2

New Urbanizations

In the early days of gentrification research, gentrification was often understood as a process that involved a ‘back to the city’ movement of people, especially the return of middle-class families who were known to have fled inner city areas in order to pursue a suburban way of life based on automobile culture, single family units and the low prices of suburban land that made such a lifestyle more affordable (although we now know that many of these pioneer gentrifiers came from other inner-city areas rather than having their origin in the suburbs). Despite the extended discussions on the causes and outcomes of gentrification, one fixed variable that has long characterized the landscape of gentrification debates is the association of gentrification with inner-city areas, while suburbanization is linked to urban fringes. This tendency is succinctly captured by Tim Butler (2007b) who summarizes that:

Most accounts…have defined the two processes [gentrification and suburbanization] as spatially specific — either to the inner city (in the case of gentrification) or the city fringe (in the case of suburbanization). The problem is that these accounts are rooted in specific moments of the paired process of industrialization and urbanization that took place in the 19th and 20th centuries.

(p. 762)

To a large extent, the focus of gentrification researchers on inner-city areas can be said to have resulted from the ways in which the new urban phenomenon of gentrification, originally conceptualized by Ruth Glass, contested the modernist understanding of how cities evolved over time through the rise of suburban affluence at the expense of inner-city dereliction and poverty. In other words, gentrification, which is understood as the repopulation of inner-city neighbourhoods by affluent groups through residential rehabilitation at the expense of displacement of working-class residents, questioned the received wisdom long-preached by the Chicago School of urbanism.

Lees, Slater and Wyly (2008) explain the detrimental impacts of the ways in which the Chicago School has incorporated neoclassical economic theories for explaining urban processes. Having emerged in the early twentieth century with the pioneering publication of the book The City, the Chicago School of urbanism provides a modernist perspective on the city, which regards urban conditions as outcomes of rational personal choices based on consumer sovereignty (Dear 2003: 500–2). In particular, the spatial configuration was to take on the form of a series of concentric zones, ‘[b]ased on assumptions that included a uniform land surface, universal access to a single-centred city, free competition for space, and the notion that development would take place outward from a central core’ (Dear 2003: 500). According to the bid-rent theory of land use (see Alonso 1964), suburbanization was explained as the rational outcome of competitive bids by different segments of population, making trade-offs between accessibility and space. That is, suburban neighbourhoods saw the incoming of wealthier families who were in possession of consumption preferences for a more spacious living environment and who had the economic capability to pay for higher transportation costs due to long-distance commuting. In return, inner-city neighbourhoods were understood to have been cramped by poorer families who suffered from high living costs and small and crowded dwelling spaces. Gentrification of inner-city neighbourhoods suggested that the urban evolutionary perspective held by the Chicago School of urbanism was seeing an anomaly, which increasingly commanded its presence in a number of (post-industrial) cities.

The Chicago School of urbanism tried to explain the ‘return of people’ to inner-city areas without eroding its own belief system. Resorting to the continued use of the bid-rent theory of land use, Schill and Nathan (1983), for instance, explained that gentrification can be a rational response of a select group of upper-income families who outbid all other existing groups near the central city, as they happen to ‘value both land and accessibility, and can afford to pay for them both…and outbid all other groups for land close to the urban core’ (p. 15). In this scenario, the remaining task is to explain why and how the selected group of upper-income families has come to display changes to their consumption preferences. To some extent, the faction of gentrification research that focused on the changing characteristics of individual gentrifiers can be said to have been a response to neoclassical studies on changing preferences for consumption (of land and housing) (see Chapter 3).

Location-wise, as suggested at the beginning of this chapter, gentrification has been associated with inner-city areas or the central city. As such, its decades-long debates bear the footprints of the concentric ring model of the Chicago School or modernist thinking about urban development that assumes the presence of singular centrality in urban spatial configuration. Even if we restrictively define gentrification as an inner-city urban process (though this chapter is to go beyond this narrow definition), gentrification and suburbanization are not necessarily ‘a zero sum game either in terms of investment cycles or residential choice’ (Butler 2007b: 762). The two processes may happen simultaneously, for instance, due to the expansion of the middle class itself, (domestic and international) migration that add populations to both the city core and the suburbs, or by means of promoting peripheral development such as science parks and gated communities while also investing in inner-city service industries such as financial districts (see Butler 2007b).

With a renewed understanding of urban development and new theoretical insights into urbanization processes, it may be time to revisit these key assumptions in gentrification research. In this chapter, we try to push further Eric Clark's (2005) call for the ‘order and simplicity of gentrification’, taking into consideration recent debates in critical geography about global suburbanism and planetary or extended urbanization (Keil 2013; Brenner and Schmid 2014; Merrifield 2014). In particular, we pay attention to how urban centrality emerges in multiplicity, going against the modernist assumption of a single core that radiates outwards to conquer rural hinterlands in the process of suburbanization. Andy Merrifield (2014) in his discussion of planetary urbanization refers to the ways in which the centre-periphery relationship is being reproduced across the urban, without being restricted to a singular centrality versus the rest of the urban as the periphery. To a large extent, our approach in this chapter can be said to be a response to this call for removing centre-periphery binary thinking, requiring a more flexible way of conceptualizing how capital reinvestment removes barriers to its operation in the built environment, and hence creates conditions ripe for the class re-making of urban space, including demand creation through speculative activities. Bearing this in mind, we shift our attention to the rest of the world, beyond the usual suspects of gentrification, which presents us with a quite different picture of urbanization and therefore landscape of gentrification.

Refining a concept or stretching it beyond its utility?

Theoretical enquiries by means of constant shifting between abstraction and concrete realities inevitably focus on how changing realities influence the refinement, enrichment or abandonment of original concepts. Gentrification has been no exception. It has gone through many rounds of debate on how it can be understood in, and applied to, a particular space and time other than those associated with its original conceptualization. While it is important to pay attention to the complexity of urban processes influenced by a set of on-going and historical contingencies of economic processes, socio-political relations, cultural norms and regulatory systems, it is equally important to avoid excessive conflation of urban processes by paying attention to both ‘order and simplicity’ (Clark 2005), as we do in our enquiry into the process of gentrification.

The conceptual definition of gentrification has been evolving over time and space, reflecting the expanding epistemological horizon over how the urban is defined and what new trends of urbanization have emerged. Gentrification in its first conceptual appearance was largely referring to the take-over of working-class neighbourhoods by middle-or upper-income households through residential rehabilitation (Glass 1964a). This focus on residential rehabilitation and inner-city location remained for some time. Neil Smith, in his 1982 article on Gentrification and uneven development, defined gentrification as:

the process by which working class residential neighborhoods are rehabilitated by middle class homebuyers, landlords, and professional developers…The term gentrification expresses the obvious class character of the process and for that reason, although it may not be technically a ‘gentry’ that moves in but rather middle class white professionals, it is empirically most realistic.

(pp. 139–40, n. 1)

For quite some time, residential upgrading or rehabilitation remained as a core characteristic of gentrification, and therefore neighbourhood change through demolition and new build development was differentiated from gentrification. Smith (1982) made this ‘theoretical distinction between gentrification and redevelopment’, arguing that the latter ‘involves not rehabilitation of old structures but the construction of new buildings on previously developed land’ (ibid.). For some, the preoccupation with the key characteristics outlined by Ruth Glass (1964a), that is, incremental residential rehabilitation in inner-city working-class neighbourhoods resulting in displacement, has led to overly sensitive approaches to contextualizing gentrification (for example, Maloutas 2011; see a critique of this in the introduction to Lees, Shin and López-Morales 2015). Warning against dogmatic adherence to concepts abstracted out of non-necessary relations, Eric Clark stated in 2005, ‘being necessary for explaining a particular case is different from being a necessary relation basic to the wider process. Central location may be one important cause of the process in some cases, but abstracting this relation to define the process leads to a chaotic conception of the process, arbitrarily lumping together centrality with gentrification’ (p. 259).

Over time, on-going political and economic restructuring altered the terrain within which gentrification unfolded. Gentrification turned out to be no longer confined to a set of core cities in the global North nor did it restrict itself to housing rehabilitation (see Davidson and Lees 2005, 2010). Developmental projects that sought to rewrite urban landscapes became larger, and so did the institutional support systems that made mega-projects possible in a more market-friendly way. Domestic and transnational financial actors also all geared up so that developers, governments and even individual homebuyers could gain a foothold in the investment frenzy. As property-led regeneration became increasingly pivotal to urban policymaking (Healey et al. 1992), urban redevelopment became the norm, organizing buildings and dwellings into a super-bloc to promote area-based clearances and the reconstruction of upmarket commercial and residential premises. Accordingly, Neil Smith revisited his position on this in his 1996 publication The new urban frontier, arguing that it was no longer meaningful to make a distinction between rehabilitation and redevelopment:

Gentrification is no longer about a narrow and quixotic oddity in the housing market but has become the leading residential edge of a much larger endeavor: the class remake of the central urban landscape. It would be anachronistic now to exclude redevelopment from the rubric of gentrification, to assume that the gentrification of the city was restricted to the recovery of an elegant history in the quaint mews and alleys of old cities, rather than bound up with a larger restructuring.

(p. 37)

Five characteristics of urban development influenced the mutation of gentrification, namely ‘the transformed role of the state, penetration by global finance, changing levels of political opposition, geographical dispersal, and the sectoral generalization of gentrification’ (Smith 2002: 441). In this regard, it was inevitable for gentrification to be redefined as:

The investment of CAPITAL at the urban center, which is designed to produce space for a more affluent class of people than currently occupied that space…Gentrification is quintessentially about urban reinvestment. In addition to residential rehabilitation and redevelopment, it now embraces commercial redevelopment and loft conversions (for residence or office) as part of a wider restricting of urban geographical space.

While the definition of gentrification evolved to be more inclusive of redevelopment in addition to rehabilitation, there still remained a central focus on urban centres or inner-city areas, as the two quotes from Neil Smith above clearly show. This focus on inner-city areas or traditional urban cores has continued to dictate the boundary of gentrification debates. For instance, Lees, Slater and Wyly (2008) also define gentrification as ‘the transformation of a working-class or vacant area of the central city into middle-class residential and/or commercial use’ (p. xv; emphasis added); they considered ‘other’ gentrifications, like rural or suburban gentrification to be related but different. In this book, we move the debate on and argue that this focus on inner-city or singular centrality needs to be questioned further. If we retain the class remaking of urban space and the resulting (in)direct displacement of urban inhabitants (both users and occupants) as the core characteristic of gentrification, as Neil Smith's latest definition suggests, and if we are to take into consideration how urbanization unfolds in those places outside of the usual comfort zone of ‘Western’ gentrification, we must question the central city as the hegemonic site of gentrification globally. As early as 2005, Eric Clark suggested that there is no reason to confine gentrification to just inner-city areas, if it is to be defined as capital reinvestment that brings about the transformation of neighbourhood characteristics to accommodate more affluent households.

Gentrification in the context of planetary urbanization

As the remit of gentrification research is extended to urbanization outside of Western European and North American regions, gentrification research travels out of its usual comfort zone. The global South experiences urban development that often exceeds neighbourhood scales. Individual projects gentrifying neighbourhoods and urban spaces may come together to create ‘metropolitan-scale’ gentrification as Shin and Kim's (2015) discussion of the temporal and spatial concentration of urban redevelopment and reconstruction projects in Seoul attests to, a process that can be termed ‘mega-gentrification’ (see Chapter 7). In Rio de Janeiro, without mentioning the word ‘gentrification’, Queiroz Ribeiro (2013) claims that the whole urban system of the city has surrendered, since the early 1990s, to a state-led process of service-oriented economic reshaping to reverse the decline of its post-industrial urban economy. In this case, the policy prescription has rested on large-scale housing formalization and social domestication in favelas, especially those considered as the most dangerous and centrally located.

There are also projects at the regional scale. In India, for example, Goldman (2011) traces the development of a regional development strategy that centres on the Mysore-Bangalore Information Corridor in Karnataka State, which includes the construction of an information corridor, an expressway and several brand new townships. The whole development is expected to displace ‘more than 200,000 rural people’ (Goldman 2011: 566), and to involve land expropriation from villagers, who are compensated poorly, while developers are to benefit from highly elevated ground rents. Rent gap exploitation is at work here (see Chapter 3), in the same manner as it has been carried out in inner-city redevelopment projects, though the process of disinvestment followed by revalorization as discussed by Neil Smith (1979, 1996) has not happened here. Rather it is the expected gains from elevated real estate value, or potential ground rents and the fact that local villagers are rid of their rights to benefit from future development. Indeed, this is the regional blown-up version of what López-Morales (2011) refers to as ‘gentrification by ground-rent dispossession’ with regard to inner-city redevelopment in Santiago de Chile. Can one say this process conforms to gentrification? If yes, it surely goes beyond the imagination of most gentrification scholars and anti-gentrification activists, and at the same time, presents them with an acute understanding that there is a common thread that connects inner-city gentrification in New York City or London with speculative property development on village lands in India or mainland China. If yes, it surely substantiates the point that gentrification is less a certain predefined urban ‘condition’ and more a mutating process of urbanization, in which gentrification-led displacement is nothing more than an outcome of already existing unequal power relations within a society, contributing to the intensification of societal polarization. Gentrification is less about predefined loci, morphological attributes and scales, but much more about a process that depends on the contextual reconfiguration of state policies and embedded class and power relations (see Chapter 3). Furthermore, as Lees Slater and Wyly (2008: 138) have noted with regards to rural gentrification studies, ‘it is the underlying logic of the process of capital accumulation which unites the urban and rural, and the gentrification of both’.

The brief discussions above prompt us to rethink the nature of urbanization and its meaning in the contemporary world. The starting point is the role of real estate in capitalist societies, building upon Henri Lefebvre's and David Harvey's discussions about the ascendancy of the secondary circuit of capital accumulation. In his thought-provoking book, The Urban Revolution (2003), Lefebvre posits:

I would like to highlight the role played by urbanism and more generally real estate (speculation, construction) in neocapitalist society. Real estate functions as a second sector, a circuit that runs parallel to that of industrial production, which serves the nondurable assets market, or at least those that are less durable than buildings…As the principal circuit – current industrial production and the movable property that results – begins to slow down, capital shifts to the second sector, real estate.

( pp. 159–60)

For Lefebvre (2003), the second sector of real estate acts like ‘a buffer’, a shock-absorber so that surplus capital is channelled into it ‘in the event of a depression’ (p. 159). Harvey concurs with this line of analysis, arguing that the capitalist urban process is inherently prone to the over-accumulation crisis in the primary circuit of industrial production, which then calls for the switching of capital flows into the secondary circuit of capital that constitutes fixed asset and consumption fund formation (Harvey 1978). The switching of capital occurs in two dimensions, sectoral switching and geographical switching (Harvey 1978: 112–13). The former includes the capital channelling from one circuit to another, for instance, industrial capital channelled into innovation or real estate. Geographical switching entails the transfer of capital from one locale to another, and is particularly pertinent to investment in the built environment due to its immobile nature. But also the switching of capital from the primary circuit to the secondary one is what characterizes the rapidly developing economies of the global South, as many of their policies and economic agents, without necessarily responding to imperialism, reinforce the uneven development of capital across urbanizing spaces as well as regional and national territories.

While the channelling of capital from the primary circuit of industrial production to the secondary circuit of the built environment was thought to be temporary, to address the over-accumulation crisis in industrial production, Lefebvre posits the possibility of the secondary circuit rising above the primary circuit and becoming permanently dominant, stating that ‘[i]t can even happen that real-estate speculation becomes the principal source for the formation of capital, that is, the realization of surplus value’ (Lefebvre 2003: 160). In developing countries experiencing accelerated urbanization and economic development, the need to expand the capacity of infrastructure and housing construction becomes tantamount to an increase in their capacity of industrial production (see Shin 2014a for discussions on China).

When Lefebvre predicts the coming of an ‘urban revolution’ and hence an ‘urban society’, he is essentially telling us about the global ascendancy of the secondary circuit of capital, especially real estate based on the capitalist logic of accumulation that subordinates industrial production to the built environment. Like the world market for Karl Marx, ‘the urban’ is a vital necessity ‘for the reproduction of capitalism on an expanded scale’ (Merrifield 2013a: 913). Lefebvre initially observes post-industrial urban societies when he argues that the secondary circuit of the built environment has become ‘the mainstay of a global and increasingly planetary urban economy, one of the principal sources of capital investment, and hence over the past 15 to 20 years the medium and product of a worldwide real-estate boom’ (Merrifield 2013a: 914), but with its planetary outreach, the speculative frenzy has also usurped the developing world that sees a greater role for speculative land and housing markets in its urbanization processes. It is in this context that we situate the debates on the rise of global gentrifications (see the concluding chapter in Lees, Shin and López-Morales 2015), or neo-Haussmannization according to Merrifield (2013a) that ‘integrates financial, corporate and state interests, tears into the globe, sequesters land through forcible slum clearance and eminent domain, valorizing it while banishing former residents to the global hinterlands of post-industrial malaise’ (p. 915).

Speculation on real estate has been closely associated with gentrification debates due to its impact on both the production of gentrifiable properties and people's desire to accumulate wealth by investing in real estate properties (see for example, Smith 1996; Ley and Teo 2014). Here, the above Marxist perspective helps us in terms of how the broader structural mechanism of capitalist accumulation and the desire of surplus creation elevates the status of the real estate sector. In Western European and North American countries, the demise of Keynesian welfarism and the rise of neoliberal urbanization have facilitated the hegemonic position of real estate, aided by the financialization of real estate properties, enabling immobile properties to be subject to globalized flexible investment strategies (see Moreno 2013, Weber 2002). In the global South, real estate speculation has also resulted from the pursuit of increasingly mobile capital and professionals, as well as the desire to raise the profile of major urban centres as part of political legitimacy building, often sucking in capital for real estate projects at the expense of more productive uses (see Cain 2014; Goldman 2011; Shin 2014a; Watson 2014). It is in this context, the rise of urbanization at a planetary scale, that we concur with Neil Smith's preposition that the rise of new urbanism in the increasingly neoliberal world has entailed ‘the generalization of gentrification as a global strategy’ (Smith 2002: 437).

The rise of a generalized gentrification across the globe does not, however, necessarily mean that gentrification gets imported in an imperial fashion, although there is an increasing tendency towards cross-border policy mobility that enables the travelling of ‘best practices’ (see Chapter 5). As Shin and Kim (2015) explain in relation to the rise of speculative urbanization in the context of South Korea, gentrification as a class-based strategy to advance capitalist accumulation through the spatial fix may be more endogenous and long-established than critics may have thought. Driven by a capitalist urbanization process that sees the rise of the secondary circuit of real estate in conjunction with the primary circuit of industrial production, land and housing markets become attractive destinations for both household and business investments, eventually producing speculative urban policies that depend heavily on market-driven redevelopment to transform disorderly and substandard (from the perspective of authoritarian state elites) urban spaces into organized, middle- or upper-class oriented ones. This speculative nature of urban transformation entices emerging middle classes as strong advocates of urban redevelopment projects (read gentrification), at the same time as disempowering resistance movements against displacement.

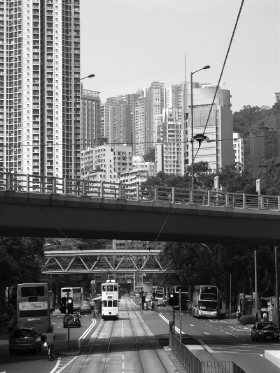

In this regard, as Ley and Teo (2014) have succinctly demonstrated in relation to Hong Kong, gentrification may exist and govern the ways in which urban reinvestment changes the social and spatial landscape in existing built-up areas, even if the process is not explained locally by invoking the label ‘gentrification’ per se. Hong Kong's situation provides an additional dimension in terms of how previous studies of gentrification focused on ‘cultural consumption’ can be merged more synthetically with attention to fundamental economic processes of accumulation (see Figure 2.1). Ley and Teo (2014) refer to the ways in which collective consumption in the form of mass provision of public housing has long been part of urban policymaking in Hong Kong, and explain how such provision of public housing acts as a buffer to the rise of any meaningful resistance against redevelopment. Furthermore, people's aspirations to accumulate property assets, hence the coining of the term, ‘culture of property’ has been legitimizing the city-state's drive for city-wide investment and reinvestment in the built environment. That is, ‘the tenacious culture of property in Hong Kong has obscured the working of a familiar set of class relations in the housing market, relations satisfactorily described by the concept of gentrification, albeit gentrification in a distinctively East Asian idiom’ (Ley and Teo 2014: 1301).

The East Asian experience of speculative urbanization illustrates the importance of the developmental state and their guiding and interventionist role in promoting economic development (and hence their ability to address economic sustenance of the general population to acquire legitimacy for their undemocratic rule). When we shift our attention to a completely different urbanization context such as the Middle East, the underlying logics of capital accumulation and spatial fix through investment in the built environment also provide a landscape amenable to the rise of gentrification, albeit in a Middle-Eastern style (see Chakravarty and Qamhaieh 2015). For instance, Krijnen and De Beukelaer (2015) provide a useful introduction to the situation in Beirut where real estate became an important economic sector in the midst of post-civil war reconstruction in the early 1990s. Low-rise apartment blocks built in the 1950s have been targeted for demolition, to be replaced by high-rise upmarket buildings. The role of civil conflicts and sectarianism, especially in facilitating or confronting gentrification and displacement is pertinent. Politicians engage heavily with the real estate sector, diaspora capital (especially Lebanese expats outside Lebanon working and living in other Middle Eastern countries) buying properties, hence most new flats purchased remain mostly uninhabited. The gentrification is mostly new-build, though some elements of commercial redevelopment through partial rehabilitation have occurred. The Lebanese state, since independence from France in 1943, has never provided welfare; affordable housing provision, if any, occurs through religious or sectarian groups.

Abu Dhabi, along with other UAE cities such as Dubai, has been promoting a spectacular urbanization through mega-projects (see Figure 2.2) financed by its oil money, and enjoys the reputation as ‘a safe haven for investment and an attractive place to live and work’ (Chakravarty and Qamhaieh 2015: 60) for large (transnational) corporations and their employees. Nevertheless, the city suffers from a chronic shortage of rental properties especially for the middle- and low-income expat tenants who do not share the fortunes of those highly skilled expats at the other end of the spectrum. In Abu Dhabi, the small circle of master developers that control most of the real estate infrastructure ‘are all either majority-owned by parastatals or have such close ties to key members of the ruling family that they are effectively under the government's control’ (Davidson 2009: 72). It is also known that stakeholders in real estate corporations are also holding public positions, and there is a blurry boundary between the private sector and the state due to close relationships (see Chakravarty and Qamhaieh 2015). There is a similarity between what happens in Abu Dhabi and elsewhere in the Middle East such as Beirut where there is a stronger fusion between real estate capital and the state, largely due to the fact that (a) Beirut's downtown is depopulated due to the decade-long war; (b) most properties in downtown Beirut were acquired by the developer Solidere, which was established by the former Lebanese prime minister; and therefore, (c) ‘political power and private capital investment were held in the same hands’, creating more amenable conditions for the wholesale redevelopment of downtown Beirut (see Elshahed 2015: 136).

Global suburbanisms and peripheral urban development

More recently, there has been new interest in suburbanization, this time guided by scholarly interests in how suburban space has been governed and is reshaped through investments in land and infrastructure often led by a coalition of domestic and transnational elites but also by endogenous inhabitants who adapt to the new suburbanism. Roger Keil (2013) has proclaimed, ‘[m]uch of what goes for “urbanization” today is not what was seen as such in classical terms of urban extension. Rather, it is now generalized suburbanization’ (p. 9; original emphasis). By claiming ‘suburbanization’, Roger Keil is not so much disputing the proliferation of urbanization at a range of geographical scales (in other words, planetary urbanization) as emphasizing the revelation that peripheral areas outside the traditional urban core are where many investment activities are taking place. That is, ‘much if not most of what counts as urbanization today is actually peripheral’ (Keil 2013: 9). These activities are involving the construction of new-built forms of a diverse nature, ranging from gated communities (neighbourhood scale) to new towns and special economic zones (metropolitan or regional scale).

Selective investment is made in peripheral spaces where the urban meets the rural. Sometimes, leapfrogging takes place to install beachheads of the urban in areas that are predominantly rural by creating zones of exception (Levien 2011; Wu and Zhang 2007). Rural communities become subject to land expropriation and dispossession due to projects that aim to transform such areas into ‘world city’ locations or to host mega-events to raise the profile of host cities or countries (Goldman 2011; Shin 2012). When an entire rural village becomes subject to land dispossession to produce a new township that is designed to attract elites, professionals and the affluent, is this ‘gentrification’? Such urbanization goes beyond the usual geographical scale that gentrification research thus far has attended to, that is, the neighbourhood scale. For instance, in the case of a regional development project to install an IT corridor in Bangalore, India, farmers were forced to sell their lands at a fraction of market-going rates. Another example would be the case of the highly mediatized project of Vila Autódromo (Vainer et al. 2013; Roller 2011) in Rio de Janeiro, located close to the suburban Barra de Tijuca neighbourhood. This case represents one of many similar displacement programmes that have affected thousands of households resulting from a series of investments in Olympic-led infrastructure and mega-transformation of the city (dos Santos Junior and dos Santos 2014). In Goldman's (2011) research, we see the emergence of the IT sector as a beachhead for (justifying) real estate projects, made possible by the joint actions of parastatal agencies, international financial institutions, and transnational policy networks such as international consultancy firms. All these agents and their interests merge together to produce the mega-displacement of villagers whose lands are taken away and villages torn down. The demolition was to clear the way for lucrative real estate projects to build brand new townships as a means to provide homes for national elites and skilled expats. In this process, those dispossessed are rendered vulnerable, while ‘[l]and speculation and active dispossession inside and surrounding the city of Bangalore is the main business of its government today’ (Goldman 2011: 557).

The whole process is a blown-up version of what usually takes place in many new-build gentrification projects that are driven by sub-national government agencies, housing bureaus, (trans)national architectural firms, domestic/global investment capital, and so on. Because compensation is made on the basis of the assessed land value pre-development, the expropriation of villagers' lands in peripheral or rural areas entails the unequal appropriation (dispossession) of ground rents in the form of lost opportunities for villagers and any other previous users of village lands to benefit from the elevated post-development value of village lands. As Goldman (2011) states:

Under the law of eminent domain, based on the British colonial Land Acquisition Act of 1894, government can acquire land from farmers if it is for a project that is for the ‘good of the nation’, but it must offer a fair market price (see D'Rozario, n. d.). The Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board (KIADB), however, offers a relative pittance to the non-elite members of rural communities, exercising its right to choose the depressed rural market price and not the upscale world-city market price as its marker. The difference comprises ‘the rent’ that shapes and fuels the new urban economy and its governance structure: the black, grey and white markets of real estate brokering and speculation, the mega-deals conjured for new highway, special export zone (SEZ) and township construction, and the new governance system ‘managing’ these transitional steps toward becoming a world city.

(p. 566)

Speculating on land and dispossessing inhabitants therein are at the centre of the transformation of rural peripheral space into a furnace of real estate industries and industrial production. The experience of Mumbai is another testimony to how the secondary circuit of real estate has risen above the primary circuit to bring about the complete urbanization of Mumbai and its adjacent regions. The growing recognition of the role of real estate is also evident in the work of Datta (2015) on entrepreneurial city-building in India. She highlights the role of the Indian state in bringing about mega-urbanization in Indian cities (see Figure 2.3), which results in the creation of new avenues of capital accumulation. Obviously the avenue is filled with an Indian version of gentrification or neo-Haussmannization.

Suburban or ex-urban development that installs newly built forms on lands relatively free of legal and socio-political constraints is relatively speaking an attractive option for ruling elites in comparison with development in dense urban cores. Mohamed Elshahed (2015) for instance examines the urban development process in Cairo where suburban urbanization has been a dominant feature of urbanization. Desert land usually owned by the military has been given to private investors through direct sales, resulting in the development of private, gated suburban estates. Despite on-going interest from private investors in exploiting the potential of Cairo's historic downtown, full of heritage sites, gentrification has not taken off there for now, due to extant rent controls as well as legal fights involving owners and inheritors. As Elshahed (2015) summarizes:

downtown's gentrification potential is limited due to its location in a city where real estate investment is directed towards the desert periphery, where suburban developments are mushrooming…Potential gentrifiers, young couples, are often unable to borrow from banks (red lining) to buy and restore apartments in the decaying urban core, such as downtown. However, borrowing for the purchase of real estate in new desert communities is facilitated.

(p. 125)

However, this does not mean that the historic downtown is to stay as is. In an increasingly booming real estate market, underdevelopment leads to greater development potential. Elshahed (2015) himself hints at latent gentrification in other parts of the urban core outside of the historic downtown area. This is especially with regard to ‘the emergence of a rent gap in the inner city resulting from skyrocketing land values with properties of limited investment return’ (p. 125), and how the rent gap formation often leads to the acquisition of run-down heritage buildings in pockets of Cairo's urban core (especially neighbourhoods in working-class districts adjacent to the downtown area as well as in the historic core), which are then demolished to give way to tall residential condominiums, a process that is often illegal. This process is further facilitated by the state's effort to exercise the forced eviction of thousands of families, particularly in relation to the creation of a new central business district in the Maspero Triangle north of downtown Cairo (Elshahed 2015: 126).

It is useful to be reminded at this point that the intensification of peripheral urbanization or suburbanization is not to be taken as an alternative to investment in existing urban cores. In fact, the two processes complement each other as part of the profound dynamics of uneven development: ‘[t]he logic of uneven development is that the development of one area creates barriers to further development, thus leading to an underdevelopment that in turn creates opportunities for a new phase of development’ (Smith 1996: 84). Gentrification-induced displacement may also contribute to peripheral urbanization or suburbanization. For instance, as the Anti-Gentrification Handbook for Council Estates in London (London Tenants Federation et al. 2014) shows, peripheral London boroughs turned out to be the destinations of most people displaced from central London. A similar case is witnessed in Santiago de Chile, where low-income displacees from gentrifying central quarters of the city have been pushed to outer suburban areas due to their inability to afford replacement accommodation in their original neighbourhoods or adjacent areas, thus reinforcing the traditional suburbanization of poverty seen for decades in Latin America (López-Morales 2013a).1

In an uneven process of development and accumulation, existing urban cores are not to be the exclusive zones of incoming reinvestment, and ‘[t]he differentiation of the city from the suburbs…will be matched by the continued urbanization of the countryside’ (Smith 1996: 85). It is in this context of uneven development and the intensification of peripheral urbanization that we can also revisit existing studies on non-typical gentrification, such as the rural gentrification depicted in the literature on counter-urbanization (see Phillips, 2004). Having mostly grown out of the rural context of the UK, the counter-urbanization literature often examines the characteristics of rural in-migrants, which can be either differentiated from or run parallel to those of urban gentrifiers (see for example, studies by Phillips 1993 and 2002). But Grimsrud (2011) warns against the uncritical application of counter-urbanization that has emerged out of the experiences of core European or American regions, arguing that in Norway, the motivation to initiate urban-rural migration mostly rests on economic or family reasons rather than anti-urban life preferences. Nevertheless, the study of ‘wilderness gentrification’ by Eliza Darling (2005) in a US-based natural park also reminds us that it is the underlying logic of capital accumulation that gives rise to a localized form of disinvestment that differs from the way it is practised in urban areas but still produces a unique gentrification landscape for both local renters and holiday guests.

New urbanism, re-urbanization and gentrification

The previous section largely discussed the impact of emerging discourses of planetary urbanization and global suburbanism upon gentrification debates. We now move back to the post-industrial cities of the global North, which were known to have suffered from inner-city depopulation, the emergence of brownfield sites due to deindustrialization, and the financialization of the conventional urban core (especially in some of the leading cities in the global competition for investment). Here, the case of ‘new urbanism’, popularized in the 1990s and early 2000s in Western European and North American countries, is a useful entry point for its recent influence on real estate markets and gentrification debates. In the context of the detrimental impacts of suburban sprawl, deindustrialization, and to some extent urban shrinkage, ‘new urbanism’ emerged as a remedy to these negative consequences of contemporary urban development in the post-industrial era of capitalist development. New urbanism called for creating a new sense of community through the promotion of high density construction, new design of buildings and landscapes, and the application of sustainable development initiatives (Calthorpe 1993; see also Moore 2013 for a more critical discussion of New Urbanism and its status as best practice). Inner-city regeneration in the West has increasingly taken the form of new build, often densifying the existing built fabric through demolition and reconstruction of condominiums to maximize returns on investment by developers or individual speculators. Projects under the banner of ‘new urbanism’ aimed to combine inner-city living with the suburban aesthetic, often branding new residential developments as ‘urban villages’ or variants. New urbanism projects also frequently targeted derelict or abandoned old industrial sites, changing land uses to accommodate residential projects that usually accommodated young professionals in search of temporary nests before transitioning to a more formal solution. The question was (and still is for some) if this qualifies as gentrification.

In his discussion of the urban regeneration of former industrial land in London's Docklands, Butler (2007b) was more cautious about the use of the term ‘gentrification’ as a way of understanding the transformation the area had gone through, largely because of the particular aspirations held by the new occupants. Influenced by the rise of new urbanism under the then New Labour government, the London Dockland's regeneration, a project that had been protracted for decades, finally saw its implementation. While the project displayed evident signs of ‘regeneration by capital’, the new denizens appeared to possess an ethos similar to that of suburban dwellers, that is, ‘to be near but not in or of the city’, displaying ‘a very different profile in terms of gender and family structure – suburbia for singles and empty nesters, as it were’ (Butler 2007b: 777).

Butler's focus on the habitus of gentrifiers (new occupants or denizens as in the re-urbanization discourse) obviously had an effect on how gentrification was understood. In the socio-political framing of contemporary cities centred on urban decline and poverty, especially inner-city areas, public policies to bring about urban revitalization and urban renaissance are seen as positive measures that produce new-build residential developments, coined ‘re-urbanization’ by some, rather than ‘new-build gentrification’ – see for instance, Boddy's (2007) discussion of the inner-city redevelopment of Bristol, which involved the conversion of largely commercial properties into new-build residential properties to accommodate young professionals in transition, residing largely in buy-to-let properties. The absence of clear signs of direct displacement of existing resident populations by the new denizens nor overt political contention over the new developments led Boddy (2007) to reject use of the term ‘gentrification’ and to opt for the more politically neutral term ‘re-urbanization’ (see Davidson and Lees 2005 and Slater 2006 for a critique). This conclusion was despite the clear signs of speculation by absentee owners (in the form of buy-to-let investments in new developments) and developers, and the on-going classic gentrification in adjacent neighbourhoods, which may have been concluded by the class remaking of the inner-city areas.

A number of problematic positions can be identified in the above re-urbanization arguments. These include the labelling of buy-to-let buyers as investors despite clear signs of their speculative behaviour. Furthermore, a restricted understanding of displacement is apparent in the writings. The re-urbanization thesis refers to the absence of displacement as key evidence in its rejection of gentrification, but for Boddy, displacement is limited to the absence of direct last-resident displacement, which is only one of the four dimensions in Marcuse's (1985a) insightful conceptualization of displacement (the other three are chain displacement, exclusionary displacement and displacement pressure). There is lack of account for the displacement of existing retailers or work places as well as workers who used to have some degree of affiliation and sentiment to these places. The claim of re-urbanization based on a lack of physical displacement of a working-class population is repudiated by Davidson and Lees (2010: 408) who argue that new-build residential redevelopment accompanies ‘the alteration of the class-based nature of the wider neighbourhoods’. In particular, they call for a more nuanced understanding of displacement ‘as a complex set of (placed-based) processes that are spatially and temporally variable’ (Davidson and Lees 2010: 400) rather than reducing it ‘to the brief moment in time where a particular resident is forced/coerced out of their home/neighbourhood’ (ibid.). Invoking both Marcuse's typology of displacement and also Yi Fu Tuan's distinction between space and place, Davidson and Lees (2010) argue that ‘displacement is much more than the moment of spatial dislocation’ (p. 402; original emphasis), and that ‘A phenomenological reading of displacement is a powerful critique of the positivistic tendencies in theses on replacement; it means analysing not the spatial fact or moment of displacement, rather the “structures of feeling” and “loss of sense of place” associated with displacement’ (p. 403; original emphasis). In this respect, the class remake of urban space through capital reinvestment such as those seen in inner-city regeneration led by the (new urbanist) rhetoric of social mix or urban renaissance (see Bridge, Butler and Lees 2011) actually contributes to the displacement of working-class and poor residents and increases their alienation from the very place they have long been attached to. We expect to see greater attention to the phenomenological aspects of displacement in future studies on gentrification, and on the sentiments of inhabitants (users and owners alike) due to the loss of home and work places in gentrification processes.

Conclusions

Earlier in this chapter, we discussed how gentrification debates have long been preoccupied with a geographical focus on inner-city areas, even if there were attempts to reach out to the suburban and rural instances of mutating gentrifications (see Lees, Slater and Wyly 2008: 135–8 and Charles 2011). To some extent, the earlier focus on inner-city areas or singular centrality reflects the legacy of the modernist thinking of how cities have evolved over time. More recent innovative and path-breaking thinking of the urban and urbanization at multiple scales has steered our attention to a rethinking of centre-periphery relationships and also the diverse nature of urban development that results in multiple centralities. In short, we believe that a certain specific geographical locus (the inner city) should not be taken as a necessary condition for gentrification. Neither should gentrification be taken as a certain predefined condition (old architecture) and scale (e.g. local, neighbourhood).

Cities aspire to become world cities, and this aspiration is contagious, inflecting other regional cities within a country to emulate the ‘worlding’ of more influential cities (Roy and Ong 2011). One of the major outcomes of this is the heavy speculation on real estate, resulting in the rise of speculative urbanism (Goldman 2011; Shin 2014a). As land values rise, capital finds real estate more seductive and stays there. Not all displacement is gentrification induced (see Chapter 7 on development-induced displacement for example). But it is important to acknowledge the positioning of gentrification as a process in condensed urbanization. For Merrifield (2013b), however, it is neo-Haussmannization that sweeps the urbanizing landscape, turning each land parcel and landed property into virtual commodities floating in the air, to be snatched by speculators:

the world now is a project of neo-Haussmannization. In Haussmann's Paris we saw the centre being taken over by the bourgeois and the poor people being dispatched to the periphery, to the banlieue, and the centre was commandeered by the rich, and the poor were then displaced to the periphery, particularly to the northeast of Paris. Now, what I want people to do now is to imagine this not occurring in one city, but to see the whole urban fabric as being put in place through a process of neo-Haussmannization, whereby centres and peripheries are everywhere.

(p. 13)

The onset of neo-Haussmannization is perhaps the beginning of a planetary gentrification that no longer makes a distinction between central and peripheral locations, between neighbourhood-scale and metropolitan-scale real estate projects, between incremental upgrading and wholesale redevelopment, between physical displacement and phenomenological displacement, and between residential and commercial make-over. The underlying commonality is the logic of capital accumulation, especially the ascendancy of the secondary circuit of real estate, which enables multiple forms of gentrification, thus gentrifications in a plural sense, taking place around the world in a variegated way. The place specificities of this process are important, as many critics highlight in terms of emphasizing the contextual understanding of concept and phenomenon (Lees, 2000), but an equally important emphasis is on the ‘order and simplicity of gentrification’, which allows us to move from localized neighbourhood transformation to the greater picture of actually existing capitalist accumulation that brings together not only (domestic and transnational) gentrifiers but also urban social movements that challenge the existing social, economic and political order.

But when gentrification expands at the planetary scale, what is it going to become? Is it going to experience a qualitative transformation, becoming something else? Ruth Glass did not have the chance to observe global gentrifications – neighbourhoods were the units of gentrification in the 1960s and 1970s, although she was very much aware of the importance of scalar thinking (see Chapter 1) in that neighbourhood transformation was not understood as isolated from wider metropolitan changes. Many research projects on gentrification have been bounded by the traditional notion of the city, inward looking, without making connections with the rest of the city, region and the world. Emphasizing the importance of understanding how urbanization unfolds in peripheral suburban regions, Keil (2013: 10) states:

There is much blurring and bleeding among and between the different world regions. In a post-colonial, post-suburban world, the forms, functions, relations, etc. of one suburban tradition get easily merged, refracted, and fully displaced in and by others elsewhere, near or far. Our optics has changed accordingly and we have collectively been challenged to abandon historically privileged sites for observing urbanization.

Gentrification research has also gone through various challenges over the years in abandoning its classical assumptions, such as a focus on inner-city areas, residential landscapes and rehabilitation. But it may be necessary now to push further this theoretical re-orientation in order to steer research efforts towards integration with new understandings of the urbanization processes that are unfolding, as we speak, at the planetary scale.