7

Marriage

SHAKING ONLY A LITTLE, I said, “I do.”

This was in answer to a question I never expected to hear at the tender age of nineteen. It was something along the classical lines of “Do you, Dagobert Lewin, take Ilse Perl as your lawful wedded wife?”

The events that led up to my answer had begun only a few short weeks ago. After moving into Schlesinger’s apartment, my life, at home and at work, gradually assumed as much of a state of monotony as was possible for one expecting disaster every minute. I came home each evening, exhausted. I would be greeted by the resident couple, who would hand me a note with household chores to do and then retreat back into their bedroom. I would eat what food I had available and proceed to do whatever it was that needed doing, usually some sort of repair.

After a week or so, the requests slowed down. There wasn’t much more to fix. The apartment probably hadn’t run so smoothly in years.

One evening, after I returned from work, the door to the apartment creaked open. Aha, I thought to myself. I know what will be next on my repair request list—oiling the door hinges. I decided to go ahead and take care of it before they asked and started walking toward the cabinet where I thought I’d find the proper oil.

As I approached the cabinet, I heard footsteps shuffling through the door. The footsteps were distinctive. They were Ilse’s.

She stood before me, as beautiful as when I had first met her. Milky white skin, shiny auburn hair, looking radiant. Once again, she wore her white nurse’s uniform.

“Ilse,” I exclaimed, unable to hide my delight at her presence. “Hello!”

“Dagobert?” The look on her face told me that she had come here to grieve, expecting to find an apartment occupied only by memories of her beloved aunt. My presence here suddenly seemed invasive, almost sacrilegious, as if I had intruded on a very private moment. It made the next few minutes that much more difficult.

“Uh, I guess you were not told that I was living here,” I began, trying to explain my presence there.

She continued to stare at me, surprise written large on her face.

“Let me explain,” I said, desperately trying to head off the explosion that I felt sure must be imminent. “Two weeks ago, the Gestapo confiscated my parent’s apartment. There was a note on my door telling me to be out by the next morning. I didn’t know where to go, and I thought of your aunt Selma. I had visited her a few times since I met you here, and she was always very kind to me. I hoped she might let me stay here for a while, until I could find another place.”

Ilse continued to stare dead straight at me.

“So the next morning I packed my suitcase and came here. The couple who were living with your aunt invited me in. Once I got here, they told me the terrible news, that your aunt had been arrested. Of course, I was horrified. But then, they asked me if I could stay here with them. They needed help with the rent, and they also needed someone who could take care of the place, make repairs and the like.”

There was silence for a few seconds and then Ilse spoke. “So you’re living here, Dagobert?”

Somehow, her question made me feel guilty, as though I was being accused of a crime. I tried to respond casually, but I couldn’t help feeling as though I had done something wrong. “Well, yes. I guess you could say that.”

“I see,” she said seriously. “So this couple invited you to live here?”

“Umm, yes, they did,” I said, waiting for the fireworks to start.

There was silence again. Ilse seemed to be pondering the situation. Finally she spoke again. “Interesting.”

And that was all she said. She walked over to the sofa, rubbed her hand over it as though she were inspecting it for damage and sat down, a thoughtful expression on her face. I didn’t know what to do, so I walked over and sat in a chair across from her, awaiting the verdict.

Finally she said, “Well, I guess it’s fine. I suppose it’s for the best.”

Upon hearing this, I nearly jumped for joy. I had been afraid that she would ask me to leave, and I had nowhere else to go.

Ilse continued, “It is sweet of them to think that my aunties will be coming back. Yes. It’s a sweet thought.”

I nodded in agreement, feeling a bit foolish. I thought I had best make some conversation, lest she think the situation over and change her mind. “And you, Ilse? How are you? I am so terribly sorry about your aunt Selma. So very sorry. I know what it is like to have someone you love taken away from you.”

Ilse looked at me up and down. She rose and said, “Yes, Dagobert, I guess you do. It is terribly hard, really, isn’t it? To have them gone. Poof. Almost as though they never existed.” She paused again and looked at me. “Actually, Dagobert, I am glad you are able to stay here. My aunties would also be happy, I think.”

I was relieved that Ilse felt this way. I dreaded her disapproval, which would have meant my immediate departure.

“And you, Ilse? How are things at the hospital?”

“They are fine, thank you. Tensions are mounting all the time. It is very worrisome. But at least I still have a job, and Klaus is still safe.”

Klaus. The mention of her son brought back the memories of our last conversation.

“Where is Klaus staying now?” I asked. “Is he with you at the hospital?”

“Oh no,” she responded. “I live in a dorm with the other single nurses. There is no room there for a child; they would not allow it. He is living in a children’s home where he is very well cared for. The women who work there are very fond of him and extremely kind. I am lucky to have them.”

“That’s good.”

“Of course,” she continued, “I don’t know how long we will remain lucky. Since I am a nurse in the hospital, I have some degree of protection, but I doubt it will last forever. I am terrified by the thought that our special status will end.”

We continued to talk for a while. Ilse told me she had come to see her aunts’ apartment and to fetch a few things of sentimental value. It was quite late when we finished talking, and we were both very tired. Ilse said she would sleep in Selma’s old room and then leave in the morning. And so we bid each other good night. I retreated into Minna’s room, where I usually slept.

I had been asleep for a few hours when I became aware that I was not alone. There was someone in the bed with me, someone warm and soft. Through the first foggy minutes of awakening, I recognized Ilse’s form, her body outlined in the moonlight. It was like a dream. I awoke in the early morning, feeling exhausted but satisfied. I turned over in my bed, sheets rumpled, blankets half on the floor.

Ilse was gone. Gone from the bed, gone from the room. I threw on my clothes and went walking through the rest of the apartment. She was nowhere to be found. I was shocked, but I had no choice except to go on with my day. After a quick breakfast, I departed for the gun factory.

The following evening, the door to the apartment swung open to reveal Ilse, along with someone I had heard about but never met. His name was Klaus and he was five years old.

With no mention of the activity of the night before, I walked with Klaus over to the sofa, sat down beside him, and tried to make small talk. He was a very nice-looking little boy, with dark brown hair and sparkling brown eyes. He was obviously quite intelligent.

I talked to him about the children’s home, his friends there, and other matters of great importance. I was pleased with myself for being able to communicate with him at all. I had never held a conversation with anyone so young before. An hour or so later, Ilse announced it was time for them to go home. She smiled at me as she took Klaus’s hand and led him out the door.

I just stood there, confused. Ilse had said nothing about last night. Not having any other choice, I spent the next days as normally as I could, thinking often of Ilse. I could not help but wonder about her reasons for acting the way she had. I had a feeling that there was more to this than met the eye. She had never impressed me as being the impulsive type, and her behavior baffled me.

Later, I would discover some of the implications of our night together. For now, I was content to experience the changes that she had initiated. I felt like a different person, as if I had matured overnight and had somehow crossed through a mysterious barrier, to emerge on the other side as an adult.

On June 30, 1942, on my way to the gun factory, I passed a newsstand and noticed a headline: JEWISH SCHOOLS CLOSED FOR GOOD! I stopped abruptly and stared at the headline. I felt my stomach turn over. If there had ever been any doubt in my mind that the Nazis sought the destruction of Germany’s Jews, it was now gone forever. What was happening to the Jews was unbelievable. What else could they do? They had arrested and deported most of us already, and now they were forbidding those who remained any education whatsoever.

Education has always played a major part in the survival of Jews everywhere. Education was the means by which Jews, as well as other peoples, could rise above a subsistence level existence to obtain security for family and self. Education and study were urged on every Jewish child as the most worthwhile activity they could undertake. It was almost holy. The closing of our schools was a message from the German government: they were telling us that this was the beginning of the end.

It was therefore not surprising that this was the chief topic of conversation during lunchtime in the gun factory. This latest attack on our civil rights did not bode well for our future. “They want to get rid of all of us,” said one of the men who worked on my floor. “They’re going to take everyone. No one is safe.” Anxiety levels ran extremely high. Everyone was so tense that it was hard to concentrate on our work. We were all living with a constant outpouring of adrenaline, wondering who would be the next to go. It was enough to send anyone over the edge.

One measure of how seriously the Jewish community took this news was reflected in the suicide rate. After the news became common knowledge, there was a radical increase in the number of suicides among Berlin’s remaining Jews, especially those who had already been arrested and were awaiting deportation.

Ilse had told me that the Jewish Hospital was being flooded with attempted suicides. She said it had become a depressing place to work because of it. Doctors and nurses debated endlessly whether they should save these people, or whether it was more humane to let them die. If the doctors had possessed crystal balls with which to view their futures, the debates would have been short and sweet.

There are no words to describe the daily horror life in Berlin had become. Some of those intending suicide took overdoses of Veronal, a sleeping pill. Poisons were traded at extremely high prices on the black market. Sometimes they worked, and sometimes they didn’t. Other poor souls threw themselves over the balcony at the Levetzowstrasse synagogue, where my parents and I had been taken. They preferred to fall to their deaths rather than wait to be deported.

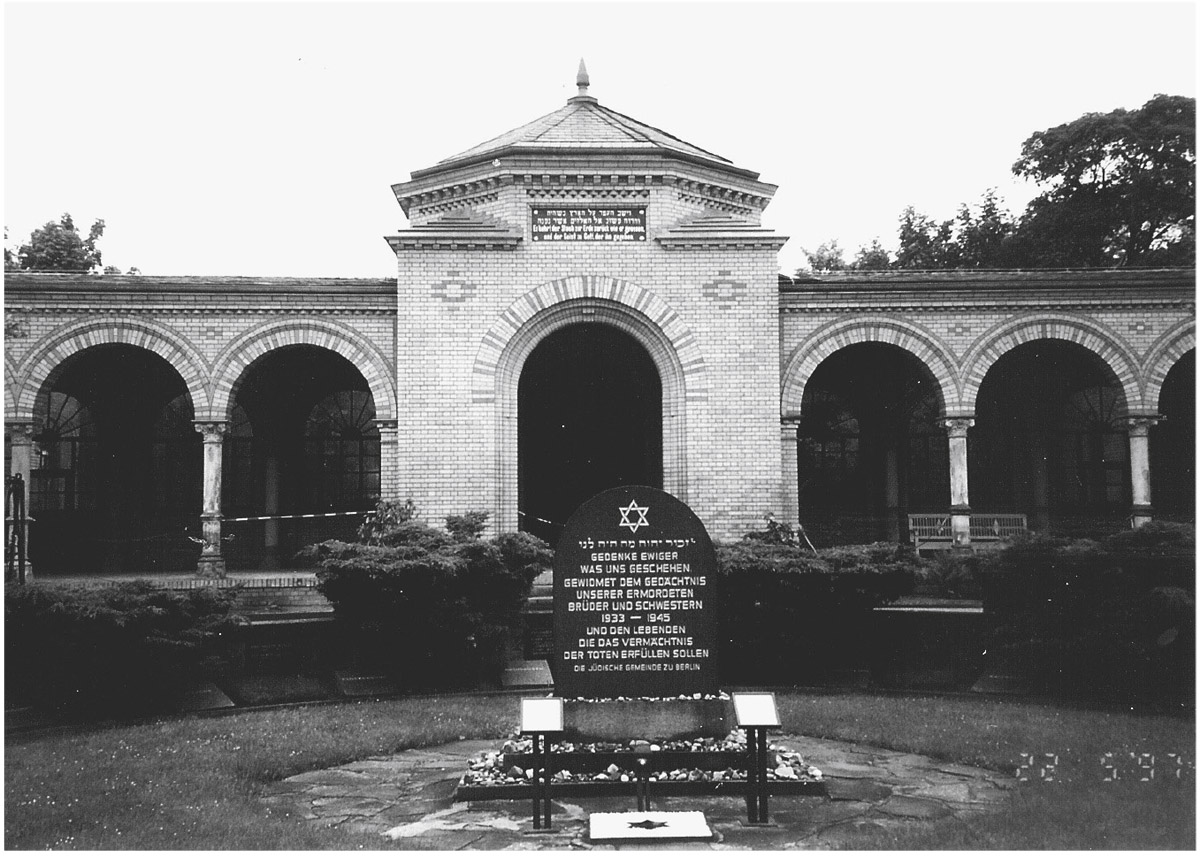

Entrance to Weissensee cemetery, where the majority of Jewish suicides were buried. The inscription on the memorial plaque reads: REMEMBER ETERNALLY WHAT HAPPENED TO US. DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF OUR MURDERED BROTHERS AND SISTERS. 1933–1945 AND THE LIVING WHO HAVE TO FULFILL THE LEGACY OF THE DEAD.

Over the next few months, Ilse would occasionally come to see me at her aunts’ apartment. She was becoming more and more concerned about her and Klaus’s safety. She and the other nurses could be arrested at any time. It was hard to know what to do and, in any case, our options were limited.

Then, one day in the fall of 1942, I received a letter at Frau Schlesinger’s apartment. It was from Ilse. This is peculiar, I thought to myself. We usually communicated in person. I wondered why she would be sending me a letter. I went into my room and sat on the bed, quickly running my finger under the envelope’s crease to open it. It was only one page. I took it out and read:

“Dagobert,” she wrote, “I have contracted typhus from a patient and am now in the hospital myself. I will probably be here for a long time. Please come and see me when you can.”

Typhus. How horrible, I thought to myself. She must be very sick. Typhus was an extremely contagious, lice-borne disease. It typically appeared in areas devastated by war or famine. The mortality rate ran as high as 20 percent, and death from it was excruciatingly painful.

A few days later, I awoke, got dressed, and went straight to the hospital. Before being allowed to see her, I was made to put on a hospital coat and mask. Ilse looked very sick, very weak. But upon seeing me, her face brightened a bit and she managed to hold a short conversation. “Dagobert, I am terrified! I think that, as soon as I am well, I might be deported. There is talk that they are going to arrest all of the single nurses at the hospital. It is so awful!”

I tried to reassure her. “Just rest,” I told her. “You need your strength to get well.”

Soon after that, the nurse told me I had to leave and allow Ilse to sleep. “I’ll be back next week if I can,” I told her.

And so, after another week at the gun factory, I returned to see Ilse. I came back a few times after that. Each visit was very short. Each conversation covered the same subject: fear. Fear that she would soon be deported.

A couple months later, Ilse was feeling much better physically but remained too weak to be released. As her release date approached, she continued to go downhill emotionally. She was terrified, but there was nothing to be done.

“Dagobert,” Ilse said, “this is very serious. Single nurses with children are going to be scheduled for deportation. Children without two parents are also being deported. Klaus and I are in great danger.”

I didn’t know what else to say. We had discussed the situation many times and each time I had tried to make her feel better. I told her to concentrate on getting well, but there was little I could do to comfort her. Now the situation was different. She was nearly well. Her fears might well become reality.

“Dagobert,” she continued, “please help me. Please help little Klaus and me.”

I continued to look at her without saying a word.

“Dagobert. Please marry me.”

I gasped.

“Dagobert, it is my only hope. If I am married, I might be able to remain in Berlin. If I am a married nurse, I won’t be scheduled for deportation, at least not immediately.”

Suddenly, I had trouble looking Ilse in the eyes. The end of the bed attracted my attention and I stared at it, speechless.

“You would be saving my life, Dagobert. Saving Klaus’s life.”

I tried to concentrate on breathing. My head was swimming, my thoughts churning frantically, making me dizzy. Marriage? Me? Married? The ringing in my ears began again. I was only able to comprehend about one word in three, as she continued to plead.

“Please, Dagobert? Help Klaus and me.”

Klaus. Mention of that little boy made my heart stir. And all of a sudden, my brain began to work again. You have the opportunity to help her, I told myself. To help Klaus.

I turned back to Ilse and looked at her desperate face. There were tears streaming down her cheeks.

Dagobert, I told myself, this is the right thing to do.

She continued, “Being married might also help you, Dagobert. Who knows what will happen to the Jews working in the factories? Even though you are helping the Nazi war effort, one day they may decide to deport all of you. And they might begin with single people like yourself.”

I thought about this. She could be right. I finally spoke, “So, Ilse, how do you propose we go about this?”

Her eyes brightened. “I know exactly how. I already have it all worked out. The nurse on this floor is a friend of mine. I have asked and she has agreed to let me leave for a few hours to go and get married. Then I would come back here for the rest of the prescribed hospital stay.”

Hmm. She had it all worked out. She had done the research. Obviously, a methodical woman. Ilse continued, “That way, when I am released, I will be married. They will not be able to take me away with the single nurses.”

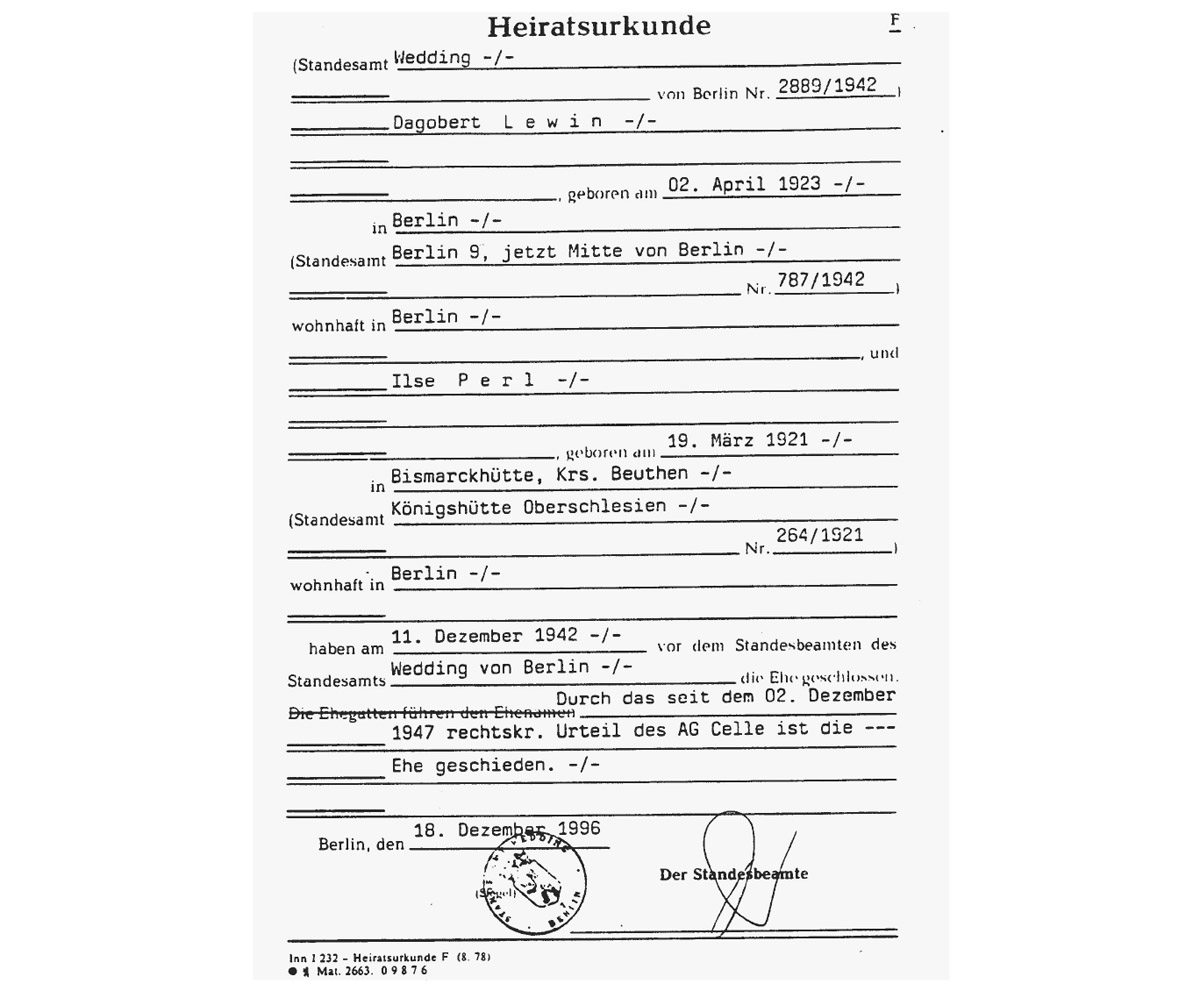

Certificate of my marriage.

The next day, on December 11, 1942, I went to the hospital. I had just been switched to the night shift at the gun factory, so I was able to go during the day. Once there, I helped Ilse get ready, and we left for the Standesamt. This was a registry office that performed weddings, among other public services. There, in a matter of two hours, we waited in line, did the proper paperwork, and went through the wedding ceremony. All very perfunctory, with very little said by either one of us. It was not exactly how I expected my wedding day to be. But then again, nothing in my life was turning out the way I expected.

After the deed was done, we returned to the hospital, where a few of Ilse’s nurse friends greeted us with congratulations. It wasn’t possible to obtain a wedding cake, so we celebrated by consuming a huge bowl of ice cream. I stayed with Ilse in her room into the evening, until it was time to go to work at the gun factory.

While at work, I pondered the monumental event that had taken place that day. Regrettably, there were no monumental feelings to accompany it. I was married. I was a husband, practically a father. But it was all very otherworldly, as if it had happened to someone else. Maybe it wasn’t a marriage made in heaven, but I had done a good deed for a good person and her child. And for that, I was happy.

In the next few days, Ilse was released from the hospital. Now that she was married, she was not allowed to continue living in the single nurses’ dorm at the Jewish Hospital. We would have to find somewhere else to live.

Living together at her aunts’ former apartment was also not an option. A few weeks earlier, the Gentile couple who lived there with me announced that they would be moving back to the wife’s hometown in the countryside. They were fearful of being in Berlin during the war, fearful of food shortages. They were fearful of the bombings that had begun and only threatened to get worse. For these reasons, they abandoned the apartment and left for the country. Since I was a Jew, I would not be able to live in the three-bedroom flat without other Aryans in residence. That was now forbidden.

So the timing of the wedding and subsequent moving in with Ilse turned out to be a godsend for me. Ilse found a room for the three of us at Grabbeallee 27. We rented it from a woman who was a night nurse at the Jewish hospital. She and her husband welcomed the extra money, and she even offered to watch Klaus while Ilse and I were at work during the day.

This was a very exciting prospect for Ilse. She had longed to live with Klaus again, but she had been forced to let him stay at the children’s home because she had no one to care for him during the day.

The next week, Ilse and I went to the children’s home, retrieved Klaus, and moved him into our room at Grabbeallee 27. Ilse and I went to work while Klaus stayed with our female landlord. And somehow, we eked out a decent semblance of a family life.

So things continued, until one day a few weeks later when lightning struck us for the second time. In this case, however, the lightning bolts were not the less painful version generated by thunderclouds. Instead, the dual lightning bolts of the SS, in its Gestapo incarnation, came hammering at my door once again, seeking the destruction of myself and my new family.

On this day, we heard the now-familiar pounding at our door, accompanied by the insistent demand for immediate entrance. The Gestapo once again ordered us to pack our bags for instant departure. We were arrested pending deportation. Our crime, once again, was in being Jewish and thereby impeding the progress of the Reich toward the ultimate goal of becoming Judenrein (cleansed of Jews).

We were taken to Grosse Hamburger Strasse, a collection point for Jews being deported. As we entered the building, we were instructed to get in a line. I thought we were done for and on our way to the boxcars to be taken to the East.

“Papers!” the Gestapo agent standing beside the line barked.

I stood beside Ilse and held her hand tight. She held onto Klaus.

I admit to being overwhelmed with fear. My mind was filled with the memories of one year ago. Like today, a family of three—two parents and a son—walked slowly to the head of a line where their fate would be decided. Tears welled up in my eyes as I remembered it. And then the irony sank in. A year ago in a line much like this one, it had been I who was the young boy walking with his parents. Now I was a parent, walking with another little boy, Klaus.

This was my new family, and though I was only nineteen, I was the head of it. I clung to Ilse and Klaus as we ventured forward. As before, a table stood in front of us with a Gestapo agent sitting behind it. As soon as we got to the head of the line, Ilse produced her schutzkarte, or protection card. This had been given to her by the director of the Jewish Hospital, Dr. Walter Lustig.

Dr. Lustig had a special relationship with the Gestapo. They depended on Lustig to keep the hospital running, and Lustig depended on them to protect his doctors and nurses from deportation. Lustig knew that the Gestapo was rounding up Jews throughout Berlin. He also knew he couldn’t afford to lose his staff. No staff would mean no hospital. So Dr. Lustig arranged with the Gestapo to give certain hospital employees schutzkarten, or protection cards. These cards allowed the employees to purchase ration cards and, in the event of an arrest, would temporarily protect them and their families.

I held my breath. The Gestapo agent glanced hard at Ilse’s schutzkarte and looked all three of us up and down. He grunted, mumbled something I didn’t understand and pointed his finger to the door. Ilse and I looked at each other hopefully. We looked back at the Gestapo agent.

“Raus!” he yelled at us. “Schnell!” I looked again at Ilse, my heart bursting with relief. He was telling us to Get out! Fast! I bent down, picked up Klaus, took Ilse’s hand, and we walked out the door, just as we had been ordered: fast.

Once we got outside into the fresh air, we hugged and held each other close for a moment or two. Thankful. So thankful. For as strange as our marriage had been, prompted by the terrors of Hitler, I had to admit to myself that it was wonderful not to be alone. And I also had to admit that Ilse’s predictions had been correct. Our marriage helped not only her. It had also, at least for now, saved me.

For a brief period of time, we went back to Grabbeallee 27. Back to work. Back to family life.

The level of fear in the hospital’s rumor mill escalated every day. Ilse came home with new stories about how the protection cards would be canceled soon, and how Dr. Lustig was going to have to choose more hospital employees for deportation. Ilse and I talked about our urgent need to make a move. We both felt the same way. We could not afford to tempt fate again. We could not count on being released another time. We had to make plans to go into hiding. Frankly, I doubted my ability to take care of myself, much less an entire family.

But we had no idea how soon we’d need to make that move. In a few weeks’ time, we would have no choice but to run for our lives.