THE LATEST, FROM ALL CORNERS OF THE GLOBE?

NEWS

How the news can dribble into the puzzle

Very often, the crossword becomes news. One morning at the Scott Lithgow shipyard in Scotland in 1981, two welders were tackling the Financial Times crossword while they waited for a welding rod to be repaired; a manager told them to put away the puzzle, and when they refused, both were suspended. Following a disciplinary hearing during which they apologized, one was further suspended and the other sacked, and their fellow shipbuilders went on strike in solidarity.

This local incident was reported in the national press, and it wasn’t pegged as an industrial-relations report. The tone was one of incredulity. Welders tackling a cryptic crossword? And in the posh people’s Financial Times, at that? In the 1980s the perception of a class divide was still very strong: Quick crosswords in tabloids were for the workers; cryptics were for those who had had a classical education.

And sometimes, the travel is in the other direction: from the news part of the newspaper into the puzzle. Happily, this is seldom. The puzzle provides a haven for anyone who has bought a newspaper and then realized that there is something unbearable about current affairs and a comfort of abstraction in the sturdy reliable grid.

This is put most succinctly by Joan Didion in her study of bereavement, The Year of Magical Thinking, when she describes going straight from the front page of The New York Times to the puzzle page:

...a way of starting the day that had become during those months a pattern, the way I had come to read, or more to the point not to read, the paper.

The flip side is that when the puzzle does reflect what’s going on among the other pages, the effect can be magical in a different sense. The greatest example is best told in reverse chronological order.

January 2004, Butler University, Indiana: Mathematics professor Jerry Farrell takes part in an online interview. After discussing a puzzle he wrote in 1996, he shares with his interviewer a special “telekinesis puzzle” he has since constructed. The solver begins by tossing a coin. Heads or tails?

November 6, 1996, a newspaper kiosk in New York City: The lead story in the newspaper is CLINTON ELECTED.

November 5, 1996, the office of the New York Times puzzle editor: The phone rings. It is a crossword solver, angry that puzzle editor Will Shortz has been using the New York Times crossword to promote his personal political views. It rings again. Another solver is infuriated by Shortz’s presumption in predicting the outcome of the fifty-third presidential election. It is polling day and the votes have not yet all been cast, let alone counted. The phone continues to ring . . .

Earlier that morning, in the home of a New York Times solver: Outside, people are heading to the polling stations to cast a vote for Bob Dole or Bill Clinton (or, indeed for Ross Perot or Ralph Nader). Inside, the solver looks at the day’s puzzle in The New York Times. She fills the third row from the top with the answer to 17 across’s “Forecast”—PROGNOSTICATION—and then the third row from the bottom with MISTERPRESIDENT, which directs her to the middle row. This row has two clues, both of them unusual:

39A. Lead story in tomorrow’s newspaper (!), with 43A

43A. See 39A

Forty-three across is clear from the crossing letters: ELECTED. The solver frowns. Tomorrow’s newspaper will of course lead on the victory of whoever is elected, but there’s no way that headline, with the name of the victor, can be an entry in today’s puzzle. Surely that’s not the PROGNOSTICATION?

It is. The down clues that cross with 39 across spell it out: CAT (“Black Halloween animal”), LUI (“French 101 word”), IRA (“Provider of support, for short”), YARN (“Sewing shop purchase”), BITS (“Short writings”), BOAST (“Trumpet”), and NRA (“Much-debated political inits.”). The middle row reads: CLINTONELECTED. The solver picks up the telephone.

Earlier that morning, in the home of another New York Times solver: Another solver frowns at the grid. “Lead story in tomorrow’s newspaper?” He fills in the squares of 39 across with help from the down clues: BAT (“Black Halloween animal”), OUI (“French 101 word”), BRA (“Provider of support, for short”), YARD (“Sewing shop purchase”), BIOS (“Short writings”), BLAST (“Trumpet”), and ERA (“Much-debated political inits.”). The middle row reads: BOBDOLEELECTED. The solver picks up the telephone.

Earlier that year: The candidates in the forthcoming election are confirmed as Bob Dole and Bill Clinton (and Ross Perot and Ralph Nader). A math professor and occasional puzzle constructor named Jerry Farrell asks New York Times puzzle editor Will Shortz if he remembers the puzzle that Farrell submitted to the paper in 1980. Shortz does.

1980, the offices of Games magazine: Games editor Will Shortz receives a crossword puzzle that has been rejected by The New York Times. He thinks it is “pretty amazing” but can’t accept it as it is beyond the deadline for the November/December issue and the puzzle needs to be published before Election Day on November 4.

Earlier that year, the office of the New York Times puzzle editor: New York Times puzzle editor Eugene T. Maleska receives a puzzle from math professor and occasional puzzle constructor Jerry Farrell in which the entries that intersect with 1 across are devised such that the first answer in the grid can equally validly take CARTER or REAGAN, clued as the winner of the forthcoming election. He rejects the puzzle, asking, “What if Anderson wins?” Maleska has been in the post for three years but already has a reputation for fastidiousness and fustiness. It is unclear whether his rejection is motivated by a conviction that independent candidate John B. Anderson might break the two-party stranglehold on American politics, by a sense of loyalty to another man who uses a middle initial, or by a sense that The New York Times is not in the business of provoking solvers and messing with political crystal balls . . . and never will be.

So much for continuity. Here, in the same spirit, is Jerry Farrell’s telekinesis puzzle (answers in the Resources section at the end of the book):

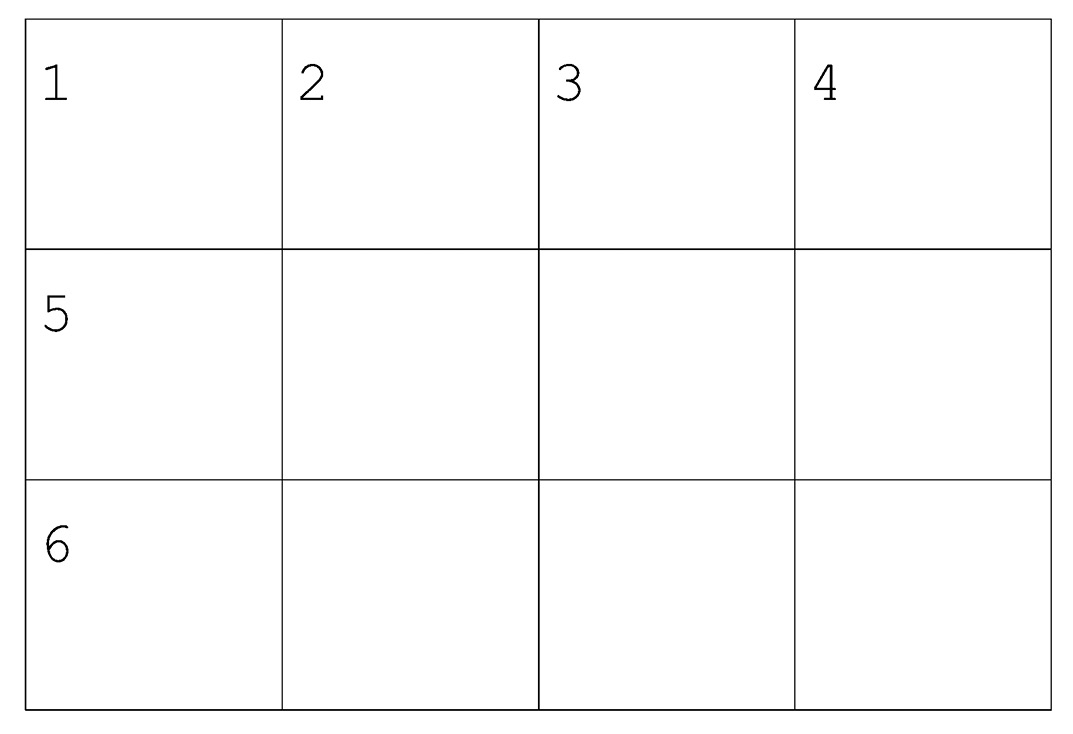

The solver begins by tossing a coin and writing HEAD or TAIL as 1 across in a four-by-three grid.

|

Across |

Down |

|

|

|

1 Your coin shows a |

1 Half a laugh |

|

|

5 Wagner’s earth goddess |

2 Station terminus? |

|

|

6 Word with one or green |

3 Dec follower? |

|

|

4 Certain male |

Postscript: On July 9, 2003, a New York Times puzzle by Patrick Merrell had at 20 across TOURDEFRANCE and at 35 across “[Prediction] Lance Armstrong at the end of the 2003 20-Across”: Both FOURTIMECHAMP and FIVETIMECHAMP were valid entries, and the first letters of the first seven clues spelled out F-A-R-R-E-L-L, an appropriately arcane accolade.

(The CLINTON/BOBDOLE puzzle is treasured by American solvers. Its equivalent in the UK is a puzzle that contains the clue “Poetical scene with surprisingly chaste Lord Archer vegetating [3, 3, 8, 12].” If that means nothing to you, you are not alone. It is time to take a peek at the British cryptic and its celebration of sometimes baffling wordplay. Let’s start with an example of the British love of mucking about with language . . .)