23

Beginnings and Endings

BY THE NEXT MORNING, the aftershock of our encounter with the Russian soldiers had worn off. We decided to turn our attention toward practicalities. Our first concern was to replace the door that they had kicked down. We didn’t want another band of soldiers, Russian or German, wandering in. So we took a door from a vacant apartment and used it to replace ours.

We also decided we needed to take down the sign that designated our building as an office of the NSDAP (the Nazi Party.) The swastika-laden sign would attract Russians like bees to honey. We removed the sign and threw it into an office upstairs.

We were comforted by the fact that now that the Russians had arrived, the tables had turned on the Nazis. It was they who were now hunted outlaws, and people like ourselves who were “legal.”

As the day progressed, the sounds of battle diminished. Everyone was in a high state of excitement that had been building for the last several days, anticipating the changes that would arrive with the Allies.

The Lebrechts had a radio that we now played constantly. The announcer on the radio was saying, “People of Germany; resist to the last man! Believe in the Führer! We will defeat the demons of the Jewish Bolshevik conspiracy. They shall not succeed! The Führer has seen to it. Relief is on its way. Have faith in the Führer, he will bring about victory.”

We got a good laugh out of that. We were hearing the last gasp of Nazism. No one on the radio talked about where the great Führer was, though. Apparently, he wasn’t going to appear to save the Fatherland in its most desperate hour.

That task was left to the new draftees. In these last days of the war, the Nazis took to conscripting children and the elderly to fight the Russians in the streets. Every available male, from sixteen to sixty, was conscripted into the Volkssturm, the People’s Storm. The younger boys were supplied with Panzerfäust shoulder-fired weapons, designed to pierce the armor of tanks. Elderly men, barely able to walk, were given rifles and whatever other types of weaponry could be found.

Boys as young as twelve were used to operate artillery units. As the Russians approached Berlin, entire battalions made up exclusively of Hitler Youth were outfitted in man-sized uniforms and ordered to defend bridges leading into Berlin. More than 90 percent of these boys were killed or wounded during the ensuing battles, many committing suicide rather than allow themselves to be captured.

Meanwhile, SS troops roamed the streets, looking for deserters. Anyone refusing to fight was shot or hung on the spot. Of course, all this was useless. In his insanity, Hitler would not allow surrender. If the Reich could not defeat the Russians and the Allies, it would go down in a blaze of glory, fighting to the last man—or so Hitler hoped. So strong was Hitler’s control of the German people that Germany did not surrender until May 7, 1945, a week after Hitler finally committed suicide.

We eventually decided it was safe enough to really venture out. All around us, Berlin lay in ruins. The bombings had ceased by mutual agreement of the Allies, to prevent Russian soldiers from being killed. Everywhere we looked, people were wandering the streets, some just curious as we were, others homeless with nowhere to go.

Now most Berliners were in the same position we had been in during most of the war. They became obsessed with doing anything they could to secure food and other articles necessary for survival. The infrastructure that brought supplies to Berlin had been destroyed. In many cases, there was no drinking water, gas, or electricity. Few knew where tomorrow’s meal would come from.

One day, we noticed that many Russian trucks and a few large cranes had arrived and were parked near factory buildings. The Russians literally ripped open factory walls, using the cranes to remove machinery from within the factories and to load them onto trucks. The trucks then took the equipment to railroad cars, in which they were shipped to Russia.

It was brilliant, really. The much-maligned Russians—thought by the Germans to be inept—were dismantling the guts of German industrial might and sending it home for their own use. In doing so, they were giving a boost to their own industrial efforts while simultaneously squashing Germany’s ability to lift itself back up. Without machine tools, Germany’s industries couldn’t function.

The only trouble was that the Russians didn’t have enough railroad cars to move all of the machines, so many were left to sit beside the railroad tracks, rusting. Eventually, many of the machines deteriorated to such an extent that they became unusable, at which point the Russians abandoned them.

A few days after the war ended, the Lebrechts somehow found a larger apartment for the five of us to live in. It was an empty apartment on Ringstrasse 95. The former occupant had been killed by the Russians when they were fighting house to house. He was a fanatical Nazi official who tried to resist the Russian soldiers. The Russians fired on and killed him with their Kalashnikov machine guns. The neighbors of Ringstrasse 95 gave us a detailed account of this when we moved in.

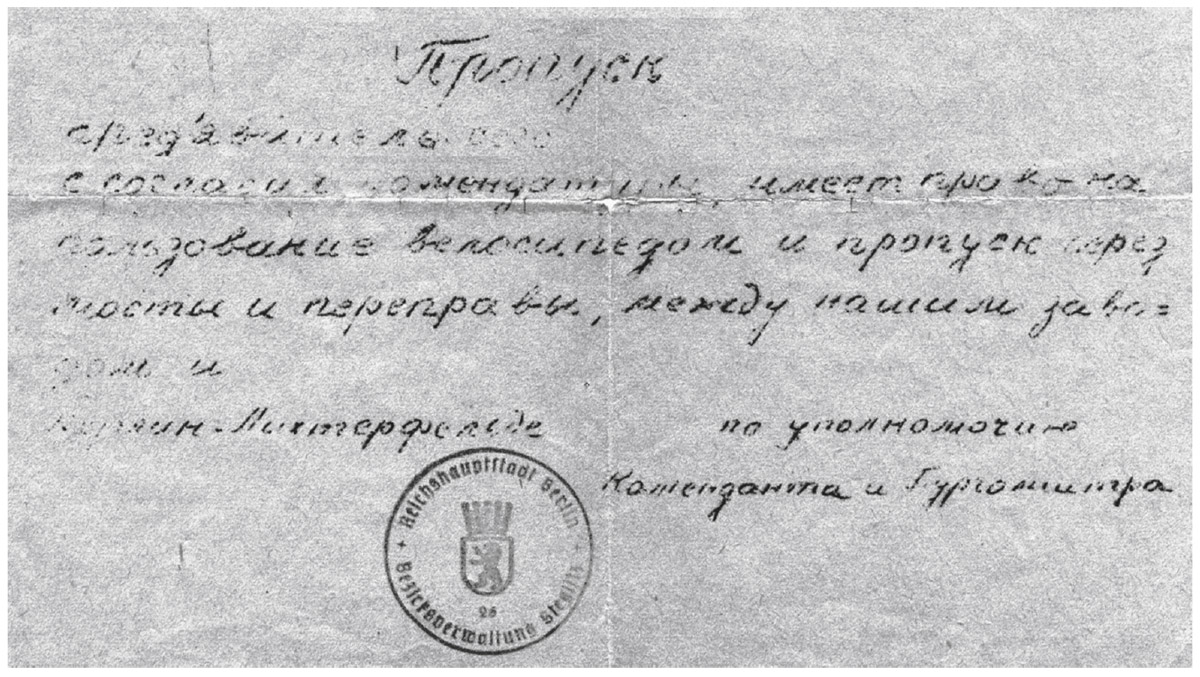

As I ventured out from Ringstrasse 95 each day, I was sure to carry with me the little pass given to me by the Russian soldier that miraculous day at the Lebrechts’. I showed it whenever I was stopped by the Russian soldiers cruising the streets.

In spite of the fact that the war was now over, I still looked over my shoulder constantly for Gestapo. More than two years of constant danger had ingrained in me the need to be on guard wherever I was, day and night. It was now a habit. I felt myself virtually incapable of taking a leisurely public stroll. Fear was still present, even if it needn’t have been.

There were well over one hundred bridges in Berlin. To reach many destinations, one had no choice but to cross water and therefore, to cross a bridge. The Russian soldiers quickly grew fond of standing at the bridge’s exit. They would greet those who had just crossed the bridge by asking them for identification. Generally, the conversation would end when they confiscated the person’s valuables.

I had the pass given me by the Russian soldier and so I had little fear. Each time I was stopped, I would present it and be allowed to move on. One day, after crossing a bridge, the Russian soldier looked at my pass and then looked me up and down. After a moment, he turned around and grabbed a bicycle he had taken from some poor German soul.

He handed it to me, saying, “Get going! Get going!” in Russian, with a smile on his face. I didn’t argue with him. I just jumped on the bike and took off. Two or three days later, another Russian patrol stopped me. The officer spoke German, and once again I gave him my pass.

Travel pass given to me by the Russian Commandant and the mayor of Berlin.

Translation:

CERTIFICATE

For the route to the workplace on the line between Lichterfelde-Ost and Berlin, the bearer of this Certificate, Mr. Dagobert Lewin, Berlin Lichterfelde-Ost, Luisenstr. 1, has to use a bicycle. Because of this, it is requested that he be permitted to pass freely.

Berlin-Lichterfelde, May 25, 1945

By order of the Commandant and the Mayor

“You need to go and exchange this pass for a more official one,” he said. “Go to the police precinct and get one with the proper stamp.”

And so I rode to the command headquarters. It appeared that the Russians had taken over the German civil bureaucracy. The Germans still ran it, but now the Russians supervised. Everything had to be approved by the Russian commandant.

I handed over my pass and told them my address. After a few minutes, they gave me a new pass, with Russian on one side and German on the other. Both confirmed my identity and authorized me to travel in the area by bicycle.

Eventually I decided it was time to leave Berlin. I stayed with the Lebrechts for another week, and then it was time to go.

“But why, Dagobert?” Jenny had asked me, perplexed. “Where are you going? There is no transportation. Berlin is a mess!”

“I need to go see the Kusitzkys in Lübars. I owe it to them. I need to make sure that they are unharmed, and they need to know that I am well. I also needed to tell them about Ilse and Klaus.” I had since learned that after we were captured by the Gestapo, Ilse and Klaus had been deported to Bergen-Belsen.

The Lebrechts understood and wished me well. We made plans to meet at a later date and all promised to stay in touch.

I mounted my bicycle and started making my way to Lübars. The ride was an all-day affair.

I was quite concerned about the Kusitzkys. Would I find them there when I arrived in Lübars? My great fear was that the Gestapo had deported them or otherwise harmed them when it was discovered that they had hidden me. It was well known that anyone who harbored Jews would be imprisoned, sent to the concentration camps, or worse.

I couldn’t forget the look on Anni’s face when the Gestapo arrested us at her house, so serious and sad. I would have a hard time forgiving myself if anything had happened to them.

There was a tremendous amount of destruction along the way to Lübars. Whole neighborhoods had been completely bombed out, and several of the roads I tried to use were impassable. As I made detour after detour, I began to wonder whether I’d be able to get there at all that day. Finally, I reached Lübars. I walked the bike up the steep path and through the garden, leaning it against the house. I knocked at the door, praying that the Kusitzkys were unharmed. After a moment’s wait, the door creaked open.

“Dagobert!” Anni screamed. “Oh my God! It is Dago! Dago!” She hugged me, jumping up and down for joy. Alex came up behind her, staring at me as if he could not believe the evidence of his own eyes. He was a very cool customer, not given to overt displays of emotion. But I could tell from the look on his face that he was genuinely pleased to see me. Maybe even a little more than pleased, but he wouldn’t or couldn’t show it.

In between kisses and hugs, Anni pulled me inside the house and led me to the kitchen table, tears of joy streaming down her cheeks.

“I want to hear about what has happened to you, but first, are you hungry?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, “Like a horse.”

Anni laid out a small feast, which I soon demolished. Then I leaned back, got comfortable, and told them everything that had happened since I had last seen them. It turned out to be a very long story and soon it was past midnight and I could talk no more. Anni took me to a bed, not in the attic but in the second-floor bedroom, the best room in the house. Now I was here as a legitimate guest instead of as a fugitive.

I slept nonstop for twelve hours, awakening only to eat once more. After breakfast, we all sat around the kitchen table and talked. Alex had been told not to go to work that day because of the tremendous food shortages in and around Berlin. Even if there had been meat, there was no transportation to get it from the slaughterhouse to the processing plant. And if there was no meat to be processed, there was no point in Alex going to work.

It was now my turn to ask questions. There was one matter in particular that I had worried over since the day I was arrested at the Kusitzkys’ house. Fearing to know the truth, it took me a second to work up the nerve to ask.

“Anni, what did the Gestapo do to you after I was arrested?”

My palms grew clammy in anticipation of their answer. What if they had been tortured? I couldn’t stand the thought.

Anni looked over at Alex and then back at me.

“Nothing, Dagobert. The Gestapo did nothing to us,” she said.

“Nothing?” I asked in amazement. This was unheard of. The Kusitzkys had committed a grievous crime in the eyes of the Nazi government. They had succored enemies of the state—Jews.

“Nothing,” Anni continued. “They did ask us a few questions, but we just kept repeating that we were amazed to find out that you were Jewish. We said we had no idea. We only thought you were refugees who had been bombed out of your homes. We thought we were helping fellow Germans.”

“And they believed you?” I asked in disbelief.

“Who knows whether they believed us?” Alex said. “It doesn’t matter. What does matter is that they left us alone.”

“It was as though the Lord himself was watching over us,” Anni said. “God protected us.”

I nodded, smiling. But tears began to well up in my eyes. For some reason, Anni’s words had stirred something within me, a flood of memories, thoughts, and feelings that the day-to-day demands of survival had driven from my mind.

For the first time in quite a while, I thought about my parents.

My poor parents! What had happened to them? Was there a chance that they were still alive, attempting to return and find me? I desperately, desperately wanted to believe it. All of my happiness at seeing Jenny, Leo, Horst, and Heinz alive; my joy that Anni and Alex were unharmed; the euphoria brought on by the war’s imminent ending—all of this was tempered by my fear for my parents.

I fell asleep that night with my mind vacillating between jubilation at the fact that this hideous war had finally ended and despair at the probable fate of my mother and father. I had no way of knowing what had happened to my parents. From their postcard, I believed that they had been sent to a concentration camp in Trawniki, Poland. It would be a miracle if they had survived the war.

But then, I was no stranger to miracles. In my own case, the odds of surviving had been overwhelmingly against me. On three separate occasions, I should have died.

What were the odds that a Russian soldier would have read a textbook written by an uncle I could barely recall? And that this same soldier would happen to be the one to lead an assault on the building I was living in? That this soldier, poised on the verge of spraying the room with machine-gun fire, trembling with the tension of battle, would hesitate to shoot, deciding to question us instead? And that this soldier would, by chance, be Jewish and speak the Yiddish language, thereby allowing us to communicate?

It was beyond my ability to calculate, but I knew the odds must be astronomical.

What were the odds that I would encounter my friend Heinrich on my way to work at the gun factory? That Heinrich would risk severe punishment to tell me that all Jewish workers were being deported? That he would give me a lead that would help me find a place to hide? Had I missed him, I would have been deported along with all the other workers to a concentration camp where I almost certainly would have died.

And what were the odds that, once I was finally arrested, I would find myself in a situation that allowed me to make a key to a locked gate, enabling me to escape? What were the odds that I would meet the people and obtain the materials that resulted in my current freedom?

In each of these instances, something that could certainly be called a miracle had saved me.

Three miracles for three death sentences.

It would take a man far wiser than I to understand why I lived when so many others died. Was it fate, destiny, mere chance, or the Hand of God? Whatever the reason, if there was any reason at all, these three miracles saved me from the fate of millions of my fellow Jews. And for that, at least, I will be eternally grateful.