Leaving Chicago, I decided to drop in for a visit with a relatively new worker-owned manufacturing cooperative. My phone GPS guided me as I dodged trucks and potholes through the Brighton Park warehouse district. A hand-lettered sign above the loading dock said, “New Era Windows Cooperative.” I asked at the office, and Armando Robles, one of the worker-owners, took time away from his work to talk.

Before it was a cooperative, the workers at what was then Republic Windows and Doors were simply told what to do, Robles told me. He had been a maintenance worker at Republic and president of United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers Local 1110. The workers there might have seen ways to improve the production process, but their supervisors weren’t interested, he said.

“Whatever the bosses want, we do it. We’d say, ‘Look, this is a better way,’ and they’d say, ‘No, we say you have to do it this way,’ ” explained Robles. “Even when they made a mistake, they just continued.”

The situation is very different today. Employees of the New Era Windows Cooperative are also the owners. And their ideas matter. Anyone can propose improvements, and if that person convinces a majority of coworkers, things can change quickly.

“If we make a mistake, we talk to each other, and we find a solution,” said Robles. “We try to do the best for everyone. We work harder because we’re working for ourselves. But it’s more enjoyable. We work with passion.”

Each employee-owner has the opportunity to develop a wide range of capacities, instead of being confined to repetitive work while those at the top of the hierarchy make all the decisions and most of the money. Because workers are respected and heard, they tap into a resource previous owners had neglected—the smarts and creativity of the entire workforce.

Armando Robles and Beatriz Gurrola, worker-owners of New Era Windows Cooperative.

Becoming a worker cooperative was a long journey, and it was a journey no one had planned. It began in the winter of 2008 when Republic’s owners closed the factory and laid off the workforce without the required 60-days’ notice. Workers occupied the factory and refused to leave the premises until they were paid what they were owed in severance pay and wages. Robles was one of the leaders of the occupation.

The story went nationwide. Pressure from the union, area activists, and even President Obama led to a victory: the workers were paid, and instead of shutting down, the factory was sold to California-based Serious Materials.

The workers kept their jobs, but the experience radicalized them. Several visited Argentina with Brendan Martin of The Working World, which, for some years, had been helping to finance worker-owned factories in that country. Robles and others from the Chicago company learned that workers facing the same situation had occupied their factories and eventually become worker-owners.

So Robles and his coworkers were prepared when, three years later, Serious Materials announced they would shut down and liquidate the factory. Once again, the workers occupied. With a nationwide petition drive, support from United Electrical Workers, financing from The Working World, backing from the local Occupy movement, and the memory of the previous occupation still fresh in the minds of the Chicago power elite, the protest turned into a buyout.

The New Era Windows Cooperative has been in operation since 2013, and the employees now run the business. It’s been a steep learning curve. “It was difficult to make decisions together,” Robles said. “But it’s kind of fun, because at the end of the day it’s for the benefit of everyone.”

Sales are modest, but growing. There are 23 worker-owners, and two staff members who Robles hopes will opt to become worker-owners.

How is this company staying alive when other owners have failed? The worker-owners made tough decisions to cut costs. They streamlined the products they offer, moved to a more affordable facility, and got rid of equipment that required costly upkeep. They did a lot of sales via word of mouth—the company prides itself on producing energy-efficient windows and doors customized to client specifications.

These worker-owners understood the challenge of competing with larger businesses that often get government subsidies and tax breaks or that operate in low-wage countries. Still, they have some advantages. Items that are heavy and expensive to transport, such as windows (and food), give local production an edge. Plus, “the good thing is we don’t have the CEO making millions of dollars,” Robles said, “so we can compete.”

Instead of wealth being extracted from the work of New Era employees, profits circulate back into the enterprise and into the workers’ equity. The cooperative may not make the big profits of companies producing in low-wage regions, but it offers other sorts of returns, such as steady employment and work that provides dignity and opportunities to grow professionally. New Era also offers the security that comes from being part of a community that cares about many values—including the common good. That community came out to help the workers when they were occupying the factory and later during the buyout. And they give back by making environmentally sound products.

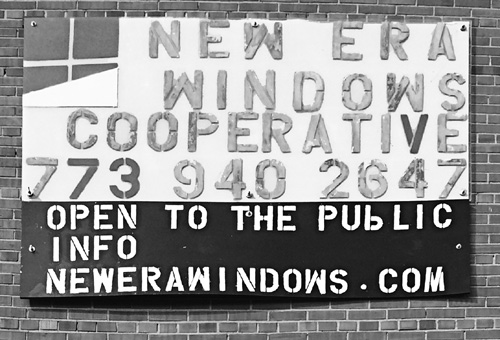

Sign at entrance to New Era Windows, Chicago.

New Era’s worker-ownership model offers something else: it’s based on “enough.” Enough pay and benefits to live with dignity. Enough production machinery, but not the sort that is too expensive. Enough profits to reinvest in the company, but worker-owners are free of the burden of producing high and growing profits to satisfy absentee shareholders. The Working World’s “patient” financing put the priority on the success of the cooperative, not on large or rapid returns. This sense of “enough” counters the impulse to extract and degrade. Instead, this cooperative has created a model for abundance and shared prosperity.

A statement on their website suggests they know that their workplace is revolutionary: “Like all U.S. pioneers, the paths we blaze are open for other adventuring souls to follow, and we look forward to being part of the next renaissance of ‘made in America.’ ”