Spain Today

Profound upheavals have shattered a status quo in Spanish public affairs that had endured since the country’s return to democracy in the 1970s. A two-party domination of national politics has been split asunder by new parties born of popular anger at corruption and economic crisis; the push for independence in Catalonia has challenged assumptions of Spanish unity; and corruption finally came home to roost at the highest levels in 2018 with the unseating of the conservative Partido Popular (PP; Popular Party) government.

Best on Film

Jamón, jamón (1992) Dark comedy that brought Penélope Cruz and Javier Bardem to prominence.

Todo sobre mi madre (1999) Classic Pedro Almodóvar romp through sex and death.

Ocho apellidos vascos (Spanish Affair; 2014) Hugely successful comedy that takes a sideways glance at Spain and the Basque Country.

Mar adentro (The Sea Inside; 2004) Alejandro Amenabar’s moving study of a Galician quadriplegic (Javier Bardem).

Best in Print

Three Plays (Federico García Lorca) Spain’s greatest playwright’s three great tragedies, about passion and trapped lives, written in the 1930s.

For Whom the Bell Tolls (Ernest Hemingway; 1941) Terse tale of the civil war, full of emotions and Spanish atmosphere.

A Late Dinner: Discovering the Food of Spain (Paul Richardson; 2007) Erudite journey through Spain’s fascinating culinary culture.

Don Quijote (Miguel de Cervantes; 1605) Spain’s best-known novel is a laugh-inducing journey with a lovably deluded knight.

Crisis in Catalonia

Many Catalans have long felt that the centralising tendencies of the Spanish state did not adequately respect their distinct culture, history and traditions. The push for Catalan independence that developed after economic crisis struck Spain in 2008 grew into a direct confrontation with the central government in Madrid, plunging modern democratic Spain into its biggest-ever crisis.

Catalonia is one of Spain’s most prosperous regions, and resentment mounted about the size of its tax contribution to the national exchequer – by most estimates, €8 to €10 billion more per year than it gets back in services. In 2015 an alliance of pro-independence parties, led by Carles Puigdemont, came to power in Catalonia promising to hold a binding referendum on independence. Despite uncompromising opposition from Madrid, and a judgement by Spain’s constitutional court that the referendum would be illegal, it went ahead on 1 October 2017. The Madrid government sent in national police to try to prevent voting at some polling stations, resulting in some violent scenes and injuries. According to the Catalan government, 43% of the electorate voted in the referendum, and 90% of those voted for independence.

In response to the referendum, a wave of support for Spanish national unity swept through much of Spain. Huge, peaceful demonstrations, both for and against independence, took place in Barcelona. On 27 October the Catalan parliament declared Catalonia independent, but the national parliament suspended Catalonia’s regional autonomy and the Catalan parliament with it. A few days later Spain’s attorney-general called for serious charges of rebellion and sedition against Puigdemont and 13 of his (now ex-) ministers; Puigdemont and four of them had slipped off to self-imposed exile in Brussels.

New Catalan elections in December 2017 saw separatist parties win 70 of the 135 seats in the regional parliament, giving them the opportunity to form Catalonia’s new government. But by late March 2018, regional government had still not been restored, since all candidates who had been proposed for its presidency were either abroad (as in the case of Puigdemont) or in pre-trial detention. On 23 March Spain’s supreme court dealt the separatists a new blow by ruling that 25 of them be tried for crimes including rebellion and embezzlement of public funds over their involvement in the referendum, with some facing jail terms of up to 30 years if convicted. Two days later Puigdemont was arrested in Germany, whose courts were due to rule within 60 days on Spain’s request for his extradition.

While Spain’s major political parties had made some noises about possible constitutional reform, the Madrid government was in no mood for any meaningful concessions to the independence movement, perhaps betting that support for it would wane over the coming months and years.

A New Politics

At a national level, Spain’s political spoils had for decades been divided between the left-of-centre PSOE and the conservative PP. In 2015 and 2016, a groundswell of popular anger from the years of economic crisis changed all that, with two new anti-corruption parties – the radical, anti-austerity Podemos (‘We Can’) and the centrist, pro-business Ciudadanos (Citizens) – winning scores of seats in general elections. The PP managed to form a minority government – but this came to a dramatic end in June 2018 when the PP was unseated by a parliamentary vote of no confidence, following a high court judgement in one of numerous long-running corruption cases that have embroiled Spanish political circles. In the so-called Gürtel case, over events which mostly took place in the early 2000s, more than a dozen former PP members were sentenced for taking bribes for government contracts and other crimes, and the judges referred to the party’s involvement with ‘institutionalised corruption’.

The new prime minister, Pedro Sánchez of the PSOE, gave early signals of stability, but with his party holding just 84 of the 350 parliamentary seats and a spectrum of varied allies to keep happy, plenty more twists and turns in the political picture were in the offing.

Economy on the Up

By the end of 2017, unemployment in Spain was down to 16% – there were still 3.7 million people out of work, but this was a big improvement on the depths of the economic crisis five years previously, when joblessness reached 27%. Spain was the fastest-growing large economy in Europe, with tourism, car-making and digital startups all booming. There is still a way to go, and critics say too many of the new jobs are temporary and unstable, but despite the political upheavals Spain’s economic picture is certainly far rosier than just a few years ago.

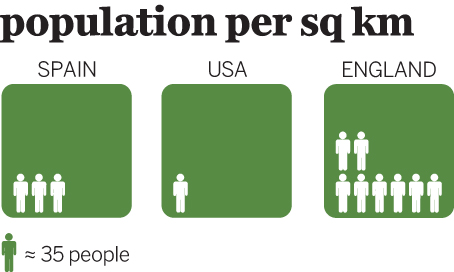

AREA:

505,370 SQ KM

POPULATION:

48.96 MILLION

GDP PER CAPITA:

US$36,400

UNEMPLOYMENT:

16.7%

ANNUAL INFLATION:

2%