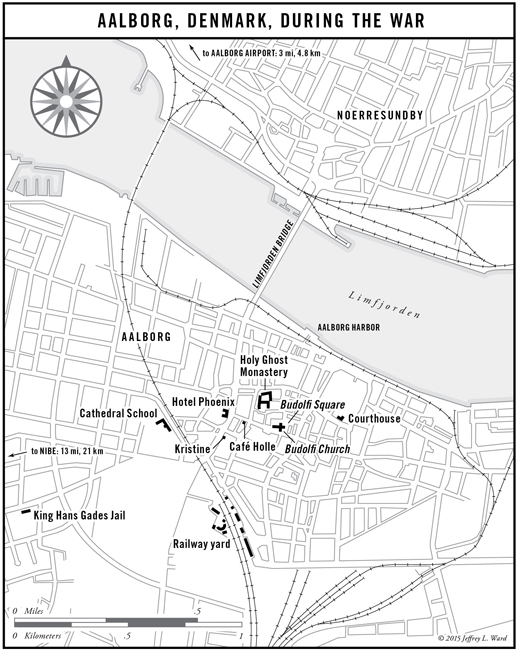

In the spring of 1941, Edvard Pedersen accepted an assignment to a new Protestant church and moved the family 150 miles north to Aalborg, a city in the northern part of Denmark called Jutland. Knud and Jens, now fifteen and sixteen, said reluctant goodbyes to aunts, uncles, and cousins; to languorous Sunday afternoons of card games and family plays; and, most important now, to the RAF Club. The Pedersen brothers pledged to build an even stronger quick-strike sabotage unit in Aalborg. The RAF boys laughed in their faces. “You’ll never keep up with us,” they vowed.

Aalborg, Denmark’s fourth-largest city, was teeming with German soldiers. The big attraction for the Third Reich’s war planners was Aalborg’s strategically located airport. Within minutes on April 9, 1940, the German forces—some parachuting onto the airfield—had secured the airport and seized all the bridges spanning waterways in Aalborg. They immediately set to work building hangars and expanding runways.

Wagons filled with troops, many soon bound for action in Norway, raised the dust of Aalborg’s streets. German officers took over the best homes and hotels in Aalborg. Armed Wehrmacht soldiers joined the Danish population in restaurants, shops, and taverns. Before long, German soldiers stationed in combat zones enviously called Demark “the Whipped Cream Front.” The nickname suggested that German soldiers had it easy in Denmark, especially in contrast to troops on other fronts, where fighting raged.

Why the Aalborg Airport Was So Important

The Aalborg airport, situated in northern Denmark, was essential to the Germans as a refueling station to reach Norway, which they had to control in order to secure ice-free harbors in the North Atlantic. By controlling Norway, the Germans also opened up a route to transport iron ore for making weapons from mines in Sweden, going through the Norwegian port of Narvik. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, head of the German navy, said it would be “utterly impossible to make war should the navy not be able to secure the supplies of iron-ore from Sweden.” The Aalborg airport was therefore one of the most important single assets in all of Denmark. German forces cleverly camouflaged the airfield from attack by British warplanes by carving farm animals out of plywood and scattering the decoys about the grounds. From above, the cows and sheep lying near a green-painted runway suggested a peaceful Danish farm.

Troops awaiting transport at Aalborg

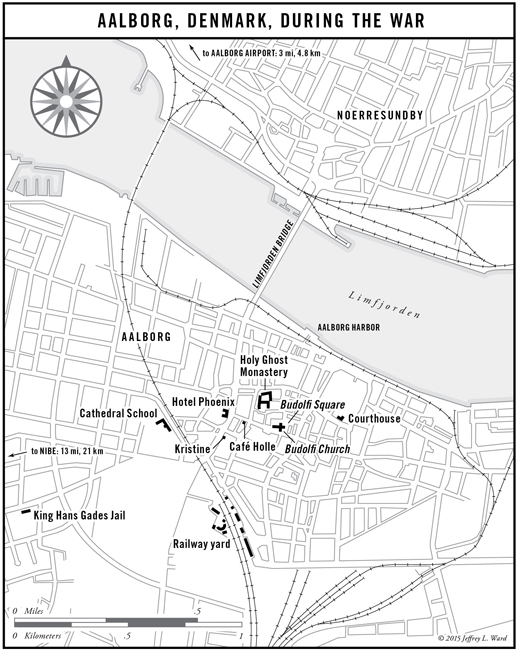

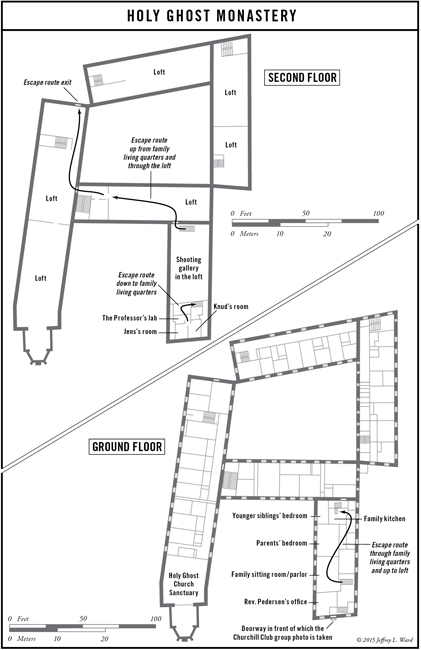

The Pedersen family moved into a drafty, vine-covered medieval structure with a towering loft. Built in 1506, Holy Ghost Monastery, as it was known, was actually a collection of buildings linked by arched passageways. Throughout the centuries the monastery had functioned as a Latin school, a hospital, a church, and the town library. Now it would host Edvard Pedersen’s Danish Folkschurch and provide living quarters for the Pedersen family. There was not enough money for electric heating, so each morning Margrethe Pedersen rose before dawn to light the monastery’s seven coal furnaces. As she padded down the cold tile hallways carrying her candles, faces of angels, frescoes painted centuries before, peered down from vaulted ceilings above. Hands from the sixteenth century had scratched their initials into the monastery’s brick walls.

Holy Ghost Monastery, Aalborg (front)

The “priest yard” of the monastery

Knud and Jens moved their belongings into adjacent rooms on the second floor. Drawing back his curtain, Knud looked out on a row of freshly polished German roadsters lined up on Budolfi Square outside the Aalborg post office. The vehicles were protected only by a single uniformed guard. If ever there was a perfect target, thought Knud, there it was.

They enrolled at Cathedral School, a college prep school that educated the sons and daughters of the city’s leaders. Hundreds of students rode their bikes to school each morning. The young cyclists were sometimes led by an absentminded math teacher who became famous for signaling left turns and then turning right, causing massive pileups.

Though Knud and Jens were eager to resume sabotage activities in Aalborg, they had to move carefully at first. There were pro-German students and faculty members at Cathedral School. It took time to get to know people. Which students could they trust? How to tell?

KNUD PEDERSEN: You couldn’t tell who you could count on to join a sabotage unit. No one but Jens and I had any experience. We knew that someone who talks big in a room can panic in the field. My first two friends at Cathedral were Helge Milo and Eigil Astrup-Frederiksen, both in my grade. We had classes together and then started hanging out after school, sometimes at the monastery. Eigil was a sharp character, always well dressed, talking loud and laughing louder, good with the girls. His dad owned a flower shop in the middle of town. Helge came from a well-to-do family in the neighboring city of Noerresundby. His father managed a chemical factory.

After a while I felt I could trust them enough to tell them about the RAF Club and to confide that Jens and I were interested in starting a similar sabotage unit in Aalborg. They wanted in. So one afternoon, as tryout, we three got on our bikes and rode off to cut some phone wires to German barracks. The barracks were in a forest, and naturally there were German soldiers all around.

Both Eigil and Helge panicked once we got close. Please turn around, they begged me. Let’s leave the wires for another day. So we did. I could understand—sabotage takes some getting used to. On the way out we pedaled past four German soldiers flirting with a Danish woman, and Eigil and Helge shouted out an insult as they sped by—they called her a “field mattress,” a slur for a woman who sleeps around with soldiers. Problem was, my classmates were in front of me and had already passed the Germans, but I hadn’t reached them yet. As I whizzed by they took off after us and soon had us surrounded, pinned down, bayonets drawn. They could easily have run us through on the spot. Somehow we talked our way out of it, and they let us go.

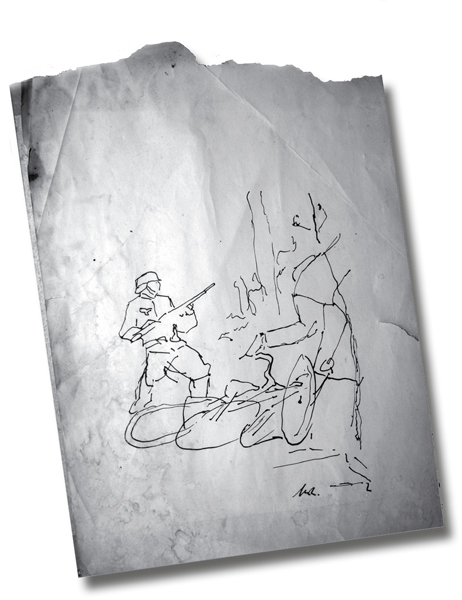

Knud’s 1941 drawing of a German soldier chasing Cathedral School students in the forest

* * *

German soldiers were everywhere in Aalborg, in the city, in the forest, at the waterfront, thick as flies. Some attended Knud’s father’s church on Sundays—he struggled with the idea of giving Nazis communion. At Cathedral School the gym was converted to barracks for about fifty German soldiers. When the girls from the school exercised in the yard the soldiers hung out the windows whistling and jeering at them.

Cathedral School exercise yard, 1943

KNUD PEDERSEN: One day a German officer walked across our schoolyard during our outdoor time. I went over to confront him and informed him he had no business there. We started shouting at each other as boys and soldiers gathered around. Then our rector came flying down the stairs to push me away, shouting, “You idiot! What are you doing? Get back in your classroom!” Nobody blamed him—as head of the school he had to do it or there would have been much worse trouble.

Just before Christmas 1941, a single conversation changed everything. We were in Jens’s room at the monastery. It was Jens, me, and four of my fourth-form Middle A classmates: Eigil, Helge, Mogens Thomsen—son of Aalborg’s city manager—and Mogens Fjellerup, a pale, pointy-faced classmate who rarely spoke but who was known as the outstanding physics student in our class. Two of Jens’s classmates were there, too: a boy named Sigurd—ranked number one academically in their class—and Preben Ollendorff, a bit of a loudmouth whose dad owned a tobacco factory.

We had just gone out shopping for Christmas presents for our teachers. We were in a great holiday mood, all of us tamping our pipes, laughing about girls, having fun. But as always the conversation snapped back to the German occupation of our country. You couldn’t go five minutes back then without returning to the topic on everyone’s mind.

The talk turned dead serious. We leaned forward and our voices lowered. We angrily discussed the newspaper articles about the execution of Norwegian citizens and slaughter of Norwegian soldiers who resisted the Nazis. Norwegians were our brothers, we reminded each other, our good neighbors who had the courage to stand up. By contrast, our leaders traded with Germany and sought to placate the Nazis.

Here was the discussion I had longed for! I was thrilled to be with Cathedral students who felt as my brother and I did. These were guys who stayed up like us for the nightly radio broadcasts from England. The more we talked, the angrier we became. It was absurd: if you accidentally bumped into a German on the street, you were expected to strip the hat from your head, lower your eyes, and apologize profusely for disturbing a soldier of the master race. All of us had listened to them braying their idiotic folk songs in the streets.

All this was outrageous, but would anyone do anything about it? Average Danes hated their occupation and occupiers, but ask them to resist and they would say, “No, it cannot be done … We will have to wait … We are not strong enough yet … It would be useless bloodshed!”

The air was thick with our tobacco smoke by the time we laid the proposition on the table. It was the same vow Jens and I and the others in the RAF Club had made back in Odense: We will act. We will behave as Norwegians. We will clean the mud off the Danish flag. Jens and I opened up and told our classmates of our sabotage activities with the RAF Club in Odense. We left with a bounty on our heads, we told them.

The discussion grew heated. The older boys, Sigurd and Preben, wanted nothing of it. “You’re crazy,” they said. “The Germans will wipe you out in a day! There’ll be nothing left of you!” But we younger boys were determined to give ourselves a country we could be proud of.

Together on that snowy afternoon we Middle A classmates, along with Jens, resolved to form a club to fight the Germans as fiercely as the Norwegians were fighting. We would take the resistance to Aalborg. We would call ourselves the Churchill Club, after the great British leader Winston Churchill. Jens volunteered to research the organization of a resistance cell and give us his recommendations, same time, same place tomorrow. Preben and Sigurd vowed not to leak word of our meeting to anyone. Already transformed from the cheerful holiday shoppers we had been an hour before, the Churchill Club stood adjourned.

* * *

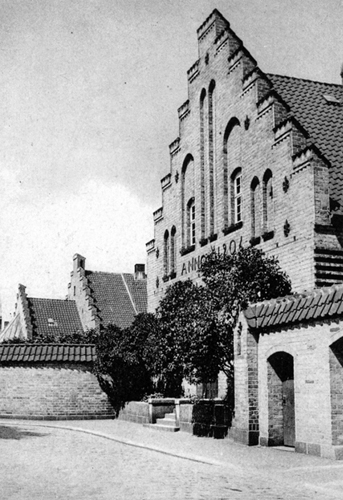

The next day after school, Knud and the other boys stomped the snow off their boots and tromped into Jens’s room in the former priest’s wing of the monastery for the first Churchill Club meeting. They draped themselves over a padded sofa and pulled the heavy wooden door shut. Knud took his position on a chair in front of the door to listen for approaching footsteps. And sure enough, they came, followed by a heavy pounding at the door. Knud pulled it open and blinked out at a small blond-headed boy who introduced himself as Børge Ollendorff, Preben’s younger brother. Preben had told him about the meeting, and he wanted in. No, he didn’t go to their school and, yes, he was younger by a year, but he hated the Nazi swine as much as any of them, and he hated Denmark’s official response even more. He stepped past Knud and tossed a bulging tobacco pouch onto Jens’s table. Help yourself, he said. He was willing to bring the club a steady supply from his dad’s tobacco company. That was powerful. Knud closed the door and sat back down. Børge slid onto the couch.

KNUD PEDERSEN: That afternoon Jens laid out a plan for our club—the model turned out to be very much like professional resistance units later in the war. Even though there were only a few of us to start with, we would divide our work into three departments: propaganda, technical, and sabotage. In time our organization would grow.

The propaganda department would paint up the city of Aalborg with anti-German messages to show that resistance was alive. Since we had no stencil machine or mimeograph to reproduce flyers, our first weapon would be paint. We chose the color blue. Striking quickly from our bicycles we would smear the damning word vaernemager—which meant “war profiteer”—on the stores and homes and offices of Danes who were known to be Nazi sympathizers and then pedal away like hell. We would expose them.

We made up our own insignia that day, an imitation of the ridiculous Nazi swastika. Our tilted cross had arrows shooting out of the top of each arm, like thunderbolts. “Here is the symbol of revolution against the Nazis!” our lightning bolts proclaimed. “This flame of rebellion kills Nazis!”

We would apply our trademark blue messages to the polished black German roadsters that lined the streets. We would add cheerful streaks of blue to the drab German barracks and headquarters buildings. Our insignia was also a death warning to the four chief Nazi war criminals, Hitler and his three top henchmen, Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, and Joseph Goebbels.

The technical department would produce bombs and other explosives. We vowed to do serious damage to German assets in the city, especially the railcars filled with airplane parts. We would wipe away Nazi smugness and awaken the Danish people.

In Mogens Fjellerup—nicknamed “the Professor”—we had a unique asset for the technical department. He was so brilliant at physics that the school had given him a key to the physics lab. In the coming weeks and months the Professor would steal heaps of chemical materials to combine into explosives. We nervously took turns helping him mix the ingredients. He spent a lot of time concocting nitroglycerine for bombs. Once he actually spilled the components during a meeting. It was very lucky for us it didn’t explode. But we knew we needed weapons, and until we could steal an arsenal we would have to make some of them ourselves. The Professor was the man.

Churchill Clubbers and friends in front of the monastery. Back row (left to right): Eigil, Helge, Jens, Knud. Front row (left to right): unknown, Børge, unknown, Mogens F.

The sabotage department would conduct the on-the-ground field work of the Churchill Club. Of course by being in that room on that day, everyone pledged to commit acts of sabotage—mainly destroying the Germans’ assets and stealing their weapons. I naturally gravitated toward sabotage work. I was inclined toward bold action. Jens was more of a planner, though a very brave one. I wanted to make problems, while he wanted to solve them. There was a fair amount of friction between us; we competed at everything.

After heated debate during our first meeting, we also decided to form a fourth section, which we named the passive department. This would consist of schoolmates who were not willing or brave enough to attack in the field but who could help us in other ways, such as raising money or developing support. For example, one classmate was the son of a paint manufacturer. In the coming weeks, once we had really gotten going with propaganda work, this student mentioned in casual conversation that the police had visited his dad’s factory seeking a match between the blue paint being slapped all over Aalborg and the company’s products. I took a risk and told him about the Churchill Club. I invited him to join. He declined, but he said he’d like to help us. After that he gave us all the blue paint we needed in ten-liter batches. Before long we had ten passive members in all.

We knew that every time we took in someone new, we would risk exposure. But we felt we had to take calculated chances. We needed people.

We concluded our first organizational meeting by agreeing to a few general principles:

• No adults must know of our activities. We would trust only each other.

• No guns in the school—that is, if we ever got any.

• Anyone who mentioned the name of the club to an outsider would be immediately banned.

• And, finally, the most important rule: To be an active member of the Churchill Club one had to commit a serious act of sabotage such as stealing a German weapon.

The reason for the last rule was simple. One who got caught stealing a German weapon stood a good chance of being executed. Risking this, everyone would have a serious investment in the club’s work. This rule would discourage anyone from telling authorities about the club because that person, too, would be incriminated. From a legal point of view, we would all be guilty together.

We would continue to meet after school in Jens’s studio. We would begin by taking roll and then go out on patrol. We’d divide the city up into sections, patrol on bicycles, and meet back at the monastery to discuss opportunities—then strike if we had anything. We would become daylight-crime specialists, since most of us had family curfews and couldn’t be out past dark. No problem—everything was guarded more closely at night anyway. The enemy was vulnerable to daytime strikes. And if we needed to work at night, we would tell our parents that we had formed a bridge club. We could say we were going out in the evening to play cards at the home of the only one of us who didn’t have a telephone.

As darkness gathered outside the monastery walls and the hour grew late, I got up, pulled the chair from the door, and said goodbye to my new mates. Today we were born. Tomorrow we would act.