THE SOUND OF WEBSTER’S, UP TO A POINT?

ADDICTION

When crosswords prove too much of a distraction

In the wine-themed road trip movie Sideways, we see Miles Raymond solve—in pen—two real-word New York Times puzzles, set by Alan Arbesfeld and Craig Kasper. The viewer is taken aback by the incorrigible Miles’s drink-driving, but that pales into insignificance when we see him indulging in a spot of what might be termed solve-driving. Here is a man with some unusual priorities. Miles is not, though, cinema’s greatest exemplar of the Man Who Loves Puzzles Too Much.

For that, we turn instead to the classic British weepie Brief Encounter, its screenplay written by Noël Coward and based on his one-act play Still Life. In the stage version, housewife Laura Jesson is tempted to enter into an extramarital affair with charming physician Alec Harvey and all the action takes place in the refreshment room of Milford Junction railway station.

The screen adaptation shows us Laura’s home life. Crucially, her husband, Fred, is not portrayed as a monster; neither is Dr. Harvey a baddie. No, Fred is a kind and decent man: The villain in Brief Encounter is a crossword.

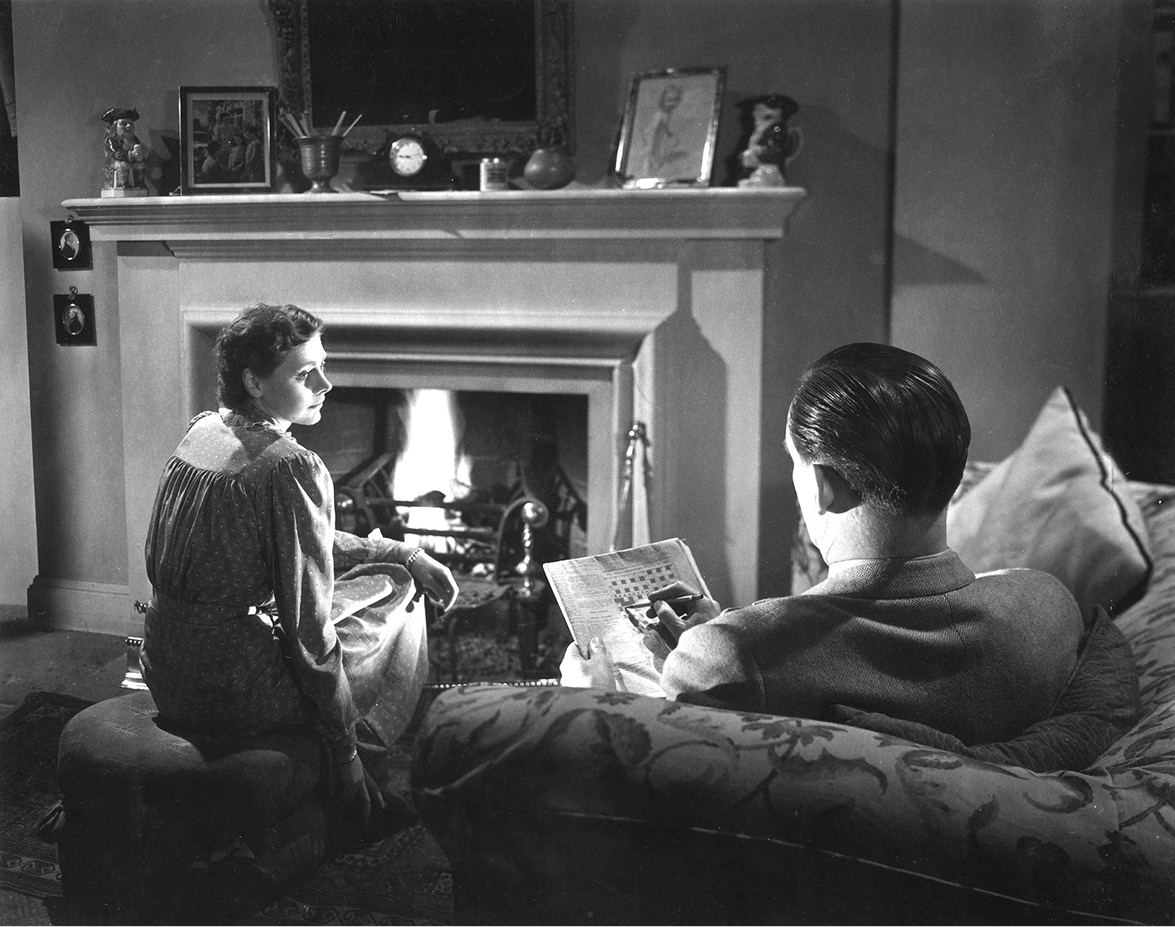

Consider the first time we see the married couple together. Fred invites Laura to sit by the fire and help him with the Times crossword; she replies that he has the most peculiar ideas of relaxation.

“Fred,” mutters the viewer, “can’t you see that your wife is forcing that smile? The last thing she wants is to listen to you calling out clues.” Yet, in the very next scene, he asks Laura to complete the Keats line “When I behold, upon the night’s starr’d face, huge cloudy symbols of a high . . .”

With an effort, Laura gives the answer, ROMANCE, and suggests that Fred check it in The Oxford Book of English Verse—he doesn’t: He’s satisfied because it fits with the entries DELIRIUM and BALUCHISTAN.

“Romance!” barks the viewer. “Romance, Fred, you damned fool! Not the word ‘romance’; not the seven-letter string R-O -M-A-N-C-E: It’s the real thing your wife is crying out for!”

Here the film declares that crosswords are a retreat from the world and from feeling—an abstraction perhaps not dangerous in itself but to be feared in that it ultimately sends respectable wives into the arms of strangers in railway refreshment rooms.

“And is it any wonder?” yells the viewer, now distraught. “I’ll tell you who wouldn’t spend time with Laura working out which words fit with BALUCHISTAN. Dr. Alec Harvey, that’s who. The Dr. Alec Harvey who’s been making her faint, that’s who. Out-of-season rowing in astonishing scenes in a botanical garden is Alec’s idea of fun, being stranded in the water, helpless with laughter—not filling a monotone grid with the names of Pakistani provinces.”

And it gets worse. One evening Laura blurts out that she had lunch earlier with a strange man, and that he took her to the movies. Concentrating on his puzzle, Fred replies, “Good for you,” and goes back to pondering who said, “My kingdom for a horse.”

Such is the grip of the puzzle on Fred’s mind that he moves on to his next clue rather than addressing the reality of his marriage crumbling in front of him. Just as Scarface had cocaine and Trainspotting had heroin, so Brief Encounter shows the harrowing effects of crossword addiction.

“For God’s sake, Fred!” the viewer is by now howling. “Put down that newspaper and hold her in your arms!”

Happily, in the closing scene, he does. It is only as the picture ends that we see the villain—this scourge of respectable middle-class marriage, this divisive word game—vanquished. Laura’s anguish is so intense that Fred, finally, lets go of his copy of The Times, places it beside him on the sofa, and tells her, “You’ve been a long way away,” adding, unbearably, “Thank you for coming back to me.”

What gives Brief Encounter its power is not what is said but what is not said: Fred’s declaration—unspoken, but no less unsentimental for that—that he is giving up the evil of crosswords. That his very English repression prevents him from saying this outright makes the denouement all the more moving.

(Better, always, to let the one you love take part in the filling of the grid . . .)