A Sheep

“People, like sheep, tend to follow a leader — occasionally in the right direction.”

— Alexander Chase

The rest of my school year at Thornlea Secondary School was rather uneventful. Except for one day in late March, when I was approached at lunch by a fellow teacher and avid outdoorsman, Frank, with whom I had shared a couple of wilderness canoe trips.

“Hey André, what are you doing after school today?”

“Nothing special, Frank. It’s Monday.”

“Do you think you could come with me to visit a piece of land I’m thinking of buying? It’s about forty minutes northeast of here. We should be back by suppertime. I’d like your advice about the quality of the ecosystem there.”

“Sure, no problem! See you at 3:30.”

As soon as I answered some zealous question posed after the end-of-day bell, I dashed out to the parking lot where Frank was waiting in his fiery red pickup.

“Just a sec, Frank. I’ll just grab the rubber galoshes I keep in the van. There might still be a bit of snow on the ground.”

We headed east from Thornhill, the spring sun blazing through the rear windshield, and after half an hour or so we veered straight north. Soon we hit a country road, then another, and after a few corners and twists and turns, I spotted the realty sign. As we headed out into the woods to check the place out, something felt strange. Then I got it. We were dressed in suits and ties, as per school policy.

Beautiful piece of land. And expansive. The place had nothing in common with the city we just came from. Huge trees, rolling hills; it was a real pleasure to be there, as the sun played hide and seek behind the clouds. I was not aware there were such parcels for sale so near Toronto.

“Frank, this place must cost a fortune!”

“Well it’s not that bad actually. You see, the land for sale isn’t that big, but it borders on the Glen Major Conservation Area we’re in now. That’s what makes it such a good deal and why I’m so excited. What about the environment around here? Anything special?”

Frank pointed out different species of deciduous trees such as oak, ironwood, beech, or sugar maple, and I confirmed his identification and their approximate age of sixty years. As we climbed from a slight valley, a willow attracted my attention. They are rarely found at the top of a hill, since they prefer moist ground; this one must have had long roots. As we continued our exploration, Frank asked me to help him identify the animal tracks we encountered and some wilted plants he wasn’t familiar with. He was quite curious, and as we sat on an overturned hemlock to take a break, he gobbled up my improvised lecture on the ecosystem around us, all the while taking pictures.

I followed Frank’s heels down into the next dip and up the other side, and noticed the well-hidden sun was winning its game of hide and seek. We’d hiked quite a ways through some wonderfully fine woodland. We crossed another insignificant valley, then climbed up a short hill. That’s when I spotted the willow. Two willows on top of a hill on the same day? Hmm.

“Say Frank, do you know where we are?”

“Well, actually, err, not exactly.”

“Why didn’t you tell me? I’ve been following you like a sheep, and we’ve come full circle! We crossed this willow about 45 minutes ago!”

“Are you sure? I thought we were heading back to the truck!”

“Well obviously neither one of us knows where the truck is, and I’m getting hungry, as I’m sure you are. This conservation area can’t be that big. Let’s at least just walk in a straight line, and we’ll eventually come to a road.”

Lost in the woods. For real. I loved it! Then I realized I didn’t have a way to light a fire on me. Ooh, that made me so mad. How could I, of all people, supposed survival expert, be caught in the woods without a means to start fire? Then I recalled that that morning I was heading to a city job in suit and tie. Still, I’ll never again be caught without a butane lighter in my pockets. Never! Never ever! I swear!

“Got any matches Frank?”

“Nope, don’t smoke.”

“Me neither.”

I did have my miniature pocket knife though, and a shoelace, so I briefly considered starting a fire by rubbing sticks. That would take a couple of hours at least, and it would be dark by then. Not a good option. To make matters worse, the clouds were darkening and the barometer was obviously falling, as was the temperature. It would rain that night, no doubt.

No panic. We picked a direction at random and chose three trees that lined up like telephone poles. I stood at the second tree while Frank hiked forward to the third. From there I lined up the second and third tree to spot a fourth one, and guided Frank toward to it. Then we repeated the process, over and over again. That way we were walking in a straight line that would eventually get us out of trouble.

After half an hour of the post-to-post proceedings, I felt uneasy. We’d been walking for two kilometres and there was no sign of civilization yet. Undoubtedly, we had chosen a wrong direction. And as darkness approached it was starting to drizzle. We had no choice but to continue; it was our only chance of drinking tea that night, instead of crouching shivering under some hastily made shelter until morning. Yet as I stumbled along, I scrutinized my surroundings for potential camping spots. Lots of firewood here. Darn! No possibility of fire!

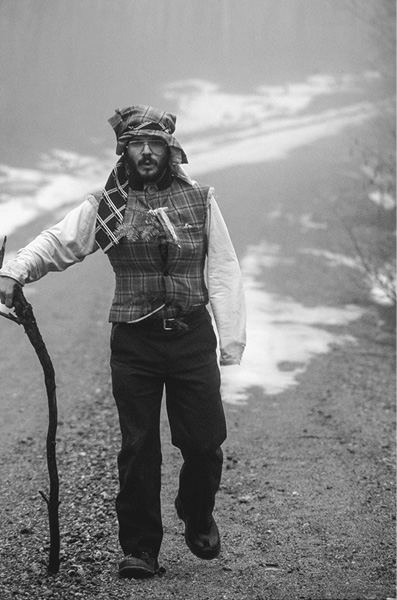

I was getting cold. Without the slightest hesitation, I ripped the sleeves off my suit jacket and used my tie to knot them over my head as a hat. I’d done that before. I don’t care, I always buy my wool Harris Tweed jackets at second hand stores for five bucks, and nobody ever notices the difference. Frank thought I was losing it. I reassured him, explaining the importance of a hat for retaining body heat. As I passed by a fir tree, I grabbed some of the lower branches that had remained dry and stuffed them inside my jacket for added insulation. Frank was scratching his head. He wasn’t sure whether or not he should imitate me.

He didn’t have to. Just four tree-line-ups later, we emerged onto the anticipated road, much to our delight. Our worries weren’t over, for we didn’t have a clue which way we would stumble upon the truck. And there was not a tire mark to be seen. We tossed a coin and went left, finally finding the truck, after many back-and-forths, near midnight. We were starving, wet, cold, and tired. But the next morning found us preaching in front of our respective classes, as if nothing had happened.

I was playing hockey in a local arena. Like any Québécois worthy of his or her name, I love trying to out-manoeuvre my garage league’s goalie. In the dressing room, my fellow players still tease me every time they notice the disposable lighter taped to the belt of my hockey pants. Proof I’ve been respecting my vow. There’s nothing like a close call to drive home Baden Powell’s message to the Scouting movement: “Be prepared!”

My stint as a high school teacher had come to an end. I spent the following summer in Algonquin Park, as I had done for the last five years. Dad had started up a family business managing kitchens for many Ontario summer camps, with the boring name of GB Catering Service, based on his and mom’s initials. GB’s philosophy was to promote camping by providing high-class homemade meals, including daily fresh baked bread and pastries. As eldest son, I held one of the key positions in the company.

My summer jobs had always evolved in kitchens. Starting at the age of fourteen, I had climbed the ladder from pot washer to chef. I served my apprenticeship in one of Toronto airport’s super kitchens. I’ll always remember the first day at work, when the executive chef looked me up and down: “See those eight hundred chickens I just cooked? Bone them out!” The next day I broke forty cases of thirty dozen eggs each into huge omelet mixers, and the day after that I grilled sausages — for twelve hours straight.

Survival dressed in suit and tie.

At twenty years old, when Dad coerced me into being chef at the famous Taylor Statten Camps in Algonquin Park, during its glory days when the dining hall was jam packed with close to five hundred people, at least I was used to bulk cooking. And I was tickled to be in mosquito country, for that meant endless possibilities of practising canoeing, archery, and bushcraft — with the added bonus of enjoying Dr. Tay himself as mentor. Too bad there was so little time left after those gruelling long days slaving over the stove. Secretly, over the next five summers, although I had been promoted from chef to kitchen administrator, I wished I could switch places with one of those fortunate camp counsellors who went off on month-long canoe trips to Quetico or to Kipawa parks. But the expertise I had gained as the lone soul in charge of computerized food planning for the hundreds of canoe trips under GB’s responsibility kept me at Dad’s side.

In early fall, having finally sold my house, including the antique furnishings, I gave all the possessions that wouldn’t fit into my van to friends and family and headed off to the University of Northern Colorado, where I had been accepted into a unique Master’s program in outdoor education. I was enthralled to say the least, so very tickled to have found a curriculum designed specifically for me, perfectly convinced I would learn a great deal more about wilderness survival and open-air life.