Retro-Propulsion

“Study the past if you would define the future.”

—Confucius

Jim the pilot was inventing eternity as he filled the gasoline tank with jerry cans that he had transported as baggage. The regional newspaper was lying on the back seat of the aircraft. We had made the headlines, complete with a full-page photo of us with arms victoriously outstretched. I devoured the words until prevented from doing so by the whirring of propellers. We asked Jim if he could circle above our camp one last time to impregnate ourselves with the territory in which we had survived for thirty-one days. What a sweet impression.

I immediately enquired of Jim whether he had any matches. He handed over a partly used booklet of paper saviours, which I cautiously stowed into my pocket. Now we could crash, we would survive. Stopping briefly at the heliport of the Chicoutimi hospital, we threw ourselves in the arms of our friend Jean-Claude. He had arranged for a doctor to briefly examine us prior to hopping over to the parking lot of the city mall. I had expected a hundred people; there were thousands, all waving at us.

When we landed in the crowd I was looking for a single pair of eyes, those of my mother. As soon as I located them, I pointed a finger and rushed toward her. For a brief moment, the multitude disappeared. After I had also embraced my father and my brother Réal, the swarm was suddenly back in focus.

I had sworn to deal with each individual as a special person, and so with utmost sincerity I saluted each with care. Many close friends had come to greet me. I was moved. Women, especially, each more beautiful than the other, greatly impressed me with the bright colours of their now seemingly foreign costumes and the strange scent of their perfumes. One spectator surprised me with her remark:

“Mr. Bourbeau, what you two have done is so fantastic, so extraordinary, it’s more important than the coming of the pope next week!”

Another individual was so insistent that I give him a piece of my shirttail that I offered him my sleeve toque as a gift. He was jubilant.

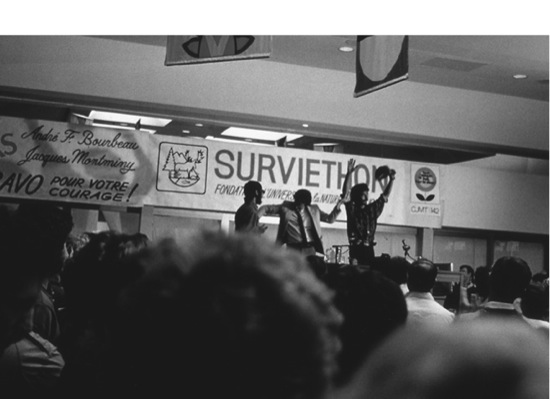

Jean-Claude was carving a path in front of us to inside the mall where a press conference was to be held. We eventually climbed the podium, and Jean-Claude lifted our arms as a referee does with winners in the ring. Speechless, Jacques and I bear-hugged. Adrenaline-driven and without thinking, I grabbed my buddy by the waist and lifted him straight up over my head.

The post-Survivathon press conference.

Chairs were provided for the two of us, as well as for the president of the foundation for Nature’s University and the rector of the University of Quebec. The latter was elegantly dressed in full three-piece suit and tie. What a contrast to our rags!

After the dignitary speeches, our responses to the journalist’s questions had the crowd roaring with laughter, like when they asked what we ate and I related the burbot incident with an exaggerated imitation of the sucker’s ugly mouth. I appreciated that people were so attentive we could have heard a bug fly. Gradually the crowd dispersed and left us with our friends. I excused myself a moment to go to the bathroom. A mirror! What a shock to see my thinned face wearing those spectacles. Soap! I remember watching the muddy water spiralling down the drain.

It was nearly four o’clock before Jean-Claude drove us over to the university’s physiology laboratory. My colleagues measured our anthropometric data, took blood samples, and evaluated our fitness levels. Not having eaten a morsel since the previous day, I couldn’t believe I was still able to execute forty-eight sit-ups in a minute. The data revealed that I had lost 9.4 kg and Jacques 13.6 kg. Only our electrolytes were below norm from the lack of salt. Aerobic capacity had taken a drop due to our intense fatigue. After a few days both measures had returned to normal.

Finally we were each offered a hotel room where we enjoyed the long-awaited shower. What a thrill. Then I absolutely devoured four bowls of mom’s homemade chicken soup, with dried fruits, nuts, and a sandwich. All this I considered appetizers before our subsequent smorgasbord at the restaurant. I was as amazed as everyone else by my appetite. I started with another soup, a veal steak with rice, and two orders of fondue. Then I ordered a fried chicken breast with a portion of mushrooms in garlic butter. After two raids at the salad bar I was finally ready for dessert. I polished off a slice of apple pie, a butter tart, as well as a piece of pecan pie. I was stuffed, but the management brought out a specially prepared chocolate cake, on which they had erected a primitive camp made of coloured fondant. I honoured the chef by eating two pieces, which was hardly a chore. Mom couldn’t believe her eyes. She never found out that I had gotten up in the middle of the night and drove to town to fetch myself a giant poutine.

The next day I woke early and headed to the restaurant again. I couldn’t wait to eat! Eggs, bacon, sausages, toast, pancakes, jam — I ate everything in sight, even the remains in the plates of other customers sitting near me. I could not tolerate the waste of food.

After three days of such a regime, I had gained back 6.8 of the 9.4 kilos lost during the month! And I was never ill; perhaps the giant fish and more abundant berries of the last week had prepared my stomach for the feast.

This phenomenon of extravagance also occurred at the intellectual level. Thirsty for action, I plunged into life with a passion. That autumn I presented the Survivathon research results in scientific circles, gave in excess of thirty public lectures throughout Quebec and Ontario, appeared in over twenty television programs, produced a slide show, worked on a video, began to write a book, revised my computer software for trip food, and developed a prototype survival kit for the Boy Scouts, all the while teaching three courses at the university. I couldn’t understand how students could complain about the small amount of homework I asked of them.

It took until spring before I calmed down.

Meanwhile, behind my back, Jean-Claude had submitted the Survivathon adventure to the review committee of the Guinness Book of World Records, who accepted to log the trip as the longest ever voluntary wilderness survival experiment. That, plus the book I wrote in French relating the day-by-day details of the Surviethon turned me into a public figure in Quebec, whether I liked it or not. At first I enjoyed the spotlight, but I soon tired of it. After a hundred re-iterations, I started cringing when approached or introduced as “The guy that spent a month in the bush. You know, the guy with the funny wooden glasses.” Or even worse, “You know, the guy that ate squirrels.” Apart from those reminders, though, the Survivathon was behind me. I was relieved when the years erased memory of me so that I could walk incognito again.

Thirsty for a new project and using “Semester at Sea” as an example, I convinced the university’s administration to let me offer its first ever multiple-course expedition. It seemed to me that the curricula of outdoor leadership, research seminar, pedagogy, and philosophy of outdoor education, and a special project in physical education could all be combined with advantage. A group of dedicated students accepted the challenge. We dubbed the alternative education endeavour “Changing Gears ’86,” an appropriate name for a cycling trip across Colorado’s Rocky Mountains and over to California and the Pacific Ocean. After a year of preparations and fundraising, we clambered aboard the minibus on our way west, bikes and panniers in the towed trailer, and drove across eastern America.

Part of the course work included planned visits, and we stopped to tour the manufacturers of outdoor equipment such as North Face and Marmot Mountain Works, received lectures from the leaders of the outdoor programs in multiple universities, participated in summer camp programs, toured a nuclear power plant, and so on. The research seminar tested bike equipment and food packing systems. We carried a rolling library of books on outdoor philosophy, with daily readings. By necessity, one student learned to cut hair. Intensive English immersion was a bonus. Outdoor education pioneer L.B. Sharp would have been proud.

The trip rolled along on ball bearings, both in the real and figurative sense. Until one night. Sleeping like a log in my tent after a hundred-plus kilometre day, ear muffs on, in a standard private campground, I was startled awake by the blaring sound of loudspeakers right next to me and an ultra-bright spotlight shining on my tent.

“Are you the leader of this group?” yelled someone through the microphone. I stuck my head through the tent door and stared down a revolver barrel aimed straight at my squinting face.

“Yes I am, what in the world is going on?” I nervously answered with my hands up, kneeling in my underwear.

And the uniformed cop, backed up by three others replied: “Your boys were yelling murder threats to the camping neighbours!”

Turns out my team had been partying with alcohol and I hadn’t heard the slightest sound. And now of course, they were all dead asleep and I couldn’t raise a soul to answer my questions, nor the cop’s. Since they were partying in French, I suppose the worried neighbours had imagined the worst. After plenty of apologetic explanations, I got off with a warning.

The next morning I faced a very timid group of students who stammered regrets at having bypassed the rules they themselves had written up and formally signed, stating that they would restrain alcohol consumption to below legal driving limits. I had learned a good lesson as outdoor leader: you can’t override human nature. From then on, all long trips near stores would include supervised party nights with paid security guards.

We had many minor adventures on the trip, like a flipped raft in rapids and a scratched helmet following a gear-failure-caused accident. But the highlight was certainly climbing for hours up and over snowy 3,448 metre Monarch’s Pass, then sliding down the other side through mushy sleet.

Project “Changing Gears ’86.”

Once back in Chicoutimi, and the post trip tra-la-la taken care of, I resumed my work being a typical university professor for a while, which was comprised of three main tasks: teaching, research, and community services. So I wrote and compiled course notes, organized a scientific colloquium, submitted memoirs to protect wild rivers to the Bureau d’Audiences Publiques sur l’Environnement, contributed to Expo-Nature, wrote a chapter on survival for a collective book, prepared and submitted a few articles, and so on. Tons of boring stuff.

Then one day I received news through internal university mail that grants were being offered to researchers for projects related to the 150th anniversary of the Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean Region, two years hence. What better way to celebrate such an event than to relive 1838? Why not show the population of the Domaine-du-Roy what living and travelling was like when twenty-one individuals founded La Société des Vingt-et-un and came to colonize the fjord?

After some lobbying, I obtained the funds to organize a historical re-enactment expedition that would cross the entire region, stopping in every town and village (over thirty) to perform demonstrations of our ancestor’s way of life. After spending days at the National Archives, I unearthed the original journal of Joseph-Louis Normandin, the first surveyor of the region in 1732. Normandin had travelled from the Metabetchouan fur trade post on Lac-St-Jean, up the tumultuous Ashuapmushuan and Chigoubiche Rivers, along the Licorne River, across a chain of lakes, and then up the river that now bears his name to end in the Nicabau fur-trade post. I had found my itinerary. As authentic “coureurs des bois,” we would follow Normandin’s route to Nicabau, pick up some bales of fur there, and lug them back along the same route and onward downstream on the Belle and Aulnaie Rivers, across the chain of lakes to the Chicoutimi River and down the Saguenay River to Tadoussac on the shores of the majestic St. Lawrence River. Nice.

Today, of course, organizing such an expedition would be simple enough. Since the advent of Internet, a great number of online stores have popped up where one can buy accurate reproductions of each and every piece of gear needed. But back in 1988, we had no choice but to make our own. Just trying to figure out what gear was available in that time period and what it looked like was a major undertaking. And since this was a research project, I wanted everything to be scientifically accurate. No compromises. I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

“How much for those cow guts?”

“You can take as many as you want. No charge.”

“Wow, thanks!”

My long time buddy James Déraps and I grabbed a dozen soggy bladders and a few dirty intestines and exited the murderous scene of the slaughterhouse. Back at the indoor locale of the university’s “outdoor lab,” Mike Martineau and Marcel Savoie, two former students turned good friends, were busy hand sewing their smoked rawhide moccasins with a homemade awl. James and I washed out the slimy guts and hung them to dry. We figured these would come in handy to keep our stuff dry.

“Merde, those things stink!”

Mike was right, so we opened the window and hung them outside, dangling from a rope draped over the sill and tied to a central heating radiator. I wondered what the passers-by would think. Who cares! I finished cleaning the sink and threw the remaining gut scraps into the aquarium, where Tourtière, my loyal snapping turtle, resided.

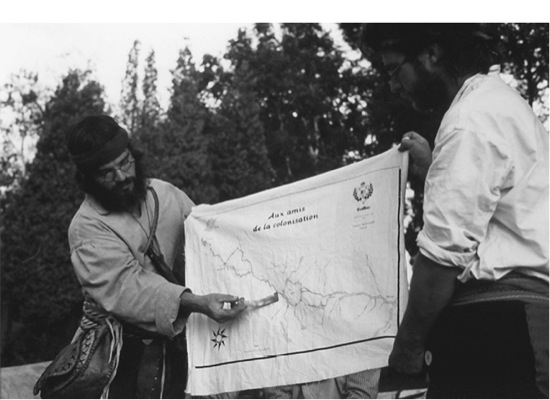

I glanced around the room, satisfied with the results of our last nine months of work. We’d forged our crooked knives and needles from old files, retraced Normandin’s original map on canvas with India ink, sculpted a checkerboard onto one of the many paddles we’d crafted, found a copper pot and dishes, and bought a Brown Bess flintlock musket. Since I couldn’t buy spare flints for the gun, I went to meet a flint-knapping pro in the States who showed me how to make them. In fact, most of the information we’d gathered had been through word of mouth contacts, and I’d been enjoying getting away from Chicoutimi to visit the people I was referred to.

We’d also hand sewn countless ditty bags, gathered spruce gum and extra bark as a canoe repair kit, waterproofed cotton tarps by painting them with raw linseed oil mixed with turpentine and iron oxide, found an elderly lady who showed us how to make bars of soap made from fat and ashes, bought some intricately decorated birchbark vessels from a Native artist, and scrounged up pure wool blankets from the back shelves of various flea markets. On the central table were traditional wool socks, containers of natural bug dope concocted from camphor, citronella, and cedar oils, a period comb, four tumplines, two types of gun powder, bear grease, a fishing net, noggins, a brass compass, coils of rope, a leather-bound journal, ink, vermillion powder, an axe, and a crude pig-bristle toothbrush of my own undertaking. Oh, and a small wooden barrel to carry the rum, of course.

Thanks to my research assistant and friend Trudy Morphet, also a wonderfully talented artist and craftsperson, the hand sewing of our undergarments, felt pants, and cotton shirts was coming along fine. I also felt deeply indebted to her husband Greg Cowan, who crossed Canada as a voyageur back in 1967 and who was helping us build gear. Greg happens to be the most incredible handyman I know, one of his accomplishments being the construction, with ancestral tools, of a fully outfitted historic wooden sailboat, complete with steam engine. I was hoping he would accept sailing our fur bales and us the hundred and twenty kilometres from Chicoutimi to Tadoussac at the end of our trip. He was visiting and in no time had helped me transform two raw bullhorns into fine-looking and functional gunpowder horns.

Most importantly, I’d convinced my friend and mentor Kirk Wipper of the Kanawa Canoe Museum to lend me two of his precious birchbark canoes. Although he assured me that those two particular canoes did not have historical significance, I was well aware that he would not let anyone else use them for a trip. He even told me the canoes would be worth more after they’ve been on a trip with me! Nice guy.

But there was still a lot to be done. My traditional fletched sash belt was in the process of being woven by hand, knot by knot, by Mr. Rondeau of the Association des artisans de ceintures fléchées. He was charging me eight hundred dollars for an eight hundred hour job. A passionate artisan! I still hadn’t solved my eyeglasses problem and we hadn’t even started packing food.

I’d been spending a lot of time with the region’s historians gaining insight on the way of life of the coureurs des bois. But to understand their concrete day-to-day life, it was my Native mentors Jimmy Bussom and Gérard Siméon I turned to. Their knowledge base astounded me; at my first contact with them, I became aware of my beginner status. Humbly I soaked up their teachings. Through them I met René Robertson, the Native fur dealer, who set me up with a large batch of sub-category fox, wolf, and beaver skins. The historic fur-trading post and tourist attraction in Metabetchouan would furnish me some fake bales of pelts for the return trip.

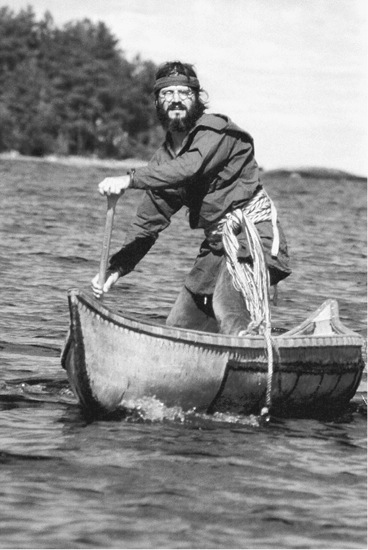

After having spent over a year of spare moments reading every historic journal I could lay my eyes on, I surprised myself by feeling transformed, perhaps like an Elvis impersonator who starts believing he actually is the King. As I read Robert Ballantyne’s account of his service with the Hudson’s Bay Company in the 1840s, his description of himself in the mirror after a trip served as model for my own clothes: a blue canvas capote, brown corduroy pants, a headband, a sash belt, and Indian moccasins. To this outfit I had to add eyeglasses. In those days, you looked through a series of demonstration lenses at the trading post to pick out the ones that corrected your eyesight best, ordered them from England, and received them a year later. The Saguenay Museum happened to own a pair of original frames from that time period. I copied them exactly by welding pieces of metal tubing cut lengthwise into circles. The side bands didn’t reach behind the ears, they ended in rings near the temples instead. To those I tied a lace of eel skin, just like in the old days.

Three months before the trip I hired two bright gals as a promotion team, Jeannette and Jacynthe. They planned all of our demonstration stops and handled the logistics and the media while the expedition was in progress. During a brainstorm, we decided to call the project Retro-Propulsion, the French term for back paddling. Since the stroke was so useful to descend rapids safely, and has the back/forward double meaning, we found it was particularly appropriate for a sojourn whose aim it was to paddle in the past to better foresee the future. A way of introducing the save-the-rivers message.

Since all was going according to plan, I also wrote up a full description of the project and sent it off to National Geographic and a dozen other similar organizations in the hope that one of them would be interested in filming the story.

One month before departure I contacted one last time the Masteuiash Reserve to try to convince the Native people to join me for at least part of the trip. In a fit of extravagance, I suggested they could travel with us on Lac-St-Jean in a canot du nord. They said it was possible. Getting Native people involved seemed like a wonderful opportunity to share with them, so I called up my friend Kirk at the canoe museum and begged him to lend me a large birchbark vessel, which I would take care of like my own eyeballs. He agreed.

The resuscitated Robert Ballantyne.

The next weekend I hopped in my Volvo with James and we drove the thousand-kilometre trip to Ontario to fetch the canoe. Professor Kirk could not meet us at the museum, so he told me where the boat was and authorized the security guard to give me access. When we arrived, James and I were stunned at the size of the beautiful craft. There was no way to load the thirty-foot canoe onto the car, unless … We headed off to the lumberyard and bought a dozen two-by-fours and a hammer with some nails to build a huge rack. An eternity later we were finally off to Chicoutimi, but couldn’t drive more than seventy kilometres per hour. For eighteen long hours, every single vehicle on our route stared at us in disbelief. We decided to deliver our unusual car-top load directly to the shores of Lac St-Jean, an extra three-hour drive.

We arrived home by sunrise on Monday morning, and I gleefully hopped into bed to catch some sleep before my afternoon class. But the phone shook me awake at 10:15. It was Kirk. We had grabbed the wrong canoe! The one we had wouldn’t float; it was built for museum display only. Oh well. It would make for good photo shoots, I guess.

The final preparations went well as we packed up our gear and food such as peas, barley, homemade hardtack biscuits, whole-wheat flour, and dried prunes. Oh yes, and one whole smoked beaver that my Native friends had graciously provided, warning us to keep smoking it as we went.

Then Jeannette popped in with great news. KEG Productions/Ellis Enterprises from Ontario had agreed to send a film crew to spend ten days shadowing us in the wildest part of our journey. And not just any film crew. Ken Buck would be behind the camera, the very guy who filmed the legendary Bill Mason in his red canoe. Wow!

I phoned the director Ralph Ellis and we agreed that to maintain scientific integrity we would have no interaction whatsoever with the film crew, who would discreetly follow us from a distance.

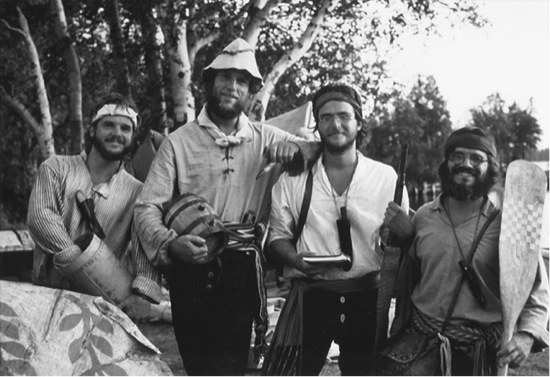

At long last it was D-Day. The four of us proudly posed besides the huge north canoe, which would only serve on our return leg during the promotion/demonstration segment of the trip. Then we waded into the water and loaded up our fragile flotilla. Mike was in the bow of the fourteen-foot canoe I was sterning, whereas James sat in front of Marcel in the sixteen footer.

An unusual car-top load.

The Retro-Propulsion crew posing, just prior to departure.

The inland sea is pretty rough for such small and overloaded craft, and we barely progressed one kilometre before we had to pause to reconsider. Our canoe was shipping water over the side, and Marcel’s and James’s canoe had already sprung a leak. We stopped for repairs on a private beach and had to convince the owner we were not weirdoes. Near suppertime the winds abated and we pushed onward. It was a particularly scorching July day, and soon thirst drove us to pull over again, for the lake was too polluted to drink. We used the flintlock musket frizzen and gunpowder to get a lamp wick smouldering, and then blew the cotton into flame using shredded cedar bark kept dry in a cow bladder. We set a pot of water to boil and as soon as it cooled to lukewarm, gulped the contents.

For three days we had to repeat this process bi-hourly, as we paddled past the towns of Roberval and St-Félicien and started up the Ashuapmushuan River. What a relief it was to leave the Donahue pulp mill behind us, and finally attain clean water.

Clean water, but disgusting food. At lunch we discovered that the body cavity of our smoked beaver was being devoured by hundreds of maggots. To think that last night, in the darkness, we were feeding off of this same carcass. Oops! We should have listened to our Montagnais friends.

One of the canoes was giving us endless trouble. In desperation I removed half the ribs and cedar planks and slapped pitch on it from the inside, covering the leaky spot with a tarred rag.

We were following Normandin’s daily journal entries, and we were already a couple of days behind his 1732 schedule. Portaging became unbearable because we were carrying too much junk. So when Jeannette and Jacynthe came to meet us at Chutes à l’Ours to check on our progress for a media report we unloaded just about everything except food, one pot and noggins, our tarp, one blanket, and an extra shirt each. We entered the wild Ashuapmushuan Reserve, and wouldn’t have contact until we reached Chaudière Falls, two days travel according to Normandin’s notes. Ken Buck and his canoeing partner joined us and were following behind, tiny dots in a Grumman aluminum canoe. We soon forgot they were there.

The mosquitoes must have known exactly where the boundary of the reserve lay, for as soon as we entered our first wilderness portage they proved without a shadow of a doubt that our ancestral bug dope was useless. That night I draped some cheesecloth over four sticks poked into the ground to create a bug net over my face. But in the morning as I woke to a smiling camera peering down at me, I noticed that the enclosure was jam-packed with the needle-nosed critters. In the wilderness, it was easier to make friends with our brother the wolf than with our cousin the skeeter. These distant relatives were having a happy party this morning at my expense, with shelter, warmth, and an all-you-can-eat skin buffet.

Ken was discreet. No sooner had he filmed his shot, he was gone. We noticed him again later as he crept up to capture images of us waiting out a downpour under our tarp. He didn’t say a word.

During the summer, the Ashuapmushuan flows at about three hundred cubic metres per second, and the current rushing against us slowed us to a crawl. For four full days we paddled hard from dawn until dusk, unless we were portaging, lining, or dragging the canoes, sometimes with water up to our waists. Late afternoon of the fifth day we reached the base of the Epinette Blanche Rapids, a kilometre-long R-3 without a portage trail. We attempted to go up the right bank. Wrong choice. After a couple of hours of dragging the canoes against the forceful flood, we came to a tumultuous rolling wave at the base of a sheer cliff, which decisively barred our way. We would have to return downstream and ferry over to the other bank to try again.

But the day was way late and we were way beat. Trying to ride the waves downstream seemed suicidal. Out of options, a barely climbable narrow ravine was the only way to leave the river’s edge. In semi-darkness, the weary voyageurs used ropes to lug their gear and their canoes up the crack and tie them to trees. We each found a spot to sleep by wedging ourselves between a tree and the rock face. Never again would I complain of a sloping campsite! And in comparison to our cold and unbreakable biscuits, any warm supper would be welcome.

To make matters worse, poor Mike was suffering from a serious case of poison ivy, which had spread from his legs to his upper body. Unfortunately there was no way to relieve him until we finally arrived at Chaudière Falls two days later. Eight days! It took us eight full days to cover what Normandin had managed in two. We bowed our heads in respect.

The daylong break at the falls was welcome, as we admired the giant rock cauldrons carved out over centuries by water-spun pebbles. We also appreciated the moose steaks our land team surprised us with. It sure beat the sea gulls we added to our barley the day before.

The next leg of the journey involved ascending the Chigoubiche River, starting with a steep portage over a gushing tall waterfall. Lovely. Judging by the overgrown and dense forest on both sides, it seemed as if the route had not been used since the fur-trade era. We grabbed the axe and took turns chopping a trail until we reached calm water. Since the Chigoubiche is profiled like a staircase, it was easier going than the Ashuap. Soon we reached Chigoubiche Lake and portaged two kilometres through bush over to the Licorne River, which was nothing but a meandering creek. When we reached Lake Ashuapmushuan, we attempted fishing with our net across its mouth, without success. Since this practice was illegal without the special permit we had obtained, we of course had no idea how to go about this. And with not enough time to learn by trial and error. Another question for my Native mentors.

Footwear was becoming problematic. We were not even halfway through the trip and our moccasins were pierced right through — not on the heels and toes, as expected, but rather in the centre of the soles because of the round cobbles we kept hopping on. The leather stretched way out of shape while wading, and at night the mocs shrivelled up to the point where we could hardly get them on in the morning.

One of my favourite pieces of gear was the greased-leather dry bag I sewed from a dog skin the local taxidermist had offered me. Even when submerged, my blanket and shirt stayed bone dry. I loved my sash belt too. It acted like a weightlifter’s belt when portaging, made a suitable emergency tumpline, and doubled as a comfortable pillow. More importantly, because it was wide and made of wool, it acted as a warm layer when draped behind the neck, criss-crossed over the torso, and tied around the waist.

That night we were camping on a large rock outcropping. I ogled the oily water, wishing I could jump in to evade the heat wave. But in the calm before the storm, mosquitoes were particularly fierce; in fact, they were more ferocious than a junkyard dog. Tired out by the portage bushwhack, we decided to skip cooking supper. Starved, I dumped out a lumpy ditty bag full of walnuts onto the rock. Oops, that was the lumpy ditty bag full of spruce gum. I half-heartedly fixed my frustrating mistake, repacking just the biggest hunks of resin.

We decided to build a triangle of three smoky fires to get rid of the beasties, but they zoomed in on us anyway. It was hell. We lay down to avoid suffocating, with our blankets over our heads to prevent bites. The heat was unbearable. Sleep was hard to come by, but accumulated fatigue eventually forced my eyes shut.

I must have been dreaming. As if tarred and feathered, I was hot, sweaty, and gooey. I was rolling around in warm viscous glue, my hair welded into lumps. I pinched myself. I was awake. This was real! What the? Jesus! The heat from the fires had melted the spruce gum I had left laying on the rock, and it had flowed down onto me. The icky paste was plastered all over my hands, face, hair, clothing, and blanket. Yech!

Three days later we had reached the height of land and our destination at Lake Nicabau where our loads of fur bales were waiting. At long last we started back and could now enjoy flowing with the current. The Normandin River rapids gave us a thrilling ride, a wonderful reward for the upstream efforts. Then we entered the headwaters of the Ashuapmushuan and were whisked along. However, since we didn’t have life jackets we portaged many rapids that we would normally have shot through.

During a long straight stretch of this fun part of our journey, I unlocked that spiritual mindset whose key is repetitive paddling. I couldn’t help but be amazed at how I was floating on nature, both literally and figuratively. Below my knees were cedar boards and birchbark that simultaneously grow and breathe around me. The roots and gum holding the canoe together exist right there along the shore. My linen sleeves had been woven from plants I have seen in a garden, and I have witnessed the entire transformation process. Same with my moose-hide moccasins. What an awe-inspiring moment!

And as I delightfully watched the other canoe drawing pretty ripples on the dark blue sheet, I was transported into an era of simplicity and direct contact with our priceless environment. Clean, fresh air, crystal-clear pure water, good friends. I marvelled.

As we zipped along, I came to view the wild Ashuapmushuan’s rapids as diamonds on Princess Nature’s tiara, with the Chaudière Falls as its crowning jewel. Each tree applauded her passage, and we, lucky part of the parade, were enamoured with her beauty.

In that context, who cared if our food stores were down to flour, onions, and lard? Content with our onion rings after twenty-eight days of mostly bliss, we were back at Lac St-Jean. We all admitted to knee weakness when we first encountered the bikini-clad demoiselles who had come to meet us at our first historic talk on the beach. So much for historical accuracy! Musket shooting demonstrations and fire-by-friction or with flint-and-steel felt weird amidst the audience of beer-guzzling and Speedo-wearing city dwellers.

We traversed the big lake in paddling sprees from demo stop to demo stop. Only the passage straight across Chambord Bay made us wish we had gone around. The canoe was acting up again, and leaking as fast as James could bail. Close call.

James and I during a retro demonstration.

The only other noteworthy event on the way to Chicoutimi was paddling the historic Aulnaie River through the village of Hébertville, as it was quite obvious where its sewage ended up. That sure flamed our talk of the day.

When we arrived in the city of Chicoutimi a few days later, a strange feeling overwhelmed us as we portaged around the dam on asphalt, dressed retro as we were. Especially when we had to wait, canoe on shoulders, for the traffic lights to turn green. Anchored next to the downtown Chicoutimi bridge, Greg awaited us on his charming sailboat Jamestown. He beckoned us to hurry; tide was going out. We tossed our gear and the fur bales on board, and sailed off toward the east, boat tilted to the max.

The Saguenay Fjord impressed with its majestic cliffs and deep, dark waters. We spent three days in another century’s heaven, cruising with full sails on a broad reach all the way to Tadoussac. Perhaps there was a lesson here. Hmm, wilderness without hardships. Interesting!

The sailboat Jamestown.