Liberation Day, May 5, 1945

Our Evening with Mr. Churchill

After liberation came the task of transitioning Denmark from an occupied nation to a free country. Some German soldiers refused to surrender. Danish Nazis, despised by their countrymen and with nowhere to go, had no choice but to fight to the bitter end. In the weeks after liberation, thousands of German soldiers just hung around Denmark, sometimes still running things, reluctant to return to a Germany that remained at war in many parts of the globe and whose cities, pounded by Allied bombers, had been reduced to smoldering ruins.

In the end, most Germans marched out of Denmark, laying down their weapons at the border. In the weeks following liberation, 15,000 accused collaborators were arrested and tried in Danish courts. Of these, 13,521 were found guilty and 46 were executed.

The organized resistance helped manage the swing back to a Danish-run government. As a company group leader, Knud Pedersen was ordered to take his men to a building at Aalborg’s civilian airport to oversee the transition from German to Danish management. He expected the change to be well under way, but when he and his men arrived, they were shocked to find that the airport was still run by Germans.

Danish citizens were still flashing identity cards to German masters just as they had throughout occupation. Knud and his men moved rapidly to take over.

KNUD PEDERSEN: I gave the order to confiscate all identification cards and give Germans employed there two hours to gather their belongings and depart. The German commander came out boiling mad, and I told him to leave at once. Within minutes a crowd of motor traffic was closing in on us from all over the airport—English jeeps with British Tommy soldiers and Danish resistance cars spilling over with officers.

My chief canceled my orders at the airport base and ordered that everyone’s ID cards be given back. I was ordered into a car and driven to our headquarters, where I was lectured.

I had exceeded my authority, my chief said. I had strayed outside of command. “You will obey orders from this moment on,” he said.

German troops departing Denmark

A possible Nazi collaborator under arrest by Danish police

I refused.

How could I obey? The scene at the airport was firsthand evidence that elements of the resistance had been corrupted. Now reports were coming in that Danish authorities had already freed German sympathizers from some prisons. Was that what we had fought for?

I found other group leaders who were just as frustrated as I was. Together we wrote out a list of five demands to govern the transition:

1. All Germans should be put behind bars.

2. Danes should stop trading with Germans.

3. Collaborators should be arrested at once.

4. Food for German soldiers should be rationed.

5. The resistance should be cleansed of corruption.

I took the five points to a printer, who promptly left the room and called the police. My company chief found me, relieved me of my command, and confiscated my weapons and ammunition. Now I was on the street again, with no command and no future in the resistance. I glumly returned to the monastery and mulled my options. None looked good.

I was still in a dark cloud a few afternoons later when, to my total surprise, a car from K Company came screeching up to the monastery. The same men who had dismissed me days before now hailed me warmly and returned my machine gun, ammunition, and signs of grade. What could have happened?

It turned out that Major General Richard Dewing, the British commander of all military forces in Denmark, had come to my rescue—not that he meant to. Now that liberation had come, he wanted to meet the legendary Churchill Club, Denmark’s first resisters. He would soon be visiting Aalborg. He ordered his staff

to round up as many Clubbers as they could find and have them at the Hotel Phoenix at a certain time.

We were all astonished by the meeting. Uffe Darket told us that a British Royal Air Force plane had shown up at his post in Germany, with a pilot whose orders were to take him to Aalborg, Denmark. There was no explanation, just “Let’s go.” Helge, Uffe, the Professor, Alf, all of us—everyone had a similar story.

General Dewing meeting with the Churchill Club (the general is at the head of the table, Knud is to his immediate right)

On the day of the meeting we were seated at a long table in the hotel dining room with General Dewing at the head. He greeted us individually, by name. He said he wanted to know our whole story, from Odense to Aalborg to Nyborg State Prison and beyond. So we detailed our lives first as angry schoolboys, then as increasingly bold saboteurs, and then as prison inmates. We gave him the late-night raid on the Fuchs Construction Company’s headquarters at the airport, and remembered how good it felt to use the framed photo of Hitler as a trampoline. We told stories of stolen weapons, ruined autos, and scorched railway cars. He laughed out loud when we came to the dummy bar on the cell window at King Hans Gades Jail. He asked question after question. Finally, he pushed his seat back and stood. “This is a good story,” he said, saluting us. “I’ll tell it to Mr. Churchill.”

* * *

Winston Churchill did indeed hear the story, but probably not from General Dewing. Five years later, in the autumn of 1950, Denmark was no longer preoccupied with the war. For the first two or three years after liberation, the air had been thick with accusations and demands for justice to the traitorous collaborators, but now there was a sense in the population of getting on with things, that the horrible hour was at last behind them, that the sun was shining again. The Churchill Club had scattered, and there had never been a reunion. Most of its members were launching careers and starting families.

KNUD PEDERSEN: I had moved to Copenhagen. At that time I was taking a few classes at law school, but my real love, as always, was art. I spent all the time I could painting and talking late into the night, debating and learning about new trends in modern art. Like all young students in Copenhagen at that time, and especially art students, I barely had enough money to buy a cup of coffee. To get by, I got up each morning at five to deliver newspapers, and I also worked in a brewery, sorting empty bottles. It was about as challenging as the work I had done at Nyborg State Prison.

One night I got out of a class and was hurrying across a city square to meet some friends when I glanced up at the electronic headline wrapped around the top of a newspaper building. It read, “Churchill Club to Meet Winston Churchill.”

I stopped. Pedestrians rushed past me as if I were a stone in a stream. I stumbled to a telephone box in the middle of the square, but I couldn’t scrape up the right coins to call home. Just then, my glance went to a broad white banner stretched across the front of a hotel next to the newspaper building: CHURCHILL CLUB MEETING HEADQUARTERS. I gave my name to the lady at the reservation desk and asked for a telephone. She said they had been trying to find me all day.

Old clubmates trickled in through the night and the next morning. Unfortunately, Jens was working as an engineer in India and could not attend. Some were university students and still knew each other, but I had lost touch with nearly everyone. Several were fathers now—I hoped that was in my future.

* * *

Sir Winston Churchill’s main business in Copenhagen was to accept an award for outstanding contributions to European culture. The award ceremony would be held the following night at Copenhagen’s three-thousand-seat KB Hall. The Churchill Club members were still puzzled as to exactly how all this had come about, but they went along with the attention and the opportunity to meet Churchill. The event’s sponsor was a newspaper whose reporters and photographers had endless ideas for publicizing the event, including giving them all big Winston Churchill cigars to smoke while camera shutters snapped.

The following day, while Winston Churchill and his family lunched with the Danish king at the castle, the Churchill Club enjoyed a luncheon in their honor at the hotel. The master of ceremonies was Ebbe Munck, a resistance hero who had been the contact between the secret British sabotage organization SOE and the Danish military intelligence. When he spoke, the Churchill Club members finally found out how they had come to be honored.

KNUD PEDERSEN: Ebbe Munck said he had sat next to Churchill on the flight crossing the North Sea from London to Copenhagen just a couple of days before. That gave him the chance to tell Churchill how and why the club was formed, about the work we did, and why we named ourselves after him. Munck told us that Churchill was moved, and felt strongly that our contribution had to be acknowledged. The moment was now—who knew when he would be back in Denmark? Round up as many of them as possible, Mr. Churchill had told Ebbe Munck. And that’s how we came to be gathered—hastily—here at this hotel in Copenhagen. Although Churchill could not focus on the Churchill Club in his acceptance speech, he wished to greet us in an honor parade just before his remarks, acknowledging us much as a general passes by troops on a tour of inspection.

When the big moment came, I confess that I was absent. I missed the parade. I got separated from the group, and by mistake I went in the wrong door to the hall—in the VIP entrance where Churchill and his wife and the officials entered. I was only two meters from Churchill when we walked in. Our eyes met for a moment. It felt like I was looking into the devilish eyes of a confidant, eyes that almost winkingly said, “Don’t believe all you hear about me.”

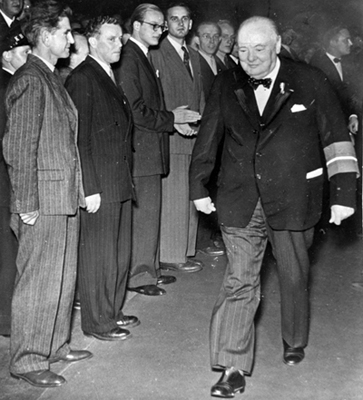

Winston Churchill reviewing the Churchill Club

An attendant at his side bowed slightly to me and said, “Your card, sir.” I withdrew my invitation from my pocket and showed him. I hadn’t read it and didn’t know what it said. But whatever it was, it was magic. He returned the card and led me to a special VIP box. To my left was Prince Knud, representing the royal family. To my right was Admiral Erhard J. C. Quistgaard, chief of all Danish military forces on land and sea and in the air.

When the lights went down for Churchill’s acceptance speech I slipped the card from my pocket and drew it close to see what it said that could have possibly landed me in such a high-rent district.

It was a simple business card. Below my name was my title. It was the same title that had landed me in two Danish prisons. It had inspired robotic guards to try to reduce me to a number. My title had been cursed and lauded in thousands of living rooms and kitchens and workplaces during Denmark’s bleakest hours. It was a title I had taken on as a boy and would wear with pride for the rest of my life. The card read:

Knud Pedersen

Member of the Churchill Club