The Farmer

“Adversity is like a strong wind. It tears away from us all but the things that cannot be torn, so that we see ourselves as we really are.”

— Arthur Golden

The van was jam packed as I sped along Highway 80 through Iowa and then Nebraska, on my way to Colorado to check out the worth of those impossibly steep tuition fees I had just dished out as a foreign student. My reverie of seeing the Rocky Mountains for the first time was suddenly interrupted by engine noise, which made me stop at a nearby garage. No way I was going to spend three hundred and fifty dollars to change a burned out valve on this old van! “How much just to grind the valve?” I asked. Five bucks sounded a lot better to me, so I found a vacant lot nearby and got to work taking that engine apart. Six hours later, I was in the possession of a freshly ground valve but the necessary new head gasket was priced at over sixty dollars. I did without. After spraying the old head gasket with a can of aluminum paint, I torqued the bolts and was off again, albeit with dirty hands. Twenty thousand kilometres later, I knew that paint had done the trick. The rest of the uneventful trip was spent reflecting on how any bit of practical knowledge can make a difference when facing a specific survival situation, be it to execute a mechanical repair, pick a lock, or even fly a plane. So much to learn!

Once at the University of Northern Colorado, among all of my classes I was really looking forward to the Outdoor Survival 508 course. I was dumbfounded when I found out who they had chosen as part-time lecturer — me. But I sure didn’t lecture much. Preferring to experiment, I would take fellow students out into the prairie woodlots without gear. There they tried their hand at such skills as friction fires, tool-making by breaking stones, sucking water from wild asparagus shoots, and fishing for carp with homemade spears. On one occasion we made a huge grass debris hut so all twenty-four of us could sleep in it. Cuddled up like spoons, we affronted the cold night by turning over and rotating every half hour. Only the two people on the ends had to shiver for their own thirty-minute stint.

Other than this one memorable occasion, my first year as a graduate student had proven uneventful, saddled with adrenaline-devoid classes such as Philosophy of Outdoor Education and Administration of Outdoor Education Programs. At least I developed wonderful relationships with fellow students who complained as I did of boredom, and our fun was found sharing rock climbing and mountain hiking adventures, which are Colorado’s state pastimes.

The twenty-four-person debris hut we slept in.

As I was about to graduate with my Master’s degree, I decided to imitate many of my buddies who were continuing at the doctoral level. It so happened that the University of Northern Colorado offered at the time a world-unique program called the School of Educational Change and Development, which permitted students to present a special doctoral project of their own creation. If I could convince seven professors to accept my project, it would become a signed deal. I proposed a plan that borrowed courses from a vast selection of the University’s existing programs that I felt would help me pursue my quest for survival knowledge. For example, I would delve into North American Indian lore in the history department, learn to flake stone tools in the lithic technology courses of the archeology program, study plants in depth through systematic botany, and learn to identify and work with useful minerals with geology students at my side. My plan also included trips to several Third World countries to study local primitive survival techniques; I would go off to Africa, India, and Central America. Finally, my doctoral program would be completed by conducting week-long survival experiments without gear in each of the four seasons, to personally test the panoply of techniques I would expose in my thesis. After many discussions and adjustments, the professors finally accepted my project and I became the school’s first doctoral student in the field of wilderness survival education. I felt honoured.

I kept journals of the four survival experiments I conducted. The first was in late October. The weatherman announced a warning of early snow, which would add to the adventure. Fine with me. I sure didn’t suspect it would turn out to be a record-breaking storm, dumping half a metre of fresh powder within a couple of hours.

“Hey Bill, you can drop me off here on this bridge.”

“Are you sure you’re going to be okay for a whole week? This blowing snow looks pretty bad to me!”

“Don’t worry, Bill, you know I’ve done a lot worse. Come and check up on me in three days. We’ll be able to yell at each other from the other side of the river where you usually drop me off. You’ll see, I’ll be in great shape.”

“You’re crazier than I thought!”

I headed to the confluence of the South Platte and Cache la Poudre rivers, about four kilometres away across some farmer’s fields. In no time I would be in the sheltered woods on the long point I’d camped at before. It would have been easier to get there by driving to the roundabout on the other side of the river and wading across, but the water was too cold at that time of year.

I headed east, using the snow blustering obliquely from my left to guide me. After two minutes hiking in ankle deep powder, the whiteout had erased the picture of the bridge behind me. I wasn’t the least bit concerned about direction finding, since I was standing on a point of land between two rivers; as soon as I reached either I would follow its shore to the confluence. So I pushed on.

The wind somehow seemed sinister, sending swirls of the white stuff to caress me like so many wispy phantom fingers. On the ground, any irregularities caused the snow to pile up into drifting banks. Soon I reached the edge of the field, where a drainage ditch filled with water stopped me. I followed this depression, hoping to find an easy place to cross, but to no avail. I spotted a fence and manage to pry loose one of its posts, which I used as a bridge. As I hopped across, the semi-rotten grey wood broke in half and fell into the water, but at least I avoided a soaking. I realized that I’d “burnt my bridge behind me,” finding the expression ironical in this freezing context.

In the short twenty minutes it took to fetch the fence post to cross the ditch, the snow had accumulated to just below my knees. The field I was crossing had recently been plowed, and the ruts rendered the walking treacherous. I slowed down, stressed by the thought of a sprained ankle. After an hour confronting the blizzard, I was no longer so sure of myself. Nature has a way of dealing with overconfidence. The drifts got up to a metre high, and my pace was ever-increasingly sluggish. Before I knew it, I’d slowed to a crawl, and I couldn’t see ten paces in front of me. My pants were soaking wet up to the crotch.

For this week-long experiment, I was carrying a few items, since I was pretending to be a seventeenth-century Métis travelling between two villages. Thusly, my equipment list included a pound of wild rice and an equivalent amount of animal fat stuffed into a tin can, a belt knife, flint and steel with tinder in a waterproof tin box, a one metre by half metre piece of fur, and the clothes on my back: leather boots, one pair of socks, cotton pants, underwear, belt, shirt, wool sweater, leather jacket, wool mitts, and a toque. I wore eyeglasses, a compromise I have to accept, as well as a watch. My pot, food, and tinder box were wrapped in the sheepskin, tied into a tight bundle with two leather thongs. Other than that, the only items I carried were a notepad, pencil, and my wallet, which would be needed when I got out of there the following week.

As the storm raged on, I was wasting considerable energy plowing through the drifts and fighting the cold’s attack, well aware that soon I would be in bad shape. I was no longer a happy camper, but I had to plug ahead. So I counted step sequences: one, one two, one two three, one two three four … Up to ten, then backwards to one. This helped.

After a few such sequences, the apparition of a huge willow tree became my first sign of progress and my first chance to take a break from the direct blast of the wind. I’d come to a corner, the intersection of four fields. There grew a total of four willow trees, all lined up. I unrolled my bundle, carefully pocketing the precious tinder box, and sat on the piece of sheepskin I’d draped over a protruding root. My survival experiment had degenerated into a real situation. It was time to assess.

If I continued on to the woodlot as planned, it had become obvious that I wouldn’t get there before dark. Plus, I would surely be dead tired, “toasted on both sides” as outdoorsmen say, and no doubt too close to deadly hypothermia for comfort. If I went back, my situation would be even worse; I’d be facing almost directly into the wind, I didn’t know if I could find a way to cross the ditch again without getting wet up to the waist, and even if I could find my way back to the bridge it would be a long walk along the gravel road to the first house in this deep snow. In such a predicament, I would counsel my students to “inventory your possessions and the environmental resources!” So I did. Apart from my short equipment list, I had tons of fluffy snow and four trees, the biggest one of which offered partial shelter from the wind. From those trees, the odd dead sucker shoots offered a bit of firewood, but barely enough to keep a fire going for an hour or two — certainly not overnight. How did I get myself into this mess?

As I shivered while contemplating the three ugly options, my stiffening pants enticed me to decide in favour of starting a fire right then and there. I cleared away the snow and started whittling some fuzz sticks from a dead branch. Soon the flint and steel coaxed them alive into dancing flames. The show was spectacular, the wind tossing those flames into somersaults. My smoky eyes shed forced tears of appreciation. At least my pants were drying!

In what seemed like mere minutes, the wood was gone and my eyes and lungs were sore due to the twirling smoke. But I was dry and I’d had a welcome drink of melted snow. I followed my tracks back to each of the willow trees to see if I could muster up more wood. After some prying, I managed to rip out one of the leg-sized sucker shoots that had previously resisted my efforts. Several other pieces of fuel fell prey to my eagerness.

As darkness fell, a last ditch effort to scrounge up every possible piece of firewood became necessary. I knotted my two thongs together and lengthened the improvised rope with my shoelaces and belt. Armed with this mini-lasso, a couple of low-lying branches were added onto the chaotic collection of firewood.

The pile remained tiny. There was no way it could keep a fire going for more than two hours, I estimated. Soft willow burns like paper, especially with a fierce wind fanning it as in a forge. Then what? As the last bit of daylight disappeared, I pondered why I was there, suffering like I was. Am I nuts? Crazy? I tried to convince myself that my experimentation was worthwhile, with minimal success. Then I took refuge in the fact that I’d always fed upon adversity. Like the old saying goes: “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger!” Though I didn’t like the alternative the saying suggested.…

With no choice but to spend the night, an idea emerged. I divided the wood into four equal heaps, which I reserved for half-hour fires at ten o’clock, midnight, two o’clock, and four in the morning. That way I figured I would be able to warm up a bit between stints of light calisthenics. I used one of the piles as a seat and two others I leaned on each side of the tree to break the wind, with limited success. The last pile I broke into manageable pieces and set-up tee-pee fashion. I reserved the driest and straightest piece to whittle into shavings.

Reality hit me hard: the drafts made me feel like I was dressed in a sieve. It was physical and mental torment just waiting until ten. And when the long-awaited hour finally arrived, the fire’s smoke just switched the type of pain from biting cold to eye and lung irritation. Agony. I couldn’t even manage to cook the rice I was looking forward to. The fire was simply too unmanageable and short-lived. Warming my bare hands on the remaining coals, I attempted to use the sticky snow from near the fire to widen my lone tree wind-break. Useless. I finally stomped out what was left of the embers to obtain the relief of a smoke-free environment. Pitch black and bitter cold once more.

It seemed like forever until midnight, and longer still until two o’clock. Excruciating. I couldn’t believe I volunteered for this. It was absolutely the worst night of my life. If I didn’t freeze to death, I swore the smoke would finish me off anyway. It was the wind lesson all over again. Definitely, unquestionably, categorically, undeniably, and without doubt, avoiding wind would forever be my absolute number one priority in any cold weather survival situation!

At four o’clock I entered the smoky torture chamber to get my eyes whipped for the last time. I was burning the wood underneath me, which had permitted lying in fetal position, and I was back to sitting on the crooked root. Nevertheless, the miracle of fire amazed me as always, and my toes welcomed the heat. In spite of an exhausted state, I felt overwhelmed by the grandiose spectacle of nature that surrounded me. Awe inspiring. What a privilege to witness first-hand how minuscule a lone man can be in the face of such power!

As if to acknowledge my revelation, the mean wind softened somewhat. I shivered until morning, but it didn’t matter anymore. I knew I would survive. As daylight broke on André the farmer lost in his field, some type of strange calmness overcame me. Perhaps to match the same calmness around me, for the wind had died down. The storm was over.

I reached for my eyeglasses, safely stored in the pot. My vision remained somewhat blurry. I wiped the specs with a corner of my shirt, to no avail. Then I realized I must be suffering from mild corneal abrasion. Another close call. If more firewood had been available, I would surely have been half blind that morning. And perhaps also severely ill from carbon monoxide poisoning.

After a few minutes of involuntary tears, I rolled up my bundle and tossed it onto my shoulder, happy to leave the horror show behind. In the far distance, I could guess the presence of the woods I was headed toward. Typical of Colorado’s instant weather changes, the sunrise pierced the few remaining clouds. It would be a nice day. My spirits lifted with the increasing luminosity, which highlighted the pretty blanket of fresh virgin snow. I savoured the spellbinding white beauty; a gift to compensate the previous night’s hardships. Nature’s dichotomy never ceases to amaze me.

I wove around the drifts, seeking the shallowest passage to my destination. Two harsh hours later, I finally arrived and immediately sought the comfort of a warm and cheerful fire — in a dense wind-free location. As the wild rice boiled, I sacrificed my leather thongs and started fabricating a pair of quick and dirty snowshoes in order to avoid having to dry my pants and boots each time I drifted away from the campsite.

After ingesting half my daily ration of calories, it was time to gather a substantial pile of firewood. Once that task was out of the way, I found two standing rotten trees of a fair size, which I pushed over and dragged back to the fire spot. Placed side by side a metre away from the heat, they made a reasonable bed for me to crash on. How sweet sleep is when one is so exceedingly exhausted!

My slumber was deep, interrupted only by the sporadic half-awake tug on the long logs to advance their sooty ends back into the fire’s heart. A few hours later, I was a new man. Well, comparatively new. Under such circumstances, the lack of comfort has always woken me too early, as if by an unwanted alarm clock.

I headed out for more firewood. When I thought I had enough for the night, I doubled the amount, and then doubled it again. My rule is twenty logs as big as I can carry per night, at least. After I accumulated a two-day supply, I made my way to the river’s edge where I wandered, on the lookout for soft and dry bedding material such as goldenrod or fireweed. Suddenly, a floppy object attracted my attention. Wow, it’s a lame duck! Supper! I pounced on it with the instinct of a wild cheetah, quickly putting an end to its misery. I’ve always hated killing animals, but I consider it an act of necessary evil. Nevertheless, I briefly regretted my decision. But my grumbling stomach convinced me to think otherwise. As I examined the bird, I could feel the shotgun ammo that brought it down. Some hunter’s bad luck. My good fortune.

I snowshoed downstream along the Platte River to the confluence, the mallard dangling from my belt, and started my way back to camp by going upstream along the Cache la Poudre River with the intention of circumnavigating the woods back to the spot where I had entered it. After a few hundred steps, I was stopped in my tracks by a shrill whistle that came from behind me. I turned around and went back to the point at the confluence to find Bill yelling from across the river.

“Wildman, are you okay? I was worried because of the storm. It was the worst in Colorado history!”

“I’m fine Bill. Thanks for checking up on me!”

“I see you made yourself some snowshoes. Should have known. Where the hell did you get that duck?”

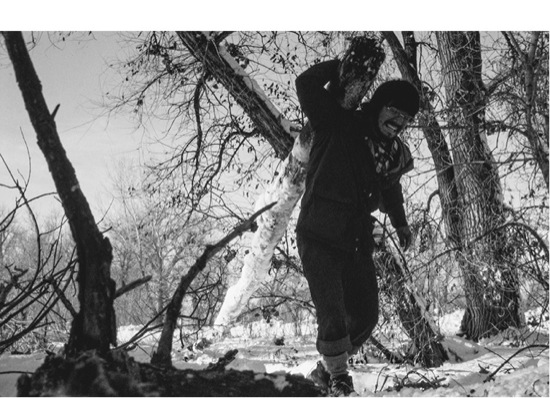

My rule is twenty logs per night.

“Caught it with my bare hands.” I didn’t tell him it was lame, of course. There goes my ego again, trying to impress.

“Unbelievable! You’re da crazy Frenchman!”

After some more small talk, since he announced the weather would be fine all week, we agreed that he would pick me up in five days at the spot where he dropped me off. Then he left as quickly as he came, a flabbergasted spectator in front of the magician who survived the storm of the century without the flinch of an eye. If he only knew of the pain behind the trick. His departure left me proud of my performance, yet so lonely in the knowledge of my deceit. It’s a tough price to pay for ownership of that super ego of mine.

As I sat calmly later that evening, toasty warm between the fire and the huge overturned log behind me, delighting in roast duck and wild rice, I thought of my dear old mom back in Scarborough, thousands of kilometres away, who in the face of adversity always maintains that after rain comes sunshine. You’re right, Mom!

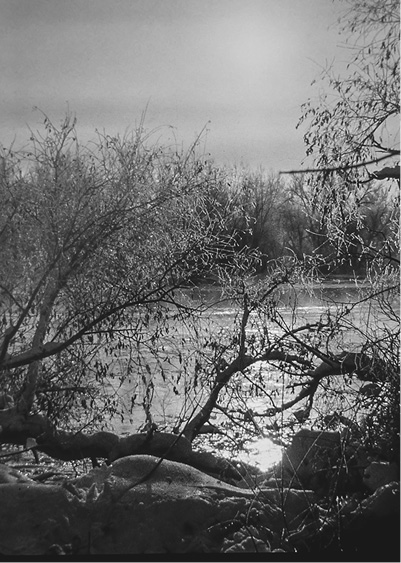

The South Platte River.

The rest of the week was rather uneventful, other than the loss of a couple of kilos due to short rations. The snow had completely melted away, and clement weather made life relatively easy, permitting me to sleep in the daytime sun without tending the fire. To allay the loneliness and boredom that takes over during such waiting stints, the search for food becomes the centre of attention. On this trip I tried every trick I knew to obtain food, but the luck of the draw was one duck, period. No fish nor game would fall prey to my lines and traps, no significant edible plants could be unearthed. Nature decides. As far as bugs and worms were concerned, my thousand calorie per day diet was sufficient to eradicate all desire to experiment.

The piece of sheepskin I slept on brings back amusing memories. In an anthropology class, I had convinced the professor that it would be useful for me to learn to sew furs and she agreed to my special project of confectioning a sheepskin parka. Tanned sheepskins were too pricey for me, but a local sheep farm could supply raw sheepskins for next to nothing. I purchased twenty of them over the phone, which I decided I would tan myself. Easily said but not done. The wool was so dirty, disgustingly so, and the other side on which meat and fat remained stuck was no better. I spent two full days scraping those skins over an inclined beam made from scrap lumber, using a large axe file onto which I had taped some handles. Then I soaked them in the boarding house bathtub and washed them with laundry soap and borax.

Meanwhile, I was off to the library to find tanning recipes, and found one using sulfuric acid, easily obtained from an old car battery. While tanning the skins, the acid ate right through the bathtub enamel, leaving me less than popular with the roommates. And the stench from boiling scraps of skin — my first attempt at making hide glue — sure didn’t help.

The recipe then called for washing the skins in gasoline to prevent bugs from attacking them, then to rub them all with hot cornmeal to remove the gasoline odour. The next step was to hang them on the clothesline and beat them for hours to get rid of the cornmeal. The hardest part was scraping them back and forth over an inverted dulled axe head, steadied in a vice, for the entire time they were drying. A procedure that took over thirty hours straight, and I had no choice but to work at it hard, otherwise the leather would become stiff as a board. I ended up with a dozen useful furs, the rest having hardened following my inability to keep up the pace. That was the first time I regretted my ideas of grandeur, and admitted that maybe I had exaggerated in selecting the number of skins for my first attempt at tanning. After some sleep, I had to rub down the good skins with lanolin to keep them soft and then remove the excess lanolin by absorbing it with piles of sawdust. Another trip to the clothesline for a broom-beating session and I thought I was done. Until I started the combing process, which took another several days.

Hanging the sheepskins to dry.

A month later, after three hundred and fifty hours of sewing each stitch with pliers, I had created an incredible parka of Inuit design, complete with hood, which earned me my course grade. The garment was so thick it was way too warm to wear, no matter the weather. After lugging the parka around for a couple of years, I finally cut it down into a vest, which I wore on winter camping trips for a long time to come. One sleeve was converted into the sleeping pad I used on the adventure I just related.