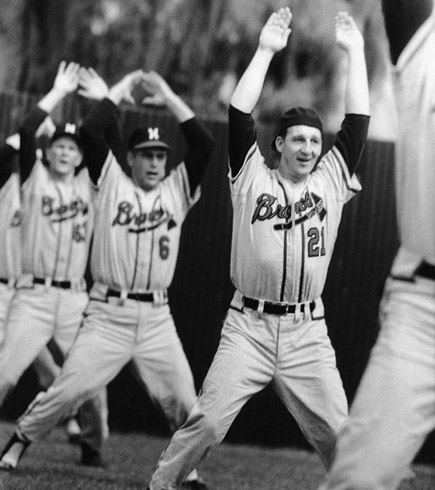

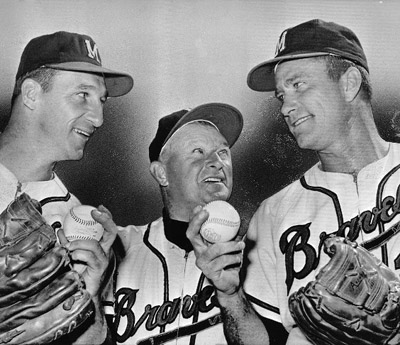

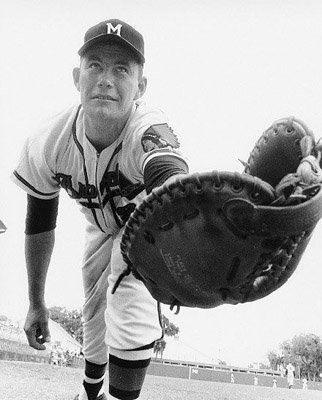

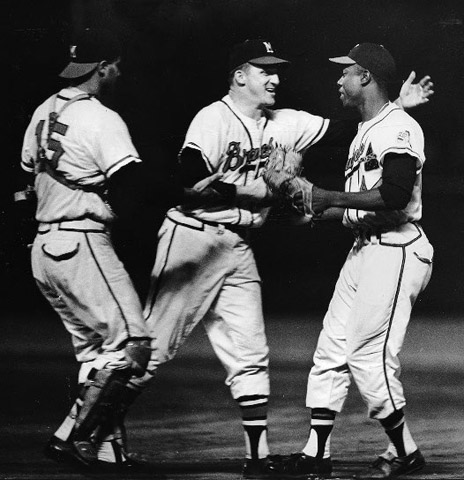

Warren Spahn (with cap on backward) kept his teammates relaxed with his continual banter and antics. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Despite the Braves’ 1958 World Series collapse, prognosticators picked them to win a third consecutive pennant in 1959. With a roster that had changed little from the previous two seasons, they looked as solid as ever. But ideological shifts within the organization suggested otherwise, the first being Lou Perini’s appointment of Birdie Tebbetts to the Braves front office.

Nicknamed Birdie for his high-pitched voice and talkative nature, George Robert Tebbetts spent fourteen years as an All-Star catcher with the Tigers and Red Sox before he was named the Redlegs’ manager in 1954. Tebbetts led Cincinnati to only one first-division finish before being fired late in the 1958 season with the team again in last place. “During Tebbetts’ managing tour with Cincinnati, the Braves and Redlegs developed quite a rivalry, which included several bean ball exchanges and brawls,” Braves historian Gary Caruso recounted in The Braves Encyclopedia. “The Braves’ decision to hire Tebbetts as executive vice-president in the fall of 1958 must have seemed rather curious to the Milwaukee players and fans.”

When Tebbetts exchanged his cap and jersey for a suit and tie, Braves general manager John Quinn was without a clear role within the organization. “Quinn had been a loyal employee of Lou Perini’s for many years, but Tebbetts was brought in basically as Quinn’s boss,” third baseman Eddie Mathews explained in his autobiography, Eddie Mathews and the National Pastime.

The architect who built the Braves into a National League powerhouse was no longer making the personnel decisions for Perini’s franchise. “I never could figure why John Quinn got bounced out of his job,” Henry Aaron noted in Aaron. “That’s what it amounted to, as far as I’m concerned.”

The Phillies lured Quinn to Philadelphia with a lucrative salary and the title of vice president. “Many people thought Perini made a big mistake letting Quinn go. He was a good baseball man,” Mathews said.

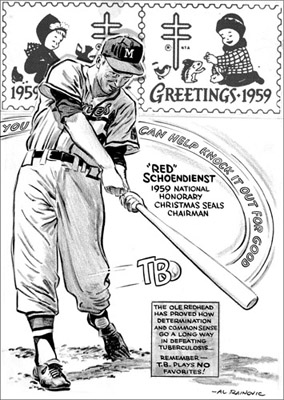

Diagnosed with tuberculosis shortly after the 1958 World Series, Red Schoendienst was visited in the hospital by (from left to right) Braves publicity director Donald Davidson, executive vice president Birdie Tebbetts, and general manager John Quinn. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

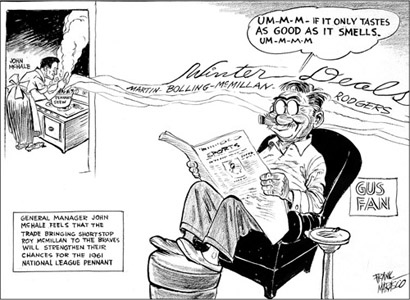

Taking over for Quinn as the Braves’ general manager was John McHale, recruited from the Tigers. After a brief playing career, McHale had quickly risen through Detroit’s front-office ranks and in 1957, at the age of thirty-five, became the youngest general manager in the game. He was expected to continue the Braves’ winning tradition with masterful trades and the nurturing of the team’s blossoming farm system.

Tebbetts’s and McHale’s arrivals and the abrupt departure of John Quinn left manager Fred Haney in a precarious situation. “You can imagine, I guess, what spring training was like, the players not knowing what to expect from Tebbetts or McHale, and wondering what was going on between Haney and Tebbetts,” Henry Aaron recalled. “And people told me that Haney and Tebbetts didn’t like each other at all.”

As former dueling National League managers—with neither too fond of the other’s managerial style—Haney and Tebbetts had a tension-filled history. Rumors began circulating that the only way that the Milwaukee skipper would survive past 1959 was to win—not just another National League pennant, but the World Series. The pressure on Haney mounted as the Braves lost nine of their first ten spring training exhibition games. “We were just going through the motions. We were all moving around like a bunch of King Farouks. We played like we were fat, rich and spoiled,” Aaron confessed.

Glaringly absent from the Braves’ spring training clubhouse was Red Schoendienst. After suffering through a season of deteriorating health, he had been diagnosed with tuberculosis following the 1958 World Series. “Leadership is hard to define,” Mathews explained. “Without him we had a real deficiency at second base. If Red had stayed healthy, I really believe we would have run away from the pack in 1959. He made that much of a difference.”

Another fan favorite missing from the Braves’ spring training dugout was the often-injured Gene Conley. Earlier that spring, John McHale had sent baseball’s tallest man to the Phillies because the Braves had an abundance of talented young arms—Joey Jay, Carl Willey, and Juan Pizarro—who were expected to join the established rotation of Spahn, Burdette, Buhl, and Bob Rush.

Back in Milwaukee, preseason ticket sales at County Stadium continued to stagger following the slight dip in 1958’s attendance. While the Braves’ attendance figures remained among the highest in the league, the team was no longer breaking records. Milwaukee’s fervor for Braves baseball had definitely diminished. Nevertheless, 42,081 Braves fans filled County Stadium on April 14 to see Don McMahon relieve Warren Spahn for the win in an extra-inning home opener against the Phillies.

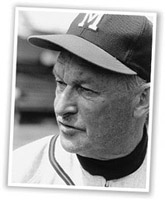

Red Schoendienst and his clubhouse leadership were sorely missed during the 1959 season. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 90)

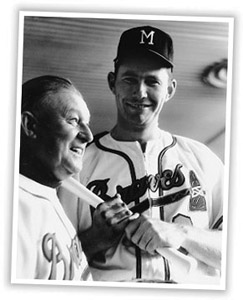

General manager John McHale traded in his Detroit Tigers skin for a Milwaukee Braves war bonnet in 1959. (COURTESY MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, FRANK J. MARASCO CARTOON COLLECTION)

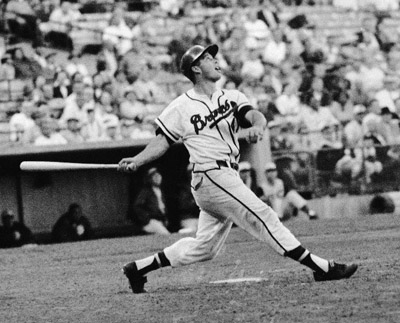

Milwaukee started the season hot by winning four straight and six of seven. Behind the blistering bats of Eddie Mathews and Henry Aaron, the Braves continued to play good ball into May. When Mathews connected for his fourteenth home run on May 19 to help beat the Cardinals, it put him thirteen games ahead of Babe Ruth’s pace to reach sixty home runs in a season. Meanwhile, Aaron was belting the ball at an impressive .468 clip, and it looked as if he’d reach the sacred mark of hitting .400 in a season, last achieved by Ted Williams in 1941. “With those wrists Henry is capable of hitting .400,” Fred Haney told reporters, “but don’t forget it takes luck as well as ability. The hits have to drop in all year long.”

Aaron’s luck continued as he hit near .500 well into the season. It seemed no scouting report could pin down his style at the plate. “I think the umpires liked me, because I made their job easy,” Aaron confessed. “I would swing at anything in the area code, and I never argued.” By midsummer Hammerin’ Hank commanded the pitchers’ utmost respect, if that can be gauged by how close opposing pitchers were throwing at his head. “I wasn’t hit that much,” he remembered. “But I got thrown at quite a bit. I hit behind [Eddie] Mathews, who was averaging 40 home runs a year. Back then, when a guy hit a home run, the next guy would go down.”

Although he continued to tear up National League pitching, Aaron was continually neglected by the press, while more dramatic playmakers such as Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, and Roberto Clemente were romanticized in national newspaper headlines. “It’s that loping gait of his,” Fred Haney explained. “He doesn’t look like he’s really hustling out there. Then you notice Hank always seems to get up to a fly ball when there’s any chance in the world of making the play.”

Never one for the spotlight, Aaron prided himself on being a complete ballplayer. “He was never a flashy player,” recalled Red Schoendienst. “He just went out and played his game. He picked up his bat and picked up his glove. He went over the lines and played with hardly any fanfare.”

Braves hurlers (from left to right) Bob Rush, Joey Jay, Carl Willey, Lou Burdette, Warren Spahn, and Bob Buhl helped Milwaukee to the second-best earned run average in the National League in 1959. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Behind Aaron’s consistent play, the Braves held a three-game advantage over the Giants by May 26, when they returned to Milwaukee for a fifteen-game home stand. Looking to take the opener against Pittsburgh, Fred Haney loaded his powerful lineup with seven right-handed bats and put ace Lou Burdette on the hill. The Pirates countered with Harvey Haddix, a left-hander sporting a mediocre 3–2 record. As threatening weather limited the County Stadium crowd to just 19,194, Haddix masterfully took the game into the deep innings without a base runner. Even though the Pirates couldn’t commandeer a lead, Haddix stifled the hot bats of Aaron, Mathews, and Adcock. After Haddix struck out Andy Pafko, got Johnny Logan to fly out, and sent Lou Burdette down swinging in the bottom of the ninth, he had pitched a perfect game. But since the Pirates had also failed to score, the game was forced into extra innings.

Surviving into the twelfth inning without incident, Haddix made baseball history as he kept pitching on heart and adrenaline. Nobody had ever pitched a no-hit game for more than eleven innings, much less a perfect game for more than nine. The Milwaukee crowd encouraged him with standing ovations after every inning. Since the Pirates couldn’t get to Burdette either, the game continued into the Braves’ half of the thirteenth inning—when Braves second baseman Felix Mantilla hit a routine grounder to the Pirates’ third baseman Don Hoak. After fielding the ball, Hoak threw it into the dirt, causing it to bounce off first baseman Rocky Nelson’s knee. “I’ll never forget that play,” Haddix acknowledged. “Hoak had all night after picking up the ball. He looked at the seams … then he threw it away.”

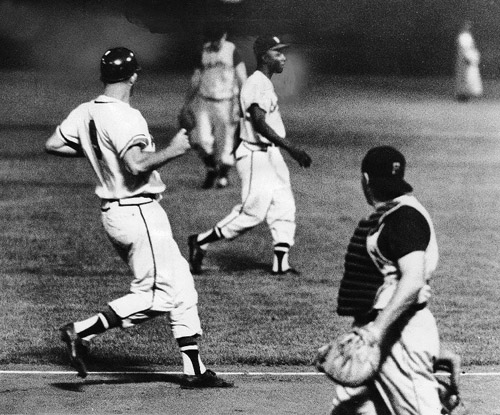

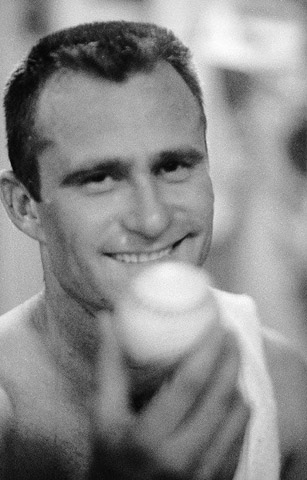

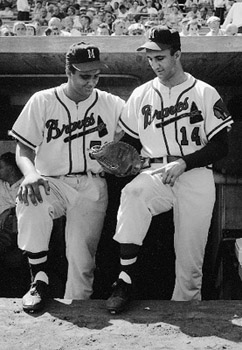

After Harvey Haddix’s (pictured) attempt at baseball perfection, Bob Buhl admitted players in Milwaukee’s bullpen were stealing Pirates catcher Smoky Burgess’s signs and placing a towel on the bullpen fence in such a way to signal fastball or breaking ball to the Braves batters. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

With the perfect game lost, Haddix focused on preserving his no-hitter as Mathews sacrificed Mantilla to second. Then Haddix decided to intentionally walk Aaron and pitch to Adcock. On the second pitch, Adcock connected for a deep drive toward right center that dropped into the bleachers for a home run. In one swift stroke, Haddix had lost his no-hitter and the game. While Adcock circled the bases, he was called out at third, and confusion ensued. Once Mantilla scored, Aaron—who thought the game had officially ended—passed second and turned toward the dugout. “He hadn’t seen the ball clear the fence, but he was watching the winning run. All he cared about was winning the game,” Mathews explained. Aaron’s base-running gaff reduced Adcock’s game-winning homer to a game-winning double. The next day National League president Warren Giles ruled that since both runners had been called out—Aaron for leaving the field and Adcock for passing him—the final score should be 1–0. The controversy distracted people from the fact that not only had Harvey Haddix just pitched a perfect game, but Lou Burdette had beat him. “That was the real story,” Mathews proclaimed. “Burdette was a sleeper. He never got enough credit for the type of pitcher he was, as good as he was.”

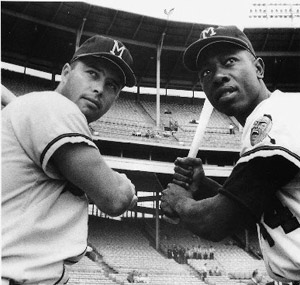

A rare base-running mistake by Henry Aaron (center) negated Joe Adcock’s (left) homer. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Burdette had struck out only two Pirates but hadn’t walked anybody. The following winter, he referred to his performance when requesting a raise. “Who pitched the greatest ballgame ever?” Burdette asked during negotiations. “Harvey Haddix,” general manager John McHale answered. Pausing only a moment, Burdette replied, “I beat him.”

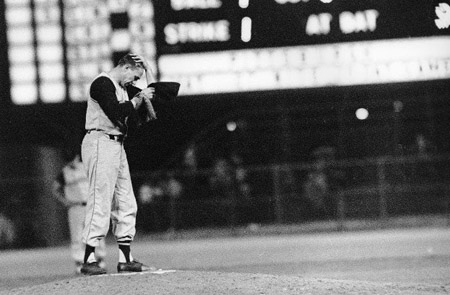

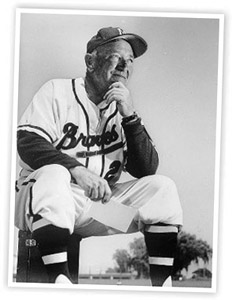

Skipper Fred Haney was criticized and second-guessed throughout his tenure as the Braves’ manager. (WHI IMAGE ID 54480)

Despite the Braves’ holding onto first place in the National League standings for all but one day between May 13 and July 4, a growing faction of critics was questioning the team’s leadership. “Haney had been hired to replace the easy-going Charlie Grimm, to bring discipline and firm guidance to a free-spirited, headstrong group of players,” Bob Buege asserted in The Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy. “Under Haney, though, the Braves were not terribly different from the way they had been under Grimm.”

Second-guessers from the clubhouse, press box, and grandstands considered Haney’s conservative bunting strategies the reason the team couldn’t pull away from the rest of the National League pack. “Fred Haney had a different way of managing. I don’t think he adapted to the players that we had on the ball club,” Eddie Mathews said. “He was going to manage his way regardless of what we had going on out there, and I think that did hurt us.”

As rumors of Haney’s retirement began to circulate, the Braves’ new executive vice president publicly came to his defense. “Ballplayers,” Birdie Tebbetts explained to reporters, “are the poorest possible judges of a manager’s ability, for the most part. That’s because each ballplayer is the central figure in his own little world. Everything rotates around him, and that is how he judges everything, by how it affects his life. A manager has a bigger scope. His life involves every man on his club. The team is important to him, and yet the team is 25 different people, or more.”

At the All-Star break, the Braves and Giants were tied atop the National League standings with the Dodgers trailing by only a half game. For 1959’s Midsummer Classic, baseball instituted a revolutionary format change to give West Coast fans an All-Star Game of their own. The two All-Star Games were loosely labeled the Eastern Game and the Western Game, and the second game was scheduled for August 3 in Los Angeles. The Braves were well represented in the Eastern Game, played on July 7 in Pittsburgh. Although Mathews was no longer on pace to eclipse Ruth’s season home-run total, he was selected as the National League’s starting third baseman; joining him in the starting lineup was Henry Aaron, unanimously selected to start by the voting players even though his efforts to hit .400 for the season had cooled. Also featuring Burdette, Crandall, Spahn, and Logan, the National League jumped out to an early lead on a Mathews homer. In the eighth, Aaron singled in the tying run and scored the deciding run after Willie Mays knocked a triple to seal the Nationals’ 5–4 victory. In the Western Game, played on August 3 in Los Angeles, the only Braves who saw playing time were Aaron, Mathews, and Crandall; Burdette, Logan, and Spahn rode the pine during the National League’s 5–3 loss.

Johnny Logan enjoyed one of his best seasons at shortstop in 1959 with a .975 fielding average and only eighteen errors. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

As one of the most mechanically sound catchers of his era, Del Crandall led all National League catchers in 1959 in putouts, assists, double plays, and fielding percentage while making only five errors all season. (ALL-AMERICAN SPORTS, LLC)

Eddie Mathews led the National League with forty-six home runs in 1959 and was named Wisconsin’s athlete of the year. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Red Schoendienst returned for five games during the final month of the 1959 season. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

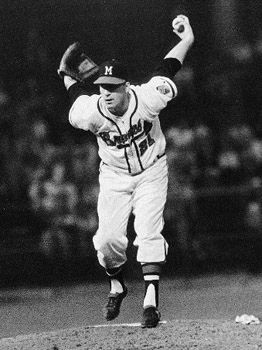

In 1959 Warren Spahn led the league with twenty-one complete games, tied teammates Lou Burdette and Bob Buhl with four shutouts each, and tied with Burdette and the Giants’ Sam Jones for the league lead in wins, with twenty-one. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The loss marked the end of a tough streak for the Braves between the All-Star Games. On July 9 Milwaukee and Spahn had lost a thirteen-inning heartbreaker to the Dodgers. The defeat sent the Braves spiraling down the standings with seven consecutive losses. Hoping to reinvigorate the team with some much-needed veteran leadership, general manager John McHale acquired several aging superstars, first trading for former American League batting champion Bobby Avila in late July to fill the absence left by Red Schoendienst. (Despite hitting a game-winning, ninth-inning homer in his first game as a Brave, Avila soon went cold at the plate and would finish the season with a paltry .238 average.) Because Johnny Logan, Eddie Mathews, Wes Covington, and Billy Bruton were nursing late-season injuries, McHale purchased an aging Enos Slaughter from the Yankees, but Slaughter played sparingly in just eleven games.

By September Milwaukee had managed to lose more games than they had won since the All-Star break. With only three weeks left in the season, they sat in third place behind the Dodgers and Giants, and their hopes of repeating as National League champs were slim. “I thought a lot of players were unconsciously sitting back and waiting for someone else to do the job,” Frank Torre later told a Sport magazine reporter. “A month and a half before the season ended, we suddenly realized that we all had to pitch in and we went out and played baseball.”

The Braves won thirteen of their next sixteen games. With a week to go in the regular season, they had reclaimed first place. Several players fed the surge, and nobody in Milwaukee’s lineup was hotter than Eddie Mathews, who had connected for eleven homers in the last twenty-five games. Just as important were catcher Del Crandall’s contributions from both behind and in front of the plate. “I don’t know what we would have done without him,” Fred Haney told the press. “He was our clutch hitter. Don’t let his average fool you. He’s been one of our key guys—a real lifesaver.”

After having spent most of the season recovering from tuberculosis, Red Schoendienst rejoined the club for the final pennant push. “He hardly played any at all, but I think that just having him on the bench helped the team get its pride back,” Aaron recalled.

On the season’s second-to-last day, Milwaukee trailed the first-place Dodgers by a game. Desperate for a win, the Braves again turned to their most seasoned warrior, Warren Spahn. Behind a cannon filled with baseballs that wiggled, sank, curved, and looked faster than they were, the crafty lefthander handcuffed the Phillies 3–2 for his twenty-first victory of the season. Meanwhile, ninety miles south in Chicago, the Cubs shelled the Dodgers 12–2, creating a first-place tie.

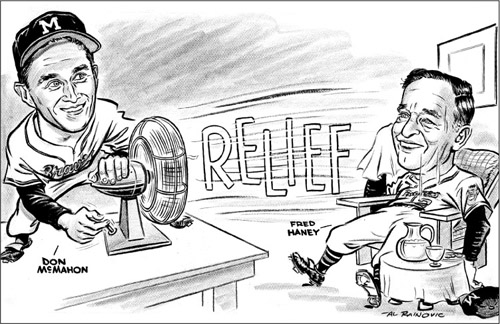

Don McMahon led the senior circuit in 1959 with fifteen saves. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 227)

For the fourth year in a row, Milwaukee’s season came down to the last possible day, as the Dodgers and Giants were still capable of winning the pennant. But after San Francisco dropped a doubleheader and County Stadium’s out-of-town scoreboard posted that the Dodgers had downed the Cubs on September 27, the Braves realized that to stay alive, they’d have to win their season finale against the Phillies. “The situation had certain similarities to 1956, except now we were a game behind instead of a game ahead,” Mathews recalled.

Facing the Phillies with no room for error, Bob Buhl kept the game deadlocked at one into the seventh inning. When Milwaukee rallied for three unearned runs in the home half of the seventh, Don McMahon pitched the last two innings to secure the win—his fifteenth save of the year. The Braves had pulled into a regular-season tie with the Dodgers, with an identical 86–68 record. The pennant would be decided in a three-game playoff series, with the winner to face the Chicago White Sox in the World Series. “As far as we were concerned, the hard part was over, because we had survived the pennant race and we were sure—everybody in Milwaukee was sure—that we were the superior team,” Aaron said.

Milwaukee hosted the series’ first game at County Stadium with only 18,297 fans braving the cold and drizzly weather. “After playing in front of big crowds for so many years, we came to a championship playoff and County Stadium wasn’t even half full. It was weird,” Eddie Mathews remembered. “Maybe the fans were all waiting for us to play the World Series.”

In the Braves’ clubhouse, manager Fred Haney faced a dilemma: who to start for Game One. His aces, Spahn and Burdette, needed a rest after pitching practically every day to get the Braves into the postseason. Haney was forced to start the inconsistent Carlton Willey, and the Dodgers immediately took advantage, getting an early run in the first. The Braves rallied for two in the second and forced Los Angeles manager Walter Alston to lift starter Danny McDevitt for rookie reliever Larry Sherry after only one and one-third innings. Sherry held the Braves scoreless for seven and two-thirds innings. When the Dodgers took a 3–2 lead on John Roseboro’s solo homer off Willey in the sixth, it was all Los Angeles needed to secure the Game One victory. The Braves were unfazed by their 1–0 series deficit. “On the plane to Los Angeles that night, we were still sure we were going to win it,” Aaron professed. “We even sat and talked about how we were going to use our World Series tickets, and who was coming in for the games.”

The Los Angeles Coliseum hosted Game Two the following day. With the Braves’ pennant hopes hanging in the balance, they sent Lou Burdette to the mound to battle the Dodgers’ 1959 National League strikeout king, Don Drysdale. Milwaukee jumped on the Los Angeles hurler for two runs in the top of the first and another in the second. In the bottom of the seventh, with the Braves ahead 4–2, Dodgers left fielder Norm Larker barreled into Johnny Logan while attempting to break up a double play. Though the Braves got both outs, they lost Logan, who was carried off the diamond on a stretcher and replaced by Felix Mantilla. After Milwaukee got another run in the eighth, Burdette entered the bottom of the ninth inning with a 5–2 cushion. “We looked truly superior, like the superior team that we were, all the way into the ninth inning,” Aaron recalled.

Johnny Logan was injured in Game Two when the Dodgers’ Norm Larker attempted to break up the double play. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The Dodgers connected for three consecutive singles off Burdette to start the bottom of the ninth. With the bases loaded and nobody out, Haney called on Don McMahon to quash the mounting rally. “You still had to like our chances with McMahon going,” Aaron admitted. “He was big and strong and at the peak of his relief-pitching career then.” But Norm Larker greeted the Braves’ reliever with a single to left that scored two and brought the tying run to third. Still with nobody out and the lead cut to 5–4, Haney took action. “The sight of Spahn, our ace, warming up in the bullpen was enough to tell me that somebody higher than me was also pretty worried,” Aaron observed. Spahn took the mound to retire the first batter he faced. Then pinch hitter Carl Furillo launched a deep pop fly. Aaron speared it with his glove for out number two, but Gil Hodges tagged up from third and tied the score at five.

With the Braves’ lead vanquished, their bats remained quiet as the game went into extra innings. The bottom of the twelfth inning found relief specialist Bob Rush looking to extend the game for Milwaukee. But with two outs, Rush yielded a walk to Gil Hodges, and Joe Pignatano followed with a single. Then Furillo connected for a bouncer up the middle that took a high, twisting hop over the second-base bag. Shortstop Felix Mantilla went hard to his right and gloved the ball. Making a quick turn to get the throw to first, Mantilla threw off-balance, and the ball went errantly wide as Hodges hustled around third to score the winning run. “Nobody blamed Felix. It was just a throw in the dirt that Frank Torre couldn’t scoop out. Those things happen,” Eddie Mathews remembered.

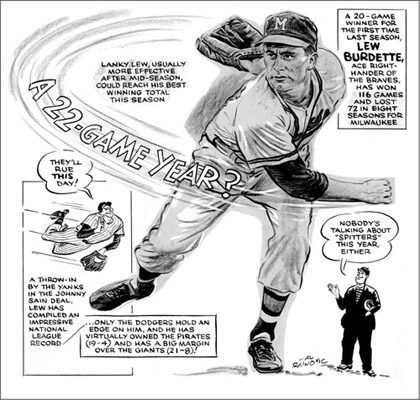

Lou Burdette took the mound for Game Two of the 1959 playoffs against the Dodgers hoping he’d clinch his twenty-second win of the year. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 82)

Convinced all season that no team in the league could touch them, the Braves were left to mope around their clubhouse after the unexpected 6–5 loss. As players changed out of their tomahawk-clad flannel jerseys for the last time that season, the showers echoed. “I’ve never heard such loud water in my life. It seems that water runs twice as hard and sounds twice as loud in a quiet clubhouse as it does in a happy clubhouse,” Aaron said.

Back in Milwaukee, the abundance of fans who once cheered foul balls upon the Braves’ arrival in 1953 was noticeably shrinking by 1959. Despite falling just short of their third consecutive World Series, the Braves suffered their second consecutive dip in attendance with only 1.7 million fans. “Maybe the novelty had worn off. I don’t know,” Mathews reflected years later. “The Braves’ season attendance dropped about a quarter-million, but it was still higher than any other team except the Dodgers in that big Coliseum.”

Although County Stadium hosted fewer fans, it didn’t keep those who attended from being extensively vocal about the team’s shortcomings. “The 1959 season had been filled with so much promise that its wrenching finish was difficult to accept,” Braves historian Gary Caruso attested.

The discriminating public and press placed most of the blame on manager Fred Haney. Just five days after the season-ending loss, Haney caved in to the pressure and resigned. “I think Haney is the most underrated manager I’ve known. He belongs with the very best, and he has a record to prove it,” declared Braves publicity director Donald Davidson in his autobiography, Caught Short. “Over a four-season span, from 1956 through 1959, Fred won two pennants, lost another by a game, and lost a fourth in a playoff.”

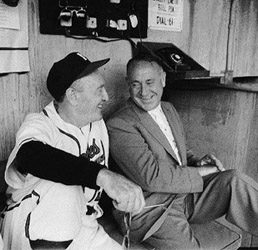

Fred Haney (pictured left with owner Lou Perini) had the highest winning percentage of any manager in baseball during his time with the Braves between 1956 and 1959. (WHI IMAGE ID 49325)

Several of the Braves’ veterans came to their manager’s defense, including Warren Spahn. “We had better take stock of ourselves and give some thought as to why we didn’t win the pennant instead of just blaming the manager,” he told reporters. “I don’t think it was Haney’s fault. I thought he did a good job.”

Outfielder Wes Covington agreed. “Remember, Haney didn’t build this club; it was here when he came,” he commented to the press. “If we had won the pennant, nobody would have said anything about bunting or running. Maybe there are things he could have done different, but he should be given credit where credit is due.”

Others were quick to applaud Haney’s departure, including the Braves’ often brash but passionate shortstop. “When they announced Haney was out, you can bet few players were sorry,” Johnny Logan was quoted in the New York Post. “Anybody could manage with what we had. We should have won by ten games.”

With Haney gone and absentee owner Lou Perini spending less and less time in Milwaukee, the brunt of the fans’ discontent quickly shifted to the Braves’ front office. It was especially evident in the newspaper editorials, in which fans voiced their frustration about Bostonian Lou Perini becoming an “absentee owner” and suggested he was showing little interest in Milwaukee as anything other than a profit center for his baseball club. Still, few could have foreseen the path the franchise was taking. “I still had no feeling at the time of being a part of an empire that was in the state of collapse,” Henry Aaron confessed in his autobiography Aaron. “Changes began to take place during the winter. By the next spring, the Braves were not the same Braves.”

Immediately following Fred Haney’s departure, speculation spread about a likely replacement. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 89)

♦ ♦ ♦

Hoping to recapture the charm that had once made Milwaukee the Camelot of baseball, the Braves hired Charlie Dressen as their new manager on October 23, 1959. Dressen’s baseball pedigree included eight seasons playing third base for the Giants and Reds. Managing Cincinnati from 1933 until he was dismissed in 1937, Dressen never took his team out of the second division. In 1951 he went to Brooklyn and won two pennants for the Dodgers. After Dressen demanded a long-term contract, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley replaced him in 1954 with Walter Alston. Dressen later managed the Washington Senators for three dismal seasons and returned to Walter Alston’s coaching staff with the Dodgers before arriving in Milwaukee. Braves management believed their new skipper’s vast managerial experience would reinvigorate the team’s roster—essentially the same lineup that had finished a game short of the pennant in 1959. According to general manager John McHale, “[Charlie Dressen] … took over a very talented and very difficult club to manage. There were a lot of stars who each wanted his own way. It took a very strong hand to keep things together.”

Along with a firm hand, Dressen brought optimism to the Braves clubhouse, believing he could turn around the team’s fortunes. “He never managed a ball game he didn’t think he—not his players—could find a way to win,” Gary Caruso noted in The Braves Encyclopedia.

New manager Charlie Dressen brought with him a reputation of strict discipline. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

But the players were a little more skeptical of his abilities. Eddie Mathews recalled, “Wherever he was, Dressen was always controversial, always flamboyant and outspoken. He had a well-deserved reputation for using the pronoun ‘I’ more than anybody else, seemingly at least once in every sentence.”

When asked at the press conference announcing his arrival if the Braves would win the 1960 pennant, Dressen told reporters, “I honestly don’t know, but write this down. I’ll win as many games as the Braves did last year and I’ll beat the Dodgers.”

Forcing his small-ball style of bunting and stealing onto the power-hitting club of veterans, Dressen struggled to manage the Braves’ plethora of personalities. “Dressen knew as much about baseball as any manager in the game, but he wasn’t the right man for our club,” Henry Aaron said. “We were a veteran team, and guys like Spahn and Burdette didn’t need to be told how to do their jobs.”

Dressen began his quest to capture Milwaukee’s third National League pennant in four years on April 12, 1960. A good crowd of 39,888 optimistic fans filed through County Stadium’s gates for the home opener against the Pittsburgh Pirates to witness another fine pitching performance from Warren Spahn. Joe Adcock hit the game-winning two-run home run in the eighth, and Don McMahon earned the victory in relief, with Lou Burdette earning the save in the ninth. The exciting 4–3 win helped to rejuvenate the Milwaukee fans, but it soon became evident that the Braves no longer had the same draw. County Stadium, which had been used to packed crowds near forty thousand, was now regularly hosting less enthusiastic crowds of ten thousand to fifteen thousand.

General manager John McHale quickly found himself juggling his aging roster, which now included several struggling stars. Red Schoendienst opened the season at second base but was relegated to benchwarming after several uncharacteristic fielding errors and a low batting average implied that his bout with tuberculosis had affected his everyday abilities. Wes Covington, who had reported to spring training out of shape, was sidelined for much of the year with a series of nagging injuries. Even the weather seemed to be conspiring against the Braves: “Another thing that hurt us was that we had 12 games rained out the first part of the season,” Dressen told reporters later. “The doubleheaders piled up and when we played them off later on, [Joey] Jay and [Juan] Pizarro couldn’t win for us.”

In May Milwaukee’s relievers blew several late-inning leads as seven of the team’s eleven losses that month were credited to the bullpen, leaving the Braves’ manager frustrated. “The biggest disappointment on the Braves’ 1960 staff,” Dressen commented later to Sport magazine, “was Don McMahon. After three fine years as a relief pitcher, McMahon slumped badly, posting a 3–6 record and 5.91 earned run average.”

After finishing May at .500, the Braves improved during June and were in second place by the All-Star break at 43–34, just five games behind first-place Pittsburgh. The first game was played on July 11 at Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium, with Henry Aaron, Joe Adcock, Del Crandall, and Eddie Mathews elected to the National League’s starting lineup. Pitcher Bob Buhl appeared in relief during the National League’s 5–3 victory. The teams moved to Yankee Stadium on July 13 for the second game, and Eddie Mathews hit a two-run homer in the second inning to help the National League sweep the Midsummer Classic with a 6–0 shutout.

The Braves returned from the All-Star break hot. Winning six in a row and eight of their next ten, they claimed a share of the lead with Pittsburgh on July 24. However, as Milwaukee enjoyed a day off, Pittsburgh beat St. Louis to reclaim first place outright. The Braves lost eleven of their next sixteen games due to sloppy fielding, lack of clutch hitting, and the bullpen’s continued ineffectiveness. A disastrous August found them plummeting into fourth place—seven games behind the Pirates.

Braves office personnel, including (left to right) Mary Miklas, Donna Hempton, and Anita Seckinger, sported dark blazers decorated with the club insignia, similar to those worn by the players during road trips. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Milwaukee’s frustrations culminated in a slugfest during the first game of a doubleheader on August 15 at Crosley Field in Cincinnati (whose Reds had returned to their traditional nickname in 1960 as the Red Scare waned). When Frank Robinson slid into third base in the seventh inning, Mathews took exception. “I had him out by a mile,” Mathews remembered. “I didn’t go out to confront him. I stayed on the bag and he came barreling into me. As he slid in, hard, he swung his arm up and caught me on the side of the head.” Both known as aggressive players, Mathews and Robinson didn’t hesitate to exchange words, and a scuffle erupted. “ ‘Frank, don’t come in here like that,’ I told him. ‘I’ve had enough of that garbage.’ He responded with some very unfriendly phrases. I threw my glove down and we went at it,” Mathews recounted. The burly third baseman knocked Robinson down and landed a couple more solid punches. By the time the two were separated, Robinson had a swollen eye, bloody nose, and jammed thumb; Mathews was ejected. The Braves went on to lose the game, but both players were back in their lineups for the nightcap, and Robinson’s return helped the Reds sweep the doubleheader.

Fueling the Braves’ frustrations were manager Charlie Dressen’s increasingly strict policies. “Charlie believed in club discipline. He had a long list of rules and regulations and enforced curfews, but some of the Braves thought they could outsmart him,” Davidson remembered. “He employed an old trick to catch night owls. After 1:00 a.m., he’d give the hotel elevator operator a baseball and tell him to get autographs of all the players he saw… . In the morning, Charlie would pick up the ball and get an automatic list of players who had violated curfew.”

Billy Bruton had a career season in 1960 as he led the league in runs and triples and finished fourth in hits and fifth in steals. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Eddie Mathews (right, looking at hand) was left bloodied after his brawl with Cincinnati’s Frank Robinson. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

But two of the cleverest Braves caught on to the trick and started signing other names on the ball to avoid getting caught. “Spahn and Burdette used to make Dressen’s life miserable,” future Milwaukee catcher Joe Torre recalled. In another incident, “Dressen was hiding in the bushes of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, spying on the players as we would come and go from our cabanas around the main lawn in front. While Dressen was in the bushes keeping an eye on us, Burdette tossed a firecracker in there, scaring the hell out of him.”

Milwaukee’s sluggers led the National League with 170 round-trippers, with Henry Aaron and Eddie Mathews finishing first and second in RBIs and second and third in the home-run race behind Ernie Banks of the Cubs in 1960. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

The mischievous duo also set Dressen’s shoelaces on fire during a pregame pontification right before he walked toward home plate for the lineup meeting. “The hot foot was just epidemic in baseball,” future Brave Bob Uecker remembered in his biography, Catcher in the Wry. “Players would be sitting on the bench, watching the game, and you would crawl from one end of the dugout to the other, sticking matches in their shoes and lighting them, and then see those feet go up like someone running the keyboard on a piano.”

Despite their disdain for Dressen, Spahn and Burdette kept things serious on the mound. On August 18 Burdette was looking to clinch his fourteenth victory of the season against Philadelphia and reduce the Braves’ seven-and-a-half-game deficit behind the first-place Pirates. Scheduled to face him was former teammate Gene Conley, who had found success off the mound and on the basketball court since being traded away from Milwaukee. (As a member of Red Auerbach’s Boston Celtics, Conley was the first pro athlete to win championships in two major sports as a member of three consecutive NBA title teams beginning with the 1958–59 season.)

Renowned practical jokers Warren Spahn and Lou Burdette were all business on the mound for Charlie Dressen as Spahn secured league bests with twenty-one victories and eighteen complete games while Burdette hurled nineteen wins. But the team’s overall ERA of 3.76 in 1960 was fifth in the league, the lowest since arriving in Milwaukee. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

As the hot summer night progressed, Conley and Burdette exchanged goose eggs on the scoreboard. While the sparse County Stadium crowd of 16,338 fans looked on, Conley soon realized his former teammate was pitching flawlessly. “He had good control, moved the ball around and threw that sinker. He got a lot of ground balls,” Conley recalled.

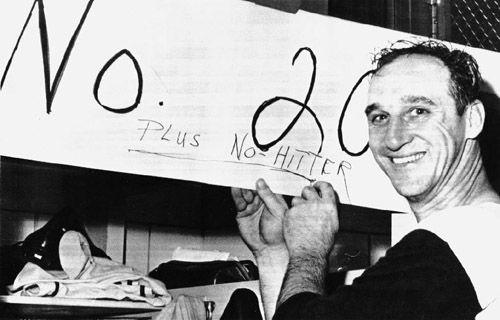

In the top of the fifth inning, Burdette hit the Phillies’ Tony Gonzalez with a pitch to ruin his perfect game. But when Gonzalez was erased in a double play, the Braves’ right-hander had still faced the minimum number of batters through five innings. Both teams’ bats stayed quiet as “Fidgety Lou” and “Long Gene” took a scoreless game into the bottom of the eighth. When Burdette led off with a double, he scored the Braves’ first run on Billy Bruton’s double to right. Taking the slim 1–0 lead into the top of the ninth, Burdette recorded two more outs. Then his ninety-first pitch of the game sailed off the bat of pinch hitter Bobby Smith. When it landed in Henry Aaron’s glove for the final out, Burdette had faced the minimum of twenty-seven batters and achieved his first career no-hitter.

When thirty-nine-year-old Warren Spahn took the mound against the Phillies on September 16, he hoped to clinch his eleventh career twenty-win season—and perhaps match his roommate Burdette’s feat of a month earlier. Only 6,117 die-hard fans clicked through County Stadium’s turnstiles after an all-day rain threatened to cancel the game. The smallest night crowd in Milwaukee Braves history got to witness the Braves build a 4–0 lead as Spahn cruised through the Philadelphia lineup for eight and two-thirds innings. Then Phillies’ second baseman Bobby Malkmus slapped a sharp grounder off Spahn’s glove that ricocheted toward shortstop Johnny Logan. Dashing in to scoop it up, Logan rifled a throw to first baseman Joe Adcock. The ball sailed a bit wide, but Adcock grabbed the throw with his foot on the bag for the out. After the game, Spahn had to credit Burdette. “If he hadn’t pitched his no-hitter, I don’t think I would have gotten mine,” Spahn joked with reporters. “When Lou pitched his, I just had to go out there and pitch one myself.”

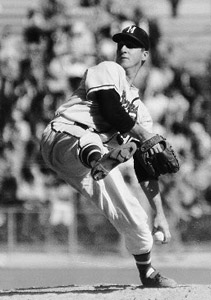

Against the Phillies on August 18, 1960, Burdette threw just ninety-one pitches while facing the minimum twenty-seven batters for his first no-hitter. (WHI IMAGE ID 49233)

A month later, veteran left-hander Warren Spahn walked only two Philadelphia batsmen during his first career no-hitter, which also happened to be his twentieth win of the season. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Lou Burdette allowed only one batter to reach base during his no-hit performance against the Phillies. (WHI IMAGE ID 49231)

Joe Adcock was second to none in the field in 1960, leading all National League first basemen in defense. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Despite the two late-season no-hitters from Burdette and Spahn, Milwaukee’s pennant hopes never rebounded from the team’s devastating August. Their second-place finish with an 88–66 record was seven games behind the eventual world champion Pittsburgh Pirates. Dressen had delivered on two of his preseason promises: the Braves won more games than the year before, and they finished six games ahead of the Dodgers. But it was small consolation; the Braves’ season attendance continued to decline. For the second straight year, a disturbingly new low was established in Milwaukee as fewer than 1.5 million customers paid to watch the Braves play at County Stadium. It was concrete evidence that the “Milwaukee Miracle” was over.

♦ ♦ ♦

After their disappointing second-place finish in 1960, the Braves spent their off-season dismantling their roster of core players. “We were all getting older. It was inevitable that something like that would happen, but you still hate to see it happen,” Eddie Mathews admitted. “Ever since the Braves moved from Boston, our lineup had been pretty much the same, very consistent.” Realizing the roster still possessed trade value, general manager John McHale focused on bolstering the team’s infield defense. To receive All-Star second baseman Frank Bolling from Detroit, the Braves sent away one of Milwaukee’s first heroes, Billy Bruton. “That was the first real sign that John McHale was going to clean house,” Mathews said.

But McHale’s savvy trade for Bolling was overshadowed by his decision to deal away pitchers Joey Jay and Juan Pizarro after the organization labeled them as underachievers. “What really hurt was losing the young Braves,” Henry Aaron noted in his 1991 autobiography. “I’ve always felt that we would have won some more championships if we had held on to Pizarro and Jay.”

In return for Pizarro and Jay, Milwaukee got two-time All-Star and three-time Gold Glove Award–winning shortstop Roy McMillan. “He wasn’t much with the stick, but he could play shortstop with the best of them,” Mathews remembered. To make room for Bolling, McHale gave second baseman Red Schoendienst his unconditional release—to the dismay of many of the players. “That move made no sense to us,” Mathews said. “They didn’t trade him for anybody; they just let him go.”

With McMillan assuming the everyday shortstop duties, Johnny Logan became expendable, and McHale traded him to Pittsburgh at midseason for outfielder Gino Cimoli. It was a loss that would be felt by both players and fans. Henry Aaron noted, “Johnny was great for team spirit, the most humorous man I ever played with.”

After thirteen seasons as a fixture at shortstop in Milwaukee—five with the Brewers, eight with the Braves—Johnny Logan was traded to the Pirates for journeyman outfielder Gino Cimoli. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Realizing Wes Covington was never going to be the answer in left field, McHale acquired three-time All-Star Frank Thomas from the Cubs. “He hit quite a few home runs for us and gave us help in the outfield, which we needed,” Mathews said. “Then after the season the people upstairs sent him to the Mets. What their thinking was, I have no idea. John McHale did a lot of things I never understood.”

By spring training McHale had assembled a team vastly different from the one of years past. “The Braves’ personality was being changed to match the desires of the new personality of the front office: Tebbetts, McHale and Dressen,” Aaron acknowledged.

As the outsiders and transients replaced the familiar faces in the Braves clubhouse, Milwaukee’s biggest change during 1961’s spring training was the players’ new housing arrangements. “That happened to be the first spring camp in which the Milwaukee Braves wanted every player on the team to stay together—black and white players alike,” Joe Torre remembered. According to Torre, this didn’t suit the Braves’ usual exclusive hotel in Bradenton, and they moved to the nearby Twilight Hotel in Palmetto, and “even there they had to feed us in a private room where no one else could see blacks and whites eating together.”

During the Braves 1961 spring training, several Wisconsin natives attempted to make the opening day roster, including (clockwise from bottom left) Dennis Overby, Dave Fracaro, John Braun, Clair Hickman, Bob Botz, and Bob Uecker. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

In addition to rooming and eating together, the Braves ordered all race signs dropped at their Bradenton ballpark. “I wish I could say that we were a better team with segregation behind us, but the fact is that while we were coming together off the field, we were coming apart on it,” Aaron confessed.

Back in Milwaukee, a war was brewing—one that divided a city from its ball club. “The people on the county board, which controlled the stadium, got greedy,” Mathews said. “They decided they could make some money by banning carry-ins and making the fans buy beer from the concession stands and vendors, at a big mark-up, of course.”

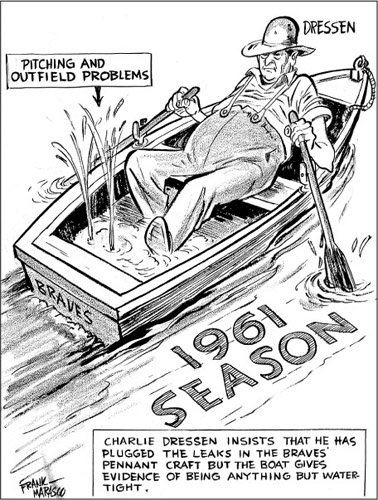

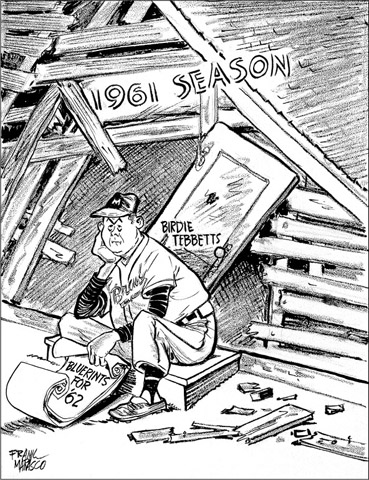

Restless Braves supporters hoped the team’s off-season roster tinkering would brew up another pennant for Milwaukee in 1961. (COURTESY MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, FRANK J. MARASCO CARTOON COLLECTION)

Fans were left to their own devices after alcohol was banned at County Stadium in spring 1961. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

The already-apathetic fans—many of whom worked at the local breweries—found the ban insulting. The first indication that the beer carry-in ban had alienated even the most devoted of fans came on the chilly afternoon of April 11, when County Stadium was only two-thirds full for the Opening Day game against the Cardinals. Just 33,327 fans were in attendance to watch Warren Spahn lose a 2–1 heartbreaker in the tenth inning.

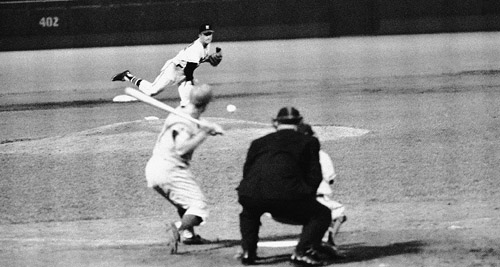

On April 23 the seemingly ageless Spahn celebrated his fortieth birthday by beating the Pirates for his 289th career victory. Five days later, Spahn was set to face the San Francisco Giants and one of the most potent slugging crews in the National League. “I knew my arm and I knew my hitters,” Spahn said, “and as I lost sheer speed, I went for variety.” Another anemic County Stadium crowd of 8,518 watched Spahn mow down the Giants’ Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Felipe Alou, Harvey Kuenn, and Orlando Cepeda with a mixture of screwballs and sliders. The Braves took an early first-inning lead, which was all the southpaw needed, as he went on to face the minimum twenty-seven batters in the Braves’ 1–0 victory. Striking out nine while allowing only a pair of walks that were erased by double plays, Spahn became the second-oldest man to hurl a no-hitter in major-league history, behind Cy Young. “It was so easy, it was pathetic,” Spahn remembered. “Everything went my way, and they kept guessing wrong. But let’s just face it; I was just plain lucky.” After going nearly sixteen seasons without a no-hitter, Spahn had pitched two within a span of six starts. “Here I waited nearly a lifetime to get my no-hitter, and no sooner do I get it than I come up with another. That’s life.”

Two days later a meager crowd of 13,114 dragged itself to the ballpark for the series-deciding rubber match against the Giants. With Willie Mays in an 0-for-7 slump, the Braves looked ready to reclaim the National League’s top spot. Mays had played through a stomachache all weekend but was feeling better by Sunday. By the end of the day, the Giants had throttled the Braves 14–4, setting a National League record of eight home runs—four off Mays’s bat. “You’re satisfied if you get two in a game, but when you get three, that’s something you never expect,” Mays confessed to reporters after the game. “Four? That’s like reaching for the moon.”

The Braves continued to play mediocre ball, flirting with .500 through most of May. By the end of the month, they sat in fifth place at 19–20, already five and a half games out of first. Nagging injuries began to catch up with Milwaukee, beginning with catcher Del Crandall, whose hampered throwing shoulder landed him on the disabled list. “Losing Del hurt us. He was an all-star practically every year and a strong influence on our pitching staff,” Mathews said.

Instead of instigating a trade, John McHale turned to Milwaukee’s farm system and called up a pudgy catcher from the same home in Brooklyn that had provided defensive standout first baseman Frank Torre. After winning the batting title with the team’s minor-league affiliate in Eau Claire, Joe Torre and his hot bat became the Braves salvation behind the plate. “[Del Crandall’s] backup, Charlie Lau, who became a famous hitting coach, had been filling in, but now it looked as if Crandall would be out longer than the Braves first thought,” Torre recalled. Since he had hung out in the clubhouse with his older brother Frank, Joe immediately fit in with the veteran-filled roster. “Spahn and Burdette were … like older brothers. They used to take me to the movies with them in the afternoon and to restaurants at night. Dressen, however, wasn’t too hot about me striking up a friendship with them. ‘Don’t hang around Spahn and Burdette,’ he’d say. ‘They’re like the Katzenjammer Kids.’ ”

Catcher Joe Torre (on left with brother Frank) finished second behind the Cubs’ Billy Williams in the 1961 National League Rookie of the Year voting. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

It seemed Dressen focused more on battling with his ballplayers than with the rest of the National League in 1961. As the season progressed, Dressen continued to eliminate player privileges, from revoking their ten-dollar meal per diem to serving sandwiches rather than full meals on team charter flights. But instead of motivating the players to perform better on the field, the changes only ignited their resolve against their manager. “Mathews and I used to sit in the clubhouse playing a card game called casino,” Henry Aaron remembered, “and Dressen would come by every few minutes to order us out to the field. We’d just stay there dealing hands until about two minutes before game time, with Dressen getting angrier every minute. But we were choirboys compared to Spahn and Burdette.” Following a doubleheader split in Philadelphia, “they started a fire in the back of our bus. When that happened, it was obvious that Dressen had lost control of the club.”

Despite growing dissension in the clubhouse, the Braves’ bats began to explode. On June 8 the Braves entered the seventh inning trailing the Reds 10–2, and Cincinnati right-hander Jim Maloney thought he was on his way to a complete-game victory. But after Frank Bolling led off with a single, Mathews followed with a home run. Still with no outs, Aaron followed with another home run to bring the score to 10–5. Maloney was lifted in favor of left-hander Marshall “Sheriff” Bridges, who was greeted with a Joe Adcock home run, followed by another fence-buster from left fielder Frank Thomas. By blasting four consecutive home runs, the Braves established a new major-league record while cutting their deficit to 10–6. In the eighth Mathews hit his second homer of the game to cap off the impressive slugging display, but the Braves couldn’t complete the rally and lost the game 10–8.

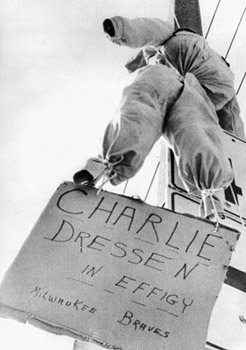

Another Braves manager was hung in effigy after a disappointing home stand found the Braves floundering in fifth place. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

The Braves’ rampage continued the next day at Chicago’s Wrigley Field as they hit four home runs, including a grand slam by outfielder Lee Maye, in an 11–10 loss. On June 10 Milwaukee hit four more homers, including one by Burdette, to pull out a 9–5 victory over the Cubs. Still at Wrigley on June 11 in the first game of a doubleheader, the Braves added two more homers in an 8–4 win, tying what was then the major-league record of sixteen in four games. By July 2 Milwaukee had connected for forty-six home runs in just twenty-one games, but its pitching staff prevented the team from gaining any significant ground in the pennant race.

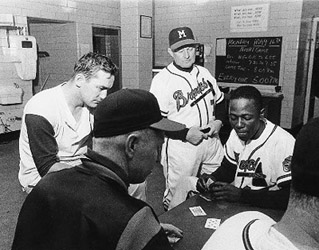

Manager Charlie Dressen (7) was never fond of the competitive card games that (left to right) Red Schoendienst, Johnny Logan, Henry Aaron, and Eddie Mathews (not pictured) played until just minutes before a ball game’s first pitch. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

After nearly seven years of dominance from the mound, Milwaukee’s pitching corps had begun to diminish. No lead was safe when Dressen went to the bullpen during the late innings as the Braves lost thirty-three one-run ball games. Their starting rotation still featured strong performances from its two aces but quickly became a refrain of “Spahn and Burdette and try to forget.” Collecting the league’s second-lowest number of shutouts with eight—four by Spahn, three by Burdette, and one by Bob Buhl—the Braves’ declining pitching staff was in severe depression. They missed Jay and Pizarro, who were having successful seasons in Cincinnati and Chicago. Milwaukee’s young arms in the farm system had yet to mature, and Carl Willey continued to disappoint after his stellar 1958 rookie campaign. Despite their unbridled power at the plate, the Braves’ pitching staff left them mired in fifth place by the All-Star break.

A hearty thirteen and a half games back of the Reds, Milwaukee sat three games under .500 with a 37–40 record when Aaron, Bolling, Mathews, and Spahn were named starters on the National League’s All-Star roster. The Midsummer Classic continued its doubleheader format, despite two years of mixed reactions from the fans. The first game, in San Francisco’s Candlestick Park on July 11, saw Spahn start and pitch three scoreless innings for the Nationals. Aaron singled in the tenth; then Willie Mays doubled, followed by a Roberto Clemente single that scored both runs. The Nationals had rallied for an exciting 5–4 victory.

The second All-Star Game, at Boston’s Fenway Park on July 31, showcased classic pitching as both teams managed to collect only nine hits total. Starters Aaron, Bolling, and Mathews represented the Braves, while Spahn rested in the bullpen. With the score deadlocked at one after nine innings, the game was called because of a downpour, making it the first Midsummer Classic to end in a tie.

Despite winning nine out of their previous ten games, the Braves entered August still trailing first place by eight and a half games. Warren Spahn had always dominated the second half of the season in previous years, but his 9–12 record as late as July 30 suggested that he had reached the twilight of his career. Nevertheless, when Spahn took the mound on August 4 in Candlestick Park, he earned his 299th career victory, leaving him just one elusive win away from baseball immortality.

Milwaukee struggled to keep afloat in the National League standings during the 1961 season. (COURTESY MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, FRANK J. MARASCO CARTOON COLLECTION)

A week later, 48,642 fans—County Stadium’s largest crowd in two years—arrived hoping to watch Warren Spahn join one of baseball’s most exclusive clubs: the three-hundred-win club. “I have always thought that one remark typified him,” Braves catcher Bob Uecker recalled. “The night he won his 300th, he was asked what it meant, how badly he wanted it. He looked surprised anyone would ask. ‘I wanted this one,’ he said. ‘I wanted the last one, and I want the next one.’ ” Only twelve men had won three hundred major-league games in history, with just six—Cy Young, Christy Mathewson, Eddie Plank, Walter Johnson, Grover Cleveland Alexander, and Lefty Grove—pitching in the twentieth century, and the barrier hadn’t been breached since Grove won his three hundredth and last game in 1941.

While Spahn prepared to face off against the Cubs’ rookie Jack Curtis, he felt the magnitude of the event. “Before I got close, I wasn’t too excited about it, because I figured winning 300 was bound to come eventually,” he explained. “But a few hours before the game, the pressure began to build. About 6:00 p.m. I wished the game would start right then and there. I’ve never done anything so tough in my life.”

At age forty, Warren Spahn led the National League in wins and complete games, shutouts, and earned run average. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Locked up in a one-all tie through the Cubs’ half of the eighth inning, Spahn needed some offensive assistance to secure the win. Journeyman outfielder Gino Cimoli slugged a home run to right center, giving Spahn the 2–1 lead he yearned for. But in the ninth inning, the seventh-place Cubs battled to the final pitch and conceded nothing. With two outs, Spahn got Jim McAnany to pop a soft fly ball to right. When it nestled into Aaron’s glove for the final out, Spahn was mobbed by his teammates. “That was my biggest personal thrill. It was a good, low-scoring game,” Spahn told reporters after the game. “I was glad it was over. Just imagine. Three hundred wins! Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson and now me. It seems almost immortal.”

Warren Spahn celebrated with Henry Aaron and catcher Joe Torre after securing his three hundredth career victory. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Spahn enjoyed another dominating August, going 6–0 as Charlie Dressen’s Braves won twenty of twenty-nine games. Climbing into third place, just six and a half games out with twenty-seven to play, the Braves still had a shot at the pennant. Following a 4–0 shutout pitched by Warren Spahn on September 2, Dressen was summoned to the front office, fully expecting a new contract. Instead, he was fired on the spot. “The general impression was that Dressen had lost control of the players, and I guess you’d have to say that was close to the truth,” Aaron remembered. “He’d lost their respect.”

Although many of the players weren’t fond of Dressen and his managerial style, they were even less impressed with the way the team handled his dismissal. “We finished the ballgame, walked into the clubhouse, and heard that John McHale was having a press conference up in the employees’ dining room on the second floor of the Stadium,” Mathews said. “Baseball can be a cold business.”

Charlie Dressen (next to Joe Adcock) was relieved of his managerial responsibilities on September 2, 1961. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The team replaced Dressen with its executive vice president. “Dressen did a good job,” Perini explained to reporters, “but Tebbetts was the man I wanted all along as my manager.”

Birdie Tebbetts was back in a major-league dugout after two years of sitting in meetings, negotiating the price of hot dogs at the ballpark, and deciding who would pave the stadium parking lot. “I wasn’t really happy there,” Tebbetts told reporters. “I found myself getting farther and farther away from the part of the game I love best.”

The ball club thought Tebbetts’s leadership on the field would help the Braves’ late-season pennant run. Instead, the team fizzled, going 12–13 down the stretch. “Tebbetts seemed like an odd choice for the Braves, first in the front office and then as manager, and I’m not the only one who thought so,” Eddie Mathews said. Suffering its worst season since leaving Boston, Milwaukee finished in fourth place at 83–71, ten games behind the pennant-winning Cincinnati Reds. “Nineteen sixty-one was the first year in a long time when we were never in the thick of the pennant race,” Mathews said. “We just could not get anything going or keep it going.”

Of greater concern to Braves officials was the declining attendance. After their pennant-winning seasons, the dip was steep with no bottom in sight: 1.7 million in 1959, 1.5 million in 1960, 1.1 million in 1961. Milwaukee’s fans had vehemently expressed their annoyance with the Braves’ performance and the County Stadium beer ban by simply staying away.

As Milwaukee’s new manager, Birdie Tebbetts was looked upon to rebuild the Braves into serious pennant contenders. (COURTESY MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, FRANK J. MARASCO CARTOON COLLECTION)