The Opera Singer

“If you keep your emotions locked in a box, then when you want to open it one day you’ll find that they’re gone.”

— James Thurber

After the memorable fortieth birthday party where my snow-filled canoe served as a beer cooler, wilderness adventures came to be few and far between. Not that there weren’t many terrific outdoor trips. It’s just that I was applying the risk management principles I was professing to prevent the occurrence of nasty events. But I managed to find my thrills in other ways.

Certainly work was fulfilling, as I pursued former interests with renewed vigour. With a colleague from the anthropology department, I founded the University of Quebec’s first research laboratory in primitive technology. The advent of Internet permitted me to create the Primitive-Skills-Group so I could share findings with like-minded folk. I also enjoyed spontaneous experimentation, such as figuring out how Pierre St-Germain of the Franklin Expedition had managed to build a shrub-framed canoe out of a tent to cross the Coppermine River, exploring fire-by-friction in the physics lab using thermo-couples and infrared cameras, or inventing better emergency snowshoes when limited to using only shoelaces.

Similarly, I pursued my tripping food research, spending an entire sabbatical leave on this subject. I improved my trip food planning software until it was ready for marketing. But as everyone knows, I’m no good at that. So I made it available for free and it is now used all over Quebec.

On the environmental side, I became a Leave No Trace Canada master educator instructor to influence the movement from the inside. I was mostly successful at this, having helped rewrite the Canadian reference booklet and training those new instructors that would go on to offer the master educator courses in Quebec.

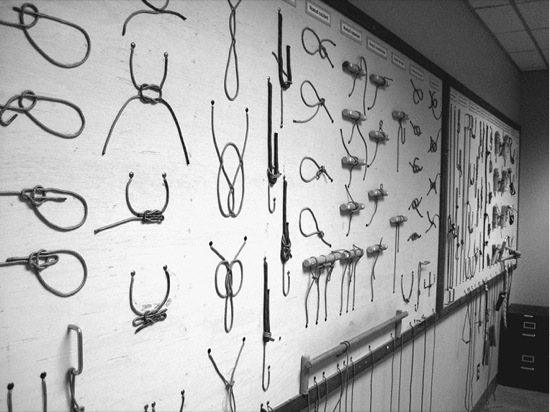

But certainly the highlight of my career was founding the first ever Bachelor’s Degree in Outdoor Adventure and Tourism with my long-time buddy and colleague Mario Bilodeau. Together, we designed a unique program with two intensive sessions taught almost entirely outdoors, whose main purpose was to form leaders for Quebec’s expanding backcountry tourism industry. Like dedicated parents, we took care of our baby by creating all sorts of stimuli. For example, to teach security with tools we had vans drop loads of full-length logs on campus so students could practise, which also permitted them to earn money once they had sawn and chopped them into firewood. We invited the rector and other dignitaries to thematic banquets students organized in the outdoor classroom we had built in the woods behind the campus. We designed major first-aid and rescue simulations that felt real. We challenged them to beat the existing record for the knot board I had designed.

I directed the program for the first six years, fighting to obtain funds, technical staff, and dedicated spaces for gear. I also founded the Outdoor Research and Expertise Laboratory (LERPA) as a support structure. That took a lot of steam out of my locomotive. But the results were worthwhile, as we watched our offspring inundate Quebec with innovative ideas.

Upon conception, based on the success of the Changing Gears project and also a Mount McKinley climb by Mario and his apprentices, we imagined that one of the hits of our program would be to add a requirement that all third-year students organize a major expedition. But we hadn’t realized to what extent our over-achiever clientele would go to push their wild projects to the edge of acceptable adventure; I don’t know why we didn’t grasp that they were just like we were at their age. All of a sudden, Mario and I were overseeing cross-Canada or Baja California kayak expeditions, a ski journey traversing Ellesmere Island, climbs to the summits of Mounts Denali and Logan, treks around the Himalayas, paddles on whitewater rivers in the Arctic and remote Ecuador, cycling tours from Canada to Patagonia, a month-long survival experiment, and therapeutic adventure expeditions with youths faced with cancer, to name just a few. This forced me to write up quite extensive risk-management procedures that were eventually published conjointly by the Quebec Camping Association and Adventure Ecotourism Quebec. All of which took time. I felt like I was a prisoner chained to my desk, allowed but a brief fitness break daily while I watched everyone else roam free.

The university’s knot board. The record is 5 minutes, 38 seconds.

As countless students returned from expeditions to relate events with eyes bright as brand new coins shining in the sun, I identified the common denominator defining adventure — pure and powerful emotions. Nature has a way of intensifying things. Whether flabbergasted by an exciting discovery, scared to death that an ice bridge would collapse, happily overcoming a seemingly impossible obstacle, tenderly facing lost friendships at the end of a trip, being awestruck by amazing scenery, spitting anger at the injustice of spoiling a wild river with a dam or garbage, witnessing cruel inter-animal attacks, or suffering nauseating cramps and agonizing blisters, the emotions in the wilds are so heartfelt they make tears flow. They prove you’re alive.

I longed once again for those expedition-borne emotions. Breaking my spine by ramming into the boards during a hockey game didn’t help. For months I had to wear an awful corset that made me aware for the first time that I was a mere mortal. Although I fully recovered from the bad luck, it fattened me by five kilos. And as a chef, my adoration of rich foods prevented me from ever again enjoying a six-pack silhouette. At least the accident had provided a new sensation.

Someone once stated that you know you’re getting old when you’d rather talk about the things you’ve done instead of the things you’re going to do next. When is the last time you did something for the first time? It seems to me that adventure-type emotions only occur when we opt for a touch of newness.

One project I had had in mind for a while was constructing my own birchbark canoe. It took over two weeks to chase down materials in the forest. Then I forged the crooked knife and the awls I would need and built a traditional shave bench, for I wouldn’t allow myself to cheat by using modern tools. I also found a froe, a tool used for splitting board, for which I made a handle, and cut a metal barrel in half as a soaking/boiling tub. After splitting and whittling cedar ribs, planks, and gunnels until I was buried in shavings, I built a wooden platform in my barn on which to build the canoe. (Years earlier I had purchased an 1853 schoolhouse with a barn and had renovated the first into a unique small home while the second served as a spacious workshop.) I sat many hours sewing with tamarack roots, then installing the planks and steam bending the ribs to force them into place. I also hand sewed an Egyptian cotton sail, because I wanted a sailing rig like the one I had seen in Adney and Chapelle’s reference book.

After a total of nine hundred hours of toil the canoe was ready. I portaged it to the Saguenay River and must admit to tears of emotion as I christened it and paddled away. After a few exhibitions, I legged it the museum of the Centre d’Interpretation de la Métabetchouan, where it still sits proudly.

Sewing a birchbark canoe.

Surely one of the most intense sensations of my life occurred after I had just obtained my airplane pilot’s licence. Ecstatic is a small word to describe my sentiment during that first solo flight, especially when illegally popping targets of miniature cloud puffs at ten thousand feet. The hysteric joy made me yell like a madman. But flying an airplane also resulted in the three downright scariest moments of my life. During my first flight from Quebec to Ontario I was soaring way up there, admiring the spectacular view of the Thousand Islands. The visibility was infinite; a gorgeous day. I synchronized the weather channel, to respect procedure. It said that Toronto was presently enclosed in a storm system with less than thousand-foot ceilings. Like a lost person not believing his compass, I dismissed the weather warning as an old recording. But an hour later I saw it. A black wall. In all my years as an outdoorsman, I had never realized that weather changes were cut so square. I marvelled at this awesome back seat-view of nature for a bit. But then I wondered what to do. Too inexperienced to calculate an alternate landing spot on the fly, I just pushed on, drawn forward by the anticipation of arrival and the complicated ground-transport logistics of a detour.

While pilot training in Chicoutimi, the multitude of uniquely shaped lakes had become easy orienteering reference points. But as I flew into what seemed to be the eye of a hurricane just outside Toronto, the infinite criss-cross of roads prevented me from getting my bearings. I was in way over my head. The turbulence repeatedly seemed to yank the jerking airplane out from under me. With sweaty palms I held on like a granny on a too-wild amusement ride, blindly following my bearing toward Buttonville airport.

Even with the help of the control tower, I couldn’t distinguish the landing strip from the thousands of streets below. I flew through the downpour and right over the airport. After two loops and the tower’s patient guidance, I finally spotted the runway. However, during flight training I had never landed in over seven knots of crosswinds. And now, in the middle of this mess, they were gusting at thirty-five. I landed with a ten-metre bounce, pitching and wavering so badly the right wing just barely missed the ground. Dad had come to pick me up and met me at the gate, wondering why I was jumping in his arms with such fervour, white as a ghost.

On another occasion I landed on a too-short private airstrip in Huntsville. I had no way of knowing the runway was slick with ice, and slid right off the end and up a hill until I ran into a rope fence that wrapped around the propeller. Thankfully there was no damage, and so once again I got off with a good scare — hopefully the last. But the very next day as I was flying out of that hole, the melting ice slowed my takeoff and I barely made it up over the trees; I swear I heard the wheels scratched by branches. To make matters worse, when I got to Ottawa the fog had not lifted as per the weather report, and I resorted to flying just above the river valley underneath a ceiling of but a few hundred feet. I asked Ottawa’s tower for help, and they suggested I switch my destination to Rockcliffe Airport on river right to avoid flying so low over the city. Then they warned me about the high bridges. What high bridges? Yikes! THOSE high bridges. I could barely squeeze in the narrow passage between the trucks and the clouds. There was Parliament Hill, at eye level to my right. I was sure glad to see that runway. Stress caused me to land way too fast; it wasn’t a pretty sight. I parked the aircraft, swore every nasty word I knew, and hopped on a bus for a nine-hour ride back to Chicoutimi.

It turns out I had delayed the landing of a few 737 jets at the Ottawa’s Macdonald-Cartier International Airport and was summoned to file a report to the Ministry of Transports to explain why I was flying in those nasty conditions. The next day I paid two pilots to go fetch the rental plane. Although I obtained pardon from the Ministry, I did give up flying, preferring to stay alive. Whew!

I thought I had felt every emotion. But no. At forty-three years old, I stormed into the university staff room to pick up my mail and stopped dead in my tracks. There she was, of rare beauty, glowing while cutting little blocks of cheese. “What are you doing with that cheese?” I asked.

She gazed at me with mysterious eyes, smiling. “Want a piece?” I liked that evasive answer, so I popped one in my mouth.

“Yech!” I exclaimed without thinking.

“Oh, it’s non-fat cheese I pass around during my conference on nutrition. It’s a substitute when you want to lose weight.”

By then my head was spinning, I was at a loss for words. So I exaggeratingly stuck my stomach way out and blurted: “Well look at me, I’m way too fat. Maybe I should come and listen to your talk!”

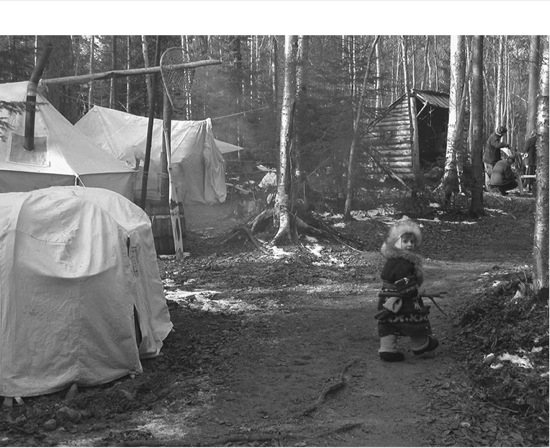

Those must have been the words Lizon wanted to hear, because three years later, Véronica was born. As every parent knows, nothing in the world can compare to the ecstasy of watching this true love grow. Her first canoe trip at two weeks. Her first winter camping trip at three months. Her first fish at a year and a half. I was in heaven. From two years old onward, she loved dressing up to participate in the annual traditional activities colloquium I organized with my students. Probably because she was the hit of the “village.” The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. Fortunately, my lady partner’s serenity counter-balanced my extravagance.

As Véronica grew taller, I decided to build our family a wider nest. The massive barn window offered a spectacular view of the Saguenay River and the Valin Mountains beyond. The tiny farmhouse window offered a spectacular view of the barn wall. That was about to change. I would retire in a home with a lovely panorama. And with soul, I hoped. But building-related choices are not easy with an environmentally conscious mind. Especially an extravagant one.

It took seven years. I cut trees by thinning them here and there on my land. Had them sawn with a portable mill into lumber. Tore down the barn and kept all the best beams and greyed-out planks to recycle them into the new house’s decor. Piled up house parts purchased at auctions and second-hand places. Found a plan on the net and modified it myself. Hired a construction coach and a couple of neighbours. Put on the carpenter’s apron.

I long considered alternative options, like geodesic domes, straw-bale houses and such, but chickened out. Also built the house too big, probably, and with too many windows for proper heat retention. But it’s nice. The central masonry contra-flow heater uses less firewood, which compensates. And its enclosed bake oven heats for free. Every corner of the house holds a memory. Like the baking counter built from the wood of the tree whose bark I used to build the canoe. Or Véronica’s rocking horse. Or the ten-metre-long beam holding up the vaulted ceiling. This most extravagant of survival shelters emits feelings of pride. As for the old schoolhouse, moving it to a new location down the road preserved the heritage.

Véronica in the traditional village.

From the living room rocking chair retirement age appeared on the horizon. Maybe it was time to activate my sailing dream and relax. After purchasing a Siren 17 pocket cruiser, lugging it back from Ontario in February, and spending winter fixing it up, I was ready for my first sail. The shop had totally overhauled the motor at an exorbitant price, so I felt confident in this backup option. Tadoussac’s music festival was a good occasion to take excited Véronica with me for a sleepover at the town’s marina; that way we would avoid the overcrowded main parking lots and try out our boat at the same time.

Tadoussac marina’s boat ramp can only be used at high tide. Oops. Not wanting to wait four hours, we decided to take the car ferry across the mouth of the Saguenay River, admiring the majestic St. Lawrence River, gateway to the sea, and launched the boat from the cement ramp there. Then we motored back across the calm waters, and I managed to dock the sailboat into the marina slip with just one smash. After lunch the winds rose, and we went out into the bay for a first ever attempt at sailing. I prudently hoisted the main sail only, double-reefed, and all went well, except for a couple of unexpected jibes of course. Satisfied, we docked again and walked to town to enjoy the festival’s invigorating music. At the end we were pleased to leave the crowd and return with anticipation to our miniature floating cabin.

The next day brought blustery winds and it was obvious we could not cross the channel back to the van. I chatted with old captains who advised that the traverse would not be possible until late afternoon. So we waited. And waited. Finally the locals confirmed it safe enough, although the waves were a bit tall to my liking. I wouldn’t sail, just motor across. We donned our life vests and safety harnesses and soon Véronica was really enjoying the wild roller-coaster ride. I wasn’t. But we were already two-thirds of the way across, only a few minutes from the cliffs on the opposite shore. That’s when the motor quit. No panic yet. I hoisted the main sail and got back under way. But two minutes later the wind completely died, leaving us bobbing like a cork on crazy leftover waves. The cliffs were too close for comfort, so I pulled out the paddle and soon was sweating profusely, to Véronica’s shouts of encouragement. Brave girl! Turns out one of the captains had been watching all this through binoculars and had advised the coast guard to come to our rescue. I hadn’t even had the presence of mind to call them myself! Parenthood sure magnifies sentiments.

I reflected on my journey thus far and the gamut of emotions it had provided. In the wilderness, from excitement and wonder to worry and fright. At home, from utter joy when my daughter dives into my arms to the excruciating sadness when my best friend Dad disappeared. All part of nature in the larger sense. But there was one emotion I had not yet experienced.

“Welcome to our music school. What can I help you with?”

“Hi, I’d like to sign up for a singing course.”

“Okay. What kind of singing?”

“You know, the kind where you use your voice.”

“Ha, ha, very funny. I mean would you like to try popular singing or classical singing.”

“Huh, popular singing I suppose. But what’s the difference?”

“Well, popular singing is more fun, but if you really want to learn to control your voice you should go for classical. Many of the top popular singers have a classical singing background.”

“Who’s the teacher? Is he good?”

“Réal Toupin. He directs the symphonic orchestra choir. We’re lucky to have him; he comes up from Quebec just once a week to help us out. He’s toured all over the place. Unbelievable singer.”

“Sign me up!”

“Would you like theory too? It’s free. Do you have any experience in music?”

“I’m mostly self-taught, but I’ve taken a few guitar lessons. I’ve been playing for thirty years and I’ve sung in bars a bit, but mostly around campfires. Sure, I’ll go for theory too.”

That’s me alright. Always choosing the hard way. I went there just to improve my voice a little, and now I was signed up for the whole package. And knowing me I wouldn’t quit until I succeeded.

Music has haunted me all my life. That’s one thing I had no talent in. Whereas my teenage pals would pick up an instrument and play after a couple of months, I still couldn’t tune my guitar after five years. And twenty years later, when I purchased a keyboard with included rhythmic patterns, it became obvious that I couldn’t keep a beat either. No wonder no one wanted to jam with me!

But I wanted to play so badly that I kept time by watching the little blue light flash on the machine’s dash until I felt the associated beat in my body. It took months, years even, but music finally penetrated my thick skull. I deserved a medal for tenacity. I’d even been writing songs, and would like to record them for my friends and family. But first I’d take a few singing lessons, just to make sure my voice was okay.

Wednesday night at seven on the dot, a student walked out the studio door and it was my turn to meet the famous Réal Toupin. His bright piercing eyes and huge smile welcome me as I shake his hand. Not five seconds elapse before we’re working.

“Sing with me. DO. Do mi sol do sol mi do. RE. Re fa la re la fa re. MI. Mi sol si mi si sol mi. FA. Fa la do fa do la fa. SOL. Sol si re sol re si sol.”

On the last re I cracked. He informed me that I’m a tenor. To sing higher, I would have to raise the roof of my mouth to expand the cavity, as when yawning. He made me yawn ten times.

“Okay, again. DO. Do mi sol do sol mi do. That’s better. Keep going.”

We vocalized like this for a whole hour, non-stop. This guy had so much passion it was unreal. By the end of the course I’d managed to emit my first fa.

Week after week, I religiously returned to my singing class. It’s like Latin. Discipline, and lots of it. But Réal was so darn intense he made it fun. After five months, I managed a G note. Now for the A flat. There’s a passage between G and A flat apparently. Makes it a money note. Which means you can earn more money when you can sing it.

We started practising my first song. It was a French classic, “Je t’ai donné mon Coeur,” which means “I gave you my heart.” More poetic in French somehow. Réal had chosen it for me because it ended on a sustained A flat. My first attempt was disastrous. Not only could I not reach the high note, I couldn’t vibe the triplet rhythm. This motivated me to practise more at home, or in the wilderness when I wanted to chase the bears away. Another three months and I could finally sing the song, albeit with difficulty.

“Maybe you should try singing it at the end-of-year show?”

“Sure, no problem.”

I hadn’t noticed the word try in his sentence. Bad mistake.

It was the end of April. I’m standing under my umbrella in the woodlot outside the Mont-Jacob concert hall, vocalizing. Beyond hearing distance, I see limousines drive up. Tie-clad men and chic well-dressed ladies enter the theatre. Lots of them. Better go inside and get ready. I passed by the poster announcing the event, the same one that was in the weekend paper. Inside, the decorum looked as it should if the queen was in town.

Backstage I recognized many of Réal’s long-time students I met at a master’s class he had organized, where he had invited his own teacher, diva Jacqueline Martel-Cistellini. Every single one was wearing a fancy tuxedo or a long gown. Except me, in white shirt and suspenders. Réal informed me that I would be going first. What?

I started getting nervous. I fled outside for a minute and vocalized a bit. Stress. I went back to find comfort in my teacher, but he was too busy coaching his stars. Some of the others were peeking out at the crowd between a crack in the curtains. I dared not.

The master of ceremonies was greeted by the crowd with thunderous applause, which doubled in intensity when he presented the professional musician who sat at the grand piano. As he presented my name, I wondered if the audience associated it with the survival-expert me. I got a tap on the back from my coach — or was that a shove? I walked out on stage and heard stifled laughter. Then, all of a sudden, it was quiet, oh so deadly quiet. My throat was dry. Help! I gave a faint smile to the pianist as I took position. There were three hundred pairs of eyes peering straight at my face. More specifically, focused on my lips. I freaked. My legs were literally shaking in my pants; I could not physically control them.

The piano strings vibrated to project the beautiful melody into the audience. There was my chance at fame. Breathe André, try to relax. But I thought I was going to faint instead. My first notes seemed okay. Hey, not bad in fact. After the first verse, I’d gained confidence. I was going to make it through this. My voice was powerful, said Réal. Concentrate, think of yawning. Here comes the A flat. I belched it out. Squawk! The most nauseating, horrible, ugly-duckling squawk anyone has ever heard.

They applauded out of pity. I exited with head hanging in shame. Pure shame. Unadulterated shame. Absolute shame. Ouch!