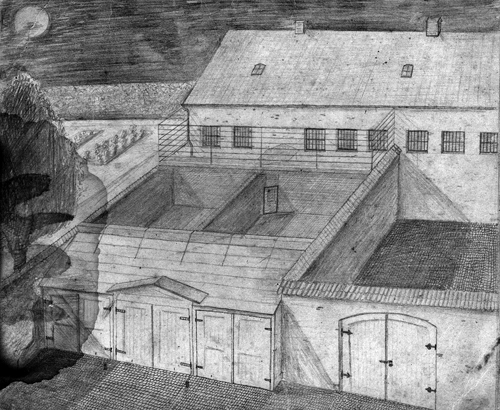

Alf Houlberg’s drawing of King Hans Gades Jail, showing the two exercise yards that were covered with netting

KNUD PEDERSEN: Escape was on our minds from the very start. We were not helping our country resist the German occupation by remaining in confinement. Naturally, we tested every bar and brick and lock in that old jail. Even though we were supposed to surrender our clothing to the guards each night so we wouldn’t escape, we started hoarding and hiding shirts and trousers, so certain were we that somehow we’d find a way out of there.

The top of the outdoor jail yard looked like the best bet. Though the yard was enclosed by thick, high stone walls, the top was capped only by a thin wire net. If you could reach it, you could cut it. We were left unguarded during our two daily thirty-minute outdoor sessions, so we had time to work. One morning I—the tallest—cupped my hands and boosted Uffe up onto my shoulders. He scrambled to a standing position and then, steadying himself against the

wall, fumbled in his pocket for the kitchen knife we had smuggled into the yard. In a minute he had ripped a nice opening.

The idea was that one of us would pull himself out through the hole, inch along the top of the wall, and jump down into the prison commissioner’s garden and scoot on out. He would make contacts on the outside and find us a place to hide. Unfortunately, the very next day one of the jailers walking across the yard glanced up and noticed the hole in the netting.

That was the end of unguarded yard time. On to Plan B.

Our ultimate goal was Sweden. The Nazis had for some reason allowed Sweden to be officially neutral. That meant that if you could get there, you were safe, at least until the Nazis changed their minds. In some parts of Denmark, near Copenhagen, you could easily see Sweden from our shore—it was a very short boat ride away. It would, however, be much harder to get there from Aalborg, where we would first have to clear the heavily guarded fjord and then proceed another six or eight hours to Swedish waters. In either case the challenge would be to find a captain who would risk going over. That would take underground contacts and probably money, of which we had neither at the moment.

Neutral Sweden

At night, while Danes and Norwegians covered their windows with black sheets and lit their streets with blue lights that couldn’t be seen from the air, nearby Sweden appeared to be a carnival of light. Swedes took an officially neutral position in the war—meaning they didn’t take sides. Sweden played on both teams. On the one hand, the whole German military effort depended on weapons made from millions of tons of iron ore, which Sweden exported to Germany through Norwegian harbors and the Gulf of Bothnia.

On the other hand, Sweden defied Germany by taking in war refugees, most notably the great majority of Denmark’s Jews in October 1943, hours before a planned German roundup. It was logical that Sweden was the planned escape destination for the Churchill Club.

Our plan was to hide out in the legendary Thingbaek limestone cavern about twenty miles south of Aalborg. It had been purchased by a businessman who mined chalk out of a portion of it, but there were still plenty of corners to tuck ourselves away in for a few days. Our only neighbors would be the countless bats that hung from the ceilings by day and poured from the cave in chattering clouds at dusk. Like the bats, at least we would be free.

To arrange help on the outside, my sister, Gertrud, smuggled our messages to Børge’s older brother, Preben. He was a classmate of Jens’s at school, a well-dressed, big-talking kind of guy who repeatedly tried to convince Jens to make us stop our sabotage activities. Preben had been present at the first Churchill Club meeting, but he had never returned. He seemed horrified that his little brother had fallen in with Jens and me—as if we had corrupted poor innocent Børge. Still, he had helped us in the past and we thought we could trust him.

One visitation day we gave Gertrud a letter for Preben describing our escape plan. We asked Preben to deliver an enclosed letter Jens had written to the mine owner, seeking permission for us to stay in his mine until we could work something else out. Our final words to Preben were “Burn this letter.” Preben was supposed to relay the owner’s reply back to us through Gertrud. Instead he took our request straight to his parents. They were outraged. Gertrud soon brought us a letter from Preben that said, basically, “You guys are out of your minds. I’ll have nothing to do with this idiocy. If you persist in this inept escape fantasy, I myself will turn you over to the police to save your lives. I’ll think of something when the time is right. Sit tight.”

But we didn’t just “sit tight”—how could we?

* * *

Early on the morning of July 17, 1942, Knud and the other boys were jolted awake by the jangling of keys, and the gruff command “Get dressed!”

KNUD PEDERSEN: They had placed our very best clothing on the stool outside the cell door. That could mean only one thing: the judge’s verdict was ready. After nine weeks in the local jail, we would now learn of our future. Were we to be executed? Handed over to the Germans? Freed? Or had the Danes and Germans made some sort of deal for us to be punished in Denmark? Now we would find out.

We were ushered into vans and driven to court. Through our windows we observed trees now in full leaf, shading women in summer dresses and men in shirtsleeves. We inhaled the beautiful aroma of hot pastries sold from corner kiosks. German wagons filled with soldiers rattled toward the waterfront.

Our guards led us into the courtroom. I had no idea what our fate would be. I certainly had no regrets for what I had done—except that I had been captured. I doubt that my mates did either. We were patriots. Our enemies were the Germans who had stolen our nation and the Danes who had stood by and let them take it. Our heroes were still the Norwegians who continued to fight bravely and the outnumbered British pilots who heroically defended their country from the Nazis’ relentless aerial attack. We were at war, and I was simply a soldier who had been captured. I was prepared for any outcome.

The courtroom already held the morning heat. The German monitor was at his table, face expressionless, uniform pressed, notebook open. Judge Andersen rose with a yellow paper in his hand and called us to approach his desk. Our prosecutor and our defense lawyer climbed to their feet as well. The judge read out our names and the charges against us: Wanton destruction of property. Arson. Theft of weapons from the German Army. He pronounced us all guilty as charged. We were to be punished by imprisonment at Nyborg State Prison, an adult penitentiary, southeast of Odense, nearly two hundred miles away. He did not say exactly when we would be transferred.

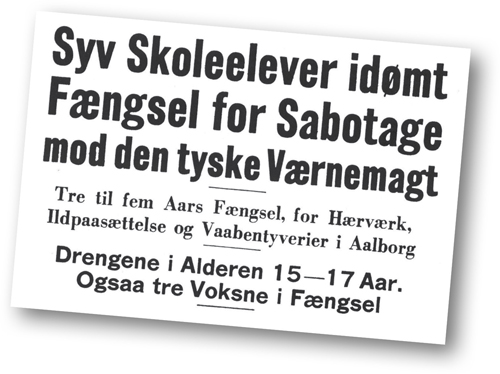

We each got different sentences, depending on our age and the number of counts against us. The scorecard read as follows:

Knud Pedersen: Three years, for twenty-three counts

Jens Pedersen: Three years, for eight counts (but he was eighteen months older than I, so he and I got the same)

Uffe Darket: Two years and six months, for six counts

Eigil Astrup-Frederiksen: Two years, for eight counts

Mogens Fjellerup: Two years, for eight counts

Helge Milo: One year and six months, for nine counts

Mogens Thomsen: One year and six months, for four counts

Our three older colleagues from Brønderslev received longer sentences, because they were adults in their twenties. The sentences were:

Knud Hornbo: Five years, for one count (passing the grenades to us)

Kaj Houlberg: Five years, for one count (same)

Alf Houlberg: Four years and six months, for four counts

We were also sentenced to pay court costs—such as the expense of employing our “brilliant” defender, Grunwald. In addition Jens, Uffe, Alf, and I were ordered to repay the German Army for all their property we’d destroyed. The tab was exactly 1,860 million kroner, or 12,538 Reichsmarks (roughly $400,000 today). No problem, we thought. We’ll have a check to you in the morning post.

Headlines about the Churchill Club’s sentencing from an Aalborg newspaper: “Seven Schoolchildren Sentenced to Prison for Sabotage of the German Wehrmacht / Three to Five Years Imprisonment for Vandalism, Arson, and Weapons Theft in Aalborg / Boys 15–17 Years Old. Also Three Adults Imprisoned”

According to Danish law, we would be eligible for parole after two-thirds of our sentences had been served—two years and a month in my case and Jens’s. The instant that Judge Andersen banged his gavel and dismissed the case, Grunwald came up to us, waving his arms, and stuck his florid face close to ours, shouting, “Now do you regret it? Now do you regret it? You sure as hell do!”

As we were leaving the courtroom, Judge Andersen called my name and beckoned me back to his desk. There were tears on his eyelashes, and his voice caught as he spoke. “I learned of your attempt to escape from the jail,” he said. “I have done everything I could for you. Please, promise me one thing … for your own good, Knud. Don’t try to escape again.”

* * *

Family visitation day came just after the prisoners were sentenced. There was a big turnout—not surprising since it might be the last they would see each other for a long time. The authorities let the boys mingle as a group in the jail’s front room. Kristine pastry shop sent over cream pies. Relatives brought food, smokes, and reading material. Given the circumstances, it was about as festive as a jail gets.

KNUD PEDERSEN: At one point, as prisoners and family members embraced, Alf’s younger brother Tage slipped Alf a magazine. Inside was a hacksaw blade, about fourteen inches long. By the time a guard asked to see the magazine, Alf had already concealed the sharp, supple blade, dropping it into a hole in his jacket pocket that he had cut the week before when Tage told him to expect the tool. Later, waving goodbye, he walked it into his cell. We had another chance!

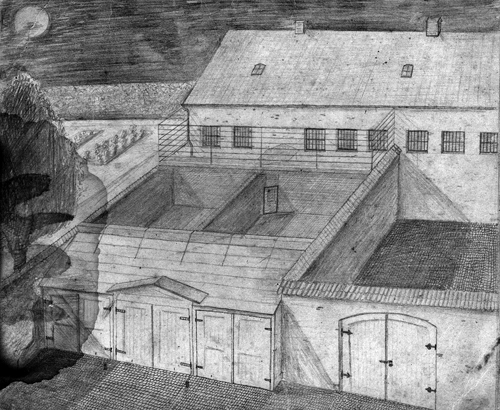

The roof of King Hans Gades Jail, showing the barred window (in foreground) for which Jens and Alf made a dummy bar

Jens and Alf—now cellmates—set to work that very afternoon. Forcing a slender blade back and forth against a square metal bar proved to be slow and noisy work. They could only work by daylight, for there was a strict bedtime curfew and mandatory silence at night. Alone in the cell next to them, I tried to provide as much noise as I could. I became a drummer, improvising long sessions with spoons on a metal cake box. Together we Churchill Clubbers howled every song we knew through the window bars in our cells. There were all sorts of songs about Hitler and his henchmen. One went:

First we grab old Göring

By his big fat calves.

Then we knock down Goebbels—

We don’t do things by halves.

We’ll dangle Hitler from a rope

And right beside him Ribbentrop:

Look how stupid, all in line,

One, two, three, four Nazi swine.

With transfer to state prison looming at some unknown date just around the corner, Jens and Alf worked like demons, sawing for our freedom. We had no way of knowing when we’d be moved—days? weeks? months? We just knew we wanted to get out of there before the bus came to take us away.

The task wasn’t simply to cut out a section of the central bar in the cell window; we also wanted to replace the bar so that no one could notice it was missing during daylight hours. Jens ingeniously constructed the perfect mechanism—a dummy bar with a wooden pin on one end that fit into a slot in the bar. If a guard happened to pull on the bar during our weekly inspection, it would remain firm. The guard would have to push—which was unlikely—for it to move. It was a brilliant device: we could keep the bar on the window during daylight hours, and Jens and Alf could pass in and out of the jail at night. In this way we could continue with sabotage work at night and work out an escape for the entire group—without detection.

By early September we had opened up a section of the central bar big enough for a slender boy to pass through. But the color of the wooden pin was too light. It didn’t match the rest of the bar. So during yard time we took a stick and smashed a window. The next day when a guard replaced the broken pane, we scraped away some of the wet caulking used to secure the pane in place, applied it to our bar, and painted it over with black ink we had in our cell. It was perfect!

And then, just after work on the bar was completed and just before we had a chance to try it out, the keys jangled again and my cell door swung open. The guard ordered me to rise and get dressed. I looked around. It was still pitch dark. What was this?

* * *

By five o’clock on that September morning, Knud and the other boys were on a bus, each of them handcuffed to a guard, motoring toward Nyborg State Prison. The authorities had spirited them away from Aalborg in the dead of night so that outraged citizens would not have time to organize a protest on their behalf. On the bus were only the six Cathedral School students and Uffe—the Houlberg brothers and Knud Hornbo had been left behind. The boys rumbled through first morning light toward a bleak, faraway address with their friends and families receding behind them. It was about noon when the bus swung off the highway and they got their first glimpse of their new home.

As Churchill Club members, they had spent nearly a year striking rapidly, spinning out of harm’s way, and mocking the authorities from a safe distance. One look at Nyborg State Prison told the boys that they had finally run out of cards to play.