FALL IN A GARDEN, DEPICTED?

GENESIS

How the crossword first appeared in 1913 and became an overnight sensation in 1924

Newsday’s crossword editor puts it best. “Liverpool’s two greatest gifts to the world of popular culture,” writes Stanley Newman, “are the Beatles and Arthur Wynne.”

The comparison with the Beatles is on the money—or, to use a more British locution, spot-on. Like the music of the Fab Four, the crossword is a global phenomenon that is at once American and British. But while the Beatles are known wherever recorded music is played, Arthur Wynne’s name remains unspoken by almost all. Who was he?

Well, he wasn’t the Lennon or the McCartney of crosswords; we’ll meet them soon enough. He was perhaps crosswords’ Fats Domino: a pioneer who would see his innovation taken by others to strange, often baroque mutant forms and variants.

Not that this was how Wynne saw his career playing out when he became one of the forty million people who emigrated from Europe between 1830 and 1930, and one of the nine million heading from Liverpool for the New World during that same period.

The son of the editor of The Liverpool Mercury, Wynne was—at least initially, and in his own mind—a journalist. He spent most of his newspaper career working for the empire of print mogul William Randolph Hearst. His legacy, though, was not a piece of reporting, and it appeared in the New York World, a Democrat-supporting daily published by Hearst’s rival, Joseph Pulitzer.

As a kind of precursor to the New York Post, The World mixed sensation with investigation, and it was Wynne’s job to add puzzles to the jokes and cartoons for “Fun,” the Sunday magazine section. He had messed around with tried-and-tested formats: word searches, mazes, anagrams, rebuses.

Another available template was something called the word square, which we will look at in more detail in a later chapter. It takes up space, a very desirable property if you’re in charge of “Fun.” It asks the reader to think of answers. But it’s very limited. Imagine a crossword in which each answer appears twice in the grid: once as an across and again as a down. Very pleasing in terms of visual symmetry—whether foursquare square or tilted, as word squares often were, to make a diamond—but there are only so many words that fit with one another in this way.

It’s also a less demanding challenge for the solver: In a four-by-four word square, say, as soon as the first four-letter word goes in, once across and once down, the grid is 44 percent filled.

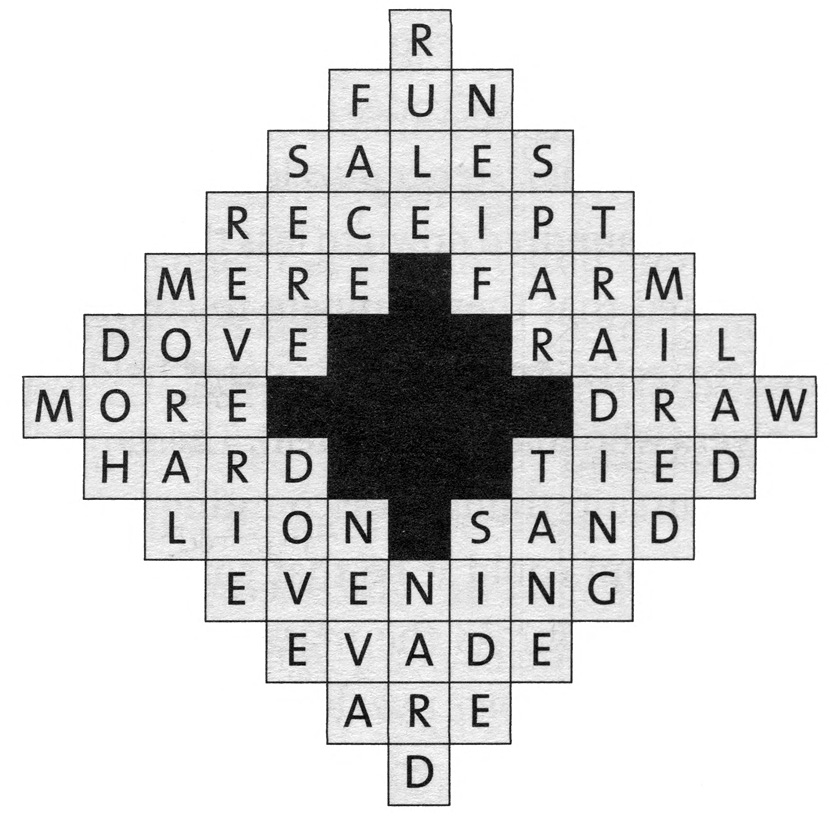

For the Christmas edition of the New York World on Sunday, December 21, 1913, Wynne tried something new. What if the entries read differently across and down? And so, without fanfare, this:

Fill in the small squares with words which agree with the following definitions.

|

2-3. |

What bargain hunters enjoy. |

|

6-22. |

What we all should be. |

|

4-5. |

A written acknowledgment. |

|

4-26. |

A day dream. |

|

6-7. |

Such and nothing more. |

|

2-11. |

A talon. |

|

10-11. |

A bird. |

|

19-28. |

A pigeon. |

|

14-15. |

Opposed to less. |

|

F-7. |

Part of your head. |

|

18-19. |

What this puzzle is. |

|

23-30. |

A river in Russia. |

|

22-23. |

An animal of prey. |

|

1-32. |

To govern. |

|

26-27. |

The close of a day. |

|

33-34. |

An aromatic plant. |

|

28-29. |

To elude. |

|

N-8. |

A fist. |

|

30-31. |

The plural of is. |

|

24-31. |

To agree with. |

|

8-9. |

To cultivate. |

|

3-12. |

Part of a ship. |

|

12-13. |

A bar of wood or iron. |

|

20-29. |

One. |

|

16-17. |

What artists learn to do. |

|

5-27. |

Exchanging. |

|

20-21. |

Fastened. |

|

9-25. |

To sink in mud. |

|

24-25. |

Found on the seashore. |

|

13-21. |

A boy. |

|

10-18. |

The fiber of the gomuti palm. |

The answers are in the Resources section at the end of this book. Puzzles nowadays don’t come with an instruction to “fill in the small squares” and would be more likely to clue DOH with a reference to Homer Simpson than by “Fiber of the gomuti palm,” but it’s recognizably a crossword. Or, rather, a “Word-Cross.” Wynne’s name is just as good a way of describing the pastime as the more familiar version, but a typographical anomaly two weeks later offered the alternative “Find the Missing Cross Words.” The following week’s heading announced a “Cross-Word Puzzle,” and that’s the version that stuck. It was to be some decades later that the name decisively shed its fussy capitals and sporadic hyphen.

It includes one answer twice (DOVE), and the clue for MIRED is—what’s a polite word here?—misleading, but there it is: a new thing in the world. The most important thing about the first puzzle is that big “FUN” across the second row. It might have been there because it was the name of the Sunday supplement, but it also served as a manifesto for crosswording. Individual puzzles may or may not be edifying, challenging, or distracting, but they must always be fun. After all, nobody is forcing solvers to look at them.

The second most important thing is the squares. The crossword’s antecedent, the double acrostic (again, see below), tended to offer only the clues: The solver put the answers together in his or her head, or found somewhere to write the letters. But twentieth-century printing technology made it easier to offer a grid depiction of the problem that was both clearer and more enticing, the little boxes staring up from the newsprint, begging to be filled.

The prewar period was one of linguistic innovation and reinvention. We will look at spoonerisms below. This was also a world that saw innovations with language: entirely new creations, such as the artificial languages Esperanto and Ido, and different means of conveying words, such as developments in stenography. And then there was the crossword, which broke up language into abstract units for reassembly: Rising newspaper sales and the age of mechanical reproduction helped to make the puzzle the most widely disseminated way of messing around with words. Even with the reader-compiled puzzles that occasionally took the place of Wynne’s in The World, though, it remained only a weekly phenomenon, and for the first ten years of its life it existed exclusively as an American phenomenon—indeed, it existed solely within the pages of that one newspaper. The puzzle had its devotees, but nobody spotted its potential until the faddish twenties arrived.

It became known to millions more in that decade when it started appearing outside The World—and not in other papers but in books. On January 2, 1924, the aspiring publisher Dick Simon went for supper with his aunt Wixie, who asked him where she could get a book of Cross-Words for a niece who had become addicted to the puzzles in The World. Simon mentioned the query to his would-be business partner, Lincoln Schuster, and they discovered that no such book existed.

On the one hand, this was good news: They had formed a publishing company but so far had no manuscripts to publish. On the other, their aspirations for Simon & Schuster were considerably higher than a collection of trivia(l) puzzles. The compromise was a corporate alias named after their telephone exchange: Plaza Publishing.

The next difficulty was getting the puzzles. As a first step Simon and Schuster approached not Wynne but one of his subordinates. Margaret Petherbridge had been appointed as a subeditor by The World in 1920; being both young and a woman, she was assigned the suitably lowly task of fact-checking the crosswords to try to reduce the volume of letters of complaint (of which more later), and now found her intended career in journalism permanently on hold.

Petherbridge was offered an advance of $25 to assemble enough puzzles for a book. Simon and Schuster decided to attach a sharpened pencil to every copy, priced it at $1.35, and spent their remaining prelaunch money on a one-inch ad in the New York World. Their campaign pushed the idea that the crossword was the Next Big Thing:

1921—Coué

1922—Mah Jong

1923—Bananas

1924—THE CROSS WORD PUZZLE BOOK

Long-shot business ventures rarely end well—the typical results are penury and shame. But the stories of failure are not often told, and this is not one of them. This is one of those familiar but wholly anomalous stories of unlikely triumph—where a bookseller friend of Simon buys twenty-five copies as a gesture of friendship but has to order thousands more; where The World’s top columnist, Franklin P. Adams, had predicted that Simon and Schuster would “lose their shirts,” only to start a piece four months later with the announcement: “Hooray! Hooray! Hooray! Hooray! The Cross-Word Puzzle Book is out today.”

It is also a story where:

• each of the four collections published that year topped the nonfiction bestseller list

• the second edition, priced at a more modest 25¢, received from the keenest of the distributors an order for 250,000 copies—then unprecedented in book publishing

• Simon & Schuster’s crossword compilations became the longest continuously published book series

It was the making of one of the major world publishers, and as rival firms produced their own puzzle series, it was excellent news for publishing in general—especially as, unlike pesky authors producing books of fiction or non-, crossword constructors would work for little or even no pay. The only downside for publishers was a side effect of the fierce competition: In case of low sales, Simon & Schuster offered to take back unsold crossword collections from bookshops, thereby instigating the practice of “returns,” very beneficial to megachains but increasing the element of risk for publishers ever since.

It was also the making of the crossword. The most intense interest in crosswords ever was in midtwenties America, and was largely centered on books of puzzles. It was only later that the newspaper reclaimed its status as the default home of the crossword. However, perhaps even more important than the number of solvers solving was the way the form matured. In 1926 Margaret Petherbridge had taken the name Farrar following her marriage to John C. Farrar, founder of another publishing giant, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. As Margaret Farrar, she tidied up the messy conventions of crosswording: She may have become involved with puzzling by chance, but she thought deeply and effectively about what made one crossword better than another.

Modern-day solvers (or “solutionists,” as they were sometimes described in the twenties) baffled by Wynne’s system for numbering clues have Farrar to thank for the cleaner “1 across” format, saving them, across a lifetime of solving, hours lost to tracing and connecting “F,” say, to “7.” Her preference for answers of at least three letters makes for a more satisfying experience, and the aesthetics she proposed for the grid are now characteristic of all puzzles (with the exception of some of the more willfully experimental examples we will meet along the way in this book).

Margaret Farrar’s parameters for an aesthetically pleasing grid are symmetry, a minimum letter-count of three in answers, and “all-over interlock”—in layman’s speak, the grid does not have separate sections and the solver can travel from any part of it to another.

Farrar’s ingenuity was finally rewarded in 1942 when she became The New York Times’s first crossword editor. Wynne had quietly retired in 1918 and died in Clearwater, Florida, in 1945. When the first crosswords appeared, he had wished to patent the format. Lacking the necessary funds for the process, however, he asked The World to contribute and was told by business manager F. D. White and assistant manager F. D. Carruthers that “it was just one of those puzzle fads that people would get tired of within six months.” In 1925, he did, however, obtain a patent for “an improvement or variation of the well-known cross word puzzle” in which the cells formed a kind of rhombus. Sadly, for him, it never took off.

Yet we crossword lovers should be very glad that Wynne failed to “own” the crossword. Even if such a claim were enforceable, given the puzzle’s obvious debt to earlier diversions, it is precisely the freedom of the format and the deviations from its original structure that have made crosswords such a rich format and such a satisfying pastime. Had the crossword been patented, it would indeed have been quickly forgotten and filed under “obsolete wordplay,” between the clerihew and the cryptarithm.

(The clerihew, by the by, was a form of comic verse that contained the name of a well-known person. And the cryptarithm, also known as the alphametic, was a mathematical puzzle in which an arithmetical proposition has its numbers replaced by letters. Neither, so far as I know, ever achieved sufficient popularity to be rendered in the form of cookies, earrings, or novelty songs. Unlike . . .)