Beans

“The most difficult thing is the decision to act, the rest is merely tenacity. The fears are paper tigers. You can do anything you decide to do. You can act to change and control your life; and the procedure, the process is its own reward.”

— Amelia Earhart

“Michel, stop feeding what’s-her-name that cookie! She’ll crap in the van again!”

“Her name is Paulette and she’s hungry, poor thing.”

Paulette was one of three old hens we’d purchased from a farmer, half of our food for the four-day survival experiment we were hurling ourselves toward. The other half consisted of a bag of navy beans. The challenge this time? No container to cook in. And winter camping with only two summer sleeping bags and a pup tent between the three of us, the third Stooge being our friend and former outing club student, Bert. This guy was sharp, the brightest student I had encountered as a teacher. One day for example, I had showed him how to boil an egg in a paper bag and the next he had come back having duplicated the feat in a burdock leaf. Another time I showed him to make toy animals with magician balloons, only to be subsequently delighted by his perfect Adam and Eve interpretations. He was the perfect candidate with which to share our folly.

We cut our anxiety during the drive toward this fifty-fifty confrontation with nature by joking: first about how Michel wouldn’t be able to wring his chicken’s neck after bonding with her, then by recalling Michel’s gag “zonk” gifts he gave everyone at Christmas Eve two days ago — penny-and-paper-clip earrings for our sister for instance — and finally by reminiscing teasingly about Michel’s tire-screeching adventures in his junkyard-parts souped-up 440-magnum Franken-car. Oh yes, we also chuckled when we harked back to the time he carved the spit roast with his chainsaw.

I ended the dull part of the journey by parking the van on a straight stretch of the now familiar Bear Lake Road. Bert and I grabbed our packs and our feathered damsels, and snowshoed off into the woods, breaking trail. Michel immediately followed, with Paulette on a leash. Bert and I were cramped with laughter as he tried to tenderly coax her along.

It was bitingly cold when we reached a promising camping site at the base of a cliff. As planned, Bert and I endeavoured to use deadfall traps baited with the cookie to slay our animals, but the hens and Michel refused to cooperate. We therefore switched our attention to digging the usual fire trench, setting the tent on a thick bed of boughs with the front door opened to let in the blaze’s heat. The el-cheapo sleeping bags sure looked skinny once laid out on the floor of the petite shelter.

Near the end of the day, to Michel’s mostly faked chagrin, the cold sent Paulette to the great chicken-coop beyond. This, plus hunger, incited Bert and me to become poultry executioners. By some strange twist of fate, the two headless birds fluttered directly toward Michel. The big tough guy became the proverbial elephant scared by a mouse and added humour by acting the part. Tears of hilarity thawed our cheeks and relieved somewhat the slaughterhouse atmosphere. As we plucked and cleaned the birds with frozen fingers, we couldn’t help but reflect on how far removed from reality chicken-nugget-eating city-folk have become. And how the fruit of our labour can be so easily purchased, leaving the illusion that we are not responsible for the animal’s demise.

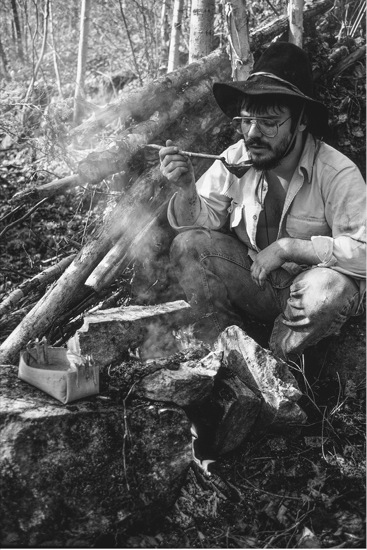

All of that was forgotten once the fake partridge, roasting skewered over the glowing embers, glazed to a golden brown. We found the meal stringy yet delicious, but one lone fowl does not satisfy the appetite of three hungry bushmen. I was the only one who appreciated the desert of giblet shish-kabob. While I was busy licking my fingers and Bert busier still fetching more wood, Michel erected a cross over the buried mound of leftover bones, complete with a charcoaled-inscribed R.I.P. plank. We chuckled, starting to wonder if he was serious.

The bright full moon rose to fade the crisp clear stars, obviously announcing a cold spell that would plummet the temperatures to at least minus thirty degrees. Our faces stung as soon as we distanced ourselves from our blaze. I took the first watch as fire picket, sending my two partners to attempt the clown act of squeezing into the tiny tent. After a couple of hours, Bert exited to replace me, shivering and complaining that the heat did not penetrate sufficiently into the shelter. I replaced him in the sleeping bag, but he was right, it was too cold to sleep for mere mortals. Only Michel snoozed.

But by midnight, even the tough guy joined us and we all squatted intimately near the fire in a semi-futile attempt to warm ourselves. We just existed in a comfortless slouch for a couple of hours, too tired to think straight. Then I reminded myself of my own survival motto: don’t tolerate, activate! I had to activate my brain and body to at least attempt to find a solution. How about moving the fire away from the cliff wall so we could sit between? A lot of work. Maybe we could build a wall behind us to cut the wind? Hard work too. It wouldn’t be easy to fetch building materials in the frigid moonlit darkness. Could we use the tent to erect a vertical wall behind us? I hopped into the tent with the sleeping bag I had draped around my shoulders to examine it. At least in there I could lie down on a soft floor. If only it weren’t so glacial! This gave me an idea.

I coerced Bert to hand over the other sleeping bag, and he reluctantly agreed. Luckily they zipped together. Then I suggested that all three of us take off our parkas and try to squeeze together into the double sleeping bag. It was no sooner said than done, and we managed to toss our coats on top of our matrimonial-style bag. With no one left to tend the fire, the tent door was zipped shut, leaving just a small opening for ventilation. The strategy worked; we generated enough body heat to sleep.

It was past two o’clock the next day when our next short order of roast chicken arrived, without French fries. Nor beans. The survival book I recently read made it sound easy to boil water in a birchbark vessel; apparently the water keeps the bark from burning. I was motivated by hunger to work up a side dish of beans.

I’d made lots of birchbark containers before, so I thought it would be a piece of cake. I headed for a suitable Betula papyrifera, only to find the bark frozen solid and impossible to remove, except for the wispy thin and fragile dangling layers. So I kept searching until I found a leaning birch tree, under which Bert helped me start a fire. After a while the bark thawed enough so I could peel a suitable piece. To fold the corners of the rectangular container I wanted to create, origami style, I needed to soak the bark in boiling water — duh, that’s the objective — so Bert suggested I alternate dipping it in snow and then holding it by the fire. I pinched the creased corners with split maple twigs, making sure to select segments just below a knot to prevent ending up with two pieces. A pot was born, all white inside.

Bert had been making water by melting snow in a t-shirt bag suspended near the fire. The water dripped into the plastic bag in which the navy beans were sold; we had dumped them into a rucksack pocket as part of the let’s-maximize-our-resources camping shuffle. I poured the water into my birchbark vessel, satisfied it wouldn’t leak. With gloved hands, I deposited it gently but quickly onto the bed of glowing coals, hopeful. Indeed, it was amazing that the bark stayed intact. Below water level, that was. I watched helplessly as the bark above the waterline flamed up, leaving the homemade clothespins hanging until the bark collapsed, with the fire hissing at me as if to shame my ineptitude.

I returned to the leaning tree, where I repeated the process and managed a second sheet of bark. Then I used four flat rock flakes — which had caked off the boulder the fire was leaning against — to install an elevated platform with a square central hole so that the flame would only caress the pot’s bottom. I transferred embers under the platform and added kindling wood. For a few minutes my strategy seemed to work, but soon the flames licking the pot’s underside poked through the tiny cracks between it and the rocks of the platform, and the second container suffered the same fate as the first.

I searched further in the forest until I found another leaning birch tree underneath which to build yet another fire on a raft of rotten logs placed on the snow. By the end of day, I had obtained three decent sheets of bark, although not as thick as I would like. Failing daylight prevented me from completing my project. We hit our crowded bed hungry.

After a lousy night’s sleep, I was up bright and early to face the excruciating cold. I barely had time to strike the match before becoming the victim of frostbite. How glad I was to have prepared tons of birchbark shreds and kindling the night before! Soon a two-metre-diameter warm haven let us melt our frosty whiskers. As my partners attempted to thaw the remaining hen enough to skewer pieces onto a stick, I was back on the cook-the-beans project. I constructed another pot and set it on the platform. With thawed mud scooped out from near the fire pit, I carefully plastered all cracks around the container. Finally, the water started steaming. But the heat softened the too-thin bark, and the container wilted, spilling half the liquid. By then I was more than a bit exasperated by popular survival literature, wondering if the authors had ever abandoned the comfort of their plush La-Z-Boys or Barcaloungers to try the skills they professed.

The partly extinguished fire permitted me to add a couple of fist-sized rocks on each side of the pot and solidify the set-up with additional mud. At last I gladly basked in Michel’s and Bert’s congratulations at the sight of the feeble litre of boiling water. I tossed in a couple of handfuls of beans. As a chef, I knew that these take a great many hours to cook in liquid thickened with other ingredients, but will cook in as little as a couple of hours if dropped into boiling water only. In this case the process was tedious, as I repeatedly had to add finger-sized firewood under the platform, and occasionally replenish the evaporating water from another container Bert had fashioned. Four hours later, we enjoyed a tiny cup each of flavourless effort. At least it was food, and the setup remained functional for another batch, and another after that. But after having chased firewood all day, we were still starving as we hit the sack, entertained that night by a strange gastrointestinal concert.

On the fourth morning we couldn’t stand the masochism anymore, and I was certainly not up to the task of repeating the complex bean routine. My energetic “Let’s get out of here!” met with considerable enthusiasm. In no time we had cleaned up, leaving behind no trace but a few scattered blackened rocks that would be covered by forest litter within a year or two.

Boiling water in a birchbark container. Much easier in summer!

Panting from the brisk walk in a cloud of steamy breath, I’ve rarely been happier to pat my old van. My partners quickly tossed in their packs on top of mine as I turned the key in the ignition. Tic. Again. Tic. Tic. Dead battery. Tic. Very dead. Crap!

That was the day I learned to leave survival food and gear in my vehicle at all times. Road #12 was at least a dozen kilometre walk, and once there we didn’t know how lucky we would be at hitchhiking even if we did encounter traffic. The alternative of staying put was no better: we would no doubt freeze before rescue. I decided to apply the STOP principle and start a fire on the road in front of the truck to warm us up while we would think this one through. After a moment of mindless staring into the roaring flames, it occurred to me that if we waited until the fire fell to a bed of coals we could then push the van over the embers to warm the oil pan and battery; or even scrap our aluminum toboggan or a hub cap for the purpose of sliding embers underneath the motor. This of course teetered on dangerous to me, but were the only options. An hour and a half later, just as we were about to realize our plan, it occurred to me to first try the key, since the bumper was warm. The motor roared.

As we stopped for grub at Dorset village’s only and lonely gas station open for business on this holiday evening, we benefited from another valuable lesson: cola and chips don’t qualify as real food — we would have preferred more chewy chicken and bland beans!