The Braves of Bushville featured an eclectic roster, including the future all-time home-run king, a future NBA champion, six future big-league managers, and four future Hall of Famers. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

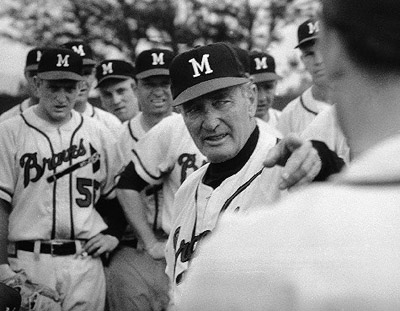

When Fred Haney called a team meeting before the first day of 1957 spring training, the Braves quickly realized the season would be vastly different from years past. Accustomed to “Jolly Cholly” Grimm’s easygoing managerial style, the players gathered around expecting to hear an energetic pep talk. Instead, the Braves’ manager made good on his promise from the previous September of giving them “one helluva spring.” For six weeks Haney put the players through hours of practice and extensive conditioning, often followed by intrasquad games. He left no room for excuses or exceptions during his militant workouts. “We were there to practice being perfect, and the less perfect we were the better shape we got into,” Henry Aaron recalled in his autobiography Aaron. Whenever an error was made, during either practice or intrasquad games, the entire team dropped what they were doing and ran a lap around the ballpark. “By the time we broke camp,” Aaron said, “I swear that I knew every blade of grass around that fence by its first name.”

Milwaukee was considered the odds-on favorite to win the 1957 National League pennant, and Haney refused to watch the Braves endure another pennant-race collapse. “With the experience of last year,” Haney told reporters during spring training, “with the entire nation pulling for us and the wonderful reaction of the Milwaukee fans who met us at the airport on our return from St. Louis after losing, I think it would take a man with a heart of stone not to have the determination to bring a winner to these wonderful people.”

By the time Fred Haney’s Braves broke camp in Bradenton, they were slim, trim, and hungry to vindicate themselves after the previous season’s disappointing finish. “I don’t think I ever saw a team open a season as determined to win as we did in 1957,” Aaron said.

Braves manager Fred Haney (pointing) was called “Little Napoleon” by many of his players due to his 5’6” stature and strict workout regimens. (WHI IMAGE ID 49246)

Thirty-six-year-old Warren Spahn took the mound for the Braves in the opener at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. Fully recovered from several off-season cartilage operations on his knees, Spahn continued to dominate National League batsmen. The Braves ace retired the last fourteen men he faced en route to a four-hit, 4–1 Opening Day win. “I think he can pitch a couple more years, anyhow. He doesn’t have the blazing stuff anymore, but his knowledge of the hitters is a big help to him,” Haney admitted to reporters. “Spahnie goes on like ol’ man river because he works hard to keep in shape.”

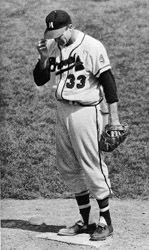

The Braves started the 1957 season uncharacteristically fast, winning their first five games. The streak included their fifth consecutive home opener victory at County Stadium as Lou Burdette hurled a six-hit shutout against Cincinnati. Burdette’s gestures, mound antics, and delivery often suggested he was throwing an illegal spitball. “The way I described it is he threw a ‘dry spitter,’ ” Del Crandall explained. “His ball just moved down a lot. He had a great sinker. Some hitters were always complaining. It was laughable. Lou just threw sinkers, sliders and screwballs.”

With his fidgeting mannerisms, Burdette inspired Fred Haney to suggest that “Lou would make coffee nervous.” Opposing teams often scrutinized the right-hander as he went through countless gyrations between pitches, leading hitters to believe the ball was wet—even if it wasn’t. “I don’t believe Burdette ever had an interview when he wasn’t asked if he threw a spitball,” Donald Davidson said. “He had a standard answer: ‘I don’t know how you guys can ask me a silly question like that. They always accuse me of throwing it. I never did even though I’ve been told by hitters that certain pitches I threw did funny things on the way to the plate. Having the batters think I was throwing spitters gave me a psychological advantage.’ ”

Fred Haney (2) with his Braves coaching staff (from left to right) Charlie Root, Connie Ryan, John Riddle, and Robert Keely (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Nobody was more accusatory of Burdette’s supposed cheating than Redlegs’ manager Birdie Tebbetts. The Cincinnati skipper was so determined to catch Burdette in the act of doctoring the ball that on April 27 he had slow-motion cameras placed around Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. Unable to gather any substantial proof, Tebbetts and the Redlegs were forced to watch Burdette beat them 5–4 behind homers from Henry Aaron and Joe Adcock.

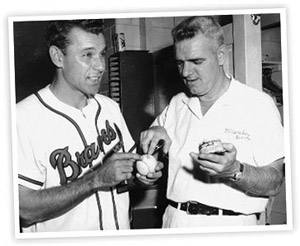

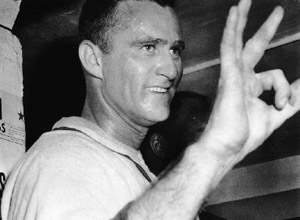

Lou Burdette was known for quick gestures to his cap, mouth, and forehead that deceived many paranoid hitters—and helped him post a 17–9 record with a 3.72 ERA in 1957. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

During those first ten games of the season, the Braves built an early three-game lead almost solely on the arms of Spahn and Burdette. Managing the schedule to take advantage of open dates, Haney kept his two aces on the mound, while Bob Buhl, Ernie Johnson, Red Murff, and Dave Jolly saw minimal action during the first few weeks of the season. “I worked my men in spring training with that in mind,” Haney told the press. “I worked the others, too—in batting practice, running them in the outfield. And I explained my intentions to them. You’ve got to be honest to gain confidence.”

But Haney’s strategy soon sputtered as the Braves fell into a malaise. After Cincinnati won nine games in a row to catapult past Milwaukee in the standings, Haney called out his entire team during a closed-door meeting in May and told them, “You’re playing like you played last September.”

By mid-June the Braves had slid down to fourth place in a five-team pennant race, with only two and a half games separating the front-running Redlegs from the fifth-place Cardinals. With tension rising in the Milwaukee clubhouse, the team needed a spark. Tempers finally boiled over in Brooklyn on June 13, when Billy Bruton’s second home run of the day led to the Dodgers’ Don Drysdale flagrantly planting a fastball in Johnny Logan’s ribs. As the Braves’ feisty shortstop trotted to first base, he glared at the Dodgers hurler from under his bushy black eyebrows. “Try coming into second base some time,” he yelled, adding a few choice phrases regarding Drysdale’s ancestry.

Milwaukee Braves “bonus babies” Hawk Taylor (19), Mel Roach (29), Joey Jay (42), and John DeMerit (18) signed in an era when there was a wide-open market for amateur players. In an attempt to keep signing bonuses under control, players who received more than a $6,000 reward for turning pro were prohibited from being sent to the minor leagues for two years. The flawed system often prevented players from maturing in the minors and eventually led to the birth of the amateur draft. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

“Why wait?” Drysdale defiantly replied. “Let’s do it now.”

Never one to back down from a fight, Logan charged the mound. Eddie Mathews, who had been watching from the on-deck circle, raced onto the field to back up his teammate. “Eddie did not start many fights, but he finished several,” Donald Davidson reminisced. “Mathews rescued Logan so often that they called him John’s relief fighter.”

The Braves’ fearless third baseman knocked down Brooklyn’s towering rookie pitcher with one wicked right hook. Not until Brooklyn’s Gil Hodges dragged Mathews away by his ankles did the pummeling of Drysdale cease. The fight seemed to ignite the Braves, and a Carl Sawatski home run helped Milwaukee beat Brooklyn to put them atop the National League standings for the first time in nearly a month.

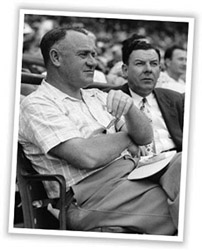

With the midseason trading deadline about to expire on June 15, general manager John Quinn still sought the magic formula that would stabilize the inconsistent Braves. He decided the team was in need of some veteran leadership with postseason experience. As the midnight trade deadline approached, Quinn finalized a deal that sent frontline players Bobby Thomson, Ray Crone, and Danny O’Connell to the Giants for second baseman Red Schoendienst. “When we traded for Red, that solidified our infield. He knew talent and would position different fielders accordingly. He was like a manager on the field,” Braves’ veteran outfielder Andy Pafko recalled. Arriving with a reputation as a smooth fielder and tough hitter from either side of the plate, Schoendienst immediately took O’Connell’s place on the roster. Looking to fill the holes left by the departed Thomson and Crone, Milwaukee called up power-hitting Wes Covington to platoon in left field and twenty-seven-year-old hurler Don McMahon to provide some much-needed late-inning relief.

Johnny Logan (23) hurled punches at any Dodgers that got in his way during a June 13, 1957, brawl. (COURTESY OF MIKE RODELL)

Braves owner Lou Perini and general manager John Quinn (WHI IMAGE ID 49051)

Then on June 23 at County Stadium, Joe Adcock broke his right leg while sliding into second base, sidelining him until September. “I’m surprised that Joe hadn’t broken something before when he slid,” Aaron recalled. “He was a lot of a man, and when he hit the dirt it was like a horse sliding. You could almost feel the ground shake.”

In need of an immediate replacement, the Braves turned to Brooklyn native Frank Torre. Known more for his glove than his bat, he did little to boost hopes that Milwaukee would capture the pennant in 1957. “We were in second place,” Torre remembered, “and all the media sort of kissed us good-bye.”

Right before the All-Star break, the Braves continued to slump, losing five of seven games and dropping two and a half games behind the first-place Cardinals. Once again, Milwaukee was well represented during the Midsummer Classic at St. Louis’s Sportsman’s Park, with Henry Aaron, Lou Burdette, Johnny Logan, Eddie Mathews, Red Schoendienst, and Warren Spahn selected to the All-Star squad. Despite their efforts, the National League lost 6–5.

Reserves Frank Torre and Nippy Jones played vital roles in the Braves’ quest for the 1957 National League pennant. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The pennant race reconvened with the Cardinals, Braves, Dodgers, Redlegs, and Phillies desperately trying to put together a winning streak. With the slightest injury or lapse in judgment forfeiting a team’s chances, the Braves thought they watched their pennant hopes literally crash onto the outfield grass on July 11, when Billy Bruton collided with shortstop Felix Mantilla while chasing a pop fly into short center field. “I was goin’ at full speed and Bruton was comin’ at full speed,” Mantilla recounted. “We collided, and I went like fifteen feet up in the air and Bruton went the other way. It was ugly.” Both players got up with a little help, but the damage was done. Mantilla’s injury kept him out of nineteen games. Bruton’s torn right knee ligaments left him on the disabled list for the remainder of the season. Two days later, outfield replacement Andy Pafko got hurt while making a sliding catch. “All of a sudden Del Crandall had to take off his mask and chest protector and become a right fielder,” Braves historian Bob Buege explained. “Even recently acquired second baseman Red Schoendienst and first baseman Nippy Jones had to take their turns as fly-catchers.”

Desperate for outfield assistance, the Braves were about to call up Earl Hersh from their Wichita farm club. Instead, Wichita manager Ben Geraghty lobbied for Bob Hazle and his hot bat to be given a chance. After being acquired by Milwaukee the previous season in a trade with the Cincinnati Redlegs for George Crowe, Hazle had almost quit baseball but decided to play one more season. He started the 1957 season at Wichita and was hitting just .220 when he suddenly caught fire and Geraghty recommended him to be called up. Nicknamed after a storm that hit the South Carolina coast in 1954, Bob “Hurricane” Hazle was supposed to ride the Braves’ bench as outfield insurance but soon found himself storming through National League pitching rotations. “I don’t know what happens to suddenly make a minor league ballplayer into Babe Ruth,” Eddie Mathews confessed, “but Hazle was right out of ‘The Twilight Zone.’ We were hanging in there pretty well before he arrived, but he just picked us up.”

Beginning on July 31, the Braves went on to win the first nine games Hazle started, and by August 6 the team had regained first place. Before anyone could stop the Braves in mid-August, they had won ten games in a row, all by lopsided scores. Even the Dodgers couldn’t slow them down. On August 24 the Braves tore through eight Brooklyn pitchers during a 13–7 thrashing, tying the National League record for most hurlers used in one game. The following day, Bob Hazle, who had been hitting a blazing .526 since being called up, hit two two-run homers as Warren Spahn beat the Phillies.

Milwaukee’s firepower continued to devour opposing pitching staffs. On September 2 the Braves whipped the Cubs at Wrigley Field in a doubleheader sweep. Bob Hazle showed no signs of slowing down after going four-for-seven in the first game, with three doubles and two RBIs in Milwaukee’s 23–10 pummeling. “He was hotter than a firecracker. Every time he swung the bat, it seemed like he got a base hit,” Red Schoendienst remembered. Frank Torre, still subbing at first base for the injured Adcock, tied a major-league record by scoring six of the Braves’ twenty-three runs. In the second game Bob Trowbridge hurled a masterful three-hitter as Milwaukee handcuffed the Cubs’ bats in a 4–0 shutout. The following day Spahn whitewashed Chicago, 8–0, for his forty-first career shutout, setting a career record for left-handed pitchers.

Hitting .403 in 134 at bats in 1957, Bob “Hurricane” Hazle joined Ted Williams, who hit .406 in 1941, as the only two players to hit .400 in at least 150 plate appearances since 1930. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The Braves finally cooled after Labor Day, but not before winning seventeen of nineteen and twenty-four of twenty-nine games to build an eight-and-a-half-game lead. By losing eight of eleven in a September slump, the Braves allowed St. Louis to shave six games off their lead. “We lost enough ballgames in September to keep it interesting,” Mathews admitted.

On September 15, following their third straight loss, the Braves’ lead was down to just two and a half games. “Terrible nightmares of 1956’s final weekend collapse began to recur among the Milwaukee faithful,” Bob Buege observed.

Following the loss, Haney kept the clubhouse door closed for an hour. When he finally opened it, reporters and photographers burst into the room. Haney turned to his players and reminded them of just what would happen if the team continued to slide. “Here are your pallbearers, gentlemen. Don’t you want to meet your pallbearers?”

Following the meeting, the team won five straight behind a revived pitching staff. Bob Buhl, Bob Trowbridge, and Lou Burdette won complete games, and Warren Spahn won his twentieth game of the season, followed by Buhl’s second victory within five days.

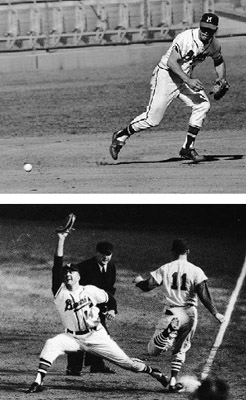

Eddie Mathews’s fielding and cannon arm at third base (above) continued to improve as he led the league in assists, while across the diamond first baseman Frank Torre (below) led all National League first basemen in fielding percentage in 1957. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

With six games remaining, the Braves had a five-game lead over the second-place Cardinals. Arriving in Milwaukee for a three-game series, St. Louis was looking to keep its pennant hopes alive with a series sweep. “After what happened in 1956, we were taking nothing for granted. We had shown that we were capable of choking, and deep down everybody was afraid it might happen again,” Aaron confessed.

An anxious crowd of 40,926 fans filed into County Stadium for the series’ first game on September 23. Milwaukee jumped off to a quick 1–0 lead in the second inning, while Burdette kept St. Louis off the scoreboard for the first five innings. After yielding a pair of runs in the top of the sixth, the Braves tied the game at two in the bottom of the seventh. With the game still tied after nine innings, Milwaukee appeared poised to win in the tenth inning after loading the bases with one out—until pinch hitter Frank Torre bounced into a rally-killing double play. “The crowd was so deflated at that point,” recalled future baseball commissioner Bud Selig, who was in the County Stadium stands that night.

After Red Schoendienst made the first out in the home half of the eleventh inning, Johnny Logan kept the Braves’ pennant hopes alive with a single to center. When Eddie Mathews proceeded to fly out, the crowd grew even more anxious. “Everybody was shouting and throwing something, and County Stadium was losing its mind,” Henry Aaron recalled. “But I remember looking up about halfway down the first base line and noticing the time on the big clock hanging above the fence. It was 11:34.”

By 1957 the Braves Booster Club was the largest in baseball, with more than thirty thousand estimated members. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

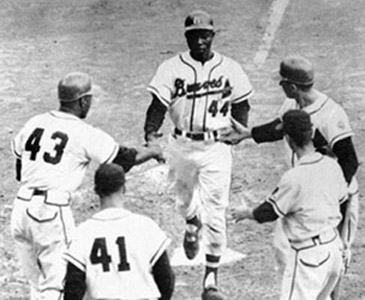

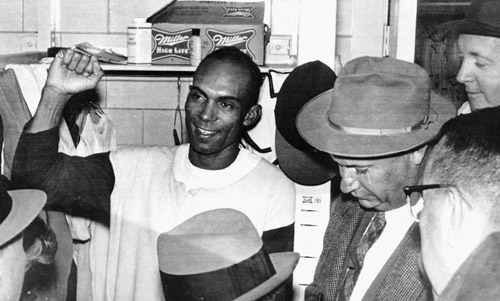

Aaron stepped into the batter’s box to face Billy Muffett, who was fresh from the Cardinals’ minor-league affiliate in Houston. On his first pitch, Muffett threw a slow curve hoping Aaron was expecting a fastball. Aaron’s quick wrists adjusted, and he connected on the pitch—a towering hit toward the center-field fence. At the 402-foot sign, St. Louis outfielder Wally Moon reached the wall and leaped. For an instant it appeared he had caught the ball, but as fans scrambled to retrieve the souvenir, everyone knew Aaron had clinched the Braves’ pennant. “When Hank hit that pitch, I knew it was a homer,” Lou Perini told reporters following the game, “but it was the slowest homer I ever saw in my life. I thought it would never get over the fence.”

County Stadium erupted! The Milwaukee players stormed out of the dugout under a rain of newspapers, scorecards, streamers, cups, hats, and various articles of clothing. As Aaron circled the bases, he realized the significance of his blast. “I think that was my biggest home run,” Aaron acknowledged four decades later. “People ask me why and I tell them, ‘Milwaukee had never won a pennant.’ That was our first time. You never forget that.” When he reached home plate, Aaron was lost in a crush of delirious teammates and then thrust onto their shoulders for a hero’s ride off the field. “I can’t tell you who was carrying me because you know something? I don’t remember that at all. But I remember looking up at that clock and seeing 11:34.”

Henry Aaron’s 109th career home run clinched Milwaukee’s first National League pennant. (COURTESY OF MIKE RODELL)

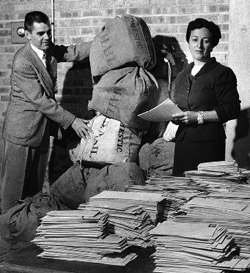

Braves ticket director William Ebberly and Marion Kleiner examined the World Series ticket applications that flooded County Stadium on the morning of September 18, 1957. They estimated that the post office had already delivered twenty-nine bags of mail, containing nearly 47,600 pieces. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Inside the Braves’ clubhouse, champagne corks popped and players and coaches doused each other. Even the usually reserved Lou Perini squeezed manager Fred Haney in a tremendous bear hug. Within minutes the news had spread all over town. Milwaukee was immersed in a raucous chorus of blaring horns, bells, and sirens as one of the wildest celebrations in baseball history screamed into the early hours of the morning. “Parties literally continued for days. I know, because I attended them,” remembered publicity director Donald Davidson. “It was a night to remember—if you could the next day.”

The Braves had finally delivered a pennant to Milwaukee, and the city continued enjoying the financial benefits of the Braves’ winning ways. When the final numbers were tallied, Milwaukee County Stadium’s 2,215,404 fans had established another astounding attendance record. With the team operating under a contracted formula that gave the county 5 percent of the admission and concession receipts, County Stadium rent in 1957 cost the club $216,000. The county made another $150,000 from parking lot receipts (having charged only twenty-five cents per car). As for the financial intangibles, a study by the Association of Commerce indicated that the Braves had brought about $8 million into Milwaukee in 1957 and over $34 million since their relocation from Boston. After five seasons, 453 victories, and 10,225,356 fans through the County Stadium turnstiles, Milwaukee was World Series bound.

As County Stadium prepared to host its first World Series, a workman high atop an extension ladder put the finishing touches on a tepee of heroic proportions. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Although the Braves had established a club record with 95 wins, they hadn’t yet fully achieved their preseason goals, according to Haney. The team’s next assignment was an engagement with the perennial American League champion New York Yankees. The Bronx Bombers had won ninety-eight games in 1957 and finished a commanding eight games ahead of the second-place White Sox. Treating the Fall Classic as their personal property, the Yankees had been in eight of the previous ten World Series, winning seven of them. Winners of more world championships than any other club in baseball history, the Yankees were considered a faceless, bloodless machine by everyone except their die-hard fans. Boasting an awesome collection of Series veterans including Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Moose Skowron, Whitey Ford, and skipper Casey Stengel, the Yankees were the odds-on favorites. “We knew it was going to be tough, playing the Yankees,” pitcher Gene Conley admitted.

The 1957 Braves established a franchise-record 199 homers and led the league in runs and triples while finishing with a .269 team batting average behind the bats of (from left to right) Eddie Mathews, Henry Aaron, Bob Hazle, Don McMahon, and Wes Covington. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Relishing their role as underdog, the Braves believed they were the perfect candidates to silence the famed Yankee bats. “I felt good about our chances in 1957,” Andy Pafko remembered. “If you looked at that club man-to-man, they were all stars. I was fortunate to play with a lot of great players who enjoyed playing baseball. We had the talent, but it boils down to pitching, and we had Warren Spahn, Lou Burdette, Bob Buhl, and Gene Conley.”

During the Braves’ pre-Series workout, Yankee Stadium had a carnival atmosphere as hundreds of reporters pressed the players for quotes. Except for Spahn, Schoendienst, Pafko, and reserves Nippy Jones and Del Rice, this would be the first World Series appearance for any of Milwaukee’s players. Regardless, they all realized whom they were about to face. “I’m standing on the top step of the visitors’ dugout in Yankee Stadium and I just froze,” Pafko confessed. “The greatest players in the world played for the Yankees—DiMaggio, Ruth, and Gehrig. And here I am, a little country boy from Wisconsin playing in the World Series. I still get goose bumps talking about it.”

♦ ♦ ♦

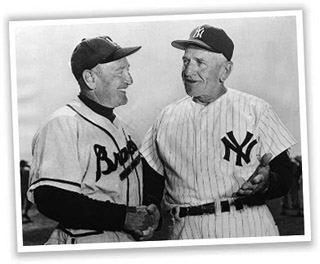

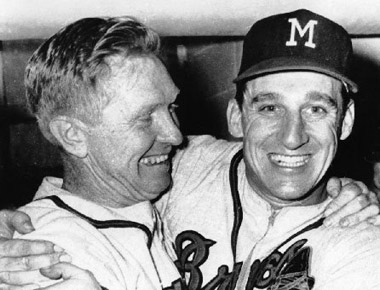

World Series managers Fred Haney of the Braves and Casey Stengel of the Yankees (WHI IMAGE ID 25507)

Game One of the 1957 World Series opened with all the pomp and circumstance associated with America’s premier sporting event. With red, white, and blue bunting draped over field boxes and world championship pennants from seasons past flying overhead, it was enough to get even the coolest of players rattled. “The Opening Day crowd [of 69,476] didn’t scare us—we were used to big crowds in Milwaukee—but just the idea of playing in the World Series, and millions of people all over the United States watching us on TV, just scared me to death,” Henry Aaron related.

The game showcased two future Hall of Fame southpaws: New York’s Whitey Ford and Milwaukee’s Warren Spahn. During the first six innings, Ford managed to pitch out of a few tight spots to hold the Braves to just two singles. Meanwhile, Spahn became surprisingly ineffective in the Yankees’ home half of the sixth. With one out, New York’s Elston Howard singled, Yogi Berra walked, and Andy Carey singled to center field, driving home Howard as Berra landed at third. It was enough for Fred Haney to replace the team’s ace with trusted reliever Ernie Johnson. After Jerry Coleman put down a textbook bunt, Berra scored just as Johnson fielded the ball, giving the Yankees a 3–0 lead.

In the seventh inning, Wes Covington doubled and scored on a Red Schoendienst single. Despite breaking up the shutout, the Braves were helpless behind Ford’s complete-game five-hitter in the Yankees’ 3–1 victory. With New York taking Game One of the Series in such dominant fashion, prognosticators struggled to imagine the Series going beyond five games. “It looked like we were goners,” Aaron remembered. “They’d beaten Warren Spahn, our best pitcher, and I’d read somewhere that teams that lose the first game of a World Series don’t usually win it.”

For Game Two, most sportswriters fastened onto the irony that Braves starter Lou Burdette had once been Yankees property and, if not for a violent reaction to penicillin, might have still been in pinstripes. Back in 1951, when Burdette had caught a cold during the Yankees’ spring training, he had a severe reaction to the doctor’s penicillin shot and was rushed to the hospital. He languished on the critical list. As his opportunity to impress the parent club closed, Burdette was shipped to the Braves for an aging Johnny Sain in late 1951. The Yankees manager hardly noticed his absence. “Casey [Stengel] didn’t really know I was around. I think I threw two pitches in my whole time in Yankee Stadium.” Burdette recalled. “It was always, ‘Hey, you, get in there and warm up.’ ” Crafting a story line of the castoff coming back to haunt the casters-off, Burdette focused on making sure the Yankees’ skipper would remember and respect him by the end of the Series. He started Game Two and kept the Yankees bats quiet.

Warren Spahn (right) conferred with catcher Del Crandall (left) and manager Fred Haney (center) shortly before being removed from Game One of the 1957 Series. (WHI IMAGE ID 11642)

In the top of the second inning Joe Adcock singled off New York starter Bobby Shantz to knock in Henry Aaron for the game’s first run. The Yankees countered to tie the game in the bottom half of the frame, but in the third inning, Endicott, New York, native Johnny Logan blasted a solo shot into the Yankee Stadium stands to give the Braves a brief 2–1 lead. With the game tied at two heading into the fourth inning, the Braves added two insurance runs. Now with a 4–2 lead, Burdette settled down. “Lou had ice water in his veins. Nothing bothered him, on or off the mound,” fellow pitcher Conley said admiringly. Scattering only four more hits over six scoreless innings, he earned the complete-game victory but downplayed having secured Milwaukee’s first World Series win. “Winning the pennant really was the big thing, wasn’t it?” he asked after the game. “My biggest thrill is any time I get the last man out. That was a big thrill today.”

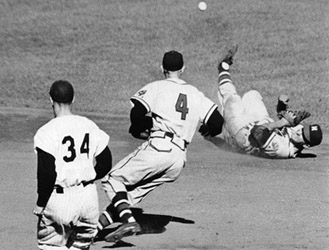

On an infield single by the Yankees’ Elston Howard, shortstop Johnny Logan tried to force out Tony Kubek (34) at second base with a toss to Red Schoendienst (4) during Game Two. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

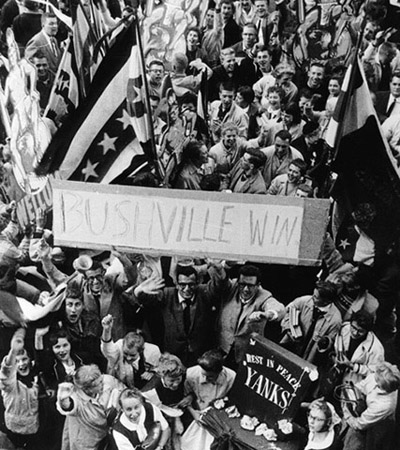

With the Series tied at a game apiece, the Yankees’ arrogant sense of entitlement in the Fall Classic manifested itself before Game Three. It had been widely reported that the Bronx Bombers felt Milwaukee was practically a foreign country inhabited by ignorant fans, and they did nothing to soften their image as their train entered Wisconsin on October 4. After refusing to stop in Sturtevant for a reception in the team’s honor, Yankees manager Casey Stengel let his temper boil over when flashbulbs started popping in his face, spoiling his breakfast. “A few miles out of Milwaukee some newspaper men got aboard, buttonholed manager Casey Stengel, and squeezed some quotes out of him,” Aaron recalled. “He made the mistake of saying something about Milwaukee being a ‘bush town’ and they never let the old man forget it.”

Reports of what happened next conflicted, but whether it was Stengel, Yankees coach Charlie Keller, or trainer Gus Mauch who shouted at the prying Milwaukee newsmen, “Come on, stop acting bush. Get off the bus,” the identity of the true culprit didn’t matter. What was said was said. The Yankees continued to reject the local hospitality as their train pulled into Milwaukee. Ignoring the local press and avoiding all of the city’s welcoming parties, the New Yorkers hurried onto a waiting bus and went directly to their hotel. Slighted, the local newsmen focused their stories on the festering “bush” incident and how they—and the entire city of Milwaukee—had been insulted. The Milwaukee Journal responded to the Yankees’ slur with an oversized headline that screamed, “Bushville!” “I’m not going to say [Stengel] woke us up, but he sort of inspired us. The publicity was embarrassing, like we were almost minor leaguers playing the Yankees,” Frank Torre remembered.

During the Yankees’ introductions before Game Three, Milwaukee County Stadium’s 45,804 fans booed mercilessly. The main target of their verbal abuse from the moment he stepped onto the field was Casey Stengel. Hardly offended by the reception, the Yankees manager gallantly blew a kiss into the stands.

Following the opening ceremony hostilities, Braves starter Bob Buhl gave up a gopher ball to the Yankees’ Tony Kubek in the top of the first. After walking Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra, Buhl made an errant throw into center field as he tried to pick off Mantle. “Mantle goes to third but we still got Berra going into second. We would have got out of that inning with just one run if the umpire had given us that out,” Haney complained to reporters following the game. Instead of two outs and a man on third, it was runners on second and third with just one out. When Mantle scored from third on a Gil McDougald sacrifice fly, Haney had seen enough. After only two-thirds of an inning, he pulled Buhl in favor of rookie Juan Pizarro.

In the second inning the Braves threatened to run Yankees starter Bob Turley out of the game after they scored a run and loaded the bases. But Stengel went to his bullpen and called upon Don Larsen. Making his first World Series appearance since pitching a perfect game in the 1956 Series, Larsen proceeded to scatter just five Milwaukee hits in seven and one-third innings of relief. Meanwhile, New York’s rookie shortstop Tony Kubek almost single-handedly outhit the Braves’ entire lineup. By knocking in four runs with three hits, including two homers, Kubek and the Yankees assaulted Milwaukee’s bullpen en route to a 12–3 thrashing. “It sobered the Milwaukee fans some,” Henry Aaron conceded. “Worst thing about it is, we’re in our own ballpark, but the Yankees have taken us apart, humiliated us before our own people in the only game we’ve played there.”

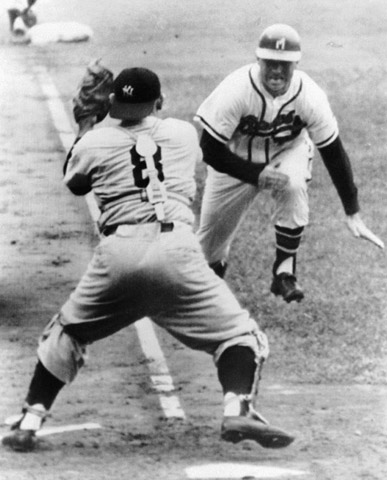

When Braves second baseman Red Schoendienst (4) tried to field pitcher Bob Buhl’s pickoff toss in Game Three, the ball went into center field, and the Yankees’ Mickey Mantle (7) raced to third on the error. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

With the demoralizing loss, the Braves were under tremendous pressure to rebound. In front of another capacity County Stadium crowd for Game Four, Warren Spahn tossed a steady stream of groundouts for eight innings. Meanwhile, the Braves built a comfortable 4–1 lead behind an Aaron three-run homer and a Frank Torre solo shot. In the top of the ninth, the Braves were within one out of evening the Series at two when Spahn unraveled. Having given up eleventh-hour hits to Yogi Berra and Gil McDougald, Spahn held a 3–2 count on New York’s Elston Howard—and surrendered the game-tying home run into the left-field stands. A tomblike silence fell over County Stadium. “We could have folded then. I really believe that,” Aaron recalled. “You never saw a quieter dugout in your life when we came in from the field. We all looked as if we’d been watching a murder.”

The Yankees shut down the Braves bats in the bottom of the ninth. In the top of the tenth, outfielder Hank Bauer tripled to drive home Kubek. New York was only three outs away from a 5–4 victory, and Braves manager Fred Haney was facing another demoralizing defeat. To lead off the home half of the inning, Haney opted for reserve infielder Vernal “Nippy” Jones to pinch-hit for Spahn. “I don’t think there’s any doubt about what was the turning point in the 1957 World Series,” Aaron declared.

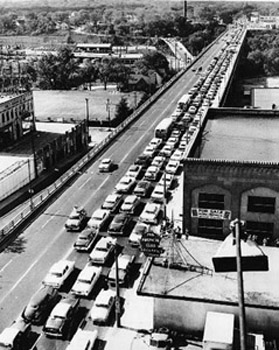

For over an hour before the start of Game Four, traffic clogged all three westbound lanes across the Wisconsin Avenue viaduct as fans filed into the County Stadium parking lot. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Although Jones had not played in the big leagues since 1952, the Braves had purchased his contract from Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League in July as first-base insurance. He was used sparingly during the 1957 season, appearing in just thirty regular-season games. But Nippy Jones’s first World Series appearance in a Milwaukee uniform would not be forgotten. Jones’s first pitch from Yankees reliever Tommy Byrne went wild. “The ball hit me on the foot and I dropped my bat and started toward first base,” Jones recounted. “But [umpire] Augie Donatelli said, ‘Come back here. That’s ball one.’ I couldn’t believe it.”

The County Stadium crowd of 45,804 couldn’t quite decipher the ruckus at home plate as Jones questioned the call. “Jones wasn’t the talkative sort. But he was talking now, and he was having it out with Donatelli chin to chin,” Aaron remembered.

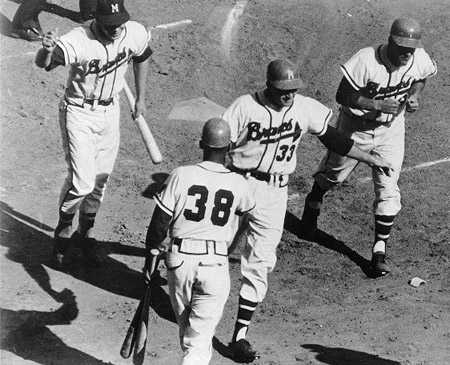

A Braves reception committee including Wes Covington (43), Eddie Mathews (41), and Johnny Logan (upper right) welcomed Henry Aaron (44) home after his three-run homer in the fourth inning gave Milwaukee an early lead. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

As Jones argued his case, the ball rolled back toward the plate after hitting the concrete backstop. “I went right for the ball,” Jones admitted, “and Yogi Berra was pretty smart, so he did the same thing. I got there first, and there was a spot of shoe polish about a half-inch in diameter [on the ball].”

When Donatelli saw the scuff mark, he awarded Jones first base. “Nippy was very meticulous about his uniform and how it looked, including his shoes. He insisted that the clubhouse boys polish his shoes before every game,” Eddie Mathews remembered. “Good thing he did. If that ball had hit my shoe, you wouldn’t have known it.”

Nippy Jones (25) was awarded first base after umpire Augie Donatelli showed Yankees catcher Yogi Berra (8) the shoe polish scuff mark on the ball. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Sensing a rally, Haney pulled Jones in favor of pinch runner Felix Mantilla. Red Schoendienst proceeded to sacrifice bunt Mantilla to second, allowing scrappy shortstop Johnny Logan to bat with the tying run in scoring position. Playing on an injured ankle that had to be drained before the game, Logan stepped to the plate with hopes of putting the ball into play: “All I could think of was base hit, base hit, base hit. I kept telling myself not to go for the long ball.” After waiting on the first two pitches, Logan slammed a clutch line drive into left field, bringing in Mantilla to tie the game at five. As the ball bounced into the left-field corner, the Braves shortstop entertained thoughts of heading toward third, “so Eddie could drive me in with a long fly, but I couldn’t take the gamble.”

Logan’s discretion left him at second when Mathews, who was 1-for-11 with the bat for the Series, stepped to the plate with one on and one out. “Before the game I had been thinking about Gil Hodges going 0-for-21 in the 1952 World Series,” Mathews confessed. “A Milwaukee sportswriter handed me three pennies and said, ‘Put these in your pocket for good luck.’ I wasn’t the slightest bit superstitious, but what the hell, I put them in my uniform pocket. I wasn’t hitting worth two cents, so maybe three would help.” Taking the count to 2–2, Mathews swung at a hip-high fastball. “I was worried for a second when I saw Hank Bauer in front of the right field fence, pounding his glove like he was going to make the catch,” he said. “I didn’t see the ball go into the seats, but the crowd reaction left no doubt that it was a home run.”

Eddie Mathews (41) was greeted at home plate after his tenth-inning home run evened the Series at two games apiece. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

The towering two-run blast broke Mathews’s slump and rejuvenated the entire Braves squad. “Ball game, 7–5, from death to life again.” Aaron exclaimed. “We knew we could win then, but not if it hadn’t been for Nippy Jones.”

When Nippy Jones returned to the dugout earlier in the inning, his box score statistics for Game Four consisted of a series of consecutive zeros—uncharacteristic stats for a World Series hero who had just made his last major-league appearance. “The importance of the event seemed to grow as time went on. The main thing to me was winning, and I didn’t care how we did it,” Jones remembered.

After Game Four Nippy Jones showed Braves equipment manager Joe Taylor the scuff mark left on the baseball from his polished shoes. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Game Five found the Yankees helpless against Burdette’s wicked sinker, as Whitey Ford simultaneously handcuffed the Braves’ bats. Both pitchers kept the game scoreless for five full innings, with Burdette’s shutout preserved by Wes Covington, whose wall-jumping, fence-crashing grab in the fourth inning kept a potential Gil McDougald home run out of the County Stadium stands. As the dueling aces battled into the sixth, Ford was almost out of the inning when Eddie Mathews stepped into the batter’s box. In what should have been the third out of the inning, Mathews bounced a high chopper toward the right side of the infield. Yankees second baseman Jerry Coleman fielded the ball cleanly but misjudged Mathews’s speed, and the Braves’ third baseman was safe at first. Aaron followed with a pop-up into short right, and Hank Bauer sprinted in as Coleman raced out to field the ball. As it dropped between them for a single, Mathews sped to third. Adcock slashed a single to bring Mathews home, giving the Braves a 1–0 lead. It was all Burdette needed, as he scattered just three more hits in the final three innings for a complete-game shutout. “When Lou needed to make a pitch, he did it,” Del Crandall said. “They didn’t hit many balls good off him. He was in and out, up and down … a little of this and a little of that. He just made great pitches. The Yankees couldn’t get comfortable looking for anything because he had everything working with just enough movement to keep it off the center of their bats. His location was outstanding.” With the 1–0 victory, Milwaukee held a three-games-to-two advantage as the World Series returned to New York.

The Yankees returned home to the “House That Ruth Built” with no intention of folding in Game Six. Once again, New York pounced on Braves starter Bob Buhl, and he failed to make it out of the third inning. Facing a two-run deficit, the Braves’ starting first baseman Frank Torre stepped to the plate to lead off the fifth inning. Playing in Yankee Stadium was something of a homecoming for the Brooklyn native. With dozens of his family and friends among the 61,408 fans in the stands, Torre cranked a home run off Yankees starter Bob Turley to cut New York’s lead in half. “I don’t even remember running around the bases,” Torre said. “It was a tremendous thrill, especially with my mother and one of my sisters at the game.”

In the top of the seventh, Aaron clobbered a solo homer to tie the game at two. Then, in the bottom half of the inning, the Yankees got to reliever Ernie Johnson as Hank Bauer connected for a solo home run off the left-field foul pole. Trailing 3–2, the Braves began a rally in the ninth, but after Mathews walked, Covington grounded into the game-ending double play, forcing the deciding Game Seven. After six weeks of spring training, 154 regular-season games, and six World Series contests, baseball’s 1957 world champion wouldn’t be decided until the season’s last possible day.

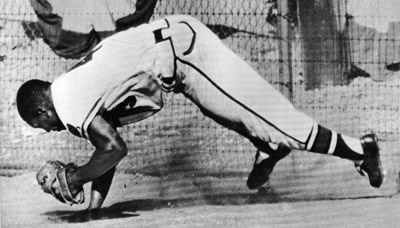

Wes Covington hung onto the ball after his leaping catch in left field near the 355-foot sign nabbed a long blow from Gil McDougald in the fourth inning of Game Five. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

During Game Five Lou Burdette threw only eighty-seven pitches against the Yankees and allowed just two fly balls to the outfield. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Braves catcher Del Rice tagged out the Yankees’ Yogi Berra at home plate on a throw from left fielder Wes Covington at the top of the ninth. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Fred Haney (left), Del Rice (7), Taylor Phillips (in jacket), and other ecstatic players greeted catcher Del Crandall (1) after his eighth-inning home run gave Milwaukee a commanding 5–0 lead in the Series-deciding seventh game. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

In 1957 the New York Yankees had been shut out only twice during their entire 154-game regular season. But Lou Burdette shut them out twice within four days and beat them three times to earn the World Series’ Most Valuable Player award. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

The victorious Braves hugged one another on the mound. Later they would cash World Series checks of $8,924.36 each. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

For Game Seven, 61,207 anxious fans filled Yankee Stadium on October 10 with hopes that Don Larsen would duplicate his World Series perfect-game performance 367 days earlier against the Dodgers. He was scheduled to face Warren Spahn, but after suffering a severe bout of the flu, Milwaukee’s ace was forced to bow out of the start and become a spectator in the Braves’ dugout. “I’m never nervous when I’m pitching. I’m more nervous watching somebody else pitch,” Spahn told the press. “Take a look at the bench during a World Series game and you’ll see what I mean. The players are biting their fingernails; they can’t sit still. Some of them stand on the top step and holler. It helps. I holler a lot from the bench.”

Spahn’s ailment forced Fred Haney to make the toughest decision of his managerial career: turn to one of his rested starters—Gene Conley, Bob Trowbridge, Juan Pizarro—or gamble on the stamina of Lou Burdette’s arm by starting him on only two days’ rest. The Braves manager followed his instincts. “When Fred told me he needed me to pitch, there wasn’t any way I was going to say no,” Burdette remembered. “I once relieved in 16 games out of 22. I’m bigger, stronger and dumber now.”

Burdette and Larsen pitched two scoreless innings before the Braves’ bats exploded in the top of the third. Following a Series-long slump, Bob Hazle started the scoring threat by singling to left with one out. Johnny Logan followed with a sharp liner that Tony Kubek misplayed, keeping everybody safe. When Mathews blasted a Larsen fastball into the right-field corner, Hazle and Logan scored. By the time Larsen was bounced after two and one-third innings, Milwaukee had scored four runs. Burdette fought his fatigue and actually seemed to gather strength as the game entered the later innings. “They would shake their heads and look up in the sky and wonder how someone could do something like that to them,” Del Crandall remembered. “They couldn’t believe anyone could get them out like that, and I think Lou fed off that. I could see their reaction very clearly from my position. That made it doubly satisfying to Lou and the rest of us.”

In the eighth, Crandall extended Milwaukee’s lead to 5–0 with a solo homer. In the bottom half of the inning with two outs, the Yankees mounted one final rally. With New York’s Gil McDougald on first base, Jerry Coleman singled to right. Tommy Byrne followed with a single to load the bases. As the tying run stood on deck, Moose Skowron sent a screaming grounder down the third-base line. Mathews backhanded the sharp smash and stepped on third base to force out Coleman for the Series’ final out. “I’d made better plays, but that big one in the spotlight stamped me the way I wanted to be remembered,” Mathews recalled. “A second later I was hugging Burdette and Crandall. Pretty soon everybody was hugging everybody.”

The Braves had won—despite their anemic .209 batting average, the lowest in history for a seven-game Series winner. “The Braves weren’t destined to win the [1957] Series with their bats,” Donald Davidson said, “but, as they say, pitching is 80 percent of the game, and we had Lou Burdette.”

Crowned as the World Series Most Valuable Player, Burdette became the first pitcher in thirty-seven years to win three complete games in a single Series—and held the Yankees scoreless for twenty-four straight innings. Not since Christy Mathewson pitched three shutouts in 1905 had a pitcher so completely dominated another team in a World Series. “I never heard of such a thing—pitching three complete game victories in one week,” observed Gene Conley. “And he did it against one of the greatest teams ever.”

His performance gained the attention and respect of his former manager, Casey Stengel, who told reporters after the final game, “Burdette was the big man of the Series. He took care of us all the way. He was just as good in the third game as he was in the second and as he was in the first. He made us hit the ball on the ground in nearly every tight spot. He was great.”

Although Burdette’s mastery on the mound stole the spotlight, Henry Aaron rocked the Yankees’ pitching staff with a .393 average. Going 11-for-28 with a triple, three home runs, seven RBIs, and a .786 slugging percentage, he was just as dominant at the plate as Burdette was from the pitching rubber. The Braves world championship was the culmination of a team effort. “The 1957 Braves worked harder and played harder than any group I’ve known. They had togetherness, they had talent—and they had fun,” Davidson affirmed.

Wisconsin native Andy Pafko, who had come home to finish his big-league career with the Braves, vividly remembered walking off the Yankee Stadium diamond that afternoon. “I considered myself the luckiest guy in the world,” he said in a 2006 interview. “I mean, what an opportunity to win a World Series championship for your home state. How lucky can one guy get?”

An estimated 400,000 fans packed the streets to celebrate Milwaukee’s 1957 World Series victory over the New York Yankees. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Throughout the 1957 World Series, Milwaukee’s downtown streets and stores were covered with banners and signs wishing the team good luck. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Back in Milwaukee, hundreds of thousands of fans jammed the streets as the city erupted. “From what I understand, the celebration in Milwaukee started as soon as I stepped on third base for the final out,” Eddie Mathews said. “They closed some of the bars and took the beer kegs right out onto the street.”

It was as if the victory cured the city of an inferiority complex. Mayor Frank Zeidler proclaimed Milwaukee “the baseball capital of the world.” The celebration rivaled the night in the midst of the Great Depression when Prohibition ended and beer was legal again. An estimated 100,000 jammed Billy Mitchell Airport, and the team’s victory parade downtown was delayed more than two hours because of the crowd. “It was the biggest crowd in the city’s history,” Milwaukee police chief Howard O. Johnson announced to reporters. “It was two or three times the size of the V-J Day crowd.”

While horns blared and factory whistles blew, 400,000 fans crowded the streets, forcing city officials to alter the original parade route. “Wisconsin Avenue was solid people,” Eddie Mathews recalled. “All along the way we saw hand-lettered signs: ‘Burdette for President,’ ‘Mathews for Vice President,’ ‘Spahn for Mayor,’ and ‘We love you, Bush Leaguers.’ ” The five-mile-long victory parade concluded inside a packed County Stadium. “The problem was, now we were trapped. We had to get a police escort, one at a time, to get our cars parked outside. It was a night to remember—although I don’t remember most of it.”

An enthusiastic Milwaukee Braves fan placed a World Series sign at the corner of Fifth and Wisconsin Avenues. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Once the World Series celebrations subsided, the Braves began collecting numerous postseason awards and accolades. Aaron was named the National League MVP, and Warren Spahn clinched the Cy Young Award just one vote short of unanimously. Burdette earned several awards, including Sport magazine’s “Man of the Year.” The annual Associated Press All–Major League club selected five Braves—Burdette, Spahn, Mathews, Schoendienst, and Aaron—to the first team and voted Fred Haney National League Manager of the Year. “All of those things made 1957 the best year of my baseball life, and it went along with the best year of baseball that any city ever had. It doesn’t get any better than Milwaukee in 1957,” Aaron declared.

While the 1957 Milwaukee Braves were considered one of the scrappiest, grittiest, and most determined teams to ever participate in the Fall Classic, little did anyone anticipate how their kingdom was about to crumble, especially Aaron: “I didn’t realize it at the time, but after we won the seventh game of the World Series in 1957, everything started to go downhill.”

♦ ♦ ♦

America’s Pastime was in the throes of an economic revolution by 1958. As baseball’s landscape continued to shift west, the Braves’ success in Milwaukee was often credited as its catalyst. “I said when we moved to Milwaukee,” Braves’ owner Lou Perini commented at the time, “and I say it now—there will be sweeping changes in the baseball map. Since we came to Milwaukee, Baltimore and Kansas City have come to the majors.” Perini called the trend a new era of “baseball-community partnership”: “The day of the individual owner building a baseball plant has ended. It is no longer economically possible.”

Further proof of Perini’s theory occurred when two of baseball’s marquee franchises announced plans to abandon New York for the West Coast. Unable to persuade civic leaders to help build new ballparks, owners Walter O’Malley of the Dodgers and Horace Stoneham of the Giants transferred their franchises to Los Angeles and San Francisco prior to the start of the 1958 season. Enticed by the promise of money, civically funded stadiums, ample parking, and no longer having to share fan bases with cross-town rivals, their simultaneous move represented a recalibrated approach to the game: profits over civic loyalty. “It’s just impossible to operate with parking facilities for only 700 cars while Milwaukee, for instance, parks 18,000,” O’Malley told reporters. “The park [Ebbets Field] is old-fashioned, antiquated, unsuitable. We just can’t compete with the other ball parks, nor with the race tracks.”

Inspired by the Braves’ success in Milwaukee, the Dodgers and the Giants relocated west before the start of the 1958 season. (COURTESY MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, FRANK J. MARASCO CARTOON COLLECTION)

The United States Congress held hearings in 1958 to discuss the sport’s sudden carpetbagger approach. Baseball commissioner Ford Frick justified the Dodgers’ and Giants’ relocations: “There is demand for Major League Baseball around the country. Now when two clubs or three clubs are in a town and one of them moves, it still leaves that town with baseball. As commissioner of baseball, I think that is good, because you are taking baseball to a new community without leaving the old town barren. However, when the time comes that you start moving a club from a one-club city to another one-club city merely for the sake of moving, then the commissioner is very definitely opposed.”

During spring training in Bradenton, the Braves were hounded by sportswriters looking to get quotes and fans seeking autographs. “I’ve got a face you can’t forget, and I usually get nailed as soon as I set foot outside,” Warren Spahn confessed. Along with their newfound national appeal, the Braves were considered heavy favorites to repeat as World Series champions, with a roster almost identical to their 1957 squad. “It appeared that John Quinn had built a dynasty,” Donald Davidson said.

The Milwaukee Braves officially began their defense of the world championship on April 15 during the home opener against the Pirates. After the ballclub’s ceremonial raising of the pennant atop County Stadium, Warren Spahn pitched nine strong innings and Eddie Mathews belted two homers. But in the fourteenth inning Gene Conley gave up a run, and the Braves lost 4–3, their first home opener loss since moving to Milwaukee. The team quickly made amends, winning their next three contests behind fine pitching performances from Burdette and Buhl and a shutout by Spahn. Milwaukee’s typical slow start left them with a respectable 8–5 record and a half game behind the first-place Giants by the end of April.

The Braves raised their 1957 world championship pennant above County Stadium before the start of the Opening Day game in 1958. (COURTESY OF MIKE RODELL)

Warren Spahn and Henry Aaron received their respective 1957 Cy Young and MVP awards at County Stadium. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Red Schoendienst and Joe Adcock dressed in team-issued blazers during a Braves road trip. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

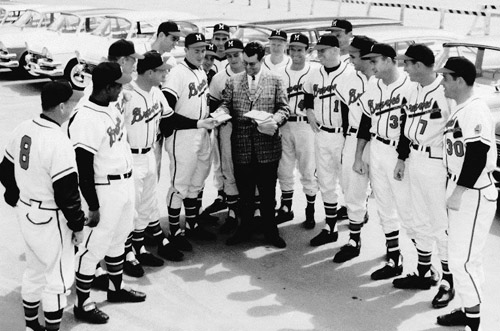

Local car dealer Wally Rank (wearing suit) annually handed out keys for brand-new cars to every Braves player, stars and benchwarmers alike. (COURTESY OF MIKE RODELL)

As reigning kings of the National League, Fred Haney’s crew was tested early and often. The Braves’ manager was forced to juggle lineups due to nagging injuries and disappointing performances. “All year the outfield was a matter of ‘Who can play today?’ One day Haney had seven infielders in the starting lineup, with Adcock, Mantilla and Harry Hanebrink playing outfield,” third baseman Eddie Mathews explained.

Still mending from his collision with Felix Mantilla the previous season, Billy Bruton didn’t begin patrolling center field until May 24. Wes Covington’s knee injury during spring training would limit him to just 90 games over the course of the 154-game regular season. The Braves’ surprise spark of ’57, Bob “Hurricane” Hazle, was sold to Detroit after starting the 1958 season hitting a frigid .179. According to Eddie Mathews, “The other ballplayers were completely stunned and upset about it. Here was a guy who came out of nowhere and led us, not single-handedly, but led us to our first World Series. He was in a slump for the first month of 1958, but he’d had some ankle trouble in spring. We figured the ball club owed him more than that.”

Bob Buhl’s numerous arm ailments sidelined him in May after he started the season hot with three straight victories. Second baseman Red Schoendienst was limited to just 106 games as he suffered through bruised ribs, a broken finger, and pleurisy in 1958. But it was a series of inexplicable symptoms that truly affected his play. “I wasn’t feeling that good. I was really run down. I knew something was wrong, and I knew it wasn’t just a cold,” Schoendienst remembered.

The injuries had crippled the Braves potent lineup and dependable pitching staff; nevertheless, the Braves spent most of the season’s first half bobbing in and out of first place. Although Milwaukee stood atop the National League standings alongside the Giants, who had found early-season success in their new San Francisco surroundings, manager Fred Haney felt his talented team should have been dominating the competition.

When the Braves arrived in California for their inaugural West Coast road trip, Haney harped on his squad for being too comfortable and lacking focus. “It’s a funny thing,” the Braves’ skipper surmised, “but a manager can’t get a player to listen to him the way another player can. Coming from a manager, it’s critical. Coming from a player, it’s constructive.”

Desperate to motivate his players, Haney began to invite his celebrity friends from his days as manager of the Hollywood Stars minor-league team into the clubhouse. “Fred was Mr. Hollywood,” Eddie Mathews said. “He knew everybody out there. He liked to bring in movie stars to talk to us, I guess to impress us. One time he brought Pat O’Brien into the clubhouse to give us the Gipper speech from The Knute Rockne Story.”

Manager Fred Haney was hung in effigy after the Braves lost their fifth straight game on July 5, 1958. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

But the Braves couldn’t seem to pull away from the pack in what became one of the tightest pennant races in recent years, with no team trailing first place by more than nine and a half games in June. Although they held a one-and-a-half-game lead over the Giants, the Braves had dropped eleven of twenty games during a three-week home stand. Milwaukeeans accustomed to winning were becoming disenchanted. On July 5 several hostile fans hung an effigy of manager Fred Haney from a construction crane at a downtown Milwaukee demolition site. “I think in 1957 the country wanted us to win the pennant and beat the Yankees. In 1958 I think they expected it.” Mathews said.

Escaping the growing resentment in Milwaukee, Haney and the Braves’ All-Star representatives—Henry Aaron, Del Crandall, Johnny Logan, Eddie Mathews, Don McMahon, and Warren Spahn—gathered in Baltimore on July 8 for the 1958 All-Star Game. The American League won 4–3 in a game that didn’t feature an extra-base hit by either club.

Milwaukee ended its five-game losing streak on July 6 by shutting out the Pittsburgh Pirates 2–0 behind the pitching of Joey Jay (left) and Wes Covington (right), who homered in the seventh inning. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

After the All-Star break, the Braves continued to fail in their attempts to extend their first-place lead. They dropped their West Coast opener in Los Angeles and struggled in San Francisco. After salvaging a sweep of the Cardinals in St. Louis and taking two of three from the Cubs in Chicago, the Braves returned to County Stadium on July 30 to begin a nineteen-game home stand.

With the opportunity to take sole possession of first place, Milwaukee sent Warren Spahn to the mound to face Los Angeles’ Sandy Koufax. Seeking his first victory over the Dodgers in seven years, Spahn stayed on even terms with Koufax for seven innings. In Milwaukee’s half of the eighth, with the game tied at three, Koufax served up Eddie Mathews’s twenty-first home run of the season to secure the Braves’ 4–3 victory. Spahn’s jinx had been lifted as he beat the Dodgers for the first time since September 25, 1951.

The Braves entered August with a slim one-and-a-half-game lead over San Francisco, who arrived at County Stadium on August 1 for a crucial four-game series. Milwaukee polished them off in a four-game sweep en route to winning seventeen of twenty-two games. “The one thing that really held us up during the 1958 season was the pitching,” Henry Aaron recalled.

Without the services of star hurlers Bob Buhl and Gene Conley due to arm ailments, Carlton Willey, Joey Jay, Juan Pizarro, and Bob Rush performed magnificently for the Braves all year. Led by Spahn and Burdette, the club’s revamped pitching corps all but vanquished the rest of the National League during the second half of the season. During a crucial mid-August series in Philadelphia, Braves pitchers smothered the Phillies in a four-game sweep. Willey threw a shutout in the first game, 1–0. Spahn took the second game 2–1, followed by Juan Pizarro and Lou Burdette winning both ends of a doubleheader, 5–1 and 4–1. During the month of August, Spahn had won four games, Willey five, and Burdette seven as Milwaukee extended its first-place lead to eight games over the fading Pirates and Giants. Nobody appreciated the young hurlers’ efforts more than manager Fred Haney. “They sure came through for me,” he told reporters. “Barring injuries, they should be winning for a long time.”

Carlton Willey hurled a shutout in his first big-league start, finished the season with a 2.70 ERA, and was selected by the Sporting News as its 1958 National League Rookie of the Year. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

On September 21 in Cincinnati, with the chance to clinch their second consecutive National League pennant hanging in the balance, the Braves turned to Warren Spahn. With a four-run fifth inning followed by a two-run homer from Aaron in the seventh, Milwaukee slugged its way to a 6–5 win, giving Spahn his twenty-first victory of the year. The Braves had secured their second consecutive National League pennant and held an impromptu celebration in the clubhouse after the game. “We won the pennant by eight games that year—the same margin we won by in 1957—but somehow there wasn’t quite the atmosphere that we’d enjoyed the season before,” Aaron recalled. “Maybe it was just that we expected the same magic all over again and that was impossible, because 1957 was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

The Braves won four of their final six games to finish with a 92–62 record, winning the pennant with three fewer victories than the prior season. While many teams had suffered drops in attendance following world championship seasons, Milwaukee had always run contrary to conventional baseball attendance trends. But after pulling in a record 2.2 million in 1957, Milwaukee County Stadium recorded only 1.97 million fans through its turnstiles in 1958. This slight but unmistakable decrease in attendance left Eddie Mathews to conclude, “Declining attendance said the Braves’ product had lost some of its zest.”

Also suffering a surprising drop in attendance were the Yankees, who with the departure of the Dodgers and Giants had become New York’s sole baseball occupants in 1958. Winning ninety-two games and outdistancing the second-place White Sox by ten games, the Yankees were ready for their rematch with the Braves. “The Yankees didn’t have much trouble getting to the World Series again, either. The two of us were far and away the class of our leagues, and we knew that if we could beat them twice in a row we would clearly establish ourselves as the best team in baseball,” Aaron said.

Because the Braves were returning to the World Series as the reigning champs, they were no longer perceived as underdogs. “Whatever you do, don’t get overconfident,” Haney warned his players. “Maybe it looked easy, but it wasn’t. And don’t forget, we’ve still got a World Series to play.”

♦ ♦ ♦

The 1958 World Series opened in Milwaukee with County Stadium filled to the rafters. Game One on October 1 featured the rematch of mound masters Whitey Ford and Warren Spahn. The Yankees grabbed an early lead on a Moose Skowron homer. The Braves battled back in the bottom half of the inning with a string of three singles by Crandall, Pafko, and Spahn. The Braves went ahead 2–1, but the lead lasted only into the top of the next inning. After Spahn walked Ford, Hank Bauer crushed a hanging screwball into the bleachers for a 3–2 New York lead.

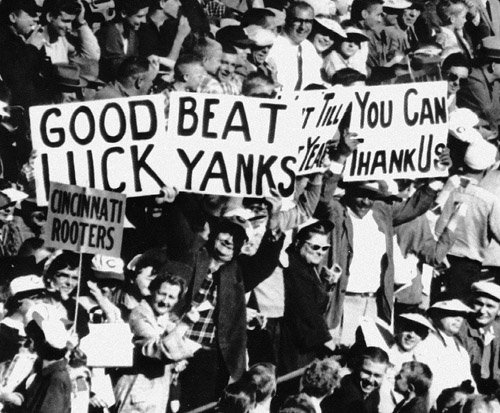

Cincinnati Redlegs fans wished the Braves good luck in their upcoming World Series rematch against the Yankees. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

The 1958 World Series–bound Braves were again led by (from top left) Warren Spahn, Frank Torre, Henry Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Red Schoendienst, Johnny Logan, manager Fred Haney, Del Rice, Ernie Johnson, Wes Covington, Del Crandall, Joe Adcock, and Lou Burdette. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

A pep rally was held in front of Milwaukee’s Schroeder Hotel before the start of the 1958 World Series. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Eddie Mathews took deliberate aim in bunting during a pre–World Series practice. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Milwaukee tied it up in the home half of the eighth. Meanwhile, Spahn kept the Yankees bats quiet, scattering just seven hits through nine innings. In the decisive tenth inning, the Braves strung together three singles by Adcock, Crandall, and Bruton, who drove in Adcock with the winning run. With the 4–3 victory, Milwaukee captured the early 1–0 Series lead. “If you can win that first Series game, you’re really floating along on clouds,” Spahn asserted. “Your confidence in yourself and your team gets a tremendous boost, especially when you figure it takes only .500 ball to win at that point.”

For Game Two, 46,367 Milwaukee fans watched the Yankees load the bases in the top of the first inning. “Tension was thick in Game Two because Lou Burdette, boasting 24 straight scoreless innings, needed only six more zips to break Babe Ruth’s World Series pitching mark,” Donald Davidson said.

The Yankees scored an unearned run in the first inning, ending Burdette’s bid to break Ruth’s series record of twenty-nine and two-thirds shutout innings. As New York took an early 1–0 lead into the bottom half of the frame, the Braves initiated the greatest first-inning bombardment in Series history. Led off by a home run by Billy Bruton and bookended with a three-run blast by Burdette, Milwaukee erupted for seven runs. With the early lead, Burdette coasted behind Milwaukee’s fifteen-hit attack for the 13–5 win. Having tomahawked the Yankees during both games at County Stadium, the Braves were only two victories away from once again devastating baseball’s most dominating team. “When we caught the plane to New York that night, most of us were thinking that the World Series was over and that we were the greatest baseball team known to man,” Aaron remembered.

The story for Game Three in New York was Yankees starter Don Larsen, who silenced the Braves bats. Milwaukee’s Bob Rush kept pace for the first four innings but walked the bases full with two outs in the fifth. As the Yankee Stadium crowd roared in the background, Bronx Bomber Hank Bauer came through with a single that scored two. In the seventh, Braves’ reliever Don McMahon was unable to contain Bauer’s hot postseason bat and surrendered a two-run home run to give the Yankees a commanding 4–0 lead. Although Yankees reliever Ryne Duren was a bit wild during the last two innings, Milwaukee became the victim of a six-hit shutout.

Lou Burdette (33) was congratulated by Billy Bruton (38) after hitting a three-run home run to extend the Braves’ early 7–1 first-inning lead in Game Two. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Game Four featured the Braves’ Warren Spahn once again facing Whitey Ford. The game remained scoreless until New York started to unravel in the top of the sixth. Facing into a fierce sun, Yankees’ left fielder Norm Siebern misplayed a simple pop-up off the bat of Red Schoendienst that went for a triple. When Tony Kubek erred on a Johnny Logan grounder, Schoendienst scampered home for the game’s first run. In the seventh, Siebern suffered another unforgivable defensive lapse. After he got a late jump on a soft, sinking flare to shallow left field, the ball fell in front of him and Crandall scored the Braves’ third run of the game. With the comfortable lead, Spahn became untouchable and even managed to halt Hank Bauer’s seventeen-game World Series hitting streak. Throwing 112 pitches while surrendering only two hits in the 3–0 victory, Spahn gave the Braves what appeared to be an insurmountable three-games-to-one Series lead. “Now there was no question about it,” Aaron recalled, “it was just a matter of time. We were the greatest and we all knew it, but we didn’t go around talking about it. It might have been better if somebody had popped off a little about how great we were. Then somebody could have shut them up, and we would have all been reminded that humility is something that even great teams have—even teams as great as the Milwaukee Braves of 1958.”

Center fielder Billy Bruton was the man of the hour after his single in the tenth inning of Game One won the game for the Braves. He went on to have a great 1958 Series, connecting for seven hits and a .412 batting average. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Helping to give Milwaukee a commanding three-games-to-one Series lead, Red Schoendienst (left) connected for a triple in the sixth inning of Game Four and scored the Braves’ first run, while his fielding helped preserve Warren Spahn’s (right) two-hit shutout. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Just nine innings away from their second consecutive world championship, the Braves sent Yankee-slayer Lou Burdette to the mound for Game Five. After Gil McDougald homered in the third to give the Yankees an early 1–0 lead, the New York sun began casting some menacing shadows onto the Yankee Stadium diamond. “We found out the hard way that the Yankees, for example, are a team you’ve got to keep under your thumb every minute if you expect to beat them in a big game,” Spahn remembered.

Looking to mount a rally in the top of the sixth, Billy Bruton led off with a single. Red Schoendienst followed with a liner into left with hopes of advancing the speedster. Yankees left fielder Elston Howard fought the glare and dove to his knees while sticking out his glove to make a circus catch. Caught off first, Bruton was doubled up. All of a sudden Milwaukee had nobody on and two outs. It may have been the turning point in the Series. The Yankees finally figured out Burdette in their half of the sixth and smashed their Series nemesis for six runs. Behind Bob Turley’s powerful ten-strikeout, five-hit shutout, the Yankees pulled to within a game of tying the Series with the 7–0 victory.

Following the flogging, doubt began to plague the Braves players as they returned to Milwaukee for Games Six and Seven. “You could tell on the plane that we weren’t quite sure we were as great as we had thought we were the day before,” Aaron revealed.

Milwaukee hoped Warren Spahn could deliver the decisive knockout punch in Game Six at County Stadium. Although Haney’s doubters felt the Braves manager was asking too much of his thirty-seven-year-old ace by pitching him on limited rest, Spahn had already won two games in the Series and was trying to win his third to duplicate Burdette’s feat from the year before.

In the top of the first, New York’s Hank Bauer powered his fourth Series home run into the left-field bleachers, but the Braves responded by touching up Yankees starter Whitey Ford to tie the score at one after one. Pitching on just two days’ rest, Ford was pulled in the second inning after the Braves took a 2–1 lead on singles by Covington, Pafko, and Spahn. When Schoendienst walked to load the bases, Art Ditmar took the hill for the Yankees to face Johnny Logan. The Braves’ shortstop hit a short fly ball into left field. As Elston Howard made the catch, Pafko tagged up at third but was nailed at the plate with a rocket throw.

The Yankees tied the score in the sixth, and the game stayed deadlocked at 2 through regulation. In the top of the tenth, Gil McDougald connected for a home run off Spahn to break the tie. With two outs, Howard and Yogi Berra singled, prompting Haney to call for reliever Don McMahon. But he didn’t quiet the Yankees bats, and Moose Skowron smacked a single to score a vital insurance run. In need of two runs, the Braves hitters were more than capable of making up the deficit.

A headfirst slide by Andy Pafko (right) in the second inning of Game Six wasn’t enough to avoid the tag from Yankees catcher Yogi Berra (left). (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Automobiles filled the County Stadium parking lot before Game Seven of the 1958 Series. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Determined to finish the Series in six games, the Braves’ Red Schoendienst led off the home half of the tenth inning with a grounder to second base. The usually sure-handed Gil McDougald fumbled the ball as the crowd roared in anticipation of a rally. But the second baseman quickly recovered and managed to throw Schoendienst out. Johnny Logan worked a walk off the Yankees’ bespectacled smoke-ball artist Ryne Duren, keeping the Braves’ hopes for a rally alive. After Eddie Mathews struck out, Aaron singled. Joe Adcock followed with another single that drove Logan home to narrow the gap to 4–3. But Bob Turley came on in relief for the Yankees and retired Frank Torre on a lineout to second base. With the ten-inning, 4–3 triumph, New York had tied the Series at three games apiece. But the Braves were still confident they could repeat as world champions. “We thought we could beat them before the first game, and we still thought we could beat them before the last one,” Spahn insisted.

As Game Seven’s 1:00 p.m. start time approached, the Milwaukee crowd of 46,367 shuffled into County Stadium with guarded optimism. Although Lou Burdette was pitching, they were all too aware that a loss would make the Braves the first club since the 1925 Washington Senators to lose the Series after being up three games to one.

After Burdette pitched a perfect top half of the first inning, the Braves looked to rout Yankees starter Don Larsen—just as they had done in the third inning of 1957’s Game Seven. Red Schoendienst opened the bottom half with a single, followed by a Billy Bruton walk. Frank Torre then sacrificed the runners to second and third. Immediately going into ninth-inning strategy, Yankees’ manager Casey Stengel ordered Aaron intentionally walked to load the bases. Wes Covington followed by grounding out to first, allowing Schoendienst to score the game’s vital first run. As Bruton stood on third and Aaron at second, Stengel ordered Eddie Mathews intentionally walked. With the bases loaded and the opportunity to break the game wide open, Del Crandall stepped to the plate. But he took a called third strike. The Yankees had avoided disaster and now trailed by just one run.

To lead off the Yankees’ second inning, Burdette walked Yogi Berra. Elston Howard followed with a sacrifice bunt toward first baseman Frank Torre. As Burdette ran to cover first, Torre’s throw was behind him and bounced off his glove. With everybody safe, the Yankees had runners on first and third with no outs. Jerry Lumpe hit a grounder to Torre, who held Berra at third but again made a throw that Burdette couldn’t handle. Charged with his second throwing error, Torre was frustrated. “I don’t think I deserved the errors,” he disclosed to reporters after the game, “but if you want to have a goat, it might as well be me.”

With the bases loaded, Moose Skowron hit into a force play at second to score Berra. After Milwaukee native Tony Kubek drove in the Yankees’ second run with a sacrifice fly, the Braves had also avoided a disaster. Despite the bad inning and a 2–1 deficit, the Braves seemed ready to take command in the third when Bruton led off with a single. After Larsen gave up another single to Aaron with one out, Casey Stengel made what many considered the key move of the game. Looking to extinguish another Braves rally, he called for hard-throwing right-hander Bob Turley. All Turley had done in the previous three days was pitch a five-hit shutout in the fifth game and get the final out in the Yankees’ Game Six victory. With one out and two runners on base, Turley got Covington to ground out. Stengel once again ordered Mathews walked intentionally. For the second time in three innings, Del Crandall stepped to the plate with the bases loaded. Once again he couldn’t capitalize and grounded out to second, ending the inning. In the sixth, Crandall redeemed himself with a solo home run to tie the game at two.

As the game went into the late innings, the tension at County Stadium continued to rise. For seven innings, Burdette and Turley had staged tremendous theater, with a plethora of ground balls and fast outs to keep the game close. In the eighth, Burdette retired the first two Yankees batters. Then Berra hit a drive off the right-field wall for a double. Elston Howard followed by smacking a bouncer up the middle, just beyond the reach of shortstop Johnny Logan. The hit scored Berra and gave the Yankees a 3–2 lead. Pinch hitter Andy Carey followed with a single off the glove of third baseman Eddie Mathews that left runners on first and third. “The Yanks will play for one run at a time, but they can break open a ball game with a big inning at any time,” Spahn declared.

Following his stellar 1957 World Series MVP per-formance, Lou Burdette finished the 1958 Series with a 1–2 record and 5.64 ERA. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Manager Fred Haney refused to go to his bullpen and allowed Burdette the opportunity to pitch out of the jam. Moose Skowron proceeded to crank Burdette’s usually unhittable changeup into the left-center stands for a devastating three-run homer. With one swing of his bat, Skowron had psychologically crushed the County Stadium crowd. The Braves trailed 6–2 with just six outs left in the 1958 World Series. What had been a frenzied Game Seven a half inning earlier became a slow death march. As the game drew to a close, the Braves attempted to muster one last rally in the bottom of the ninth. Mathews led off with a walk, but Crandall and Logan followed with fly-outs. Joe Adcock kept the Braves’ hopes alive with a single, but Schoendienst lined out to Mickey Mantle to end the Series. “There is a very narrow line between the team that wins the Series and the one that comes in second,” Spahn confessed. “We scored seventeen runs in the first two games, and 25 for the Series. That’s it in a nutshell.”

The New York Yankees celebrated on County Stadium’s infield after clinching Game Seven of the 1958 Series. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Eddie Mathews batted just .160 and struck out a record eleven times during the 1958 World Series. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

In a quiet Braves clubhouse the players tried to come to terms with their historic collapse. “We didn’t think we could lose two straight in Milwaukee. Maybe that’s why we did,” Aaron admitted.

Although Billy Bruton led series hitters with a .412 average, the Braves had struck out a record fifty-six times, with eleven of those strikeouts from Eddie Mathews, another record. “The turning point was in our bats. We got eight runs in [the last] five games… . Instead of moaning, let’s just say how good their pitching was,” Haney told reporters in the locker room after the game. With two victories and a save in the Yankees’ big comeback, Bob Turley was named the Series’ Most Valuable Player.

But even more disturbing than the Braves’ Series defeat was the malaise befalling the team and its city. After nearly six years of bliss, the sheen that Major League Baseball had brought to Milwaukee began to tarnish. The players, team officials, civic leaders, and once-devoted fans all knew that Braves baseball had lost its innocence. “It was the beginning of the end of an era in Milwaukee,” Donald Davidson concluded.