Photograph posed for Hitler in the yard of King Hans Gades Jail: Knud (1), Jens (2), Mogens F. (3), Eigil (4), Helge (5), Uffe (6), Mogens T. (7), Børge (no number); man at right unknown

KNUD PEDERSEN: A very few hours later I was jolted awake by the voice of a guard. “Put on your clothes. You are going to court! Now.”

I rubbed my eyes and looked around. Jens had grabbed the only bed; I had fallen asleep on a floor mattress. Pale light filtered in through a barred window high in one of the four walls. At the other end of our small, oblong cell was a solid door with no handle and a peephole covered on the outside—so that the guards could check on us but we couldn’t see out. A table and a stool were bolted to the linoleum floor. That was it. Home.

We were transported to court by bus with Danish uniformed police guards, one guard for each of us. Outside the bus window the streets were filled with people bustling to work and school as usual, except, of course, that under German occupation they were no freer than we were.

The courtroom was a solemn square chamber with high windows and a polished linoleum floor. It took only a few minutes for the judge, barely looking up from his papers, to extend our confinement by four weeks and send us back to our cells.

* * *

As Knud and the others were being transported to and from court, Rector Kjeld Galster, the Cathedral School principal, stood before the students at morning assembly and informed them that six of their classmates had been arrested overnight and charged with sabotage against the German Army. He read their names out: Knud Pedersen. Jens Pedersen. Eigil Astrup-Frederiksen. Helge Milo. Mogens Fjellerup. Mogens Thomsen. Your classmates, he said, are now behind bars at King Hans Gades Jail.

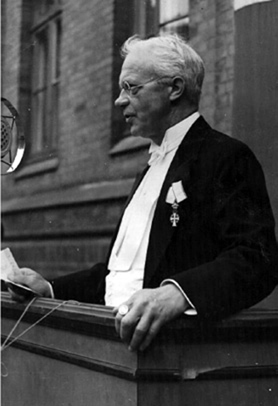

Cathedral School principal, Rector Kjeld Galster

Some students rose from their seats and ran out of the building. Teachers stood aside. Students massed outside the jail chanting and cheering for their classmates.

The boys, in court, did not hear them.

Other students remained at school, deeply shaken. One later wrote, “The announcement was completely shocking to us. These six guys who, as late as the day before yesterday had walked among us at school, learned their lessons with us, and played with us on the school grounds, had in their nonschool time made sabotage against the Germans … The rector urged us to go to our classes and resume our work. But it was hard … We developed a gruesome picture of the fate our companions would share. We sat and looked across the empty benches where our arrested comrades used to sit. One of our teachers sat for an hour with his head buried in his hands and did not say a word to us.”

Another Cathedral teacher found something constructive to do with the powerful feelings that seized him when he heard the news. It was Knud’s shop teacher. He knew that Knud hated shop class and had no interest in woodworking. For almost a semester now he had yelled at Knud, berating him as lazy, calling him inept in front of the other students. Regret overwhelmed him. Out of deep admiration for what the boy had been doing, he set to work on finishing Knud’s class project. And when he was finished, he delivered a finely crafted table to the monastery and left it as a gift for the Pedersen family.

* * *

Word of the sabotage cell and the boys’ arrest swept quickly through the city of Aalborg.

Gossip raged in shops, offices, schools, and factories.

Behind the scenes, German and Danish officials were already engaged in tense negotiations. These were the first sabotage arrests in Denmark during the war—all eyes would be on this case. The big question was: Who would conduct the trial, Denmark or Germany? If the boys were convicted, under which system of justice would they be punished? If German authorities issued the sentences, the boys could wind up in pitiless work camps at best. At worst, should Hitler decide to treat them as public examples of what happened to people who dared to resist, they could be executed. If the Churchill Club was tried in Danish court, the Danes’ German masters would surely insist on quick convictions and harsh sentences to show the world that the Third Reich meant business.

And there was something else at stake: the deal between Germany and Denmark. Many Danes were content with the occupation. Money was being made; their homes were still standing. For their part, German soldiers and officers were well fed, had the run of Denmark’s cities, and barely had to lift a finger to preserve the status quo. No troops were needed to police the Danes; the mere threat of German military might kept them in line. For many on both sides it was a sweet arrangement. But these boys had stirred things up, and how they were handled was important. On the one hand, the Germans did not want to arouse public anger by crushing these Danish youths, but on the other hand, they couldn’t appear to be weak either. It was a very delicate situation.

Three days after the boys were arrested, the Aalborg City Council delivered a contrite letter to German authorities apologizing for the Churchill Club’s behavior. Signed by the mayor, it said:

Aalborg City Council has unfortunately received word that a number of young people who are pupils at the Cathedral School … have undertaken varying and extremely serious harassment of the German Army … On behalf of the people of the city, the City Council expresses deep regret … concerning these actions. This has given rise to sorrow and dismay in many homes, which—the council has been assured—had no idea of the illegal actions which have taken place. The City Council furthermore expresses their hope that what has taken place will not lead to serious consequences for the continuation of the good relationship between the German Army and the Danish State and Council Authorities.

In the end, Germany allowed Denmark to conduct the trial, but with conditions. First, the Germans insisted that Rector Galster be removed as head of Cathedral School and banished from Aalborg. Second, the occupiers made it clear that during the trial a German observer would be in the courtroom at all times, watching carefully and reporting to Berlin. A judge and a prosecutor were summoned to Aalborg from the nation’s capital, Copenhagen, to conduct the trial of the Churchill Club.

KNUD PEDERSEN: In jail we were treated differently from other prisoners. For one thing we were different from other prisoners—a pack of teenage boys from a private school. The police were used to drunks and thieves. Beyond that, we were behind bars for actions that some of our jailers deeply admired. We were star prisoners, receiving the best treatment our jailers could give us. Kristine, the pastry shop from which we had stolen three pistols, sent coffee over to us. Even Holle’s, the café whose waitress had ratted us out, started sending over cream cakes for us. And, even though we were in deep trouble, we had the cheer and energy of teens everywhere. We made the best of our situation. And we were deeply, to the core, irreverent.

From time to time we were taken to see a doctor assigned to assess our mental health. It would have been convenient for Danish officials to report that tests indicated that insanity had driven us to sabotage. Our doctor looked deep into our eyes and asked such questions as “If I gave you ten thousand kroner, how would you spend it?” Alf told me he answered by saying, “Thank you, but that’s too much money. I’d feel better with five thousand.”

The doctor gave us written exams to test our general knowledge:

“Why do the seasons change between summer and winter?”

“When did Queen Elizabeth reign?”

“What is the capital of Portugal?”

“What is gratitude?”

Now that last question was interesting. One of us answered with “If I get ten years and stand up and say ‘Thank you,’ that will be gratitude.”

We were permitted an hour outside in the prison yard every day. We would be in our cells reading and writing, or building model airplanes, or trying to sleep, when keys would rattle in the door and a jailer would shout, “Recreation time!” We were led into one of two cement dungeons with walls about ten feet high and mesh netting over the top. Some of us played chess, others played ball games. Once when we heard German soldiers tromping outside the walls, bleating one of their stupid farm ballads, we quickly countered with “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” the marching song made famous by British soldiers during the First World War. The Germans complained to the prison authorities.

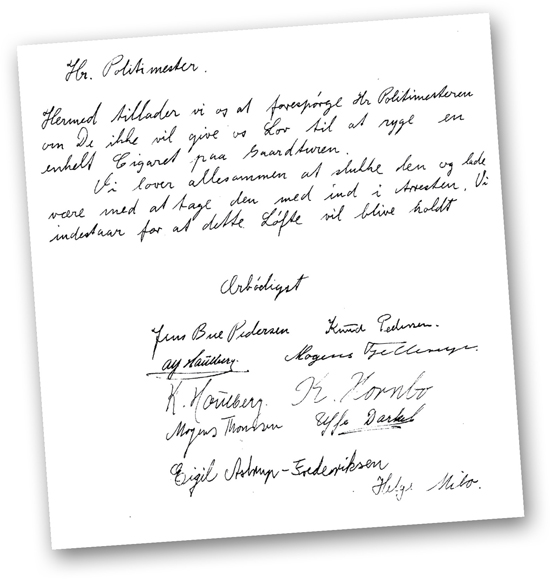

We wrote a letter to the police commissioner, seeking permission to smoke during outdoor time. “We ask you, dear commissioner, to let us smoke a single cigarette,” we wrote. “We promise to stub it out and promise not to take it into the cell. We guarantee you this promise will be kept.” We all signed it. And it worked!

Every day we made up plays and skits that mocked the authorities. We played trial scenes over and over in the jail yard, imitating the court officials we were coming to know. The plays always ended with the death penalty to all of us—we put a white hanky over our hearts when we died—and, no doubt about it, we were deeply worried about being executed. We spent a lot of time discussing how they would do it. Shoot us? If so, all at once in a row or one by one? Would it hurt? For how long? Someone had seen a movie where Nazi-like thugs had executed a bunch of prisoners. The goons used the same shirt, which had a hole in the heart, and put it on each new prisoner to be shot so they wouldn’t have to dirty a new shirt each time. At King Hans Gades Jail we had one cell containing an older prisoner, a guy who said he had murdered his wife when he found out she was a Nazi. This guy pretended he knew everything about everything. He said he had heard that the suffering from execution could last for a half hour.

Letter to the Aalborg police commissioner seeking permission to smoke a cigarette during outdoor time

Each of us handled confinement differently. I was all nervous energy. I made a clutter of everything, strewing drawings all over the cell, while Jens was tidy by nature. This had been okay when we lived in separate rooms in the monastery, but now we were thrown together twenty-three hours a day in a tiny cell. For a while he blocked me out as best he could, trying to concentrate on reading The Brothers Karamazov. But one day he scowled over the book and told me to shut up. Soon we were nose to nose, voices rising as we blamed each other for doing things that got us all arrested.

Jens: Why did you tell the police about the three guys from Brønderslev who gave us the grenades? You didn’t have to. We could have saved them!

Me: I had to explain the grenades because you led police straight to our stash in the cellar.

Jens: I didn’t show them the cellar. You told them about it.

Me: All I told them was that you were my brother. And why did it even come up? Because you had the brains to trip a German skater on an ice rink and get yourself on an anti-Nazi watch list. What an idiot you are!

Jens: Bloody Nazi!

Me: Bloody Communist!

Then we were swinging, two brothers who loved each other but who had been in a pressure cooker for more than half a year. All the Churchill Club meetings were at our home. All roads led to us. It just got to be too much, and it all came pouring out that afternoon.

Everyone in the prison started yelling, and guards rushed in to separate us. They put Jens in the cell next door, locked in with Alf. There were sore feelings as we went to bed that evening, but in the end this arrangement allowed us to combine our talents productively.

One day the guards summoned us to the prison yard for a photograph. We were surprised to see Børge again, the first time since the night of our arrest. He had been arrested like all of us, but was too young to be charged as an adult. He said he was spending his time in a youth correctional facility. We were each given a number to hold up in front of us and told to spread out side by side. We started to make fun of the whole thing as usual, but a guard brought us up short: “You’d better look as serious and sad as you can,” he said, “because these photos are going straight to Berlin. Hitler himself may see them. You would be very wise to wipe those smiles off your faces.” And we did. And suddenly Børge’s appearance made sense. As the youngest and most innocent-looking of us, he helped make the impression, one that Danish officials desperately sought to convey, that we were just innocent schoolkids who had been caught on a lark.

* * *

Knud and his fellow club members remained behind bars as spring turned to summer, and word of the Churchill Club’s arrest continued to spread throughout Denmark. Despite heavy German censorship, there was no keeping the Aalborg student saboteurs out of newspapers and radio broadcasts. Whatever their age, these Churchill Club boys were organized Danish resisters, the first flesh-and-blood evidence that Danes could stand up to the German occupation. Years later a Cathedral classmate wrote, “[Their arrest] came as a bombshell to us. Today it is difficult to imagine what an enormous impact the unveiling of the Churchill Club meant to the Danish population … The spiritual shock effect was tremendous and lasting.”

In the privacy of their homes, people talked about these boys from Aalborg. Some Danes were embarrassed that it took young students to stand up to the Nazis. Some feared that the boys had made things worse for everyone by arousing the giant. One Aalborg newspaper columnist lashed the boys for “foolish acts against foreign troops … They are not heroes, but fools and rascals who, through their irresponsible and unconscionable behavior, are guilty of crimes that put our city and our country in further danger … They should be whipped until they learn to realize this.”

In contrast, many were inspired. A leaflet circulated through Aalborg’s streets and shops urging citizens: “View the arrested young people and parents with sympathy! Show that you do not hate them for their actions, but rather consider them to be good Danish patriots who deserve the respect of all Danes. Create a supportive atmosphere, so the Germans will think twice about dragging them abroad or shooting them.”

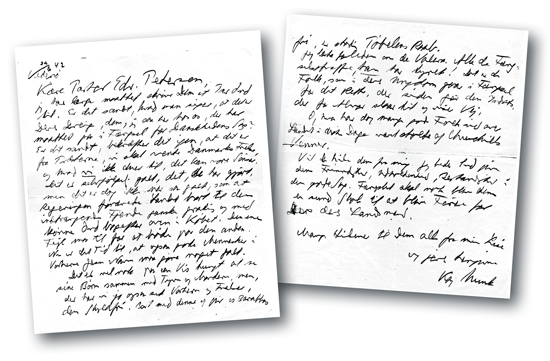

Kaj Munk, Denmark’s most famous poet and playwright, wrote a sympathetic letter to the Pedersens’ parents. The contents were published in an underground flyer that moved secretly throughout Denmark. Munk wrote: “Of course what [the boys] have done is wrong; but it is not nearly so wrong as when the government gave the country away to the invading enemy … Now it is time that good people in our Lord Jesus’s name must do something wrong … I pray to God to give them cheerfulness, endurance, and constancy in the good cause.”

Letter from Kaj Munk to Edvard Pedersen

Kaj Munk

Kaj Harald Leininger Munk, commonly called Kaj Munk (1898–1944), was a Danish playwright, poet, Lutheran priest, and activist.

Munk’s plays were mostly written in the 1920s and performed during the 1930s. He wrote about deep subjects such as religion, Marxism, and Darwin’s view of evolution.

Munk at first expressed admiration for Hitler’s success in getting Germans back to work during the Great Depression, but his attitude soured as he observed Hitler’s persecution of German Jews.

His plays Han Sidder ved Smeltediglen (He Sits by the Melting Pot) and Niels Ebbesen were direct, powerful attacks on Nazism that aroused Hitler’s ire. The author was arrested and subsequently assassinated by the Gestapo on January 4, 1944.

Kaj Munk

Kaj Munk is a Danish national hero. He is commemorated each year as a martyr in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church on August 14.

* * *

The Churchill Club boys gave testimony individually and in small groups for a period of about ten days throughout the early summer of 1942. The presiding judge was Arthur Andersen, an experienced jurist who had been specially called to Aalborg from the Copenhagen court. He was accompanied by his secretary, a man named Silkowitz, there to produce a written record of the trial. The Churchill Clubbers remember that throughout the trial the secretary constantly interrupted the judge, asking “Is this to be written down?” or “Am I to omit this part?”

The German consul sat stiffly and in full uniform at a small writing table, carefully listening to testimony and jotting down notes. When his hand moved, eyes followed. There were no parents, journalists, or friends in the courtroom. The atmosphere was businesslike.

KNUD PEDERSEN: We had two defenders. One was Lunøes from Copenhagen. We didn’t like him because he portrayed us as unruly children. Our local defender—from Aalborg—was a fat, jovial character named Knud Grunwald. He was always shouting and threatening us and warning us not to say anything against the Germans. Grunwald repeatedly came to see us in the jail, trying to prepare us for the trial. He would pace back and forth shouting, “Now you regret what you did, don’t you! Answer me! Do you regret it?” He would answer himself before we had a chance to make a sound. “You sure as hell do! You better remember that the German consul in Aalborg will report straight to Berlin. Hitler will hear about this! Remember that when you are in court!”

Judge Andersen took a kinder, softer approach. One day he said to me, “Today, Knud, you’re going to tell about your activities in Odense. You can tell me everything because you were only fourteen years old at the time and cannot be punished for juvenile activities.” Of course I didn’t mention the names of the RAF Club members, which was what he wanted.

The key to it all was the weapons; that’s what they cared about. Why had we stolen them? What were we going to do with them? Our defender, and surely our government, wanted us to testify that we collected them to keep as toys or souvenirs, to show off for our friends, or just to see if we could get away with it. We were just kids looking for adventure—that’s what they wanted us to say.

During one of the sessions, Judge Andersen summoned four of us to stand before him and asked us one by one why we stole the weapons. When my turn came I told the court that the weapons were not playthings to us. We planned to use them to support the British when they came to liberate us. Grunwald leaped up and asked the judge for a recess until the next day. It was granted, and court was adjourned.

That night Grunwald rushed into the jail and filled the building with his angriest speech yet. “You had almost made it!” he sputtered. “The judge could have ruled that you had no intention to use the guns! And then this idiot here—he pointed at me—testifies that your brilliant idea was to shoot the Germans with their own guns! You fool! Now I’m going to try to get you one more chance, and you’d better not mess up!”

The next day, Grunwald asked the judge to repeat the questions from the day before. I saw the German representative stop his hand and look up when it came my time to answer.

And of course I repeated exactly what I had said the day before.