“The worst risk of all is to not risk at all.”

— André-François Bourbeau

Réal Toupin patiently helped me regain my confidence. But it took five years before I dared to sing in public again, this time as member of the symphonic choir. I eventually learned that music has very little to do with performance. It is a tender gift you give friends. It seemed to me worthwhile daily occupations should be like music. At long last, I could abandon the search for recognition through exploits.

A while back I was invited to sing the Panis Angelicus at a service in Champlain. I said yes because the 1671 church there happens to be a National Historic Monument and it was built to naturally amplify unplugged voices. Plus, the incredible original organ still tosses notes way up to the vaulted ceiling. My rendition was far from being perfect, maybe not even good, but I gave it my soul to honour history. People smiled. Perhaps because I had finally become a musician. Or perhaps because the tuxedo I was wearing looked nice. No matter, it was a fantastic experience to time travel back to Champlain’s era.

It is certainly peculiar, this strange bird called Time, flying by so quickly, yet still managing to gently deposit the basket of maturity on our doorstep. With age and experience, we see differently, weigh things more accurately. But frustrating too, this gift of newborn wisdom, because we realize we only experimented with but a tiny fraction of the dreams we caressed while young. Alas! I came to realize that in a single life I could only scratch the surface of all the secrets nature had to offer. Good reason to pursue the crusade for wilderness protection.

There are occasions in life that remind us of our age. Like the first time a student called me Mister Bourbeau instead of André. Or worse still, the day one of my pretty twenty-year-old students exclaimed “Oh, Dr. Bourbeau, it’s so much fun being in the bush with you. You’re a bit like our grandpa you know.” Yikes!

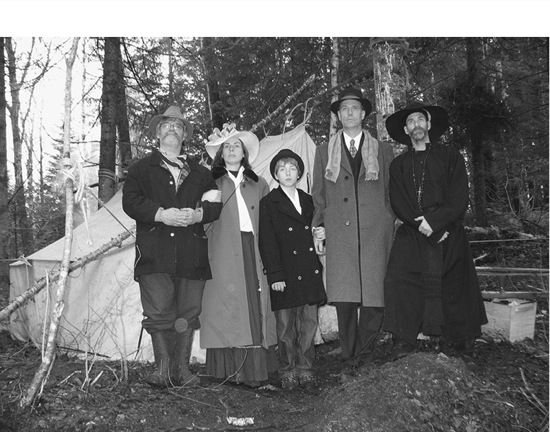

Well, I decided to push the grandpa idea to celebrate the last course of my university teaching career — traditional outdoor activities. I had opted for a gradual retirement plan, thus I had some time. I wanted to give my students and myself a final splashy special project, so I imagined a scenario where we were a bunch of farmers from Laterrière village who had been hired by William Price, Saguenay’s eighteenth-century timber baron, to go fetch two immense wooden beams for the construction of a church. Each of us had a name and a role in history, from schoolteacher to physician. I was the old granddad of the gang, a trapper.

I put the students in the mood by visiting Chicoutimi’s old pulp-mill museum, giving them copies of the newspapers of the era and circulating copies of the original 1895 Montgomery Ward & Co. catalogue. They would prepare their own costumes and personal gear. Oh, and the guys had to grow a moustache. They would also research their character, plus find a subject to teach the others. My assistants and I would take care of everything else: food, tools, group gear. We enjoyed eight months of adventure begging for all the old stuff we needed, or making it ourselves, or buying it. It cost me a fortune, both in time and money.

But what a neat voyage to the past we lived that November. Unknown to the students, I had convinced a friend to come with a giant draft horse and sled to carry the gear to the end of the bush trail. From there it was a bushwhacking portage to the camping site in a soon-to-be-cut forest, so we could freely chop all the wood we wanted. My assistant had planted a farm-raised deer in the forest and covered it with fake blood so he could go “hunting.” When we all heard the shot, I sent four students to go help him drag back the meat we would eat for ten days.

At first the men lived in a canvas lean-to. But after five days of axemanship, they were installed in a typical lumberjack camp, complete with central fireplace. The gals lived in a prospector’s tent, owned by the guy who had been to the gold rush, while the bosses had their own baker’s tent. As per tradition, we prayed every morning and every night, and said grace before each meal while gathered around the outdoor Chippewa kitchen. On Sunday we served mass in Latin, thanks to a colleague who donned the black robe and came to visit, with a choir to boot.

We felled a giant white spruce and squared it with broad axes, holding it steady with iron dogs made on the spot by the blacksmith of the group. Then we pulled it half a kilometre to the lake, using hemp ropes and wooden pulleys. For a final highlight, I had my old Retro-Propulsion-paddler Marcel disguise himself as Sir William Price himself. He was a terrific actor, English accent and all, as were his wife and son. By then we were so totally immersed in our roles that his arrival gave us all goosebumps, even me who was in on the secret. That night we partook in homemade bread, baked beans, roast deer ribs, and apple crisp, followed by a rousing sing-along led by the resident teller of legends. A wonderful end to a wonderful career.

Granddad with Sir William Price and family, and Father Tremblay.

When I retired, I was honoured with Professor Emeritus status, which means I’m allowed to continue working for free. Joking aside, it mostly signifies that I can continue my research while accessing the university’s resources. I suppose it also gives me the right and obligation to write wise conclusions in books. I’ll try. In fact, I’ll abuse my privilege and offer three.

For my first conclusion, I would like to discourse about risk.

I remain convinced that risk is worthwhile. The worst risk of all is to not risk at all. Risk defines adventure, and adventure defines life. To feel alive, one needs to push limits. To fall down sometimes.

But that doesn’t mean taking risks at all costs. There are good risks, but also stupid risks. Good risks are the ones whose result, if the danger materializes, make you suffer from blisters, bring you to the edge of exhaustion, make you wet and miserable, make you scratchy from mosquito bites, scare you to death while staying safe, cost you money by scrapping your gear, make you look ridiculous, or even shame you to tears. Stupid risks are the ones whose materialization kill you or maim you permanently, like losing feet to frostbite. I’ve taken a lot of good risks in my life, which made me grow stronger and made me a better person. I also flirted with many stupid risks, of which I am not proud — these I was simply lucky to survive. Those types of risks I will not take anymore. Nor would I suggest them to anyone. Life is just too sweet to waste it by accident.

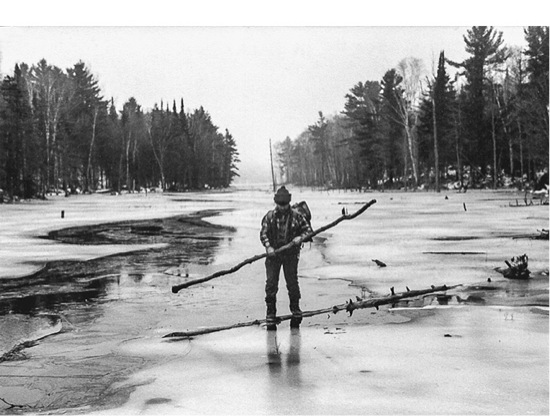

The joy of walking on thin ice.

Yes but, some will say. I know, I know, we risk dying every day in traffic. It’s the old risk-versus-probability graph. That doesn’t mean we should play ball in the middle of the freeway. Consider the historic difference in canoeing risk. After spending hundreds of hours building a birchbark canoe, the coureurs de bois thrilled in descending class 2 rapids, the consequence of which was having to start all over again after walking fifty kilometres back to camp. Good risk. Nowadays, with ABS canoes, that thrill is gone, because the boats are indestructible. So we move up to R4 and R5 rapids, where the chances of drowning are severe at the slightest mistake. Bad risk.

To help manage risks, I have found that it helps to consider four simple pessimistic scenarios before undertaking an adventure. What happens if I’m detained for a few hours for various reasons? In what kind of trouble will I find myself if I lose my gear, for example if my motor quits on me? Where will I get help if I’m badly hurt at the furthest point of my route? What are the consequences of a human mistake? If the answer is “I won’t like it cause I’ll suffer,” you may choose to proceed. But to the answer “I die,” I would strongly reconsider.

For my second conclusion, the discourse relates to wilderness survival.

Once we’re in trouble, my observations are that survival depends on four factors: physical capacity, psychological outlook, specific technical skills, and decision-making. And let us be aware that my own experiences have all been piddly compared to real survival situations. After all, I was doing this stuff voluntarily, and almost always had a way out. I was just playing. When we study real incidents, when life is truly at stake, survival takes on a whole different meaning. When bones are broken or guts are hanging out, we’re no longer talking macho. Survival is no fun then.

Of the four factors, physical capacity can be improved by increasing fitness level. My mantra on this one is simple: GO PLAY OUTSIDE. As far as psychological outlook is concerned, you have to love life. DO THINGS. It also helps to read real-life survival stories. When you do, it gives you examples of what others have been through, and if it happens to you, you have a reference point. Technical skills can be acquired through the long and narrow path of experience, but they are faster and more safely gained by engaging in simulations. TRY CHALLENGES. Enter the loop of try-fail-try-fail-try-fail-try-WIN.

But although these three factors are all fundamentally important, it’s often the decision-making that kills or saves. The study of close-call incidents and fatal accidents reveal this clearly. Over the years, with the precious help of my colleagues at the university, I have developed a tool for thinking straight when caught in a wilderness survival predicament: the SERA model.

SERA is an acronym for Search-and-rescue, Energy, Risk, and Assets. The key to survival is to always stop and consider the impact your decision will have on each of these four factors before action. THINK SERA BEFORE ACTION. Qui sera sera. Whoever will be (thinking sera) will be (sera) alive.

KEY POINTS FOR SURVIVAL IN THE WILDERNESS:

S – Help Search-and-rescue teams to find you

E – Conserve your precious vital Energy

R – Minimize Risks

A – Pamper your Assets

In concrete terms, this translates to preparing signals and staying in open spaces, immediately switching to slow-down-and-save-energy mode, avoiding all further perilous acts, and taking precious care not to lose or otherwise destroy or damage the gear available.

The SERA model’s role is to prevent foolish immediate action (panic), which is perfectly natural in a stress context (let’s get the hell out of here or let’s do something about this right now).

For example, your snowmobile breaks down, it’s ten below zero Celsius with wind, early evening, forty kilometres from camp. One option is to build a Quincy snow house. Stop. Think SERA. S. Inside a Quincy, I will not hear the search-and-rescue snowmobile go by. Negative. E. It takes a lot of energy to build such a shelter, but I will save energy fighting cold once built because I will be out of the wind. Neutral. R. If the Quincy caves in on me while building it, I risk suffocation. Negative. A. Right now my clothing is dry. Once the Quincy is finished, they will be at least partly wet, both from snow and from sweat. Very negative. Hmm, maybe a Quincy isn’t such a good idea after all.

Another option is to start walking out along the snowmobile path. Stop. Think SERA. S. Positive. E. Very negative. R. Very negative, hypothermia and frostbite if I don’t make it. A. Negative, clothing will get damp. Better forget that idea too. So I just slowly dig a hole behind my machine to get out of the wind and wait, doing calisthenics as need be to maintain slight warmth.

My third and final conclusion does not refer to wilderness survival but rather to survival of the wilderness.

It was gently snowing last October as I was standing on the shore of the heart-shaped lake where the helicopter had dropped us for the Survivathon. Yes, roads now permitted me to drive my van way up into this formerly wild territory. But I couldn’t recognize the spot where I had lit my magical fire a quarter of a century before; the forest was no longer, it had fallen to clear-cut logging. Although I understand the economics of forestry, which can be viewed as agriculture spanning sixty years, and know full well that forest eventually rises again, I could not help but feel a certain pinch faced with the desolation before me. This made me question the qualifiers “progress” and “development” to justify human gluttony.

I am often asked if I would repeat my Survivathon or other adventures. Of course not. I’m not a masochist. But if I could go back in time and was permitted to choose again, I would not hesitate a single micro-instant. Because there are no words to describe the raw power of this intimacy with nature. It is like watching a child grow. What emotions! And just like a mother forgets the pain of childbirth while she later admires the eyes of her growing baby, I have long forgotten the labours I lived through and only my soft regards for tender nature remain.

The value of a passionate relationship with nature cannot be expressed, just like a picture can never bear witness to the smell of flowers, the sound of a creek, or the feel of the wind on our faces. We have to be there. And when we do sense this great Cathedral of beauty which combines both complexity and simplicity, peace seeps into our pores. And we care.

This is why I invite young and old to play “wilderness survival.” Each fire, each tasted cattail, each sip of water drunk from a bark cup, and each wiggling trout on the hook adds perspective to our soul — necessary in a modern life that artificially chops us off more and more from our origins.

In my years of teaching outdoors, I’ve had the opportunity to observe many expressive faces: wonder at the appearance of a first ember by friction, satisfaction when lying on a successful park-bench, pride as the slingshot stone smacks its target, surprise when birchbark ladles mirror in water, sweet smiles when the log raft floats away in the mist. Then, several years later, it is with contentment that I admire these same faces — aged a bit, mind you — in positions of leadership in a variety of roles in society, but always imbued with a common interest in protecting nature.

It is probably my mentor, the late Kirk Wipper, who best expressed my thoughts. “You have to do what you can, do your best with what you are. And you have to believe in wilderness. If you do that you can’t go wrong.” So, as a tribute to Kirk, I would like to raise a point that I believe is fundamental to the survival of the wilderness. I call it the construction disease: the uncontrollable mania of the human being to build and develop, at any expense, justified by all kinds of pretexts all allegedly greater one than the other. Thus, we see the proliferation of new forest roads, trails, hunting vantage points, cabins, chalets, lodges, dams, and so on. Armed with chainsaws and more and more efficient all-terrain vehicles, forest tourists mow their way to each lake or pond until they can access it by motorized means. Once the trail is constructed, they install basic comforts. But in no time they require fridges, stoves, and then television. In short, they have moved the entire city to the forest. Thusly, nature and wild spaces gradually disappear. The construction disease fiercely attacks — even in the supposedly protected territories called parks, customer demands force administrators to develop additional infrastructures.

The construction disease also infects cities. Saguenay has at least doubled its surface area in the last two decades, without increasing its population. Where we once saw nature with buildings here and there we now see buildings with nature here and there. In my immediate neighbourhood, the last thirty years has seen emerge a factory and countless houses built at the water’s edge, until there is now no place to camp. Even the agricultural zoning did not resist the onslaught of developers who easily received the rights to construct.

I have nothing against the construction industry. I see no harm in replacing an obsolete building by a new one, in beautifying a neighbourhood, in re-asphalting a road. What I question is this tendency to solicit new wilderness areas in the name of progress. This encroaches on nature, irreversibly destroys it. The result is that we are now surrounded by city, rather than by nature. No one can accurately predict the effect of this change on the quality of life of future generations. To eradicate the illness, I therefore vote for a moratorium on any new construction that impacts wilderness areas. One day, perhaps, annual development and progress will be measured by the number of buildings that have been removed to yield place to nature once more. I hope so.

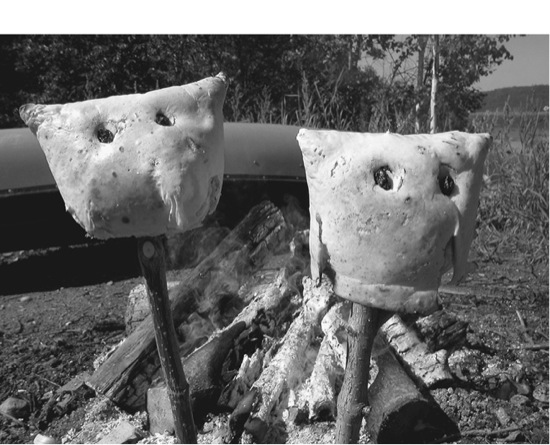

Bannock phantoms.

What’s next for me, I wonder? Last summer I paddled the entire length of the Horton River in the Northwest Territories all the way to the Arctic Ocean. Caribou, muskox, bears, big fish, good friends. I liked that. My mind is boiling with fun ideas. Hike the Pacific Crest and Appalachian trails. Sail the Great Loop. Canoe Mongolia’s rivers. Mountain bike the Continental Divide. Build another spruce-bark canoe and paddle it as a coureur de bois through Cree territory. Not for performance. But to leisurely enjoy simple, non-motorized travel. I will also surely pursue my research work — after all, research is the infinite final frontier.

And if one day my health limits me to strolling in the park, playing chess, doing the daily crossword puzzle, reading and playing in a band, perhaps I will sit down again to write another book concerning my new adventures. But until then, I’m off to the wilderness. Cause I’m hungry for more bannock phantoms.