Lou Perini’s vision that Major League Baseball would expand into hungry metropolises far beyond the East Coast exploded into a baseball-wide revolution by 1962. In less than a decade, six of the original sixteen teams were playing in different cities. America’s Pastime had become a sport of franchises competing for financial gain. The Braves’ instant success in the untapped market of Milwaukee was directly responsible for the Browns moving to Baltimore in 1954, the Athletics going to Kansas City in 1955, and the Senators moving to Minnesota in 1961. The Braves’ impressive profits led Horace Stoneham to move the Giants to San Francisco and sent Walter O’Malley’s Dodgers to Los Angeles in 1958. Although critics feared that one of the sport’s foundations—the bond between a city and its baseball team—had been destroyed, the franchise relocations instead proved that America had an unquenched thirst for its favorite pastime, evidenced by shattered attendance records throughout both leagues. In addition, the success of the Braves’ relocation from Boston to Milwaukee was the catalyst for baseball’s newfound priority to operate as a profit-motivated big business.

In the weeks following the departure of the Dodgers and Giants to California, the clamor for major-league expansion grew into a contentious coast-to-coast roar. If cities that weren’t able to cajole one of the existing sixteen franchises—including Toronto, Atlanta, Denver, Houston, Dallas, and Minneapolis—couldn’t join Major League Baseball, they threatened to organize a third major circuit, the Continental League. To defuse this creation of a competing league, in 1961 the American League expanded from eight to ten teams with the addition of the Los Angeles Angels and the Washington Senators, and in 1962 the National League added the New York Metropolitans and Houston Colt .45s.

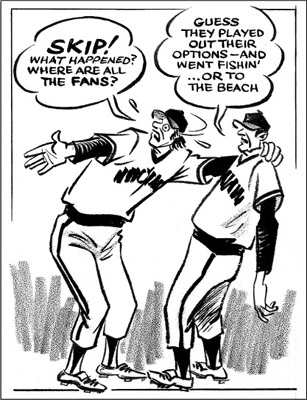

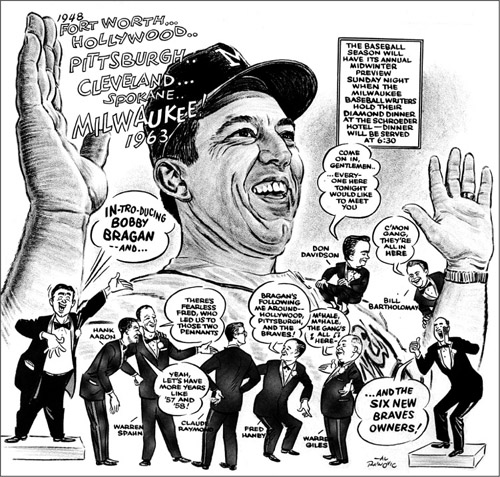

The early prognosis was grim for the Braves’ pennant hopes during their 1962 spring training camp. (COURTESY MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, FRANK J. MARASCO CARTOON COLLECTION)

With new teams and more contests, both leagues increased their traditional schedule of 154 games to 162 and pared down the number of games teams played against each other from 22 to 18. The once-rhythmic baseball schedule of four-game series was replaced with three-game series, and more games would be played under lights. Ultimately, expansion provided baseball owners eight additional dates to add to their bottom line.

Other cities wanted to reap major-league rewards. Nearly a thousand miles south of Milwaukee, Atlanta, Georgia, was growing into an urban metropolis complete with gleaming skyscrapers and snarled freeways. Using the blueprint Milwaukee had designed nearly a decade earlier, in 1961 newly elected Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr. promised to bring Major League Baseball to the South—even if he had to lure a team from elsewhere. “One of the planks in Allen’s platform … was the construction of a sports stadium,” author Furman Bisher recounted in Miracle in Atlanta. “[But] after [he] had been mayor for more than a year, Atlanta still sat there without a stadium and with no apparent motivation to get one started.”

Back in Milwaukee, owner Lou Perini—well aware that his team had lost much of its turnstile appeal—finally made an agreement with Milwaukee’s WTMJ television station to broadcast fifteen of the Braves’ 1962 road games. Baseball’s evolution into a big business was creating new revenue streams, and the hundreds of thousands of dollars the Braves would receive in sponsorship and advertising money offset Perini’s fears of television cutting into ticket revenues.

In Bradenton, Birdie Tebbetts, the once fiery and controversial manager of the rival Cincinnati Reds, looked to bring a less contentious atmosphere to the Braves clubhouse during spring training. Donald Davidson, recently promoted to traveling secretary, wrote later, “When Tebbetts joined the Braves as a vice-president and shifted to the dugout as manager in 1961, he ceased being a villain. Even the Braves who had despised him in Cincy liked him in Milwaukee. He was strict with the players, frequently leveling fines, but at the end of the season he’d take the money and pitched a party for the team, buying presents for the players.”

General manager John McHale, on the other hand, seemed ready to all but sacrifice the team’s future after having spent another off-season attempting to refurbish the Braves roster with savvy trades and signings. To acquire pitcher Bob Shaw from Kansas City, Milwaukee parted with three of its brightest prospects—Joe Azcue, Ed Charles, and Manny Jimenez—all of whom went on to have respectable major-league careers. In a lopsided trade with the Cubs, McHale gave up Bob Buhl—who went on to win twelve games for Chicago—for underachieving junk thrower Jack Curtis, who collected only four wins in 1962. Baseball’s expansion draft, held in the fall of 1961 to fill the new teams’ rosters, left the Braves with several of its players unprotected and available to fill the rosters of the newly formed New York Mets and Houston Colt .45s franchises. Felix Mantilla was lost to the Mets and was soon joined by Frank Thomas, who amassed thirty-four home runs and ninety-four runs batted in during the Mets’ hapless inaugural season. “There’s no telling what he’d have done if he’d been surrounded by the sluggers the Braves possessed,” Braves historian Gary Caruso said of Thomas’s potential in Milwaukee.

Crews from Milwaukee’s WTMJ-TV began televising road games during the 1962 season. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

The one position that benefited from the Braves’ youth movement was that of catcher. Uncertain whether Del Crandall would overcome the nagging injuries that hampered his throwing arm, the club looked to primary backups Joe Torre and Bob Uecker, a Milwaukeean who would become more famous for his comedic wit than his backstop skills. “I would be hailed as the first Milwaukee native to play for the Braves,” Bob Uecker wrote in his autobiography, Catcher in the Wry. “Later, I would be hailed as the first Milwaukee native to be traded by the Braves. Hometown boy makes good.”

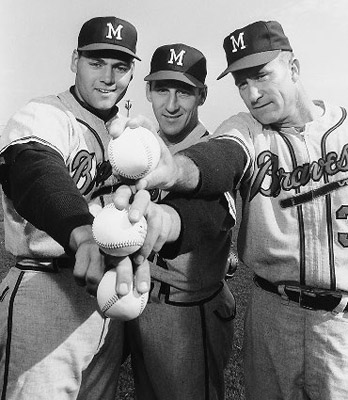

General manager John McHale acquired Bob Shaw (left) in hopes he could bring some youth to an aging pitching staff that still featured Warren Spahn and Lou Burdette. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Milwaukee native Bob Uecker joined an already talented Braves catching corps that featured Del Crandall and Joe Torre. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Artist Al Rainovic captured the fans’ growing disinterest in attending Braves games at County Stadium. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 271)

For the fifth year in a row, the Braves’ preseason ticket sales stalled. Whether fans were disgruntled over the County Stadium beer ban or the departure of crowd pleasers, they were no longer interested in going to the ballpark. “When I joined them,” Uecker confessed, “the Braves had declined from their World Series years, ’57 and ’58, and had become the one thing baseball fans can’t accept. A mediocre team. Not good enough to compete, not bad enough to be lovable.”

With a roster made up of aging superstars, inferior replacements, and underachieving prospects, the Braves started the season with a seven-game road trip—and dropped their first five games. By the time Warren Spahn took the mound for County Stadium’s home opener on April 18, the club had a pitiful 1–6 record. In the wake of the worst start in franchise history, Milwaukee hosted its smallest Opening Day turnout; only 30,001 watched the Braves rally for four runs in the bottom of the eighth to beat the Giants. The empty seats were a clear indication that the fans weren’t interested in the team’s efforts, and as the season progressed, crowds under 10,000 soon were the norm rather than the exception.

By May 9 Milwaukee sat nine games out of first in seventh place with a 10–14 record. The smallest crowd in County Stadium history, 3,673 stalwarts, sat in thirty-eight-degree weather to watch the Braves beat the Pirates. The next night Milwaukee dropped a 4–3 decision to Pittsburgh in front of only 2,746. “Every night at County Stadium, it was like playing in front of your closest friends,” Joe Torre said.

Relegated to a backup role with the return of Del Crandall, Torre seemed to be the only one benefiting from the early-season weather conditions. “I became a cold-weather catcher,” Torre admitted in his autobiography, Chasing the Dream. “If Tebbetts thought it was too cold to risk Crandall’s cranky shoulder, he’d start me instead.”

On the diamond, the Braves’ growing futility manifested itself against one of the worst teams in baseball history: the expansion New York Mets. Only four days after Tebbetts sold reliever Don McMahon to Houston because he felt the right-hander had lost his fastball, the Mets swept Milwaukee in a doubleheader, with both game-winning home runs coming in the ninth inning. Eight days later, the Mets swept another doubleheader at County Stadium after the Braves blew leads in both games. The Mets earned their sixth win in ten games against the Braves, 6–5, at the Polo Grounds on June 19. With a 17–45 record, they had more than one-third of their wins against Tebbets’s club.

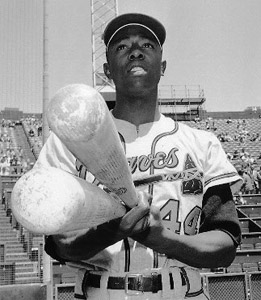

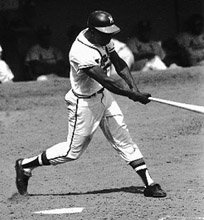

Led by Henry Aaron’s 45 round-trippers, the Braves feast-or-famine offense in 1962 finished with 181 home runs, good for second best in the National League. But their .252 batting average ranked a lowly eighth; only the expansion Colt .45s and Mets had lower averages. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

In Milwaukee, attendance continued to nosedive as the Braves dipped closer to the National League cellar. To lure fans, the ball club rescinded the beer carry-in ban on June 8, but that did little to boost long-term attendance figures.

Despite disappointing turnouts, Lou Perini publicy denied rumors that he was interested in selling the Braves. “Perini at that time hardly ever came to Milwaukee to see the ballclub,” third baseman Eddie Mathews remembered. “He just let McHale run the show while he tended to his construction business back east.” While insisting that the team wasn’t for sale, Perini placed 1.5 million shares of stock on the open market. “The ballplayers never paid much attention to any of that stuff, one way or the other,” Mathews said, “but we did notice something”: a group of businessmen who frequented County Stadium during the 1962 season. “These guys started showing up at our games, and that was when we were hearing all this happy crap about Perini wanting out.”

In June 1962 Milwaukee’s County Board once again permitted fans to carry beer into County Stadium. (COURTESY OF MIKE RODELL)

By the first All-Star Game, played in Washington, DC, on July 10, the Braves were 42–43, fourteen games behind the league leaders. Milwaukee was well represented, with Henry Aaron, Frank Bolling, Del Crandall, Eddie Mathews, Bob Shaw, and Warren Spahn on the National League roster. President John Kennedy threw out the first pitch before the Nationals pulled out an exciting 3–1 victory, with Bob Shaw earning the save. On July 30 the All-Star squads faced off again, this time in Wrigley Field, and the American League trumped the Nationals 9–4.

Following the year’s first All-Star Game, Milwaukee began to play respectable baseball as a resurgent Warren Spahn continued as the team’s anchor. “His snapping fastball was gone, but he could still beat them with his off-speed pitches and his control and his head,” Uecker wrote. After blasting his thirty-first career round-tripper on July 26 against the Mets to establish a National League record for most home runs hit by a pitcher, Spahn focused on becoming the winningest left-handed pitcher in baseball history.

Spahn took the mound against the Pittsburgh Pirates on September 29 as if it were just another game. But as the game entered the late innings, his unsmiling seriousness on the mound intensified. Merely cocking his head to one side while preparing for each pitch, the forty-one-year-old fed off the anxious Pirates hitters. “Sometimes I get behind on batters deliberately,” Spahn confessed. “Makes them hungry for fat pitches. I made a living on hungry hitters.”

Warren Spahn led the Braves pitching staff with eighteen wins in 1962 while posting a respectable 3.04 ERA and leading the league with twenty-two complete games. (COURTESY OF BOB BUEGE)

The Braves’ bats provided enough punch behind home runs from Joe Adcock and rookie Tommie Aaron as Spahn clinched his 327th career win with the 7–3 victory. Upon becoming the most successful left-hander in baseball history, the great southpaw credited his longevity with staying healthy. ‘‘I never went in the trainer’s room,” he explained. “I didn’t believe in icing my arm after a game. Ice is for mixed drinks, not your arm. All I’d do is go in the shower and let the hot water run down my arm.”

The Braves closed out the 1962 season the next day with an uninspired loss to Pittsburgh. Posting a respectable 86–76 record, the team nevertheless finished in fifth place, a distant fifteen and a half games behind the Giants. With their lowest winning percentage since arriving in Milwaukee, the Braves placed in the National League’s first division only because the Mets and Colt .45s had expanded the league to ten teams. Five days after the end of the 1962 season, Birdie Tebbetts abruptly resigned.

Two weeks later the Braves’ tumultuous off-season began when John McHale hired Bobby Bragan as the team’s next skipper. “Instead of a transfusion of young blood and fresh talent, we got a new manager with an ego problem,” Eddie Mathews said.

The most notorious incident behind Bragan’s boisterous reputation happened on July 31, 1957, in front of County Stadium fans. In the second unsuccessful year of his first big-league managing job for Pittsburgh, Bragan made an appeal play at second base, claiming Milwaukee base runner Bob Buhl had missed second base. “When the umpire ruled in the Braves’ favor, Bragan displayed his opinion by holding his nose. That prompted his ejection,” Gary Caruso recounted in The Braves Encyclopedia. Instead of walking off the field gracefully, Bragan paraded back onto the field, sipping an orange drink he had purchased from the stands. After offering a sip to umpire Frank Secory, he was ordered off the field. He then motioned as if to throw the drink into the umpire’s face. Only under threat of Pittsburgh’s forfeit of the game did Bragan finally leave the field. Two days after the incident, he was fired.

In 1962, Henry Aaron and his younger brother Tommie (right) established themselves in the major-league record books after the two homered in the same inning, a feat not performed since 1938 by the Waner brothers. (WHI IMAGE ID 49387)

Despite being a former major-league catcher, Braves manager Birdie Tebbetts struggled with a pitching staff that didn’t post a twenty-game winner for the first time since 1955, and a bullpen that lost thirty-two one-run games in 1962. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Even with a new manager in place, Lou Perini saw a bleak future for the franchise. Although he had reaped $7.5 million in profits during his first nine years in Milwaukee, the Braves owner posted his first losses in 1962. The fans were avoiding County Stadium in record numbers, and the team’s total 1962 attendance of 766,921 had them finishing ninth out of ten National League clubs—a 30 percent decline from the previous year. Perini decided it was time to get out of the baseball business.

The Braves’ once-royal robe was in need of refurbishment by the end of the 1962 season. (COURTESY MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, FRANK J. MARASCO CARTOON COLLECTION)

On November 16, 1962, Lou Perini and his Perini Corporation, which had held controlling interest in the team since 1944, sold the Milwaukee Braves to the LaSalle Corporation, a group of prominent Chicago-area businessmen led by thirty-four-year-old insurance broker William Bartholomay. At a press conference Lou Perini enthusiastically introduced the new owners as “young sportsmen who are more interested in winning a pennant than in financial returns.” But former Milwaukee Brewers owner and Perini rival Bill Veeck sensed, “The whole deal had the uncomfortable smell of city slickers coming in to take over.” Milwaukee Journal sports editor Oliver Kuechle soon dubbed the new owners “The Rover Boys,” possibly after an early 1900s children’s book series featuring three mischievous brothers.

Lou Perini (left) enthusiastically introduced the Braves’ new ownership group at a press conference. (COURTESY OF BOB BUEGE)

Bartholomay and his partners were heirs to the family fortunes of Johnson’s Floor Wax, Searle Pharmaceuticals, the Miller Brewing Company, and Chicago’s Palmer House. They had focused their efforts on Milwaukee after an unsuccessful attempt to purchase the Chicago White Sox a few years earlier.

Introductions were in order after the Braves’ ownership and field general changed during the off-season. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 41)

During the early months of 1963, few certificates were issued during the Braves stock drive. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Purchasing all but 10 percent of the Braves for $6,218,480, the Braves’ new owners had a $2 million balloon payment due in 1968. Desperate to generate a new revenue stream and eliminate fears of absentee ownership, Bartholomay and his associates offered to sell 115,000 shares of team stock at a price of ten dollars per share to Wisconsin residents before the 1963 season. The new owners hoped the stock sale would not only pull the team back above the financial break-even point but also reinvigorate fan interest. The invitation to Milwaukee buyers was widely advertised—and largely ignored. “If there had been a market for it, the club would probably still be in Milwaukee,” Donald Davidson concluded, “but the golden years were over and the team was no longer winning pennants.”

By April 7 only thirteen thousand shares had been sold to just sixteen hundred new investors. The stock offering was deemed a bust and was withdrawn. Followed by a preseason ticket sales push that exposed the community’s local apathy with even fewer season tickets sold than in years prior, the rookie owners sensed they had bought into a grave situation. Citing the failed stock sale, Bartholomay’s ownership group claimed Milwaukee no longer wanted the Braves. They immediately began looking for a new, more hospitable venue for their franchise. “We never considered the possibility of the Braves leaving town,” Henry Aaron said. “But the Miracle of Milwaukee, like hula hoops and ducktail haircuts, had been left behind in the fifties.”

♦ ♦ ♦

With the new ownership syndicate overseeing his personnel moves, newly promoted president and general manager John McHale (seated) continued to dismantle the Braves’ aging roster prior to the start of the 1963 season. (COURTESY OF BOB BUEGE)

During the off-season, newly promoted president and general manager John McHale continued dismantling the team’s aging roster, including sending Joe Adcock to Cleveland. “A Braves fan returning to County Stadium after, say, a four-year absence would have been hard-pressed to identify the Milwaukee players,” baseball historian Bob Buege said in The Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy. “Fortunately for that fan and others like him, the Braves began wearing their names on the back of their uniforms in 1963.” The extensive roster turnover, along with jersey alterations that included the elimination of the tomahawk, made fans feel management was attempting to generate a new team identity in the wake of the ownership change.

The Braves also abandoned their traditional Bradenton, Florida, spring training facilities for a new state-of-the-art facility across the state in West Palm Beach. “Mr. Perini was in the process of building up an entire side of the city—I remember him taking me around in his car and telling me what he was going to do with all that swampland—and a major part of the development was a new spring facility for the Braves,” Henry Aaron recalled in his autobiography I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story. According to Aaron, when Perini sold the Braves to the LaSalle Corporation, “part of the deal was that the team would train on his swampland.”

The new facility included one full diamond and an additional half field for infield work, all providing skipper Bobby Bragan the perfect arena for molding the Braves into winners. “From the first day Bobby arrived, he was going to do things his own way,” Aaron said.

Bragan often lashed out in frustration at his team of veterans on the decline. “He could really get on your case. He had a way of talking out of the side of his mouth, like Humphrey Bogart, and he could dust you off equally well with a sarcastic line or with your basic seaman’s vocabulary,” Bob Uecker recalled.

With pressure from management to quickly rebuild the team into a winner, the Braves’ new manager was decisive about who would make it out of spring training. “We had the feeling Bobby Bragan was there as a hatchet man,” Warren Spahn said. “Getting rid of veterans was his role.”

Pitcher Carl Willey was the first big name jettisoned at the end of camp, when he was sent to the Mets. Soon after, Bragan focused on the Braves’ backstop dilemma. “When the ’63 season began, Del Crandall was still first-string catcher,” Bragan recounted in his autobiography, You Can’t Hit the Ball with the Bat on Your Shoulder. “He’d had many great years with the Braves, a good handler of pitchers who handled the bat well enough to hit second in the lineup—rare for a catcher, but it quickly became clear in ’63 that Joe Torre was simply younger and better than Del.” By the end of spring training, Bragan had made Torre his starting catcher.

By then Bragan’s unyielding ego had already created strained relationships with several of the veterans. “Bobby probably knew as much baseball as any of the Braves managers, but he had difficulty communicating with players. Bragan, as a manager, was a complex man,” Donald Davidson wrote.

As controversial as he was stubborn, Bragan often made decisions based on emotion. “I’m sure I would have been a better manager if I hadn’t been influenced by a ballplayer’s personality,” he said years later. “Players’ attitudes and off-the-field habits sometimes affected my treatment of them.” With the Braves scheduled to open the season on the road in Pittsburgh, Bragan assigned the honorary Opening Day pitching duties to Lou Burdette instead of Warren Spahn. “I’d like to think I let Lou pitch the first game because he’d been so outstanding during spring training, but the truth is I probably felt he deserved the honor over Spahn because of their difference in attitude,” he confessed. “Warren Spahn’s single interest was Warren Spahn.”

Burdette and the Braves couldn’t get the job done in Pittsburgh, and they started the season winless at 0–2. Only 26,120 fans were at County Stadium’s home opener on April 11 to behold Warren Spahn’s dominance of the Mets. Except for a Duke Snider home run, no Met got past second base during the Braves’ 6–1 victory. “Despite the fact that the team was falling apart around him, old Hooks was as good as ever in 1963,” Henry Aaron proclaimed.

Following Spahn’s 328th career victory, Bragan’s Braves continued to streak their way through April. A four-game losing streak followed a seven-game winning streak, and Milwaukee finished the month with a 12–8 record, good for third place and only two and a half games out of first. Bragan seemed to have assembled a solid combination of veterans and youth, all of them hungry to capture another pennant. “In ’63 I was having a great time,” rookie infielder Denis Menke fondly recalled. “I was glad I was breaking into the major leagues with guys like Spahn and Mathews and Crandall. That season we used to have team parties and everyone would be there.”

Bobby Bragan’s complex approach to managing baseball games left many of the Braves frustrated, confused, or bored during moments of instruction. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Meanwhile, nearly eight hundred miles south of Milwaukee, Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr. continued his quest for a major-league franchise. When disgruntled Kansas City Athletics owner Charlie Finley came to Atlanta on April 25, Allen looked to entice him to move his franchise south. The mayor’s tour through the “Heart of the South” led them to a pile of rubble near the Georgia state capitol, less than a mile from Atlanta’s downtown district. According to Furman Bisher in Miracle in Atlanta: The Atlanta Braves Story, Mayor Allen gushed: “Just like I told you, Mr. Finley. The greatest site for a sports stadium in America.” Finley replied, “I can almost hear the crack of the bat. You build a stadium here, and I guarantee you Atlanta will get a major league franchise.” With that brief exchange, Allen had created the momentum necessary for the city to build a major-league-caliber stadium on speculation.

Back in Milwaukee, the Braves’ promising season quickly began to disintegrate. Finishing May in eighth place, Milwaukee was five games under .500 and eight and a half games out of first. Only the hapless Colt .45s and Mets kept them out of the National League cellar. With the team struggling, John McHale decided Lou Burdette was on the downside of his career and deemed him expendable. After thirteen seasons and 173 wins in Braves flannels, the man radio announcer Earl Gillespie called Loober was dealt to the Cardinals—along with his unsubstantiated pitching secrets. “Burdette never told me or anybody else on the team what substance he used or where he stashed it when he threw his illegal pitch,” Joe Torre speculated in his memoir, Chasing the Dream. “He knew if he told a teammate about his secret and that person was traded, the word would be all over the league.”

Burdette’s departure marked the end of his pitching duo with Spahn, a combination that had produced 443 victories for the Braves. And it left the team with even fewer familiar faces on the bench. “With Buhl and now Old Nitro leaving as well, I was starting to feel like a stranger on my own ball club,” Mathews said in Eddie Mathews and the National Pastime. “The only ones left from the old days were Spahnie and I and Crandall, and of course Aaron.”

As the last of the Braves aces from the team’s championship years, Spahn was left to lead a staff of young hurlers expected to quickly develop into winners. Denny Lemaster, Bob Hendley, Tony Cloninger, Claude Raymond, and Bob Sadowski all showed natural ability but lacked the consistency that had symbolized Milwaukee’s hurlers during their glory years. It was no surprise, then, that on July 2, Spahn was given the task of facing Juan Marichal during another inclement evening in San Francisco.

Just 15,921 fans braved the San Francisco chill to witness what would become one of the last truly great heavyweight pitching matchups in baseball history with both hurlers going the distance in a baseball marathon for the ages. Marichal, the Giants’ twenty-five-year-old right-hander, and Spahn, the forty-two-year-old Braves southpaw, cut through their opposing lineups inning after inning, leaving little behind on the base paths. As the innings mounted, the scoring opportunities withered. The game remained scoreless as it marched into extra innings. Finally, in the bottom of the sixteenth, the odds caught up with Spahn, who until now had kept Willie Mays hitless. With one out, Mays sent one of Spahn’s trademark screwballs into the night to defeat the Braves 1–0. In a remarkable feat of stamina, both pitchers went the distance, as Marichal allowed just eight hits in sixteen innings and struck out ten while Spahn gave up nine hits in fifteen and one-third innings. “Both pitchers threw over 200 pitches. Can you imagine any pitcher going sixteen innings anymore?” Mathews pondered nearly thirty years later. “And what about the catcher? Del Crandall worked that whole game.”

The Braves’ John McHale with 1963 All-Star Game representatives Joe Torre and Warren Spahn (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The outcome of the epic pitching duel was just one of many disappointments during the first half of the season, and the Braves found themselves seven games behind the first-place Dodgers at 43–40 by the All-Star break.

After four years of complaints from both players and fans, Major League Baseball returned to its original single-game format in Cleveland for the 1963 All-Star contest. For the July 9 game played at Municipal Stadium, Henry Aaron started in the outfield, while Warren Spahn and Joe Torre took in the festivities from the bench, as the National League held on for a 5–3 victory.

While the All-Star Game was always considered a celebration of baseball’s elite players, off the diamond club executives often used the annual event as an opportunity to schmooze and conduct baseball business. In 1963 Mayor Ivan Allen and his Atlanta contingent used the platform to introduce their city to potential major-league owners. When talks with Charlie Finley of Kansas City stalled, the Atlanta group was desperate for a stadium tenant. Allen quickly arranged a lunch meeting with some of Milwaukee’s Rover Boys. By the end of that fateful meeting on July 9, negotiations between Atlanta and the Braves had begun.

Bill Bartholomay (sitting) and John McHale (standing) (COURTESY OF BOB BUEGE)

Less than two weeks later, the first news linking Atlanta with the Braves leaked. Minutes from the Atlanta Stadium Authority’s July 15, 1963, meeting revealed that officials had “discussed briefly the events leading up to an expression of interest in Atlanta by a club other than Kansas City” during their junket in Cleveland. Soon after, sportswriter Bob Broeg predicted in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that if attendance didn’t improve in Milwaukee, the Braves would leave for Atlanta. In the first of a series of disconnected denials, team executives did little to dispel the rumors. “We didn’t buy the franchise to move to Atlanta,” Bartholomay quipped to reporters. “How do these rumors get started?”

Having secured the RBI crown with 130 and connecting for his forty-fourth home run to tie Willie McCovey for the league lead, Henry Aaron almost achieved baseball’s triple crown in 1963—but he finished third in the batting race with a .319 average (behind Tommy Davis at .326 and Roberto Clemente at .320). (WHI IMAGE ID 26390)

As Bartholomay continued to deny the rumors in newspapers and on the radio, he spent the next six weeks meeting with various National League owners looking for an answer to the hypothetical question, “If we decided to move the Braves to, say, Atlanta, Georgia, could we count on your vote?”

While their potential franchise move was discussed in boardrooms and baseball executive offices, the Braves flirted with the .500 mark throughout July and August. Warren Spahn continued to rack up career records and ignore any signs he was getting older. On August 13 he not only started his 601st game, breaking Grover Cleveland Alexander’s National League record, he also whiffed five Dodgers, raising his career total to 2,383 strikeouts and making him the all-time left-handed strikeout leader. “I think part of what kept that flame burning inside Spahnie was the fact that he felt he had no time to lose,” Uecker remembered.

Braves officials sent a confidential memorandum to Atlanta’s Stadium Authority on September 4, outlining their interest and requirements to move the Braves to Georgia. Approximately two weeks later a deal in principle was reached to move the team in time for the 1965 season. While a move had not yet been announced publicly, the city of Milwaukee knew the team owners were unhappy, and several prominent Milwaukee businessmen and city officials arranged a private meeting with Bill Bartholomay, John McHale, and Braves executive vice president Tom Reynolds one night in mid-September 1963. As the head of the community group trying to keep the Braves in Milwaukee, influential industrialist Edmund Fitzgerald asked Braves leaders outright, “What do you want? What kind of help can we give you? What will it take to make you happy here in Milwaukee?”

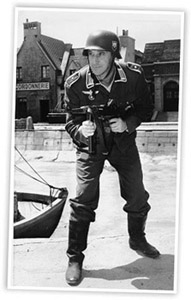

The same day he set the all-time left-handed strikeout record, Warren Spahn filmed a cameo as a German soldier for the television series Combat! Spahn had received the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart serving in the U.S. Army during World War II and was the only major-league ballplayer to earn a battlefield commission during the war as a second lieutenant. He later said, “I matured a lot in those three years in the army… . If I had not had that maturity, perhaps I never would have pitched until I was almost 45.” (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Bartholomay, Reynolds, and McHale played their cards close to their vests, often mentioning the team’s poor attendance as a reason for considering relocating the franchise. Carefully avoiding any legal traps by entering into agreements they had no intention of honoring, they discussed the attributes of San Diego and Seattle as possible suitors for the team, but they never mentioned Atlanta. Hoping to appease the disgruntled owners, Fitzgerald’s group agreed to spearhead a “Go to Bat for the Braves” campaign to help boost season ticket sales to 7,500 seats and secure a $550,000 deal for radio and television rights—amounts established by Bartholomay, McHale, and Reynolds. With that, the Rover Boys had acquired the leverage they needed to finalize negotiations with Atlanta.

The “Go to Bat for the Braves” campaign was led by Edmund Fitzgerald (left) and Allan H. “Bud” Selig (right), joined here by Judge Robert Cannon (far left) and Eddie Mathews. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

The Braves’ future looked promising in 1963 with an influx of young arms including Wade Blasingame, Denny Lemaster, Hank Fischer, Bob Sadowski, and Tony Cloninger. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

To generate interest in season tickets, Johnny Logan, Denis Menke, Bobby Bragan, Henry Aaron, Edmund Fitzgerald, Del Crandall, and John McHale participated in numerous “Go to Bat for the Braves” luncheons during the off-season. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Bill Bartholomay criticized Milwaukee’s “baseball climate,” despite the Braves outdrawing the Cubs during ten of the previous twelve seasons and averaging 94.4 tickets sold per 100 residents each year, compared to an average of 22.2 for other National League cities and 20.7 for American League cities over the same period. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Meanwhile, Bobby Bragan’s first year with the Braves found the team finishing with an 84–78 record and a .519 winning percentage, their worst since moving to Milwaukee. Losing thirty-one games by one run, the Braves slipped into sixth place in the ten-team league. “Pitching was our downfall,” Bragan claimed. “But I was firmly convinced [Denny] Lemaster and [Tony] Cloninger were the key to Milwaukee’s future, a potential lefty-righty combination to replace Spahn-Burdette. One more good season from Spahnie and then the kids would be able to carry the pitching load themselves.”

Only 773,018 fans visited County Stadium in 1963, and rumors of the team’s exodus intensified. The whispers were so persistent that John McHale issued a cryptic statement: “The Braves will be in Milwaukee, today, tomorrow, next year and as long as we are welcome.” Still, after the “Go to Bat for the Braves” campaign sold fewer than four thousand advance season tickets, the Braves’ owners concluded that the city was no longer interested in reinvigorating the franchise. “When we began to look around and inquire about results in late January,” Tom Reynolds recounted to Furman Bisher in Miracle in Atlanta: The Atlanta Braves Story, “we got a lot of blank stares. We were going out to dinners and making appearances and eating a lot of chicken pot pie, but about all we were getting out of it was a bellyful of chicken pot pie. We weren’t getting any results. In short, these people, for all their good intentions and promises, were falling flat on their faces.”

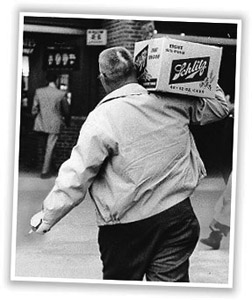

Even more discouraging, the “Go to Bat for the Braves” committee secured only a $400,000 offer for the Braves’ broadcast rights for the upcoming season, well short of their $550,000 goal. In the current offer, from the Schlitz Brewing Company, it almost felt like television rights were thrown in for good measure, since for radio alone the offer had been $375,000 the two previous years. On the heels of the failed “Go to Bat for the Braves” campaign, Braves executives reconnected with Atlanta’s officials.

Meeting at the O’Hare Inn in early February, Bartholomay and the Braves promised to play in Atlanta if a major-league-caliber stadium was available to host them for the 1965 season. Although the men walked out of the meeting with a twenty-five-year contract between the Braves and the city, no press conference was called or media release drafted. Instead, with the deal in hand, Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr. leaked a story to the Atlanta Constitution on March 5 insinuating that an unnamed major-league franchise had committed to relocating to Georgia in 1965 if a stadium could be built in time. The next day Atlanta officials approved funding for an $18 million state-of-the-art stadium; on April 15 the ceremonial groundbreaking for Atlanta Stadium took place. All the while, Braves officials issued denials. “We are positively not moving,” Bartholomay proclaimed to reporters during the off-season. “We’re playing in Milwaukee, whether you’re talking 1964, 1965 or 1975.”

♦ ♦ ♦

Despite an uncertain future, the Braves continued preparing for the 1964 season in Milwaukee. John McHale spent another busy off-season shedding the team’s aging superstars, sending Del Crandall to San Francisco for an often-injured Felipe Alou. “Because of the magnitude of the names involved, the success of the Braves in the 1950s and the lack of same in the ’60s, these deals don’t look particularly good on McHale’s resume,” Gary Caruso said in The Braves Encylopedia. “While none of the nine key players ever again approached the level of success they had with the Braves, in hindsight it was obvious McHale was late in pulling the trigger and seldom got much for the team’s former stars.”

An optimistic Bobby Bragan thought his team had rebuilt itself to the point of serious contention. “I truly believed 1964 could be the season I’d manage a major league club to a pennant,” he recalled. “The Braves had that famous nucleus returning—Aaron, Mathews, Spahn—with our promising pitchers ready to live up to their potential. When I matched my starting lineup player-for-player with that of any other team in the National League, I felt we had the edge”

With the off-season departure of Del Crandall, Braves manager Bobby Bragan (standing) relied on his revamped catching corps of (from left to right) Gene Oliver, Ed Bailey, and Bob Uecker. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

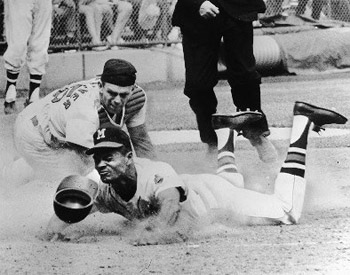

Felipe Alou (avoiding a tag by Cardinals catcher Tim McCarver) brought speed to the Braves’ potent 1964 lineup. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

Tapped to pitch for the Braves’ season opener in San Francisco was forty-three-year-old Warren Spahn, looking to repeat his previous season’s performance of hurling twenty-three wins. “What a hell of a way to end a career as a pitcher,” Eddie Mathews wrote. “He wouldn’t do it, though. He’s been one of my closest friends, but he’s a proud man. He still thought he could go right on pitching. Actually, I don’t think his arm ever recovered from that 16-inning game against Marichal.”

Once the game entered the late innings, Spahn faded and the Giants pulled away for an 8–4 victory. It was the first of a seven-game road trip that found the Braves at 4–3 by the time they arrived in Milwaukee for their home opener. With a crowd of 38,693 at County Stadium looking on, the Braves’ Denny Lemaster couldn’t survive the third inning and was tagged for five runs in an eventual 8–6 loss to the Giants. More disturbing was an uncharacteristic wave of vandalism during the game as fans tore down poles and wires around the stadium. Fifteen juveniles, two carrying knives, were picked up for throwing debris, spitting on people, and fighting among themselves. Nine bleacher occupants stormed onto the field, attempting to shake players’ hands. Another fan slid into second base during the game. One hoodlum was thrown out for hurling debris onto the field, only to return to continue throwing beer bottles and cans. Two adults were arrested for public drunkenness, and a group of teenage girls were roughed up by another group of teenagers. Local police considered the disturbances “the worst in our experience.” It was further evidence that attending baseball games at County Stadium was no longer considered an “event” and that local apathy was only getting worse as relocation rumors swirled.

As the 1964 season began, Warren Spahn looked to continue defying the encroaching effects of age on his body. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 257)

Milwaukee continued to exchange wins and losses throughout April and finished the month at 8–6. As late as May 5 the Braves were in second place, just a game out of first, but they stumbled through a mediocre May and the first half of June. “There were many losses during those early months of the season and we had to labor hard to stay in the first division,” Felipe Alou admitted in his autobiography.

On May 5, 1964, Warren Spahn blanked the Mets on four hits, earning him the distinction of having shut out every opposing National League team at least once in his career. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

On June 22, 1964, Bill Bartholomay (left) and John McHale (far right) announced they had renewed manager Bobby Bragan’s contract for the 1965 season. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

Hoping to find the right combination to exploit the Braves’ potent offense, Bragan started twenty-nine different lineup configurations through the end of May. “On the field, Bragan liked to experiment,” Donald Davidson acknowledged. “He was also one of the first managers not to bat the pitcher ninth. Bobby had figures to prove all his theories.”

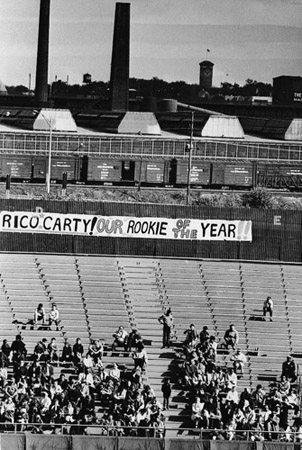

The notorious lineup juggler frequently had Eddie Mathews bat leadoff to make room for one of the Braves’ youngest rising sluggers, Rico Carty, a Dominican Republic native who called himself Beeg Boy. According to Henry Aaron, Carty “didn’t speak much English and needed someone to take him under his wing when he came up, so I roomed with him his rookie year.” The Braves’ newest slugging sensation soon caught the imaginations of County Stadium fans, who plastered the bleachers with signboards that read, Go, Rico, Go; You Can Have Ringo, We Have Rico; and Rico for President. Despite Carty’s abundance of talent and ability to hit thirty-five to forty home runs a year, Aaron remarked years later, “He was one of the most gifted hitters I’ve ever seen but he didn’t use those skills to the fullest.”

Left fielder Rico Carty connected for twenty-two home runs and hit an impressive .330 batting average during his rookie campaign with the Braves. (ALL-AMERICAN SPORTS, LLC)

Often Carty’s temper matched his talent. “Rico simply did whatever he wanted whenever he wanted, and the wishes of others didn’t merit his consideration,” Bragan said. “Once he even got into a fight with Hank Aaron during a flight, and Hank Aaron was the most easygoing man anybody ever met.”

The sparse bleacher crowds at County Stadium did their best to support the Braves’ newest rookie sensation in 1964. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

This left Bragan in the precarious position of trying to manage the rookie left fielder’s personality while getting him to produce in the everyday lineup. “[Rico] didn’t take things as seriously as he should have. But he was so temperamental and so talented, Bragan had to either take it a little easier on him or run him off, and the team was better off with Rico than without him,” said future Braves pitcher Billy O’Dell.

But the infusion of Carty’s power couldn’t compensate for the team’s depleted pitching staff. Although Denny Lemaster posted a respectable 8–6 record through the Fourth of July, Tony Cloninger was stuck at 7–7, Bob Sadowski floundered at 3–6, and Warren Spahn had to endure a 5–8 record. By the All-Star break the Braves’ 38–40 record already had them ten and a half games behind the first-place Philadelphia Phillies. “The National League was turning over in those years,” Henry Aaron explained, “and it was turning over on the Braves. We didn’t have the speed that the Dodgers and Cardinals had, and when Spahn finally lost it, we couldn’t match Koufax or [Bob] Gibson [of the St. Louis Cardinals].”

When baseball’s elite gathered at New York’s Shea Stadium on July 7 for the 1964 All-Star Game, a recent article in The Sporting News had sportswriters and baseball officials chattering among themselves on elevators, in press quarters, and in smoke-filled rooms. The story, attributed to an “unimpeachable source,” claimed that the Braves planned to move to Atlanta in 1965, and the national media ran with the revelation. The Braves’ All-Star representatives, Henry Aaron and starting catcher Joe Torre, were hounded by the press. In an attempt to lighten the situation, Torre hammed it up the day of the game by pasting a felt “A” onto his baseball cap. Even after the National League pulled out an exciting ninth-inning rally for a 7–4 victory, it seemed the only thing the national media could focus on was the franchise that was about to abandon Milwaukee. “For me this was a lot different than the move from Boston,” Eddie Mathews said. “I never had any roots in Boston, and most of us were young guys then. Now my family lived in the Milwaukee area. I liked Atlanta, and I had friends there, but I sure as hell didn’t want to move there.”

Following the All-Star Game, The Sporting News and the New York Times confirmed that the Braves would play the next year in Atlanta. Team officials continued to issue murky denials. “This rumor … has gone full circle,” John McHale waffled to reporters all season long. “How many times do we have to keep answering?”

Despite the drama unfolding in the newspapers, the Braves began to turn their season around. Winning sixteen of twenty-four games through the first of August, they shortened their deficit behind the first-place Phillies to six and a half games. By late August, Cloninger and Lemaster were having fine seasons—Cloninger ended up winning nineteen games, and Lemaster got seventeen victories—but the rest of the Braves starters had the habit of giving up one more run than the team could score.

In the clubhouse, morale stayed strong despite the possibility of the team relocating. “In 1964 we still had that great camaraderie, and the reason was we were still a winning ball club, still in contention all the time,” Lemaster remembered. “And in that season Spahn and Bragan were always in each other’s face.”

Although he had signed an $85,000 contract prior to the 1964 season, making him the highest-paid pitcher in baseball, Warren Spahn had finally started giving in to age. The southpaw’s ERA had more than doubled from the previous year, and after his nearly five thousand innings of work in the big leagues, Bragan dropped him from the starting rotation. “We should have been expecting it,” Aaron admitted. “He finally hit the wall in 1964. He still looked like himself, with the fancy windup and the big leg kick, but there was nothing left on the ball.”

Looking for a graceful way to transition the veteran out of uniform, Bragan demoted a disgruntled Spahn to the bullpen. “During the ’64 season my relationship with Warren Spahn completely soured,” Bragan wrote. “There was no question why we weren’t getting along.”

Spahn was determined to continue pitching, regardless of Bragan’s reassignment. “If an athlete’s ego won’t let him accept the fact that it’s time to retire, that’s where the problem comes in,” Mathews wrote. “Spahnie pitched a few more good games, but mostly he got hit hard. It hurt me—it hurt all of his teammates—to watch him getting knocked around like that. He deserved a better finish.”

Returning to the starting rotation for a couple of late-season starts with little success, Spahn failed to win more games than he lost for the first time since 1952, finishing with a 6–13 record. “The sad part about it was that we might have won the pennant in 1964 if he’d been even a shadow of the old Spahn,” Aaron speculated. But time had finally caught up to Spahn. In November, the future Hall of Famer was granted his wish to pitch elsewhere and was sold to the Mets. “Spahn had every chance to stay with the Braves, first as one of the team radio broadcasters, then as a roving pitching coach,” Aaron recalled. “I think the Braves were fair with Spahn. I think he blew it himself. His record the next season with the Giants and Mets proved the Braves were right.”

Behind center fielder Lee Maye (sliding into third base), who led the senior circuit in doubles, Milwaukee in 1964 featured five players with twenty or more home runs and led the National League in runs, doubles, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage, while their batting average of .272 was tied for the league’s best. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

But before Spahn turned in his Milwaukee flannels, the Braves finished their 1964 season at County Stadium against the Pirates. “For the last game of the year, Bragan decided it would be a clever idea to have me manage the team while he sat in the stands and watched,” veteran third baseman Mathews recalled. The unique situation provided Mathews not only his first taste of being a major-league skipper but also an opportunity to take advantage of the magnitude of the situation: “For all we knew, this was going to be the Braves’ final game in Milwaukee. We were winning going into the ninth inning, 6–0. I decided to put Hank and myself into the game for the last inning, along with a few other veterans, just to give the fans one last chance to see us. I also took out the pitcher, Bob Sadowski, even though he was pitching a shutout, and put in Warren Spahn to finish the game. He hadn’t won a game in three months, but if we were leaving, who else would you want as the last Braves pitcher? The fans gave him a huge ovation.”

After amassing 356 career victories, 2,493 strikeouts, and 5,046 innings during 714 pitching appearances for the Braves, Warren Spahn was sold to the New York Mets on November 23, 1964. (ROBERT KOEHLER COLLECTION)

The Braves’ 6–0 victory over the Pirates was bittersweet, the culmination of a September streak that saw the team gain nine games on first place. The Braves finished the season with an 88–74 record. “We didn’t really start to play ball until the last couple weeks of the season. We won 13 of our last 15 games and made up a lot of ground, but the best we could do was finish five games back,” Mathews said regretfully.

Although the Braves never seriously contended for the pennant in 1964, attendance at County Stadium increased slightly to 910,911. But only 36,000 Milwaukeeans attended the final six home games, one more sign that fans were disgusted with the team’s continued denials of a relocation to Atlanta.

As the season wound down, Bartholomay continued to dismiss the rumors publicly but privately avoided committing to any sort of a future in Milwaukee. When Milwaukee County officials offered to renegotiate the Braves’ stadium lease—suggesting an annual rent of one dollar up to the first million admissions, along with a new deal on concessions and maintenance that would save the Braves an additional $120,000 a year—the Braves’ owners declined, claiming to be fully satisfied with their existing lease. In September Schlitz Brewing Company offered a three-year broadcast sponsorship deal that represented a 33 percent increase over the team’s existing contract; Bartholomay also turned it down. Just ten days after telling the press that it would be a personal disappointment to leave Milwaukee, Bartholomay scheduled a press conference.

Following a meeting of National League officials and club owners to discuss plans for the Braves’ transfer from Milwaukee to Atlanta, National League president Warren Giles was flanked by John McHale (left) and Bill Bartholomay (right) during a press conference. (DAVID KLUG COLLECTION)

On the afternoon of October 21, 1964, an army of television and radio press anxiously waited inside an improvised pressroom at Chicago’s Ambassador East Hotel. At 1:50 p.m., Milwaukee Braves publicity director and former relief pitcher Ernie Johnson entered the room with a press release in hand and confirmed the rumors: “The board of directors of the Milwaukee Braves, Inc., voted today to request the permission of the National League to transfer their franchise to Atlanta, Georgia, for 1965.”

The same Braves franchise that in 1953 had become the first club in fifty years to relocate would become the first club to switch cities twice. And for the first time, a city was about to be stripped altogether of its major-league status. While the forsaken fans of the Boston Braves, St. Louis Browns, Brooklyn Dodgers, New York Giants, and Washington Senators had lost teams to relocation, they had the option to transfer their allegiances to the other major-league team across town. The Milwaukee fans immediately lashed out at the Braves’ owners not only for their desertion but also for their conscious deception. Their anger was summarized in a third-grader’s crayoned note sent to Bartholomay that proclaimed: “YOU ARE A LIAR.”

Milwaukee still had a legal trump card to play, because the Braves’ stadium lease ran through 1965. After paying $200,000 in rent during the 1964 season, Bartholomay assumed that the county would accept a $500,000 cash settlement to buy out the contract’s final year. Instead, the county board voted unanimously to reject the offer and authorized counsel to incur any expense necessary to keep the Braves in town. Accusing the Braves of antitrust violations, Milwaukee County filed suit. “Milwaukee politicians who hadn’t seen the Braves in years suddenly became devout fans,” Donald Davidson remembered in Caught Short. “Bartholomay, John McHale, part owner and general manager, and the other owners were unjustly and hostilely accused of being money-minded carpetbaggers.” The animosity grew so heated that public officials claimed the team had sabotaged the season to make the city look bad. According to Davidson, “Eugene Grobschmidt, outspoken chairman of the Milwaukee County Board, actually accused Bragan and the Braves of purposely losing games,” citing Bragan’s 110 different starting lineups as proof.

After Milwaukee’s tumultuous 1964 season, Braves pitcher and Oshkosh, Wisconsin, native Billy Hoeft claimed to a reporter that manager Bobby Bragan tried to lose games by regularly switching around the team’s lineup. (ALL-AMERICAN SPORTS, LLC)

Grobschmidt convinced board members to call for an investigation of Braves management’s possible contract violations in ticket sales practices and “apparent ineptitude.” The County Board further reasoned that a championship would have made it impossible to justify the Braves’ departure for Atlanta. “That, of course, was ridiculous,” Eddie Mathews said. “Despite what Bragan’s ego seemed to believe, it was the ballplayers, not the manager, who won or lost games. Bragan did his thing, right or wrong, but there’s no way he was ever trying to lose. Absolutely not. He’s not that kind of person. He could be very sarcastic, and quite honestly I didn’t think he was a good manager, but as far as losing on purpose—no way in hell.”

(From left to right) Milwaukee County Board chairman Eugene Grobschmidt, county executive John Doyne, and Milwaukee Sentinel sports editor Lloyd Larsen held a press conference at General Mitchell Field upon returning from a meeting with National League owners. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Undaunted by the pending lawsuit and proposed inquiry, team officials began transferring operations to rented offices in Atlanta during the off-season. About two weeks after the Braves’ owners officially announced their intentions, the National League gave the team permission to move to Atlanta, but not until 1966. That left Milwaukee with one last, sad summer to either save their Braves franchise or prepare to be the first city abandoned by big-league sports. “For the players—and the fans—it was horrible to see our team and our city going at each other in court, like a messy, bitter divorce,” Henry Aaron remembered. “We loved Milwaukee, and none of us wanted to move, but it was hard for us to tell the good guys from the bad guys.”

In a cartoon entitled “But your honor, I don’t want a divorce,” artist Al Rainovic captured the feelings of many Milwaukee fans who were coming to terms with the Braves’ relocation south. (UWM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT RAINOVIC COLLECTION IMAGE 250)