TO RENDER LESS GREEK?

TRANSLATION

How on earth do you translate a crossword puzzle?

You might wonder why anyone would ever translate a crossword clue, but some people have to. Take the scene in The West Wing where President Jed Bartlet calls out a clue to the First Lady: “It may be bitter (3).” He considers TEA, makes a wisecrack that WOMAN doesn’t fit, and his wife, Abbey, rebukes him: “END, you idiot, bitter END.”

In the DVD’s French subtitles, this becomes “Peut être amer,” with a letter count of three. This is fine for THÉ, the French for tea, and FEMME still doesn’t fit, but the translator has Abbey offer RIRE as the correct answer. It’s a plausible answer—“rire amer” meaning “bitter laugh”—except that it’s too long. Faced with the challenge of finding two same-length words that might fit (or even making it a four-letter answer and having Jed say “THÉ is too short, but FEMME is too long”), the translation runs away and hides.

The Swedish and Norwegian subtitles are even more cowardly, removing Abbey’s line altogether. It’s a shame, since the words are not random: The important ones are END (foreshadowing Abbey’s agonizing investigation for medical misconduct) and WOMAN (because Jed has been impatient with Abbey’s indecision over earrings). TEA is the least important word in the exchange and certainly isn’t the one to base the translation’s letter count on.

And if that seems like an involved process for a throwaway gag at the top of an episode of a TV program, consider the challenge of translating something larger. What if the material in a fictional crossword was more important? What if wordplay was part of the original text?

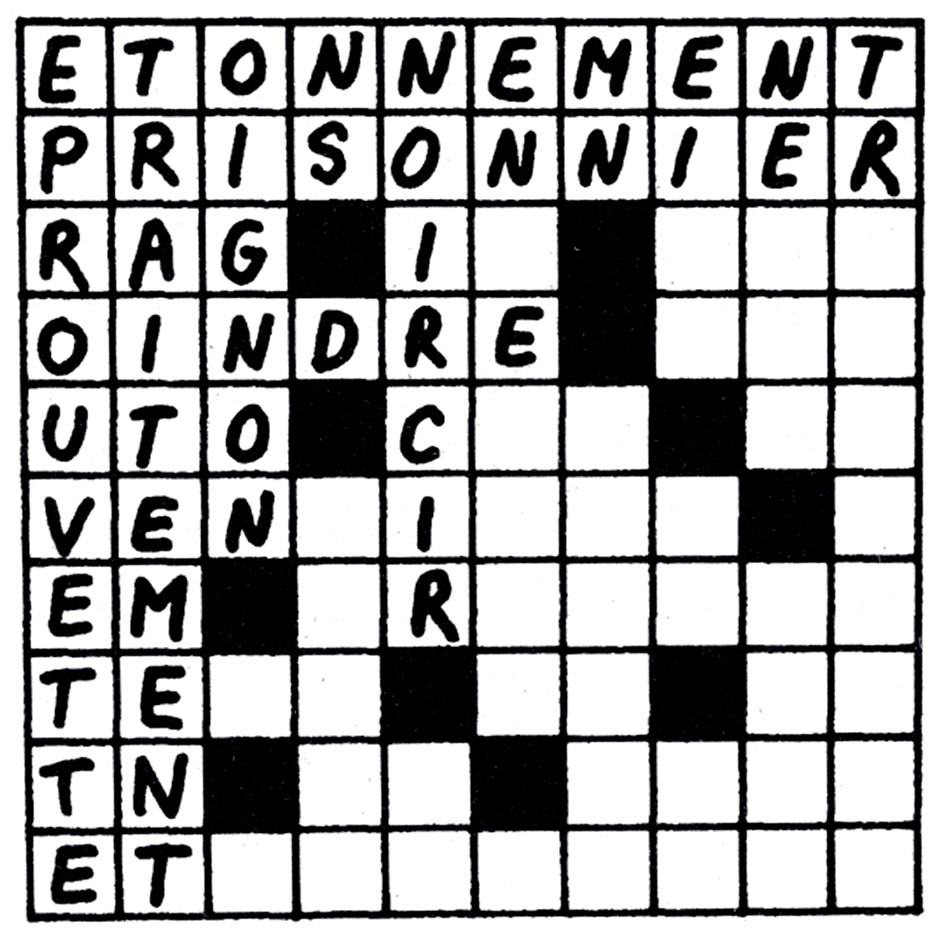

In Georges Perec’s French-language novel La Vie mode d’emploi, we find an unfinished puzzle in the room of one of the characters reproduced in the text. The rest of the book is riddled with cross-references, puns, and hidden expressions, so the task facing the translator is daunting: How do you re-create a collection of words, preserving not only their meaning but also the characteristics that allow them to intersect with one another in a grid? And since a seasoned solver might look at the grid and wonder which words might fit the empty spaces, should the gaps be taken into consideration, too?

Happily, Perec was aware of this potential problem and furnished his German translator Eugen Helmlé with notes about the novel’s wordplay. In the case of the crossword, his instructions were that only ETONNEMENT and OIGNON mattered. And so, in David Bellos’s English translation, we see ASTONISHED and ONION among other unrelated words. Bellos told me that the inclusion of a potential TLON in his version of this fictional puzzle is a nod to the imaginary world in the title of Jorge Luis Borges’s “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” which seems a suitably perécienne flourish.

He added a regret about his translation of the grid: The placement of ONION means that there’s an impossible entry ending with O in the English version of the grid. So if you have a copy of Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual, you should pull out a pencil and add an extra black square to the grid, in this case in the space immediately following ONION.

And if you’re an experimental novelist with, for whatever reason, a grudge against translators, you might consider creating a book featuring a puzzle in which the clues, the entries, and the way they intersect are vital to the plot. A translation of the grid would be likely to necessitate a different grid, and vice versa. As Bellos remarked, “It would be a paradoxical and fuse-blowing project.”

(In the interests of sanity, then, let’s stick to our native tongue. Ah, but if only it were that simple. Are we talking about English as she was written in poetry and prose, where every word has a long and distinguished history, or as she is spoken, where new words appear as if from nowhere . . . ?)