La Pitchoune

THE SEA DANCED in the rearview mirror and palm trees waved a welcome as the rented Peugeot headed inland. It lurched through hairpin turns, swooped down a final hill, then up a dusty drive toward a construction site. Julia let out a whoop when she saw the half-finished stucco house perched on the hill. La Pitchoune, “the little thing,” was the dream that got them through some dark days and cold nights in Plittersdorf, near Bonn, and Oslo. Since leaving France in 1954, they had fantasized about a place of their own in la belle France, maybe a Paris pied-à-terre on the île Saint-Louis or in Montmartre. But in the end they were lured by the azure skies and perfumed air of Provence, and an offer too good to pass up.

Several months earlier, on Simca’s patio in southern France, warmed by the sun and not a little wine, Julia and Paul decided this was their paradise, so they meandered through nearby country towns looking for something for sale. Valbonne. Opio. Mougins. Every charming old stone house they looked at turned out to be more picturesque than livable. But Simca’s husband, Jean, had a proposal. Why not build a house here at Bramafam, his family’s property? They could design it to suit themselves. The land would be leased, and return to his family when they tired of it.

Little chance of that. Julia had fallen for the South of France on her first trip there, in the winter of 1949. Bright blue skies, views of distant mountains, and year-round fields of lavender and roses took her back to childhood summers on the California coast. Paul, with his painter’s eye, was equally enthralled. They sealed the deal with a handshake on the spot.

The house would be almost paid for by sales of Mastering, already in its sixth printing. And it wasn’t hard to rationalize the expense of a second home, since they were already planning a second cookbook. It would be much easier to walk the few yards to the side door of Simca’s kitchen than to send reams of recipes back and forth across the Atlantic, as they had for so many years.

They were only too happy to leave the oversight of the crusty local builders to Jean, and on this first inspection trip, everything was just as they had imagined: a room for Paul to paint and putter, a private nook in Julia’s bedroom for her books and typewriter, and a compact kitchen, all on one floor. They’d even have room for a guest or two, and more if Paul bunked in a little cabanon, a onetime shepherd’s hut a few yards from the house.

For months after they returned to Cambridge, Julia kept a letter from Simca tacked to her office wall. It was filled with local gossip, the adventures of her dog, Phano, and relief that the carpenters and plumbers had packed up their tools and were finally gone, along with the dust and noise. Only one more thing would make the dream house complete. Simca closed with the best news of all: “Madame Pussy cat had two kittens with her little mate, so you’ll have a pussy-cat for your arrival in December and to chase the mice at La Pitchoune.” At last, purrfection.

JULIA’S FACE FLOODED with happiness every time she thought about going “home” to France once again. “La Peetch” would be the respite she and Paul craved from the whirlwind of activity that had begun with a book review program on what Paul described as “an egghead public television station” in Boston. She had cooked an omelette on a hot plate but got so carried away with the demonstration, she forgot to plug her own book. One bowled-over viewer wrote to food critic Craig Claiborne and demanded that he review a book by a big, strange woman she saw on TV. Shortly after, Claiborne’s rave review of Mastering the Art of French Cooking appeared in the New York Times. Soon, The Book was flying off shelves and Julia had a television program of her own.

By 1965, “the French Chef” was finishing her third season, well on her way to becoming a TV star, and while she was eager to share her enthusiasm for the pleasures of the table, the nonstop activity—shopping, scriptwriting, rehearsing, schlepping gear from home, and promotional events—took a toll. The public couldn’t get enough, leaving her and Paul with little time for themselves. And no time or place in her hectic life for a house cat, so she was counting the days until they left for their getaway in Provence, where a kitten was waiting.

Since they would be gone for months, Paul was trying to shoehorn an entire household into their battered trunks—aspirin, toothpaste, toilet paper (the soft American kind), and way too many clothes, including heavy New England overcoats, just in case. Plus his painting supplies, the skillets and gadgets she couldn’t live without, and pegboard hooks to hang them on, just like the ones in the Cambridge kitchen. Fortunately, he told his brother, one crucial item had been taken care of: “Arrangements for a pussy-cat have been laid on.”

When they arrived in Cannes, several of the trunks were missing, especially worrisome since they held Julia’s precious recipe notes for the sequel she had nicknamed “Son of Mastering.” But nothing could dim the excitement as they drove up to their own little piece of Provence for the first time as homeowners. There, just fifty yards from Simca’s old stone farmhouse, stood la Peetch with the afternoon sun glinting off the tile roof and freshly painted green shutters. Paul thought the house looked “smiling & scrubbed behind the ears, as glad to see us as we were to see it.”

They were greeted by the usual tsunami of barking, tail wagging, and miaouing, and the yelps of an exuberant new puppy. As bonjours and air kisses flew, Julia looked around hopefully for the special poussiequette Simca had promised. Finally, she spotted a pair of bright eyes calmly studying the newcomers from the safety of the stone steps, as if waiting for a formal introduction.

Julia knew the white, black, and brown kitty was The One when he jumped down, rubbed against her ankles, and made a quizzical trilling sound. This people-loving kitten had already acquired a reputation as a Prince Charming who could coax treats from anyone and who ruled the whole menagerie with, as Paul proudly noted, “the loudest purr in Christendom.” Julia happily surrendered to his charms and decided to name him “le Petit Prince.” He was the first in a line of la Peetch cats over the years to answer to that noble name.

Julia and Paul were bone-tired from the long travel day, but relieved when they got word that their precious trunks had been found at the station. They would collect them in a few days when Julia made the first of her weekly trips to Elizabeth Arden for her mise en plis, her curly do.

That evening, Simca invited them for a sumptuous meal marked by several rounds of welcoming toasts. In a pleasant after-dinner buzz, Julia and Paul ended their first la Peetch day on their own terrace, drinking in the sweet night air. The lights of the tiny village of Plascassier shone across the valley and stars glimmered in the cobalt sky. Their new amour, le Petit Prince, padded out from the shadows of the mulberry tree, leaped nimbly onto Julia’s lap, and purred so loudly Paul feared he might wake the neighbors.

Once again, Julia rested in the embrace of her three loves—an adoring spouse, la belle France, and a poussiequette of her own.

Bienvenue!

CHRISTMAS WAS JUST around the corner and the three “mad women of La Peetch”—Julia, Simca, and Avis DeVoto, their friend and agent who’d come from Boston for the holidays—were as excited as les enfants waiting for le Père Noël. It was also foie gras season, and the trio of cooks couldn’t wait to get their hands on the quivery pink livers. In a raucous mix of English and French they argued about which delectable dishes to cook up for their holiday feast. Would they grind it with truffles for spreading on croutons? Would they blend it with prunes to stuff the traditional holiday goose? Would there be any left when they were done tasting?

To a stranger it sounded chaotic, everyone talking at once above the sounds of slicing, dicing, pounding, and sautéing. But to Paul’s practiced ear, and from the safe distance of his den, it was “a jolly, pleasant symphony accompanied by the smell of hot olive oil and a sense of gustatory goodies to come.”

The feline residents saw no point in waiting. They wanted their goodies, and they wanted them meow! Banished from the kitchen and wild with the scent of goose liver, the cats hurled themselves at the door, sticking like magnets to the screen. Unmoved, the three cooks just raised their voices a notch to drown out the din. A pampered Petit Prince was especially incensed at being exiled from his domain, but for once Julia ignored her favorite’s pleas. She was methodically making notes in her looping script about each step in the cooking process. She didn’t want to miss a chance to learn something from this boisterous foray into foie gras.

Julia and Simca carried on about the best way to temper the assertive taste of goose liver: Add cognac, port, or Madeira? Which spices? How much pork fat? Such spirited debate was nothing new. The strong-willed partners kept up a friendly battle over how to cook every dish. Simca insisted that every recipe be authentically French, but Julia cared more that American cooks be able to easily duplicate it with supermarket ingredients. With a best-selling book and a wildly popular cooking show, Julia was now more confident challenging Simca. They argued as if lives were at stake, but in the end they always worked out a compromise, because they kept their eyes on the prize: How does it taste?

The bond between them was wide and deep. They shared a passion for France, for fabulous food and teaching others how to make it—and for cats. They even shared joint custody of a favorite kitty. When the big black-and-white cat stayed with Simca, she answered to the name Whiskey, and at la Peetch, Julia called her Minoir. They were both taken with her dainty habits. She liked to watch TV, strike dramatic poses, and drink water from a glass at the dinner table.

As the dinner hour approached on Christmas Eve, the whole house smelled of goose cracklings, and Paul followed his nose to the kitchen, where the three triumphant cooks stood back admiring their elegant pâtés. Paul popped open a Dom Pérignon to salute their team effort. The not-so-happy cats, still pouting and pacing outside the door, had failed to melt any hearts.

It was a grand Christmas dinner, everyone agreed, including the cats, who, in the spirit of the season, forgave all after they feasted on the remains of the gloriously golden goose. But some cats were more equal than others. Only le Petit Prince tasted the divine pâté.

Whiskey/Minoir

JUPAUL TOOK CHARGE of the animal kingdom when Simca was away teaching in Paris, and it kept them hopping: “What with cats and dogs and feeding them, we are a veritable veterinary establishment right here!” With so many needy critters around, work on the final editing of Julia’s French Chef Cookbook slowed to a crawl. The cats were happy, but her New York publisher not so much. Julia shrugged: “Voilà—la vie!”

One day she dashed off a distressed note to Simca. One of her favorites, the big gray Minou, looked très malade. “Yesterday he was the most miserable eye-streaming old pussy imaginable—when they say ‘sick as a cat’ he was it.”

She and Paul dropped everything, bundled the poor thing in an old blanket, and nestled him on the backseat of the Peugeot. He was too sick to put up much of a fight. They shooed his miaouing posse out of the way and took off for the nearest vet, in Grasse, where they were alarmed to hear that a dangerous virus was making the rounds of neighboring farms.

Julia could hardly bear to look into Minou’s soulful eyes when they had to leave him overnight, but she was anxious to get home, suddenly fearful for her Little Prince. She watched over him all night as he became listless and wracked by fits of sneezing. In the morning, another frantic ride to Grasse with an unwilling passenger curled in her lap. She stroked his head and urged Paul to please take the twisty country roads just a little faster.

After the Little Prince got a shot of antibiotics, she insisted on taking him home to his castle, where she could administer megadoses of motherly love. For days she and Paul nervously followed the other kitties around the yard listening for any tiny achoo! The pussycat plague eventually ran its course, but not before she had to give Simca the sad news that her handsome gray cat did not survive. The medicine came too late, and when he refused even the chicken liver pâté she brought from home, they had to face the awful truth that this Minou had run out of lives. They were devastated: “A very sad business, and we both cried, in fact I am still crying.”

Their only solace was a more hopeful prognosis for their own poussiequette, although it was still touch and go. “The darling Petit Prince has had his third injection and will take some medicine for four days.… We pray he will be all right, and shall watch him carefully.” Their prayers were answered. The vet marveled at the miraculous recovery and gave full credit to Julia’s potent brand of TLC.

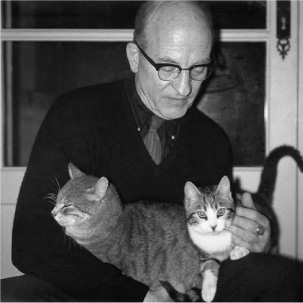

LE PETIT PRINCE, the kitty with the powerful purr, was the first in a cavalcade of cats Julia pampered at la Pitchoune. Only Paul knew how deep Julia’s attachment was to each of them. He confided to his twin, “A cat—any cat—is necessary to Julia’s inner satisfaction.”

When they returned to Cambridge each year, their sadness at leaving a special cat eased only when Simca wrote that their kitty had been coaxed into rejoining the miaouing chorus at her kitchen door. “Your poussiequette stayed in front of la Pitchoune for 48 hours, always hoping to see the door open, but he didn’t want to come, despite our appeals. We had to take him in our arms and carry him into the house so that he’d finally agree to eat. Alors, then he did justice to his dinner, and now rests for the night in the kitchen waiting for breakfast.”

Letters between the two partners crossed the Atlantic almost daily, packed with recipes and notes that kept their cookery bookery enterprise humming. Julia’s jammed typewritten pages and Simca’s scrawls in a mélange of French and English captured the daily rhythms of their lives, spiced with local gossip and the doings of their favorite cats. No surprise, the subject was often the capricious feline palate.

Julia: “How is my pussycat (I think of her every time I throw out a boiled chicken neck!)”

Simca: “La Minimouche behaves herself very well, demands her share at dinnertime and waits until she has been fully served.… She looks splendid—let’s hope she doesn’t become enormous.”

Julia: “How is our Minimouche? Is she getting very big? I hope so, as I adore great big poussiequettes.”

Handle with care

Simca ruefully replied that Julia’s kitty was too much the gourmand and sometimes resorted to thievery despite her generous portions. One day, in the blink of an eye, she gobbled half a pastry tart that was waiting to be garnished. Julia was amused by the antics of her little thief: “Our Poussiequette sounds magnifique.”

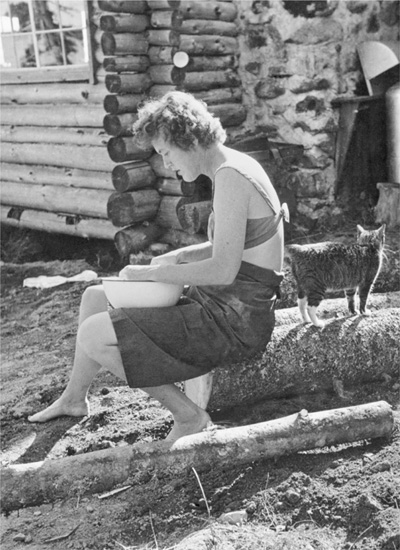

While on vacation at the log cabin Paul and Charlie built in Maine, Julia wrote letters to Simca that filled her in on the status of her extended family of cats: “PS: The two pussies here, Pewter and Copper, are beginning to show their age a bit, both are 14, and though still catching mice, are beginning to look big and ruffled and a bit elderly.”

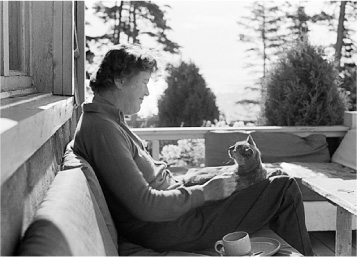

Julia with her sous chef in Maine

She enjoyed her foster kitties but pined for news of her true loves at la Peetch. She implored Simca for reassurance that out of sight did not mean out of mind. Or heart.

Julia: “We do hope Minimouche will remember us some months from now?? Perhaps we should rush over for 2 days to refresh her memory.”

Simca: “Your pussycat hasn’t forgotten you because this grand cat is constantly parked between la Pitchoune and le Mas, in expectation of your arrival.”

Julia: “How good it will be to see our dear ones.… Tell Poussiquette to get herself ready for us.”

As the time for the reunion approached, Julia couldn’t contain her excitement: “Please tell Minimouche that we are almost on our way.”

In her last letter to Simca before departing Boston, Julia looked forward to a kitty welcoming party: “Shall you be bringing your little poussiequette? We hope so. I shall stop at Le Casino in Cannes and get some raw liver pour enjôler [to entice] Mlle Minimouche who will have forgotten us. “

No chance of that. At the sound of that familiar high-pitched trill, Julia’s poussiequette bounded out of the bushes and raced up the path to her customary post in front of la Pitchoune. While the liver was lovely, there was really no need for gifts. Julia’s kitchen door was open again at long last.

WHILE MOST COUNTRY cats never know where their next meal is coming from, the Bramafam kitties had it made, wearing a path between the kitchens of two world-class cooks who were both gaga over felines. One scrawny cat called Minimere was a mother lode of kittens over the years. Julia had a soft spot for the “Little Mama” because she knew that as long as the fertile feline stayed around, she’d never run out of poussiequettes.

Back in Cambridge Julia looked forward to the frequent birth announcements from Simca: “La Minimere has brought 3 kittens since this morning: a light gray one, like herself; a white and gray one; and an all-black one.” A happy Julia wrote back at once asking which one would be her special poussiequette: “We need a tough cat (un dur) who adores people, who is a gourmand, who is jolly and playful and who likes to walk with us, and wants to be with us every minute.” As the matriarch of the Bramafam kitty clan, Simca took her matchmaking seriously and always found the perfect fit.

One summer when Julia and Paul arrived at la Peetch for a short stopover, Minimere was predictably pregnant. Since the cat was eating for two or three or more, Julia filled her bowl to overflowing and rubbed her back until she was drowsy. Soon there would be new kittens to love. But because they were leaving soon to vacation with friends in Norway, they worried that the Little Mama might choose their house for her lying-in hospital.

JuPaul were no match for the wily mother-to-be. On the prowl for a secluded spot to deliver her brood, Minimere lurked near the kitchen door for a chance to sneak inside and settle in a half-open bureau drawer, a cupboard left ajar, or a soft basket of laundry. When Simca knocked, carrying a warm tarte aux poires, the cat slipped in and disappeared down the hall.

The next evening, amid a soothing soundtrack of twilight warblers, Julia sat correcting recipes while Paul jotted notes to Charlie. Suddenly an avalanche of tumbling bottles, splintering glass, and an ear-piercing “Yowwwwl!” jolted them to their feet. As they raced toward the din, a wild-eyed Minimere darted by as fast as her drooping tummy would allow.

The clever kitty had found an open closet, clawed her way up the coats, and built a cozy nest for her confinement on top of some bottles Paul had stashed on the shelf. Paul and Julia groaned at the mess but had to admire Minimere’s persistence and agility, and though it took the rest of the evening to clean up the sticky shards of Cinzano bottles, they counted their blessings. At least it wasn’t one of Julia’s precious Château d’Yquems. Never ones to cry over spilled wine or pass up a chance to celebrate, they opened the last unbroken bottle and toasted the mother-to-be.

When the spooked cat failed to appear for breakfast the next morning, Paul assumed she was “spawning future bottle-breakers in the hollow of some olive tree.” They knew the proud mama would soon come around toting her kittens by the scruff of the neck. When she dropped the miaouing balls of fluff at the kitchen door, Julia would be ready with some choice chicken parts and saucers of cream. Like any doting grandma, she couldn’t wait.

Eyes on the prize

THE MINUTE ANOTHER season of The French Chef was in the can, Julia and Paul started packing for Provence, where the pace of life slowed. Once settled in their snug retreat, Julia jotted to Freddie, “Left Paris absolutely bone-chill-frigid at 3 PM, came down out of clear blue sky w/ sun! Glad to be home w/ our own Pussy, our China tea, our houselet, our quiet, our sun, our flowers.…” And she added a bright red marginal note: “Our new pussy is a dear—tiger back and white feet & face & little tiger mustache.”

They named her Minimouche, and like all kittens, she was in perpetual motion. As soon as Paul opened the shutters in the morning, she shot outside like an arrow toward a bull’s-eye—a ring of yellow pansies around the olive tree—while Julia sang out, “Alors, Minimouche, fais oui-oui!” The kitten helpfully “watered” the flowers, then raced back for breakfast. On warm days they ate in the shade of the mulberry tree and lingered over the Nice-Matin newspaper, while the kitty chased lizards in the sun.

When Paul retired to his studio, Julia went to her alcove to tap out recipes. On a quest for the holy grail of baking, the secret to making real French bread in American ovens, she churned out golden crusty loaves almost every day. Even as he fought an expanding waistline, Paul was only too happy to assess the merits of each buttery loaf: “I shall eat it, my pleasure all the greater because of the partner facing me across the table.”

At lunchtime, he headed toward the slap-slap of Julia pummeling her yeasty dough. The insistent miaous of a hungry cat nipping at her ankles set off a round of futile but fond chiding: “Mimi! Ferme ta petite bouche! C’est défendu de faire ce bruit. Non, non, non!” (Mimi, shut your little mouth. I forbid you to make such noise. No, no, no!) Her falsetto scoldings made more racket than the cat’s begging, but she and Minimouche both seemed fond of their little game.

After a half tumbler of Côtes de Provence and a hunk of bread slathered with sweet butter, it was back to the studio, where Paul often painted until his fingertips grew numb. Meanwhile, Julia and Minimouche grabbed un petit somme (a little catnap) while waiting for the next batch of dough to rise.

In the late afternoon they took long walks with the kitty prancing along beside them. They loved to watch their high-leaping pussy pirouette after butterflies and surge up and down in the high grass with a rolling rhythm that reminded them of an antelope in the savanna. Paul, ever the worrier, fretted that their kitten might stray too far, but she always found her way back to them and flopped at their feet panting like a dog. The blissful days followed “like pearls on a priceless necklace,” he wrote. “We fairly roll in them, like pussies in catnip.”

Some winter evenings the fierce mistral winds set the trees dancing and rattled the shutters, making their petite maison seem more like Wuthering Heights. They lit the fireplace and tried to ignore the howling and creaking. While Julia mashed garlic for ragout Provençale, Paul read to her from a back issue of the New Yorker. If they could get a signal, they watched the news flickering on a small black-and-white TV.

Minimouche had little patience for fashionably late dinners and by eight was loudly complaining, which drew another affectionate scold: “Qu’est que c’est que cette bruit, petit monstre?” (What’s up with this noise, little monster?) But some juicy giblets always landed in her dish.

When the winds calmed and heavens cleared, they donned heavy sweaters to sip a nightcap on the patio under a moonless sky. In winter the Big Dipper hung low over la Peetch, stars flashed like a million fireflies, and an occasional satellite slowly arced toward the horizon while the tiny purring machine settled in Julia’s lap.

After they turned in for the night, the kitty sometimes disappeared into the blackness and they speculated about her mysterious nocturnal life. Did she hitch a ride on a broomstick with one of the local witches? The village gossips whispered about a certain farmer’s wife who was said to practice the black arts. Or was Minimouche headed for a secret tryst, a rendezvous with a petit ami? Time would tell.

THE STRING OF wonder days ended when Julia and Paul returned to Boston to finish A Dinner at the White House, a TV special that aired in March of 1968 and certified her status as a bona fide national treasure. They counted on a quick return to their charmed life in Provence and their Minimouche who, Simca confirmed, was “in a family way.”

Julia longed to play midwife, but a routine visit to her doctor brought shocking news. She had breast cancer and would need a radical mastectomy. Although she downplayed its seriousness, Paul, who fretted if his “wifelet” caught a cold or complained of a tummyache, was distraught. But Julia preferred to focus on returning to la Peetch and her poussiequette: “We were so looking forward to being there tomorrow afternoon, standing on that lovely terrace, smelling the lovely air, patting Pastis, stroking Mlle Minimouche.”

Typically stoic, Julia determined to put the surgery behind her: “No radiation, no chemotherapy, no caterwauling.” As soon as the doctor gave the okay, they flew to Provence for her long recuperation. Monitoring the pussycat pregnancy was just the distraction they needed. She wrote to Simca, who was teaching in Paris, “Mlle Minimouche de la Brague et de Bramafam-Pitchoune still has her kittens inside her. Jeanne said we shall have to wait for the turn of the moon! We have set out a nice box for her in la Poulailler.”

In a corner of the henhouse, they lined a cardboard box with shredded paper and cut a hole just big enough for Minimouche to fit through. When they thought the time was right—eyeing the cat’s tummy and not the moon—they nestled the mama-to-be inside the box. But the pampered kitty wasn’t accustomed to such rustic accommodations. Paul ruefully wrote Charlie that the kitty was back on their kitchen floor in half an hour.

Everyone in the compound went on kitten watch, but Jeanne, the Bramafam caretaker and font of country wisdom, preached patience and correctly predicted: “Now that the new moon has come the cat will have her kittens.” Like proud parents, Paul and Julia announced to family back home the arrival of five adorable kittens on the fourth of May.

The chatons were soon all spoken for and Minimouche seemed ready to resume her life—and midnight trysts. Paul thought it was time for permanent birth control, since one Minimere was enough to keep Bramafam in kittens. So off they went, “to Grasse at 8 AM with Julie, carrying our Mini-Mouche imprisoned in a cardboard carton. On its open top was tied a dish-drying rack so she couldn’t jump out.”

A place in the soleil

In the coming weeks Julia empathized with her fellow surgery patient. She still wore a rubber sleeve to prevent complications from her own operation, and dutifully performed painful exercises in order to regain full use of her shoulder and arm. Partly to placate a worried Paul, she took long daily naps and let Jeanne help her in the kitchen.

As always, the relaxed rhythms of life at la Peetch cast a restful spell. Summer’s full bounty was all around them in alfalfa fields, olive groves, and hillsides covered in every shade of pink. Farm women in big straw hats with white cloth bags around their necks harvested the roses that ended up in the perfume factories in Grasse. Day and night the air smelled of honey.

Gradually Julia found her way back to the kitchen, filling the house with her favorite fragrances: garlic, tomatoes, roasting chickens, and baking apples. The effect was magical for both patients. Paul gleefully reported that one morning, “as though Merlin had waved his wand over her, the little cat walked out of her sick-bay, ate a whole dishful of hamburger, drank half a puddleful of hose-water, rushed up an olive tree & was cured.”

In a parallel burst of energy, a reinvigorated Julia began to complain to Paul that she’d had enough of peace and quiet: “Breakfast at the same house, then work, then lunch, then work, then dinner, then work, then bed. Every day the same! No friends, no trips, no nothing!” Paul had to agree that it was time for the “French Cheffie” to return to Cambridge and get back into the thick of things.

WHEN JULIA AND Paul returned to Cambridge in the summer of 1968, they landed in the thick of things they hadn’t at all expected. Their house on Irving Street was within shouting distance of noisy political protests in Harvard Yard. They sympathized with the antiwar and civil rights demonstrations, but hated the climate of fear. When a brick flew through the window of a Harvard faculty neighbor, Paul decided to install an elaborate burglar alarm.

Feeling vaguely as if their home were under siege, Julia longed for the safety of la Peetch and the comforting companionship of her poussiequette: “We keep thinking we hear Mlle Minimouche calling to be let in—would that we did.” She missed having a pussycat underfoot at Irving Street, so when friends asked her to kitty-sit, she jumped at the chance.

Geoffrey arrived one evening in a large blue carrying case. After formal introductions, both Paul and Julia took an immediate shine to the big, orange, “somewhat neurotic” cat. Geoffrey needed pills twice a day, and given their advanced kitty nursing skills, they felt sure pill-pushing would be a snap. On the first try, Geoffrey opened wide, said “Meow!” and with perfect timing, Paul stuffed in a large capsule. Pas de problème! He smugly repeated the technique the next day, and the day after that. Later in the week, Julia’s slippered feet felt something squish. Looking behind the sofa, she found Geoffrey’s entire stash of soggy pills and came up with a more foolproof delivery system. She wrapped the pill in goose liver pâté and tossed it in the air. Geoffrey snapped it up before it hit the ground. Fait accompli.

Julia was used to hearing her voice compared to a foghorn, flute, sliding trombone, or worse, so she got a kick out of the odd sounds that came from Geoffrey’s voice box. She chortled to Simca that when he wanted to roam the neighborhood, “he comes up to say ‘Qweek, I want to go out.’ Then he disappears under the bushes and we find him later sitting by the front door, saying ‘Qweek, I want to come in.’ “

In no time at all, the visiting royalty ruled the Child household. He thrived on his vastly improved menus and grew more fond of his foster parents by the day. When Julia and Paul went out for an evening, Geoffrey faithfully waited for them on the pillar beside their front gate like a majestic stone lion. When Charlie and Freddie came for an overnight stay with their overly affectionate Briard, Geoffrey tolerated the slobbery canine but seemed glad to see them go so he could reclaim his privileged status.

A short time after bidding Geoffrey a sad adieu, Julia welcomed another houseguest: “A little white pussy cat has come to make her home with us for a few days; she had been abandoned, and was so loving and appealing we could not resist.” She bathed the bedraggled orphan, fattened her up with freshly ground hamburger, and lavished affection on her temporary lap cat until she found it a good home. Word of her hospitality soon hit the feline street, bringing a string of strays to her door. One liked to take his afternoon naps in a big olivewood salad bowl on Julia’s pantry shelf.

She embraced them all: “I do like a house with a pussy in it!” Every furry visitor proved her mantra, “Une maison sans chat, c’est la vie sans soleil.” (A house without a cat is life without sunshine.)

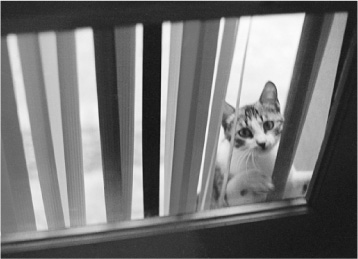

Let me in, s’il vous plaît

AFTER A FEW years of black-and-white reruns, The French Chef made a triumphant return in luscious color. Viewers thrilled to the eye-popping red berries and snowy crème pâtissière of Julia’s tarte aux fraises, the electric green of blanched haricots, and the rainbow hues of fresh mountain trout. A much larger budget let Julia and Paul take a production crew to France so viewers could see for themselves all the places she’d been breathlessly describing.

Off they went in the spring of 1970 to the dining room in Rouen where she had first tasted heavenly French food. They filmed Chef Dorin creating his famous pressed duck tableside, and then it was on to Paris to watch baker Raymond Calvel pull trays of baguettes from his brick oven. Julia led viewers through the aisles of Dehillerin, the “Old Curiosity Shop” of cookware, stuffed floor to ceiling with every gadget under the sun.

In Provence they explored the sprawling market on the edge of the Old City in Nice, a noisy bazaar of stalls heaped with the bounty of the countryside. Julia always stopped there on the way to la Peetch to buy armloads of tulips and tins of liver pâté to placate her kitty after a long absence. Close to home, they visited the ancient stone olive press at Opio to scoop giant ripe olives from a barrel of brine with a special olive-wood ladle.

Everywhere Julia went, she ran into “J-Ws,” a friendly but persistent gaggle of Julia-Watchers who greeted her like an old friend. Even in busy airports, parents thrust children upon her for a snapshot and regaled her with their own culinary adventures: “Finally I can make crepes!” And misadventures: “My soufflés just won’t pouf up like yours!” Maître d’s and waiters were excited to see her, and other diners always had to know what she was eating. Once in an airport restaurant, an Irish priest stopped by her table to express the gratitude so many seemed to feel: “God bless you, Miss Childs, ’tis a noble thing yer doin’.”

Julia was always gracious, though she and Paul sometimes ducked their heads when they heard loud American voices approaching. During the filming in Nice, a woman interrupted a crew lunch to exclaim, “My goodness! It’s Julier Chiles!… My daughter and I watch your program every Thursday night back home in Michigan. My friends just won’t believe it when I tell them I actually saw you in person!”

At times fan affection went too far. After the TV tour of Provence aired, the more intrepid J-Ws showed up in the untouristy village of Plascassier. Ignoring the gate, they trudged up the private road to snoop around the Bramafam compound, peering through the windows and French doors. The cognoscenti could tell which house was hers by the cats lounging on the patio or purring by the kitchen door. If Julia was home, she’d stop what she was doing to bellow a hearty Bonjooour! She’d sign the books they lugged and pose for “just one” picture, before politely excusing herself and sending the starstruck intruders on their way.

When fellow cat lovers discovered she was one of them, they showered her with cat trinkets, hotpads, aprons, nightshirts, and all kinds of cat-themed clothing, along with pictures of themselves with their own cats. One fan, who somehow learned that one of Julia’s Provence cats had died, offered to deliver a silver-haired pussycat “who looks like our dear departed” to the house on Irving Street.

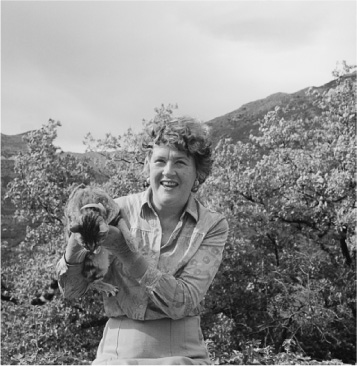

You wash, I’ll dry

Sometimes the mail brought strange requests. One writer hoped Julia would endorse her paper on “Cat Cookery,” filled with detailed recipes from cultures that viewed cats as suitable dining fare. Julia was repulsed by the whole idea, but still sent the woman a polite “I’ll get back to you.”

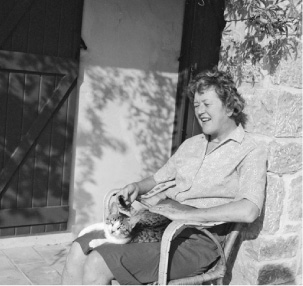

When Julia and her pussycat were shown cooking together in her own kitchen, it struck a chord. One cat-loving cook wrote, “Since I saw you in Bon Appétit photographed at your farmhouse in Provence with the cat in the kitchen sink, I have really felt you are my kind of people.”

Many fans found a special way to pay homage. For decades, countless well-fed cats from Boston to Bozeman answered to “Julia” when dinner was served.

BY THE SUMMER of 1977, Julia had taped more than two hundred French Chef episodes and finished an exhausting tour to promote From Julia Child’s Kitchen. She and Paul looked forward to the lazy routines at la Peetch—writing letters, pruning rosebushes, and eating lunch under their mulberry tree with a pussycat frolicking nearby.

Paul needed an extended sabbatical even more than Julia. Three years earlier, she’d convinced him to see about the chest pains he kept shrugging off, and he underwent triple bypass surgery. It probably saved his life, but their elation quickly faded. Julia confided to Simca that he had suffered small strokes during the operation and now often complained of being in a mental fog. She feared that her dynamic life partner would never be quite the same.

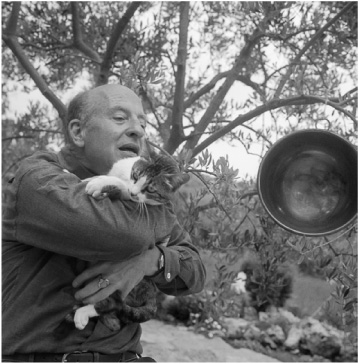

Mutual adoration society

More damaging than the crise cardiaque was the blow to Paul’s self-esteem. The eloquent writer who composed poetry in French and English was sometimes at a loss for words, especially when he tried to converse in French, leaving Julia to deal with shopkeepers and train conductors. He often felt frustrated and forlorn in crowds and was happiest filling his days with painting and photography, talents that didn’t forsake him. He put his faith in the invigorating air of Provence, which had helped restore Julia to full health after her own surgery.

Their peaceful days were enlivened by the adorable poussiequette Simca had waiting for them. He was a fine striped tiger, Julia bragged in a letter to her cat-loving friend M. F. K. Fisher. In homage to other favorites, they named him Minouche, a cross between “Minou” and “Minimouche,” but like all of Julia’s kitties, he was usually called by the affectionate Julia-ism “Poussiequette.”

Minouche was one of those cats who saw no compelling reason to make up his mind. This feline Hamlet wanted to be in and wanted to be out, as he pleased, and if the nimble puss found a window closed or a door latched, he made his displeasure emphatically clear. He was most vocal in the middle of an afternoon siesta or early-morning snooze. Julia had a habit from their Paris days of padding into Paul’s room, setting the alarm for eight, and curling up beside him for a few more z’s. The restless Minouche developed his own habit of pouncing at the precise moment they drifted off.

Sleepless, cranky, and exasperated by Minouche’s roaming ways, Paul engineered an ingenious solution. It took some patient explaining to the skeptical carpenter who came to install a special window over the kitchen sink that let Minouche come and go as he fancied. It was a win-win. Minouche could wander in and out to his heart’s content, while Julia and Paul could dally in dreamland a bit longer without visits from a perambulating pussycat.

JULIA WAS NOW a genuine superstar, the biggest public television had ever produced. A namesake Muppet lived on Sesame Street, and the real-life Julia cooked spaghetti with Mr. Rogers in his Neighborhood. Later he sent an exuberant mash note that captured her unique appeal for all ages: “Thank you for spaghetti and YOU!… You evoke a kind of loving admiration from those you meet.… You’re a grand person.”

The food world, tiny as it was then, recognized a good thing and welcomed her warmly. Until Julia came along, cooking on TV belonged to stern nutritionists or glamour girls like Betty Furness and Bess Myerson, whose culinary expertise began and ended with opening refrigerator doors. The exception was James Beard, who first appeared in the forties on tiny black-and-white screens that could barely contain his ample frame. He invited Julia to teach at his New York cooking school, and became one of her most ardent boosters and a dear friend who happily shared the kitchen limelight. The public found them both endearing—jovial, bighearted, and unpretentious. Julia and Jim made food fun.

JuPaul loved playing host to Jim and other foodies, friends, and family at la Peetch. They took everyone around to their favorite restaurants for a taste of authentic Provençal fare and to lively local festivals. Every spring the Fête de Roses in Grasse celebrated the rose harvest, the sweet-smelling mainstay of the local economy, where visitors sniffed and swooned over three thousand varieties of blooms. One year the organizers decided to combine the flower show with another wildly popular event, the annual cat show. Well. Julia and Paul thought that was a brilliant idea. Since their first pilgrimage to the Cat Club de Paris expo, they rarely passed one up.

At the “Cat and Roses Show,” they hurried past the flowers to get to the real attraction: “The roses were superb, but we were so drawn to those mysterious and fascinating creatures, the cats, that we did only a token walk-past of the roses.”

They strolled up and down the aisles, stopping at each cage so Julia could fuss over the competing kitties. In this temple of cat worship, Julia was like every other acolyte, blending into the crowd, until an American couple recognized the tall woman with the famous falsetto. It was hard to tell who was more agog—the Williamses when they spotted her, or Julia when they introduced her to their magnificent Persian puss. The couple had come a long way to enter him in the show, but now it didn’t matter if they won a blue ribbon or not. Running into the Julia Child was the prize they’d never forget.

Responding to Julia’s breathy oohs and aahs, the bedazzled owners pulled the fluffy cat with the outsize name “Lewishof’s Michael” out of his cage so Julia could stroke and hug him. Paul immediately sensed this was a mistake: “I thought for a few minutes I was going to have to use my bullwhip to force her to give it back to Williams, but by an act of immeasurable will-power and renunciation, she returned it.”

A few days later they were delighted to read in the local paper that Julia’s main squeeze took one of two top prizes at the show. Julia ripped the picture from the paper and tucked it into a letter home, so their Minouche would never find out about her cat-show dalliance with the dashing Persian.

AFTER A FIVE-YEAR absence from TV, in 1977 Julia agreed to a new series, Julia Child & Company. She’d put on some pounds and vowed to lose them before the camera added even more. Paul was watching the scale too, and lamented that he had to cut back on wine and settle for Château de Pompe, as the French call plain tap water, even when they dined at their friend Roger Vergé’s three-star restaurant. As for Minouche, JuPaul’s attempted loss was his gain, and he grew plump on the leftovers and nibbles the three would normally share.

Paul’s letters home focused on bigger losses—not just the pounds, but his physical limitations and changes to their peaceful corner of Provence. Paradise was being spoiled by Hollywood-style mansions. The influx of people meant more roads and the blight of transmission lines crisscrossing the hills. On a trip to Nice they were almost run down by American-style rolling carts in a huge new supermarket.

Julia was always more open to the new, especially when it came to gadgets that took the drudgery out of cooking, like the food processor. In a few spins, it could turn out quenelles de brochet, those scrumptious poufs that once had her pounding fish until she thought her arms would drop off. But she grumped along with Paul that the French seemed to be turning into convenience cooks. The supermarket was just the latest sign of a creeping Americanization of food.

One of the new things Paul did embrace was a Polaroid camera, despite his purist’s disdain for the “point the box and push the button” school of photography. Julia enjoyed the instant gratification of the new camera and got a kick out of taking snapshots of friends, furry and otherwise, who grinned as she sang out, “Smile, and say ‘Soufflé’!”

Julia loved to go along on Paul’s photo expeditions through the steep limestone hills and sleepy villages. He bragged that she was getting better at picture-taking herself, and it was probably Julia’s idea to rope Minouche into an experiment. Why not try to capture the cat as he leaped through his special kitty window? But she grossly underestimated the degree of difficulty. First, catch a wary cat. Second, try to hold on to the squirming, scratching, miaouing thing while Paul gets into position and checks his light meter. Third, persuade him to vault through the window on cue. Fourth, spend a half hour calling “Here MinoucheMinoucheMinouche” every time he manages to wriggle free and take off after a lizard or bunny or anything else that moves.

When Julia’s arms looked like pincushions, Paul took a turn clutching the writhing cat while she snapped the picture, but he had even less luck keeping their hyperactive star calm.

After countless futile shutter clicks, they gave up on the action shot and decided on a simpler pose, Minouche’s head framed in the cat window. Julia doled out bits of raw liver and murmured in his ear to keep him from escaping before Paul was ready. They eventually got the shot, but Minouche got all the liver Julia had planned to grind into a luncheon pâté.

When Minouche waddled off for a post–photo session nap, Paul suggested Julia’s next subject should be a still life. In a letter to Charlie explaining his picture-taking philosophy, Paul referred to the cat-window episode with droll understatement: “A struggling cat is anything but simple to photograph.”

ONE MORNING A big black cat with a nasty disposition shattered the peace and quiet of la Peetch. This “monster Beeko” belonged to one of Simca’s cooking school students, who stayed in the house down the hill. Soon a feline turf war was on. Beeko crept up to the patio where Minouche lay napping and let fly a barrage of howls and screeches. Since Paul was at his outdoor easel and Julia in the kitchen nearby, Minouche stood his ground—from under a lawn chair, to be sure.

Minouche’s calm gaze infuriated Beeko even more. Paul imagined the aggressor’s rant: “I’m going to take over! Also all the food around here, and the next time ‘I’ll beat the beejeesus outa youze!’”

Beeko finally got his chance—Minouche, dozing in the sun all by himself. When the bully lunged at their kitten, Julia rushed out shrieking and waving her whisk. Paul too came running, a dripping paintbrush in one hand and palette knife in the other. Beeko tumbled backward into the thorny rosebushes and whimpered all the way home.

But it wasn’t over. Next time, the brute wised up and sneaked in under the radar before Minouche could summon the swat team. The little tiger showed spunk but got the worst of it, a nasty bite on his paw, and had to be quickly bundled off to the vet, who by now knew almost the entire la Peetch kitty corps.

The feisty Minouche had to endure house arrest while his wound healed. He paced and miaoued, and the minute his bandage came off, he leaped out his window into a driving rainstorm, oblivious to the whereabouts of his rival. Bonne chance! A lucky break for Minouche. Beeko and his owner had bid adieu to Bramafam.

Soon Julia and Paul were packing up too, heartbroken at leaving their new favorite behind. “Our poussiequette is adorable, and we simply hate to give him up—but shall return him regretfully to Bramafam Saturday evening. How can we thank you enough—comment vous dire à quel point—we have appreciated this priceless loan! Merci, merci!”

Paul worried for Minouche. What would he do without Julia, “who feeds him and talks to him and pats him, and strokes him, and kisses his head’s top-knot … if the closed kitchen window (the pussy’s exit and entrance-system) is unfriendly, and firmly shut, poor puss!” He scribbled a unique solution next to a photo of their kitty and sent it to Charlie—they could put a stamp on him and send him by airmail to Cambridge.

But mailing Minouche was wishful thinking. He’d have to settle for Simca’s warm kitchen, kisses, and cuisine until he heard JuPaulski’s Peugeot rumble up the dusty road to la Peetch once again.

JULIA’S RESPITES AT la Peetch energized her, and after several weeks of R and R, she was ready for action, merrily plunging into the next TV or writing project. For Paul, it was getting harder to pick up and move across the ocean as often as they once did. With age he became less tolerant of the Provençal heat, but New England winters were hardly more attractive. Even though France would always exert a strong pull, the sunny shores of California beckoned. So in 1981 they bought a condo on the coast near Santa Barbara where they could spend the winter months and one day retire.

For Julia, it was a kind of homecoming. Their new place was near the spot where the McWilliams family had rented a summerhouse and Julia spent carefree days on the beach. The sea breezes and rolling hills covered with olive groves, lavender, and roses felt like paradise—Provence without the hassles of overseas travel and separation from family. Paul made his last trip to la Peetch in 1986 and, with his health failing, entered a nursing home a few years later. Julia returned to their hillside hideaway several more times, but it wasn’t the same without her Paulski, and she always hurried home to be near him.

Paul once wrote, “Due to Julia’s temperament she believes that everything will always be OK everywhere, at all times.” Far from a Pollyanna, she was deeply pained by Paul’s long, slow decline but kept her sorrow to herself. She made sure he was included in her cooking demonstrations and guest appearances for as long as possible, and when he could no longer keep up, she visited, often twice a day, and faithfully phoned when she was traveling. Paul died in May 1994, and she blew a kiss as she scattered his ashes into the Atlantic near their Maine cabin.

She composed her best tribute to Paul in the 1968 French Chef Cookbook: “Paul Child, the man who is always there: porter, dishwasher, official photographer, mushroom dicer and onion chopper, editor, fish illustrator, manager, taster, idea man, resident poet, and husband.”

Though she grieved the loss of her soul mate, Julia was never one to look back. Her gaze was firmly set on the horizon, and in time she embraced a busy bicoastal life. There were more cooking shows with new partners like Jacques Pépin, books to write and promote, and galas for pet projects like the American Institute of Wine and Food, an organization born at her dinner table. She was constantly looking for new ways to spread the gospel of good food, the life mission she discovered with Paul and Minette in Paris all those years ago. In her last decades, Julia lived her favorite motto: “Boutez en avant!” (Charge ahead!)