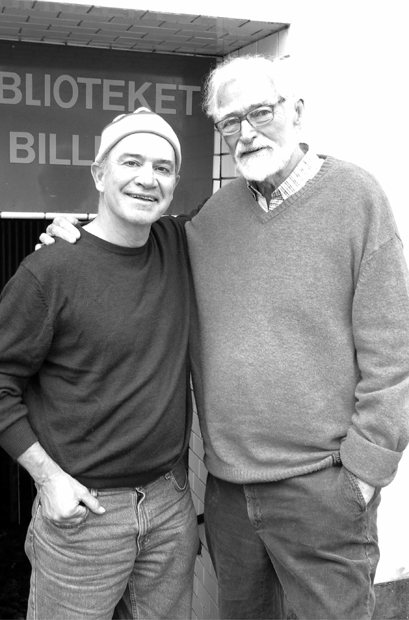

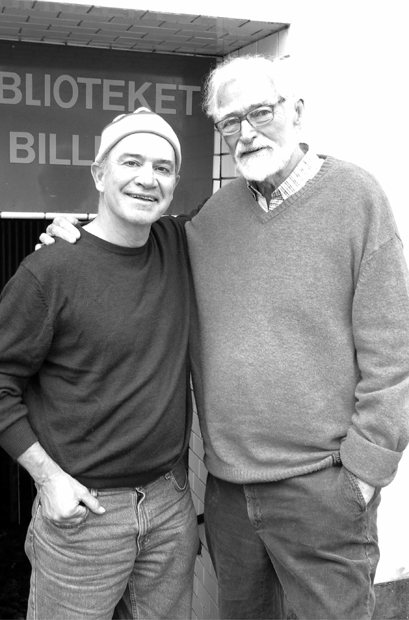

The author (left) with Knud Pedersen outside the Art Library in Copenhagen, 2012

In the summer of 2000 I took a bicycle tour of Denmark. On the final day I visited the Museum of Danish Resistance in Copenhagen, the nation’s capital. German forces had occupied Denmark between 1940 and 1945, and the Danes are known for having put up a staunch resistance to their occupiers. One of the most dramatic episodes in all of World War II was the famous Danish boatlift of most of the nation’s Jewish population to Sweden in late 1943, just before German forces could round them up and pack them by rail to death camps.

But what isn’t so well-known is that resistance in Denmark took quite a while to get off the ground. Exhibits at the museum showed that for the first two years most Danes felt hopelessly overwhelmed by the German Goliaths. They kept hope alive by gathering in public spaces to sing patriotic Danish songs or by purchasing “King’s Badges,” pieces of jewelry that identified the wearer as a proud Dane.

Then I came upon a special little exhibit entitled “The Churchill Club.” With photos, letters, cartoons, and weapons such as grenades and pistols, the exhibit told the story of a few Danish teens, schoolboys from a northern city, who got the resistance started. Mortified that Danish authorities had given up to the Germans without fighting back, these boys had waged a war of their own.

Most were ninth-graders at a school in Aalborg, in the northern part of Denmark called Jutland. Between their first meeting in December 1941 and their arrest in May 1942, the Churchill Club struck more than two dozen times, racing through the streets on bicycles in well-coordinated hits. Acts of vandalism quickly escalated to arson and major destruction of German property. The boys stole and cached German rifles, grenades, pistols, and ammunition—even a machine gun. Using explosives stolen from the school chemistry lab, they scorched a German railroad car filled with airplane wings. They carried out most of their actions in broad daylight, as they all had family curfews.

The Churchill Club’s sabotage spree awakened the complacent nation. One photo at the museum showed eight boys standing shoulder to shoulder in a jail yard, all but one holding up a number as a guard looked sternly on. Another snapshot captured the boys posing in front of an ancient monastery, identified as their headquarters. They looked cocky and innocent; one was smoking a pipe. A few were clearly some time away from their first shave. This group of students looked like the last people you’d expect to risk their lives in daring raids against Nazi masters. That charm was surely part of their power. You could imagine them running errands for freight-yard guards to soften them up.

The museum curator said a few of the boys—now old men—were still alive. Knud Pedersen, he said, was the best-known and most knowledgeable of the survivors. He ran an art library downtown. The curator wrote Mr. Pedersen’s e-mail address on a business card, which I tucked into my coat.

A week later, back in the United States, I fished out the card and wrote a message to Knud Pedersen. I wondered if the Churchill Club story had been written in English.

Mr. Pedersen’s reply came within hours:

Dear Phillip Hoose,

Thank you for your interest in the story about the Churchill Club … but unfortunately a contract has been signed with another American writer … I am sorry that I’m not in a position to help you.

So that was that. Someone had beaten me to the story; it wasn’t the first time. I printed out our e-mail correspondence, tucked it in a file, and forgot about it for more than a decade.

* * *

Fast-forward to September 2012. I was between books and looking for a new project. Rifling through old papers, I came upon a little manila folder labeled “Churchill Club.” Inside I found the long-ago exchange with Knud Pedersen—among the first e-mail messages I had ever written or received. I wondered if he was still alive and in good health. I also wondered if the other American writer’s book had ever been written. It seemed like something I would know about if it had. I jotted a reintroductory message to Knud Pedersen at the ancient address, pushed the Send button, and turned off the laptop for the day.

The following morning a message from Knud Pedersen was waiting: the other writer had not come through, he said. Now he was free to work with me. Immediately. “When can you come to Copenhagen?” Knud wanted to know. I glanced at my calendar and typed, “Oct 7 to 14.” Seconds after I’d sent my e-mail, you could almost hear his reply rocketing across the Atlantic: “My wife, Bodil, and I will meet you at the airport. You will stay with us at our cottage.”

I booked the flight.

* * *

Two weeks later my wife, Sandi, and I were met at the Copenhagen airport by a white-haired man, half a head taller than anyone else in baggage claim, and his wife. Knud dressed with the dash of an artist. Though we were jet-lagged, he drove us immediately to the Kunstbiblioteket (Art Library), which he had founded in 1957. The library is a below-street-level warren of rooms, some of which contain hundreds of paintings, kept off the ground in wooden racks. For a small lending fee, a patron can take out a painting for a period of weeks, just as one can take out a book at a library. If the borrower falls in love with the painting, he or she can buy it for a reasonable price—the artist has already agreed to sell it. The Art Library stems from Knud’s firm belief that art is like bread, an essential ingredient for nourishing the soul. Why should paintings only be available to the rich? And so he started this modest underground library. It was the first art library ever created, now beloved in Copenhagen and world-famous.

While Bodil and Sandi went off to see some local sights, Knud wanted to get right to work. We pulled his office door closed and settled into chairs on opposite sides of a desk. I placed a recording device on the center of the desk and turned it on. We barely budged for the next week—I got very used to Knud Pedersen’s face, and he mine. In all we spoke for nearly twenty-five hours, pausing only for meals or to take a walk.

Since I remembered just a few Danish words from my bicycle tour so long before, we had to rely on Knud’s English. Knud is a fluent speaker, but conducting a weeklong conversation in his second language clearly fatigued him. Still, he never complained.

That week Knud told me the story of middle-school students who refused to surrender Denmark’s freedom no matter what the country’s adult leaders did or said. German warplanes buzzed Denmark on April 9, 1940, dropping leaflets informing Danes that their nation had just become a “protectorate” of Germany. The German occupation was presented to Danish authorities as a choice: Comply, give us your food and transport system, work for us, and we’ll leave your cities standing. You can continue to police and govern yourselves. We’ll even buy materials and goods from you. You’ll make money. You’ll learn to like us. And after the war you’ll share in a glorious future with us. Or you can resist and be demolished. Denmark’s king and political leaders accepted.

On the very same day, Germany invaded Norway. Unlike the Danish, the Norwegians fought back early on. When Hitler demanded that Norway surrender, the Norwegians officially replied, “We will not submit voluntarily: the struggle is already in progress.” Skirmishes erupted throughout the Norwegian countryside and at sea. Germany captured key Norwegian ports and cities, but the Norwegian army kept fighting, moving inland to take up positions in Norway’s rugged interior. Losses were heavy.

As these events transpired, fourteen-year-old Knud Pedersen, a lanky schoolboy growing up in the industrial city of Odense, Denmark, experienced deep emotions, some for the first time. He was at once outraged by the German invasion, inspired by the Norwegians’ courage, and ashamed of the Danish adults who had taken Hitler’s deal.

Knud and his brother Jens, a year older, gathered a group of boys around them and vowed to fight back—to achieve what they called “Norwegian conditions.” When the Pedersen family moved to a different city, Aalborg, Knud and Jens organized a new group of brave and like-minded classmates to perform acts of sabotage. While most students were oblivious, these few stormed the streets of Aalborg on their bicycles to try to even the score. They called themselves the Churchill Club, after Britain’s leader Winston Churchill, whose fighting spirit they admired. The German occupiers, first annoyed and then enraged, called for the speedy arrest and punishment of whoever was stealing their weaponry and destroying their assets. Move fast, they warned Danish authorities, or the Gestapo will take over police functions. The chase was on. The events, which became widely known, awakened and inspired Danes everywhere.