smoky depths of hell for half an hour or so every evening; and I am beginning to incline to the opinion that, whatever my own views may be on the existence of that locality, it is a matter of congratulation that the people of the Old World entertained strong convictions upon the subject. Hell has certainly given me more pleasure during the past two years than Heaven and Earth combined. . . .

8 East 38TH Street, Sunday ... I was greatly amused yesterday at the contrast between

your letter and some remarks addressed to me by the boss. You accused me, as of a crime, of being able, after all, to become excited from time to time. The boss stated with deploring gravity that he had never seen a person of my age who showed so little power of caring for anything. On the whole, I might as well keep on with law; he did n't know that anything else would bore me less; but unless I roused myself to a little more enthusiasm than I at present showed for anything, he did not promise me any great chance of success in life. Then he said some civil things about no need of work and the management of family estates, that were mildly amusing, and our tete-a-tete ended. . . .

49 Nassau St., New York, January 7,1879

Dear Fred, — I have tried with utter lack of success to do the writing you ask for. You can form no idea, in your present Kingsley state of mind, of the utterly ruinous condition of my character. I have lost every atom of self-control I ever had. I am growing duller, and stupider, and weaker, and more of a Philistine every day. I shall not be surprised if you do not answer this note for a dozen reasons. It is rude to write on office paper. It is contemptible to leave Lampy in the lurch after having pledged myself to help him. It is doubly contemptible to see a sane, healthy-looking man of three-and-twenty who ought to be a gentleman, and as a gentleman to have something approaching a respectable amount of character and determination, fading out into a miserable limp paper-doll, which has not even the recommendation of being dressed in the fashion.

Believe me, Fred, I do not know how to help myself. My life is a succession of fits of indignation at my own weakness, and of fits of complete abandon to that weakness, in which I grow weaker and weaker. I will try to do something for you, and for myself; I am beginning to fear — I have been beginning to fear for some years, I believe — that while man proposed that I should be something, God in his infinite wisdom is disposing of me as a mere copyist in a bad hand— with an ultimate view to the fertilization of the soil.

32 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS [/f/ the end of an undated letter from Appledore^ Isles of Shoals]

LA TRISTEZZA DI APPLIDORO Opera Tragica

PERSONE

IMMORTALI

Mr. Barrett Wendell: handsome, accomplished, genial, beautiful, foolish, studious, literary, sentimental, and unhappy.

Mr. : ugly, ponderous, intellectual, appalling, bugbear

pro tern, to B. W.

: musical, smiling, slightly under the influence of liquor.

H. 1. BowDiTCH, M.D.: elderly, dovelike, fresh from an operation on the 1-g of a young woman from parts unknown. Santa Celia: patron goddess of the island.

MORTALI

White men: none.

Miss : dark-eyed. Oriental, voluptuous beauty from New

York. Bad musician, goodish flirt. Slow mother and fast brother.

Miss : jolly, noisy, and at a loss for somebody to flirt with.

La Marchesa di Inferno e Fiamme: sister to the foregoing. Misses Bowditch and Sister, Long, Kate Wendell, Jones, Almy, and Weiss: walking ladies.

DiABOLi POVERi (i.e., cads)

A family named , and a whole lot of people with other

names.

Old women, old men, young women, young men, noisy children, etc., by a large company, which for a wonder is destitute both of accomplishment and talent.

Jacksonville, February 27

. . . No one can know better than I the damning sense of uselessness which saddens the lives of men like you and me when we find ourselves, as we find ourselves too often, with leisure to think and nothing in particular to think about. Life for its own sake is not to us worth living. Whether it be our national dyspepsia, or our unused muscles, or a hateful

fact makes very little difference. To us eating, drinking, living, and breathing — even if we breathe this delicious Florida air — are delights which we shall not be very sorry to say good-bye to. Yet something or other deters us from being the first to speak the farewell word. In my own case, it is half a regard for the feelings of people whose lives I do not help to make happy, and yet who have a certain fondness for me which can be explained upon no rational ground; and half a feeling that it would be a confession of weakness at which men whom I think not so strong as I would laugh. If other people can bear life until its end comes, I ought to be able to bear it too. At any rate, if I can carry through the world these wretched nerves of mine, that quiver with pain at things which make other men's nerves vibrate with pleasure, I can at least feel that I may leave the world without the fear that it will pry into my secrets. As a cynical character in one of my comedies says, "All men are fools. Those only are wise who succeed in concealing their folly." The removal of oneself from the world is a confession of folly which sets all the world which knows us to picking our follies to pieces. We are not allowed to rest in peace without a psychological post-mortem performed by very unskillful doctors. And Heaven grant that when our time for rest comes, it may come at last as peacefully and be as peaceful as our world will let it be. . . .

8 East 38TH Street, [Good] Friday

... I went to Trinity Church this morning with Ned. The great altar, with the white reredos rising behind and a flaming window full of saints and angels above it, was draped in heavy black. A great white cross stood out against the draperies. The church was full of people of every rank in life, standing side by side with that wonderful Christian equality that we see in the old churches of the Old World. And the most glorious floods of solemn music came rolling down the dim Gothic aisles. It was a morning to be remembered for a lifetime. Ned was sorry that he could not sympathize. I did sympathize, and it was all that I could do to help myself from falling on my

34 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

knees when that grim old prig of a gave a benediction

as solemn as a Pope's.

The frame of mind represented in these letters, written chiefly from New York, was obviously due in large measure to imperfect health, uncongenial prospects, and a general lack of incentive to satisfactorily directed effort. Two of these three difficulties vanished with his engagement. The tone of his letters immediately underwent an extraordinary change, the reasons for which are not far to seek. Miss Greenough's father was William Whitwell Greenough, a Boston man of affairs, for many years a resident of Quincy, who enriched the life of his community by a long and valuable service as president of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library. Through her mother, Catherine Scollay (Curtis) Greenough, her New England lineage was identical at points of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with that of Barrett Wendell. To all the congenialities of ancestral and immediate background, there was added that fortunate divergence of temperament upon which the happiness of one so constituted, emotionally, as Wendell may depend.

The more significant passages in Wendell's letters to Stimson in the years between his engagement and his marriage are too intimate for print. To his older English friend. Colonel Robert Thomson, he wrote, apropos of his engagement and his prospects, more appropriately for the present purpose.

Quincy, September 28, 1879

Dear Colonel Thomson, — Your welcome present has just been sent to me from 38th Street, where Mr., Gray left it a few days ago. I am sure that I need not tell you how much it pleased me; and indeed did I feel that there were such a need, I should not know how to do so. I have begun to learn this summer that there are real feelings in the world that conven-

tional expressions were Invented to describe, and yet which they fail to describe for the very reason that they are conventional. And so when I thank you most heartily for your kind remembrance, I am sure that you will understand that I appreciate and value your sympathy in my happiness and your kind hopes for my future.

How soon my future will assume a definite form I cannot yet say. My father does not wish me to be married until I am admitted to the bar; and Miss Greenough is an only daughter and is only twenty years old, so her people are unwilling to lose her; and although I have a hope of being married in the spring, I hardly dare to breathe it abroad and nothing is settled as yet. I have already begun my studies. I read law for four or five hours every day in a Boston office, with one of the most charming men I ever met — young Wendell Holmes, a son of the Autocrat of whom you have probably heard — and a distant kinsman of mine, although I never happened to know him until a few weeks ago. Quincy is so near Boston that I can come out every evening, however; and here I shall stay for a few weeks longer. Then I am going into lodgings in Boston for the winter, I have taken a suite of rooms with my most intimate college friend [F. J. Stimson] and we are looking forward to some delightful evenings over a great wood fire ....

But instead of turning to letters at this point, we may better resort to one of Wendell's own principles of composition and bring this record of his student years to a close with something like a summary of the preceding pages. This is found In his own words, written In the memoir of his father which has already proved its value to the present purpose: —

So in the autumn [of 1877] I returned to Cambridge, and began the study of law. The year was disappointing. Though I have since found that the discipline of legal study strengthened my mental habit for life, the work at the time was both detestable and depressing. An accidental physical fact probably had something to do with this. The muscles of my back have

always been rather weak, so that I habitually walked with a cane ever since I was an undergraduate. The hard chairs of the Law School library therefore combined with the constant need of going to bookshelves and handling heavy volumes to keep me constantly tired. Even now, in consequence, I am aware of instinctive displeasure when I see a book bound in legal calf. The fact that my courtship looked unpromising did not help things; and in the early winter a not serious illness resulted in a permanent scar on one cheek. At the end of the year I did not take the trouble to present myself at the annual examinations, so got no credit for what work I had reluctantly done. Hardly any line of conduct could have been more disconcerting to a parent; yet I do not remember that the letters sent me by my father contained even a syllable of reproach. Instead, he found no fault with my suggestion that I had been devoting myself too long to abstract study, and might possibly find the more responsible duties of studying in an office less repugnant; and he proceeded, with no help on my part, to find a place for me.

My months of professional study in a Nassau Street office gave little relief. The surroundings there, nevertheless, were friendly. The head of the firm, Mr. Henry Anderson, had become, as he always stayed, an affectionately intimate friend of my father; they had met, I believe, as vestrymen of Calvary Church. His wife's friendship with my mother was just as close.

My work in the office was mostly the searching of titles and the indexing, with cross references, of the published reports of the New York courts — the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals. Though an admirable discipline in the matter of accuracy, it was solitary and far from stimulating to the imagination. Some time in February or March I got to a point of nervous depression which I imagined serious. As usual when even the shadow of real trouble appeared, my father was instantly kind, and let me go for two or three weeks to Florida with my college friend, Templeman Coolidge. Called to Boston, not very long after my return, by the funeral of a classmate, I found my personal affairs taking a wonderful turn for the

better, and came home engaged. In every way this happily altered the outlook.

In the frequent and prolonged intervals of my office I read, as conscientiously as I could, the subjects requisite for admission to the Suffolk bar. When the examinations came in April or May, I presented myself. Greatly to my chagrin, I failed to pass them. On general principles, I should have expected my father to be furious, and Mr. Shattuck — whose office had never before produced an unsuccessful candidate — to be resentful. Instead, though both confessed regret, neither spoke an unkind word. Just as if I deserved it, the preparations for my wedding went on. I was married at Quincy, on the first of June, 1880, to Edith Greenough.

The next week my wife and I passed together in the old family home at Portsmouth, which was destined years later to become our own, and where I am writing now. Already fond of it, I had asked Aunt Carry to lend it to me; and, doubtless at my father's suggestion, she had cordially done so, going away for some family visits. I can now see that my wish to begin my new life in his old home touched him deeply; however we might unmeaningly have jarred on one another, our hearts proved at one.

His real wedding present was a letter of credit for five hundred pounds, which gave us three months of travel in Europe. On our return, while we were still staying for a few days in 38th Street, came from a clear sky the telegram which decided my future career. Months before, I had chanced to meet in the street my college teacher of English, Professor Adams Hill. We had hardly come across each other since I graduated. He asked me what I was doing. I told him that I was reading law. He asked whether I liked it; I said no. And on his duly inquiring what kind of job I should prefer, I am said to have answered, "Even yours." Somehow the incident stuck in his memory. So early in October, finding himself in need of some one to read sophomore themes, he proposed my name to President Eliot, who was always fond of experiments with inexperienced teachers. The result was a telegram, inviting me to come on and discuss the matter. It arrived, I think, on

38 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

the evening when Doctor Washburn came to dine, and I saw him for the last time; he died a few months later — some years younger than I am now. The telegram decided my career; it also gratified my father as indicating, for the first time, that somebody thought me conceivably useful. Though I began teaching at Harvard thus fortuitously and with no notion of keeping it up long, and though more than once I came near dropping the work, I was actually on the rolls there as a teacher for thirty-seven years; and a few months before my father died he was gratified by my promotion to a full professorship.

THE YOUNG INSTRUCTOR AND WRITER

1880-1:

Though the year 1880 marks the beginning of Barrett Wendell's definite work in the world, no excuse is needed for having devoted so much space to the years preceding that date: they were the years that determined what he was just as much as what he was not to be. His personal stars in their courses fought against the law and practical affairs quite as clearly as on the side of letters and their pursuit. The obvious means to this end was an academic post, and — for Wendell — at Harvard. His own apprehension of the grounds on which his appeal as a teacher began to be felt, was frankly expressed on an autobiographic page relating to his early years of teaching: "The work at Harvard kept me pretty busy; I did it conscientiously, and my oddities of temper and of manner chanced to interest my pupils." There can be no doubt that his marked individuality counted in his favor.

One who came to know him when he had been teaching only six years out of the thirty-seven devoted primarily to this work may be permitted to recall himi, not as he appeared at any one period, as a younger or an older man, but in the singular unity of impression produced by his personality throughout his life. He stands, then, before the eye of memory, well-proportioned of figure, of moderate height, shapely of head, tawny-bearded, with quick blue eyes, alert and responsive in personal encounter, the man of the world rather than the professor In general appearance. Ready of tongue, addicted to repartee, he expressed himself in a staccato and much-inflected speech

40 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

that was eminently his own — not the utterance of Oxford, yet much more English In its effect than American. Add to this distinctive characteristic such an easily Imltable habit as the twirling of a watch-chain while addressing an audience, and It Is no wonder that Barrett Wendell offered an Irresistible temptation to the mimic In successive college generations.

It Is a sure token of poverty when a college does not possess In Its teaching force one or more "characters," the " taking off" of whom becomes a recognized accomplishment. These are generally the men who Impress themselves most strongly upon the undergraduate. The superficial things about them can be, and are. Imitated with mirthful results. As a rule, however, the personal peculiarities of a teacher are interesting in proportion to his own value as an Instructor and stimulator of youth. The real things, — the fruits of study and thought, the expressions of intellectual and personal friendship, the intimate concern for the welfare of pupils, — these are not objects of mimicry, however they may enhance its appeal. In the case of Barrett Wendell — as many of his letters will show — such realities stood throughout his career at the foundation of his teaching and of its far-spreading Influence.

In October 1885, as in February 1876, almost exactly ten years before, a new periodical came Into existence at Harvard through a secession from the Advocate. This was the Harvard Monthly, in the origin of which Barrett Wendell was even more involved than in that of the Lampoon. An editorial article in the first issue declared, "There can be no doubt that the study of English composition at Harvard has come out of the second and into the first rank of the studies now offered," and referred particularly to Wendell's course, "English XII," started only the year before and already enrolling about a hun-

THE YOUNG INSTRUCTOR AND WRITER 41

dred and fifty men. The purpose of the Monthly was to establish "a magazine which shall contain the best literary work done here at Harvard, and represent the strongest and soberest undergraduate thought." The editor-in-chief of the first volume was Alanson B. Houghton, now United States Ambassador to Germany, and on the editorial board were the late George Rice Carpenter, who became a distinguished professor of English at Columbia, William Morton Fullerton, afterwards Paris correspondent of the London Times^ and George Santayana. Carpenter was the second editor-in-chief; George P. Baker, now professor of dramatic literature at Harvard, the third; and Bernhard Berenson, the fourth. With these men, their colleagues, and their successors, — of whom the maker of this volume happened to be one, — Wendell stood in a stimulating relation of counselor and friend. The Monthly^ an ambitious infant, needed all the help he could give it, in continuance of his sound advice to its parents before its birth, and all this help Wendell gave, without stint. He contributed the first article to its first number — a New England sketch, ** Draper," based directly upon a passage in one of his diaries recording a driving trip with his brother Gordon from New York to Boston in the summer of 1885. His interest in the magazine might indeed have been taken for granted, since the Monthly was merely the student expression of the very concern for letters which Wendell as a teacher had begun to quicken. The immediate result was a publication which after nearly forty years bears with astonishing credit the test of critical examination. No doubt its editors — and perhaps Wendell himself—thought it more remarkable than it really was. What neither they nor he may have realized is that the teachers who throw themselves as heartily into an undergraduate enterprise as Wendell did in this instance are few. Their ultimate reward is suggested by

42 BARRETT WENDELL AND HIS LETTERS

Professor Baker, in his reminiscence of Barrett Wendell, printed in the Harvard Graduates^ Magazine for June 1921:

"Mine was the day when the Harvard Monthly was founded. It might almost be said that Grays 18, the room his name made famous, was its editorial office, for he was intensely interested in the magazine from the first day of its founding. In its second year I never knocked in vain at Grays 18 for counsel as to policy, available undergraduate work, or searching criticism. Immediately after the appearance of each number, at least a postcard and often a detailed letter of criticism would be on my desk. Nothing ever did so much to give me a sense that an art is far greater than any of its servants as Wendell's praise and blame of those successive numbers.'*