Rookie sensation Gene Conley contributed to a Braves pitching staff that finished second in the league in 1954 with a team ERA of 3.19. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The Braves began their 1954 spring training with visions of not just challenging Brooklyn for the National League crown but besting them for it outright. Cutting ties with several of the Boston-era holdovers during the off-season, Milwaukee general manager John Quinn sent veterans Sid Gordon and Max Surkont to Pittsburgh for flashy fielding second baseman Danny O’Connell. With Gordon’s departure, the Braves lacked a starting left fielder and lineup protection for sluggers Eddie Mathews and Joe Adcock. But in one swift stroke, Quinn acquired a slugger to solve both problems.

Bobby Thomson needed no introduction when he arrived at the Braves’ Bradenton, Florida, spring training facility. “The Flying Scot” was already famous for clobbering the ninth-inning “shot heard ’round the world” to clinch the 1951 National League pennant for the Giants over the rival Dodgers. Acquired by the Braves in a six-player deal that sent pitcher Johnny Antonelli to the Giants, Thomson boasted three consecutive one hundred–plus RBI seasons, the perfect complement to sluggers Mathews and Adcock.

Another promising prospect arrived at Braves camp without any fanfare but made quite an unexpected impression on manager Charlie Grimm. “The first day of spring training in 1954, I was parked in front of my locker when [equipment manager] Joe Taylor yelled that a young fellow outside wanted to see me,” Grimm recounted in his autobiography Jolly Cholly’s Story. Thinking he had been summoned to greet just another youngster looking for a tryout, Grimm took his time getting up. Standing with Taylor at the front of the clubhouse stood a twenty-year-old named Henry Aaron. “At six feet and 180 pounds he looked slim but was all muscle,” the Braves skipper remembered.

Braves manager Charlie Grimm (wearing windbreaker, on far left) often conducted relaxed spring training workouts. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The Braves veterans didn’t seem to know or care about Aaron’s illustrious minor-league career, which included two MVP honors. “I didn’t remember Aaron at first,” third baseman Eddie Mathews said, “and there was no reason I should have. Regulars don’t pay much attention to rookies, and he wasn’t even on our roster.”

With everyone’s attention on Thomson and the potential of the Braves newly stacked lineup of sluggers, Aaron spent most of his time quietly keeping to himself. “The first few days of spring training, hardly anybody knew I was around,” Aaron reflected twenty years later. “I also remember the name over my locker being spelled ‘Arron.’ And so I don’t remember feeling like a phenom in the spring of 1954.”

During an exhibition game against the Yankees, Bobby Thomson suffered a severely broken ankle while sliding under second baseman Woodie Held. The freak accident sidelined the Braves’ newest left fielder indefinitely. “That injury took a lot of starch out of us,” Charlie Grimm remembered.

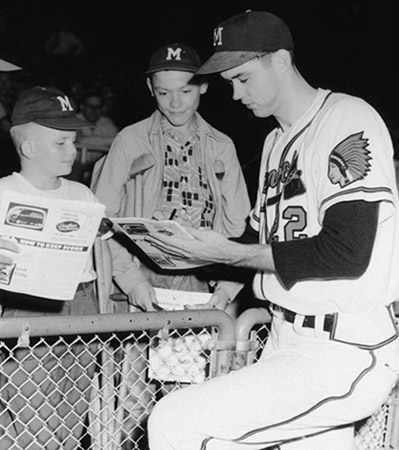

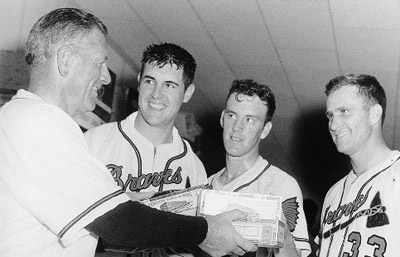

Bobby Thomson (34) and Bob Buhl (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

When Thomson was carried off the field on a stretcher, the Braves were forced to turn to rookie Henry Aaron. “I didn’t realize it then. Heck, I wasn’t mature enough to realize anything but sunup, sundown and mealtime,” Aaron remembered. “Anyway, that was my ticket to the big leagues going by me on the way to the hospital.”

The following day Grimm put Aaron in left field during an exhibition game against the Boston Red Sox. The rookie responded with three hits, including a single and a triple. But it was his low line drive that rocketed over a row of trailers beyond the outfield fence that grabbed the attention of a future Hall of Famer. “Ted [Williams] tells the story about how he heard, but did not see, Aaron’s first home run in a Braves uniform,” Braves publicity director Donald Davidson recounted in his autobiography Caught Short. “Ted was out of the lineup and heading for the clubhouse when he heard a bat crack like a rifle. He trotted back to the dugout and asked who hit that ball. They told him some kid named Aaron, and Ted advised everyone to remember his name.”

During spring training in Bradenton, Henry Aaron, Charlie White, Billy Bruton, and the other black Braves players lived in an apartment over a garage owned by schoolteacher Lulu Gibson. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

It wasn’t long afterward that Grimm threw a glove to Aaron and proclaimed, “Kid, you’re my left fielder. It’s yours until somebody takes it away from you.” Letting his bat do the talking during the rest of spring training, the soft-spoken Aaron went from unnoticed, non-roster spring training invitee to the Braves’ Opening Day starting left fielder.

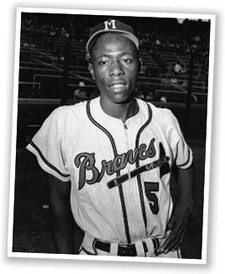

Before arriving at the Braves’ 1954 spring training camp, Henry Aaron won MVP honors during his first two years of minor-league baseball in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, and Jacksonville, Florida. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Going into the season opener, the Braves were the sentimental pick to win the National League flag in 1954. But Charlie Grimm was quick to quell expectations. “Brooklyn, of course, is the team to beat. We’ll be up there around the top. So will the Cardinals and the Phillies. It will be rough for the second division teams of last year to move up. But this is a league where you can stub your toe often,” Grimm insisted in the 1954 Street and Smith Baseball Yearbook.

For the Braves’ Opening Day contest at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, an eager crowd of 33,185—including a large contingent of boosters from Milwaukee—required overflow seating. “When you were batting, it was hard to pick up on the pitch because of the crowd in the roped-off area in the outfield,” Andy Pafko remembered. “Because of the overflow crowd, there were twelve ground-rule doubles in the game.” Losing the two-bagger fest to the Redlegs 9–8, the Braves looked to rebound during their home opener against the Cardinals.

Two days later, an exuberant crowd of 39,963 packed into County Stadium as Warren Spahn hurled an eleven-inning, complete-game victory against St. Louis. It was one of the Braves’ few bright spots in April as they sank into the National League cellar with a 5–8 record by the end of the month. The Braves’ cold start prompted Grimm to move 6′8″ pitching prospect Gene Conley from the bullpen into the starting rotation. He explained in his memoir, “The skyscraping right-hander had won 23 games for Toledo, and we were confident he’d win big for us.”

With an athletic résumé that included being a three-letter athlete in baseball, basketball, and track in Richland, Washington, and an All-American at Washington State University, Conley was as well known for throwing a mean fastball as he was for swishing a fifteen-foot jump shot. Fresh off his second Sporting News Minor League Player of the Year award when he joined the starting rotation alongside Warren Spahn, Lou Burdette, Bob Buhl, and Chet Nichols, Conley immediately began helping the Braves pull out close games, resulting in a ten-game winning streak. By the end of May, Milwaukee led the league, a game and a half ahead of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

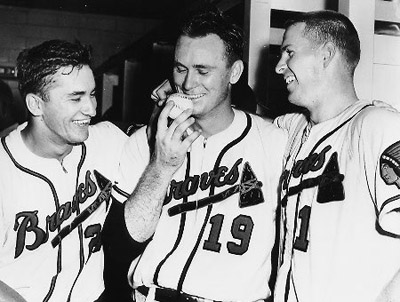

But the Braves proceeded to lose ten of their next twelve contests in what would be a season-long series of highs and lows. Mired in fourth place, the Braves benefited from one of their most unlikely heroes, pitcher Jim Wilson. Ever since a line drive off the bat of Detroit’s Hank Greenberg struck him in the head in 1945, Wilson had battled his way back into the majors. When the Braves were short on starting pitchers during a doubleheader against Pittsburgh on June 6, Wilson jumped at the opportunity and shut out the Pirates 5–0. Following Wilson’s surprising performance, Grimm started him on June 12 against the Philadelphia Phillies. The thirty-two-year-old journeyman pitcher responded by hurling the first no-hitter at County Stadium, winning the game for the Braves 2–0.

By the All-Star break on July 14, the Braves found themselves fifteen games behind the Giants, with a mediocre 41–41 record. Once again the Braves were well represented in the Midsummer Classic as Warren Spahn, Gene Conley, Del Crandall, and Jim Wilson, who earned an invite based on his personal eight-game winning streak, rounded out the roster. With the hometown Cleveland crowd in a frenzy after the Indians’ Larry Doby connected for a pinch-hit, game-tying home run, the bases were loaded when Conley took the mound in the eighth inning. The Braves’ rookie sensation looked to shut down the American League, but the White Sox’s Nellie Fox knocked a Conley pitch into short center field, bringing in the winning runs. The American League’s 11–9 victory tagged Conley with the loss during a disastrous third of an inning. Stepping off the mound with tears streaming down his face, Conley offered no excuses. “I goofed up out there,” he told reporters in the locker room after the game. “I was terrible.”

Pitcher Jim Wilson (center) celebrated Milwaukee County Stadium’s first no-hitter with shortstop Johnny Logan (left) and catcher Del Crandall (right). (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

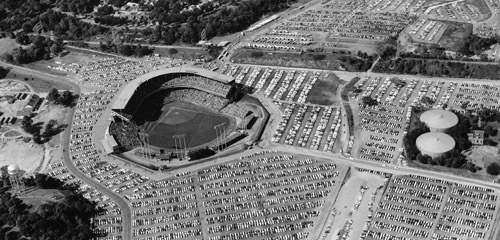

Following the All-Star Game, Milwaukee became the first club that season to hit the one million mark in attendance—proving once again that County Stadium was the city’s social center. “In my rookie year, the Braves’ initial print order for tickets was the largest ticket order in the history of the printing business,” Aaron recalled in his autobiography I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story.

By 1954 the Braves were considered progressive in their efforts to integrate their roster with black players, including Jim Pendleton, Charlie White, Billy Bruton, and Henry Aaron. But in a July 17 game against Brooklyn, the Braves witnessed history as the Dodgers’ starting lineup featured Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Junior Gilliam, Sandy Amoros, and Don Newcombe—the first time in major-league history that a lineup had more black players than white. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

With more than nine thousand season tickets ordered prior to the start of the 1954 season, the Braves continued building on their attendance success by making the stadium a family-friendly place to spend summer afternoons and evenings. Much like going to the theater, County Stadium fans treated each game as an event worth looking their best for. “Almost every one of the men wore a jacket and tie—some of them wore an overcoat and hat as well—and just about all of the women, my mother included, wore a dress and hat,” future Braves catcher Joe Torre said in his autobiography, Chasing the Dream.

The Braves estimated 37 percent of season tickets were in the hands of women, with daily attendance even higher. To increase the game’s popularity among women, the Milwaukee Sentinel and Warren Spahn’s wife, LoRene Spahn, hosted clinics for packed auditoriums of intrigued women. To attract the younger generation, the team introduced the major leagues’ first Girls’ Knot Hole Club in June 1954. The promotion not only encouraged girls to spend their allowances at the concession stands but also introduced them to the game so they’d return as paying customers when they grew up. Businesses around Milwaukee catered to female fans. Hairdressers introduced a Braves hairdo. Florists arranged “Braves carnations.” And bartenders mixed Braves cocktails. Several of the players’ wives participated in radio and television commercials, and an upscale clothing store hired them to model the latest fashions, placing their photographs in full-page ads in the Milwaukee Journal.

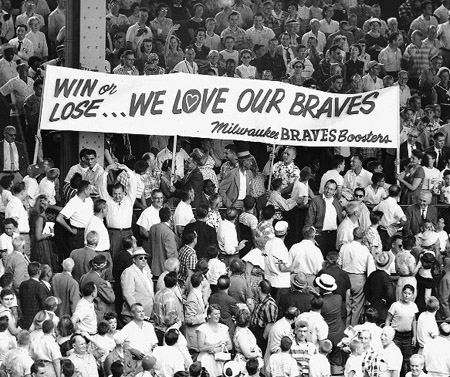

Braves mania was sweeping Wisconsin, and the Milwaukee Braves Booster Club had the numbers to prove it. It became the largest booster club in baseball during the 1954 season with more than twenty-three thousand members in more than 450 Wisconsin towns and cities, along with another 525 communities in other states receiving the club’s publication, The Tomahawk. The boosters organized trips to Bradenton for spring training and to regular-season destinations such as Brooklyn, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago to support the Braves. Their successful season of cheering was capped off with a special seventeen-car train that carried 442 members to St. Louis for Milwaukee’s final road series.

For fans unable to attend Braves games in person, radio was the only option in the Upper Midwest. While other baseball owners committed to television contracts, Lou Perini refused to permit any telecasting of Braves games—home or road—in Milwaukee territory. The fans’ insatiable appetite for baseball led to a well-organized 1954 campaign that produced more than fifty thousand petition signatures asking the Braves to televise road games. But Perini didn’t budge, claiming that even if the TV fees fully offset the gate losses, broadcasting games still wasn’t an option: “Because a team performs better before a greater number of spectators, the Braves management does not feel it is in their best interest, in the best interests of baseball or in the best interest of Milwaukee and the state of Wisconsin to televise our out-of-town games.”

The Braves regrouped after the All-Star break and won forty-two of their next fifty-four games. “We rallied in July. The one game that stands out was on the last day of the month, when Adcock came up with the greatest slugging performance in history,” Charlie Grimm said. Borrowing the bat of teammate Charlie White after having shattered his own the night before, Joe Adcock continued to hit Brooklyn’s pitching well, improving his already impressive .442 batting average against them that season. On July 31 Adcock led off the top of the second inning with a home run to left field. After he doubled and later scored in the fourth, the Braves took a commanding 6–1 lead. In the fifth, Adcock smashed a three-run homer into the upper deck, putting the Braves up 9–1. With a two-run homer in the seventh inning and his fourth home run of the day in the ninth, Adcock and the Braves went on to a dominating 15–7 win. In just one game, Adcock accumulated seven RBIs, scored five runs, and established a major-league record of eighteen total bases with four home runs and a double. “It was one of those things you just can’t explain,” Adcock told Sport magazine. “Every time I swung the bat, I must have hit the ball on the nose.”

Charged with building interest among potential fans was the Braves’ goodwill ambassador, Hal Goodnough. During his first two and a half years on the job, the former schoolmaster drove more than sixty-three thousand miles and made more than 650 speeches to groups across Wisconsin, from kindergarten classes, bankers’ groups, churches, and nursing homes to state prisons. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Braves boosters were some of the most enthusiastic and dedicated in all of baseball. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The Braves introduced the major leagues’ first Girls’ Knot Hole Club during the 1954 season. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The Milwaukee Braves organization was groundbreaking in its marketing of baseball to women. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

The day after Adcock’s record-breaking performance, the Braves routed the Dodgers again. To silence the Braves’ offensive juggernaut, Brooklyn’s Clem Labine bounced a fastball off Adcock’s head in the fourth inning. “There was no fight, but Adcock would have been seriously injured if he had not been wearing his batting helmet,” Donald Davidson recalled in Caught Short. “Joe’s protective headgear was split in two by Labine’s pitch.” Adcock was carried from the field, his bat finally silenced. In the bottom of the sixth, the Braves’ Gene Conley reciprocated by knocking down Jackie Robinson, who in turn ended up scrapping with Eddie Mathews. In the end, the Braves clinched their tenth win in a row with a 10–5 victory—Conley’s ninth straight win.

On July 31, 1954, Joe Adcock saw just seven pitches in his five at bats while clobbering four home runs against the Dodgers. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Having won twenty of twenty-two, the Braves were within a mere three and a half games of the top by August 15. “Despite some ups and downs, the Braves fully expected to be playing in the World Series that season,” Eddie Mathews noted in his autobiography, Eddie Mathews and the National Pastime.

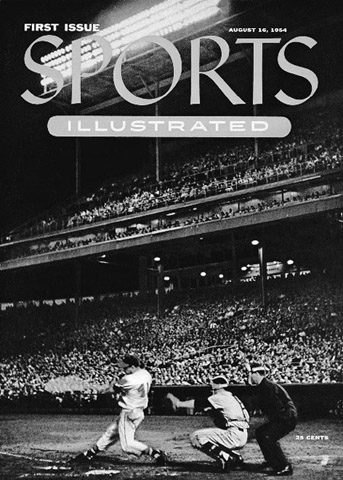

As the Braves continued to rise in the standings, Mathews and the “Milwaukee Miracle” were featured on the inaugural cover of Sports Illustrated on August 16, 1954. “The photographer said he took about 150 shots of different players and turned them all over to the editor,” Mathews recalled. “The editor chose that particular photograph because he said it was timeless—you don’t really see anybody’s face, and it doesn’t emphasize an individual, but rather a scene that’s repeated thousands and thousands of times every year.”

It was a natural choice for the upstart magazine, since at the time most considered Mathews to be the greatest threat to break Babe Ruth’s all-time home-run record. “If anybody can do it I’d say Eddie has the chance,” Grimm told reporters. “He has a fine disposition, he does nothing to impair his great physical condition and I believe he has remained unspoiled by all the hero worship that has come his way in Milwaukee.”

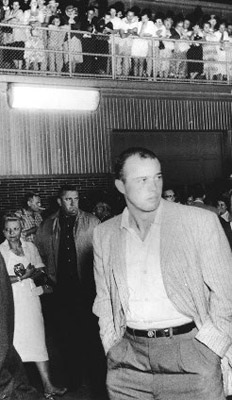

Admired as much for his All-American looks as his athletic ability, Mathews never sought out the spotlight, even as a stellar high school running back in Santa Barbara, California. Although he was approached by several colleges offering football scholarships, Mathews signed with the Braves after they offered him a $6,000 guaranteed contract. Mathews felt the guaranteed money would immediately benefit his family. When he reached Milwaukee, he continued to reluctantly avoid the spotlight. His reputation as a tough interview quickly spread. “What can a guy like me tell them that would be worth printing?” Mathews asked. “I’ll try to answer their questions, but they’ve got to realize that baseball comes first with me. I’m not the most pleasant guy to be around after I’ve gone 0-for-4.”

Braves third baseman Eddie Mathews graced the inaugural Sports Illustrated cover on August 16, 1954. (SPORTS ILLUSTRATED)

Eddie Mathews grew increasingly disenchanted with the attention he received as a superstar in Milwaukee. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

But as a shy and otherwise introverted athlete, Mathews grew increasingly uncomfortable with the prediction that he would be heir to Ruth’s crown. “What everybody seems to forget,” Quinn scolded reporters, “is that when they’re dealing with Mathews, they’re dealing with a boy. Here he is 23 years old and he’s already been in the major leagues three seasons.”

At first Mathews regarded the flood of attention with affectionate amusement, but eventually it began to wear on him. Wherever he went in Milwaukee, admirers hovered. He couldn’t eat, watch a movie, or walk around a street corner without being ambushed with an autograph request. “Why, I’ve known him to stay in the clubhouse for two hours after a game trying to escape the crowd of fans,” Braves coach Bucky Walters told the Street & Smith Baseball Yearbook in 1954. “But they’re always waiting for him, especially the girls. Gosh, how those gals go for him!”

Mathews lost his fun-loving attitude, even toward the same writers and fans who had helped coronate him as the king of Milwaukee. He began avoiding the public and found solace in nightclubs and alcohol. “Mathews liked to have a good time and was probably the hardest-living guy on the team,” Henry Aaron wrote in his autobiography I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story. “I didn’t go out with Mathews very often because you never knew what might happen.” That summer, Mathews’s off-the-field exploits jumped from the sports section onto the front pages of the Milwaukee newspapers. A story chronicled Mathews’s arrest in the early morning hours for speeding, running a traffic light, and giving a Wauwatosa traffic cop a hard time. Although the charge was presented in court as nothing more than a speeding violation, Mathews’s reputation had been tarnished. Fined fifty dollars by the court and another one hundred dollars by manager Charlie Grimm, the Braves slugger realized the effect on his checkbook was minimal compared to the shower of disappointment from reporters and fans. While the incident was one of the most important steps in Mathews’s process of growing up, it also hardened his resolve to keep his private life out of the spotlight.

Despite his lack of interest in speaking with reporters, Mathews won over many of the Braves veterans with his dedication on the diamond. “Eddie came to play every day. He never missed a ballgame,” Warren Spahn asserted. “I was with the Braves when Eddie came up in ’52, and he couldn’t stop a ground ball. He worked every day until he became a good fielder.”

Following his appearance on the cover of Sports Illustrated, Mathews had the dubious distinction of being the first victim of the “Sports Illustrated jinx”—a long succession of athletes have inexplicably been injured, lost the big game, or endured lackluster performances after appearing on the magazine’s cover. During a game against the Cubs on August 22, Mathews was hit on the hand by pitcher Hal Jeffcoat. The injury required stitches and kept him out of the lineup for nearly two weeks. “The ball jammed my middle finger against the bat and split the finger wide open,” Mathews remembered. “It bled like a stuck pig.”

On August 29 the Dodgers swept the Braves in a doubleheader. But County Stadium’s crowd of 45,922 fans brought the season’s total to 1,841,666, a new National League record. “At the end of August we had already hustled more customers into the stadium than during the entire first season,” Charlie Grimm noted. Building on the tremendous statewide interest, the Braves created eleven ticket agencies in Wisconsin cities within a hundred-mile radius of Milwaukee that had populations in excess of twenty-five thousand. “The Braves had made it easier for the outlying fans to buy the precious tickets, setting up branch offices in Fond du Lac, Oshkosh, Appleton, Racine, Kenosha, Madison, Beloit, Janesville, Sheboygan, Manitowoc and Green Bay,” Grimm recounted in Jolly Cholly’s Story. County Stadium’s encore performance at the ticket turnstiles proved that Milwaukee’s honeymoon with the team wasn’t a one-year affair. When the final figures were tabulated at the end of the 1954 season, a grand total of 2,131,388 fans had witnessed the “Milwaukee Miracle.”

Nobody relished Milwaukee’s success more than the Braves’ forty-eight-inch-tall publicity director, Donald Davidson. Davidson had grown up around the game, serving as a mascot, batboy, and press box attendant in Boston. After moving up to the Braves’ front office in 1948, Davidson spent most of his career as the team’s publicity director and later as its traveling secretary. “Donald was tough. He really demanded respect and he got it,” Mathews recalled. While his size got him noticed in a crowd, it was his personality that made him one of baseball’s most colorful front-office personalities. “He would swear a blue streak at us. God, he could cuss. Even for baseball, his language was exceptional,” Mathews said.

Since County Stadium was often sold out, the Braves encouraged patients at the National Soldiers Home Veterans Administration Hospital to watch games from sloping Mockingbird Hill, which overlooked right field. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

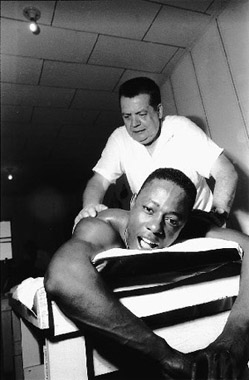

Braves pitcher Gene Conley and publicity director Donald Davidson (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

As publicity director in 1954, Davidson decided that “Hank” sounded more “personable” than Henry when referring to the team’s shy rookie tearing up National League pitching. Davidson was also responsible for assigning Aaron one of the most recognizable numbers in baseball history. According to Aaron’s biography Aaron, he was originally assigned the number 5 upon signing up with the Braves. When he requested a double-digit jersey, Davidson replied to the request with a sarcastic, “Like what? You’re so skinny, I don’t know how a little bastard like you could carry two numbers around.”

“I don’t mean just any kind of double number. I mean like 22, 33, or 44, something like that,” Aaron replied.

Davidson retorted, “Henry, dammit, don’t you know that all the great ones were single numbers? Babe Ruth was number 3, Lou Gehrig was number [4]. Joe DiMaggio was number 9. Stan Musial is number 6. Ted Williams is number 9. Mickey Mantle is number 7. And you want to carry two numbers around?”

But by Labor Day weekend, Aaron’s jersey request was temporarily forgotten while Milwaukee focused on overtaking the first-place Giants. The Braves arrived in Cincinnati still capable of clinching the pennant. “Our dugout was alive and you had that feeling that something great was about to happen to this ball club,” Aaron recalled. “We were still in the pennant race. We were just five games back of the Giants, who were leading and right on the Dodgers’ tails.”

The Braves won the first game of the September 5 doubleheader 11–8. Aaron led the charge in the second game. After he smacked a screaming line drive into center field, the Braves rookie looked to make his fifth hit of the day a triple. Rounding second base, he hit the dirt and broke his ankle sliding into third. “You’ll never guess who came in to run for me—Bobby Thomson himself. Bobby begins the season in the hospital and I take his job and I end the season in the hospital and he gets his job back,” Aaron said. “By this time, though, I knew something I didn’t know when Bobby went to the hospital. I knew I could play in the big leagues.”

Despite sitting out nearly the entire last month of the 1954 season in an ankle cast, Henry Aaron still played in 122 games, collected 131 hits, belted 13 home runs, and drove home 69 runs with a solid .280 batting average. (WHI IMAGE ID 26384)

The Braves went on to sweep the Redlegs, dominate the Cubs, and pound the Pirates to secure their third ten-game winning streak of the season. With just four games separating them from the National League–leading New York Giants on September 10, the Braves traveled to Brooklyn for another heated late-season series. “Whenever we played the Dodgers, somebody got knocked down or beaned or words were exchanged,” Mathews remembered.

Although Milwaukee lost the opener, Joe Adcock connected for his ninth round-tripper in Ebbets Field that season—tying the major-league mark for the most homers in an opposing park in one year. During twenty-two games against the Dodgers in 1954, Adcock had batted .395, with thirty-two hits, nine homers, and twenty-two RBIs. Tired of being terrorized, the Dodgers’ pitching staff was desperate to silence the Braves’ bats. “See, in those days, we had knockdowns. If a batter was having a lot of success against a pitcher or against his team, the pitcher would knock him down. He wouldn’t necessarily hit you, but he would throw inside or near your head,” Eddie Mathews explained. “We pretty much accepted that fact.”

The Dodgers’ Don Newcombe snuffed out the remainder of the Braves’ season with one pitch by breaking Adcock’s wrist. With Aaron already lost for the season, the wheels came off the Braves offense, and they quietly faded into third place, eight games behind the champion Giants and three behind the Dodgers, with an 89–65 record.

Although the Braves had established themselves as legitimate pennant contenders, the first criticism of Charlie Grimm’s relaxed and fun-loving managerial style arose from the team’s disgruntled second baseman. “Danny [O’Connell] was an aggressive ball player who spoke his mind, but he was a long time blaming me for the Braves’ failure to win the 1954 pennant. He said a lack of fighting spirit cost us the flag,” Grimm remembered. “That’s O’Connell’s version. It’s his privilege if he wants to pop off. And it won’t make me change my system of managing. I think I’m aggressive in my own way. And I think our team was that way on the field.”

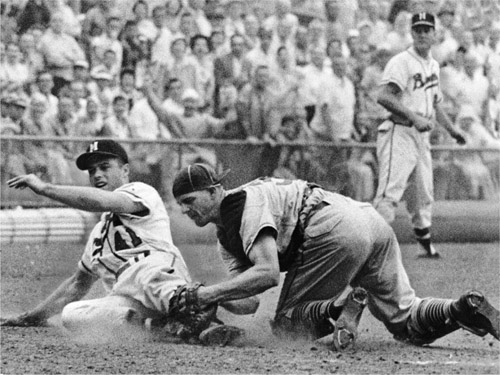

Jack Dittmer (tagging out Brooklyn’s Jackie Robinson at second base) was part of Milwaukee’s league-leading defensive unit in 1954. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Suffering from an injury-plagued roster all season combined with a slow start in April, Milwaukee still featured one of the top offenses, defenses, and pitching staffs in baseball during the 1954 season. “We didn’t win the pennant,” Aaron said. “But the Braves’ time was coming. We were all going to grow a little bit each season. A pennant wasn’t far off.”

♦ ♦ ♦

During the off-season, the franchise lost its number one booster when brewery mogul Frederick Miller’s airplane crashed and burned shortly after taking off from Milwaukee’s Billy Mitchell Airport. Miller, his twenty-year-old son Fred Jr., and two pilots employed by Miller Brewing Company had been on their way to a hunting cabin in Canada; all four were killed. With Miller’s untimely death, Wisconsin was without one of its most generous residents. “As a businessman Mr. Miller obviously recognized the advertising potential that sports held for his product, but his interest in sports went far beyond that,” Eddie Mathews recalled. “When the Green Bay Packers were threatened with bankruptcy in the early ’50s, he bought stock and sponsored radio broadcasts and helped sell tickets.”

Some observers thought that, as a personal and professional confidant of Lou Perini, Miller might have had a larger role in the Braves’ future. “Before his death there was a lot of conversation that Miller might buy out Perini. Who knows, had Miller lived, the Braves might still be in Milwaukee,” Charlie Grimm speculated in his 1968 memoir.

With heavy hearts, several Braves players reported to camp before the approved March 1 starting date, looking to build on their previous season’s third-place finish. “I still needed some hard work to get in shape after having the cast on all winter, so, at John Quinn’s request, I reported early to Bradenton,” Hank Aaron recalled. “After I was there a day or so, I got a telegram from the commissioner, Ford Frick, telling me I was fined for reporting early.”

Ford Frick’s five hundred dollar fine wasn’t the only thing Aaron found hanging in his locker. There was also a tomahawk-clad double-digit jersey with the number 44 on the back. Despite his ribbing of Aaron, Donald Davidson fondly recalled in his autobiography Caught Short that “four times in his career he hit 44 home runs, and I regret that I did not give him number 70.”

By the end of spring training, prognosticators felt the Braves had the earmarks of a scrappy pennant contender—youth blended with experience, a combination Grimm hoped to craft into a pennant winner. “In our plans for 1955, we were trying to fit in the pieces that would give the doting fans their just reward,” he explained.

Milwaukee County Stadium’s turnstiles clicked at a record pace for the 1955 home opener, as 43,640 enthusiastic fans broke a National League Opening Day attendance record. The electrified crowd in full Braves regalia bought baseball caps at $2, T-shirts for $1, team jackets at $6.95, and official uniforms for $7.95 at the novelty stands throughout the ballpark.

On the diamond, Milwaukee’s Warren Spahn dueled against Cincinnati’s Gerry Staley. With the Braves trailing 2–1 in the bottom of the eighth inning, rookie Chuck Tanner went in to pinch hit for Spahn. Making his major-league debut, Tanner refused to waste any swings at the plate and proceeded to blast Staley’s first pitch into the right-field bleachers. Tanner’s round-tripper tied the score at two and ignited the Braves. They tallied another pair of runs later in the inning to clinch the 4–2 win over the Redlegs for the dramatic Opening Day finish.

The Milwaukee Braves’ 1955 Opening Day lineup featured (from left to right) Billy Bruton, Danny O’Connell, Eddie Mathews, Andy Pafko, Henry Aaron, Joe Adcock, Johnny Logan, Del Crandall, and Bob Buhl (not pictured). (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The remainder of April found the Braves mired between fourth and fifth place due to their slow start and inconsistent play. Meanwhile, the Dodgers started their season with ten straight wins. By the middle of May, after winning twenty-two of their first twenty-four contests, the Dodgers were so far ahead in the standings that only a complete implosion on their part would jeopardize their firm early-season grasp of the 1955 National League pennant.

Henry Aaron and Warren Spahn congratulated Chuck Tanner (right) after he became the first player to hit a pinch-hit home run on the first pitch he saw during his first major-league at bat. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Behind the relentless efforts of Eddie Mathews, the Braves looked to fight their way back into the race. With his magnificently coordinated swing, lightning reflexes, and powerful wrists, Mathews grabbed the attention of one Hall of Famer often reluctant to compliment contemporary ballplayers. “I’ve seen three or four perfect swings in my time. This lad has one of them,” Ty Cobb told reporters.

But on May 17 Mathews grew increasingly ill during a game against the Giants—though he managed to collect two hits. After the game, Mathews went to see the team doctor. “He gave me a funny little test. He had me lie down on a table, and he pushed in on my stomach and let out real quick. Well, that damn near put me on the ceiling.”

The test instantly diagnosed the source of Mathews’s pain. “Two days later, Mathews awakened in his hospital room minus his appendix.” Davidson recollected. “His first question to the doctor was, ‘When will I be able to play ball again?’ ” Originally forecast to lose three weeks after the surgery, the consummate gamer accelerated his recovery and appeared in the clubhouse four days later, checking on his favorite weapons in the bat rack. Just two weeks after the surgery, Mathews was back in Braves’ flannels and standing in the batter’s box. On June 2, by connecting for a pinch-hit home run in Brooklyn, Mathews demonstrated that his recovery was complete, and the next day he was in the starting lineup at third base. “Nobody ever again questioned the guts and determination of Edwin Lee Mathews,” Donald Davidson bragged.

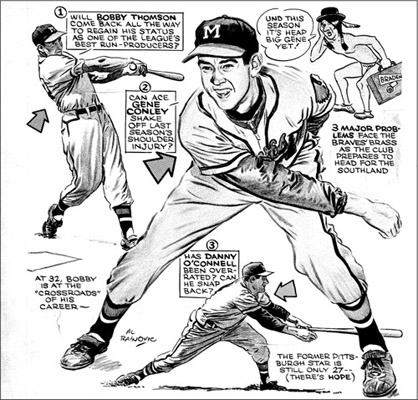

Milwaukee Journal cartoonist Al Rainovic illustrated the frustration Braves fans felt in 1955 as the Dodgers distanced themselves from the rest of the National League. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 268)

Eddie Mathews hit more than forty home runs for the third straight season in 1955 and led the league with 109 walks. (WHI IMAGE ID 6225)

By the end of June the Dodgers had distanced themselves further in the pennant race. Meanwhile, Milwaukee focused on hosting the biggest sporting event in the state’s history: the 1955 All-Star Game. Determined to showcase Milwaukee as a major-league-caliber city, civic officials organized cultural activities throughout the week leading up to the game. None was more popular than a parade and lakefront extravaganza, complete with ships, aircraft, and fireworks, that attracted an estimated 250,000 people. Nothing had to be done to fuel interest in the game, as baseball’s hottest ticket was sold out weeks in advance. That didn’t stop thousands of aspiring fans from milling around County Stadium before the July 12 game in hopes of acquiring a last-minute ticket.

Inside County Stadium, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley scanned the standing-room-only crowd of 45,314 rabid fans. Mystified, he asked Braves owner Lou Perini to explain how Milwaukee continued to be the hottest draw in baseball. “There’s no secret formula,” Perini told him. “It’s just the terrific enthusiasm. All the people have something in common with the team. The priest talks about the Braves to the rabbi; the mechanic to the industrialist; the housekeeper to the butcher.”

A sold-out Milwaukee County Stadium hosted some of Major League Baseball’s brightest stars and most influential dignitaries during the 1955 Midsummer Classic. (WHI IMAGE ID 50114)

Mickey Mantle was congratulated at home plate by Yogi Berra (8), Nellie Fox (2), and Ted Williams (9) after his first-inning three-run home run gave the American League an early 4–0 lead in the 1955 All-Star Game. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The Braves-biased crowd had reason to be excited, because Milwaukee was well represented on the National League squad. Del Crandall and Eddie Mathews were starters. Henry Aaron came off the bench in the fifth inning, and Johnny Logan drove in the National League’s first run in the seventh. In the eighth, still trailing 5–2 with two outs, the National League seemed destined to lose. But they rallied to tie the score as the game went into extra innings for only the second time in All-Star Game history. Milwaukee’s loyal fans nervously stayed in their seats, refusing to leave until a victor was decided. Entering the top of the twelfth inning with the score still tied at five, the Braves’ Gene Conley took the mound to face three of the American League’s most potent bats: Al Kaline of the Detroit Tigers, Mickey Vernon of the Washington Senators, and Al Rosen of the Cleveland Indians. His previous year’s All-Star Game failure still fresh in his memory, baseball’s tallest player proceeded to strike out the side in succession. “I was calm until the half inning was over,” Conley told reporters after the game. “Then, when the cheering started I got so nervous I couldn’t even see the crowd.”

With the game’s momentum coursing through the National League dugout, St. Louis Cardinal Stan Musial grabbed his bat, sensing an appointment with destiny. “I was sitting in the dugout—it was my second year—and I remember Stan pacing and saying, ‘Well, they don’t pay me for overtime,’ ” Aaron said. Musial stepped to the plate and pounced on American Leaguer Frank Sullivan’s first pitch, driving it into the right-field bleachers. It was one of the most dramatic finishes in All-Star Game history, as Musial’s homer secured Conley’s triumph for the National League’s come-from-behind 6–5 victory. “We gave a good account of ourselves,” Aaron admitted. “Gene, Logan, myself. We made Milwaukee proud.”

Following the All-Star Game, injuries continued to keep the Braves from gaining ground on the Dodgers. Soft-spoken relief specialist Dave Jolly was hampered by a sore arm that limited his availability. Gene Conley also suffered from an arm ailment and pitched only once during the season’s second half. Although Milwaukee benefited from calling up Ray Crone, who won ten games from June 17 to the season’s end, he couldn’t compensate for the Braves’ crippled everyday lineup. Bobby Thomson had fully recovered from his broken leg the previous year but had hurt his shoulder in May and was limited to just 101 games. And the team’s harshest injury of the season sidelined Joe Adcock on the first anniversary of his record-breaking day. During his first trip to the plate on July 31, Adcock was struck in the arm by the Giants’ Jim Hearn. The errant pitch broke Adcock’s right arm and exiled him to the disabled list for the remainder of the season. Although George Crowe filled in admirably at first base, Adcock’s absence compounded an already slumping Braves lineup.

Braves pitchers (left to right) Bob Buhl, Ray Crone, Lou Burdette, Chet Nichols, Warren Spahn, and Ernie Johnson (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Shortstop Johnny Logan was forced to abandon his 451-consecutive-games-played streak after a deep slump late in the season. Second baseman Danny O’Connell became a liability at the plate as his batting average nosedived from .294 in 1952 to an anemic .225 by 1955. With hopes of adding some much-needed punch into the Braves infield, Grimm relocated Aaron to second base for twenty-seven games. Even Milwaukee’s most devoted fans realized that all the Braves were fighting for in September was the opportunity to finish as the National League’s runner-up. “We had a ‘tenth’ player that year, a fellow named Bill Sherwood,” Grimm recalled in Jolly Cholly’s Story. “He shinnied up to the top of the flagpole on June 23 and vowed to remain until we’d won seven games in a row. But after sitting up there for 89 days, and after we’d stopped three times after winning six straight, he finally gave up.”

Flagpole-sitter Bill Sherwood descended from his perch on September 19, 1955. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

On September 8 at County Stadium, the Dodgers clinched the National League pennant in their 138th game—earlier than any team ever had. Whether from not participating in a pennant race or because it was one of Milwaukee’s hottest summers on record, the Braves fell short of a third consecutive season of record-breaking attendance. Although 2,005,826 fans continued to ride the roller coaster of emotions hinging on the outcome of every game, critics began to question if Milwaukee still held an enthusiastic appetite for baseball. But team officials continued to be optimistic about the team’s future, noting that when the Braves won, it was like a tonic to the town, while a losing streak created a depressed funk on the city streets. “On a long-term basis,” Lou Perini told reporters, “there may be some leveling off in attendance. But it is not a novelty. There is a real, wholesome enthusiasm for baseball and fewer distractions in Milwaukee and the state.”

On April 20, 1955, right-hander Humberto Robinson debuted with the Braves, the first native of Panama to reach the majors. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Despite the slight dip in attendance in 1955, County Stadium had nearly six million paid admissions over its first three seasons. The county collected approximately $471,000 in revenue from gate and concession receipts during that time. The stadium’s ample parking lots alone earned the county more than $500,000 between ’53 and ’55. In total, Milwaukee County grossed over $1,078,000 during County Stadium’s first three years of operation. The contract between the club and county also stipulated that the county receive a payment of 5 percent of gate and concession receipts, which in 1955 amounted to $195,989.91. Such prosperity in a city whose metropolitan population was only 871,047 left every baseball owner pondering the prospects of franchise relocation.

There was plenty of music aboard the Braves Booster Club train that traveled on a ten-day tour of New York, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn to support the team. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

As the season concluded, Milwaukee shook off the 1954 world champion New York Giants to settle for second place a distant thirteen and a half games behind Brooklyn, with a respectable 85–69 record. “Aaron and Mathews had great years, but they couldn’t carry the load,” Grimm said. “When the season started, I thought we had the best pitching, the best infield, and the best outfield in the league. Statistics proved otherwise.”

As critics began to question if the Braves would ever seriously contend for a pennant, even Grimm noticed the public’s optimism beginning to waver. “I thought the notices were a bit premature, though I had been around long enough to realize that the manager is the sacrificial lamb when the public starts wondering what’s holding back the team,” he said. “By this time, in the third season in Milwaukee, the fans were becoming impatient for a pennant.”

♦ ♦ ♦

The Braves’ 1956 spring training camp atmosphere was clouded with doubt from the start. Labeled an enigma by baseball prognosticators, Milwaukee was expected to finally overcome injuries that had overshadowed its potential in seasons past. After three bittersweet years for the Braves in Milwaukee, critics boldly declared that the fate of manager Charlie Grimm rested on the team’s ability to clinch a pennant. Although his club had finished second, third, and second, respectively, in his three seasons at the helm in Milwaukee, Grimm’s managerial style was increasingly criticized. “He gave players a free rein, feeling that they were professionals who would not take advantage of him. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way. Charlie knew the game, but he was too lenient with the Braves,” Donald Davidson noted in Caught Short.

During spring training, Grimm maintained his theory that players make the successful manager, but he adjusted his once-conservative and predictable management style around the Braves’ emerging strengths: speed, pitching, and power. “When the 1956 season opened, I was confident we would go all the way,” Grimm remarked.

Charlie Grimm offered cigars to pitchers Phil Paine, Carlton Willey, and Lou Burdette during 1956 spring training. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

It seemed that as long as everyone stayed healthy, the Milwaukee Braves’ new All-Star-filled lineup couldn’t miss winning the pennant. Their hitting attack, anchored by Henry Aaron, Joe Adcock, and Eddie Mathews, was one of the most fearsome middle-of-the-lineup alignments in all of baseball. Their ageless wonder, Warren Spahn, looked to continue dominating National League hitters, while Bob Buhl was expected to fully rebound from an injury that had shortened his 1954 season. To ensure that the Braves played up to expectations, Perini appointed former Pittsburgh Pirates manager Fred Haney to Grimm’s coaching staff. “Certainly, Haney was there as a backup. He had managerial experience with a couple of teams in the big leagues,” Milwaukee Braves’ historian Bob Buege recalled.

After finishing their daily spring training workouts, Braves (from left to right) Red Murff, Del Rice, Dave Jolly, and Sam Taylor pooled their efforts at a Bradenton billiards parlor. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Back in Milwaukee, loyal Braves fans were eager to dethrone the National League juggernauts, and more than 900,000 tickets were sold before Opening Day. “Expectations were high for the Braves in 1956, both our own and the fans.’ We thought we had as good a team as Brooklyn, or better,” Eddie Mathews declared.

At the April 17 home opener, 39,766 fans watched Lou Burdette shut out the Cubs 6–0. Behind the pitching talents of Spahn, Burdette, and Buhl, Milwaukee won its first three games en route to nine of its first twelve. By the beginning of May, Grimm’s Braves had claimed first place after holding off the rest of the National League for nearly a month and boasted a 19–10 record.

Although they were performing at an exceptional level, the Braves couldn’t separate themselves from the rest of the National League. With no team trailing first place by more than three and a half games, the 1956 pennant race quickly shaped up as one of the most exciting in National League history. No team could establish itself as a clear favorite, and the Braves, Dodgers, Redlegs, Cardinals, and Pirates all were battling for first into June. The pressure continued to mount on Milwaukee, fueled by New York writer Milton Richman, who predicted that “Charlie Grimm will have the Milwaukee Braves in first place by June 15, or he’ll be out of work.”

Questions surrounded the Braves’ pennant aspirations in 1956. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 139)

Knocked off the top of the standings in early June by the Pirates, Milwaukee went on to drop nine of thirteen games—and ended up reeling in fifth place at 24–22. By June 16 word of a management change began to spread among the players. “Before the game started against the Dodgers in Brooklyn, I sensed that something was in the air,” Grimm recalled. “The Perinis and other club officials were sitting in a box next to our dugout and newspapermen were interviewing them like mad. I was trying to pay strict attention to the action after the game started, but it didn’t escape me that the players were whispering among each other on the bench.”

Two days later the Braves dropped a 3–2 decision to the Dodgers after allowing two unearned runs and an eighth-inning home run to Duke Snider. Following the frustrating loss, Grimm resigned. “I’ve decided to let someone else take a crack at the job,” Grimm told reporters at the press conference. “Anyone who can win ten or eleven in a row can win this thing.”

Frustrated with the Braves’ underachievement in the standings, Perini replaced Grimm with Fred Haney. Haney fully realized the difficult situation he had inherited. “This is the toughest job I’ve ever faced. I mean it!” he commented to reporters. “These fellows are spoiled rotten. When you take a team to spring training, you can get things the way you think they ought to be. But in mid-season you can only do so much; otherwise you may have something on your hands that you don’t want. This situation can be worked out, but not overnight.”

In frigid February temperatures, Braves fans came well prepared with blankets and supplies to keep comfortable and warm while waiting more than two days outside County Stadium for 1956 season tickets to go on sale. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Haney had a reputation for being a good skipper with bad teams, having spent unsuccessful managing tours with the St. Louis Browns and Pittsburgh Pirates. While nobody knew if having Haney at the helm made the difference, or if Jolly Cholly’s exit had served as the wakeup call, the Braves’ performance began to take a turn. The Braves were in fifth place and four games out of first when Haney took the reins, but the club didn’t stay there for long. “There is something magic about a change, though. I can’t deny that,” Aaron said. “We got cranked up again. All we needed was a kick in the britches.”

Youngsters Michael Rodell and Thomas Greiner were left frustrated after a game at County Stadium was canceled due to inclement weather. (COURTESY OF MIKE RODELL)

During Haney’s first game as skipper, Joe Adcock once again proved Ebbets Field was his favorite playground. He connected for three home runs, including a towering, game-winning homer in the ninth inning. “Sweeping the Dodgers that day gave us confidence, and all of a sudden we couldn’t lose,” Eddie Mathews said.

Milwaukee went on to win nine more games in a row before dropping a 4–2 decision to Robin Roberts on June 26 in Philadelphia. During their eleven consecutive victories, the Braves catapulted themselves from three and a half games out of first to a two-game lead over the rest of the National League. A reluctant Haney refused to take the credit. “Believe me, I’m no miracle man,” he told reporters. “The Braves themselves deserve the credit for their winning streak. Don’t give me any of it.”

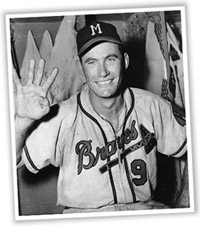

Fred Haney (right) held a number 10 jersey alongside pitcher Gene Conley to signify the Braves’ tenth straight win since he took over as manager. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

By the All-Star break Milwaukee cooled, and the pennant race became a tight three-team battle with only three games separating first from third. The Redlegs held the National League lead, with the Braves in second and the Dodgers right behind.

Baseball’s twenty-third annual All-Star Game was held in Washington, D.C.’s Griffith Park. Four Braves were selected to the National League roster. The game featured an at bat by Henry Aaron and two innings pitched by Warren Spahn, who gave up the only three runs the American League scored in the Nationals’ 7–3 victory. A slumping Eddie Mathews rode the pine, and catcher Del Crandall was replaced due to an injury. “I chipped some bones in my left elbow,” the Braves’ catcher recalled. “But it might have been a blessing in disguise. I had to cut down my swing as a result and maybe became a better hitter because of it.”

In a thrilling second half of the season, the Braves won fifteen of their first seventeen games. The club’s surge paralleled Joe Adcock’s assault on opposing pitchers as he connected for ten home runs in thirteen consecutive games. So it was no surprise when on July 17 the Giants tried to slow him down the only way they knew how—by throwing at him. Ruben Gomez’s first pitch in the second inning struck Adcock on the same wrist that had been broken a year earlier. “Joe started down to first base rubbing his bicep and mumbling to himself. About halfway there, Gomez for some reason started screaming at him. That just triggered Joe,” Eddie Mathews recalled. “He was never going to start anything. But whatever Gomez said to him—it ticked him off because he charged the mound.” Adcock’s otherwise-easygoing persona boiled into an all-out rage. “When Joe charged the mound, Gomez cranked up and hit him again with the damn thing, harder than the first time but this time on the front of his thigh.”

Adcock chased Gomez off the mound and into the Giants’ clubhouse. “Gomez went in there and got an ice pick,” Johnny Logan remembered. “The guys on his own team had to stop him.” After the incident, both men were ejected, and the Braves eventually lost the game in twelve innings. Two days later Adcock followed up by continuing to pummel the Giants, this time with his bat. After driving in eight runs with a grand slam, a three-run homer, and an RBI single, he was finally taken out of the game after six innings in the 13–3 Braves win.

By the end of July, Milwaukee held a five-and-a-half-game lead. Behind the dynamite performances of Aaron, Adcock, and Mathews, the Braves established a major-league record on July 31 by hitting a home run in their twenty-second consecutive game. The threesome’s contrasting styles at the plate reflected their personalities. Aaron was the wrist hitter, with any pitch susceptible to being driven into play in an instant. Mathews was the stylist, his stance, swing, and coordination flirting with perfection. Adcock lacked both wrist action and stylistic panache, but his massive arms, swinging hips, and thrusting head generated awesome power.

The 1956 season found the Braves entangled in another highly contested National League pennant race. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 270)

Helping to hold the Braves’ lead over Cincinnati and Brooklyn into August was a healthy Bob Buhl. “He was a nasty pitcher and a fierce competitor,” Aaron observed. “Spahn and Burdette had been so good for so long that people didn’t realize how much Buhl meant to us.”

The Saginaw, Michigan, native had walked away from a pugilistic career after he knocked a boxing rival so cold he wasn’t sure if his opponent would recover. “Until that happened,” Buhl recounted, “I thought I might make boxing my career. But when I saw him lying on the canvas, out cold, I never wanted to see a boxing ring again.” Buhl turned to baseball—and became one of the Braves’ most potent arms. “When I joined the club,” Braves backup catcher Del Rice told Sport magazine, “he was just a thrower. Now he’s a real pitcher, the best in the league in my book. He’s got a lot of good pitches—curve, slider and change-up, besides a fast one. He even throws a knuckler once in a while. He’s got the batters looking for his fastball and he’s fooling ’em with the other stuff.”

In 1956 Henry Aaron (44) led the league in hits, doubles, and total bases and finished just one triple behind Billy Bruton. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The Dodger-slayer chalked up eight victories and a stifling 2.43 earned run average against the defending world champions in 1956. “Let’s face it,” Buhl admitted. “If you don’t have luck, you can’t win. You can pitch two-hitters and three-hitters until you’re blue in the face and you’ll still be a losing pitcher. Look at my record this year and you’ll see what I mean. I’m just plain lucky.”

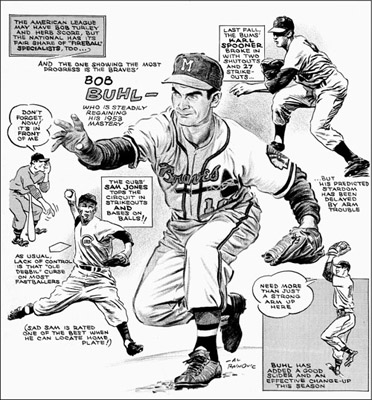

Bob Buhl finished with the second-highest winning percentage in the National League in 1956, with an 18–8 record. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 238)

But on August 4 in Pittsburgh, Buhl suffered a fractured finger when he was struck by a line drive. He pitched the final two months of the season in less than top condition and limped to an 18–8 record. With Buhl ailing, Milwaukee ventured to Philadelphia’s historic Connie Mack Stadium for a crucial four-game series. After Henry Aaron knocked in the game-winning RBI in the thirteenth inning to secure the 3–2 victory in the first game of a doubleheader, Warren Spahn dueled Robin Roberts for twelve innings in the nightcap. Aaron hit another a game-winning RBI in the twelfth inning for the 4–3 victory.

The win was Spahn’s two hundredth career victory, securing his place as the fifty-eighth pitcher to join the distinguished two hundred–wins club. At an age when most pitchers retired their worn-out arms, thirty-five-year-old Spahn continued to thrive on the mound with an unwavering will to win. After eleven seasons, his fastball was no longer as swift as it once was, but his control and patience continued to baffle enemy batsmen. As he often explained, “The more I pitched to a hitter, the less I was impressed by him.”

Following a doubleheader sweep of the Phillies, the Braves dropped their next two games in Philadelphia and on September 15 fell out of first place by percentage points for the first time since July. For the rest of the month, the Braves were in and out of first place, but they went into the last three games of the season a full game ahead of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Milwaukee was in control of its own destiny as the pennant hung in the balance. “We had it. It was right there in our laps,” Aaron said.

Needing to win only two of their last three games to guarantee at least a tie with the Dodgers for first place, Haney had his aces—Buhl, Spahn, and Burdette—lined up to pitch in St. Louis. But on September 28 the Cardinals trounced Buhl early en route to a 5–4 victory. With the Dodgers rained out in Pittsburgh that night, the Braves lead was down to half a game. Yet regardless of what Brooklyn did, the pennant was still Milwaukee’s if they could win their final two games. The following day the Braves players were left to squirm in their hotel rooms as the Dodgers catapulted themselves into first place. “That was the key game,” Aaron said. “You see, we went into it knowing that the Dodgers had taken a doubleheader from Pittsburgh that afternoon. The heat was on us.”

In 1956 Bob Buhl, Warren Spahn, and Lou Burdette hurled eighteen, nineteen, and twenty wins, respectively, for the Braves. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

For the third consecutive season, the Braves drew more than two million fans to Milwaukee County Stadium in 1956. (COURTESY OF BOB BUEGE)

The Milwaukee Braves boosters supported the team during crucial road trips, including an August 1956 series against the Dodgers at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Despite losing two of their final three games and the 1956 pennant, the Braves and manager Fred Haney (in headdress) received a hero’s welcome at General Mitchell Field upon the team’s return from St. Louis. (WHI IMAGE ID 49354)

That night the Braves took the field confident they’d be back in first place, especially since their ace was looking to capture his twenty-first victory of the season. “Warren Spahn pitched his guts out in St. Louis,” Henry Aaron recalled. “The Cards got only three hits in eleven innings.”

But with one out in the bottom of the twelfth, the Cardinals finally got to Spahn. After Stan Musial doubled and Ken Boyer was intentionally walked, Rip Repulski drove a shot down the third-base line that the Braves’ Eddie Mathews attempted to field. “All I was trying to do was get in front of it to block it,” Mathews explained. “I didn’t know where the hell the bounce was going to come. It hit me in the knee and bounced into foul territory and over to the stands.”

When the ball caromed off Mathews’s knee, Stan Musial scored the winning run. It was a devastating 2–1 loss for the Braves. As Spahn headed to the dugout, tears flowed freely down his cheeks. “Beyond a doubt, that Saturday game in St. Louis was the most heartbreaking moment I had in twenty-one years of baseball,” Spahn remembered. “We had every reason to win, but it was like it wasn’t meant to be.”

Even Henry Aaron’s league-leading .328 batting average couldn’t save the team’s evaporating pennant hopes. “We might as well have left our bats in the clubhouse,” he said in his 1974 autobiography. “To this day, I believe we should have won the pennant that year, but we choked.”

As expected, the entire Braves organization took the loss hard. “After the game, Quinn and I went to the top of the Chase Hotel for a drink,” publicity director Donald Davidson remembered. “John looked out the window and said to me, ‘Do you want to jump first, or do you want me to push you?’ ”

For the Braves’ 1956 season finale, Burdette beat the Cardinals 4–2, but it was too late. Brooklyn had already completed the series sweep of Pittsburgh to repeat as National League champions. “We led the league 126 days. The Dodgers led the league only 17 days, but they led the last day and that was the right day,” Aaron observed. “Man, you talk about something hurting. For the first time in my life in the big leagues, I really knew what hurt was.”

As the players quietly dressed, Fred Haney entered the clubhouse. With their 92–62 record falling one game short of the pennant—their third second-place finish in four years—Milwaukee was again without an elusive World Series appearance. Instead of receiving a courtesy thank you and congrats, the players received a reception of cold conviction. “Boys,” Haney told them. “Go home and have yourselves a nice winter. Relax. Have fun. Get good and rested, because when you get to Bradenton next year, you’re going to have one helluva spring.”