Chapter 12

Hip-Hop vs. Soul Train

IN THE SPRING OF 1980 Curtis Walker—also known as Kurtis Blow, Harlem native, City College of New York attendee, and all of nineteen years old—stepped onto the Soul Train set for episode #336 and became the first hip-hop figure to appear on the show. The headliner was the self-contained band L.T.D., featuring deep-voiced vocalist Jeffrey Osborne, but Blow’s appearance was the highlight of the taping. Overjoyed to be on the show, the young MC performed “The Breaks” live to a track for an excited group of dancers. Then Don Cornelius walked on stage to do the customary interview. For Blow, this was to be the high point of an extraordinary day. He’d flown in that morning from New York on his first trip to the City of Angels. On the heels of his first single, “Christmas Rappin’,” and the gold “The Breaks,” Blow had already performed in Amsterdam, London, and Paris.

But for a ghetto kid from Harlem, being on Soul Train was a new pinnacle. Moreover, Blow had started his career in hip-hop as a break-dancer and had idolized Don Campbell and the Lockers. Blow had checked into his hotel that morning and then sped over to the Soul Train set, geeking out that his dressing room was right next to Fame star Irene Cara’s.

Don had been cordial when greeting Blow backstage and gave in when the rapper requested that he be allowed to perform live to track, rather than lip-synch “The Breaks,” since (a) he’d never lip-synched in his young career and (b) he needed the crowd interplay that was essential to hip-hop. When Cornelius walked on the stage, Blow expected the standard Soul Train treatment. “We know Soul Train, after the performances, and you’re standing onstage, and Don Cornelius comes out. He gives a couple of accolades: ‘How about another round of applause for this great artist.’ I’ve seen this all my life. I’m anticipating this, and I’m ready for this . . . So he comes out, you know he has the microphone, he comes up and stands next to me, and he says, ‘I don’t really know what everyone is making so much fuss about all this hip-hop, but nonetheless you heard him here, Mr. Kurtis Blow.”

The MC recalled that moment with sad clarity. “I was heartbroken. My heart actually left and traveled south to my feet, and I was stunned and shocked. And I don’t know what I said. I don’t think I said anything. I don’t know what I said, but whatever it was, believe me . . . It’s not really what I wanted to say.”

Don’s ambivalence toward hip-hop was shared by most of the black music gatekeepers of his generation, be they major-label executives, radio programmers, or R&B musicians. Hip-hop seemed to challenge the essentials of black music: the stars didn’t sing, a DJ playing records served as the band, and “songs” weren’t structured in the verse-verse-chorus-verse-bridge-verse structure of standard pop songs. Moreover, the mainstream black popular music that Cornelius—and everyone in the black music biz—was heavily invested in had been trending toward an upscale, clean-sounding, self-conscious sophistication that was reflected in clothing as well as sound. Male artists were wearing lots of eyeliner and sporting jelled hair (either Jheri curl or California curls, depending on the product’s purveyor). It was a very LA look, one the dancers on Soul Train proudly displayed.

The stripped-down (but no less codified) look coming out of New York’s hip-hop scene represented a contrast to (or perhaps an attack on) the black mainstream and the assumptions about acceptable black maleness behind them. It wasn’t simply a generation gap that separated Don from rap—though clearly that was part of it—but a disagreement about how to be “black.” In the 1970s Soul Train had promoted a liberated funkiness that took cutting-edge style into homes across the country. But from the time Blow took the Soul Train onward, Cornelius’s soulful train would be running a little behind the sonic vehicles transporting hip-hop.

Years later, Cornelius talked about Soul Train’s sometimes uneasy relationship with this new musical movement.

Cornelius: Hip-hop kind of took Soul Train by surprise because we thought it was something that might not stick, and we didn’t jump in with both feet. But apparently we had to put both feet in the pot, because young people became so committed to hip-hop, and it became the culture it is today. People look at you funny if you act like you don’t know what it is. The younger demographics will simply turn away from you because you’re making it clear to them that you don’t know what you’re doing. What’s made it beautiful in an overall sense, and why no other genre has accomplished what it has, is that hip-hop/rap are so inclusive. It’s inclusive in the sense that you don’t have to be Quincy Jones to succeed in hip-hop. There are people who have carved successful careers in the hip-hop/rap media who, thirty years ago, would not have been able to participate in the music biz. It’s part of the black culture, and if you learn to understand it, you can actually make a good living out of it.

With this pragmatic view as Don’s guide, rap artists would slowly become part of the Soul Train mix. The first performers with a huge rap hit were the Sugar Hill Gang, a trio of inexperienced MCs from the New York–New Jersey area cobbled together by Sugar Hill Records co-owner Sylvia Robinson (a former R&B crooner who’d appeared on Soul Train in 1973 with the erotic hit “Pillow Talk”). Robinson and the three MCs put together “Rapper’s Delight,” a Top Ten hit all over the globe and a massive hit in the United States. Although this landmark recording was released in 1979, the Sugar Hill Gang didn’t appear on Soul Train until a year after its debut. I believe one reason Blow was booked on the show before the Sugar Hill Gang is that he was signed to Mercury Records, a major label with a strong, ongoing relationship with Cornelius—who needed the label’s cooperation if he wanted to book its more mainstream R&B acts. Sugar Hill Records, born out of the ruins of R&B All Platinum Records, out of Englewood, New Jersey, was an independent label with no such leverage.

“I guess he was hesitant with bringing [hip-hop] on,” recalled Sugar Hill Gang member Big Bank Hank. “But you can’t stop a hit . . . If you can’t stop it, you might as well get out of the way, because here it comes. It was like you were riding the perfect wave.”

A reflection of Sugar Hill’s absence of clout was that neither the group’s three members nor its management were able to persuade Cornelius to drop his lip-synch policy. Where Blow was able to perform live, the trio was forced to lip-synch its performance. “Hip-hop is about being able to flow and rhythmically go in and out of the music and change it whenever you want to. Now you’re stuck because you have to go with what the track is. You can’t play with the music.” Still, the performance went well. “Oh, they lost their mind,” Hank recalled. “They just loved it.”

As the eighties unfolded and rap began its long progression from New York underground culture to mainstream brand machine, Soul Train would showcase top MCs overwhelmingly from New York and elsewhere on the East Coast: everyone from Run-D.M.C. to LL Cool J to Whodini to the Beastie Boys. But several of the artists felt a chill from Cornelius and some of the Soul Train staffers. Members of Run-D.M.C. would, incredibly, tell reporters that they felt more welcome at their initial visit to American Bandstand than they did on Soul Train.

Ahmir Thompson, an ardent Soul Train viewer and future hip-hop icon himself, remembers these appearances well. “I’m glad that it was included, but I more or less felt that maybe it was tokenism. Maybe it’s kind of hard to see change.” He felt that a lot of the tone of Cornelius’s interaction with rappers during the 1980s was “standoffish” and along the lines of “How long do you think this is gonna last?” Thompson knew this attitude well, since “that’s how my father was: ‘That’s not music.’ He would always cover his ears. I’m glad it was included because, again, my first view of the Sugar Hill Gang or Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five was on Soul Train . . . I could tell that Don was a little uncomfortable in embracing it, but as a businessman, I’m glad he was smart enough to give in.”

If Cornelius tolerated the New York MCs for whom boasting about their rhyme skills was the essential topic, he was actively hostile toward the crack-era narratives that gained popularity around 1989 and, ironically, came out of some of the same South Central Los Angeles communities (Compton, Long Beach, Inglewood) as the majority of his dancers. Led by Ice-T, N.W.A, Snoop Doggy Dogg, Warren G, and Tupac Shakur and built primarily on samples from funk bands, this genre became a cultural-commercial phenomenon that initially didn’t need radio play to sell records, but by 1994 it found its obscenity-free singles and party-hardy videos landing in heavy rotation—not just on black radio and BET, but on MTV as well.

Moreover, the charisma of the star gangsta rappers, plus the tabloid violence of the crack era, led many of them to star in Hollywood features (New Jack City, Boyz N the Hood, Menace II Society, Trespass, Juice) that generated platinum-selling soundtracks. By 1994 the ubiquity of these performers, as well as their drug-referenced, blood-splattered, sexually raw (and often sexist) records, outraged many.

Spurred by activist C. Delores Tucker and other elders in the black community, on February 11, 1994, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Consumer Protection, and Competitiveness of the Committee on Energy and Commerce in the House of Representatives held the first of two hearings on whether there should be a ratings system for recorded music. While lip service was given to sexism and violence in rock, hip-hop was the clear target of the hearings. I was there that day to give historical context on the music and to support free speech in music.

Don Cornelius was there, too. We spoke briefly at the hearings, but it was a strained conversation because he was there to attack gangsta rap and support a mandatory ratings system for all music. I’m reprinting Cornelius’s testimony in full because I think it perfectly captures the ambivalence of the R&B establishment’s feelings about hip-hop in general and gangsta rap in particular during the nineties.

In order to understand the ever-growing popularity of the music form known as Gangsta Rap, it is necessary to briefly explore rap music in general and some of the reasons why rap has become the musical entertainment preference of many millions of youth and young adults throughout the free world. Originally intended as a purely entertaining form of street and night club or dance club rhyming or poetry spoken over prerecorded music tracks, rap music has evolved into a legitimate, popular music art form through which many young musicians, publicists and recorded music producers who are connected, often sociologically to America’s underclass (particularly that segment which is African-American), are able to express various kinds of commentary on some of the harder realities of life as it exists in many of America’s African-American ghettos.

The preponderance of recorded rap music which deals with ghetto life is likely to include extremely profane lyrics which tend to glorify violence or illegal firearms or drug use. The lyrics which are degrading or disrespectful to women, or sexually explicit lyrics. This kind of rap has become widely known as “hard core” rap. Rap artists who specialize in hard core are well aware going in that hard core records, for obvious reasons, get no radio station airplay whatsoever, which would literally be the kiss of death for any other recording artist. This is usually not the fate, however, in the case of hard core rappers, thanks to what is known as the “underground” retailing market, a random array of small, independent record stores located usually in urban areas of the United States and specializing (at least partly) in hard core rap records which are sold mostly through word of mouth.

It was eventually determined that the harder the core of an underground rap record, the bigger the unit sales and the more income the artist and the record label would earn. The underground record market established the fact that there exists an enormous audience (comprised mostly of youthful record buyers) which apparently enjoys hard core rap. Moreover, this consumer group is not limited to African-American youth who live in America’s African-American ghettos. Record industry sales research indicates that roughly sixty percent of all rap records sold are bought by whites. The form known as Gangsta Rap is a relatively recent spin-off of basic hard core. Gangsta Rap lyrics tend to glorify or glamorize rebelliousness, defiance of the law or various forms of street “hustling” in the minds of the listeners, much the same way as being “hard” and “tough” has historically been and still is being glamorized in the movies and often times on television.

As to the question: “Why would African-American youth be so receptive to the marketing of hard core and Gangsta Rap and the messages within?” I would ask: “Why wouldn’t African-American youth pay attention to artists who seem to fully understand the lifestyle problems that African-American youth face. And why wouldn’t African-American youth be anxious to listen to recording artists who are willing to openly discuss and dramatize many of these dire problems within the context of their records?” Please keep in mind that, for the most part, these are African-American youth for whom America has shown no real concern—at least during the past decade or more. These are African-American youth in whom our country has invested very little over the past decade in terms of channeling economic assistance and better training and education.

Over the last decade, our country has invested almost nothing toward creating the kinds of opportunity which would allow such citizens to eventually better their lives, their surroundings and ultimately their futures as Americans. I tend to wonder if we shouldn’t be far more concerned about eliminating poverty, violence, despair and hopelessness from low income African-American communities than about eliminating Gangsta Rap. In spite of its many critics and detractors, rap music has, indeed, been very effective and in some ways a Godsend in providing entertainment relief and in many cases economic relief to a largely forgotten community. On the other hand, it goes without saying that anyone who sells any form of entertainment which is either anti-social or illegal in nature and cannot be indulged in except behind closed doors, is engaged in what could be defined as pandering. This same standard should also apply regarding hard core or Gangsta Rap.

Therefore, any recording artist or record label who creates or sells any record which is anti-social, profane, violent or sexually explicit in nature to such a degree that it cannot be listened to in public without offending others or cannot be listened to by youthful fans of such music in the presence of an adult authority figure, in a certain sense, is also engaged in pandering. I recently heard a well known Gangsta rapper explain his philosophy during a TV interview. He said, “I make music for poor people and there are far more poor people than rich people! So, as long as I satisfy poor people, I’ll always have a job!”

I viewed this explanation as quite intelligent and well thought out; but clearly a case of pandering to the naivete of youthful record buyers who are intrigued by anti-social commentary. At this time I am not prepared to say which is more perverse between pandering by certain political ideologues who do it to appease those who are turned on by pro–law and order, anti-urban development, anti-welfare and tax cutting rhetoric or pandering by recording artists and record companies to youth who think it’s hip to listen to Gangsta Rap. If I were asked, “Should governmental steps be taken to curtail hard core or Gangsta Rap; or to clean up rap lyrics; or to make recording artists or record companies pandering to the rebelliousness of youth illegal,” I would say no to all three. Consumer pandering within reason is, of course, an accepted practice in America with respect to entertainment distribution. Movie studios and home video movie distributors openly pander to customers who enjoy somewhat anti-social or sexually explicit entertainment.

Most major distributors of such entertainment do, however, exercise a reasonable degree of social responsibility through the almost universal use of a well designed rating system. Rap music does not need to be censored. Rap music and all other recordings do need to be rated just as movies are. Records by recording artists which are violently or sexually explicit or which promote illegal (drug or firearm use or and other anti-social behavior) should be clearly marked and identified “X-rated.” The “parental guidance” sticker system presently being used in the recording industry is simply not enough. The MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) rating system allowed the movie industry to separate exploiters and panderers from legitimately creative filmmakers. The same result can occur with regard to the music industry with the support and participation of the RIAA (Record Industry Association of America).

As the situation now stands, there is no real stigma attached to the creation, marketing or advertising of a profane or anti-social record or LP. Individuals and companies which now openly pander to youth consumers who are attracted to anti-social recorded product would market such product with far less pride of accomplishment in the face of a strong rating system. A strong rating system will also place somewhat of a stigma on consumer ownership of such product regardless of the consumer’s age. While a rating system may not completely solve all of the problems concerning hard core or Gangsta Rap recordings, such a process may be well worth considering as a place to begin. Thank you.

A blowup of the sexually suggestive cartoon album cover to Snoop’s 1993 album Doggystyle was on a stand, an illustration of the nastiness that gangsta rap represented. Despite Cornelius’s harsh words for gangsta rap, Snoop Dogg never lost his love for Soul Train. When asked about the show’s impact on him growing up in Long Beach, Snoop had a unique perspective. He said, “A lot of my homies, when we go to jail, we measure our time by how many Soul Trains you got left. I got my five Soul Trains. That means you’re getting out in five weeks. I got seven Soul Trains left—I’m getting out in seven weeks. As sad as it is, it was a good feeling because when you in jail, you had to have something to keep you up, and Soul Train kept a lot of brothers up. That was the main effect they had on Long Beach that I remember.”

It was just this kind of jailhouse perspective that made gangsta rap popular and everyone in the black music mainstream uncomfortable. But Cornelius, being a businessman, would have Snoop on episode #743 in 1993 to perform “What’s My Name” from that same Doggystyle album, which won best album at the 1994 Soul Train Awards. Snoop made a very heartfelt tribute to the show: “I ain’t mad ’cause I didn’t win no Grammy. This is the black folks’ Grammys!”

Throughout the late 1980s and beyond, those clean versions of rap songs by Snoop and others made it possible for Soul Train, as well as radio stations, to play some of the hooky but hard-core rap hits of the day. But true hip-hop fans knew that what they heard on TV was the watered-down version, and that the lip-synched performances on the show were inferior to the kinetic music videos in rotation on MTV, BET, and elsewhere. Don’s discomfort with gangsta rap haunted the show, so despite its commercial viability, its graphic content really made it inappropriate daytime-TV fare. This wasn’t the O’Jays or Al Green. The times had changed. Hip-hop wasn’t Cornelius’s music and never would be.

DANCER PROFILE: Rosie Perez

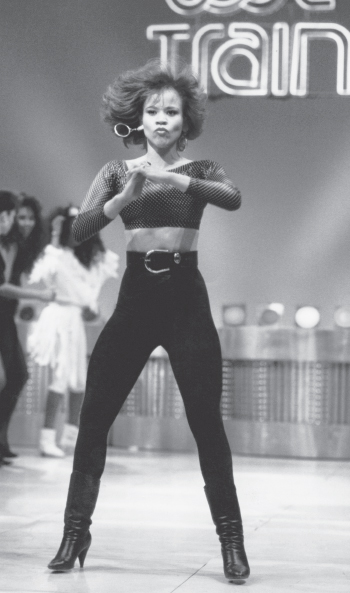

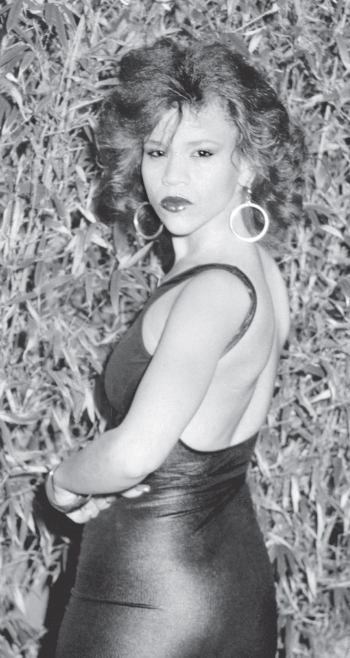

Rosie Perez came out to sun-kissed California from Bushwick, Brooklyn, a burnt-out, impoverished neighborhood in a tattered borough, bringing a fierce warrior attitude that was reflected in her take-no-prisoners dancing. Short and curvy with reddish hair, pouty lips, and a high-pitched voice with a thick Nuyorican accent, Perez was a unique and, to some, disquieting presence on the Soul Train set.

“Rosie came on the show, and she was just so hot and so sexy,” Crystal McCarey said. “That girl could dance. She could move. You know, females will be females. They’re catty. When Rosie came, I think that some of the other dancers were a bit intimidated, and they weren’t friendly or kind to her.”

McCarey befriended the new girl and advised her not to worry about what the other dancers thought of her. “Rosie was a very sweet lady, but she was one hell of a dancer. I would have to say that I thought I was hot stuff, too, but when I saw Rosie, I was like, Oh, my goodness. She got that fire.”

It wasn’t only women who had complicated feelings about the Brooklynite. The Cutty mack himself, Louie “Ski” Carr, would sometimes let Rosie and some other dancers stay at his apartment on weekends Soul Train was taped. “Her girls and her used to change, sleep over, and go to the next show,” Carr said. That sense of fellowship didn’t always translate to the studio. “We was cool, but on the Train it was a chance to just be yourself and do your thing. She was doing her thing, and I was doing my thing. There’s actual footage of us boogying and having that friendly competitiveness. Rosie was aggressive and sexy and a little street, like a machine gun. Just do her move strong. Men love strong women, plus she’s beautiful.”

Rosie Perez’s fierce New York–styled dancing made her an immediate fan favorite.

Perez’s Soul Train career began, like so many others, at a Los Angeles nightclub. The nineteen-year-old had initially come west to help a struggling cousin with her two young children. When that arrangement proved too stressful, Rosie began working part-time jobs while attending classes in three different LA-area universities as a biochemistry major. She got some stability when she landed a job working as secretary and babysitter for the family behind Golden Bird fried chicken.

Along with some girlfriends, Rosie was at a club called Florentine Gardens when Chuck Johnson inquired if she’d like to be on the show. Skeptical New Yorker to her core, Rosie replied, “Yeah, right.” Johnson said, “No, really,” and handed her his card. She remembers standing on the floor at Florentine Gardens “screaming my head off. I was like, Ahhh! To be so young and being a teenager, being asked to go on Soul Train, it was just—it was mind-blowing. He said, Will you come, will you show up on Saturday? I said, Can my girlfriends come? And he said, What do they look like? I thought that was so rude. Thank God they were hot. So we all got to go, and that’s how I got on Soul Train.”

“The first time I went on,” she continued, “it was bittersweet because I did not know that we were going to be waiting outside of the gates of the studio and jockeying for position. I was like, ‘Oh, we’re outta here.’ We were about to leave. The talent scout from Soul Train was like, ‘No, no, no, you, short one. Come in.’ I said, ‘Well, I’m not coming unless all my girlfriends get in.’ That was great, but it wasn’t great for me because he let us in, we didn’t have to wait on line. So when the rest of the people came in, instant hatred. It was really crazy.” That introduction to the show was likely the root of the disdain McCarey spoke about. “There was really great people,” Perez said, “but there were a few that were real bitter.”

Like most popular Soul Train dancers, Rosie Perez was the toast of LA parties.

Perez, who had come from a New York City street dance aesthetic where unisex sportswear was the norm, arrived at the studio in jeans, sneakers, and a T-shirt, and staffers told her it wasn’t proper Soul Train attire. Instead they pointed out a girl in a super-short dress. Rosie had wisely brought a sexier change of clothes. Not only did they like what she’d changed into, but the producers immediately placed Rosie on a riser, where the camera was sure to find her.

Don selected Perez to do the Soul Train scramble board, yet another honor for the novice. When Rosie spoke in that now famous Brooklyn-meets–Puerto Rico accent the host asked her, “Is that how you really talk?” Embarrassed, Perez did her best to lose the accent. Perez’s good fortune, not having to wait in line and getting a riser spot on her first day, made the New Yorker a target for some old heads on the set.

Perez: I think that the girls were jealous because of that. We were all very, very young. Not only the girls there were jealous. There was also boys that were jealous, and these were people who saw Soul Train as a springboard to further success. I did not view it that way. I just viewed it as “Oh my God, we’re on Soul Train!” In hindsight I understood why they were jealous. I don’t know if it was jealous as much as angry, because they were on Soul Train for years and years and years, and these kids, they used to practice for hours, their dance moves, their dance routines, what they were gonna do going down the Soul Train line. They would spend hours picking out their outfits.

Though viewers and other dancers characterize Perez as an aggressive dancer, she feels that she held back while on the show.

Perez: Don Cornelius did not want to see how I really danced—I was doing hip-hop, and it was foreign to people out in California. They only knew about popping and locking, so they were not keen on hip-hop dancing. Don was like, “No, no, no. You’re a girl.” I was like, What? This is really weird. Then I had to dance in high heels, and I never danced in high heels before, and I had this little tiny short dress, and it’s riding up my ass and I’m like, Oh my God. I couldn’t move. As you can see from the tapes, I had absolutely no style whatsoever on that show. The first couple of times, I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I was just excited and nervous and scared and just elated. That was my style. A bunch of nerves just oozing out of my body.

Whenever Rosie was in doubt about her moves, she would “face dance, just face dance. Face dance means you don’t know what the hell the rest of your body was doing but your face is fierce. That’s face dancing.” Perez is much harder on herself than she needs to be. Anyone who saw her on Soul Train was impressed with her dancing. Most people who remember her from the show usually recall her dancing in either a red or black dress. That wasn’t part of any plan. They were just the only dressy clothes this college student owned.

“Your attire had to feel like you were going to a nightclub,” Perez said. “That’s the look that they wanted, and they wanted high fashion, which I did not offer because I could only afford a dress that had that much material. I was very proud of my body back then. That’s the other thing I loved. I was hot. It’s good, it’s on tape forever. Yeah, you look like you were having a night out. That was another great thing about Soul Train. I have a picture of all of us going to a club with my friends from Soul Train. All the girls just going out to a nightclub, and we’re all dressed like we were dressed on Soul Train. It was the most surreal experience for me because I walk into the club with them and people started screaming. ‘Oh my God! It’s the Soul Train dancers!’ It was really weird.”

When you see Rosie in Soul Train footage on YouTube, she is coming down the Soul Train line like an unleashed tiger. Her first time down the line was, for her, the most memorable:

Perez: I was hysterical. My heart was pounding. I didn’t know what I was going to do. A lot of the dancers already had their routine worked out ahead of time, and I’m just freaking out. I don’t know what to do, and then you stand at the head of the line, and then, and the stage manager goes, “Go!” It was ridiculous, it was so bad. My girlfriends were cracking up at me because I’m hilarious, and I have a great sense of humor. I was laughing at myself. By the time I got to the end of the line, I was just in hysterics. I was laughing so hard, and Don Cornelius goes, “Do it again.” What? “Do it again. Put her up at the head of the line.” And I thought I had messed up, so I did something different and Don goes, “No, no, no, do it again. Do exactly what you did the first time.”

What Perez thought was silly Don loved, which speaks to their difference in perspective about what good dancing was.

Much like Jody Watley and other popular Soul Train dancers, her sudden TV celebrity led to a lot of real-world hostility. “I used to get recognized quite often as being a Soul Train dancer,” Rosie said. “Quite often. Which was great at times but sometimes was not so great. Especially back at college it was not so great. It was pretty tough.”

A turning point in her relationship with Soul Train came when Don tried to recruit Perez into a female vocal trio along with Cheryl Song and a white dancer-singer. “I told Don I could carry a tune, but I couldn’t sing sing, you know. He told me, ‘It’s irrelevant the way you sing. What’s relevant is the way you dance and the way you wear your clothes.’ ” That didn’t exactly charm Perez. Nor did the fact that when he handed her a contract, she was told not to contact an attorney. No negotiation. He wanted her to sign the contract immediately. On the heels of multicultural hit making by the Mary Jane Girls and Vanity 6, Cornelius was clearly seeing Perez and company as a solid bet.

But she still refused to sign the deal, so in an attempt to woo her, Don took her out to dinner. A business meal turned social as, for the first time, he inquired about her background and family. “What broke the ice was that when we sat down, I didn’t know which fork to use,” Perez recalled with a laugh. “Don said, ‘Work outside in.’ And then he cracked up. I cracked up, too. It was the first time I saw him laugh.” The duo had a lovely meal except for one thing—Perez still wouldn’t sign the contract.

That cordial meal was followed by a tense taping in which the host stopped Perez “three or four times” as she grooved down the Soul Train line. Unlike her first time, when Don made her go back, his tone was harsh. During a break, the two had a confrontation over the record deal and, according to Perez, she tossed one of the handy fried chicken boxes at him and stormed off the soundstage. That was the last time she’d dance on the show.

But this dustup with Don wouldn’t be the end of Perez’s relationship with Soul Train. About a year before Rosie was banned from dancing on the show, Louil Silas, a vice president for R&B A&R at MCA Records, was visiting the show with an artist when he spotted Rosie dancing in a corner by herself.

“I was on the side and I started dancing hip-hop,” Rosie said. “Louil came over and said, ‘What’s that dance? What is that? What are you doing right there?’ I said, ‘Oh, that’s hip-hop.’ He goes, ‘Hip-hop, hip-hop, cool. Yeah, that’s what I want.’ I said, ‘Huh?’ He said, ‘Bobby Brown [of New Edition] is going solo. I want you to teach him that.’ I said, ‘I’m not a choreographer.’ He goes, ‘I’ll pay you sixteen hundred dollars.’ I go, ‘I’ll be there on Monday.’ That was the beginning of my choreography career. That’s how it all started. It started from Soul Train.”

In the mid- to late eighties, when hip-hop-bred dance moves from the East Coast began to overturn the West Coast styles popularized on Soul Train in the seventies, Perez became a bridge between the two worlds. Videos were slowly beginning to replace Soul Train as the place where new dances went national. Bobby Brown, probably a more gifted dancer than singer, was the first of many acts Perez began choreographing for videos, TV appearances, and tours.

After working with Brown, she designed steps for kiddie group the Boys, the agile rapper Heavy D of Heavy D and the Boyz, LL Cool J, and new jack swing groups Today and Wreckx-n-Effect. She even worked with the ultimate diva, Diana Ross. But the gig that put her career over the top was selecting and choreographing the Fly Girls for Keenen Ivory Wayans’s sketch comedy show In Living Color on Fox. On the show, which debuted in April 1990, the four dancers under Rosie’s guidance became the new cutting edge of urban dance. It was the peak of her career as a choreographer.

“I was busy,” Perez recalled fondly. “I had a great career, and it all stemmed from being on Soul Train, which is crazy. It’s really, really crazy.”

That’s how her Soul Train story comes full circle. As a choreographer, Perez became an occasional visitor to the set, aiding artists she was working with on steps for their TV appearance. At first Cornelius was prickly, and later he just ignored her. A few years later, after her acting in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and working on In Living Color, the two ran into each other in the tunnel underneath an LA concert venue. At first Perez ignored him, but he called out to her.

“I apologized for tossing the chicken at him,” Perez said, “and I thanked him for giving me such a great platform. He told me how talented I was and how proud he was of me. We hugged and smiled. I saw the guy from our dinner at that moment. Then he told me not to tell anyone about it: ‘After all, I have an image to maintain.’ ”