Batman Again

“You have to take risks. We will only understand the miracle of life fully when we allow the unexpected to happen.”

— Paulo Coelho

In my early twenties, I tried to gain new outdoor skills by simply multiplying time in the field. But I noticed I was mostly gaining experience through all the slip-ups I had to rescue myself from. “Live and learn,” as the old saying goes. I definitely learned about prevention the time I paddled the entire Highland Creek from Highway 401 all the way to Lake Ontario in a minuscule toy rubber dinghy — during spring flood. That was a wild ride to be sure, especially the last half with my finger plugging up the hole created by smashing into a floating hawthorn tree. One needs a patch in those situations.

Long before the advent of modern mountain bikes, my best buddy and I built ourselves some trail bikes using old newspaper delivery bicycles, to which we had welded the low gearing from some children bicycles. We covered a lot of ground on those contraptions and were many times stuck out in the middle of nowhere with flat tires. I wonder today why I didn’t carry a patch in those situations either; I no doubt enjoyed the challenge of being in a jam out there.

1973. The first mountain bike?

It was when I was standing up in a toboggan zipping down a steep ravine that I learned that bones do break. And skis break too, as I found out on the sixth day of a winter camping trip around Algonquin Park’s longest hiking trail. With four days to go, I managed to switch the binding to the front half of the broken ski, but when the half-ski broke in the middle again, the only way to continue was to build a primitive homemade replacement from a maple branch. A patch doesn’t help here; one needs a full-fledged repair kit.

I suppose it’s only after flipping the canoe in rapids and losing stuff downriver a few times that one learns to tie in the gear properly. At least that’s how it worked with thick-headed me.

I’ll stop here, simply to maintain my shame at an acceptable level. There were countless mistakes. Chalk up one thousand to experience!

Okay, one thousand and one. At Taylor Statten Camps, I had been asked to start a bow-drill fire in front of the council ring of over three hundred people. To impress the gallery, I had the brilliant idea of pre-filling the notch in the board with burnt wood powder, figuring I would then only have to spin the drill enough to create an ember; I had glorious visions of fame from my would-be record-breaking speed. To make a long story short, the effect was opposite. The cold wood powder completely prevented the formation of the ember, so I was left there without a fire and without a place to hide my head in shame. This humbling experience really ticked me off, and for the rest of the summer, fuelled by that powerful substance called ego, I practised fire by friction with every possible variant — all species of hardwood, left handed, even blindfolded — until my fingers holding the bow string taut had developed thick calluses. On a positive note, at least the knowledge and skills gained by all of these blunders became impregnated in me, as I paddled, hiked, climbed, skied, snow-shoed, biked, and camped my way to becoming an outdoor professional.

In my mid-twenties, during my graduate school years, I also sojourned in Third World countries to broaden my survival skills horizon. My first major trip was to Africa’s Niger in the Sahara desert, then the second poorest country in the world, where I spent nearly two months with the Hausa and Touareg people. A food and outdoors background had landed me a job in an international cooperation project with the responsibility of documenting local food habits and survival techniques. During this life-changing experience, not only did I acquire specific skills like starting a fire with millet stalks with the hand-drill technique, or weaving mats and hats from palm leaves, but I also experienced a major sand storm and was able to join a camel expedition. Other travels included adventures such as hiking across Haiti and witnessing mind-bending voodoo ceremonies, hiking to a remote mountain village in India with a local doctor to spend a few days with a tribe that had never laid eyes on a white man, or going deep-sea fishing in the Bay of Bengal on a wooden sailing raft built from logs. What blew my mind during that experience was that these fishermen would actually wedge a perpendicular plank between the logs so they could trapeze while sailing.

Another memorable adventure was descending Costa Rica’s Tortuguero River via dugout canoe in cozy proximity to crocodiles. A highlight of that trip for me was one night when the local guide jokingly dared me to catch one of the reptiles as we spotted the red glow of their eyes with our lamps. In a flash I had pulled a snare out of my pocket, tied it to my paddle, and hoisted a four-footer into the pirogue. Somehow the noose had only hooked it by the snout, and we had quite a time trying to return it to the water as it trashed about and snapped at our feet.

Leaving for deep-sea fishing and sailing on the Bay of Bengal.

By the time I had completed my doctoral degree course work, my curriculum vitae had also been enhanced by a third year in a high school classroom, this time as a replacement science teacher. In reality, all I remember of that stint was getting the students on my side by letting them experiment with distilling moonshine, but it looked good on paper. My employment as a nature guide receiving groups of school kids at the Claremont Conservation Area also bolstered my teaching resume. Because of all this and flattering letters of recommendation I had obtained from former employers, project supervisors and graduate school staff, at the age of twenty-eight I was offered a job as professor of outdoor pursuits at the University of Quebec’s Chicoutimi campus. Nice way to pay off my student loans, I thought. At the time, little did I suspect I would spend my entire career there.

I admit I was just as delinquent a young professor as I had been a secondary school teacher. I recall one incident at Thornlea High School, where during a karate demonstration in the middle of math class I had inadvertently kicked a hole right through the plaster board wall, sending the entire bookshelf in the next classroom crashing down and just missing the stuffy old history teacher. “A demonstration in leverage gone wrong, so sorry,” I justified. And sorry I was too at my first university department meeting, when a roomful of straight-faced faculty members witnessed me fall backwards over my padded armchair as I exaggeratedly fidgeted and rocked from boredom.

Most students loved me though, especially the gifted, who appreciated my unique way of questioning the status quo. They would repeat my favourite advice: “Don’t let university interfere with your education!” And most of all, we had f-u-n, in and out of class. For example, every day they would hold the doors open and dare me to break my own record as I donned my mountain bike and helmet and rode from my office, down four sets of stairs, and then straight outside. In class they appreciated my trust as I would give them all A’s from the outset and then ask them to earn it. This actually worked; too bad the dean didn’t agree with my unusual methods and forced me to change.

The first couple of years at the university were spent struggling to complete my doctoral dissertation. Once that was out of the way, I felt it was time for creative pedagogy.

“What do you mean I can’t teach my outdoor leadership course in Mexico? It’s too late, all the students have already financed and bought their tickets and we’re leaving next week on our caving expedition!”

“The University’s insurance program doesn’t cover out-of-country activities, and besides, you didn’t advise me of this project ahead of time.”

“I didn’t realize I had to.”

“Hey, I’m the department head!”

“Okay, I guess I should have informed you of this. Didn’t know. What do we do now? The students have worked for the last three months preparing for this course.”

“Well, I simply cannot authorize this departure. Sorry.”

I left the stark-faced encounter pondering the value of my delinquent ways. Damned insurance! If it weren’t for this detail, the department head would never have found out about the trip and we would have been free to leave. I couldn’t cancel; the students would kill me. Three full months of planning and research. I was sure I had thought of everything. There hadn’t been a word about insurance in Colorado when our botany professor took us on a field trip. Why was I in this mess now? I barged into the dean’s office, while calling out to his secretary: “Emergency!”

The dean heard me out, but couldn’t or wouldn’t do anything for me. Stupid politics! Off I went to the vice-rector’s office. He was in a meeting somewhere. I convinced his secretary to squeeze me into his schedule the next morning. I went home to ponder. I pulled out the dossier I supervised, where the students had laid out in great detail the logistics and the security procedures. I read it one last time, satisfied. The next morning I met the vice-rector, dressed in my only suit — my politician costume — and charmed him into submission by emphasizing the fact that our role is to support the students in their endeavours and citing examples from other institutions. Being open-minded, he immediately acknowledged that I’d done my homework and thus agreed to take it upon himself to personally support the trip and to make the arrangements for insurance. I left in disbelief, relieved.

A week later we landed in Cancun, a world-renowned tourist trap. I knew we had to get out of there quickly, or my students would lose the feeling of disorientation I was trying to create. We immediately squeezed onto a local bus headed for Puerto Juarez, a small native village away from tourists. I could tell by the eleven students’ faces that they were overwhelmed by what they saw. I too was weighed down by the trip. It was only my seventh time in Mexico, mi Espagnol no es bueno, and I felt extra pressure to make this adventure successful. I booked us into some local hotel for less than ten bucks per room. After a supper of tortillas and bananas, safe food, we crashed for the night, exhausted by the journey. The next day, under student leadership this time, we bussed to the town of Mérida, where we visited the university and museum. Then we bought hammocks and camping food for a few days. Secretly I bought a devil’s mask I spotted in a stand; it would come in handy down deep in the caves.

When the roosters woke us the next mañana, we visited the archaeological ruins of Uxmal and then took a stuffed chicken bus to Villahermosa. There the students hired a local guide to walk with us to the entrance of the Cuevas de Xtacunbilxunan, near Bolonchenticul de Rejon, where we camped by stringing up our brand new hammocks between thorny trees. We also arranged for the guide to cook up a whole piglet barbeque for our supper. We partied sin cerveza.

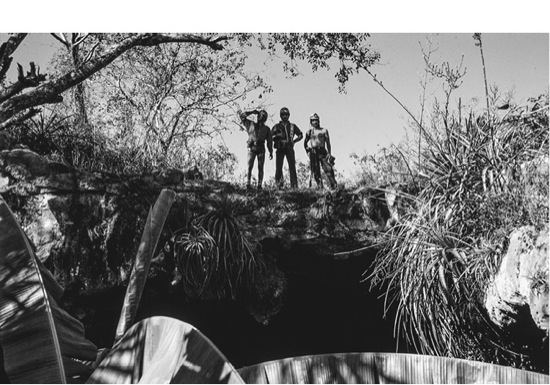

The strident yell of monkeys woke us just as the sun illuminated the incredible entrance to the wild caves. I pulled out the old caving guidebook unearthed through inter-library loan. It appeared no one had visited the particular cave we wished to explore since 1973. The main attraction was the underwater lake at the end of a two-kilometre long passageway. I picked that particular cave because it harbours but a single passageway, so there was a reduced chance of getting lost. The lake sounded neat, and most of the students were quite excited at the prospect of swimming in an underwater cenote. Eight decided to partake in the adventure. The other three — more tourists than too-risks — would watch our campsite. We tossed the packs brimming with climbing gear and lamps onto our backs and headed for the entrance, which came into view exactly where the guidebook said it would. So far so good.

Our first obstacle was to rappel down into the dark abyss. I went first with a powerful headlamp and reached the end of the rope before I touched the ground. I tied myself to a prusik knot and then looked down. False alarm, the ground was only a half-metre below me. I jumped, then slid five or six metres down a scree slope to a flat area. I whistled up for the next person to descend.

The entrance to the Xtacunbilxunan caves.

The eight students with me were all adventurers in their own right. They could take the pressure. So I decided to have a bit of fun at their expense. When the next student reached the end of the rope, I was way below him. I yelled at him insistently to jump, which of course he wouldn’t do since he thought it was a long drop. After letting him hang uncertain for a while, I climbed up and touched his feet, telling him it was a joke. He hopped down with relief. Then there were two of us to tease the next guy, and the last person was greeted at the end of the rope by eight loud summons to jump down into the non-existing void.

The student leaders that day had asked me to act as front-runner. We entered the creepy hallway and progressed through several chambers until we were back to a narrow passageway. At its end, another stalactite/stalagmite filled room, and another beyond. Several bats hovered in both. I was Batman again. The students took a pause. I told them I’d go ahead to answer nature’s call. I didn’t go back. Instead I put on the devil’s mask and hid behind a low rock with just my head sticking out. As the student leaders came forward calling my name, I flashed my light onto my face. More fun.

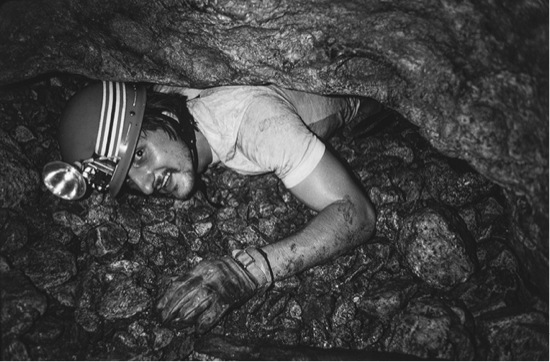

Finally we got to the entrance of the narrow artery that lead to the lake. The passage reminded me of the squeeze hole I had experienced in the Missouri cave, but not nearly as tight. It was still quite low and we had to crawl on hands and knees to get by. After twenty minutes, the passage swooped lower so we had to pull ourselves along with nothing but our elbows. At least the ground was soft and mushy. Time passed. Still no sign of the lake. I forged ahead, followed by my brave students. We crept along until finally feeling the humidity and coolness of the approaching lake. Then we heard it. An eerie shrieking sound.

It was bats — thousands and thousands of them. All gathered at the underground lake, probably their only water source. As we approached they got excited and moved in huge swarms. It was one of the most powerful displays of nature I had ever witnessed. We all listened in awe, but the students expressed concern. I shoved myself forward some more, sensing the lake was just there, a couple dozen metres away. The bats were more and more aroused, as they obviously could detect our presence. Some bats were coming toward us. It seemed like the path we were going through was their only way out. And all of a sudden, they ALL wanted out. A continuous flow of bats filled our narrow passageway, striking our hardhats and our shoulders as they flew by.

The passageway to the underground lake.

“There’s one in my shirt!”

“Me too!”.

“Just keep your heads down, guys, it can’t last long!” I replied.

After a few long minutes it was over. We walked to the edge of the lake, which was nothing but a mucky, dirty hole. The stench was unbearable.

“Let’s get out of here!”

The crawl back out suddenly became painfully disgusting, as we realized the reason for the soft ground below us. Guano! A lush carpet of bat excrement!

Needless to say, only fresh air and a good cleanup could transform us into happy campers again. Happy campers with new stories to share.

The rest of the trip remained rather uneventful, probably because we didn’t see any jaguars when we hired a guide to take us in a motorized dugout to “hunt for tigers” in the jungle near the Belize border. We finished our Yucatán tour with a bit of wonderful snorkelling on the barrier reef, then too soon we were back in Canada.

A few days later, I was soaking my sheets with fever. Never had I been so sick. But after a couple of hours had passed I was just fine and commuted to the university. By lunch I was back in bed, with incredible fever and headaches again. At suppertime I felt okay. Then came night chills followed by more menacingly high temperatures on the thermometer. Weird, powerful flu-like symptoms appeared and disappeared suddenly. The doctor brushed it off. After all, I looked perfectly well when I went to the clinic. In another hour, I was totally wiped out again.

When I went back to the university the next day, between two spells of fever, I met a couple of my students who reported the same symptoms. A few phone calls later, I deduced that only the eight students that had been in the cave were affected. I ran to the library and pulled some medical books off the shelf. Looked up bat diseases. There were two. Histoplasmosis, sometimes deadly in old or weak persons, and coccidioidomycosis, often deadly. Oh my God! I jumped in the car and headed back to the clinic. Without an appointment, I saw a different doctor. This one witnessed me in fever mode and I asked him to test me for histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis. The x-ray showed completely white lungs. He was most impressed, showing it to the other doctors. None of them had seen this before. Scary moment.

Turns out we were affected by severe histoplasmosis. Histoplasma fungus lives on bat guano and we had breathed in the spores, which later grew in our lungs. We were ill for over two weeks before the symptoms subsided. The slight consolation was that apparently we were immunized for life, although benign white scars would forever remain on our chest x-rays. Makes for good conversation with medical staff.

I never filed the final report for this trip. Blamed it on the flu.